The Definitives

House of Games (1987)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

David Mamet is a magician whose tools are the natural illusions of character and mood. As writer and director, Mamet has no need for flashy computer effects, pyrotechnics, or complex visual demonstrations because his magic resides in precisely crafted dialogue, terse screenwriting, and a spare visual and narrative style. The playwright and author meticulously plans how every actor will say each line in his “Mametspeak,” as it has been dubbed, and does not waste a word. We cannot take a single moment or line in his films for granted, and only when we have observed his cinematic act in totality and can reflect upon it do we recognize the scope of his magic show. Mamet’s 1987 directorial debut House of Games takes the shape of an elaborately staged confidence game, or simply “The Con,” a motif often used in his subsequent films. In the picture, he bestows his confidence in the viewer, helping us believe we’re smart enough to keep up. We trust that he’ll take the narrative where it will impliedly go. But all at once a turn occurs, changing everything in the film, reshaping everything we’ve seen and heard. This leads to another Mametism: giving the viewer the illusion of control, of understanding, when of course we have none. We are afforded false security as members of Mamet’s audience, like spectators to a master illusionist. Mamet seems to be generous in what he shares with us, except in reality he gives up nothing, and the film is far more complex than we can imagine.

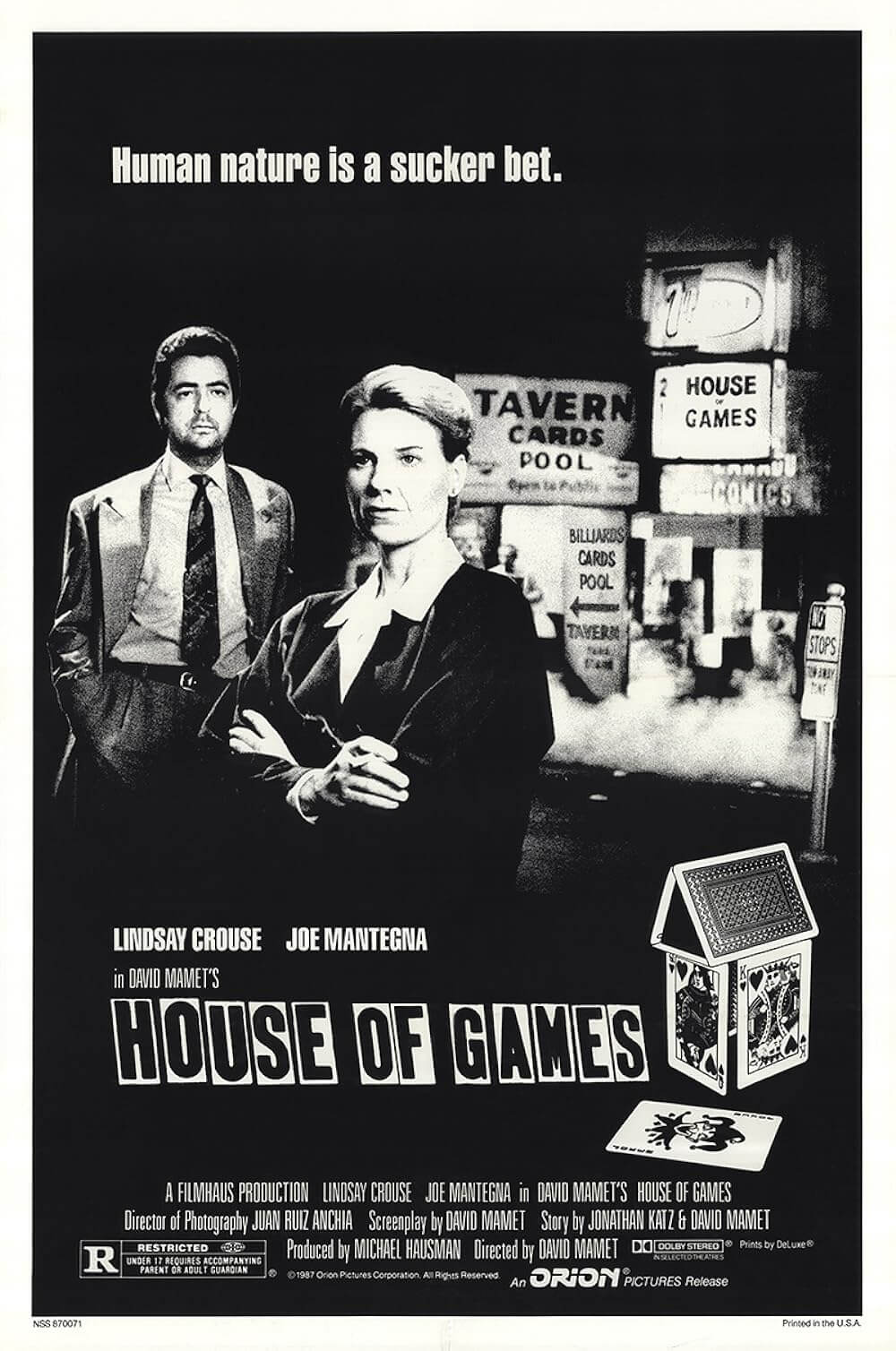

House of Games is a moody and twisting crime story about con artists, wet city streets at night, steaming manhole covers, and smoky game rooms in the back of shady pool halls. All of these familiar atmospherics conceal, and later reveal, the truths in an entrenched character study, the major plot details of which this analysis will not discuss to preserve Mamet’s twists and turns. The film centers on Margaret Ford (Lindsay Crouse), a practicing psychiatrist and author who subsists behind cold ambiguity. The first scene shows Margaret signing her new book called “Driven”, a psychiatric study of obsessive compulsion, for a fan. From this onset, we can plainly see how Mamet demanded that Crouse mute her emotions. In both his stage and screen drama, Mamet believes there is no need for “feeling” in his dialogue; accordingly, Crouse’s speech is so blank that it’s almost monotone, her presence all but empty. Meaning is given through words, or lack thereof, as opposed to how they are spoken or inflected by the actor. Crouse has been criticized for these early scenes, since her acting is pointedly deficient of expression. She barely smiles and speaks like an automaton; her body language is static, signifying neither introversion nor extroversion, nor typically male or female traits—Crouse gives an asexual performance. Her wardrobe is unflattering, unsexy, and her status as a female in the film’s pointedly male world is of no consequence. Her appearance and behavior suggest Dr. Margaret Ford has control over her emotions, unlike her subjects, whom we see range from an insane murderer to a suicidal, habitual gambler.

