The Definitives

His Girl Friday (1940)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

One has to wonder if newspapermen like the ones in His Girl Friday ever existed, or if the films like these created the stereotype. You know the sort: fast-talking, hard-nosed reporters willing to do anything for a scoop; they quip with Smithy the typesetter or Sweeny the fact-checker; their fedoras rest on the back of their head as they dictate wispy prose to themselves while punching keys into their typewriter for last-minute inclusion to the evening edition. Though Howard Hawks’ archetypal 1940 comedy was based on the 1928 stage play The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, the film became even more popular than its source for its romantic trimmings, and later played a crucial role in establishing Hollywood’s notions of what goes on behind-the-scenes at a newspaper. Moreover, Hawks’ film also remains one of the most enduring of all those frenzy-paced screwball comedies, a genre that the director himself helped establish.

Adapted for the screen by Charles Lederer for Hawks, His Girl Friday was not the only rendition of the newspaper play. It had already been turned into a motion picture in 1931 by Lewis Milestone, which took the play’s name and starred Adolphe Menjou and Pat O’Brien. Years later in 1974, Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau starred in yet another version, while Burt Reynolds and Kathleen Turner appeared in the decidedly less edgy television-themed version in 1988, called Switching Channels. And yet, time has forgotten those other adaptations in place of the singularly romantic and razor-witted stylings of His Girl Friday, the first and most sophisticated version, which replaced what was originally two male leads with a male editor and his ace-reporter ex-wife. Hawks conceived the change, and with a simple flip of gender, he adds the most affecting layer and an all-encompassing romantic importance to the story, allowing for this newspaper yarn to evolve and play alongside a biting romantic comedy.

As the story goes, Hawks wanted to prove that The Front Page still contained some of the best dialogue ever written. He demanded a reading with two actors, one playing editor Walter Burns and the other reporter Hildy Johnson, but only one actor was available, so he gave the play to his secretary and asked her to read the Hildy role. At that moment, Hawks proclaimed that the play would be re-written in a new screen version with a man and woman in the two central roles. After Hecht approved the alteration to his material, he and Hawks began work on the revised concept in 1939, until Hecht’s friend Lederer suggested not only that the character of Hildy be changed to female, but that the story focus more closely on the idea that Walter and Hildy were previously married and divorced, and that Hildy was now getting married to another man. Hecht was eventually forced to move on to another project, leaving the majority of the writing on the working title, The Bigger They Are, to Lederer, who received sole screen credit with Hecht’s consent. Although, uncredited punchlines have been attributed to Morrie Ryskind, who adapted The Cocoanuts (1929) for the Marx Brothers.

Casting a leading man was effortless for Hawks, with Cary Grant as his first and only choice to play Walter Burns, the hard-edged editor of The Morning Post. Grant had already starred in two films for the director: the screwball classic Bringing Up Baby (1938) and the airplane drama Only Angels Have Wings (1939). For the general public, the actor’s name was synonymous with blithe comedies, having achieved his popularity with Leo McCarey’s The Awful Truth (1937), even though his career diverted into an occasional heroic, debonair act in fare like In Name Only and Gunga Din (both from 1939). His screwball characterization would last him until the end of his career—even, in a way, in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest—with a few rare diversions (such as Hitchcock’s Notorious and Suspicion) that were met with sometimes bewildered responses. At least in comparison to Bringing Up Baby before or Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) after, His Girl Friday would mark a measured comedic performance from Grant, though perfectly suited to the actor’s charms and penchant for ad-libbing.

Finding the right woman to play Hildy Johnson was a far more involved process, as Hawks offered the role to several high-profile actresses before eventually settling on a leading lady. At the outset, Hawks wanted Carole Lombard, whose screwball talent had been popularized with Hawks’ own Twentieth Century (1934). But the director was forced to look elsewhere when the studio could not accommodate Lombard’s considerable salary requirements. Along with Katharine Hepburn, Jean Arthur, Claudette Colbert, Irene Dunne, and Ginger Rogers, who all either turned down the part or could not accept for a range of reasons, Lombard made way for Rosalind Russell. Versed in fast-paced comedy from appearances in Four’s a Crowd (1938) and The Women (1939), Russell was perfectly suited for the role. Yet, according to Life Is A Banquet, Russell’s autobiography, Hawks, having to settle for not his ideal choice of actress, treated her with disdain those first days of shooting. In a way that only the high-heeled and no-nonsense Russell could, she confronted her director. “You don’t want me, do you?” she asked him. “Well, you’re stuck with me, so you might as well make the most of it.” Whatever first-round misgivings Hawks had about Russell must have settled, as he directed her Hildy into one of the strongest female characters in all of cinema, a role that in 1940 was close to unprecedented.

