The Definitives

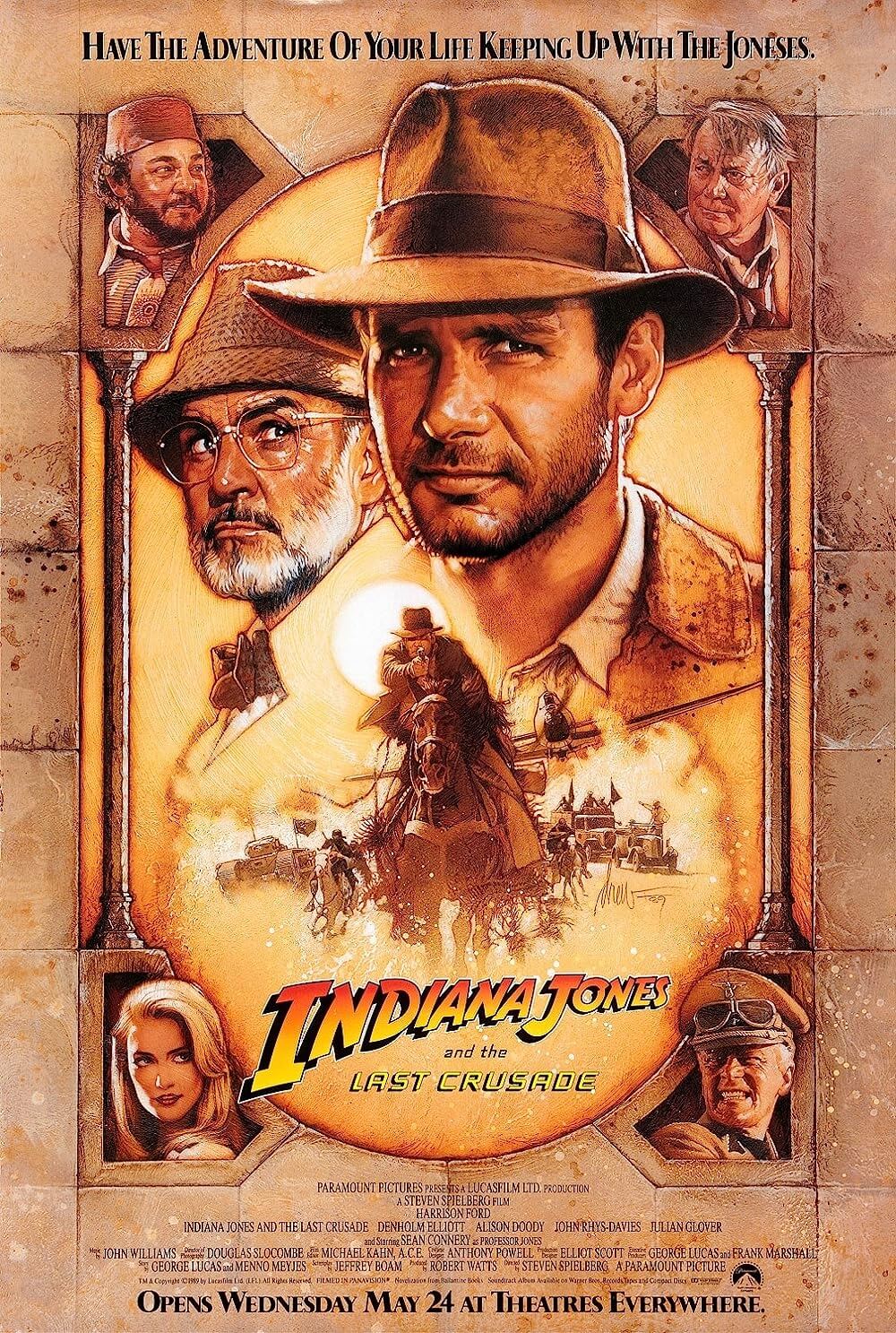

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

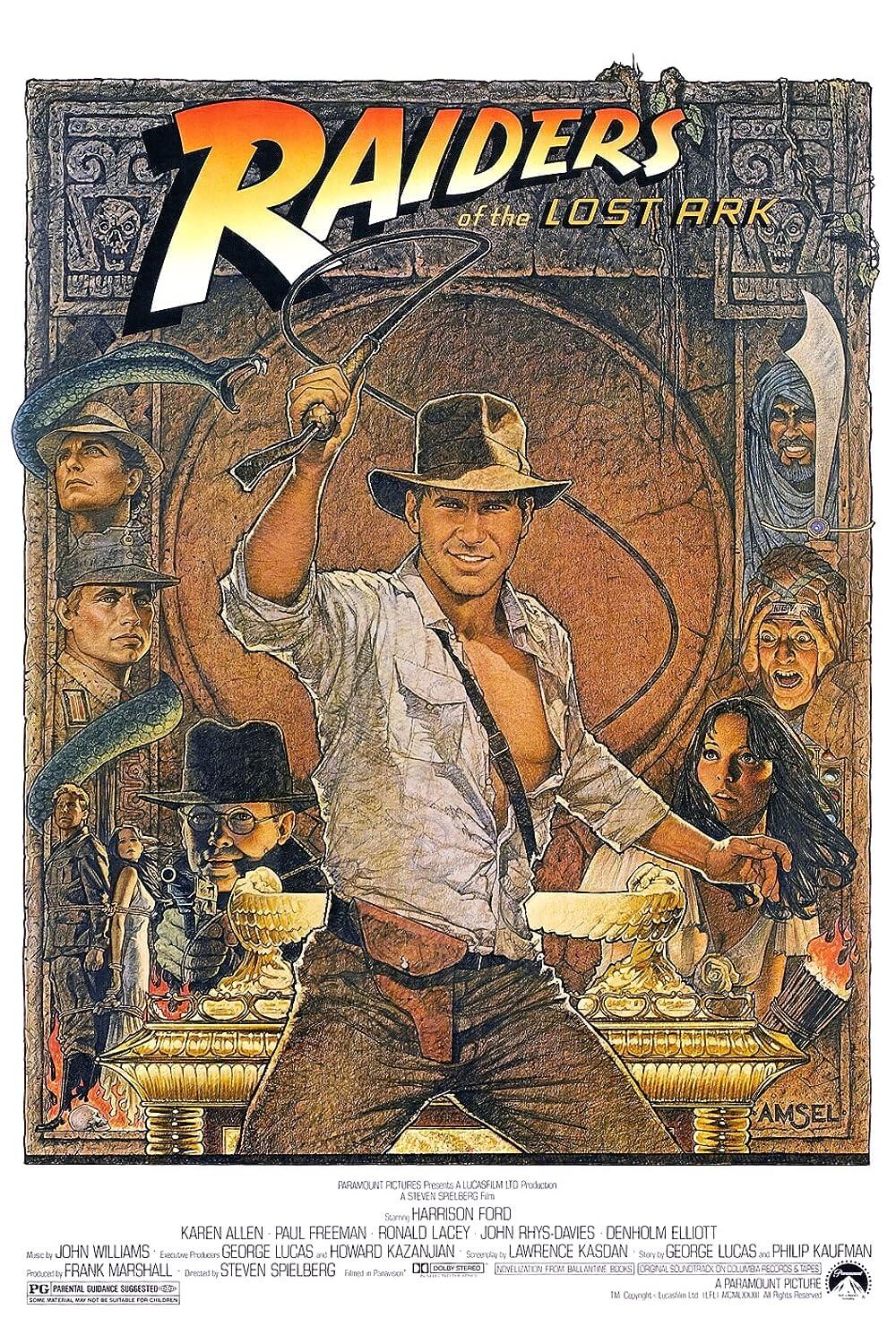

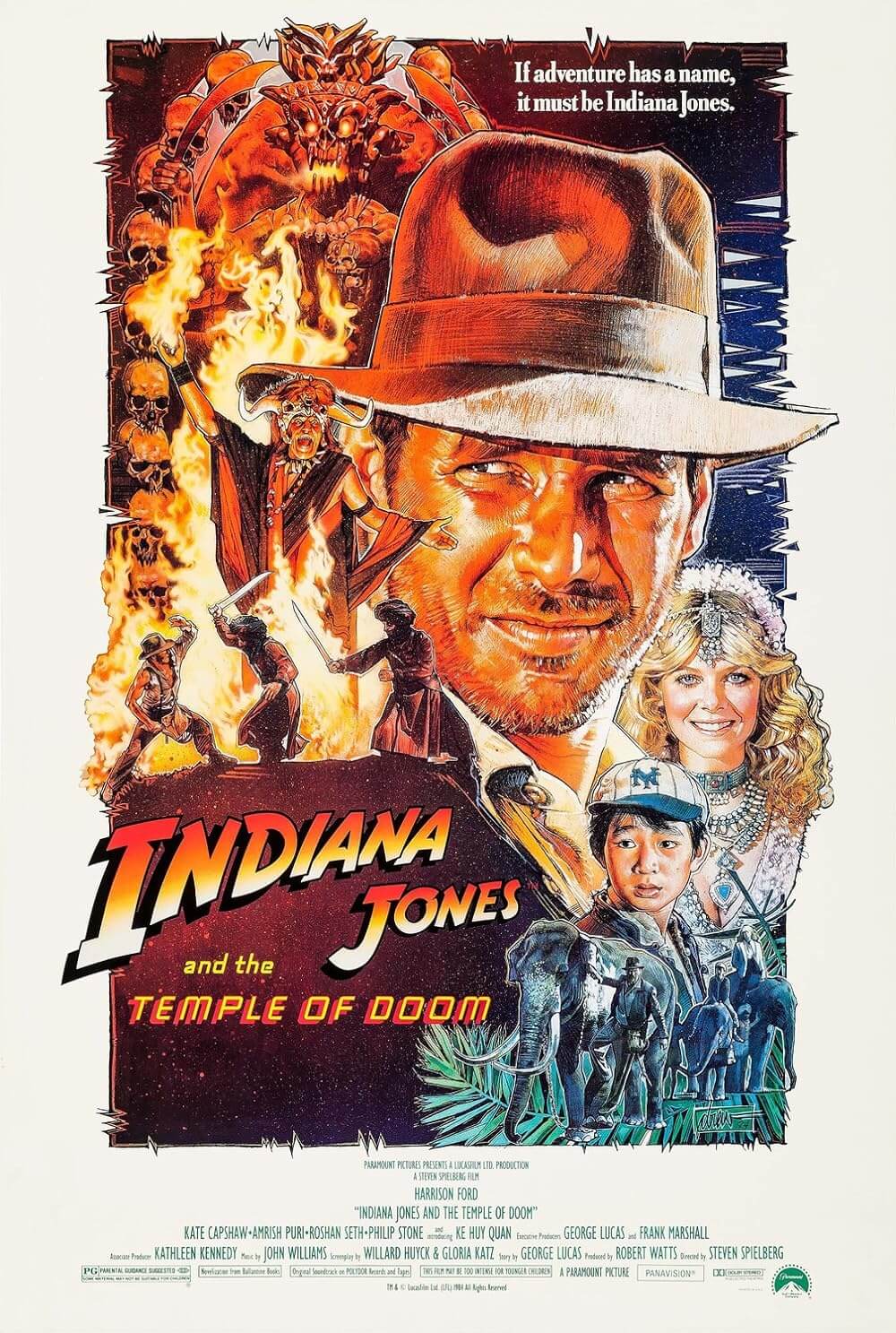

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade deviates from the full-blown Saturday serial adventure formula so jealously adhered to by its predecessors. While keeping our basic escapist moviegoing desires soothed with breathtaking chases and exotic European and West Asian locales, the film’s temperament takes a lighter, emotional detour, above all when compared to (and undoubtedly as a result of) the near horror tone of its immediate predecessor, Temple of Doom. Filled with constant laughs and a surprising poignancy given the inclusion of Indiana Jones’ father, played by Sean Connery, the film’s thrills offer a wieldy entertainment harkening back to the plot schematics of Raiders of the Lost Ark. But to whatever degree the raw suspense of the franchise quiets in this third Indian Jones adventure, the character depth increases tenfold and maintains our involvement on equal planes as the previous entries, yet on alternate dimensions of viewer connectivity.

