The Definitives

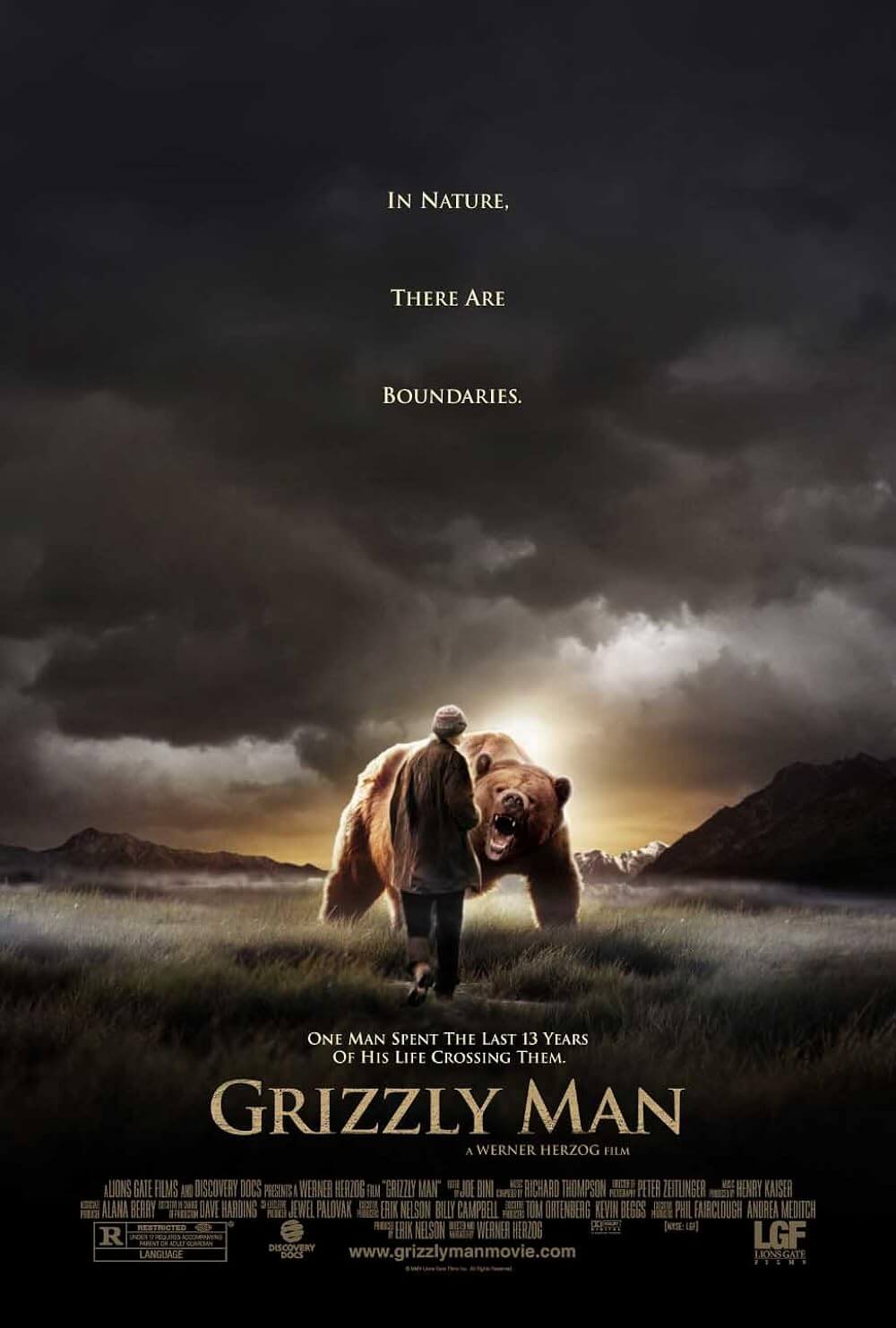

Grizzly Man

Essay by Brian Eggert |

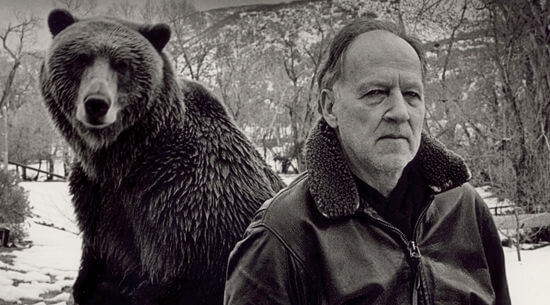

Environmentalist and self-appointed bear savior Timothy Treadwell shot most of the footage in Grizzly Man, yet the film is perhaps the finest and most characteristic of Werner Herzog’s documentaries. Treadwell remains a consummate Herzogian subject, someone who confronted the wilderness to discover a measure of personal truth but was overcome by the sublimity of Nature. Herzog believes Nature is chaotic and brutal. When subjects from both his fiction and nonfiction films confront or attempt to conquer Nature to achieve their dreams or desires, he anticipates the inevitable human-Nature conflict and finds himself drawn to the encounter’s resultant truth. Herzog’s humanist exploration of Nature and truth in his films manifests through his contemplative narration, expressive formal choices, and appreciation for the cinematic quality of the natural world. Such apparent subjectivity is an active choice on his part; he rejects documentaries made in the cinéma vérité style for their lack of personal truth and poetic license. As a documentarian, Herzog is not interested in fact; he attempts to understand the cruel truth about Nature, and yet he also seems to know that understanding Nature is impossible. Grizzly Man reveals Herzog’s ambition as a documentarian through his depiction and desire to understand Treadwell, a man who looked to Nature for comfort, yet ultimately became a victim of the sublime.

