The Definitives

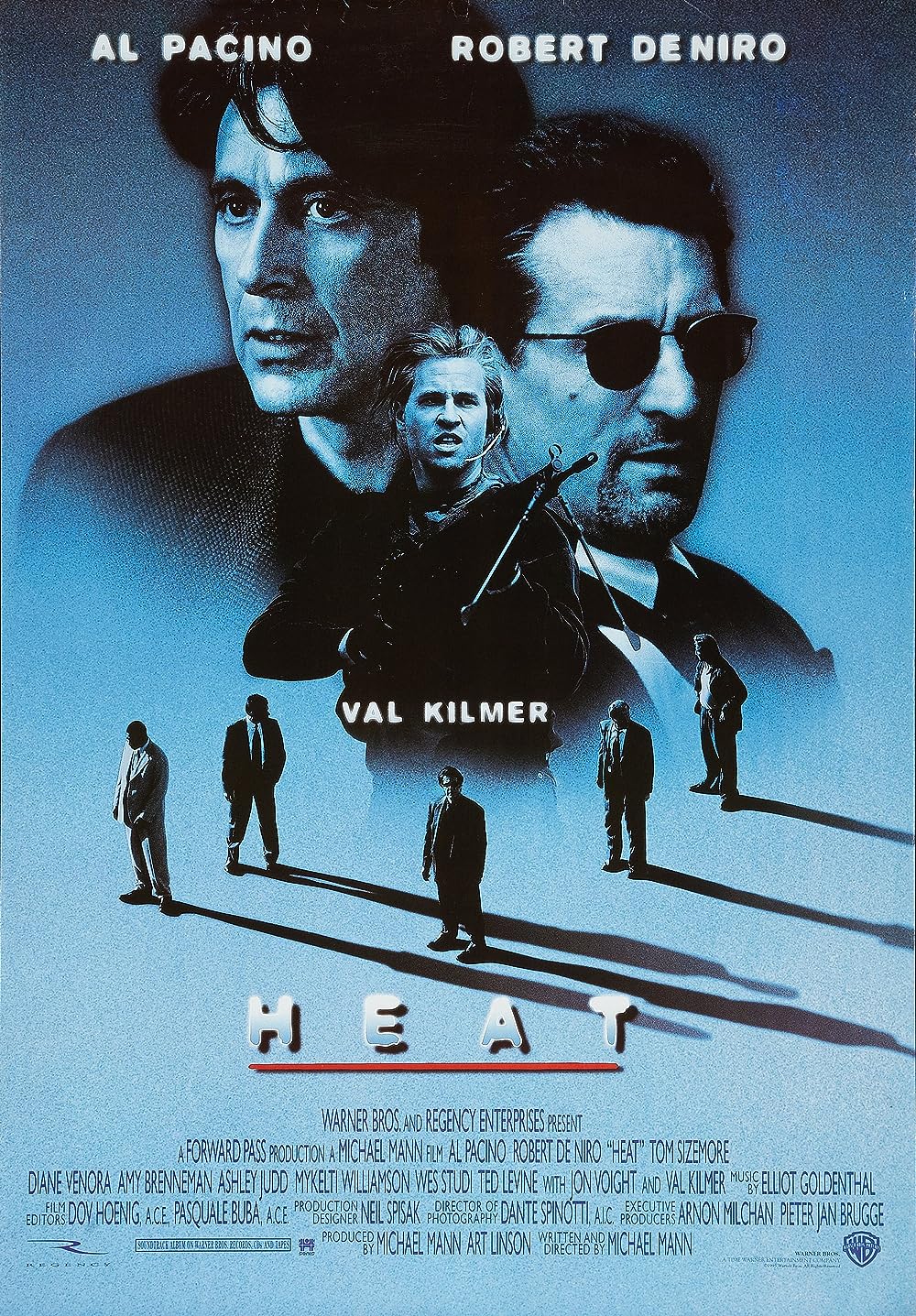

Heat (1995)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In Heat, all the meticulous authenticity and coolly portrayed characters inherent to a Michael Mann picture fulfill a crime epic of incredible scale and ambition. Over the course of twenty years, Mann developed and accumulated detail for his script, and in 1995 he set out to broaden the limitations of an otherwise formal genre structure. Lending an atypical approach to a basic “cops and robbers” scenario, Mann achieved a film less about crime genre exploits and more about the failing machismo of two uncompromising men. As a professional thief heading an expert crew and the unrelenting detective pursuing them, icons Robert De Niro and Al Pacino make their first onscreen appearance together in the film. Through their magnificent performances and Mann’s operatic script, Heat becomes a crime-infused melodrama beyond compare. More than basic genre thrills, which this film has in abundance, Mann’s moody character piece explores the inner lives of his subjects, how their work affects their relationships, and how their ongoing existential and personal dilemmas derive from their professional lives. Unique to the film is Mann’s daring balance of human tragedy and genre excitement; even while he considers weighty themes of identity and troubled masculinity, his treatment of the action operates in a hyper-real mode that grounds the film’s theatricality into a stirring, convincing drama.

Mann’s career as a feature filmmaker consists of projects infused with a single unchanging contradiction: his are films marked by their realism yet brimming with style. By definition, style is an ornamentation of reality, and this aesthetic conflict has never been ideologically resolved by Mann yet it is the balance of these components that makes many of his films great. Amid Mann’s occasional failures, the normally incongruous pairing of style and realism delivers the kind of motion picture to which the director is best attributed. After growing up in a tough Chicago neighborhood where he filmed some of the Chicago riots as a student, Mann attended the London International Film School in the mid-1960s and studied documentary film-making. His footage of the 1968 Paris riots earned him some notoriety, and after several years he broke into television by writing and producing TV movies and cop shows (such as Starsky and