The Definitives

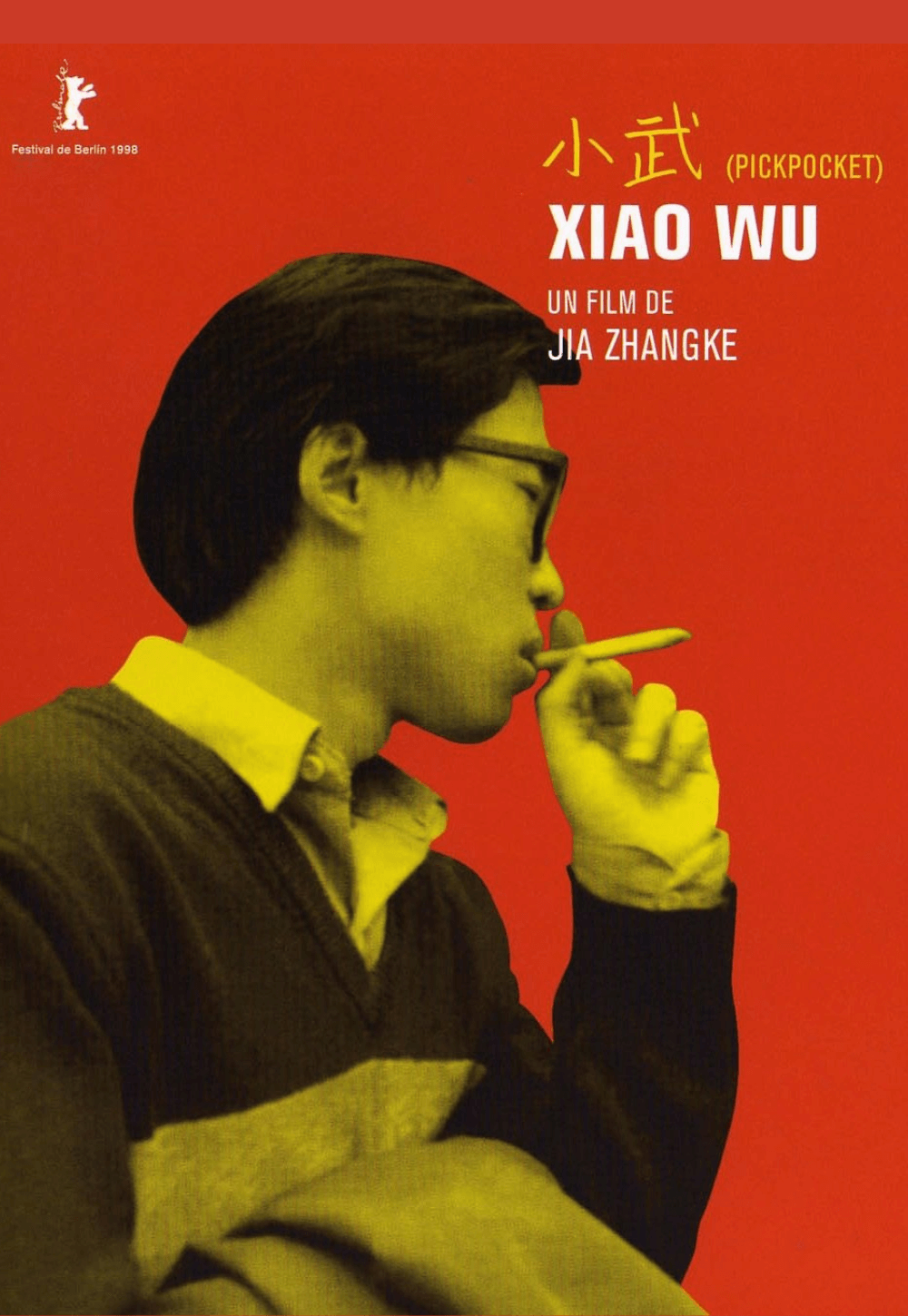

Happy-Go-Lucky

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The unyielding cheeriness of Poppy, the central figure of Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky, played by an effervescent Sally Hawkins, could be mistaken as false or naiveté. The world’s supply of optimism is, after all, running short. Poppy first appears on a bike over the opening titles, her face brimming with a smile during a pleasant journey around London, set to Gary Yershon’s blithe score. She ventures into a bookstore where, attempting to make a connection with the uninterested clerk, she selects a book called The Road to Reality from the shelf at random. “Don’t wanna be going there,” she jokes. The clerk continues to ignore her attempts at levity, conversation, and even a casual flirtation until finally, she leaves the store. She discovers that her bike has been stolen and, rather than respond with anger or assume the universe is working against her, she meets the situation unfazed and with a bemused response: “Didn’t even get a chance to say goodbye.” Without irony or malice, the British filmmaker’s character study reveals a rare and sophisticated breed of human being whose happiness comes from within, and whose optimistic personality is less of a departure for the filmmaker than it might initially seem. Leigh’s tendency for humor within his occasionally stark, stylized realism permeates Happy-Go-Lucky, whereas his portrait of an optimist is something altogether unique among the characters in his body of work. However, the world Poppy inhabits is no fantasy of her creation; she faces cruelty, narrow-mindedness, aggression, and solitude. But her philosophy towards life means that she greets the darker aspects of the world with inspiring compassion and fearlessness.

To appreciate how Happy-Go-Lucky dwells both within and outside of Leigh’s usual framework, some background may prove useful. The British director was born in 1943. He studied acting, drawing, theater, and film throughout the 1960s, and he used what he learned from his intense collaborations with actors on the stage and his experiences observing life in the pursuit of art to launch a career in filmmaking. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Leigh made a series of shorts and low-budget feature-length films about working-class people, viewed predominantly by a television audience. Many British filmmakers from Stephen Frears to Peter Greenaway functioned within a system whereby the BBC and Channel Four acquired films for the small screen. Their subjects were deemed too intimate for