Hawks stages an exceptional battle of wits and sexual politics between Grant and Russell, two performers matched in their capacity to hurl verbal jabs with machine-gun speed. Russell’s Hildy Johnson wants out of the newspaper game to marry her dopey insurance salesman fiancé, Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy), and make a family in Albany. She arrives at the Morning Post’s offices to tell her editor, Grant’s Walter Burns, of her plans to wed Baldwin the next day after catching a train that evening. With little time to maneuver, Burns concocts a scheme to keep her around, in part because his paper needs her sharp reporting, and also because he still loves her. “Oh, she’s staying,” Burns quips. “She just doesn’t know it yet.” His biggest hook is the execution of Earl Williams (John Qualen), a cop-killer who should have been tried with an insanity plea. Should the Morning Post cover the story, they could save Williams’ life and simultaneously rub out the careers of the corrupt Mayor (Clarence Kolb McCue) and his ineffectual sheriff (Gene Lockhart). Burns dangles the story in front of Hildy, lays an effective guilt trip on Baldwin, and Hildy eventually agrees to write one last story—in exchange for Burns signing a life insurance policy with Baldwin that will provide the new couple a financial nest egg. After Hildy interviews Williams to play up the insanity angle, the prisoner escapes, creating a frenzy of newspapermen trying to get the scoop. Working together again with Burns to get the story makes Hildy realize she still loves being a reporter and still loves Burns too.

However, the broad strokes of the plot are not what make His Girl Friday a great film; the speed and humor of the dialogue and the performances do. Lederer’s final screenplay contained a hefty 191 pages, yet the film runs only 92 minutes. And though screenwriting tenets state a page equals a minute of screentime, Hawks escalates the dialogue to an incredible speed, with almost ceaseless overlapping. In an interview with Peter Bogdonovich, Hawks explained, “I had noticed that when people talk, they talk over one another, especially people who talk fast or who are arguing or describing something. So we wrote the dialog in a way that made the beginnings and ends of sentences unnecessary.” But this was before the days of multi-track recordings, which meant sound mixers followed the actors with several microphones, switching each one on and off as the actors exchanged their dialogue. Such an approach required a refined sense of timing between the actors, director, and sound department that, when watching the film, the whole effect displays an unprecedented degree of control in scenes that are meant to play as haphazard commotion. For the many ad-libbed scenes, the sound department required even more care.

However, the broad strokes of the plot are not what make His Girl Friday a great film; the speed and humor of the dialogue and the performances do. Lederer’s final screenplay contained a hefty 191 pages, yet the film runs only 92 minutes. And though screenwriting tenets state a page equals a minute of screentime, Hawks escalates the dialogue to an incredible speed, with almost ceaseless overlapping. In an interview with Peter Bogdonovich, Hawks explained, “I had noticed that when people talk, they talk over one another, especially people who talk fast or who are arguing or describing something. So we wrote the dialog in a way that made the beginnings and ends of sentences unnecessary.” But this was before the days of multi-track recordings, which meant sound mixers followed the actors with several microphones, switching each one on and off as the actors exchanged their dialogue. Such an approach required a refined sense of timing between the actors, director, and sound department that, when watching the film, the whole effect displays an unprecedented degree of control in scenes that are meant to play as haphazard commotion. For the many ad-libbed scenes, the sound department required even more care.