Influential film critic Pauline Kael famously griped about the characterizations in Raiders of the Lost Ark by claiming they are nonexistent; she (unduly) called the entire production “impersonal.” But Harrison Ford’s archeology professor and treasure-protector is pointedly flawed, occasionally slapdash, and wholly embodied by the actor into a singular persona not requiring deep-rooted emotional or psychological explication. Indiana Jones is fixed in his simplicity, making his presence effortless for the audience in the wake of otherwise complicated special effects, villains, and plots he seeks to uncover in his adventures. Nevertheless, The Last Crusade could easily serve to appease Kael’s criticisms since, more than the film’s MacGuffin of The Holy Grail, this third entry in the Indiana Jones series relies on expounding the emotional history and familial underpinnings of our hero. In true Spielbergian form, the film is complete with a prologue reaching back into Indy’s rebellious teen years, intimating that our hero will always remain a young-at-heart adventurer who never grew up and still has lingering daddy issues, not unlike the director himself.

Following the unwarranted misconception that they somehow failed or perhaps frightened their audience with uncomfortable extremes with Temple of Doom (despite considerable box office earnings, more than double its budget), director Steven Spielberg and producer George Lucas sought a homecoming to their original Raiders of the Lost Ark formula, wherein Indy fights Nazis while in search of a religious artifact. This formula was successful because the pre-established religious and historical iconography inhabiting the narrative was familiar, thus no challenge for moviegoers to consume. Lucas suggested the MacGuffin of The Holy Grail, serving up Indiana Jones as a modern-day knight of Arthurian proportions. What could be more heroic? Spielberg initially rejected the idea because he was reminded of Terry Gilliam’s comedy classic Monty Python and the Holy Grail (not that Gilliam’s knights ever came close to discovering the Grail). Spielberg had long desired an Indiana Jones adventure exploring two elements: a haunted castle and the rambunctious Monkey King from Chinese legend. Chris Columbus, who had written the Spielberg-produced movies Gremlins and The Goonies, was commissioned to write the screenplay; his yarn took place in Africa, used Spielberg’s dream MacGuffin of the Monkey King, and at one point featured Indy on top of a rhinoceros chasing bad guys. Needless to say, they passed on Columbus’ scenario.

Following the unwarranted misconception that they somehow failed or perhaps frightened their audience with uncomfortable extremes with Temple of Doom (despite considerable box office earnings, more than double its budget), director Steven Spielberg and producer George Lucas sought a homecoming to their original Raiders of the Lost Ark formula, wherein Indy fights Nazis while in search of a religious artifact. This formula was successful because the pre-established religious and historical iconography inhabiting the narrative was familiar, thus no challenge for moviegoers to consume. Lucas suggested the MacGuffin of The Holy Grail, serving up Indiana Jones as a modern-day knight of Arthurian proportions. What could be more heroic? Spielberg initially rejected the idea because he was reminded of Terry Gilliam’s comedy classic Monty Python and the Holy Grail (not that Gilliam’s knights ever came close to discovering the Grail). Spielberg had long desired an Indiana Jones adventure exploring two elements: a haunted castle and the rambunctious Monkey King from Chinese legend. Chris Columbus, who had written the Spielberg-produced movies Gremlins and The Goonies, was commissioned to write the screenplay; his yarn took place in Africa, used Spielberg’s dream MacGuffin of the Monkey King, and at one point featured Indy on top of a rhinoceros chasing bad guys. Needless to say, they passed on Columbus’ scenario.

Meanwhile, as Lucas developed his concepts for The Holy Grail device with another writer, Menno Meyjes (screenwriter on Spielberg’s The Color Purple), the producer soon realized that Spielberg wanted more than a MacGuffin to drive his picture. He wanted an emotional growth for a character otherwise entrenched in his singularity—a dangerous concept, changing the nature of a character whose simplicity was already a proven triumph. Aiming for mass appeal once more, the filmmakers agreed to humanize Indiana Jones further by mapping his family life, namely his father, initially envisioned as a cantankerous Walter Brennan figure. Screenwriter Jeffrey Boam (The Dead Zone) was approached next and given only a few criteria: use of The Holy Grail, the inclusion of more humor, and Indy’s father as a humanizing device. Spielberg and Lucas accepted Boam’s script; however, many of the film’s most enjoyable sequences (the tank and motorcycle chases) were added afterward or altogether improvised, while others were added during uncredited rewrites by Tom Stoppard (Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun). The result was another type of Indiana Jones film entirely, albeit reminiscent of Raiders of the Lost Ark, yet on its own as distinctive in pitch—just as each entry had managed thus far.

