The Definitives

Halloween (1978)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Halloween is John Carpenter’s most analyzed work. Spectators have drawn sundry conclusions about its meaning and symbolism since its initial release, and the obsession has lingered for decades. Horror fans and scholars alike have presented elaborate theories that assign every detail in the film a meaning according to their interpretation of its terror. Something about Michael Myers, behind the void of his expressionless white mask, allows viewers to access their deepest fears and project them upon that face. And yet, the simplicity and straightforwardness of the filmmaking, from Dean Cundey’s widescreen cinematography to the natural characterizations, from Carpenter’s memorable score to the screenplay’s efficiency, amount to a terrifically crafted motion picture. But the movie reaches beyond its confident technical execution and grabs at the audience, putting viewers through a troubled nightmare of suspense and uncertain dread. It reaches into our deepest, most primitive anxieties of the unknown and then exploits them. Halloween is a cipher that moviegoers, critics, and film scholars have filled in with countless readings, some of which will be explored in the ensuing paragraphs. What remains after the movie’s deceptive simplicity and superb form is its haunting ability to mean whatever we need it to mean, and therein retain the unfettered horror it inspires in our subconscious.

Halloween was released during an era that gave birth to some of cinema’s most interpretable films and most ambiguous endings, titles that audiences have debated and theorized about ever since their debut. The cinema of the 1970s refused to give audiences easy explanations or closure, reflecting an era still reeling from Richard Nixon’s presidency and the televised horrors of Vietnam. Just three years before Halloween, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws debuted, spurring a number of readings that linked the killer shark to Watergate, Kent State, and Vietnam. The next year, the uncertain motivations of Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver forced moviegoers to consider what might have inspired his warped fixations and ultimate violence, with theories claiming he personified racism, religious vengeance, and postwar trauma. Other titles from A Clockwork Orange (1971), The French Connection (1971), Deliverance (1972), Chinatown (1974), The Conversation (1974), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), Nashville (1975), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), The Deer Hunter (1978), Apocalypse Now (1979), and Being There (1979) robbed moviegoers of tidy solutions to complex problems. They acknowledged the failure of American political and social institutions, and they defied any assurances promised by a rational world. Halloween arrived at the end of the decade, in 1978, and embodied American uncertainty in such a way that terrified audiences, and it still maintains the capacity to terrify modern viewers.

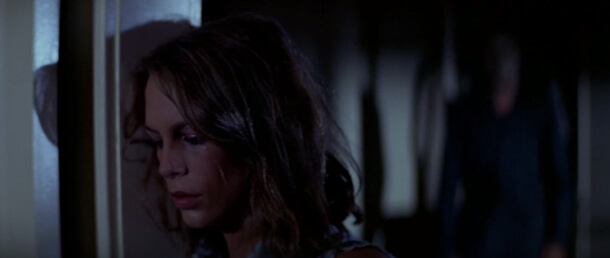

Michael Myers is the epitome of 1970s uncertainty. He is the unknown, the inexplicable. He has no motivations, no reasons for killing. His methods are just as mysterious. A voyeur, he watches from a distance, studying his prey. Even when the camera takes another’s perspective, it’s so that the viewer can feel like he’s watching us. And when he attacks, he does so at a measured pace from which his soon-to-be victims run hopelessly away. He seems to be made of flesh and blood, but he’s shot six times at close range in the end and survives somehow. Michael Myers penetrates every mechanism designed to keep the average American safe. He has escaped the mental hospital that kept him locked away. So-called specialists could not define his sickness. The law is helpless to stop him. The parents who should be protecting their children are mysteriously absent. And so, the children become the prey of a monster that, quite simply, defies any traditional conception or understanding. He is, as the schoolboy Tommy Doyle (Brian Andrews) remarks, “the Boogeyman”—an unstoppable force that cannot be explained with logic, rationality, or science. In folklore that goes back hundreds of years and spreads across dozens of cultures, Boogeyman myths often centered around an evil, clandestine figure that snatches away misbehaving children. Michael Myers is a bedtime story that children are assured doesn’t exist—except, he does. And yet, throughout the film, it’s almost as though the characters cannot see him, an anomaly furthered by his mask amid the bustling All Hallows’ Eve festivities in Haddonfield, Illinois. He seems to slip right past in the background of several scenes, watching characters who rarely take notice that they’re being watched. As J.P. Tellote observes in his essay on the movie, “What Carpenter seems intent on demonstrating is how consistently our perceptions and understandings of the world around us fall short.”