For the summer months over thirteen years, Treadwell camped in Katmai National Park and Preserve, Alaska, hiding from authorities on a personal mission to protect the resident population of grizzly bears better than the Park Service could, he believed. During that time, Treadwell shot nearly 100 hours of gorgeous wildlife footage, earning notoriety among environmentalists. Alongside friend Jewel Palovak, he also founded a bear conservationist group called Grizzly People, and during his off-season taught schoolchildren about his experiences. A social outcast drawn to the wild, Treadwell projected onto his bear “friends,” anthropomorphizing them. He gave them names like Mr. Chocolate or Freckles to create bonds that, in the end, did not exist. Treadwell also earned some minor celebrity with appearances on Late Night with David Letterman in 2001 and 2002. The talk show host asked, “Is it going to happen that one day we read a news article about you being eaten by one of these bears?” Letterman’s question anticipated the events of Treadwell’s 2003 visit, when he and girlfriend Amie Huguenard were killed and eaten by a rogue bear. Palovak granted Herzog access to Treadwell’s footage. The German director investigated the recordings and found uncommonly beautiful images of the Alaskan wildlife, but also evidence of a disturbed individual who, as Herzog noted, saw humanity as his enemy: “It is clear to me that the Park Service is not Treadwell’s real enemy. There’s a larger, more implacable adversary out there: The people’s world and civilization.” Grizzly Man combines Treadwell’s footage with Herzog’s interviews and commentary, resulting in a film that portrays Treadwell’s story as a tale of a man who, in the director’s view, failed to understand and respect the sublimity of Nature.

Because Herzog’s approach relies so heavily on his personal perspective to inform his assessment of Treadwell, understanding the director is tantamount to understanding Grizzly Man, at least in part. Born in Munich, Germany, in 1941, Herzog’s passion for filmmaking was immediate: “From the moment I could think independently,” he told film historian Paul Cronin. He also began traveling extensively in his teen years, journeying to places like Alexandria, the Belgian Congo, and dozens of other countries in the years to come. His enthusiasm for film and his wanderlust would combine in his films, as Herzog would soon be known as a filmmaker who traveled to places with the most extreme conditions to get rare footage. At the age of seventeen, he began an independent film production company called Werner Herzog Filmproduktion, and nearly every film in his over sixty directorial credits has been made independently by his company. Herzog’s independence helped instill his presence and personal approach in his work, free of any major studio influence, making each of his films “a Werner Herzog film” in its entirety. From 1962 onward, Herzog would go on to shoot both nonfiction and fiction works, though he does not categorize his efforts; he calls them all “films.”