But then Margaret meets Mike Manusco (Joe Mantegna), a gambler of sorts, in an attempt to “save” one of her patients who owes Mike a gambling debt. Mike, a card player and “bad boy”, sizes up Margaret before they speak, and he agrees to write off her patient’s debt if she does him a favor. In Mike’s current poker game, his opponent, a Las Vegas card shark named George (Ricky Jay), has a “Tell” or giveaway. By reading the Tell, Mike can see if the gambler is bluffing, giving Mike the advantage, thus winning him a large pot. Since the gambler knows Mike has seen his Tell, when Mike leaves the room, Margaret can watch for it, inform Mike if it occurred, and assist him in winning the hand. Except, the Tell proves wrong and Mike loses. George wants his victory money, six-thousand dollars, which Mike cannot cover. And when the card shark pulls a gun and makes threats, Margaret does not hesitate to take out her checkbook and give a complete stranger her money. The card shark calms and sets his gun on the poker table as Margaret writes the check, and in that moment she notices it leaking water from the barrel. She has been—or has come very close to being—conned. The jig is up. Mike and George, along with their partner Joey (Mike Nussbaum), give up the act and casually, if not charmingly, dismiss the incident as “just business”. Margaret can only laugh. But from here, she’s pulled deeper into Mike’s world of professional deceit.

But then Margaret meets Mike Manusco (Joe Mantegna), a gambler of sorts, in an attempt to “save” one of her patients who owes Mike a gambling debt. Mike, a card player and “bad boy”, sizes up Margaret before they speak, and he agrees to write off her patient’s debt if she does him a favor. In Mike’s current poker game, his opponent, a Las Vegas card shark named George (Ricky Jay), has a “Tell” or giveaway. By reading the Tell, Mike can see if the gambler is bluffing, giving Mike the advantage, thus winning him a large pot. Since the gambler knows Mike has seen his Tell, when Mike leaves the room, Margaret can watch for it, inform Mike if it occurred, and assist him in winning the hand. Except, the Tell proves wrong and Mike loses. George wants his victory money, six-thousand dollars, which Mike cannot cover. And when the card shark pulls a gun and makes threats, Margaret does not hesitate to take out her checkbook and give a complete stranger her money. The card shark calms and sets his gun on the poker table as Margaret writes the check, and in that moment she notices it leaking water from the barrel. She has been—or has come very close to being—conned. The jig is up. Mike and George, along with their partner Joey (Mike Nussbaum), give up the act and casually, if not charmingly, dismiss the incident as “just business”. Margaret can only laugh. But from here, she’s pulled deeper into Mike’s world of professional deceit.