Hutch, Police Story, Vega$, Miami Vice, and Crime Story). Strong notices for his ABC movie-of-the-week, The Jericho Mile (1979), about prison life shot entirely within Folsom State Penitentiary, earned Mann and his severe realism attention from Hollywood. Mann’s reputation would be forever solidified by his immersive, stunningly detailed environments that are at once loaded with the capacity for narrative drama, but his work was also inhabited with a remarkable level of pure information. Mann’s authenticity is then counteracted and sometimes balanced by his visual style, which includes a rich use of colors and visual metaphors to enhance his realism with superbly melodramatic flourishes.

In 1981, Mann and friend Chuck Adamson, a former Chicago detective, teamed on the director’s first feature film, Thief, an adaptation of jewel thief John Seybold’s book (written under pseudonym Frank Hohimer) The Night Invaders. The book was enhanced by Adamson’s real-life recollections of a talented professional criminal, John Santucci. Being Mann’s own film most closely related to Heat, much of the specificity and planning shown in Thief comes from Adamson’s input; yet this is also a film of fabulous style, including synth music by Tangerine Dream, and an impressive melodrama courtesy of James Caan’s hardened crook abandoning his family life for his professional code. Mann’s style pervades over realism in Manhunter (1986), the director’s film version of the Thomas Harris novel Red Dragon, a garish serial killer yarn teeming with a visual flamboyance that distracts from the story. Later came The Last of the Mohicans (1992), based on James Fenimore Cooper’s novel and George B. Seitz’s 1936 film. The celebrated historical accuracy of this film is only matched by its high wartime drama. After Heat, Mann made his extraordinary The Insider (1999), an exceptionally acted and truth-telling account of a 60 Minutes producer’s fight to air a controversial segment on a Big Tobacco whistleblower. More contradictions of realism and style followed, including Ali (2001), Collateral (2004), Miami Vice (2006), and Public Enemies (2009)—the last of which, set in the 1930s, found another determined cop going after career criminal John Dillinger. Although, like Public Enemies, many of these post-Heat films boast excellent performances and writing, it is often Mann’s application or over-application of style that makes or breaks the end result.

