The Definitives

Harakiri (1963)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

(This essay was originally published on September 3, 2009. It has been significantly edited and expanded.)

Harakiri opens with a shot of ancestral samurai armor on display in a dramatic, dark, ceremonial room. Accented by smoke and backlighting that illuminates its mythical authority, the armor appears seated on a stage, its helmet and faceplate empty, its function decorative and symbolic. Masaki Kobayashi’s provocative 1962 film uses the armor as a central image of a hollow ideology, devoid of humanity, that drives systems of authority and social control. In one of the film’s final moments, an outraged samurai uses the last of his strength to pull the armor to the ground. Harakiri is a similar act of defiance characteristic of Kobayashi’s rebellious presence in Japan’s thriving postwar cinema. The filmmaker presents criticisms of authoritarian powers through jidai-geki, or period pieces, which veil his censures of contemporary officialdom behind their historical setting. But his message stands as a pronounced anti-establishment film, its raw moments of symbolic violence balanced with a cutting formal austerity that conveys tragic humanist and social implications. Condemning his country’s lingering ties to its militaristic past and corruptible sense of honor, Kobayashi’s tale of a feudal clan fraught with hypocrisy and the samurai who plans to expose them challenged his Japanese audience to look into their history for modern parallels. The film’s message resonates with the sharpest clarity of purpose of any film in Kobayashi’s career, and it emblematizes his need to defy authority.

Kobayashi’s rebellious tendencies began at an early age. He admitted to historian Linda Hoaglund in a 1994 interview, “All of my pictures, from a certain point on, are concerned with resisting entrenched power… I suppose I’ve always challenged authority.”After graduating from Tokyo’s Waseda University, where he studied art history, Kobayashi became an assistant director for the Shochiku Ofuna film studio in 1941. Shortly after that, he found himself drafted into the Japanese Imperial Army, where, being a pacifist, he refused promotion into the elitist command class. Though he could not protest the war openly, rejecting an officer’s position placed him alongside grunt soldiers and saved him from joining the hierarchical ranks of military leaders who caused the Pacific War, which Kobayashi believed was a senseless conflict. Surviving the war, he returned to filmmaking and began directing pictures in the 1950s. Even amid his earlier films, such as The Thick-Walled Room from 1953, Kobayashi’s rebel persona could not be denied. Based on the diaries of war criminals, the film was censored by the studio until audiences were “ready” for outright confrontational sentiments. Over the next several years, Kobayashi’s films would tell stories about individuals standing up against hypocrisies, despots, and crooked administrations.

Kobayashi believed Harakiri was his “most weighty, densest film,” according to Steven Prince’s biography. The film was adapted from Yasuhiko Takiguchi’s novel by screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto, a longtime collaborator with Akira Kurosawa on landmark pictures such as Rashomon (1950), Ikiru (1952), Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958), and The Bad Sleep Well (1960). For Kurosawa, Hashimoto wrote films that often portrayed Japan’s history through individuals who clash with larger societal forces. Together, they enhanced the samurai genre from dutiful and honor-bound soldiers to more nuanced characters who can be deceptive, predatory, and selfish. Hashimoto shared Kurosawa’s interest in capturing an accurate medieval history onscreen, yet they also portrayed samurai as individuals and not always as militaristic adherents to the samurai code—the so-called way of the warrior known as bushido, which the Japanese government co-opted in the mid-twentieth century to mobilize war efforts. In the postwar era, Japanese viewers could identify with masterless samurai known as ronin because their sense of loss and defeat in the subsequent Occupation reflected the ronin’s existential crisis. Hashimoto’s most critical instincts that questioned establishments and undermined authorities in favor of a humanist argument naturally aligned with Kobayashi’s tendencies toward rebellion. Their collaboration on Harakiri targeted the dogmatic logic of feudal lords; more decisively, the film accuses the samurai bushido code of humanist deficiencies, enough to describe the final product as an anti-samurai film. Kobayashi and Hashimoto would collaborate as director and writer again in 1967 on the similarly themed Samurai Rebellion (1967).