Margaret exists in a kind of limbo where she feels helpless to assist her far-gone patients. She has attained success with her book on compulsion and has come to realize that truly helping people is a delusion. She preaches to her patients that they should take control of their lives, but she remains unhappy and unfulfilled in her own, as revealed in her conversations with her mentor and colleague, Dr. Maria Littauer (Lila Skalia). She documents the lives of others and talks about life but does not participate; as a psychiatrist, she observes, records, and asks endless questions. Dr. Littauer tells her to have fun, to escape the pressures of her work by doing something she enjoys. And so, she escapes back to Manusco’s gambling lair, called “House of Games”, and pushes herself nearer to the cusp of self-revelation within a den of thieves. She’s drawn to Mike’s behavior: he’s charismatic and dangerous, and she’s thrilled by it. She proposes that he be the subject of her next book—a look into the world of bad men, con men. Indeed, Mamet has carefully constructed Margaret as a repressed “bad girl”, hinting at her own greater internal conflicts, often overlooked by the film’s audiences otherwise preoccupied by aspects of The Con. Reading reviews for House of Games, one finds that few of them mention the subtleties of Crouse’s performance, mistaking her lack of evocation as poor acting. Rather, she follows Mamet’s faultless description and direction. Margaret chain smokes, and so Mamet shoots several filled ashtrays, relating that she wrote “Driven” based on personal knowledge. She repeatedly “cracks out of turn” (a Freudian slip), which Crouse verbally underlines, her pattern of slippages significant in the climactic scene, making Crouse’s emphasis curious in its spoken moment, but important later on.

Margaret is an assemblage of emergent compulsions and obsessions. Notice that when she sleeps—we see this twice within the film—it is only on couches. Conceivably, this is an indication of her claustrophobia; she resists sleeping where she is intended to, as the very idea is confining. We also see that her desk is turned toward the window, her back awkwardly facing her office door. Her claustrophobia demands that she look out a window to see open space, rather than looking up at the confines of her office. Furthermore, in two instances Margaret feels the need to escape: The first instance occurs in a mental institution where she interviews a disturbed subject. As she leaves and the attendant labors to find the correct key to open the barred door, Margaret twitches with unease until it opens. Another instance comes about in a hotel room, where an undercover cop pulls his badge and intends to arrest Margaret and Mike. Margaret turns to Mike and says with desperation, “I’ve gotta get out of here!” Mike rushes the cop. Margaret dashes for the door on tenterhooks to get away, only in their tussle Mike and the cop block her leaving. A glint of light shines on her face, over her eye—escape is in sight, yet urgently unattainable. Margaret also suffers from kleptomania, the symptoms of which become Mamet’s most concentrated warning sign. Her compulsion is handed over from Mike, who, after they make love in another man’s hotel room, suggests that when people are fired they should steal something from their place of employment to feel superior. She looks over treats belonging to the room’s occupant: some cash, a comb, cigars and so forth are strewn out on a dresser. She finds a pocket knife and holds it as if it were a precious thing. When Mike reenters the room, she quickly hides it away in her pocket. Another compulsion is born.