theatrical distribution; however, they were far removed from the TV movies of the United States, whose melodramatic and topical plots from this era range from spousal abuse to a boy in a plastic bubble. Leigh and his contemporaries made pictures about everyday people struggling to endure under Thatcher-era political and social conditions. Thatcherism, which allowed unemployment rates to rise and created more significant division between the upper and lower classes, felt nothing but antipathy for the unemployed or those overlooked by the culture’s new obsession with capitalist consumption and the status it afforded. Whereas other filmmakers used this backdrop to carry an anti-establishment agenda, Leigh’s early films put a human face on those abandoned by Thatcherism, often with a bemused, sardonic use of portraiture. From his 1971 debut Bleak Moments to his 1990 family drama Life Is Sweet, Leigh told intimate stories about ordinary people who sometimes resemble comic caricatures, if only to accentuate their status as the forgotten. In the next decades, Leigh’s penchant for realistic, albeit exaggerated portraits of his characters became increasingly severe, starting with Naked (1993), followed by his Palme d’Or winner Secrets & Lies (1996) and All or Nothing (2002).

Regardless of their style or subject matter, his films often inhabit bleak social situations. They are about everyday people who do their best to get by, whereas traditionally, mainstream cinema requires its characters to accomplish something, to have an arc in which they strive for an outcome, take a journey, resolve a conflict, save the day, or fall in love. Leigh makes character studies, which are not about a character’s ability to untangle a situation or achieve a particular ambition. His longtime collaborator Timothy Spall observed, “I’ve discovered over and over that he makes films at the centre of which he puts the sort of people who most other people are thankful not to be. He gives them nobility. That is his genius.” His advantage as a filmmaker is his gift as a social observer, someone who looks beyond the dramatic arc of most stories rooted in so-called cinematic realism and instead examines the lives of people who often have no way out of their situation. Then again, the situation of any Leigh film is simply the essence of his characters and the reality of their lives; they can no more escape their situation than any of us can escape our existence. As observed by Ray Carney and Leonard Quart, Leigh’s strength is to “ask questions rather than provide answers and to take pleasure in both lamenting and laughing at the human predicament.”