In 1981, Mann and friend Chuck Adamson, a former Chicago detective, teamed on the director’s first feature film, Thief, an adaptation of jewel thief John Seybold’s book (written under pseudonym Frank Hohimer) The Night Invaders. The book was enhanced by Adamson’s real-life recollections of a talented professional criminal, John Santucci. Being Mann’s own film most closely related to Heat, much of the specificity and planning shown in Thief comes from Adamson’s input; yet this is also a film of fabulous style, including synth music by Tangerine Dream, and an impressive melodrama courtesy of James Caan’s hardened crook abandoning his family life for his professional code. Mann’s style pervades over realism in Manhunter (1986), the director’s film version of the Thomas Harris novel Red Dragon, a garish serial killer yarn teeming with a visual flamboyance that distracts from the story. Later came The Last of the Mohicans (1992), based on James Fenimore Cooper’s novel and George B. Seitz’s 1936 film. The celebrated historical accuracy of this film is only matched by its high wartime drama. After Heat, Mann made his extraordinary The Insider (1999), an exceptionally acted and truth-telling account of a 60 Minutes producer’s fight to air a controversial segment on a Big Tobacco whistleblower. More contradictions of realism and style followed, including Ali (2001), Collateral (2004), Miami Vice (2006), and Public Enemies (2009)—the last of which, set in the 1930s, found another determined cop going after career criminal John Dillinger. Although, like Public Enemies, many of these post-Heat films boast excellent performances and writing, it is often Mann’s application or over-application of style that makes or breaks the end result.

Only after Mann earned vast acclaim and box-office success for The Last of the Mohicans was the theatrical feature Heat possible. The basis for Mann’s screenplay, written years earlier, was a true story relayed to him by Adamson in the 1970s. In his Chicago years, Adamson tracked and, in 1964, killed a professional thief and ex-Alcatraz resident named Neil McCauley whom Adamson greatly admired. While hunting McCauley, Adamson met him for coffee and they shared a conversation. The cop found the crook to be as intelligent and as resolute as himself, and he thought that perhaps in another life they might have been friends. Still, when he eventually confronted McCauley at the scene of an armored car robbery, Adamson shot and killed his opponent during a gunfight. Fascinated by the notion of a cop who admires a thief and the duality of that admiration, Mann wrote a script based on Adamson’s story and first produced it as a TV movie in 1989 called L.A. Takedown, although the outcome contained few of Heat’s many dramatic subplots and almost none of its precision filmmaking. Later, Mann showed the expanded script to producer Art Linson (The Untouchables), and they agreed to develop the material into a feature. Linson pursued his frequent collaborator Robert De Niro to star, while Mann sought Al Pacino. Both powerhouse actors at the height of their respective careers, when De Niro and Pacino signed on the film was greenlit with a budget of $60 million, a number that was more than tripled at the box-office.

The first shots of Heat show Neil McCauley (De Niro) stealing an ambulance from a hospital on his way to his next score. Dark, clean-cut, and composed, every step McCauley takes is a confident one, rigidly adhered to his strict professional code. Other members of McCauley’s crew—Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer), Michael Cherrito (Tom Sizemore), and Trejo (Danny Trejo)—assemble along with hired-hand outsider Waingro (Kevin Gage) at the designated time and place for an armored car robbery. In a gripping sequence, they make off with their target, $1.6 million in bearer bonds, but Waingro has botched the smoothly running score by killing one of the guards. As a result, the other two guards must die as witnesses. Unbeknownst to McCauley and his fence, Nate (John Voight), the bonds belonged to money launderer Roger Van Zant (William Fichtner). Since the bonds are insured, Nate suggests selling them back to Van Zant for a lesser price to scam the insurance company; Van Zant agrees but plans a double-cross and tries to have McCauley killed at the eventual meet. In the interim, McCauley’s crew tries to rid themselves of Waingro, but he escapes and continues a series of prostitute killings. With the unsettled scores of Van Zant and Waingro hanging over him, the loner McCauley meets a young woman, Eady (Amy Brenneman), and suddenly his emotions test his professional code, which states “Don’t let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.” Nevertheless, as McCauley grows more and more attached to Eady, his plans for a daring bank heist that will be his final job are made all the more desperate.