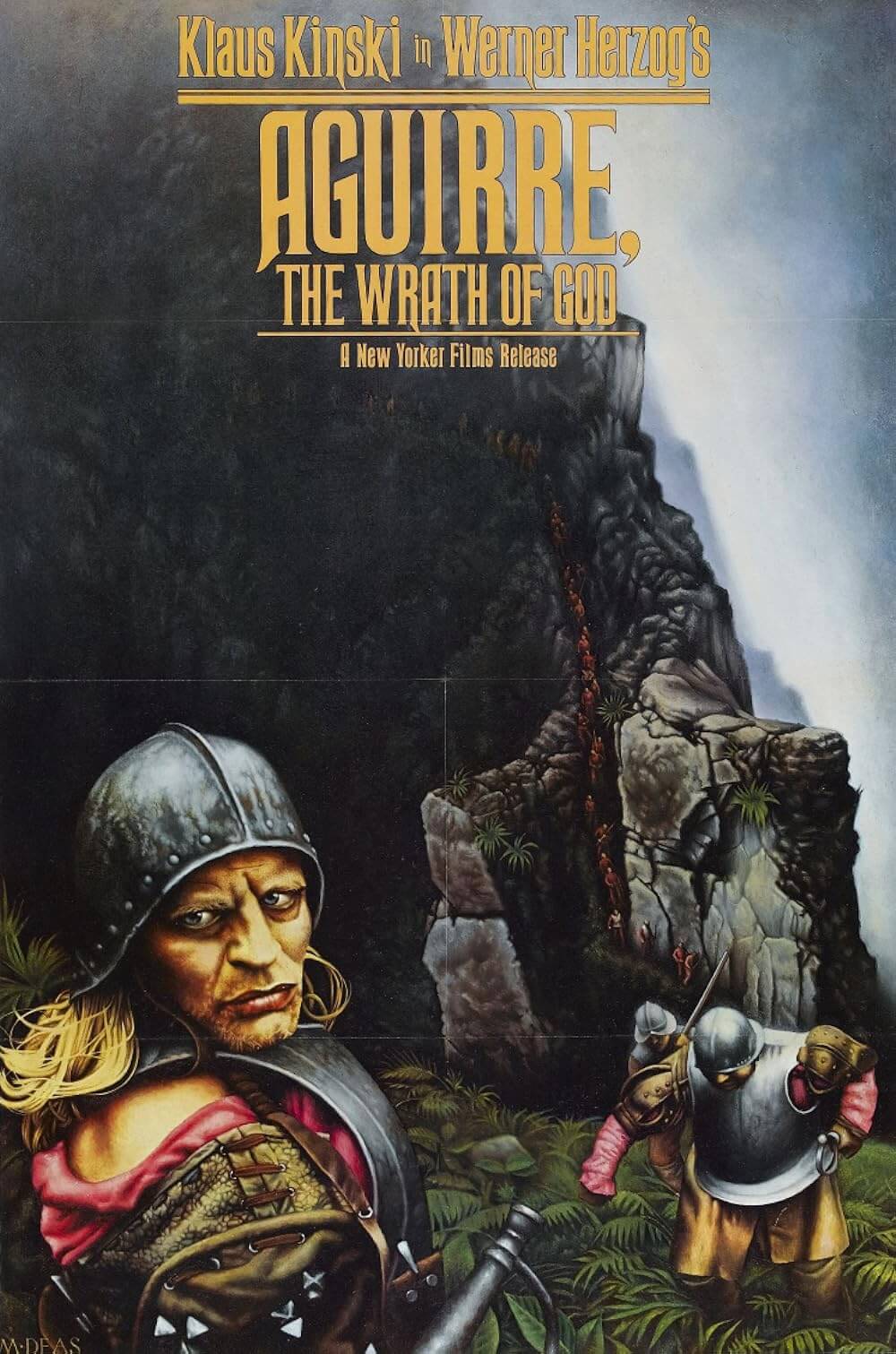

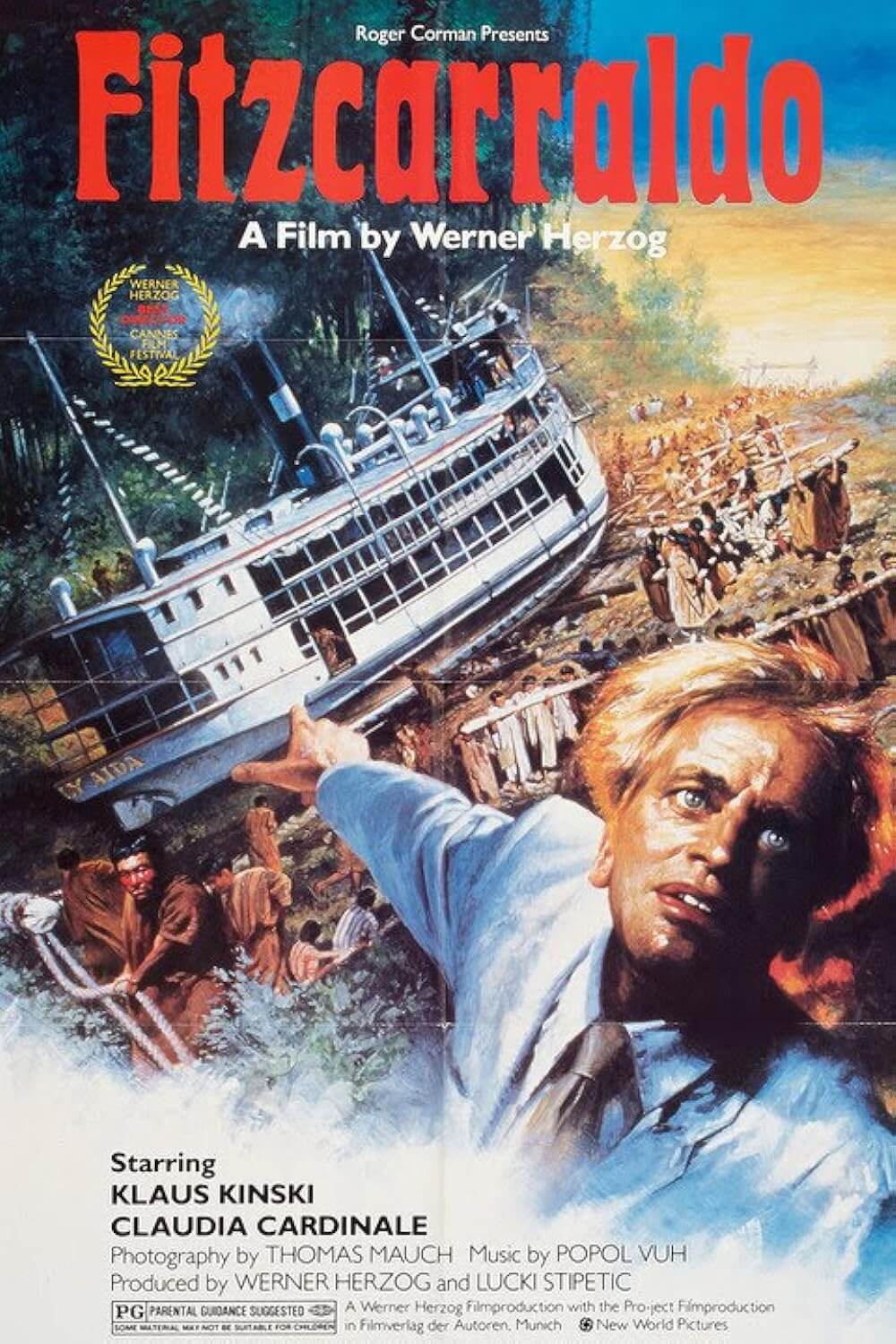

It may be biographical projection to suggest that Herzog developed his particular views on Nature while shooting two of his most celebrated fiction films, Aguirre, The Wrath of God from 1972 and Fitzcarraldo from 1982. He chose to shoot both films on the Peruvian Amazon where he experienced first-hand the harshness of Nature. On Fitzcarraldo, he was followed by Les Blank, who captured the director’s struggle in the 1982 documentary Burden of Dreams. The production of Fitzcarraldo found Herzog trying to hoist a 340-ton steamer boat over a hill between two Amazon tributaries. The task he was trying to film was much more perilous than the true story on which his fictional film was based, and the harsh conditions on the Amazon proved punishing. They shaped Herzog’s enduring view of Nature: “There is some sort of a harmony. It is the harmony of… overwhelming and collective murder.” Ever since shooting both Aguirre, The Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo, Herzog has not been interested in an optimistic view of Nature; rather, he seeks its inherent drama and the personal truth that people discover in their experience. More than factual accounts of people doing amazing things in Nature, Herzog seeks out situations in which his subjects face similarly harsh conditions and arrive at some larger personal understanding.

The director’s reliance on his personal perspective and philosophy about documentaries stands in opposition to the cinéma vérité movement that wanted to record and not interpret reality by maintaining objectivity. Practitioners of cinéma vérité in the 1960s hoped spectators would interpret their raw footage for themselves. They attempted to observe their subjects from a distance, capturing a sense of impartial reality on camera by following their subjects and not trying to control the moment. Cinéma vérité shows; it avoids narration and makes the viewer feel like a participant in a real-world situation. But Herzog’s approach represents a rejection of cinéma vérité, which is not only evident in his films but his remarks against any attempt at objective cinema. In 1999, during his famous Minnesota Declaration, hosted by the Walker Art Center, he outlined his documentary philosophy. Herzog censured cinéma vérité for supposing that “truth can be easily found by taking a camera and trying to be honest.” Herzog derides the cinéma vérité ideology; he associates it with the coldness of facts, which are nothing but “the account’s truth.” He believes that cinema has more in common with poetry than facts, as cinema can “present a number of dimensions much deeper than the level of the so-called truth that we find in cinéma vérité.”