Margaret is an assemblage of emergent compulsions and obsessions. Notice that when she sleeps—we see this twice within the film—it is only on couches. Conceivably, this is an indication of her claustrophobia; she resists sleeping where she is intended to, as the very idea is confining. We also see that her desk is turned toward the window, her back awkwardly facing her office door. Her claustrophobia demands that she look out a window to see open space, rather than looking up at the confines of her office. Furthermore, in two instances Margaret feels the need to escape: The first instance occurs in a mental institution where she interviews a disturbed subject. As she leaves and the attendant labors to find the correct key to open the barred door, Margaret twitches with unease until it opens. Another instance comes about in a hotel room, where an undercover cop pulls his badge and intends to arrest Margaret and Mike. Margaret turns to Mike and says with desperation, “I’ve gotta get out of here!” Mike rushes the cop. Margaret dashes for the door on tenterhooks to get away, only in their tussle Mike and the cop block her leaving. A glint of light shines on her face, over her eye—escape is in sight, yet urgently unattainable. Margaret also suffers from kleptomania, the symptoms of which become Mamet’s most concentrated warning sign. Her compulsion is handed over from Mike, who, after they make love in another man’s hotel room, suggests that when people are fired they should steal something from their place of employment to feel superior. She looks over treats belonging to the room’s occupant: some cash, a comb, cigars and so forth are strewn out on a dresser. She finds a pocket knife and holds it as if it were a precious thing. When Mike reenters the room, she quickly hides it away in her pocket. Another compulsion is born.

Any power that could elevate Margaret above her patients, or Mike, is denied by her kleptomaniac’s guilt. This is Margaret’s internalized throughline: her acceptance of her own compulsions and obsessions is her character’s arc. Dr. Littauer suggests that when someone has done something awful or unforgivable, they must forgive themselves. In the film’s climax, she confronts Mike at gunpoint. “You took my money,” she says. “You raped me. You took me under false pretenses… You used me.” She puts a bullet in his leg to let him know she’s serious. “I want you to beg me” she says and fires again. “I can’t help it—‘I’m out of control.’” But in that moment she has absolute control; she’s prepared to forgive herself for whatever she may do. After killing Mike, House of Games finds Margaret after a vacation, meeting Dr. Littauer at a restaurant for some lunch. She has long since forgiven herself for her misdeeds throughout the narrative. Self-clemency washes away whatever crimes she may have committed, giving way to a guilt-free, amoral existence. The beautiful, dark last scenes show Margaret taking control of her life, becoming a participant, no longer a victim of Mike and his crew’s elaborately conceived con game. She forgives herself for whatever she may do compulsively. In the final moment, she asks a fellow restaurant patron to identify the dish on the buffet opposite her, and as the patron glances away Margaret reaches into the woman’s purse to lift a gold lighter, a token which she cradles underneath the table like a treasure, and then uses it to light herself a cigarette.

Mamet grew up in Chicago where he began a career writing for the stage. His Off-Broadway plays Sexual Perversity in Chicago (later made into the film About Last Night…, 1986) and American Buffalo (adapted to film in 1996) gained him instant acclaim in the late 1970s. By then he had founded his own theater company and taught drama at Vermont’s Goddard College, where he had graduated in 1969. While in Chicago, Mamet was introduced to a number of his later stock company, including players Joe Mantegna and William H. Macy. He began writing scripts early in his career, beginning in 1981 with an adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice, starring Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange, in a lusty interpretation of the already classic film. The next year, he wrote The Verdict for Sidney Lumet, another adaptation, but this time he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. His 1984 play Glengarry Glenn Ross earned Mamet the Pulitzer Prize for drama, forever making him a credible voice on the American stage. And in the subsequent years Mamet worked as Hollywood’s go-to script doctor, sometimes taking uncredited work, such as rewriting John Frankenheimer’s last great film Ronin under the name “Richard Weisz”. Within credited scripts for The Untouchables, Hoffa, The Edge, and Wag the Dog, we see signs of Mamet’s dialogue guiding other directors to focus on words rather than the action responding to them. Although a counter-intuitive approach for other filmmakers, an austerity of words and visuals would become the defining characteristic of Mamet’s own films.

Mamet grew up in Chicago where he began a career writing for the stage. His Off-Broadway plays Sexual Perversity in Chicago (later made into the film About Last Night…, 1986) and American Buffalo (adapted to film in 1996) gained him instant acclaim in the late 1970s. By then he had founded his own theater company and taught drama at Vermont’s Goddard College, where he had graduated in 1969. While in Chicago, Mamet was introduced to a number of his later stock company, including players Joe Mantegna and William H. Macy. He began writing scripts early in his career, beginning in 1981 with an adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice, starring Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange, in a lusty interpretation of the already classic film. The next year, he wrote The Verdict for Sidney Lumet, another adaptation, but this time he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. His 1984 play Glengarry Glenn Ross earned Mamet the Pulitzer Prize for drama, forever making him a credible voice on the American stage. And in the subsequent years Mamet worked as Hollywood’s go-to script doctor, sometimes taking uncredited work, such as rewriting John Frankenheimer’s last great film Ronin under the name “Richard Weisz”. Within credited scripts for The Untouchables, Hoffa, The Edge, and Wag the Dog, we see signs of Mamet’s dialogue guiding other directors to focus on words rather than the action responding to them. Although a counter-intuitive approach for other filmmakers, an austerity of words and visuals would become the defining characteristic of Mamet’s own films.