Takiguchi’s novel appealed to Hashimoto, given his long-held interest in harakiri, better known as seppuku, the Japanese ritual performed by samurai to atone or restore honor when they caused an offense or disgraced their masters. The ceremony involves the samurai using a short sword to slash open his belly and release his entrails in a symbolic gesture of honesty—Prince equates this to “the Western notion of ‘from the heart.’” Maintaining composure during this unthinkably painful process demonstrated a samurai’s honor and absolved him of his disgrace. Once he cut the belly, a second who assists the samurai would end the ritual by beheading him. Hashimoto’s script takes place in 1630 in Edo, the period when the bushido code was written and instilled an ideology and class structure that Japanese culture idealized. At this time of relative peace in Japan, unneeded samurai became masterless ronin, mainly because the militarized Tokugawa government had removed the powers of many daimyos who may have been a threat to the dynasty. As a result, their samurai became unemployed and wandered about, seeking work in another master’s army. In other cases, they resorted to criminality to survive. The act of harakiri provided an honorable outlet to ronin who wished to end their troubles. However, Hashimoto’s script suggests that desperate warriors might arrive at flourishing clan houses and ask to end their lives by committing seppuku, hoping the clan will offer them charity or a job to avoid the spectacle of death. Recognizing that clever ronin have been exploiting them, the heads of the Iyi clan resolve to enforce the honorable practice and pressure the former warriors into committing seppuku.

Takiguchi’s novel appealed to Hashimoto, given his long-held interest in harakiri, better known as seppuku, the Japanese ritual performed by samurai to atone or restore honor when they caused an offense or disgraced their masters. The ceremony involves the samurai using a short sword to slash open his belly and release his entrails in a symbolic gesture of honesty—Prince equates this to “the Western notion of ‘from the heart.’” Maintaining composure during this unthinkably painful process demonstrated a samurai’s honor and absolved him of his disgrace. Once he cut the belly, a second who assists the samurai would end the ritual by beheading him. Hashimoto’s script takes place in 1630 in Edo, the period when the bushido code was written and instilled an ideology and class structure that Japanese culture idealized. At this time of relative peace in Japan, unneeded samurai became masterless ronin, mainly because the militarized Tokugawa government had removed the powers of many daimyos who may have been a threat to the dynasty. As a result, their samurai became unemployed and wandered about, seeking work in another master’s army. In other cases, they resorted to criminality to survive. The act of harakiri provided an honorable outlet to ronin who wished to end their troubles. However, Hashimoto’s script suggests that desperate warriors might arrive at flourishing clan houses and ask to end their lives by committing seppuku, hoping the clan will offer them charity or a job to avoid the spectacle of death. Recognizing that clever ronin have been exploiting them, the heads of the Iyi clan resolve to enforce the honorable practice and pressure the former warriors into committing seppuku.

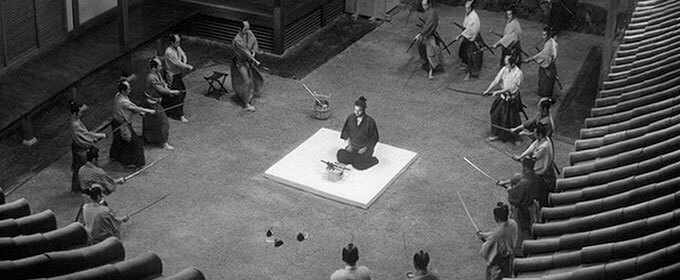

For Kobayashi, the Iyi clan represents a soulless entity that seeks to avoid extortion by warping samurai honor into a torturous punishment. The director and screenwriter structure Harakiri to gradually unveil the extent of the Iyi clan’s shameful crimes. Then, they cleverly shift focus to expose holes in bushido that prevent the characters from making just decisions. The film opens with the Iyi clan’s emblematic samurai armor, which signifies the stability of the institution and the nobility of samurai honor. The clan’s journal reads that on May 13, 1630, no official business is worth noting, suggesting that the events to follow throughout the film have been erased from House of Iyi’s records, foreshadowing that, at the film’s end, the clan remains in power. Furthermore, the date indicates that the Tokugawa shogunate’s feudal regime had just begun its reign over Japan with a military government that lasted from 1603 to 1868. In other words, the system of power shown in the film will remain for a long time after the depicted events. Appearing at the Iyi temple gate, a down-and-out masterless samurai asks for an audience so that he might commit harakiri in their square. Bearded and weary-eyed, Hanshiro Tsugumo (Tatsuya Nakadai) says he lost his master some years earlier and, having failed to find employment under another master, he wishes to die honorably.