Regardless of their style or subject matter, his films often inhabit bleak social situations. They are about everyday people who do their best to get by, whereas traditionally, mainstream cinema requires its characters to accomplish something, to have an arc in which they strive for an outcome, take a journey, resolve a conflict, save the day, or fall in love. Leigh makes character studies, which are not about a character’s ability to untangle a situation or achieve a particular ambition. His longtime collaborator Timothy Spall observed, “I’ve discovered over and over that he makes films at the centre of which he puts the sort of people who most other people are thankful not to be. He gives them nobility. That is his genius.” His advantage as a filmmaker is his gift as a social observer, someone who looks beyond the dramatic arc of most stories rooted in so-called cinematic realism and instead examines the lives of people who often have no way out of their situation. Then again, the situation of any Leigh film is simply the essence of his characters and the reality of their lives; they can no more escape their situation than any of us can escape our existence. As observed by Ray Carney and Leonard Quart, Leigh’s strength is to “ask questions rather than provide answers and to take pleasure in both lamenting and laughing at the human predicament.”

Happy-Go-Lucky finds Leigh continuing a mode of realism with a lessened degree of caricature. It feels more nuanced and less rooted in comic observations than Leigh’s earlier work, primarily due to the complexity of his protagonist. At thirty, Poppy runs the risk of not being taken seriously. She spends her weekends decompressing with her younger sister Suzy (Kate O’Flynn) and best friend Zoe (Alexis Zegerman) at raucous concerts. Her style might be called tacky—she dresses in conflicting prints and animal patterns, omnipresent heeled boots, bright colors, and casually thrown together hairstyles. She’s always smiling, always has a joke or amused expression. But this is not out of deflection or in service of some dark visage of her personality that she hopes to mask. Poppy is neither an oblivious, empty-headed person nor is she secretly sad or artificially upbeat; her happiness draws from a profound experience of world travel and teaching. She leads a genuinely pleasant life with her flatmate Zoe, another single, unmarried woman not interested in conforming to the social expectations of someone her age. The morning after a Pulp concert, Leigh shows Poppy and Zoe making bird costumes out of brown paper bags, glue, and decorations. At first, their creative project seems like another sign of an irresponsible bohemian lifestyle, which someone more judgmental might deem childish, except they are preparing for their respective elementary school classes, where both serve as imaginative and caring teachers.

As a teacher, Poppy is an observer and assessor of people, and teachers play a central role in Happy-Go-Lucky. Almost every major character is a teacher of some kind. Poppy and her sisters teach, so do Zoe and several supporting characters. Heather (Sylvestra Le Touzel), the principal at Poppy’s school, convinces Poppy to join her for flamenco lessons. The instructor, Rosita (Karina Fernandez), fuels her skills as a teacher and artist with a romantic sense of passion—at one point, Rosita storms out of a lesson after revealing a painful detail about her love life. Later, she returns to the class, her composure and enthusiasm for dance restored. Working with another sort of energy is Scott (Eddie Marsan), a private driving instructor whom Poppy hires so she can get an automobile to replace her stolen bike. During his strict, humorless lessons that attempt to bring systemic order to Poppy’s life, he complains that her heels are inappropriate for driving, talks about the threats of multiculturalism, demands that she locks the car doors when two black men pass by, and represses his sexual attraction to her until the casual tension between them explodes. If most characters are teachers in the film, Leigh seems to ask the question, what can we learn from them?

Whatever misconceptions the viewer has about Poppy at first are corrected by her interactions with friends, students, and colleagues, where her jokey mannerisms also stand as evidence of her active participation in a shared social exchange. When Poppy talks to someone, she is fully engaged, as other people are what interest her most about the world. However, there’s a pattern among some people who dismiss her altogether because she makes jokes, dresses a certain way, or does not approach education with the same teaching philosophy. Strangely, Poppy never changes or grows in Happy-Go-Lucky, but the characters around her change because they have been exposed to her worldview. Our experience with the film is similar. Although the title and some of Poppy’s behavior may seem carefree or ridiculous, to watch the film is to understand that she takes everything in—the good as well as the bad—and sees the beauty in it. During a later scene, when she looks out at a cloudy sky in the morning, she reflects on its beauty. One suspects that it could be raining or snowing, but Poppy would still be able to locate the beauty of the moment. Her definition of beauty is far-reaching in the most remarkable of ways.

