The Definitives

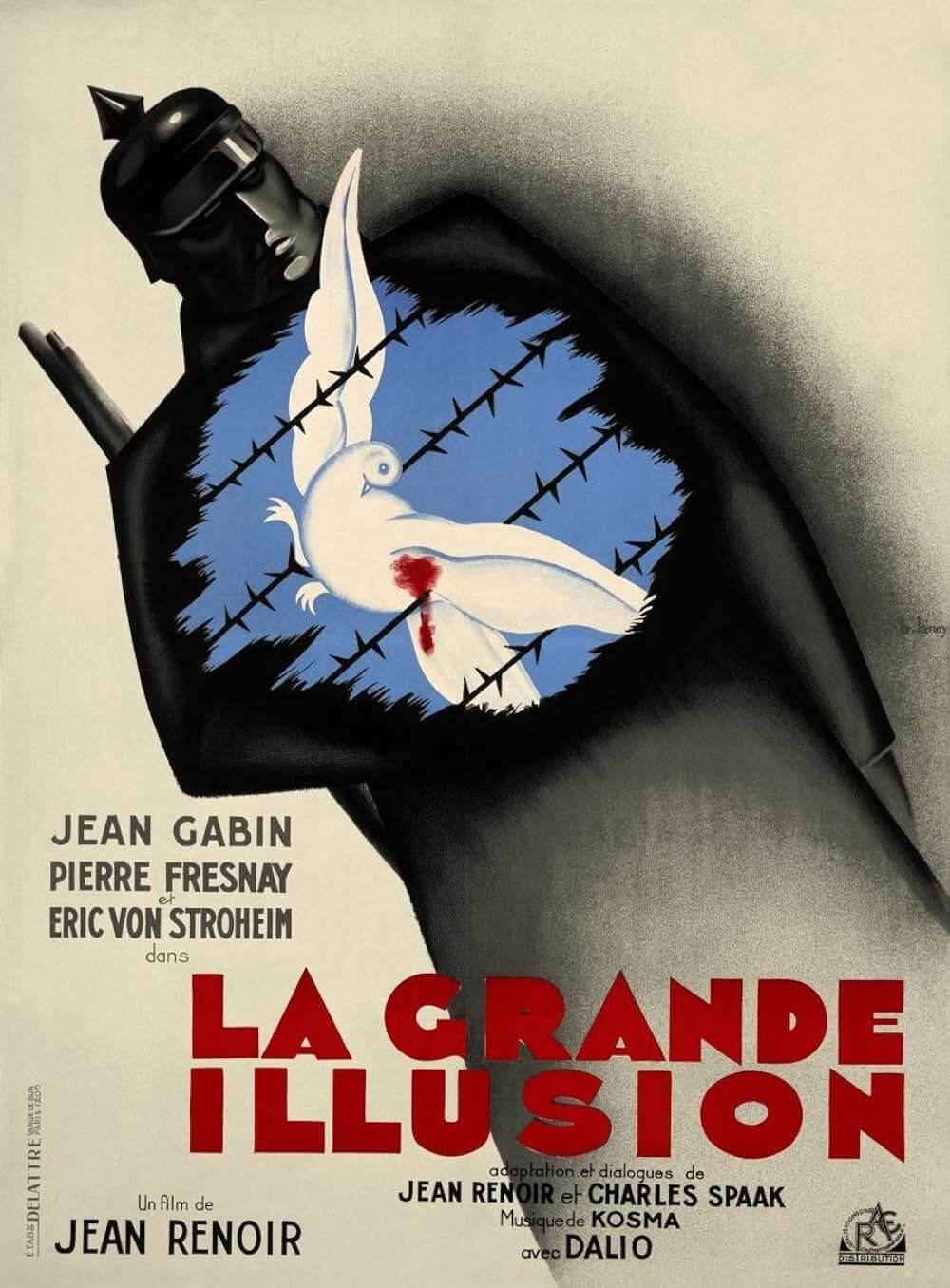

Grand Illusion (1937)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Pregnant with social, humanist, and auteurist truths, Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion contains equal measures of compassion and realism. Beneath a World War I story about POW encampments, the great French filmmaker yearns for a world without borders, where people of dissimilar ethnic or political backgrounds might still form bonds through whatever commonalities they share. The 1937 masterpiece greets traditionalist notions of custom and decorum with admiration for their time-honored merits, but also with reproach for their ability to segregate people. The miracle of Renoir’s film is that, even while supplying an almost didactic discussion, the director never reduces his characters to mere symbols with which he builds up the film’s meaning. Grand Illusion may be populated by a cadre of individual characters and narrative breadth steeped in symbolism, but Renoir restrains the film’s potential for theatrics and poetic staginess, offering instead an uncommon realism that defines his personal style. Fashioned with impeccable verisimilitude, Renoir graces his pacifist film with a splendid thesis that recognizes the unfortunate constructs that facilitate an easier life—an unfailing consciousness of human-made boundaries that separate humanity through nationalism and xenophobia—while also recognizing they perpetuate conflict when blindly followed. The message of Renoir’s picture is universal in its humanism that transcends all else.

Grand Illusion ponders, among other concerns, the downfall of the European aristocratic order before the war. Through his discussion, Renoir examines the nature of friendships, languages, and the understanding and acceptance of diverse cultures, the war notwithstanding. His film’s heart is a group of men, as opposed to political stations, who ironically find their common ground in a series of German POW camps. With his refined onscreen persona, Pierre Fresnay flawlessly exemplifies the monocled French blueblood Captain de Boëldieu. Parisian everyman Jean Gabin is Maréchal, the rugged working-class pilot. And Marcel Dalio plays the Jewish banker, Rosenthal, who shares his care parcels with friends for welcome meals of chicken, foie gras, mackerel, and cognac. When they first meet in the rugged Hallbach camp, these men, and many others with them, attempt to