The first shots of Heat show Neil McCauley (De Niro) stealing an ambulance from a hospital on his way to his next score. Dark, clean-cut, and composed, every step McCauley takes is a confident one, rigidly adhered to his strict professional code. Other members of McCauley’s crew—Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer), Michael Cherrito (Tom Sizemore), and Trejo (Danny Trejo)—assemble along with hired-hand outsider Waingro (Kevin Gage) at the designated time and place for an armored car robbery. In a gripping sequence, they make off with their target, $1.6 million in bearer bonds, but Waingro has botched the smoothly running score by killing one of the guards. As a result, the other two guards must die as witnesses. Unbeknownst to McCauley and his fence, Nate (John Voight), the bonds belonged to money launderer Roger Van Zant (William Fichtner). Since the bonds are insured, Nate suggests selling them back to Van Zant for a lesser price to scam the insurance company; Van Zant agrees but plans a double-cross and tries to have McCauley killed at the eventual meet. In the interim, McCauley’s crew tries to rid themselves of Waingro, but he escapes and continues a series of prostitute killings. With the unsettled scores of Van Zant and Waingro hanging over him, the loner McCauley meets a young woman, Eady (Amy Brenneman), and suddenly his emotions test his professional code, which states “Don’t let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.” Nevertheless, as McCauley grows more and more attached to Eady, his plans for a daring bank heist that will be his final job are made all the more desperate.

Throughout the picture, Mann intercuts McCauley’s scenes with those of Lieutenant Vincent Hanna (Pacino) of the LAPD Robbery-Homicide Division. Hanna, a tenacious cop on his third marriage, this time to neglected wife Justine (Diane Venora), arrives on the scene of McCauley’s armored car robbery in Heat’s opening and immediately recognizes the skill needed for such crime. Persistent detective work puts him onto the scent of McCauley’s ever-cautious crew, and a cat-and-mouse game persists as Hanna’s regard for McCauley’s sharp instincts is matched only by his desire to catch him. At home, Justine announces her frustration by having an affair, while Hanna’s teenaged stepdaughter Lauren (Natalie Portman) shows signs of depression over her inattentive biological father. Unable to catch his prey and frustrated with his crumbling home life, Hanna engages McCauley directly and asks him to sit down for a cup of coffee. The two men talk and relate to one another: Hanna laments how his devotion to the job has made his home life miserable; McCauley describes how his relationship with his woman is fleeting because his self-imposed code means he must always be on the lookout, ready to leave her at a moment’s notice. Despite sharing mutual feelings about their personal and professional lives, and their mutual admiration for one another, both men maintain that should they meet again at the scene of McCauley’s next crime, neither will hesitate to open fire.

At this point in Heat, the viewer must pause to appreciate how Mann has not exploited what must have been forecast as a landmark scene in motion pictures, as well as the perfect casting of De Niro and Pacino. Mann captures a moment where both actors are at their height. Neither actor appears too young or old for their role as an experienced professional. Their reputations are both at their zenith in 1995, not yet soured by De Niro’s eventual paycheck comedies or Pacino’s presence in a dozen cheap cop movies (nor their disgraceful appearance together in Righteous Kill). They’re cast into crime genre roles similar to those that made them living legends. In The Godfather Part II (1974), Pacino played Michael Corleone and in flashbacks De Niro played the younger version of Michael’s father Vito, but they never shared a scene together. Pacino had played smart cops in Serpico (1973), Sea of Love (1989), and Cruising (1980); De Niro the criminal had been a cinema standard from Mean Streets (1973) to The Untouchables (1987) to Goodfellas (1990). Here, Mann casts them into characters that channel our cinematic memory and in doing so makes perfect use of their screen celebrity and talent, but he never abuses their presence. For their central meeting at the coffee shop, Mann resists shooting them together to such a self-conscious degree that some audiences wondered if the actors even shot the scene together. Although behind-the-scenes photographs and footage show Mann working closely with his two performers for the scene, he avoids placing them in the frame together in any way until Heat’s final shot. Instead of panning to his audience, Mann caters to the integrity of the filmmaking and presents a small but crucial coffee shop scene as the highpoint in the film.