After The Verdict, Mamet had seen enough film sets and productions to know he wanted to direct his own scripts. He wrote House of Games for Crouse, his wife at the time, but no studio would buy it because they felt the story was too dark. Once Crouse was nominated for an Oscar for Places in the Heart (1984) and producer Michael Hausman called in a favor at Orion Pictures, Mamet’s first directorial feature was underway. He cast from his Chicago stock. Mantegna, who had starred and earned a Tony Award for his stage performance in Glengarry Glenn Ross, was passed over for the play’s eventual film adaptation in favor of Al Pacino when Mamet sold the rights (the eventual picture in 1992 was an excellent adaptation directed by James Foley). To make up for it, Mamet offered Mantegna two scripts, first House of Games and then Things Change (1988), and the actor would also star in Mamet’s third feature, Homicide (1991). Other actors—such as Jack Wallace, J.T. Walsh, Steven Goldstein, and Macy—would become regulars in his films. For the playwright and screenwriter, Mamet’s leap to film director involved much pre-planning based on the theories of Sergei Eisenstein, so that the entire film was plotted out in a careful shot-by-shot logic. Alongside Hausman and cinematographer Juan Ruiz Anchía, Mamet completed production carefully and self-consciously, finishing on time and under budget within the short 49-day shooting schedule. Throughout, he achieved a visual style that echoed the method of his dialogue, leaving any evocative substance intentionally under-emphasized and up to the viewer to discover.

Mamet’s signature is his dialogue, as it is often the point on which audiences accept or deny his work. Using sometimes untraceable plays on words, his characters speak in amalgamated clichés, manipulated so that their meaning changes given the context. The line “Thank you, sir, may I have another?” in House of Games is both ironic and tragic given its placement during Mike’s death scene. Or there’s the line, “South Street Seaport the man says” during a poker game, which refers to a pointedly New York-based character who in this line nods to his familiarity with Manhattan’s South Street Seaport, yet places emphasis on the poker term “south”, meaning to fold. In other scenes, Mamet adds weight onto a specific word or phrase and adjusts its meaning. He encircles entire strings of conversation around the meaning of words, such as when Mike explains The Con to Margaret, saying “It’s called a confidence game. Why? Because you give me your confidence? No. Because I give you mine.” Concentration on a word such as “confidence” as an idea lends to Mamet’s use of repetition, which is more like a pulse or musical tempo than reiteration. Filled with half-finished sentences and assumed thoughts, he forces us to consider the power of language and the facts of the situation. We are meant to deliberate over intended and possible meanings conveyed in Mamet’s language, and so his words, more so than visuals or actors, are the most important element in his pictures.

Mamet’s signature is his dialogue, as it is often the point on which audiences accept or deny his work. Using sometimes untraceable plays on words, his characters speak in amalgamated clichés, manipulated so that their meaning changes given the context. The line “Thank you, sir, may I have another?” in House of Games is both ironic and tragic given its placement during Mike’s death scene. Or there’s the line, “South Street Seaport the man says” during a poker game, which refers to a pointedly New York-based character who in this line nods to his familiarity with Manhattan’s South Street Seaport, yet places emphasis on the poker term “south”, meaning to fold. In other scenes, Mamet adds weight onto a specific word or phrase and adjusts its meaning. He encircles entire strings of conversation around the meaning of words, such as when Mike explains The Con to Margaret, saying “It’s called a confidence game. Why? Because you give me your confidence? No. Because I give you mine.” Concentration on a word such as “confidence” as an idea lends to Mamet’s use of repetition, which is more like a pulse or musical tempo than reiteration. Filled with half-finished sentences and assumed thoughts, he forces us to consider the power of language and the facts of the situation. We are meant to deliberate over intended and possible meanings conveyed in Mamet’s language, and so his words, more so than visuals or actors, are the most important element in his pictures.