Each Indiana Jones film begins with an appetizer, the fundamental climax of Indy’s previous untold adventure, leading into the film’s central conflict. The Last Crusade begins with a look at our hero at an early age, where his appreciation for ancient artifacts, his attributed hat, whip as a weapon of choice, fear of snakes, and Harrison Ford’s real-life chin scar originate in the franchise’s continuum. Playing young Indiana, River Phoenix embodies what we would imagine a youthful Harrison Ford to be—agile, attractive, idealistic, slightly haphazard, perhaps overly self-assured, yet always charming. The sequence plays out like a Boy Scout Western straight out of a Boy’s Life magazine, with Phoenix’s comic Indy disrupting the robbery of the Cross of Coronado, chased on horseback by hired raiders, then across the top of circus train cars, and finally back home where his busy father waves-off his son’s impatience. Within Phoenix’s ten minutes of screen time, he embodies the character as singularly as Ford and, had his premature death not occurred in 1993, he would have been the perfect choice to continue the franchise in Ford’s footsteps.

Much of the humor in The Last Crusade comes, surprisingly, by way of Sean Connery and his uncharacteristic portrayal as a crotchety old intellectual and bumbling bookworm professor. Still, our moviegoer consciousness translates this casting as James Bond being the father of Indiana Jones, which in many ways was true (even if Connery is only twelve years older than Ford). After appearing briefly in the prologue, Henry Jones Sr. is not onscreen again until mid-film, having been kidnapped by Nazis. By this time, he has already bedded Indy’s Austrian guide Elsa Schneider (Alison Doody) and found the Grail’s location; only he has done so without his son’s adventurous spirit to spring him out of trouble, hence his capture by Nazi goons. Much to Connery’s pleasure and ours, Spielberg had no intention of exploiting a “James Bond meets Indiana Jones” gimmick with his casting. One adventurer was enough. Indeed, Jones Sr. is quite the opposite—Connery’s performance is a total reversal from his suave onscreen super-spy personality, offering up an unexpected comic gem in his studious, inept, intellectual type, from which his comparatively brash son has much yet to learn.

Much of the humor in The Last Crusade comes, surprisingly, by way of Sean Connery and his uncharacteristic portrayal as a crotchety old intellectual and bumbling bookworm professor. Still, our moviegoer consciousness translates this casting as James Bond being the father of Indiana Jones, which in many ways was true (even if Connery is only twelve years older than Ford). After appearing briefly in the prologue, Henry Jones Sr. is not onscreen again until mid-film, having been kidnapped by Nazis. By this time, he has already bedded Indy’s Austrian guide Elsa Schneider (Alison Doody) and found the Grail’s location; only he has done so without his son’s adventurous spirit to spring him out of trouble, hence his capture by Nazi goons. Much to Connery’s pleasure and ours, Spielberg had no intention of exploiting a “James Bond meets Indiana Jones” gimmick with his casting. One adventurer was enough. Indeed, Jones Sr. is quite the opposite—Connery’s performance is a total reversal from his suave onscreen super-spy personality, offering up an unexpected comic gem in his studious, inept, intellectual type, from which his comparatively brash son has much yet to learn.

But these humorous moments are never superfluous, unlike typical genre comic relief; rather, they add depth to the dynamic between Indy and his father. Watch the motorcycle chase where Indy runs down Nazi pursuers with his father in the sidecar. Our hero sends one Nazi spinning into the air and then smiles to his father for approval, who simply frowns in dissatisfaction and checks the time on his pocket watch. It’s a priceless screen moment. Through their interaction, we identify with the boyish and romantic reality of Indy’s existence, hunting treasure and fighting villains and getting The Girl. At the same time, his father represents the stuffy adult not tuned into the escapist nature of adventure. This distinction takes us back to the series’ origins, wherein those willing to embrace their Inner Child best relate to material so grounded in Saturday matinee serials; and so, who better to star in a serial emblem than Indiana Jones, an adolescent sort who embraces his Inner Child (and ours) with every new adventure. The presence of his father weakens the manly swashbuckler aspect of this Indiana Jones story. Still, it humanizes the hero, and in turn, transforms the character into a child, and in another way, links him with the raider from the film’s opening who gives Indy his signature fedora. Indy, then, combines his father’s scholarly appetites and those reinforced by his “second father” (played by bit actor Richard Young), a character with whom Indy identifies and unconsciously mirrors in the rebellion against his father. Furthermore, perhaps this is why Indy has changed his name from Henry Jr. to Indiana, “after the dog.”