At this point in Heat, the viewer must pause to appreciate how Mann has not exploited what must have been forecast as a landmark scene in motion pictures, as well as the perfect casting of De Niro and Pacino. Mann captures a moment where both actors are at their height. Neither actor appears too young or old for their role as an experienced professional. Their reputations are both at their zenith in 1995, not yet soured by De Niro’s eventual paycheck comedies or Pacino’s presence in a dozen cheap cop movies (nor their disgraceful appearance together in Righteous Kill). They’re cast into crime genre roles similar to those that made them living legends. In The Godfather Part II (1974), Pacino played Michael Corleone and in flashbacks De Niro played the younger version of Michael’s father Vito, but they never shared a scene together. Pacino had played smart cops in Serpico (1973), Sea of Love (1989), and Cruising (1980); De Niro the criminal had been a cinema standard from Mean Streets (1973) to The Untouchables (1987) to Goodfellas (1990). Here, Mann casts them into characters that channel our cinematic memory and in doing so makes perfect use of their screen celebrity and talent, but he never abuses their presence. For their central meeting at the coffee shop, Mann resists shooting them together to such a self-conscious degree that some audiences wondered if the actors even shot the scene together. Although behind-the-scenes photographs and footage show Mann working closely with his two performers for the scene, he avoids placing them in the frame together in any way until Heat’s final shot. Instead of panning to his audience, Mann caters to the integrity of the filmmaking and presents a small but crucial coffee shop scene as the highpoint in the film.

Mann’s integrity is also evident in the bank robbery which occurs after the coffee shop meet. Whereas another heist yarn might designate such a bold crime as the climax of the story, Mann places it at the center and follows the bravado sequence with a lengthy aftermath rooted in the dramatic fates of his characters. The focus in Heat is not the fantastical crimes but the lives of the people surrounding them. McCauley’s crew enters the bank in broad daylight and performs the bank heist with practiced efficiency. Upon exiting to the getaway car, McCauley, Shiherlis, and Cherrito are met by Hanna and the virtual army of cops who were tipped off by Van Zant and Waingro. A violent standoff in the city streets erupts between cops and robbers. Cherrito dies, Shiherlis is injured, and McCauley barely escapes, while several cops lose their lives. Desperate to track down McCauley before he can leave town, Hanna finds that McCauley is tying up loose ends, among them Van Zant. With Eady, who has discovered that her lover is a professional thief, McCauley promises to reform if they run away together; hesitant but also lonely, she agrees. Meanwhile, Hanna has lost the trail, distracted by Lauren, who has attempted suicide and in that brought he and Justine closer. McCauley and Eady are all but “home free” to the airport when his compulsive drives send him on a last-minute undertaking to finally eliminate Waingro. After the deed is done, he returns to Eady but sees Hanna, who was tipped off about Waingro’s location, approaching. McCauley does as he promised and turns away from Eady, who looks on with fragile confusion and devastation over her abandonment. After a short chase across an airport tarmac, Hanna too carries out his promise and shoots McCauley down.

Heat remains an enduring classic for a number of reasons, not the least of which are De Niro, Pacino, and a number of strong supporting performances. The actors benefit from Mann’s script, as he fleshes out nearly every character in this crime epic, ingraining a level of seriousness and dramatic heft to heighten not only his film’s realism but its emotional impact. This quality sets the film apart from prototypical “cops and robbers” stories. Not one character feels one-dimensional, unnecessary, or unauthentic within the story. Every subplot adds to the complexity of his characters and the film’s dramatic gravitas. Lauren’s shocking suicide attempt is one example among many. Consider also Shiherlis’ wife Charlene (Ashley Judd) and her affair with scummy criminal Alan Marciano (Hank Azaria), a reluctant snitch who gives Charlene up to Hanna. Charlene, who must contend with her gambling addict husband and the risks he takes as a professional thief, while also trying to ensure a future for their young child, resolves to help Hanna capture her husband. But Shiherlis doesn’t follow McCauley’s strict professional code; he says he will forever remain devoted to Charlene, but his fluidity in this respect allows him to eventually evade capture by abandoning his family to escape. Another subplot involves Breeden (Dennis Haysbert), an ex-con just out of Folsom and struggling to reform for his loving wife Lillian (Kim Staunton) in a shoddy-but-legitimate diner post. When McCauley needs to replace his getaway driver on the morning of the bank robbery, he spots Breeden flipping burgers and asks him to join. Breeden agrees and the decision gets him killed. In the aftermath of the robbery, a news report announces Breeden’s death. Mann cuts to Lillian for a wordless expression of utter heartbreak.