escape, albeit unsuccessfully, and as a result are moved to the castle Wintershorn. Here, they are prisoners under Captain von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim), a rigid classicist and traditionalist who takes a shine to the likewise erudite de Boëldieu. In another bid to escape, de Boëldieu betrays the German captain with whom he’s formed a bond, while Maréchal and Rosenthal escape. De Boëldieu dies by von Rauffenstein’s regretful bullet. Maréchal and Rosenthal take refuge in the mountains, stopping at a German farm where Maréchal falls in love with its sole inhabitant, Elsa (Dita Parlo). Nevertheless, Maréchal and Rosenthal must push on to safety over the Swiss border.

Grand Illusion’s most basic contributions to cinema include a series of well-established tropes later used in prison-escape films. Hiding their escape hole under floorboards beneath a bunk, the men tie a rope to a single mole digging the passage deeper. Air flows to him through a tube of cans, and a string attaches to a warning tin that he pulls to sound his readiness for relief. The excess earth is stored in small bags and emptied from under their pants during their faux gardening activities. Later escape-centric films such as Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption (1994), John Sturges’ The Great Escape (1963), and Le Trou (1960) by Jacques Becker (himself the assistant director on Grand Illusion) replicate aspects of the escape procedure established in Renoir’s film. But this is not a film about escapes; it dwells on the conflicts among men. The prison camps show the entire national community in a bubble. Ideas such as nationalism, class, and race create the conflict between the prisoners; however, at the same time, they bring people together. In a German mess hall after de Boëldieu and Maréchal are shot down in their plane in the first scenes, Maréchal is seated next to a German who speaks French. In another film, these two would have nothing but conflict and hatred for one another. Instead, the scene progresses as the German speaks French and, like Maréchal, worked at a car factory in Lyon before the war. A moment later, Maréchal is delighted to know the German, who even offers to cut Maréchal’s meat since his arm is injured. In a deeper sense, Grand Illusion is about the connections among people, while also depicting how people are similar as a process of discovery that requires us to sift through their differences.