Michael Myers is the epitome of 1970s uncertainty. He is the unknown, the inexplicable. He has no motivations, no reasons for killing. His methods are just as mysterious. A voyeur, he watches from a distance, studying his prey. Even when the camera takes another’s perspective, it’s so that the viewer can feel like he’s watching us. And when he attacks, he does so at a measured pace from which his soon-to-be victims run hopelessly away. He seems to be made of flesh and blood, but he’s shot six times at close range in the end and survives somehow. Michael Myers penetrates every mechanism designed to keep the average American safe. He has escaped the mental hospital that kept him locked away. So-called specialists could not define his sickness. The law is helpless to stop him. The parents who should be protecting their children are mysteriously absent. And so, the children become the prey of a monster that, quite simply, defies any traditional conception or understanding. He is, as the schoolboy Tommy Doyle (Brian Andrews) remarks, “the Boogeyman”—an unstoppable force that cannot be explained with logic, rationality, or science. In folklore that goes back hundreds of years and spreads across dozens of cultures, Boogeyman myths often centered around an evil, clandestine figure that snatches away misbehaving children. Michael Myers is a bedtime story that children are assured doesn’t exist—except, he does. And yet, throughout the film, it’s almost as though the characters cannot see him, an anomaly furthered by his mask amid the bustling All Hallows’ Eve festivities in Haddonfield, Illinois. He seems to slip right past in the background of several scenes, watching characters who rarely take notice that they’re being watched. As J.P. Tellote observes in his essay on the movie, “What Carpenter seems intent on demonstrating is how consistently our perceptions and understandings of the world around us fall short.”

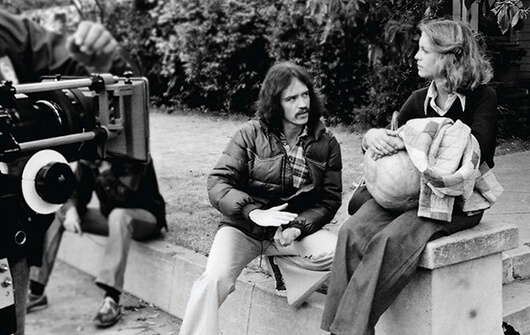

Whether the filmmakers knew they were creating a timeless monster is debatable. After the modest success of Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), producer Irwin Yablans set up a production company called Compass International Ltd., and he offered Carpenter an opportunity to make The Babysitter Murders, which, as the title suggests, was about babysitters who are murdered by a masked killer. Carpenter agreed, not because the idea of a guy killing babysitters interested him, but because Yablans wanted it to take place on Halloween night. Carpenter wanted to return the holiday from a family-friendly night where children receive candy into a warning, harkening back to the Samhain, the harvest period when ancient Celts believed the ghosts of the dead returned to Earth. With that in mind, Carpenter would co-write with his producer, Debra Hill, transforming the movie’s killer into a Boogeyman of sorts. Moreover, he had a few essential demands before he agreed to the project: He wanted complete autonomy and creative control, with the promise from Yablans and the financier, Moustapha Akkad, that they wouldn’t interfere with his progress. Additionally, Carpenter wanted to write the score to the $300,000 production, now retitled Halloween. And after Yablans and Akkad agreed to his terms, Carpenter and Hill proceeded to write the scenario in just 10 days. Hill wrote the scenes with the cast of teenage girls, while Carpenter focused on the escaped mental patient, Michael Myers, and his obsessed pursuer, Dr. Sam Loomis (Donald Pleasance), named after John Gavin’s character in Psycho (1960). When Carpenter referenced the killer in the screenplay, however, he called it The Shape.