Heat remains an enduring classic for a number of reasons, not the least of which are De Niro, Pacino, and a number of strong supporting performances. The actors benefit from Mann’s script, as he fleshes out nearly every character in this crime epic, ingraining a level of seriousness and dramatic heft to heighten not only his film’s realism but its emotional impact. This quality sets the film apart from prototypical “cops and robbers” stories. Not one character feels one-dimensional, unnecessary, or unauthentic within the story. Every subplot adds to the complexity of his characters and the film’s dramatic gravitas. Lauren’s shocking suicide attempt is one example among many. Consider also Shiherlis’ wife Charlene (Ashley Judd) and her affair with scummy criminal Alan Marciano (Hank Azaria), a reluctant snitch who gives Charlene up to Hanna. Charlene, who must contend with her gambling addict husband and the risks he takes as a professional thief, while also trying to ensure a future for their young child, resolves to help Hanna capture her husband. But Shiherlis doesn’t follow McCauley’s strict professional code; he says he will forever remain devoted to Charlene, but his fluidity in this respect allows him to eventually evade capture by abandoning his family to escape. Another subplot involves Breeden (Dennis Haysbert), an ex-con just out of Folsom and struggling to reform for his loving wife Lillian (Kim Staunton) in a shoddy-but-legitimate diner post. When McCauley needs to replace his getaway driver on the morning of the bank robbery, he spots Breeden flipping burgers and asks him to join. Breeden agrees and the decision gets him killed. In the aftermath of the robbery, a news report announces Breeden’s death. Mann cuts to Lillian for a wordless expression of utter heartbreak.

Mann’s affinity for tragedy throughout Heat might reach too far if he did not counterbalance his melodrama with astounding realism and subtle style. The director demonstrates efficiency, self-control, and simplicity worthy of comparison to Jean-Pierre Melville’s similarly themed Le cercle rouge (1970), whose penchant for cool style and scrupulous details were clearly an influence on Mann. Note the Melvillian stroke in Mann’s robbers and how they dress; McCauley’s crew does not look like crooks or even very masculine. They look stylish, if not chic in their designer suits; clean cut and organized. As McCauley notes, “Do you see me doin’ thrill-seeker liquor store hold-ups with a ‘Born To Lose’ tattoo on my chest?” Of course not. McCauley’s crew is professional, and therefore not subject to the stupid mistakes made by robbers in Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956) or Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992). Mann has elevated these professionals with melodrama and tragedy. Another clear influence is Raoul Walsh’s gangster classic White Heat (1949), an equally tragic tale starring James Cagney as a criminal made insane by his inner conflicts and his chosen line of work. Mann’s film is distinct in that he resolves to conceal his drama within the reality of his setting, the sprawling concrete wasteland of Los Angeles. Shooting at 85 locations around LA, Mann depicts a mythic asphalt jungle where the muted street scenery provides a contrast to his dramatic characters. Cinematographer Dante Spinotti’s lensing is blue-hued and dark, conveying characters that appear pale in their surroundings, yet their lives are filled with hugely dramatic events. The look of Heat is textured and gloriously cinematic, just as much as Mann’s choice of music that alternates between classic orchestral strings to the booming sounds of Moby’s “New Dawn Fades”. Always, the director is juxtaposing realism and style.