Lord Kageyu Saito (Rentaro Mikuni) listens to Tsugumo’s request and agrees to allow him a death worthy of a samurai, wholly unaware that the ronin intends to unmask the clan and reveal its failure to conduct themselves according to the bushido code. However, before that happens, Saito shares a story about the similar case of Motome Chijiiwa (Akira Ishihama), another ronin who came to their gate asking to commit harakiri. Before Chijiiwa’s arrival, rumors spread throughout Edo of a ronin who arrived at a temple’s gates asking if he might end his life in the courtyard. The daimyo was so impressed with the samurai’s resolve that he hired him instead. All over the land, desperate ronin began appealing to their local clans in this manner, hoping to be hired as retainers; meanwhile, none of them had any intention of committing harakiri and often required a small payoff before they would leave. The Iyi clan realized Chijiiwa had the same dishonorable intentions, and to stop future ronin from pestering their temple, they decided to make an example out of him. Kobayashi tells Saito’s story in flashback, showing the result in horrible detail. Much of Harakiri unfolds in the increasing suspense from Tsugumo’s presence in the square, and how Saito attempts to weed out his true intentions. At the same time, each new piece of information shared is another component of Tsugumo’s elaborate plan to expose the Iyi clan’s dishonor.

Further explaining Chijiiwa’s fate, Saito tells Tsugumo how the clan discovered that Chijiiwa’s swords, said to be symbolic of a samurai’s soul, had been sold off and replaced by bamboo blades. They force Chijiiwa to carry out the seppuku ritual anyway, despite his pleas for a two-day respite, and refuse to let him deviate from their clan’s strict adherence to samurai honor. With no alternative, the fearful Chijiiwa thrusts the dull bamboo blades into his abdomen over and over to penetrate the skin; he then leans onto the blade to pierce deeper, releasing guttural sounds through his pain. The moment is difficult to watch and seems to go on forever, intentionally placing the viewer in Chijiiwa’s subjectivity. The scene also cuts away to Saito and the cruel swordsmen who stand guard with smug expressions on their faces, forcing him to continue. Cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima tilts the widescreen frame just enough to show the moment in its off-kilter horror. In a final moment of agony, Chijiiwa bites off his tongue to bleed to death and avoid any more torture under the sneering glares of the clan. And yet, upon hearing about Chijiiwa’s fate, Tsugumo assures Saito he has every intention of willingly committing harakiri, that his blades are indeed true, and he will not falter. Tsugumo’s composed reaction throughout this story becomes all the more impressive and haunting once the film reveals his family ties to Chijiiwa.

Further explaining Chijiiwa’s fate, Saito tells Tsugumo how the clan discovered that Chijiiwa’s swords, said to be symbolic of a samurai’s soul, had been sold off and replaced by bamboo blades. They force Chijiiwa to carry out the seppuku ritual anyway, despite his pleas for a two-day respite, and refuse to let him deviate from their clan’s strict adherence to samurai honor. With no alternative, the fearful Chijiiwa thrusts the dull bamboo blades into his abdomen over and over to penetrate the skin; he then leans onto the blade to pierce deeper, releasing guttural sounds through his pain. The moment is difficult to watch and seems to go on forever, intentionally placing the viewer in Chijiiwa’s subjectivity. The scene also cuts away to Saito and the cruel swordsmen who stand guard with smug expressions on their faces, forcing him to continue. Cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima tilts the widescreen frame just enough to show the moment in its off-kilter horror. In a final moment of agony, Chijiiwa bites off his tongue to bleed to death and avoid any more torture under the sneering glares of the clan. And yet, upon hearing about Chijiiwa’s fate, Tsugumo assures Saito he has every intention of willingly committing harakiri, that his blades are indeed true, and he will not falter. Tsugumo’s composed reaction throughout this story becomes all the more impressive and haunting once the film reveals his family ties to Chijiiwa.