Shot in just 22 days, with Pasadena, California making an auspicious appearance as Haddonfield, Halloween completed production on budget and on schedule. After assembling his movie in the editing room, the director screened the initial cut without music for various studio executives. They unanimously told him it wasn’t scary. Only after taking a few days to write and add the musical score did the same executives proclaim that Halloween terrified them. Carpenter was assured he had a hit. His score is haunting and iconic. It was composed in complex time, a five-four meter that sounds odd to Western ears accustomed to the commonly used four-four meter of simple time. Nevertheless, it is perhaps the best-known score in the horror genre next to Bernard Herrmann’s slashing strings in Psycho. After the movie’s debut in Carpenter’s hometown of Bowling Green, Kentucky on October 25, 1978, Halloween branched out to the coastal cities, reaching critics and audiences over the coming year. Vincent Canby in The New York Times wrote it was “simple but it is not simple-minded. It is admirably functional and to the point.” Newsweek critic David Ansen was more enthusiastic when he wrote, “Nasty, voyeuristic, relentless, it aims at nothing but to scare the hell out of you.” By the end of its initial theatrical run, the movie grossed more than $50 million and then earned another $30 million in subsequent re-releases. Before being edged out in 1990 by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Halloween held a standing as the most profitable independent feature of its time.

Shot in just 22 days, with Pasadena, California making an auspicious appearance as Haddonfield, Halloween completed production on budget and on schedule. After assembling his movie in the editing room, the director screened the initial cut without music for various studio executives. They unanimously told him it wasn’t scary. Only after taking a few days to write and add the musical score did the same executives proclaim that Halloween terrified them. Carpenter was assured he had a hit. His score is haunting and iconic. It was composed in complex time, a five-four meter that sounds odd to Western ears accustomed to the commonly used four-four meter of simple time. Nevertheless, it is perhaps the best-known score in the horror genre next to Bernard Herrmann’s slashing strings in Psycho. After the movie’s debut in Carpenter’s hometown of Bowling Green, Kentucky on October 25, 1978, Halloween branched out to the coastal cities, reaching critics and audiences over the coming year. Vincent Canby in The New York Times wrote it was “simple but it is not simple-minded. It is admirably functional and to the point.” Newsweek critic David Ansen was more enthusiastic when he wrote, “Nasty, voyeuristic, relentless, it aims at nothing but to scare the hell out of you.” By the end of its initial theatrical run, the movie grossed more than $50 million and then earned another $30 million in subsequent re-releases. Before being edged out in 1990 by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Halloween held a standing as the most profitable independent feature of its time.

Halloween’s success spawned countless imitators, each made with low budgets, low brows, and variations on the movie’s formula in an attempt to repeat its success. Many of them paired a masked killer with a holiday, used a subjective camera to approximate a voyeur, and distinguished their killers by their weapon of choice. Although Black Christmas (1974) had a similar setup before Halloween, the huge payday of Carpenter’s movie inspired copycats: Friday the 13th (1980), Mother’s Day (1980), My Bloody Valentine (1981), New Year’s Evil (1982), Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984), and others appeared throughout the 1980s. Countless more adopted the slasher components of Michael Myers without the holiday flourish, such as Boogeyman (1980), Alone in the Dark (1982), Slumber Party Massacre (1983), Pieces (1983), and Sleepaway Camp (1983), to name a few—there are countless more. Many of the specific themes and techniques in Halloween had been established elsewhere as well. For instance, the theme of a child who murders was explored in 1969’s The Mad Room; kitchen knife killings appeared in Psycho; and the subjective camera played a major role in Jaws, occupying the shark’s point-of-view in lieu of a functioning underwater animatronic fish.