Spielberg spearheaded this subplot, having explored father-son relationships reflective of his own broken rapport from childhood throughout his career. Moving with his father, Arnold, from Arizona to California after his parents divorced, Spielberg found his upbringing lonely and rough. His father’s presence was remote, leaving him ostensibly abandoned and left to focus on his obsession with cinema. Pursuing his dreams with unparalleled determination—motivated in part by his rumored Asperger’s Syndrome, a mild form of autism—Spielberg made it without the support of his father, earning himself a seven-year contract with Universal Studios by the time he was 22. Time and again, viewers see his films shot from the child’s point-of-view, both technically (with low angles) and thematically. It is impossible to watch the prologue in The Last Crusade—where Jones Sr. refuses to turn and look at his frantic son, who arrives with urgent news about the Cross of Coronado, until the boy counts to twenty, and in Greek no less—and not imagine Spielberg projecting his own experiences with a despondent father into the film.

Circumstances comparable to the lacking connection between Spielberg and his father arise in nearly all his films to a tragic degree: The father in Close Encounters of the Third Kind leaves his family behind in favor of his own obsessions; the family in E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial is broken by the conspicuous lack of a father figure; Empire of the Sun features a young Christian Bale left by his family to fend for himself when Japan invades China in 1937; Hook features a grown-up Peter Pan oblivious to his children until he rediscovers his childhood spirit; the children lost in Jurassic Park look to a reluctant and uninterested Alan Grant (Sam Neill) for fatherly protection; A.I. Artificial Intelligence reflects on a robot boy desperate for parental love, yet unable to genuinely find or express such emotions; Catch Me if You Can depicts Frank Abagnale Jr.’s dad as an irresponsible swindler who advocates his son’s con artist ways, while Jr. searches for a sturdy father figure even in the FBI agent chasing him; Minority Report takes the father’s perspective, as Tom Cruise’s character has lost his son and lives with the regret. Several other cases within Spielberg’s filmography show the director’s personal feelings influencing the story to meet his reflective emotional concerns; the above are simply the most clear-cut instances.

Circumstances comparable to the lacking connection between Spielberg and his father arise in nearly all his films to a tragic degree: The father in Close Encounters of the Third Kind leaves his family behind in favor of his own obsessions; the family in E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial is broken by the conspicuous lack of a father figure; Empire of the Sun features a young Christian Bale left by his family to fend for himself when Japan invades China in 1937; Hook features a grown-up Peter Pan oblivious to his children until he rediscovers his childhood spirit; the children lost in Jurassic Park look to a reluctant and uninterested Alan Grant (Sam Neill) for fatherly protection; A.I. Artificial Intelligence reflects on a robot boy desperate for parental love, yet unable to genuinely find or express such emotions; Catch Me if You Can depicts Frank Abagnale Jr.’s dad as an irresponsible swindler who advocates his son’s con artist ways, while Jr. searches for a sturdy father figure even in the FBI agent chasing him; Minority Report takes the father’s perspective, as Tom Cruise’s character has lost his son and lives with the regret. Several other cases within Spielberg’s filmography show the director’s personal feelings influencing the story to meet his reflective emotional concerns; the above are simply the most clear-cut instances.

Rarely does Spielberg allow for a ceasefire between father and son, leaving his narratives curiously cynical toward the prospect of reunion and resolution, even amid his signature sentimentality. And yet, The Last Crusade perfectly accomplishes this task, seemingly without effort, by symbolizing a sought-after truth in the historical and mythical journey to find proof of “the holy father” Jesus Christ via The Holy Grail. Through Jesus’ cup from The Last Supper, reconciliation is achieved between Christ and his Apostles, Christ and his own humanity, Christ and God, and finally Christ and the Crusader searching to find this fabled relic. The cup subsumes those designations within the film and strengthens them, providing magnitude to and profound allegory for the one adventure shared by Indiana Jones and his father. That Indy sees the Grail as a device to save his father in the end, as opposed to an important artifact, and allows it to drop back out of human reach, illustrates the film’s theme of family over objectivity. The MacGuffin becomes more than an excuse for action as The Ark of the Covenant and the Sankara Stones were in the previous Indiana Jones films; instead, it denotes an all-encompassing device that signifies our hero’s emotional journey as well as his literal one.