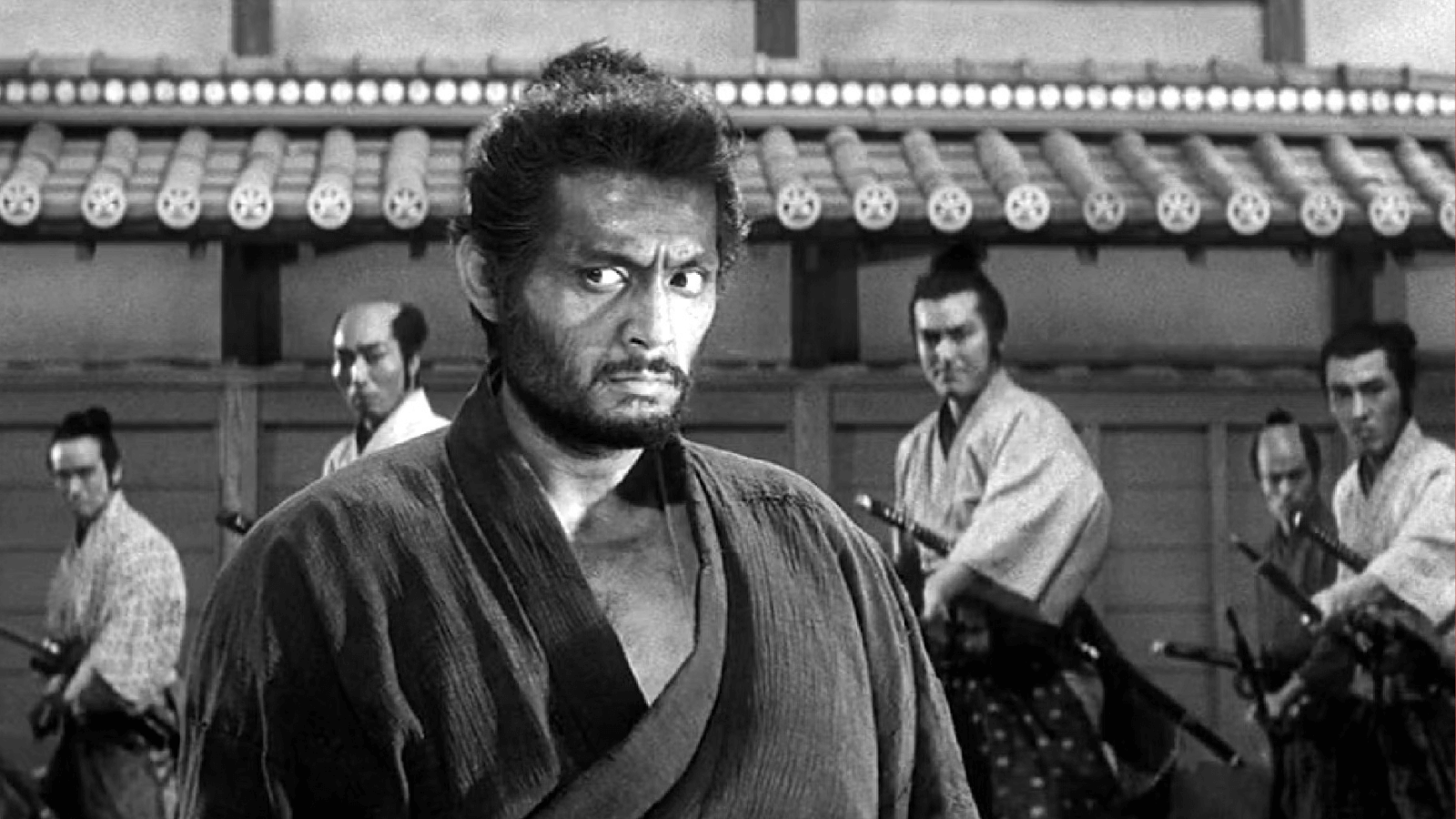

Nakadai, an actor of deliberate movements and profoundly severe intention, captures the precise tone of the film in his grave performance. Kobayashi discovered Nakadai working as a store clerk in Tokyo in the early 1950s; noticing his deep voice and intense eyes, the director cast him in The Thick-Walled Room. Through the 1980s, this director-actor partnership lasted eleven collaborations in all. Having worked with directors including Kurosawa, Hideo Gosha, Kon Ichikawa, Mikio Naruse, and Hiroshi Teshigahara, Nakadai achieved celebrity status in Japan and beyond, being surpassed in popularity by only one or two other actors, namely Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura. He appeared in many iconic films, such as The Human Condition (1959), When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960), Yojimbo (1961), Sanjuro (1962), Sword of Doom (1966), Kagemusha (1980), and Ran (1985), to name just a few. Nakadai stands out because his acting style appears less stagey and more subtle than many Japanese actors who learned their craft from theatrical techniques such as Noh and Kabuki. Rather, he trained in the Japanese New Theater movement called Shingeki, which rejected those traditions in favor of a modern realism that mirrored twentieth-century Western theatrical styles. As a result, his style frequently relied on a complex interiority, complete with a stoic exterior that offered hints of something more complicated under the surface. Known for his piercing onscreen presence, he puts forth arguably his most remarkable performance in Harakiri with a combination of tired resolve, contained fury, and brutal violence.

Hashimoto’s script continues to ratchet tension when, in the temple’s square, Tsugumo requests the Iyi clan’s top swordsman, Hikokuro Omodaka (Tetsuro Tanba), as his second. While a runner checks if Omodaka and two other top swordsmen, who have all been ill for days, can perform these duties, Tsugumo gives an account of his sad story to the attendees and suggests, “What befalls others today may be your own fate tomorrow.” Tsugumo then declares that he served as an adopted father to Chijiiwa, who bore a son with his daughter. When poverty sent Chijiiwa’s wife and son into illness, he sold his sword and hoped he could earn himself some pittance from the Iyi clan. Humiliated and forced into performing torturous suicide in the name of samurai honor, Chijiiwa never returned, so his wife and child died. When Saito hears this, he insists that Tsugumo picks another second, but the rugged samurai refuses and admits he has no intention of executing harakiri. Tsugumo does not expect an apology, simply an acknowledgment from Saito that the Iyi clan went too far in making an example out of Chijiiwa. When Saito refuses, Tsugumo accuses the clan’s samurai honor of being false, exposing how the three top swordsmen who claim to be ill are hiding from embarrassment. In the preceding days, Tsugumo engaged each in duels and removed their topknots, the hair grown and folded forward on top of the head to symbolize samurai status. Tsugumo tosses the topknots before Saito, laughing with contemptuous scorn, and in doing so, reveals the clan’s shameful behavior.