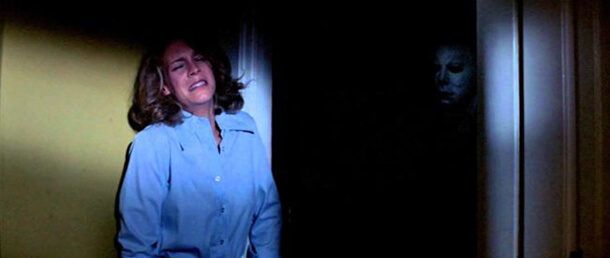

Halloween stands apart from its followers by the simplicity of its execution and the naturalism of its characters. The methodology to Carpenter’s scares in Halloween is similar to that of Alfred Hitchcock, who famously described suspense as something the audience is aware of but the film’s characters are not. Hitchcock offered an example: Two people seated at a table have a casual conversation. Just then, the camera moves down to observe a bomb with a ticking clock under the table. As the people continue to talk about nothing important at all, their lives hanging in the balance, the audience is driven mad with anticipation, waiting for the timer to run out and the bomb to detonate. In this scenario, it’s not the explosion, it’s the waiting. The same is true of Carpenter’s approach on Halloween. His long takes using the Panaglide camera—an alternate form of Steadicam, which the director learned to use on Someone’s Watching Me!, the TV-movie he shot before Halloween—unfold with leisurely foreboding. This allows for a perfect use of the subjective camera that floats along, without the shuddering of a handheld camera. Michael follows and stalks his teenage prey around corners, through interiors, or up the stairs in smooth, unsettling movements. He always seems to be lurking nearby or prowling about outside of every scene, enhancing the suspense from moment to moment. An uneasy feeling permeates in the audience, as we know Michael is on his way, but Laurie and her friends do not. We watch through his eyes, uncomfortably put in the voyeur-killer’s perspective.

Halloween stands apart from its followers by the simplicity of its execution and the naturalism of its characters. The methodology to Carpenter’s scares in Halloween is similar to that of Alfred Hitchcock, who famously described suspense as something the audience is aware of but the film’s characters are not. Hitchcock offered an example: Two people seated at a table have a casual conversation. Just then, the camera moves down to observe a bomb with a ticking clock under the table. As the people continue to talk about nothing important at all, their lives hanging in the balance, the audience is driven mad with anticipation, waiting for the timer to run out and the bomb to detonate. In this scenario, it’s not the explosion, it’s the waiting. The same is true of Carpenter’s approach on Halloween. His long takes using the Panaglide camera—an alternate form of Steadicam, which the director learned to use on Someone’s Watching Me!, the TV-movie he shot before Halloween—unfold with leisurely foreboding. This allows for a perfect use of the subjective camera that floats along, without the shuddering of a handheld camera. Michael follows and stalks his teenage prey around corners, through interiors, or up the stairs in smooth, unsettling movements. He always seems to be lurking nearby or prowling about outside of every scene, enhancing the suspense from moment to moment. An uneasy feeling permeates in the audience, as we know Michael is on his way, but Laurie and her friends do not. We watch through his eyes, uncomfortably put in the voyeur-killer’s perspective.

Besides the anxious, disquieting use of slow-burning suspense, Carpenter enhances our fear through his use of space, toying with our claustrophobia as the walls seem to close in on his convincing characters. Early scenes in Haddonfield take place in the open air, on the leaf-strewn autumn streets of an average American suburb. The broad widescreen turns them into specks in the frame’s void. The bookish Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis), her sarcastic friend Annie (Nancy Kyes), and the bubbleheaded Lynda (P.J. Soles) talk about boys and their plans for the evening, joking about their sexual escapades, or lack thereof. They drive around the neighborhood and find Annie’s father, Sheriff Brackett (Charles Cyphers), who investigates the hardware store break-in where Michael has stolen a mask—famously, a mask of James T. Kirk from Star Trek painted white. Tommy heads home from school, spooked by bullies who implanted his fear that “The Boogeyman is going to get you!” Night comes, and the scenes move inside of the few houses where Laurie babysits Tommy, Annie babysits Lindsey (Kyle Richards), and Lynda beds her boyfriend, Bob (John Michael Graham). Spaces narrow as the film leans into each killing. Annie goes from being trapped in a window to a cramped automobile where she’s strangled to death. Bob dies in the kitchen before Lynda gets it in the bedroom. Laurie, meanwhile, hides from Michael in a closet, the most restricted space of all. Carpenter ratchets the tension by gradually closing in on the characters, and thus the viewer, leaving us with nowhere to run. But then, in the final scenes that search the neighborhood for Michael—scenes that should release us from the movie’s prison of cramped spaces—Carpenter suggests that the evil remains at large.