Renoir’s pursuit of commonality among people harkens back to his nostalgia for the belle époque, a zenith in France when art, science, and culture flourished following the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. The era lasted until World War I broke out in 1914, and, compared with the grueling years that followed, it was a golden age. During this period, Renoir grew up under his father, impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who flourished throughout the belle époque and, much like his contemporaries, shunned concepts of progress and financial gain for more humanist pursuits such as art and culture—only they could achieve a “common understanding between men.” When Jean published Renoir My Father in 1962, he remembered his father declaring the end of his world in 1915. All common understanding between members of the human race was obliterated in the face of a worldwide war. The son was very much like the father in this regard. When Renoir enlisted in the cavalry in 1913, he did so because his father was a cavalryman during the Franco-Prussian War, and what a romantic, adventurous war that seemed to be. By contrast, World War I was ugly and complicated; in a brash decision fueled by youthful ideals about wartime adventure, he joined the infantry to see some action. He was quickly injured and nearly lost his leg to gangrene, which left him with a lifelong limp. In a similarly romanticized view of fighter pilots, he joined the air force and served as an aerial photographer with a reconnaissance squadron. Using a camera for the first time, he took photos of German lines from a slow, wooden twin-engine airplane. As Renoir carried out an assignment one day, German aircraft attacked his plane. Swooping to his rescue was a French pilot, Major Armand Pinsard, who shot down the attackers and saved Renoir’s life.

Many years later when Renoir became a filmmaker and was in the midst of production on Toni (1935), he had a chance meeting with Pinsard. During the shoot, filming was interrupted by aircraft overhead. When Renoir contacted the nearby base to complain, he rediscovered Pinsard, now a General. The two began meeting regularly and sharing recollections of the war. Renoir was particularly stirred by Pinsard’s stories about his imprisonment in German POW camps and subsequent escapes. These retellings, along with those of Renoir’s friend and co-writer Charles Spaak, who served on the French Front in 1915 and was also captured and imprisoned by the Germans, supplied the inspiration for Grand Illusion. Though, only in a skeletal form. Before all that, something far greater influenced Renoir and his filmmaking style, shaping Grand Illusion and the director’s other films. While serving as a ceramicist, as his father had done before, Renoir had taken up painting and had become a habitual moviegoer, beginning with the first films of Charles Chaplin imported to France in 1916. Not until 1922, when Renoir saw Erich von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives about ten times, did the future director understand how the realism of natural gestures and images could represent the “national tradition” of France in subtle ways. To accomplish this himself, Renoir first set out to make films as a platform for his wife, Andrée, yet borrowed from von Stroheim’s use of long takes with no edits, all within a single shot, to render the importance of watching and identifying the qualities that would ultimately define what it meant to be French. Renoir made nine silent films in the five years between 1924 and 1929, five of them with Andrée.

Not until 1931 did Renoir make a sound film. On purge bébé (Baby’s Laxative) not only featured sound but also offered the first toilet-flushing sound in any sound film. This, and many of his subsequent films until Grand Illusion in 1937, served as harsh critiques of bourgeois culture. Though Renoir’s signature humanist style would not fully emerge in his early works, what remained obvious was the director’s interest in higher-class characters being usurped or driven mad by lower-class characters. La chienne (1931) follows a bourgeois man who becomes fixated with a prostitute and eventually kills her when she betrays him; in Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932), Michel Simon plays a derelict homeless man who causes a ruckus in the home of the bourgeois man who saved him from drowning; and Le crime de Monsieur Lange (1935) is about workers who form a cooperative in lieu of their office going bankrupt. By 1936, with Renoir’s adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s famous play The Lower Depths, about a group of unemployed workers in grim social conditions, the director was established as the foremost socialist filmmaker in France and attracted the attention of the Communist Party. And after Grand Illusion, his ongoing string of naturalist films solidified his status as the premier auteur among French critics writing for Cahiers du cinéma in the 1950s, who described directors as the primary voice responsible for their work, just as an author is for a book.