Whatever misconceptions the viewer has about Poppy at first are corrected by her interactions with friends, students, and colleagues, where her jokey mannerisms also stand as evidence of her active participation in a shared social exchange. When Poppy talks to someone, she is fully engaged, as other people are what interest her most about the world. However, there’s a pattern among some people who dismiss her altogether because she makes jokes, dresses a certain way, or does not approach education with the same teaching philosophy. Strangely, Poppy never changes or grows in Happy-Go-Lucky, but the characters around her change because they have been exposed to her worldview. Our experience with the film is similar. Although the title and some of Poppy’s behavior may seem carefree or ridiculous, to watch the film is to understand that she takes everything in—the good as well as the bad—and sees the beauty in it. During a later scene, when she looks out at a cloudy sky in the morning, she reflects on its beauty. One suspects that it could be raining or snowing, but Poppy would still be able to locate the beauty of the moment. Her definition of beauty is far-reaching in the most remarkable of ways.

This is contrasted by Scott, whose caustic temper and unfurled teeth would make any student nervous. He interprets his role as an instructor thus: “The teacher’s job is to bring out good habits in the pupil and to get rid of bad habits. He does that through frequent repetitive thinking. And he does that by creating clear and distinct images that are easy for the pupil to retain.” When he isn’t expounding a racist dogma, he explains his teaching tool as a “golden triangle” between the car’s mirrors, likening them to a pyramid, at the top of which is the rear-view mirror, the all-seeing eye, which he dubs “Enraha.” There were two fallen angels before Lucifer, Scott explains in a bit of wacked mysticism, and Enraha was one of them. “Are you a Satanist, Scott?” Poppy jokes. “No, in fact, I’m the exact opposite,” he replies. “Are you the Pope, then?” she laughs. “It’s the same thing,” Scott remarks in a line that denotes some manner of fanaticism that drives him. At each lesson, Scott’s anger with Poppy and her curiosity about his beliefs increases, and he responds by shouting his instructions. “Enraha,” he commands repeatedly, then tells Poppy, “you’re too easily distracted. You’re distracted by squirrels, by dogs, by children in the park.” Poppy laughs through Scott’s lessons, making him even angrier. But Scott insists, “You will remember Enraha ’til the day you die, and I would have done my job.” After a lesson with Scott, Poppy returns to her flat. Zoe asks her how the driving lesson went, and Poppy replies, “Dark.”

Her response might be a gross understatement, but it also reveals Poppy’s patience with people, and her willingness to give them every chance. When she looks out of the classroom window to see one of her students, Nick (Jack MacGeachin), attacking another boy on the playground, she does not approach the situation with scolding or punishment. Instead, she talks to Nick and, along with the help of a handsome social worker named Tim (Samuel Roukin), discovers the troubles at home that have caused the boy to lash out at school. Another scene of Poppy’s resounding empathy comes when she walks home one night through a bad neighborhood and hears a strange singing, almost chanting from inside an abandoned industrial space. She finds a homeless man (Stanley Townsend) talking to himself in a repetition that suggests some psychological malady. “You know what I mean? You know?” he says again and again, not unlike the frequency with which Scott repeats “Enraha.” Another person would dismiss the man as a raving lunatic, but Poppy approaches him, visibly cautious, kindly asking if he’s warm enough and has enough to eat. She offers him money and food, but he replies only in incoherent rants. And yet, they make a brief, unmistakable connection. What is marvelous about this quiet, even haunting scene is how Poppy approaches it not merely as a Good Samaritan trying to help someone in need, but the apparent curiosity she has towards another human being—in hopes of building some kind of rapport, and then learning something from the experience.