But for every economic use of words, there is an equally economic use of action. Offering instruction on his approach, Mamet wrote essays and taught screenwriting, most notably in the book On Directing Film, taken from Mamet’s time lecturing at Columbia University, which features some of the best, harshest advice young directors should consider when writing and directing a movie. In his lectures, he talks at length about not necessarily showing the audience actions or time, but rather denoting them with detail. For example, in Mamet’s 2004 film Spartan the camera briefly passes over a broken door frame and inside cops stand about: This tells us a raid has occurred. Showing the raid is a pointless piece of action, unimportant to the story; the information derived from the raid—that’s the meat, which Mamet is so eager to cut into. As a result, Mamet shows action sparingly. But as much as he calls attention to his dialogue, to the seemingly open facts of a situation as it applies to the conversations and “meat” of the story, he uses that apparent openness like a magician, misdirecting his audience. Off-screen, Mamet has made a habit of surrounding himself with real-life gamblers, con men, and magicians that would later inform House of Games’ unflinching authenticity, and the director’s own approach to narrative structure.

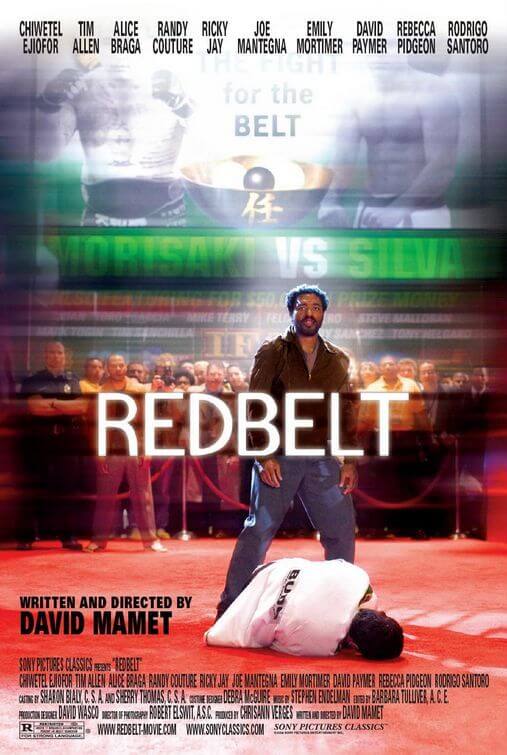

Ricky Jay, another of Mamet’s reserve of film actors, was the magic consultant on films like The Prestige and The Illusionist, both released in 2006. At the age of 4, Jay made his first appearance as a stage magician in 1953 and has spent the better part of 65 years researching and mastering the techniques of history’s greatest illusionists, sleight-of-hand experts, grifters, card sharks, conjurers, and swindlers. For House of Games, Jay divulged tricks of the trade—old tricks to him, new to us—to be demonstrated, particularly the ins and outs of various Short Con strategies. Mamet uses Jay’s teachings directly and philosophically. Although a number of clever deceptions are detailed in the film, the story itself is dramatic sleight-of-hand, where Mamet’s one hand fascinates us with the sordid dealings of Mike’s con artist bunch, while in the other hand Mamet holds Margaret’s revelatory ace and reveals it in the final scenes. Mamet’s films involve all kinds of cons of this sort and never are they limited to just poker, heists, double-crosses, et cetera. In his comedy State and Main (2000), we see a Hollywood film crew tempt an idealistic screenwriter, swindling him with words, promises, and fame—a moral con—until his ideals match their own. With Homicide, perhaps Mamet’s most underappreciated masterpiece, a detective’s personal code is turned inside-out by his newfound dedication to Judaism. In The Spanish Prisoner (1997), a sort of younger brother to House of Games, Mamet makes every frame another clue in a con of corporate intrigue. Or there’s the structure of the aforementioned Spartan, where Mamet resists revealing the vital name or identity of a central kidnappee for much of its runtime.