The film ends with a samurai battle when Saito orders his retainers to attack Tsugumo, who defends himself against dozens of men and kills many of them in the fight. Desperate to regain control, a squad of riflemen arrives on the scene to shoot Tsugumo. In his last moments, Tsugumo pulls down the Iyi clan’s ceremonial armor, and then he attempts to achieve some measure of samurai honor by impaling himself with his long sword. As Prince notes, his last-minute impulse to commit seppuku suggests that, despite recognizing how the Iyi clan has warped the bushido code to inflict cruelty on Chijiiwa, he remains committed to those ideals. This might be the film’s most tragic statement on the faulty and corrupting nature of militarized ideology on people. Tsugumo believes in the samurai code, to the point that he never considered selling his swords, despite his daughter and grandson living in such poverty that they died. By contrast, Chijiiwa was willing to give up his samurai weapons and exploit the Iyi clan’s belief in the code to preserve his family, recognizing that his wife and daughter meant more than the false notions of honor instilled by bushido. Even though Tsugumo has gone to great lengths to challenge the clan’s hypocrisy, the film’s hero never escapes the belief system that outlines the vital need to achieve an honorable death through ritual suicide. Harakiri is a cynical acknowledgment that people sometimes cannot escape corrosive systems even after becoming aware of their deceptions.

The film ends with a samurai battle when Saito orders his retainers to attack Tsugumo, who defends himself against dozens of men and kills many of them in the fight. Desperate to regain control, a squad of riflemen arrives on the scene to shoot Tsugumo. In his last moments, Tsugumo pulls down the Iyi clan’s ceremonial armor, and then he attempts to achieve some measure of samurai honor by impaling himself with his long sword. As Prince notes, his last-minute impulse to commit seppuku suggests that, despite recognizing how the Iyi clan has warped the bushido code to inflict cruelty on Chijiiwa, he remains committed to those ideals. This might be the film’s most tragic statement on the faulty and corrupting nature of militarized ideology on people. Tsugumo believes in the samurai code, to the point that he never considered selling his swords, despite his daughter and grandson living in such poverty that they died. By contrast, Chijiiwa was willing to give up his samurai weapons and exploit the Iyi clan’s belief in the code to preserve his family, recognizing that his wife and daughter meant more than the false notions of honor instilled by bushido. Even though Tsugumo has gone to great lengths to challenge the clan’s hypocrisy, the film’s hero never escapes the belief system that outlines the vital need to achieve an honorable death through ritual suicide. Harakiri is a cynical acknowledgment that people sometimes cannot escape corrosive systems even after becoming aware of their deceptions.