Structurally, the film unfolds as a series of random events in Poppy’s life, as much as anything in anyone’s life is random. She subsists on a weekly routine, teaching during the day, exercising on a trampoline in the morning, taking a flamenco lesson in the evening, going to the chiropractor because the trampolining has thrown out her back, taking her driving lesson with Scott, and unwinding on the weekend with Suzy and Zoe. There is not a strong linear progression to these events; Leigh avoids typical narrative trajectories for the most part. Though, he does concede to a romantic subplot in Happy-Go-Lucky when Poppy meets Tim, and their future together seems assured. Otherwise, the film might appear episodic, except that the point of the film might be for the viewer to identify with Poppy’s approach to the world, which is less a series of individual episodes than an attempt to experiment, try new things, meet new people, and learn something from the process. She explains to Heather early on that she and Zoe traveled the world after college, teaching in Thailand for a stint. And while it might seem as though she sees the world as entertaining given her use of humor and laughter, it’s more accurate that she finds it edifying. Now in her thirties, Poppy still maintains a youthful curiosity about the world.

Structurally, the film unfolds as a series of random events in Poppy’s life, as much as anything in anyone’s life is random. She subsists on a weekly routine, teaching during the day, exercising on a trampoline in the morning, taking a flamenco lesson in the evening, going to the chiropractor because the trampolining has thrown out her back, taking her driving lesson with Scott, and unwinding on the weekend with Suzy and Zoe. There is not a strong linear progression to these events; Leigh avoids typical narrative trajectories for the most part. Though, he does concede to a romantic subplot in Happy-Go-Lucky when Poppy meets Tim, and their future together seems assured. Otherwise, the film might appear episodic, except that the point of the film might be for the viewer to identify with Poppy’s approach to the world, which is less a series of individual episodes than an attempt to experiment, try new things, meet new people, and learn something from the process. She explains to Heather early on that she and Zoe traveled the world after college, teaching in Thailand for a stint. And while it might seem as though she sees the world as entertaining given her use of humor and laughter, it’s more accurate that she finds it edifying. Now in her thirties, Poppy still maintains a youthful curiosity about the world.

Still, Poppy’s otherwise irrepressible good-humor has limits, not because her optimism is unnatural but because there are those who choose to close themselves off from the world. Leigh shows some measure of empathy for most characters in the film; however, he has no tolerance for suburban living. In a later scene, Poppy, Zoe, and Suzy visit the middle sister in their family, Helen (Caroline Martin), who is married to Jamie (Oliver Maltman) and expecting a child. Inside their carefully designed suburban home with color-coordinated furniture, Helen lives inside a bubble, and Poppy does not approve of their stifled, unengaged isolation. In an interview with Cinéaste, Leigh censures “the neurotic compulsion for respectability” of suburbia and its “mortgage-bound, structured, conventional” lifestyle that removes Helen and Jamie from the world and renders them unhappy. Watch the sad moment where Jamie shows enthusiasm for his video games, but Helen refuses to let him play. Similarly, someone as unbending as Scott, who has buried his wounds so deep that he refuses to acknowledge the cause, make this world a difficult place to live in, even for Poppy. Her driving lessons with Scott eventually reach a hostile, even dangerous climax when, out of sheer frustration, his repressed attraction to Poppy builds to a violent outburst. He spies on her and sees her with Tim, which makes him jealous and aggressive, feelings he later denies in their next lesson. When he acts out against her, Poppy’s last resort is to walk away, though her patience has extended far beyond the limits of the average person. It is only when Scott’s behavior turns hostile that she refuses to accept another lesson.

Perhaps it goes without saying that Happy-Go-Lucky hangs on the brilliant and infectiously joyful Sally Hawkins, who embodies Poppy in the type of fully lived-in performance associated with all of Leigh’s work. His method of working with actors is famous for creating three-dimensional characters through a process shrouded in secrecy, workshopping, and improvisational order. The director collaborates with an actor on an individual basis for several months in advance of any shooting, and the actor must devise a character based on one or more people they know. Through a long rehearsal process, anywhere from three to six months or more of preparation, the background and various aspects of the character’s life are filled in, and the actor begins to react organically to situations in their character’s voice. Actors work with Leigh to research the details of their characters’ lives and flesh-out any details that will enhance the authenticity of the role. However, the actors are expected to empathize with their characters, not become them—a distinction that some have failed to make. Spall describes the process as “creating a parallel universe.”