Herzog’s approach involves more commentary and fewer facts than many other documentaries. The misconception around documentaries is that they are always factual or objective; when something appears other than factual, it seems less like a documentary. Nevertheless, there is a creative aspect to documentaries, and Herzog embraces that aspect. His documentaries consist of photographic and video evidence, engaging interviews, and his narration, which often contains his ruminations on the poetic truth of the represented scene. In Grizzly Man, Herzog does not aim for an objective or factual documentary; rather, he investigates Treadwell’s drives by applying his own commentary and exploratory imagery. He relays Treadwell’s footage to the audience through the filter of his subjective perspective, including his views on Nature, truth, and the poetry of the human-Nature struggle. Aside from his reliance on Treadwell’s footage here, Herzog’s approach remains consistent across his documentaries. What the viewer will not find in a Herzog film are devices typically found in fact-based documentaries: data charts, animated maps, or statistics scrolling onscreen; his interviews are rarely stationary, talking head interviews; and he resists reenactments or dramatizations replaying past events.

The search for truth in Herzog’s documentaries begs the question: What is truth? In a culture where facts and truth are disputed, it is important to note that truth is not a fact; truth is a perspective or belief conforming to a personal standard. Nietzsche defined truth as an assemblage of metaphors and illusions created by people to form the world into a form they can understand. Herzog seems to create his truth as Nietzsche describes. He prefers what he calls “the ecstatic truth” to facts because facts normalize and present a standard, whereas truth from Nature illuminates. Moreover, Herzog’s version of truth reinforces the notion that documentaries have an interpretive quality. To be sure, Herzog told Cronin that he operates “through invention, through imagination” in his search for and representation of truth. To Herzog, truth is about feeling and perception, as truth is “a more powerful guiding light than analysis ever will be.” The director’s narration reveals his truth through his commentary on Nature and his human subjects. His monotone yet imaginative (and oft-parodied) voice conveys his truth by providing his understanding of a scene in juxtaposition to his subject. He allows his subjects to function on their terms, but his narration and interjections into a scene also make Herzog a presence in his films, even when he does not appear on-camera.

The search for truth in Herzog’s documentaries begs the question: What is truth? In a culture where facts and truth are disputed, it is important to note that truth is not a fact; truth is a perspective or belief conforming to a personal standard. Nietzsche defined truth as an assemblage of metaphors and illusions created by people to form the world into a form they can understand. Herzog seems to create his truth as Nietzsche describes. He prefers what he calls “the ecstatic truth” to facts because facts normalize and present a standard, whereas truth from Nature illuminates. Moreover, Herzog’s version of truth reinforces the notion that documentaries have an interpretive quality. To be sure, Herzog told Cronin that he operates “through invention, through imagination” in his search for and representation of truth. To Herzog, truth is about feeling and perception, as truth is “a more powerful guiding light than analysis ever will be.” The director’s narration reveals his truth through his commentary on Nature and his human subjects. His monotone yet imaginative (and oft-parodied) voice conveys his truth by providing his understanding of a scene in juxtaposition to his subject. He allows his subjects to function on their terms, but his narration and interjections into a scene also make Herzog a presence in his films, even when he does not appear on-camera.

As suggested, Herzog most often finds truth as he attempts to understand Nature, which he views as a bastion of the sublime: a source of brutal and unsentimental truth. In the Kantian sense, sublime Nature is about awe in the presence of something overwhelmingly powerful, not as some beautiful idyll. Herzog believes Nature demands respect; of course, Nature contains conventional beauty, but the cruel system of Nature also operates in a way that is beautiful in a sublime way. Philosopher Edmund Burke described the sublime’s qualities as “much greater in their effect on the body and mind, than any pleasures which the most learned voluptuary could suggest, or than the liveliest imagination, and the most sound and exquisitely sensible body could enjoy.” As Herzog’s remarks during Burden of Dreams suggest, the filmmaker agrees with Burke’s view of the sublime as a source of “melancholy, dejection, despair” even though it contains “the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.” However horrible and overwhelming the sublime may be, Burke suggests sympathy and understanding through observation can, from “certain distances,” result in the sense of joy. Herzog seems to revel in the joy of exploring the complicated attributes of the sublime, and he acknowledges that Nature, though murderous, contains unquestionable splendor too. “In [Treadwell’s] material lay dormant a story of astonishing beauty and depth,” the director observes.

To represent the sublime and capture truth, Herzog takes an approach that contains an apparent stylization and draws from his openly subjective perspective. Because he resists the straightforwardness of facts that impels cinéma vérité, his style invites and inspires interpretation. “Stylization,” Herzog told Cronin, “means that the images penetrate deeper than the CNN footage ever could.” Filmmakers who follow the observational methods of cinéma vérité believe documentaries should record and not interpret reality, even though their choice of topic and framing amount to subjective choices. But Herzog understands that images, regardless of how much or little they contain subjectivity, help us understand the filmmaker’s conception of the world. Herzog’s images explore; his camera roams and lingers, searching for answers and meaning, probing every scene. His music choices are brooding, often religious choruses and dissonant strings to accompany his visuals. The combination of a searching camera and resounding music is something almost spiritual that reflects Herzog’s search for poetic truth or answers that exist beyond scientific facts. Take the moment when he looks at Treadwell’s footage of the bear that killed him: “What haunts me is that in all the faces of all the bears that Treadwell ever filmed, I discover no kinship, no understanding, no mercy. I see only the overwhelming indifference of nature. To me, there is no such thing as a secret world of the bears, and this blank stare speaks only of a half-bored interest in food.”