When writing Grand Illusion, Spaak, who wrote The Lower Depths, drew on several of Pinsard’s stories, Renoir’s recollections, and a few of his own, incorporating them into his screenplay. For two years, Renoir and Spaak tried to secure a producer, but not until charismatic actor Jean Gabin, who would later become French cinema’s greatest star, voiced interest did the production company RAC (Réalisations d’Art Cinématographique) agree to back the film. By the time shooting began at the start of 1937, Spaak and Renoir were on their third draft of the screenplay; however, not all of what was written in the third draft made it to the screen. Renoir’s process was one of evolution, and rarely did his initial vision become the picture that was written or that ended up onscreen. His films did not document; he invented through them. For example, earlier drafts of the screenplay were far bleaker. One removed sequence involved a prisoner who was placed in solitary confinement for 60 days until he was nothing more than skin and bones. Several other scenes were removed due to budget constraints. And yet, the finished film plays as if tightly constructed from the start, because Renoir would reshape the picture according to any changes, making it flow seamlessly until each component feels necessary and vital within the context of the story and its themes. By amalgamating their wartime experiences into the screenplay, Renoir ensures the film has an ethereal, almost innocent quality, especially after World War II. Decades later, Renoir wrote that he felt the film was “like a ghost” and “about a marvelous civilization which, alas, belongs only in the past.”

Notice how the prisoners in Grand Illusion—Frenchmen, Russians, Englishmen, Americans—share an unspoken understanding among them, where fraternity seems graver than any class division. In spite of rank, nationality, or race, everyone works in the tunnel to escape, putting in time to dig the hole, breathing through a makeshift air tube, and scraping out soil, each inch bringing them closer to freedom. The authenticity of the relationships created by Renoir resonates in the tangible status of everyone, from the main players to comic relief such as Traquet, the blithe actor played by Julien Carette. Even German security guards such as Arthur (Werner Florian), the butt of Traquet’s joke during his staged talent show, feel dimensional. Without begging for brotherhood or an all-out sense of internationalism—or suggesting that everyone should put down their guns and hug—Renoir dissolves the frontiers between people. He offers an old German woman who regards the French prisoners and reflects on the “Poor boys.” He shows us French prisoners looking out the window at the showmanship of the German assembly and confessing, “You have to admit, it’s stirring.” Though his narrative may not dwell on realism with a documentarian’s devotion to reality, Renoir observes decisive details that make the film’s meaning more significant through the abstraction of dramatic wisdom. His entire narrative schema seems to inhabit moments that point to real, authentic, or natural relationships, doing so in a way that makes us forget the film is progressing as a constructed motion picture. Indeed, Renoir’s film centers on distinguishing between reality and dramatic theatricality, and he deliberately blurs the lines between the two.

Consider the scene where the prisoners prepare a diversionary talent show. Having received trunks of costumes thanks to Rosenthal, the men laugh and joke as they look through their inventory, dreamily and yearningly discussing how women’s fashions have changed. And then, in what is perhaps the film’s most famous scene, one of the men appears in a dress and wig, having tried it on as a lark. His thin frame is just enough to freeze the men, locking them in a reminiscence of femininity. The French soldier looks down at himself awkwardly. “Sure looks funny,” he says, quite bashful. The men, caught within their memories and longings, their homesickness, their thoughts of their wives and sweethearts, can do nothing but gaze at the bashful soldier, embarrassedly looking himself over. Renoir suggests there is no escape from reality through the unreality of theater. However expressive theatricality or drama may seem, the viewer’s process of watching requires consumption and digestion; the viewer absorbs what appears on stage, and then applies and relates to it through their own associations and experiences. Renoir’s undercurrent theme is that even escapist cinema or theater contains relatable content and never fully allows us to escape. Accordingly, he makes his film as authentic as possible; even while hoping for an unquestionable, unrealistic ideal, his film emanates surprising realism.