The film’s ending raises questions about governments and their false commitment to the principles they espouse, especially bushido. Although the feudal daimyo structure eventually crumbled in 1868, when the Tokugawa shogunate fell with the Meiji Restoration, the reawakening of Japan’s militarism during the Second World War reified the bushido code’s ideals and once more proved them faulty. Kobayashi demonstrates that the codes of militaristic governments are a pretense of establishing power and social hierarchies, leaving humanity in its wake. Further, the film explores how even a lone individual bent on revolt can threaten the delicate arrangement of repressive authority, as Tsugumo tears down the Iyi clan armor in his final moments before the clan resorts to dishonorably gunning down their skilled swordsman opponent. Even though the Iyi clan quickly restores itself after Tsugumo’s death, the film recognizes the importance of a single ronin usurping the clan and dismantling their emblematic armor, even if the act itself disappears when the victors write their history books and claim all casualties were lost to illness. “An incident of significance has taken place, while remaining unrecorded in official history, as though all were calm and nothing had ever happened,” Kobayashi noted. “That is the deceit of history.” In the final scenes, the Iyi clan’s restored samurai armor now exhibits a symbol of continued hypocrisy through the ages in samurai nobility, and for Kobayashi, all systems of authority.

While containing all necessary elements for Japanese cinema’s popular samurai-themed jidai-geki, conforming to its period requirements and even boasting impressive swordplay in the finale’s battle scenes, Harakiri serves as a potent anti-samurai film. The bushido code becomes the device by which the characters are betrayed on a humanist level. At the same time, the way of the warrior fails to address the implications when honor conflicts with protecting one’s family. Tsugumo and Chijiiwa, unlike the typically spartan samurai in many jidai-geki, deem family the principal component in their lives, engaging in marriage or maintaining the parent-daughter relationship out of love, never for convenience or opportunity. When Chijiiwa’s family becomes destitute, he sells his blades and his samurai identity, and he resolves that love is more important than honor. Later, Tsugumo curses himself for not doing the same, whereas the Iyi clan sees only the offense against samurai honor and not the needs of the individual human. Through the Iyi clan, Kobayashi slams such blind power structures adhered to in Japanese culture—those that demand the individual submit oneself to group control because power structures so commonly dissolve individual human concerns. Tsugumo makes Kobayashi’s thematic objectives explicitly clear when he says, “This thing we call samurai honor is ultimately nothing more than a façade.”

When Harakiri premiered on September 16, 1962, Japanese audiences saw the familiar cinematic landscape of feudal Japan portrayed in expressive, albeit precise allegorical terms from Kobayashi’s poetic use of space, stagelike lighting, and widescreen compositions. The director communicates his themes in rigorous formalist grammar, visually conveying intolerable class regimentation through calculated movements of the frame, symmetrical compositions, and theatrical lighting representing the rigid authority of ruling institutions. A limited number of sets, used repeatedly to create a sense of space and sameness to reflect ritualistic behavior patterns, might become claustrophobic with another filmmaker. Kobayashi’s frequent cinematographer Miyajima utilizes fluid extended takes contrasted by sharp camera tilts to make the frame’s position, movement, and subtle contorting essential and telling narrative tools. Moreover, the actors used actual blades during production, which accounts for the slower movements compared to, say, Toshiro Mifune’s swift swordplay in Yojimbo and Sanjuro. But also, as Prince observes, Kobayashi did not have the same interest in spectacle or sometimes reverent uses of bushido that Kurosawa did. While Kurosawa could blend his critique of samurai heritage into a rousing adventure filled with cinematic sword fighting, Kobayashi actively worked against Kurosawa’s period films. In an interview with Shinoda Masahiro, the director admitted, “In a sense, I was challenging [Kurosawa].” Indeed, Kobayashi’s critique of inflexible systems of power remained his central purpose, whereas Kurosawa often found dignity in bushido honor.