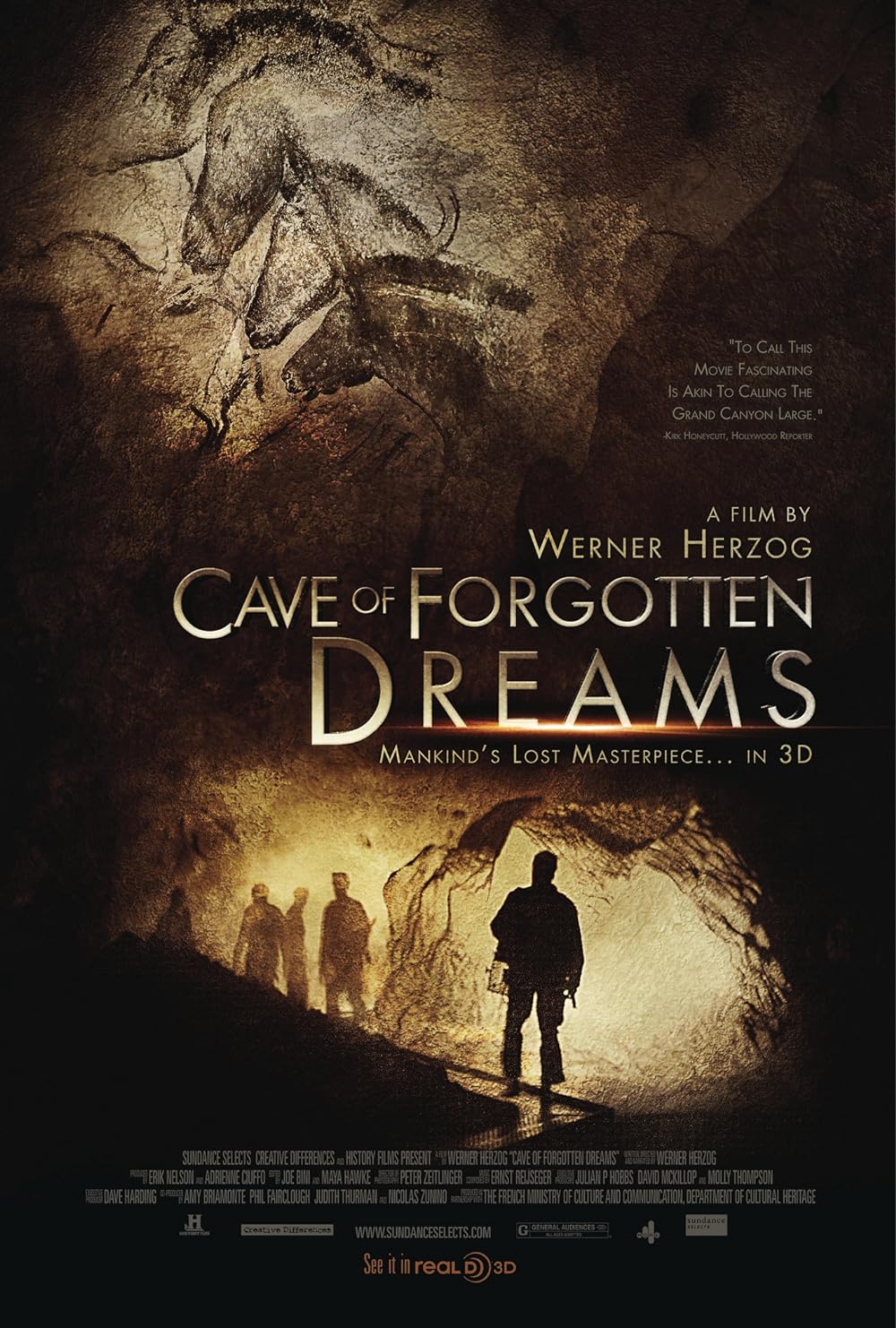

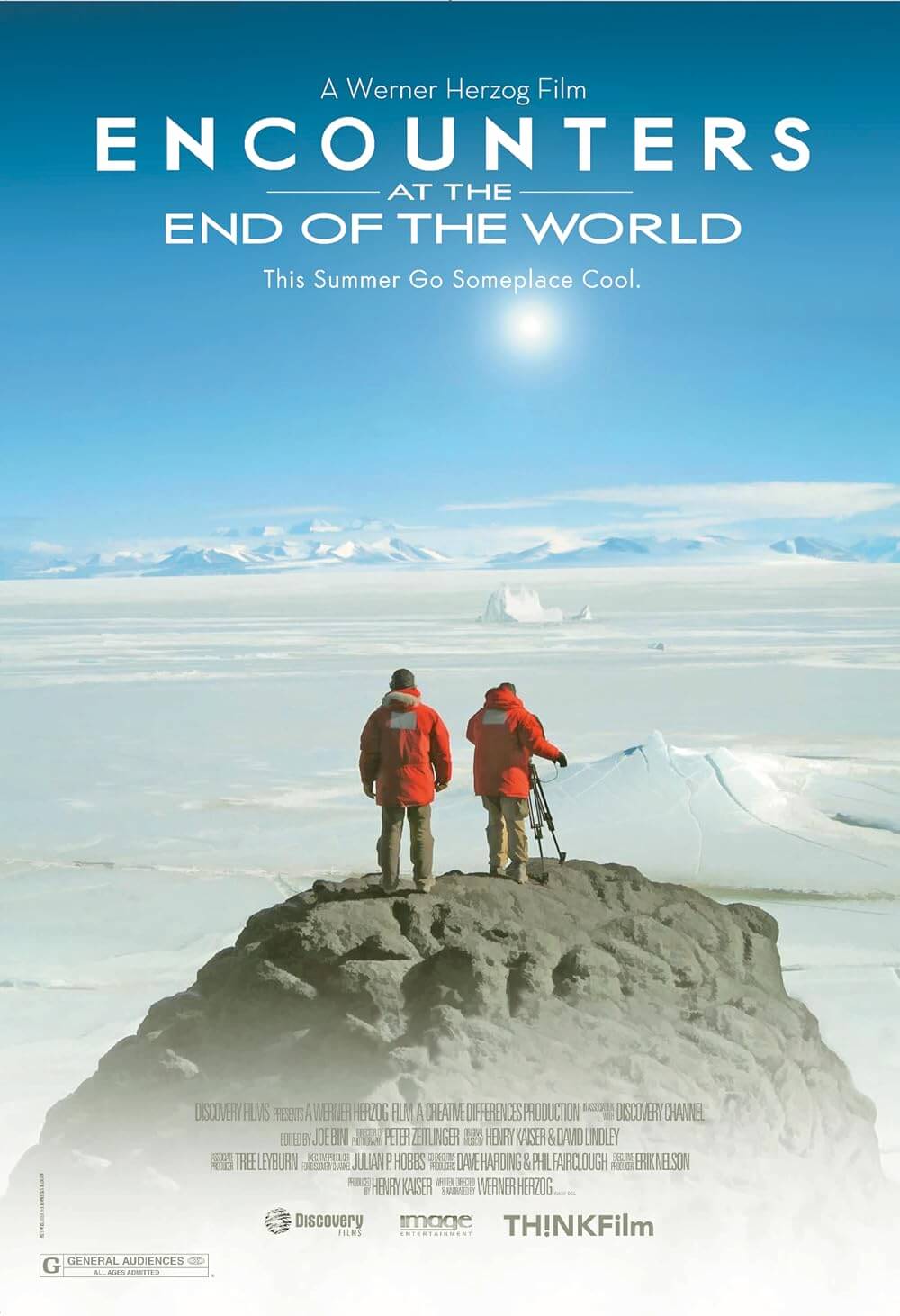

Herzog’s personal views on Nature express his stylization of truth. For instance, in his 2007 documentary Encounters at the End of the World, Herzog is quick to distinguish his film from March of the Penguins, the popular 2005 doc by Luc Jacquet about Antarctic emperor penguins, which took a cutesy and anthropomorphized view of Nature. Herzog believes people “prefer to tell children fairy tales about the kindness of animals, but in truth the natural world operates in accord with harsh principles.” Herzog derides the “cute and fluffy” documentaries about Nature or animal life, going so far as to claim there is more truth in hardcore pornography. As Herzog tries to understand why people behave the way they do and why they subject themselves to Nature’s vast, unknowable sublimity, he finds poetic truth in the reasons Treadwell inserted himself into Nature and understood it—even when Treadwell’s views clash with his own. In one sequence, Treadwell is enraged into a rant when he finds a cannibalized bear cub eaten by a hungry parent. Herzog notes, “Here I differ with Treadwell. He seemed to ignore the fact that in Nature there are predators… I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony, but chaos, hostility, and murder.” Nevertheless, Herzog admires Treadwell in a way. Treadwell is a familiar Herzogian character, a “Holy Fool” who, as described by critic Amos Vogel, “dares more than any human should, and who is therefore—and this is why Herzog is fascinated by him—closer to possible sources of deeper truth though not necessarily capable of reaching them.”

Herzog’s personal views on Nature express his stylization of truth. For instance, in his 2007 documentary Encounters at the End of the World, Herzog is quick to distinguish his film from March of the Penguins, the popular 2005 doc by Luc Jacquet about Antarctic emperor penguins, which took a cutesy and anthropomorphized view of Nature. Herzog believes people “prefer to tell children fairy tales about the kindness of animals, but in truth the natural world operates in accord with harsh principles.” Herzog derides the “cute and fluffy” documentaries about Nature or animal life, going so far as to claim there is more truth in hardcore pornography. As Herzog tries to understand why people behave the way they do and why they subject themselves to Nature’s vast, unknowable sublimity, he finds poetic truth in the reasons Treadwell inserted himself into Nature and understood it—even when Treadwell’s views clash with his own. In one sequence, Treadwell is enraged into a rant when he finds a cannibalized bear cub eaten by a hungry parent. Herzog notes, “Here I differ with Treadwell. He seemed to ignore the fact that in Nature there are predators… I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony, but chaos, hostility, and murder.” Nevertheless, Herzog admires Treadwell in a way. Treadwell is a familiar Herzogian character, a “Holy Fool” who, as described by critic Amos Vogel, “dares more than any human should, and who is therefore—and this is why Herzog is fascinated by him—closer to possible sources of deeper truth though not necessarily capable of reaching them.”