Renoir’s camera shapes the film’s sense of reality, or more accurately, its sense of truth. Shooting plainly but narratively dense, Renoir employs fluid, not showy, camera movements to avoid cutting a scene into choppy sections. The director creates a dramatically complete sequence by engaging the viewer on a visual level; he uses a wide depth of field and shifts the camera’s position to reframe the image, avoiding fragmentary cuts that would detach the audience from the unfolding story. And when his editor—credited as Huguet, also known as Madame Marthe Huguet, Renoir’s editor on La règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game, 1939)—makes a cut, the transition never jolts the viewer. Her cuts are invisible. This desirable approach can be found in several Renoir pictures and articulates his desire to singularly characterize the relationships and connections between men on either side of the conflict with unquestionable clarity and precision. Renoir’s scenes convey a flow and natural movement rather than adherence to a schematized plot. And perhaps Renoir’s sense of truth and authenticity informs his films’ realist preoccupations, helping them unfold with a dramatic poetry that feels genuine yet allows the director to wink through the camera, capturing his sly critiques in their natural environment—as opposed to an overtly expressive display.

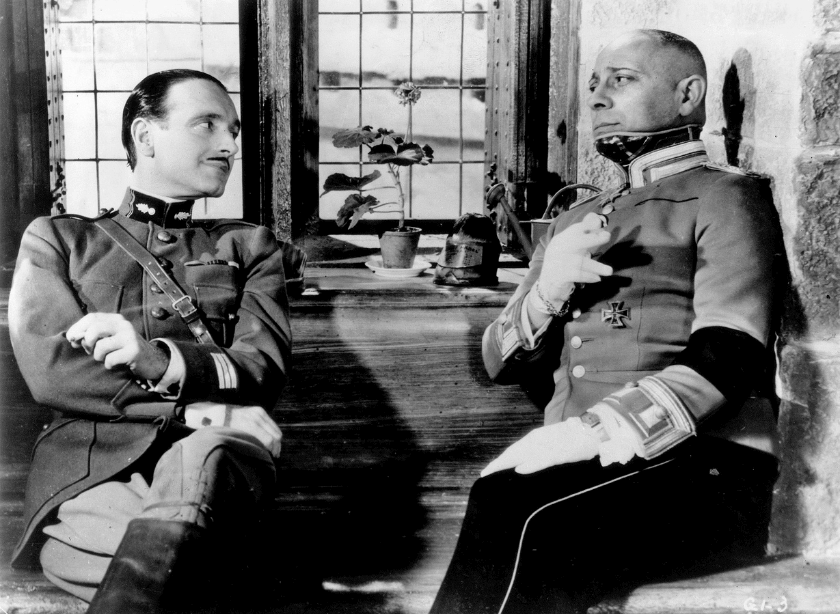

Take the role of Captain von Rauffenstein, the German administrator who first captures de Boëldieu and Maréchal and oversees their final POW camp, a reinforced thirteenth-century castle. Throughout the picture, the character demonstrates his favoritism for officers, beginning when he shoots down de Boëldieu and Maréchal in the first scenes. “If they’re officers, invite them for lunch,” he tells a soldier. When the Frenchmen arrive to dine with their German hosts, von Rauffenstein even apologizes for bringing down their plane, as though such a wartime act was poor etiquette before a meal. Von Rauffenstein’s outlook rests on the elitist view that officers are the privileged, the upper class of military hierarchy. It’s a charming, if quite mad, perspective during wartime, but also a troubling German perspective of superiority that anticipates fascism. To be sure, as Renoir filmed Grand Illusion in 1937, Adolf Hitler had already come to power, and Nazi Germany had broken the 1919 Treaty of Versailles by reoccupying the Rhineland, violating the terms established at the end of World War I. Renoir felt there was no place for an elitist officer class in the modern world; he felt his contemporary army was “plebeian,” a generation of admirable working-class figures like Maréchal. Von Rauffenstein and de Boëldieu epitomize Renoir’s representations of the officer class in general, on both the German and French sides. They come from esteemed backgrounds, moneyed families, nobility that exists within social distinctions that disappeared after World War I. Indeed, von Stroheim’s character points out that the war “will mean the end of the Rauffensteins and the Boëldieus.” This is evident in Renoir’s officers, whom he presents as embodiments of stiff, strict, and inhuman corporeal regimentation. At the same time, they represents a very romantic French decency, which the director describes as an “easygoing spirit,” marked by refined grace and noble pride.