Every genuine detail that makes Heat thrilling is offset by touches of reality. The bank robbery sequence, shot with an economy of precise images and sounds to inspire later filmmakers such as Christopher Nolan (in The Dark Knight and Inception) and Ben Affleck (in The Town), is the prime example. McCauley’s crew exits the bank to find Hanna’s posse, and a Western-style showdown ensues: the sheriff and his deputies versus the masked hoods who have terrorized the townsfolk. The reverberation of automatic weapons fire against the surrounding concrete sounds unlike any gunfire in cinema before—a sound Mann and his sound department went to great lengths to perfect. As much as we admire De Niro as McCauley and almost want him to kill Hanna and escape in the end, Mann reminds us that McCauley’s teammates are still “bad guys”. During the bank heist shootout, bystanders are shot and Mann’s camera, always in the moment, pays little attention. But when Cherrito picks up a little girl as a human shield, the frame goes into slow-motion as Hanna lines up a shot into Cherrito’s forehead. The presence of the little girl has removed all sense of “fun” from the robbery’s cinematic thrill. All of Mann’s influential meticulousness does not amount to a glorification of violence or criminality like many films in the crime genre; rather, they are a dramatic amplification of reality that leaves Heat feeling like real-life drama yet not unsympathetic toward its characters. In this sense, Mann’s otherwise conflicting proclivities toward realism and tragedy become a perfect marriage of opposites.

Every genuine detail that makes Heat thrilling is offset by touches of reality. The bank robbery sequence, shot with an economy of precise images and sounds to inspire later filmmakers such as Christopher Nolan (in The Dark Knight and Inception) and Ben Affleck (in The Town), is the prime example. McCauley’s crew exits the bank to find Hanna’s posse, and a Western-style showdown ensues: the sheriff and his deputies versus the masked hoods who have terrorized the townsfolk. The reverberation of automatic weapons fire against the surrounding concrete sounds unlike any gunfire in cinema before—a sound Mann and his sound department went to great lengths to perfect. As much as we admire De Niro as McCauley and almost want him to kill Hanna and escape in the end, Mann reminds us that McCauley’s teammates are still “bad guys”. During the bank heist shootout, bystanders are shot and Mann’s camera, always in the moment, pays little attention. But when Cherrito picks up a little girl as a human shield, the frame goes into slow-motion as Hanna lines up a shot into Cherrito’s forehead. The presence of the little girl has removed all sense of “fun” from the robbery’s cinematic thrill. All of Mann’s influential meticulousness does not amount to a glorification of violence or criminality like many films in the crime genre; rather, they are a dramatic amplification of reality that leaves Heat feeling like real-life drama yet not unsympathetic toward its characters. In this sense, Mann’s otherwise conflicting proclivities toward realism and tragedy become a perfect marriage of opposites.

The film also establishes disparate sexual politics between men and women, between dedicated professional men uncomfortable with themselves and the women who wait for them to return home. McCauley and Hanna excel at their professions but struggle with their personal lives; they desire a better home life, but their work consumes them. Women characters from Justine to Eady to Charlene represent the “real world” outside of taking scores or tracking criminals; their presence and the emotional veracity that Mann impels into these relationships make both McCauley and Hanna seem insane for taking the risks they do. As a result, McCauley and Hanna both have anxieties about women and work, because for them it’s impossible to find a balance between the two. Hanna feels guilt over always having to rush off to investigate another crime. Watch the way he catches himself after coming home late one night and ruining Justine’s meal: He begins “I’ve got three dead bodies on a sidewalk off Venice boulevard, Justine.” And then he realizes he has no reason to take it out on Justine, trailing off “I’m sorry if the goddamn… chicken got… overcooked.” Later, Hanna looks on with guilt when Justine tells him “You don’t live with me, you live among the remains of dead people. You sift through the detritus, you read the terrain, you search for signs of passing, for the scent of your prey, and then you hunt them down. That’s the only thing you’re committed to. The rest is the mess you leave as you pass through.” McCauley, meanwhile, is temped away from his self-imposed rules about no attachments, as attachments are inevitable in life. McCauley doesn’t help his own cause by being a romantic, tender even as he talks to Eady about how the LA lights look like iridescent algae in Figi, how he’s never been there, and how he’s going there “someday”. He claims “I’m alone, I am not lonely” but both Eady and the audience can see that’s not true.