Leigh remains the only person with a full vision of the overall film and what he intends to capture oncreen, but even those concepts are fluid and can transform through the entrenched collaboration process. For instance, Marsan remarked in a supplementary feature for Happy-Go-Lucky’s release on home video that he believed his character was conceived as part of a darker breed of Leigh film, similar to Naked, but he later realized this was not the case—his role as Scott was a kind of “antithesis” to Poppy. To be sure, when shooting begins, the actors remain unaware of the bigger picture—they are only aware of the scenes they have figured out through elaborate improvisations with their fellow actors and discussions with Leigh about what feels right. Every single scene derives from several hours of preparation, exploring the nature of the scene and its characters through intense study and experimentation, distilling the dialogue down to its core to avoid repetition, and refining what will be shot. Actors from Lesley Manville to Imelda Staunton have called Leigh’s immersive process the most challenging but rewarding work of their careers. Other actors, those who see playing a role as nothing more than a job, have walked away from the process altogether.

Leigh remains the only person with a full vision of the overall film and what he intends to capture oncreen, but even those concepts are fluid and can transform through the entrenched collaboration process. For instance, Marsan remarked in a supplementary feature for Happy-Go-Lucky’s release on home video that he believed his character was conceived as part of a darker breed of Leigh film, similar to Naked, but he later realized this was not the case—his role as Scott was a kind of “antithesis” to Poppy. To be sure, when shooting begins, the actors remain unaware of the bigger picture—they are only aware of the scenes they have figured out through elaborate improvisations with their fellow actors and discussions with Leigh about what feels right. Every single scene derives from several hours of preparation, exploring the nature of the scene and its characters through intense study and experimentation, distilling the dialogue down to its core to avoid repetition, and refining what will be shot. Actors from Lesley Manville to Imelda Staunton have called Leigh’s immersive process the most challenging but rewarding work of their careers. Other actors, those who see playing a role as nothing more than a job, have walked away from the process altogether.

Given this profoundly engaging relationship in which actors locate and develop their characters with Leigh, there are no scripts to most of Leigh’s productions. No dialogue has been transcribed onto paper. The process of understanding a scene is achieved by everyone involved knowing their role, which has been arrived at after countless hours of workshopping. Despite Leigh’s credit as writer and director, his process consists of an extended, very private, and unconventional rehearsal with no traditional screenplay. Leigh is the writer insomuch as he oversees “an evolving film in his head,” and his job as the director is “the task of organizing the proceedings so as to make them progress usefully.” Although Leigh has been accused of having no idea where his films will go once he starts, he has also been accused of being a master manipulator who draws his performers towards his grand, preconceived vision for a film. He claims that both perceptions are true: his process is one of advanced preparation in service of the film, and he also allows his cast and crew the freedom of creativity and spontaneity once shooting begins. Whichever story you believe about his films, the result is a small miracle of artistic creation.

An argument against the randomness of Leigh’s approach can be found in the recurrent themes of his work, which reveal the signs of an author interested in ordinary people, “the entirely disorganized and irrational business of living,” as he calls it. The ordinariness of his characters, especially in the first half of Leigh’s career, could be defined by a certain miserabilist outlook. But Happy-Go-Lucky—along with his 2010 film Another Year, about a couple’s enduring marriage amid the melancholy of their friends and family—finds nobility in optimism and openness. Formally, the film embraces Poppy’s beliefs about life, insofar as Leigh employs brighter and more enlivened colors than his usual muted color palette, and cinematographer Dick Pope uses Fuji film stock called Eterna Vivid to heighten the rich use of color that surrounds the central character. If its brightness and pleasantness seem less weighty than the abortion-themed Vera Drake (2004) or the drives of his acerbic Naked, where David Thewlis’ anti-hero Johnny is an idealist whose perspective is exaggerated by every example of humanity’s failure, it should not suggest the film’s lack of insight. Poppy’s optimism comes not as a reaction to the world but from inside herself, and therein, the film has a profundity of its own.