As for the meaning of these events, there are theories abound: Author John Kenneth Muir speculates that Halloween “deconstructs our technological, contemporary world” through the failure of modern science, as represented by Dr. Loomis. Not even modern psychology, sociology, medicine, or any of the complex mental diseases described in psychological manuals can explain away Michael Myers. His condition resists diagnosis. He’s not the product of an abusive upbringing, nor does he act from a genetic predisposition to violence, nor is he following the orders of a Satanic cult or possessive demon. As Loomis explains, “I met him 15 years ago. I was told there was nothing left. No reason, no conscience, no understanding in even the most rudimentary sense of life or death, of good or evil, right or wrong. I met this six-year-old child with this blank, pale, emotionless face, and… the blackest eyes. The Devil’s eyes. I spent eight years trying to reach him, and then another seven trying to keep him locked up, because I realized that what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply evil.” It’s a theme that echoes throughout the picture. Michael is an unstoppable evil who, in the final scene, disappears after taking several bullets from Loomis’ gun and falling, seemingly to his death, on the lawn below. But the final twist of Halloween—where Carpenter shows the yard empty, and Michael gone, followed by a montage that searches the Doyle house and the neighborhood for signs of the masked killer, all set to the sound of Michael’s heavy breathing on the soundtrack—implies with a chilling finality that the evil is still out there.

As for the meaning of these events, there are theories abound: Author John Kenneth Muir speculates that Halloween “deconstructs our technological, contemporary world” through the failure of modern science, as represented by Dr. Loomis. Not even modern psychology, sociology, medicine, or any of the complex mental diseases described in psychological manuals can explain away Michael Myers. His condition resists diagnosis. He’s not the product of an abusive upbringing, nor does he act from a genetic predisposition to violence, nor is he following the orders of a Satanic cult or possessive demon. As Loomis explains, “I met him 15 years ago. I was told there was nothing left. No reason, no conscience, no understanding in even the most rudimentary sense of life or death, of good or evil, right or wrong. I met this six-year-old child with this blank, pale, emotionless face, and… the blackest eyes. The Devil’s eyes. I spent eight years trying to reach him, and then another seven trying to keep him locked up, because I realized that what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply evil.” It’s a theme that echoes throughout the picture. Michael is an unstoppable evil who, in the final scene, disappears after taking several bullets from Loomis’ gun and falling, seemingly to his death, on the lawn below. But the final twist of Halloween—where Carpenter shows the yard empty, and Michael gone, followed by a montage that searches the Doyle house and the neighborhood for signs of the masked killer, all set to the sound of Michael’s heavy breathing on the soundtrack—implies with a chilling finality that the evil is still out there.

Since Michael Myers cannot be pinpointed, his indefinability has led to many explanations, most of them well-argued if subject to holes in their evidence. Most commonly, Halloween has been accused of enforcing a moral justice against women who indulge in their sexual impulses. Michael seems to punish women, namely his sister Judith (Sandy Johnson), Annie, and Lynda, for their sexuality and nudity. His female victims each appear nude and, having been spied on by Michael, meet their demise shortly after exposing themselves. Michael kills most of his victims in bedrooms, or commits his murders as his victims plan for, or have just completed, a sexual encounter. Sexual liberty seems to enrage Michael, a motivation that stems back to his childhood killing of his sister, whose gravestone he situates on a bed where he has arranged Annie’s lifeless corpse in an odd commemoration. Whatever the reasons, Michael is driven by an aversion to sexuality and nudity, particularly in women. This distorted, albeit tempting argument ignores that Michael also kills two men and two dogs in the movie. It also begs the question of why, if Michael is obsessed with punishing sexually active women, does he focus so intently on Laurie, who is nothing like her friends or Michael’s sister? The simple answer could be that Laurie is the first teen Michael sees upon his return to his childhood home in Haddonfield, where, early in the day, Laurie visits to drop off a key for her father, a realtor. She’s roughly Michael’s sister’s age during the murder, which could have sparked an association. Furthermore, Michael’s motivation could be analogous to Jason Voorhees from the Friday the 13th franchise, who gets revenge on camp counselors that were having sex while he was drowning—in both cases, a child is neglected in favor of adolescent sex. Then again, Michael survived despite his sister’s intercourse.