Von Rauffenstein was originally an inconsequential role, but the character was expanded when Renoir cast his own idol, filmmaker Erich von Stroheim. An incredible influence over Renoir’s work, the famously egomaniacal director of Greed (1924) and The Wedding March (1928) had since been shunned in Hollywood. And so, when the nervous and doting fan Renoir asked his artistic inspiration, von Stroheim, now a desperate erstwhile figure, to take a role in his new picture, the minor part suddenly grew into something much more telling. Renoir worked closely with von Stroheim to deepen the von Rauffenstein character, expanding its potential to include aristocratic airs, while adding much of the film’s class commentary into the already prevalent social and political allusions. Renoir and his assistant director, Becker, rewrote the existing screenplay to accommodate von Stroheim’s presence, while von Stroheim contributed to his character’s costume—he designed the neck brace, selected a monocle, and insisted on wearing white gloves. Other flourishes surrounding von Rauffenstein were just as improvisational. One day, while exploring the castle that served as von Rauffenstein’s camp, set designer Eugène Lourié found a geranium in a pot. Renoir decided to use it and incorporated the heartbreaking moment when von Rauffenstein cuts the flower after de Boëldieu is killed trying to escape.

Without the chance inclusion of Renoir’s hero von Stroheim playing von Rauffenstein, which further developed the character and his symbolic subtext on the classes, Grand Illusion might never have developed its message to such universal appeal. Besides the political borders and the POW camp fences, classes represent yet another boundary in Grand Illusion and succeed as a metaphor for all others, just as the reverse is true of political borders signifying petty class conflicts. Von Rauffenstein’s presence and his class-driven civility during wartime delineate the insanity of war and the demise of his class, from his conversations in English with de Boëldieu, which cannot be shared by the lower-class prisoners and guards unable to speak English, to his insistence that men like them have nothing in common with grunts like Maréchal and Rosenthal. De Boëldieu is more accepting of his class’ disintegration, arguing that they cannot impede progress. But just by von Rauffenstein’s appearance, wrought with war wounds such as his neck stiff in a brace or his fire-scarred hands covered by white gloves, Renoir presents a member of a dying breed—his physical state an embodiment of that eventual death. At the same time, Renoir’s rendering of the aristocratic military code has an elegant appeal, despite the inherent paradox, ripening the film’s anti-war position. Ultimately, the aristocrats destroy each other when von Rauffenstein is forced to shoot down de Boëldieu, who sacrifices himself for Maréchal and Rosenthal’s escape, thus robbing von Rauffenstein of his only pseudo-companion in the war.

Renoir’s changes to his original screenplay proved so significant that Gabin, who only agreed to participate because of the first draft’s merits, voiced his displeasure with the finished film. Likewise, Spaak refused to even attend the premiere. Many believed that Renoir’s indulgence of von Stroheim went too far. Years later, Renoir told the Cahiers du cinéma, “When one makes a film, the relationships between the collaborators—I should almost say accomplices—become strangely intimate.” Through Renoir’s penchant for collaboration, he synthesized an original style that drew on influences around him, both in front of and behind the camera. He never yearned for or expected complete control of his actors or story, as filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock or Stanley Kubrick later became known for. Renoir considered a film director to be an orchestrator of chaos. In an interview from 1931, he compared directing to his former occupation as a ceramicist: “The ceramicist imagines a vase, makes it, paints it, bakes it—and after several hours he takes out of the oven something completely unexpected and very different from what he had wanted to make or thought he was making.” Regardless of how he was influenced, Renoir remains Grand Illusion‘s author because, as his actors, writers, and other talent offered their ideas in a relatively collaborative process, he remained true to his concepts. He allowed himself to be influenced, yet his integration of other ideas into his own was an organic process through which he never lost touch with his own art, or the ideas that inspired the film in the first place.