When Harakiri premiered on September 16, 1962, Japanese audiences saw the familiar cinematic landscape of feudal Japan portrayed in expressive, albeit precise allegorical terms from Kobayashi’s poetic use of space, stagelike lighting, and widescreen compositions. The director communicates his themes in rigorous formalist grammar, visually conveying intolerable class regimentation through calculated movements of the frame, symmetrical compositions, and theatrical lighting representing the rigid authority of ruling institutions. A limited number of sets, used repeatedly to create a sense of space and sameness to reflect ritualistic behavior patterns, might become claustrophobic with another filmmaker. Kobayashi’s frequent cinematographer Miyajima utilizes fluid extended takes contrasted by sharp camera tilts to make the frame’s position, movement, and subtle contorting essential and telling narrative tools. Moreover, the actors used actual blades during production, which accounts for the slower movements compared to, say, Toshiro Mifune’s swift swordplay in Yojimbo and Sanjuro. But also, as Prince observes, Kobayashi did not have the same interest in spectacle or sometimes reverent uses of bushido that Kurosawa did. While Kurosawa could blend his critique of samurai heritage into a rousing adventure filled with cinematic sword fighting, Kobayashi actively worked against Kurosawa’s period films. In an interview with Shinoda Masahiro, the director admitted, “In a sense, I was challenging [Kurosawa].” Indeed, Kobayashi’s critique of inflexible systems of power remained his central purpose, whereas Kurosawa often found dignity in bushido honor.

After winning the Special Jury Prize at Cannes in 1963, Harakiri and Kobayashi earned international renown. The director spent six weeks traveling around Europe and making connections with fellow filmmakers such as Ingmar Bergman, establishing himself as not just a Japanese auteur but an international filmmaker—thus ensuring that his subsequent films, Kwaidan (1965) and Samurai Rebellion, would earn worldwide distribution. Prince compared Harakiri to Kurosawa’s Rashomon in that the film helped elevate him “to a new level of status and prestige.” Critic David Sterritt said it best: “Kobayashi’s graduation from gifted director to world-class director happens with Harakiri.” But as Kobayashi’s output continued to be critical of the establishment, his celebrity and the frequency of his employment waned. Studios wanted to avoid uncertain ventures that might antagonize the United States’ occupational army; after all, his reputation was that of a filmmaker who takes risks, not one who makes surefire box-office successes. And so, Kobayashi, along with Akira Kurosawa, Keisuke Kinoshita, and Kon Ichikawa, dropped from the studio system and formed the independent film company Yonki-no-Kai, the Club of the Four Knights. Unfortunately, their productions began with Kurosawa’s Dodes’ka-den in 1970, which led to a commercial failure, with many more underwhelming features to follow. And though Kurosawa would go on to reinvent his work with Kagemusha and Ran, Kobayashi left his best and most controversial films behind him.

Subverting authority on the basis of human decency, Harakiri endures as Kobayashi’s most powerful film and an uncommonly singular statement against the empty promises of samurai honor. The director’s formalist aesthetic underscores the mannered, surface-level artificiality of political ideology. The film’s condemnation of the lies systems of authority will tell to preserve their power and engrain their ideology is deeply felt and presented in a structure that leaves the viewer rife with indignation and saddened by the tragic story of Tsugumo’s family. Although Harakiri’s direct target is the bushido code that has influenced Japan for hundreds of years and carried the country into the disastrous World War II, Kobayashi’s sentiments transcend samurai honor, the feudal period, and twentieth-century history. The film confronts the whole of human history and remains a vital illustration of the illusory nature of political power, even, and perhaps especially, today. Under Kobayashi’s direction, Japanese warriors revered for centuries as symbols of military composure, honor, and nobility become hardened figures of corruption and emotional indifference, further outlining how systems of authority use their principles to maintain power and manipulate the individual.

Bibliography:

Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. Norton & Company, 1999.

McDonald, Keiko I. Reading a Japanese Film: Cinema in Context. University of Hawaii Press; annotated edition, 2006.

Richie, Donald; Schrader, Paul. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Video. Kodansha America, 2005.

Prince, Stephen. A Dream of Resistance: The Cinema of Kobayashi Masaki. Rutgers University Press, 2017.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review