Though at every turn Poppy’s life is more complicated than her optimism, a small contingent of critics maintain that Leigh’s portrait of Poppy is false or, as one critic put it, “an air-headed vision of inner contentment.” Such a cynical perspective refuses to acknowledge that pure happiness can exist in a person, and further, deems happiness somehow ignorant. After the film premiered at the Berlin Film Festival, Leigh told an interviewer that “If people have a problem with Poppy, I am quite convinced that the problem is their problem.” Leigh goes on to describe the scene with Poppy’s sister Helen, who tells her, “I don’t think you’re happy.” This is more of a reflection of Helen than of Poppy, according to Leigh; the same is true of the critics who interpret Poppy’s behavior as that of someone simple-minded or privately miserable. “There is no irony or subtext intended—no secret tragedy is revealed,” said Leigh in another interview. “Poppy isn’t naive or innocent, she is a sophisticated single woman of thirty who has traveled and been around. She’s observant, vivacious, open, and at ease in the world.” It is a sophistication befitting Sherwood Anderson.

Though at every turn Poppy’s life is more complicated than her optimism, a small contingent of critics maintain that Leigh’s portrait of Poppy is false or, as one critic put it, “an air-headed vision of inner contentment.” Such a cynical perspective refuses to acknowledge that pure happiness can exist in a person, and further, deems happiness somehow ignorant. After the film premiered at the Berlin Film Festival, Leigh told an interviewer that “If people have a problem with Poppy, I am quite convinced that the problem is their problem.” Leigh goes on to describe the scene with Poppy’s sister Helen, who tells her, “I don’t think you’re happy.” This is more of a reflection of Helen than of Poppy, according to Leigh; the same is true of the critics who interpret Poppy’s behavior as that of someone simple-minded or privately miserable. “There is no irony or subtext intended—no secret tragedy is revealed,” said Leigh in another interview. “Poppy isn’t naive or innocent, she is a sophisticated single woman of thirty who has traveled and been around. She’s observant, vivacious, open, and at ease in the world.” It is a sophistication befitting Sherwood Anderson.

Leigh told interviewer Amy Raphael that his films are about “how we live and survive.” But the ways in which anyone lives and survives are never simple; they are intimate and refuse to conform to the narrative conventions of cinema. Happy-Go-Lucky shows a different method of survival than viewers of Leigh’s cinema are accustomed, though it is no less serious nor funny than any of his other work. Rather than being aligned with a predominant and, frankly, much easier cynicism towards to the world, as many of Leigh’s characters tend to have, Poppy demands, by way of her mere presence, that we strive to understand the world with a higher degree of empathy, which enriches the viewer. The cheeriness and brightness of her example feed one of the most complex of Leigh’s films, in that it requires engagement with Poppy’s thoughts and feelings, as well as an awareness of our own lives and emotions to process this character study with the depth it deserves. Leigh and Hawkins have created an enduring character, among the most heartening in all of cinema, who inspires us to reflect on our world in both emotional and intellectual terms, and furthermore, accept that an openness and curiosity about the world is rewarding, even if we remain uncertain of where such receptivity will lead.

Bibliography:

Cardinale-Powell, Brian and Marc DiPaolo, editors. Devised and Directed by Mike Leigh. Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Carney, Ray, and Leonard Quart. The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

O’Sullivan, Sean. Mike Leigh. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Quart, Leonard. “Being Positive: An Interview with Mike Leigh.” Cinéaste, vol. 33, no. 4, 2008, p. 54.

Raphael, Amy, editor. Mike Leigh on Mike Leigh. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008.

Vineberg, Steve. “Realism, Two Ways.” The Threepenny Review, no. 117, 2009, pp. 23–25.

Watson, Gary. The Cinema of Mike Leigh: A Sense of the Real. Wallflower Press, 2004.

Whitehead, Tony. Mike Leigh. Manchester University Press, 2007.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review