Grizzly Man observes that when people fail to find their place in civilization, they risk themselves and even madness by going into Nature in search for truth. This is a Holy Fool’s errand. Through their search for meaning in Nature, they ironically find a cruel, albeit beautiful reality that creates the impression of oneness within its indifference, which could either fulfill a person’s desire for solitude or propel their madness. There’s a scene in Encounters at the End of the World in which a solitary Antarctic penguin leaves its colony and heads into certain doom, walking not in the direction of the sea but inland toward barren mountains. In trying to understand the penguin’s behavior, Herzog asks the resident penguin expert whether penguins experience insanity. “Is there such thing as insanity among penguins? … Could they just go crazy because they’ve had enough of their colony?” In this moment, Herzog seems to make an indirect connection to someone like Treadwell, who abandons civilization and heads, like the penguin, somewhere he does not belong. Yet Herzog tries to understand Treadwell, and the lone penguin, with a sense of wonder and awe, but also a reflective awareness of his subject’s reckless choice: “As if there was a desire in him to leave the confinements of his humanness and bond with the bears, Treadwell reached out, seeking a primordial encounter. But in doing so, he crossed an invisible borderline.”

In contrast to his more creative flourishes, Herzog’s approach to interviews seems more observational. He seeks truth in the eyes of his interview subjects, who often look directly into the camera, where he finds truth in the way people perform for the camera and what occurs after they stop performing. His interviews relay truth by lingering a moment or two after an interview subject is done speaking, searching for the subject’s pretense to drop and expose a kernel of truth. After Herzog interviews Treadwell’s parents about their late son as they vulnerably grip his Teddy Bear, the camera explores the truth of the interview’s pretense and evident loss in their expressions in the moment after their statement is over. Herzog’s interviews also showcase subjects who act out for the camera, and the director seems to encourage it. Pathologist Franc Fallico in Grizzly Man seems to be performing in the morbidly enthusiastic role of the coroner, and cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger seems to delight in Fallico’s performance, connecting with him and following the elaborate act to fully understand the subject in that moment. Similarly, Herzog does not remark on Treadwell’s friend, Warren Queeney, an actor who treats the camera like a stage audience, looking off into the distance and reciting his memories of Treadwell like the performance of a one-man show.