In another argument, Robin Wood published an article in Film Comment called “The Return of the Repressed” just two months before Halloween hit theaters, discussing films such as Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Wood argues that the era of horror films emerging in the 1970s signify “the sense of a civilization condemning itself, through its popular culture, the ultimate disintegration, and ambivalently celebrating the fact.” Wood’s article feeds the common interpretation of Halloween and subsequent slasher movies that condemn sexuality, turning it into an act policed by the movie’s resident killer. The masked or deformed killer, deeply repressed, punishes those horny teens who are sexually active, whereas the virginal heroine, often the final girl, seemingly survives based on her chastity. Moreover, as the religious right in American culture began to emerge in the 1970s with support from fundamentalist Christians and eventually Ronald Reagan’s presidency, they perceived an increase in deviant behavior and a decline in family unity in the wake of the sexual revolution, women’s liberation, and the search for self among Generation Me. With the pressure of a patriarchally enforced Christian morality lingering in the cultural consciousness, the audience of horror films during this era celebrates, rather than mourns, the deaths of the teen victims whose sexuality make them prey to a killer motivated to punish the wicked—using a phallic knife as his weapon of choice. Killers like Leatherface or Michael Myers, then, serve as extensions of a vengeful God, wiping out sinners with biblical might.

In another argument, Robin Wood published an article in Film Comment called “The Return of the Repressed” just two months before Halloween hit theaters, discussing films such as Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Wood argues that the era of horror films emerging in the 1970s signify “the sense of a civilization condemning itself, through its popular culture, the ultimate disintegration, and ambivalently celebrating the fact.” Wood’s article feeds the common interpretation of Halloween and subsequent slasher movies that condemn sexuality, turning it into an act policed by the movie’s resident killer. The masked or deformed killer, deeply repressed, punishes those horny teens who are sexually active, whereas the virginal heroine, often the final girl, seemingly survives based on her chastity. Moreover, as the religious right in American culture began to emerge in the 1970s with support from fundamentalist Christians and eventually Ronald Reagan’s presidency, they perceived an increase in deviant behavior and a decline in family unity in the wake of the sexual revolution, women’s liberation, and the search for self among Generation Me. With the pressure of a patriarchally enforced Christian morality lingering in the cultural consciousness, the audience of horror films during this era celebrates, rather than mourns, the deaths of the teen victims whose sexuality make them prey to a killer motivated to punish the wicked—using a phallic knife as his weapon of choice. Killers like Leatherface or Michael Myers, then, serve as extensions of a vengeful God, wiping out sinners with biblical might.

Carpenter has dismissed theories about a moral killer who represents a cultural phenomenon, suggesting instead that Michael is motivated by “an Oedipal or incestual thing,” he told Gilles Boulenger. In the opening scene, the young Myers boy watches his sister Judith from outside through the window as she and her boyfriend go upstairs. Her bedroom light turns off, the implication clear enough to cause a pang on the score, perhaps a reflection of the jarring discomfort Michael feels toward sexuality. Shortly thereafter, Michael makes his way inside. The boyfriend leaves, quickly satisfied. Michael puts on his Halloween clown mask and creeps upstairs to spy on his sister’s post-coital hair-brushing. And then he kills her. “Part of what he’s doing is getting vengeance on her,” said Carpenter, as though every killing to follow was just another Judith in Michael’s mind. However, Carpenter’s explanation does not satisfactorily justify why this version of Michael, motivated by such basic Freudian drives, would be seen as a source of evil by Dr. Loomis. Carpenter’s explanation extends to Laurie Strode as well. He suggests that a sexually frustrated Laurie takes control of phallic objects (a knitting needle, a bent hanger, and Michael’s own knife) and stabs Michael because she, too, is repressed, and therefore lashing out. Many scholars have noted the connection between Laurie Strode and Michael Myers, as the latter watches the former from behind on her way home, as if affectionately recognizing a fellow repressed. According to scholar Vera Dika, Laurie’s battle with Michael is a symbol for her own struggle with sexuality and desire, and it almost gets the best of her. However, the argument that Halloween is somehow about Laurie taking control of her unconscious impulses is waylaid when Loomis rescues her at the last moment.