The duality of cop and robber in Heat drives the drama and the action. McCauley and Hanna are not the black and white opposites usually found in the cops and robbers genre; they are two men living inside the gray zone that is their lives, which are ruined by their addiction to the hunting and thieving that represents their own elevated states of mind. Because they share this, they can relate to one another on a level no companion ever could. Their relationship with one another—however thin and barely connected in any traditional, meaningful way—is more important to each man than their respective personal relationships. Hanna’s story is tragic but ultimately gallant since in the end he gets his man. McCauley’s narrative arc is more tragic. He lives by his self-appointed regimentation, his notion that someone in his line of work should not become attached. McCauley’s own discipline makes anything outside of his own rules impossible and eventually fatal. He would have never gone after Waingro, and thus had his fateful run-in with Hanna, had his love for Eady not made him feel somehow invincible. He creates his own fate by going against his own axiom, which is tragic; but it’s also tragic that his rules have done this to him. Hanna admires McCauley but does not romanticize him by, say, trying to preserve McCauley’s life by saving McCauley from himself—by wounding him in the final shootout and sending him back to prison, for example. Hanna kills McCauley without hesitation, perhaps knowing McCauley would prefer to die. Because Hanna admires his opponent to this degree, the poignancy of Heat’s last shot is overwhelming.

The duality of cop and robber in Heat drives the drama and the action. McCauley and Hanna are not the black and white opposites usually found in the cops and robbers genre; they are two men living inside the gray zone that is their lives, which are ruined by their addiction to the hunting and thieving that represents their own elevated states of mind. Because they share this, they can relate to one another on a level no companion ever could. Their relationship with one another—however thin and barely connected in any traditional, meaningful way—is more important to each man than their respective personal relationships. Hanna’s story is tragic but ultimately gallant since in the end he gets his man. McCauley’s narrative arc is more tragic. He lives by his self-appointed regimentation, his notion that someone in his line of work should not become attached. McCauley’s own discipline makes anything outside of his own rules impossible and eventually fatal. He would have never gone after Waingro, and thus had his fateful run-in with Hanna, had his love for Eady not made him feel somehow invincible. He creates his own fate by going against his own axiom, which is tragic; but it’s also tragic that his rules have done this to him. Hanna admires McCauley but does not romanticize him by, say, trying to preserve McCauley’s life by saving McCauley from himself—by wounding him in the final shootout and sending him back to prison, for example. Hanna kills McCauley without hesitation, perhaps knowing McCauley would prefer to die. Because Hanna admires his opponent to this degree, the poignancy of Heat’s last shot is overwhelming.

To label the film merely a crime story, melodrama, heist movie, policier in the French definition, or even a thriller limits the film’s true reaches and downplays its epic stature. Perhaps it’s all of the above, which makes the film something unique and therefore special. Apparent from the outset is Mann’s vast dramatic objectives and his skill behind the camera, but is there a message to his film, or does Heat simply resolve to be another entry in the genre featuring Al Pacino and Robert De Niro as cop and crook? It is much more than that, but defining a picture as complex as this remains a challenge, yet complexity is also sometimes a determining characteristic of great cinema. Much like the characters and formal approach of Heat, both represented with curious incongruities, the film is not easy to dissect or define. There are contradictions abound, such as Mann’s use of both realism and style, or the raw thrill of his robbery sequences versus the emotional significance of the story. If there is a thematic lesson, it may be that it’s dangerous if not impossible to be alone, but to be truly successful, one must be alone, which itself is a paradox. That Mann finds a balance between our concern for his characters’ personal lives and the outcome of their stunningly arranged crimes speaks to the skill of this filmmaker’s finest picture, a sweeping, deeply moving saga.

Bibliography:

James, Nick. Heat (BFI Modern Classics). London: British Film Institute, 2002.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review