Typically, documentaries are driven by the desire and pleasure of knowing; they seek to discover, uncover, and inform. But Herzog sometimes withholds to create a sense of lasting curiosity or, in the case of Grizzly Man, support his notion of the sublime and unknowable horrors of Nature. In perhaps the film’s most famous scene, Palovak allows Herzog to listen to Treadwell’s final recording that captures the audio of Treadwell and Huguenard as they are attacked and killed by a desperate grizzly. Herzog hunches, listening intently to the audio on headphones as Palovak, who has never listened to the tape, watches. The viewer does not hear the audio, only Herzog, who begins to describes what he’s hearing. But then he pauses and removes the headphones. “You must never listen to this,” he tells her, and then suggests that she destroy the recording. The result of the scene implies the unknowable horror that Treadwell and Huguenard experienced, while also showing Herzog haunted by Nature’s cruelty. The scene reveals Herzog’s humanist intentions; though eccentric and confrontational in the face of traditional documentaries, he is not a grotesque provocateur. Herzog explained his decision, “Number one, it was clear to me we are not doing a snuff movie. Number two, it occurred to me instantly, you have to respect the privacy and the dignity of an individual death.”

Typically, documentaries are driven by the desire and pleasure of knowing; they seek to discover, uncover, and inform. But Herzog sometimes withholds to create a sense of lasting curiosity or, in the case of Grizzly Man, support his notion of the sublime and unknowable horrors of Nature. In perhaps the film’s most famous scene, Palovak allows Herzog to listen to Treadwell’s final recording that captures the audio of Treadwell and Huguenard as they are attacked and killed by a desperate grizzly. Herzog hunches, listening intently to the audio on headphones as Palovak, who has never listened to the tape, watches. The viewer does not hear the audio, only Herzog, who begins to describes what he’s hearing. But then he pauses and removes the headphones. “You must never listen to this,” he tells her, and then suggests that she destroy the recording. The result of the scene implies the unknowable horror that Treadwell and Huguenard experienced, while also showing Herzog haunted by Nature’s cruelty. The scene reveals Herzog’s humanist intentions; though eccentric and confrontational in the face of traditional documentaries, he is not a grotesque provocateur. Herzog explained his decision, “Number one, it was clear to me we are not doing a snuff movie. Number two, it occurred to me instantly, you have to respect the privacy and the dignity of an individual death.”

Given his deep respect for human dignity and Nature’s sublimity, Grizzly Man shows Herzog’s bewildered fascination with the Holy Fool’s willingness to face it. For Herzog, only the human race would be so mad to think it could conquer the chaos of Nature. His film suggests that Nature does not have humanity’s sense of romanticism, justice, fairness, or empathy. There is not a common language or mutually realized understanding between humans and animals. It is like trying to communicate with chaos, to use Herzog’s term. Treadwell seems like a person in a foreign country who does not speak the language and has no ability understand the local culture beyond his own projections. Treadwell values the lives of wild animals, even as he gives them cutesy names and claims ownership of them. Because of his own personal issues that can only be speculated upon, he values animals so much that he projects human qualities onto them and ignores the harsh reality of Nature—though he frequently acknowledges the dangers around him. He makes it his personal mission to protect his animal “friends” from perceived invaders on the land, but at the same time, he breaks important rules of the national park by closely interacting with several bears and foxes, instead of respecting their space. He deludes himself into thinking he’s part-bear and that he has somehow gained the trust of these animals.

Treadwell’s personal issues warped and also informed his understanding of Nature, while his psychological state deteriorates throughout the course of his footage, suggesting that solitude made him deluded and paranoid. For example, the sequence where he examines “creepy” evidence of a threat (a smiley face drawn on a rock) shows that Treadwell has built-up the idea of a conflict in his head: “It’s obviously here to upset me… Now it doesn’t say, ‘Hi, Timothy. We’re gonna fucking kill you.’ It doesn’t say, ‘Hi, Timothy. You’re fucking dead. We’re gonna chop your legs off.’ …But it is some sort of a warning.” Elsewhere, Herzog shows Treadwell’s unstable and worsening state. Remarks like, “How dare they challenge me! How dare they smear me with their campaigns” or a particularly long rant laden with a conspicuous overuse of the F-word show Treadwell feeding on his anger and paranoia about human civilization. At the same time, his increasingly dangerous interactions with the bears seem to be connected to his personal desperation, ultimately leading to his death, all because he does not want to leave his camp at the end of the season. Herzog’s characterization of Treadwell with the footage creates a portrait of a Holy Fool no longer capable of respecting Nature with an appropriate, safe distance.

Treadwell’s one-sided relationship with the bears has both positive and negative outcomes. The relationship served his love for animals and his personal escape from the world of people. He imposes on animals for, at first, selfless reasons, which eventually become selfish, as he sees himself as the bears’ protector. His actions brought attention to the bear situation and the need for conservation, and he brought awareness to schools, his popularity inspiring followers to make donations that helped protect the bears. On the other hand, Treadwell’s mission is not supported by anyone but himself. He never graduated from a university with an education in animal biology or behavior studies; he was simply a guy who loved bears, learned about them independently, and then rushed headlong into the wilderness. He was not doing this “for science” but for himself. Along the way, he violated established park rules and insinuated himself in the bear ecosystem, which is harmful from the perspective of wildlife refuge and protection. Sven Haakanson of the Alutiiq Museum said it best: “He tried to be a bear. He tried to act like a bear, and for us on the island, you don’t do that. You don’t invade on their territory.” Such remarks imply that Treadwell’s presence did more harm to the animals than good, especially in terms of feeding his self-destructive behavior and instability. Though he felt a connection to animals, he was also delusional and seemed to fabricate that connection in his mind, which overwrote any understanding of the innate cruelty of Nature that Herzog describes.