Of course, the film requires multiple viewings to catch every line, as contagious laughter overpowers the dialogue. Hawks refuses to slow the procession of lines as well, leaving quick nods to Archie Leech (Grant’s real name) and a reference to the escaped Williams hiding in a roll-top desk as a “Mock Turtle” (Grant’s character in the 1933 version of Alice in Wonderland). Other self-referential lines were inserted by the main players, each of whom contributed to the script on a daily basis. Grant, for example, described Bruce Baldwin with the impromptu line “He looks like that fellow in the movies, you know…Ralph Bellamy.” Though Columbia Pictures studio head Harry Cohn balked at much of the improvisation, Hawks encouraged it on the set, creating healthy competition between Grant, who was versed in fast-talking improv from earlier comedies, and Russell, who was so intent to keep up with her costar that she hired a personal writer to give her dialogue some edge. Each morning Grant welcomed Russell to the set, asking “What have you got today?” That rivalry is felt onscreen throughout the constant banter of the two leads.

Beyond screwball laughs, Hawks also delivers the quintessential newspaperman film with His Girl Friday, which claims to be merely a depiction of long-gone journalistic misconduct, yet instead represents an enduring trend in the media. After the opening credits, titles appear and read: “It all happened in the ‘Dark Ages’ of the newspaper game—when a reporter ‘getting the story’ justified anything short of murder. Incidentally, you will see in this picture no resemblance to the men and women of the press today.” Hecht and MacArthur were newspapermen and covered hangings in the heyday of yellow journalism, spinning stories to their liking; but they also knew that their scenario was still relevant upon its release on stage, and would continue to be relevant—news media will forever be subjective, where an author ignores or chooses a story, and then decides which details to report. The days of rampant sensationalism have not disappeared; moreover, the seedy transgressions of newspapermen were common enough years later for Alexander Mackendrick to film Sweet Smell of Success in 1957 or Billy Wilder to make Ace in the Hole in 1951. Wilder also directed the 1974 version of The Front Page and made it feel reflective of the times.

Out of regard for the press (if only the reviewing press), Hawks’ film opens with this foreword, but then later depicts a staggering censure of news media culture. Consider the scene where Williams’ meek (later hysterical) lady friend Mollie Malloy (Helen Mack Murphy) attempts to tell the newspapermen her side, but they refuse to listen, their stories already written. Later, when they need to pump her for information as to the whereabouts of the recently escaped Williams, she cries, “What do you want to know for? So you can write more lies to sell papers?” Their open manipulation drives her to suicide, giving them something to write about other than Williams. Or consider how Hildy wants to escape the newspaper business because of such twisted tactics. The number of times she infers that newspapermen are inhuman and says getting out of the business will allow her to become a “human being” is staggering. And yet miraculously, in the end, Hawks has somehow made it a happy ending that Hildy and Burns end up together, and Hildy has resolved to be inhuman by continuing her career as a reporter.

Out of regard for the press (if only the reviewing press), Hawks’ film opens with this foreword, but then later depicts a staggering censure of news media culture. Consider the scene where Williams’ meek (later hysterical) lady friend Mollie Malloy (Helen Mack Murphy) attempts to tell the newspapermen her side, but they refuse to listen, their stories already written. Later, when they need to pump her for information as to the whereabouts of the recently escaped Williams, she cries, “What do you want to know for? So you can write more lies to sell papers?” Their open manipulation drives her to suicide, giving them something to write about other than Williams. Or consider how Hildy wants to escape the newspaper business because of such twisted tactics. The number of times she infers that newspapermen are inhuman and says getting out of the business will allow her to become a “human being” is staggering. And yet miraculously, in the end, Hawks has somehow made it a happy ending that Hildy and Burns end up together, and Hildy has resolved to be inhuman by continuing her career as a reporter.

By switching Hildy Johnson to a woman, Hawks intended to create a diversity of sexual tension throughout the story, building an element of romance in the plot as Burns attempts to win back Hildy. But Hawks and Lederer also, perhaps unintentionally, develop a dynamic that challenges sexual politics and gender assignments of both the era and in motion pictures of time. Hildy intends to embrace her womanhood in her marriage to Baldwin by becoming a conventional housewife and mother. Except her feminist identity is ingrained into being a newspaperman, being the sole female in a male-dominated profession, and being the best among them. Hildy’s feminist identity, which she accepts in the final scenes, defies traditional gender roles of the 1940s woman. One of her colleagues remarks, “Can you picture Hildy singin’ lullabies and hanging out diapers?” Her station as a newspaperman, an independent professional and a woman, challenges myths about the sexes, and presents Hildy’s case as that of an intelligent, independent woman who finds herself in a male-dominated world. With a choice between an old-fashioned marriage and a comparatively modern career as a newspaperman, Hildy chooses the less “feminine” of the two, and in turn, renders His Girl Friday a feminist work ahead of its time in Hollywood.