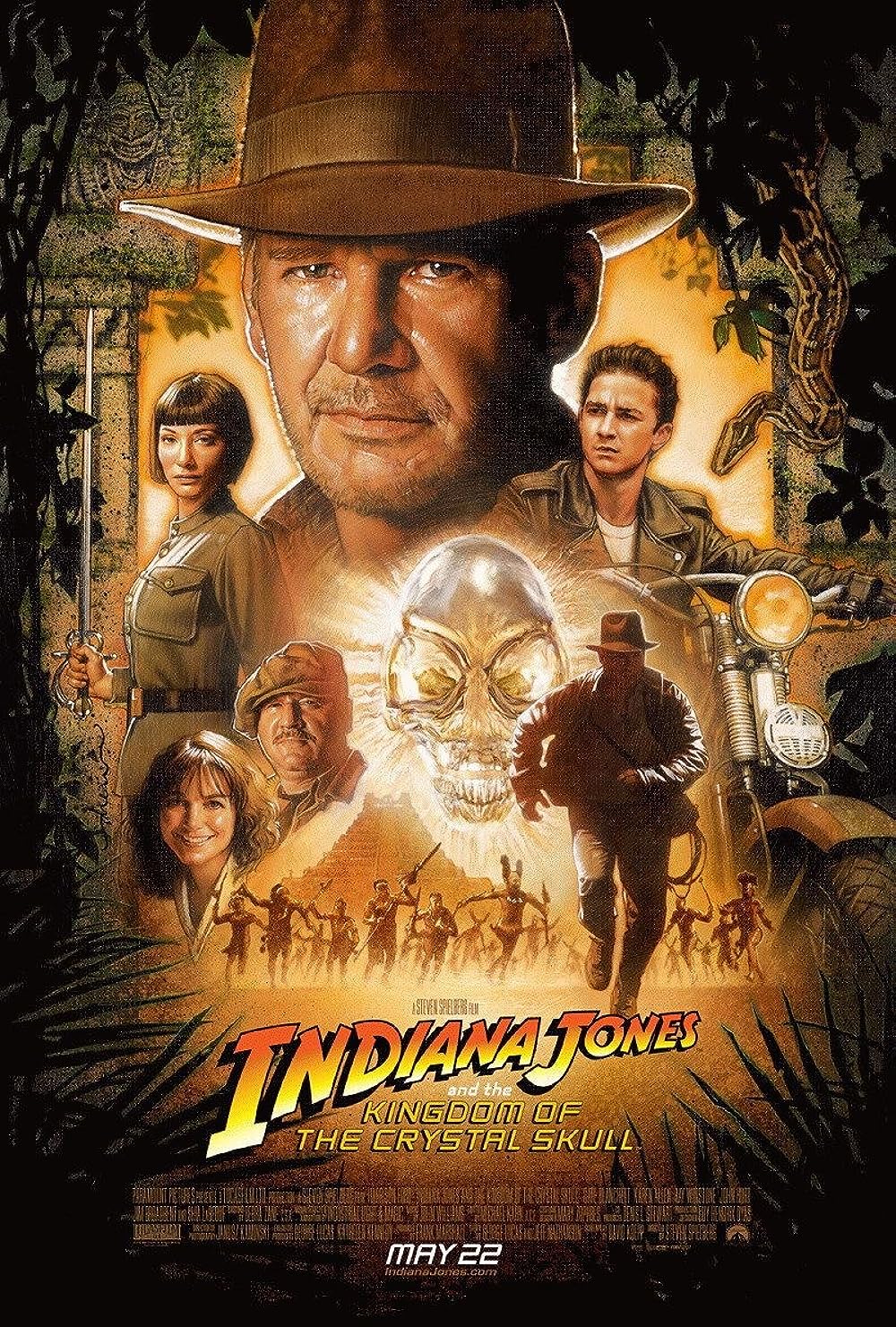

Of course, The Last Crusade’s emotional undercurrents should not imply this picture is devoid of action and suspense; on the contrary, like its predecessors, the film’s nonstop momentum moves from one setpiece to the next breathlessly, containing intrigue and thrills, and even a momentary run-in with Hitler himself. Once again, Indy faces creepy crawlies, this time in the form of rats in Venetian catacombs (it was snakes in Raiders of the Lost Ark; mounds of insects in Temple of Doom; flesh-eating ants in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull). The chases use every conceivable form of conveyance: boats, horses, cars, motorcycles, planes, tanks, and even a zeppelin. The story moves from Venice to Berlin to Hatay. It ends in a fantastical sequence where Indian Jones must pass a series of deathly traps before he meets the original crusader and chooses (wisely) the Grail from a hundred alternatives. It’s all arranged with Spielberg’s uncanny ability to make every moment appeal classical, while Ford and Connery bring their characters’ endearing relationship unexpected depth and humor.

When the conclusion of this final mission arrives, Indy’s newly earned appreciation for his father’s wisdom and bravery would seem to close out the film’s story arc, and perhaps so for the franchise as well. After all, the series does come “full circle” by incorporating characters from the first film, namely Marcus Brody (Denholm Elliott) and Sallah (John Rhys-Davies), as well as making Nazis the villains once more. It would be the perfect ending, wouldn’t it—Indy riding into the sunset with his father, both now immortal after having sipped from the Grail? Then again, there’s no existential theme running through Raiders of the Lost Ark and Temple of Doom to suggest these three stories are connected in any significant way; rather, they remain individual chapters, separate and distinct from one another. Indy’s look of admiration when Jones Sr. crashes an airplane with a flock of birds; his realization that his father’s quest for the Grail, which Indy believed hopeless, was indeed his own; his desperate actions to save his father’s life—these events bring closure, if not peace to the character. Though heavily publicized as the final Indiana Jones film, thanks to comments from both Lucas and Spielberg around the picture’s release in 1989, The Last Crusade is not necessarily the last crusade. Ford took a cue from his costar’s history as James Bond, admitting he would “never say never” to another sequel. Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull opened in theaters 19 years later.