Ricky Jay, another of Mamet’s reserve of film actors, was the magic consultant on films like The Prestige and The Illusionist, both released in 2006. At the age of 4, Jay made his first appearance as a stage magician in 1953 and has spent the better part of 65 years researching and mastering the techniques of history’s greatest illusionists, sleight-of-hand experts, grifters, card sharks, conjurers, and swindlers. For House of Games, Jay divulged tricks of the trade—old tricks to him, new to us—to be demonstrated, particularly the ins and outs of various Short Con strategies. Mamet uses Jay’s teachings directly and philosophically. Although a number of clever deceptions are detailed in the film, the story itself is dramatic sleight-of-hand, where Mamet’s one hand fascinates us with the sordid dealings of Mike’s con artist bunch, while in the other hand Mamet holds Margaret’s revelatory ace and reveals it in the final scenes. Mamet’s films involve all kinds of cons of this sort and never are they limited to just poker, heists, double-crosses, et cetera. In his comedy State and Main (2000), we see a Hollywood film crew tempt an idealistic screenwriter, swindling him with words, promises, and fame—a moral con—until his ideals match their own. With Homicide, perhaps Mamet’s most underappreciated masterpiece, a detective’s personal code is turned inside-out by his newfound dedication to Judaism. In The Spanish Prisoner (1997), a sort of younger brother to House of Games, Mamet makes every frame another clue in a con of corporate intrigue. Or there’s the structure of the aforementioned Spartan, where Mamet resists revealing the vital name or identity of a central kidnappee for much of its runtime.

With Mamet, every film is a con game, a magic show of words, and in them a dramatic revelation. House of Games is not about following twists; it’s about following a character whose self-deception and an eventual acceptance of her own criminal behavior is more dangerous than any of the various cons within the film. Its structure deceives and consumes us with Margaret’s adventures alongside bad men, her role that of a victim who takes control to become self-possessed. The Con relies on giving a trust which is ultimately abused; in Margaret’s case, The Con supplies her patients with the impression that her psychiatric opinion will help them when she knows it will not. She swindles her patients into believing they need her. In that respect, House of Games is a film about a psychiatrist who accepts this, who accepts that her profession is a con game. Indeed, she is already a con artist when the film begins, she just doesn’t know it yet. After being conned herself, Margaret makes this realization, and therefore, later on, she accepts her own compulsions, her obsessions, and her daily deceit of her patients. In turn, Mamet cons the viewer, suggesting the film’s narrative surrounds our understanding of The Con from films like The Sting (1973) or Matchstick Men (2003). But not every con game involves playing cards and big money deals. Sometimes the greatest con game of them all is how we justify our actions to ourselves and others.

In House of Games and beyond, Mamet’s characters are conduits for his dialogue, which, more than his minimalist camerawork, costumes, or art direction, is the apex of his films. Within cinema’s pointedly visual medium, a small number of directors have commanded audiences to focus on words rather than pictures. Mamet’s wordsmithing chimes like visceral poetry, keeping tempo as the film’s percussion, making his voice one of the most pronounced in modern film. Despite Mamet’s focus on words, the dialogue in House of Games is layered in deception and refrains from disclosure, admits nothing forthright, and yet tells us everything we need to know. We pick up clues along the way, always watching the magician’s hands, certain we’ll pick up on his particular method of trickery. But a good magician points out what he’s doing and tells the audience what they should see, and at the last moment he does something unexpected, something right under our noses, something which we never could have conceived. In the cinema of David Mamet, for every revelation there is another element underneath each new surface, and so confessions seem temporary, even when they are true. And because of this intricacy, House of Games remains a richly conceived character study, a complex cinematic con game, and above all else a grand magic act.

In House of Games and beyond, Mamet’s characters are conduits for his dialogue, which, more than his minimalist camerawork, costumes, or art direction, is the apex of his films. Within cinema’s pointedly visual medium, a small number of directors have commanded audiences to focus on words rather than pictures. Mamet’s wordsmithing chimes like visceral poetry, keeping tempo as the film’s percussion, making his voice one of the most pronounced in modern film. Despite Mamet’s focus on words, the dialogue in House of Games is layered in deception and refrains from disclosure, admits nothing forthright, and yet tells us everything we need to know. We pick up clues along the way, always watching the magician’s hands, certain we’ll pick up on his particular method of trickery. But a good magician points out what he’s doing and tells the audience what they should see, and at the last moment he does something unexpected, something right under our noses, something which we never could have conceived. In the cinema of David Mamet, for every revelation there is another element underneath each new surface, and so confessions seem temporary, even when they are true. And because of this intricacy, House of Games remains a richly conceived character study, a complex cinematic con game, and above all else a grand magic act.

Bibliography:

Mamet, David. House of Games: The Complete Screenplay. New York: Grove Press, 1987.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review