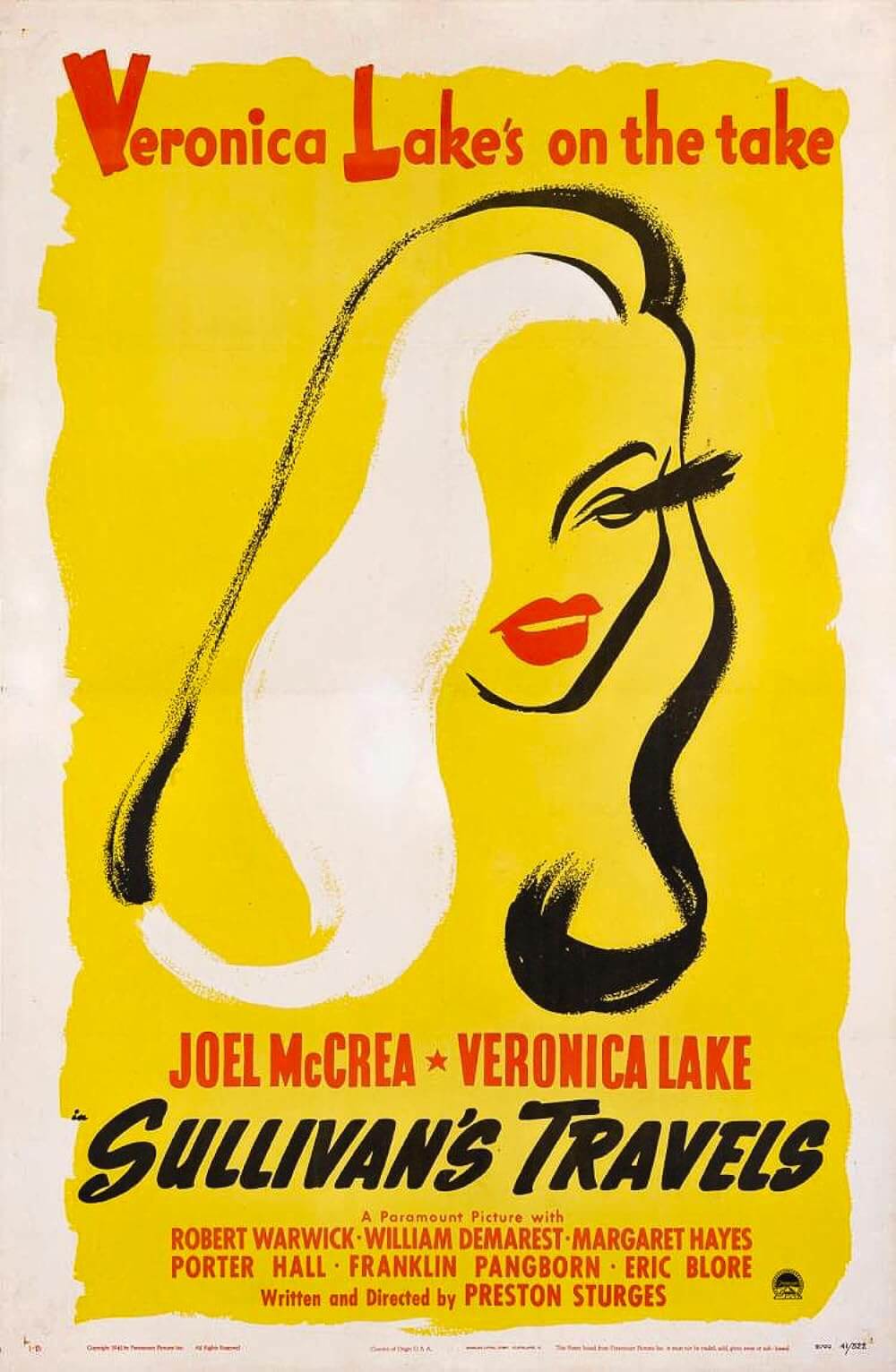

Received with almost universal critical and commercial praise, these reactions were common among Hawks’ screwball comedies, all riotous films that took cues from pioneers like Ernst Lubitsch (Trouble in Paradise, 1932) and foretold innovators like Preston Sturges (The Great McGinty, 1940). Indeed, the genre peaked in the years before and after 1940, a period that gave us The Lady Eve, My Man Godfrey, Sullivan’s Travels, and To Be or Not To Be among others, only to fade out of popularity and eventually into a distant memory in the subsequent decades, with rare emergences in modern cinema. Only Joel and Ethan Coen have channeled the style of His Girl Friday in their quirky ode The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), featuring Jennifer Jason Leigh giving a spot-on Rosalind Russell impersonation, Paul Newman as a crooked wheeler-dealer, and Tim Robbins as a dopey Bruce Baldwin type (“You know… For kids!”).

However, more than screwball comedies, Hawks explored almost every genre during his near-50-year career, completing 44 films as director and many more as producer and writer. Hawks made some of Hollywood’s great Westerns (Red River (1948) and Rio Bravo (1959)), noirish mysteries (The Big Sleep, 1946), war movies (Sergeant York, 1941), gangster pictures (Scarface, 1932), and even produced horror (The Thing from Another World, 1951). His approach was simple: “Three great scenes, no bad ones.” Strong storytelling. Straightforward presentation. An unassuming technical approach. Although many of his films transcend his definition, few fail to live up to it. Unlike Michael Curtiz (Casablanca) or Raoul Walsh (White Heat), Hawks’ craftsmanlike style also has personal signature from genre to genre in terms of thematic interests, which makes his characterization as an auteur filmmaker a simpler task. Indeed, the Cahier du Cinema proclaimed him to be the greatest American auteur. In reflection of his work, his strong female characters, and vulnerable heroes, his personal style becomes apparent, leaving Hawks’ output to constitute one of America’s finest directorial bodies of work for any Hollywood technician.