When the conclusion of this final mission arrives, Indy’s newly earned appreciation for his father’s wisdom and bravery would seem to close out the film’s story arc, and perhaps so for the franchise as well. After all, the series does come “full circle” by incorporating characters from the first film, namely Marcus Brody (Denholm Elliott) and Sallah (John Rhys-Davies), as well as making Nazis the villains once more. It would be the perfect ending, wouldn’t it—Indy riding into the sunset with his father, both now immortal after having sipped from the Grail? Then again, there’s no existential theme running through Raiders of the Lost Ark and Temple of Doom to suggest these three stories are connected in any significant way; rather, they remain individual chapters, separate and distinct from one another. Indy’s look of admiration when Jones Sr. crashes an airplane with a flock of birds; his realization that his father’s quest for the Grail, which Indy believed hopeless, was indeed his own; his desperate actions to save his father’s life—these events bring closure, if not peace to the character. Though heavily publicized as the final Indiana Jones film, thanks to comments from both Lucas and Spielberg around the picture’s release in 1989, The Last Crusade is not necessarily the last crusade. Ford took a cue from his costar’s history as James Bond, admitting he would “never say never” to another sequel. Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull opened in theaters 19 years later.

If Raiders of the Lost Ark remains the series’ flawlessly balanced cinematic spectacle and Temple of Doom provides an ultra-simplification of suspense entertainment, this third entry in Spielberg’s enduring series places a vital humanity onto the series. If any characterizations are lacking in the previous films—“if” being the key term here—they become fleshed-out in this entry, making repeat viewings of the trilogy all the more effectual for the breakthroughs made therein. By association, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade betters what came before it and brings new layers to a singular character in the way only an exceptional sequel can. Spielberg’s most involved, personal entry into the franchise, The Last Crusade suggests there are still Indiana Jones adventures to be had outside of chasing after another in a long line of MacGuffins. Spielberg adds self-understanding to the character’s existing pantheon of great adventures by unearthing mysteries within our hero seemingly entombed and just waiting to be excavated.

Bibliography:

Friedman, Lester D. Citizen Spielberg. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

McBride, Joseph. Steven Spielberg (Third Edition). London. Faber and Faber, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review