Others have suggested a connection through an intangible, mystical element of fate as Laurie’s latent superstition and Michael’s supernatural force collide. The theme is established in class, when Laurie answers her teacher’s question about fate: “Samuels felt that fate was like a natural element, like earth, air, fire, and water.” The teacher’s voice replies, “That’s right, Samuels definitely personified fate.” Michael seems to be that personification, confirming Tommy Doyle’s worst nightmares and shattering Laurie’s illusions of a rational world. Laurie doesn’t believe in such things, or at least she doesn’t think she believes in them. After getting the heebie-jeebies from spotting Michael in the late afternoon, Laurie hears screams. She’s relieved to discover it’s just trick-or-treaters. “I thought you outgrew superstitions,” she remarks to herself. Later that evening, when Tommy sees Michael out the window and claims he’s seen the Boogeyman, she explains to him, “It’s all make-believe.” Not until Laurie is confronted with Michael, and witnesses his apparent invulnerability to multiple stabbings, does she cry to Loomis, “Was that the Boogeyman?” Loomis cannot deny it. “As a matter of fact, it was.” In this reading, it’s almost as though Michael appears simply to prove wrong those who doubt the existence of the supernatural. Carpenter’s films often concern cynics and doubters being confronted with the unknown as part of a fated plan—see Big Trouble in Little China (1986), Prince of Darkness (1987), They Live (1988), or In the Mouth of Madness (1994).

Others have suggested a connection through an intangible, mystical element of fate as Laurie’s latent superstition and Michael’s supernatural force collide. The theme is established in class, when Laurie answers her teacher’s question about fate: “Samuels felt that fate was like a natural element, like earth, air, fire, and water.” The teacher’s voice replies, “That’s right, Samuels definitely personified fate.” Michael seems to be that personification, confirming Tommy Doyle’s worst nightmares and shattering Laurie’s illusions of a rational world. Laurie doesn’t believe in such things, or at least she doesn’t think she believes in them. After getting the heebie-jeebies from spotting Michael in the late afternoon, Laurie hears screams. She’s relieved to discover it’s just trick-or-treaters. “I thought you outgrew superstitions,” she remarks to herself. Later that evening, when Tommy sees Michael out the window and claims he’s seen the Boogeyman, she explains to him, “It’s all make-believe.” Not until Laurie is confronted with Michael, and witnesses his apparent invulnerability to multiple stabbings, does she cry to Loomis, “Was that the Boogeyman?” Loomis cannot deny it. “As a matter of fact, it was.” In this reading, it’s almost as though Michael appears simply to prove wrong those who doubt the existence of the supernatural. Carpenter’s films often concern cynics and doubters being confronted with the unknown as part of a fated plan—see Big Trouble in Little China (1986), Prince of Darkness (1987), They Live (1988), or In the Mouth of Madness (1994).

At other times, it’s almost as though an evil force inside of Michael controls him, another entity or part of Michael that remains separate, remote, or even otherworldly. Perhaps this is The Shape of the Carpenter-Hill screenplay, whereas Michael, suppressed by evil, can do nothing more than quietly observe his body’s actions from within. Consider an odd moment from the opening sequence when, in a point-of-view shot, Michael creeps upstairs to kill his sister. As he brings the knife down on her repeatedly, the subjective camera looks away at the knife in his hand, as if in disbelief. Carpenter, along with many critics and scholars, has explained this shot as a filmmaking necessity—a way for the director to avoid needing an expensive practical effect to show the stabbing in detail. Instead, he relied on an awkward moment where Michael looks away at his own hand motions, while the actress playing Judith poured fake blood on herself to appear dead when the camera returned to her. But what if Michael has something inside of him that controls his body and allows him to emerge at rare times? Is this shot evidence of a possessed Michael beholding his body with powerlessness and disbelief? Elsewhere, watch how Michael sometimes reflects on victims’ bodies or pauses to deliberate; in those brief moments, perhaps this is Michael regaining some control over the source of evil—The Shape—that propels him. In any case, the theories remain boundless and inconclusive.