However, more than screwball comedies, Hawks explored almost every genre during his near-50-year career, completing 44 films as director and many more as producer and writer. Hawks made some of Hollywood’s great Westerns (Red River (1948) and Rio Bravo (1959)), noirish mysteries (The Big Sleep, 1946), war movies (Sergeant York, 1941), gangster pictures (Scarface, 1932), and even produced horror (The Thing from Another World, 1951). His approach was simple: “Three great scenes, no bad ones.” Strong storytelling. Straightforward presentation. An unassuming technical approach. Although many of his films transcend his definition, few fail to live up to it. Unlike Michael Curtiz (Casablanca) or Raoul Walsh (White Heat), Hawks’ craftsmanlike style also has personal signature from genre to genre in terms of thematic interests, which makes his characterization as an auteur filmmaker a simpler task. Indeed, the Cahier du Cinema proclaimed him to be the greatest American auteur. In reflection of his work, his strong female characters, and vulnerable heroes, his personal style becomes apparent, leaving Hawks’ output to constitute one of America’s finest directorial bodies of work for any Hollywood technician.

A film resting on the speed and timing of its delivery, as well as the talent of Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell, His Girl Friday remains a whimsical classic whose sheer velocity earned Hawks boasting rights over Milestone’s earlier version. Returning to the film brings, at the very least, the possibility to catch every double-edged line, but also exposes its most enduring quality by wrapping the viewer up in a breakneck back-and-forth filled with charm and some sneaky commentary. Hawks caricatures the fictional world of the newspaper business and embraces stereotypes that reach beyond their origins and into our modern consciousness. The fast-talking newspaperman, meant to be an equally disdainful and humorous notion in Hecht and MacArthur’s play, transforms into a romantic ideal from yesteryear in a way only the Golden Age of Hollywood could conceive.

Bibliography:

Bogdanovich, Peter. Who the Devil Made It. New York: Alfred A.Knopf, 1997.

Hecht, Ben; MacArthur, Charles. The Front Page. New York: Covici-Friede, 1928.

McCarthy, Todd. Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood. New York: Grove Press, 2000.

Haskell, Molly. From Reverence to Rape. Baltimore, Md.: Penguin Books, 1974.

Russell, Rosalind; Chase, Chris. Life’s a Banquet. New York: Random House, 1977.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review