Treadwell’s one-sided relationship with the bears has both positive and negative outcomes. The relationship served his love for animals and his personal escape from the world of people. He imposes on animals for, at first, selfless reasons, which eventually become selfish, as he sees himself as the bears’ protector. His actions brought attention to the bear situation and the need for conservation, and he brought awareness to schools, his popularity inspiring followers to make donations that helped protect the bears. On the other hand, Treadwell’s mission is not supported by anyone but himself. He never graduated from a university with an education in animal biology or behavior studies; he was simply a guy who loved bears, learned about them independently, and then rushed headlong into the wilderness. He was not doing this “for science” but for himself. Along the way, he violated established park rules and insinuated himself in the bear ecosystem, which is harmful from the perspective of wildlife refuge and protection. Sven Haakanson of the Alutiiq Museum said it best: “He tried to be a bear. He tried to act like a bear, and for us on the island, you don’t do that. You don’t invade on their territory.” Such remarks imply that Treadwell’s presence did more harm to the animals than good, especially in terms of feeding his self-destructive behavior and instability. Though he felt a connection to animals, he was also delusional and seemed to fabricate that connection in his mind, which overwrote any understanding of the innate cruelty of Nature that Herzog describes.

Nevertheless, Herzog, ever the filmmaker, remarks at one point: “Treadwell is gone. The argument about how wrong or how right he was disappears into a distance, into a fog. What remains is his footage.” He is capable of distancing himself from his subject for a moment and appreciating what Treadwell captured as a filmmaker. From his views on the “ecstatic truth” that emerges from humans interacting with Nature, it becomes evident that Herzog is a personality unto his films, shaping his choice of subject matter and his formal approach. Given his personal influence, Herzog is considered by film theorists to be resistant to analysis, as understanding one of his films becomes as intricate as trying to understand the complexities of a human being. One thing remains: his drive to create and advance the art of cinema. “As a filmmaker, sometimes things fall into your lap which you couldn’t expect, never even dream of, there is something like an inexplicable magic of cinema” Herzog notes, citing several “empty moments” or animal interactions found in Treadwell’s footage that convey such uncanny magic. Treadwell’s near master-pet relationship with a den of foxes is particularly endearing. In these magical moments, however empty or terrible, Herzog finds his version of truth: “And while we watch the animals in their joys of being, in their grace and ferociousness, a thought becomes more and more clear: that it is not so much a look at wild Nature as it is an insight into ourselves, into our nature. And that to me gives meaning to his life and to his death.”

Audiences willing to confront Grizzly Man on the terms of its director discover an infectious curiosity and sense of understanding beyond words. Though the film explores Nature and natural phenomenon as typical documentaries often do, Herzog’s films are not factual documents. His singular perspective inspires new ways of looking at the sublimity of Nature and how people choose to interact with it. The way he questions people and their place in the world forces his audience to examine their own lives and understand their surroundings, as well as consider how far they would go to achieve their pursuits. Through Herzog’s approach, his audience realizes that there is more to any situation than the cold facts represented by cinema vérité. Unfortunately, the truth he finds in his films cannot always be succinctly articulated, and his dismissal of facts rarely provides the intellect with a solid foundation on which to process his films. It is a dialectic between humans and Nature that must, in some cases, be felt to be understood. Even so, the involving dialectic in Herzog’s films makes the experience of the documentary more personal and potentially more affecting for the viewer on an emotional level.

Grizzly Man is not an objective documentary, and Herzog is not an objective filmmaker. He does not separate himself from his documentaries or limit his creative influence on his films. Understanding any one of his documentaries involves understanding his perspective. By attempting to understand Herzog, his audience experiences the same search for truth over fact that Herzog yearns to find in his subjects’ interactions with Nature. Though documentaries often carry an expectation derived from cinéma vérité that they present things as they really are—which itself is an illusion—for Herzog, objectivity limits the potential poetry fundamental to cinema. If cinema is a creative medium first, then Herzog’s awareness of and openness in his subjectivity remain essential to his documentaries. His interview style, camerawork, use of music, and other creative choices all come from his pursuit of truth as he sees it. Herzog takes a rare approach to the documentary: a poetic documentary, which relies on the filmmaker’s expressive voice, both literal and figurative, through narration and formal touches, to shape his film. By watching Grizzly Man, viewers undertake a poetic experience that explores not only the poetic truth that results from the film’s subjects confronting Nature’s sublimity, but also the perspective of their poet-filmmaker.

Grizzly Man is not an objective documentary, and Herzog is not an objective filmmaker. He does not separate himself from his documentaries or limit his creative influence on his films. Understanding any one of his documentaries involves understanding his perspective. By attempting to understand Herzog, his audience experiences the same search for truth over fact that Herzog yearns to find in his subjects’ interactions with Nature. Though documentaries often carry an expectation derived from cinéma vérité that they present things as they really are—which itself is an illusion—for Herzog, objectivity limits the potential poetry fundamental to cinema. If cinema is a creative medium first, then Herzog’s awareness of and openness in his subjectivity remain essential to his documentaries. His interview style, camerawork, use of music, and other creative choices all come from his pursuit of truth as he sees it. Herzog takes a rare approach to the documentary: a poetic documentary, which relies on the filmmaker’s expressive voice, both literal and figurative, through narration and formal touches, to shape his film. By watching Grizzly Man, viewers undertake a poetic experience that explores not only the poetic truth that results from the film’s subjects confronting Nature’s sublimity, but also the perspective of their poet-filmmaker.

Bibliography:

Aimes, Eric. “The Case of Herzog Re-Opened.” A Companion to Werner Herzog. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2012, pp. 393-414.

Burke, Edmund. “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful.” Aesthetics: A Comprehensive Anthology, Ed. Steven M. Cahn and Aaron Meskin. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2008, 113-122.

Cagle, Chris. “Postclassical Nonfiction: Narration in the Contemporary Documentary.” Cinema Journal. Vol. 52 Issue 1. 2012, pp.45-65.

Cronin, Paul. Herzog on Herzog. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2002.

Herzog, Werner. Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of ‘Fitzcarraldo’. Ecco, Reprint Edition, 2010.

LaRocca, David. “‘Profoundly Unreconciled to Nature’: Ecstatic Truth and the Humanistic Sublime in Werner Herzog’s War Films.” The Philosophy of War Films, David (ed. and introd.) LaRocca, UP of Kentucky, 2014, pp. 437-482.

Plantinga, Carl. “What a Documentary Is, After All.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 4/1/2005, Vol. 63, Issue 2, p. 105-117.

Prager, Brad. The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth. London: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review