Interpretations aside, several sequels and remakes since the original have sought to demystify the very thing that made Halloween so powerful, its unknowability. Halloween II (1981) explained away Michael’s motivations by introducing the absurd idea that Laurie is his sister, born after Michael’s institutionalization and given up for adoption—a detail he could not have known about. In Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers (1988), Laurie dies offscreen and leaves behind an orphaned daughter, Michael’s niece, Jamie, who, in addition to becoming his target, inherits her uncle’s psychopathy. Both Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers (1989) and Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers (1995) follow Dr. Loomis’ continued mission to stop Michael, while protecting Jamie and the grown-up Tommy Doyle. When the franchise rights passed from Akkad to Miramax, Halloween H20: 20 Years Later (1998) revived Laurie Strode for a final battle against Michael, except he was brought back to life again in the throwaway sequel, Halloween: Resurrection (2002). In 2007 and 2009, Rob Zombie’s remakes Halloween and Halloween 2 sought to explain Michael’s propensity for murder by exploring his abusive and maniacal upbringing in a broken home, linking Michael Myers to a breed of American serial killers. None of these films seemed to understand that the strength of Carpenter’s original lies in the unknown, inexplicable, and mysterious.

Interpretations aside, several sequels and remakes since the original have sought to demystify the very thing that made Halloween so powerful, its unknowability. Halloween II (1981) explained away Michael’s motivations by introducing the absurd idea that Laurie is his sister, born after Michael’s institutionalization and given up for adoption—a detail he could not have known about. In Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers (1988), Laurie dies offscreen and leaves behind an orphaned daughter, Michael’s niece, Jamie, who, in addition to becoming his target, inherits her uncle’s psychopathy. Both Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers (1989) and Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers (1995) follow Dr. Loomis’ continued mission to stop Michael, while protecting Jamie and the grown-up Tommy Doyle. When the franchise rights passed from Akkad to Miramax, Halloween H20: 20 Years Later (1998) revived Laurie Strode for a final battle against Michael, except he was brought back to life again in the throwaway sequel, Halloween: Resurrection (2002). In 2007 and 2009, Rob Zombie’s remakes Halloween and Halloween 2 sought to explain Michael’s propensity for murder by exploring his abusive and maniacal upbringing in a broken home, linking Michael Myers to a breed of American serial killers. None of these films seemed to understand that the strength of Carpenter’s original lies in the unknown, inexplicable, and mysterious.

Halloween turned John Carpenter into a horror legend, and besides launching his career as a filmmaker, it established, for better or worse, a lasting franchise and the slasher subgenre. More than Carpenter’s eerie synth score, the quirky characters, the charming performances, or the chills involved in a masked killer stalking his prey, the movie’s elusiveness is what draw us back again and again—unlike later sequels or remakes that attempt to introduce a new, marketable wrinkle that provides answers to Michael Myers’ backstory and, as a result, demystifies the haunting authority of the original. The power of Halloween resides in Carpenter’s original conception of Michael Myers as The Shape, a dark and indecipherable force that betrays our understanding of the natural world. The Shape is the Boogeyman, a source of evil whose origins and connections to Laurie Strode remain debatable, perhaps unknowable within the context of this single movie, as evidenced by the endless theories that attempt to explain away Michael Myers. None of them completely satisfy every mysterious aspect about the movie, and so the fact remains, we don’t know what The Shape is. That’s what makes it scary. That’s what makes it endure.

Bibliography:

Boulenger, Gilles. John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness. Spakenburg: H.O.M. Vision, 2002.

Cumbow, Robert C. Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc.; Second Edition, 2000.

Dika, Vera. Games of Terror: Halloween, Friday the 13th and the Films of the Stalker Cycle. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1990.

Muir, John Kenneth. The Films of John Carpenter. Jefferson: McFarland, 2000.

Telotte, J.P. “Through a Pumpkin’s Eye: The Reflexive Nature of Horror.” American Horror: Essays on the Modern American Horror Film. Edited by Gregory A. Waller. McFarland, 1986.

Wood, Robin. “Return of the Repressed.” Film Comment, vol. 14, no. 4, 1978, pp. 24–32.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review