Even so, there are multiple kinds of realism and Renoir’s proves the most natural of them, which further signifies his authorship. Italian Neorealists relied on location shooting, used unprofessional actors, and portrayed subjects drawn from everyday life, such as Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D. (1952). French Poetic Realism was more expressive, with many of its finest examples written by poet Jacques Prévert, whose elegiac dialogue was itself high drama and called attention to its own poetry, such as in Marcel Carné’s masterful Les enfants du paradis (The Children of Paradise, 1945). Renoir achieved his own brand of realism—let us call it Naturalist Realism—through detail. He insisted that Gabin wear his original aviator’s jacket and consulted his German art historian friend, Carl Koch, to confirm the authenticity of the German military uniforms in the film. More than once, Koch and von Stroheim argued over details, as von Stroheim believed it was an artist’s duty to distort reality for his own purposes. But Renoir’s obsession with authentic details shaped his style. In several sequences, he opens a scene not with an establishing master shot but with a close-up of objects in a room that gradually pans back to a wider view. When von Rauffenstein is introduced, the shot begins with a crucifix in the chapel, then moves to a portrait of a military figure, the Geranium, a table set for champagne, a pistol atop Casanova’s memoirs, a photograph of a woman, swords, and so forth. These details outline von Rauffenstein’s character, a romantic, chivalrous, elitist, and exacting personality. Stanley Kubrick would later borrow this approach, most notably in Barry Lyndon (1975).

Beyond superficial details, Renoir worked closely with his actors on their performances. When he led the first reading of the script, he made the actors speak in monotone, without emotion, just reading the lines. The intention was to prevent them from filling their role with something informed by their previous work and “bound to be banality,” as Renoir once wrote. Original performances only come from an actor progressively discovering the role and growing into it. Eventually, they would find themselves in the role and inhabit it less as a performance than as an embodiment, thus purveying Renoir’s Naturalist Realism. For this reason, Renoir shot in deep focus to link the foreground, middle ground, and background; he also employed longer takes to give his actors more time to live and breathe in their roles. For Renoir, there was no more important tool in his arsenal than his performers. From this approach, Gabin gave a superstar-making performance that launched his career; and ironically, he shows a broader emotional range in Grand Illusion than in any subsequent picture. Gabin seems so cavalier and confident early on, but over time, after his capture, the actor slowly breaks down and almost loses himself to despair. The character is revitalized during the escape attempts and becomes disarmingly tender during the final scene opposite Dita Parlo. Similarly, many of the French actors who starred in Renoir’s film would become major players in French cinema after Grand Illusion. Parlo, Dalio, Carette, and Fresnay all became popular after the film. And although von Stroheim acted steadily over the subsequent years, he would not have another part like von Rauffenstein until another devoted fan-filmmaker, Billy Wilder, cast him in Sunset Blvd. (1950).

Regardless of Renoir’s naturalism, there is an undeniable theatricality to Grand Illusion, because as much as the director strived for Naturalist Realism, he was also charmed by the theater and theatricality itself. After all, Renoir and Gabin collaborated again in 1954 on French Cancan, a film that celebrated Paris’ most famous dance at the Moulin Rouge. But in Grand Illusion, Renoir contrasts his natural cinematography and performances by the grandiosity of the narrative. His approach to realism was a matter of personal truth, a concept he learned from von Stroheim in the 1920s. “Reality has no value except when it is transposed,” said Renoir, paraphrasing von Stroheim. “An artist only exists if he creates his own little world.” How appropriate, then, that Renoir included von Stroheim in his picture, and how equally appropriate that he was forced to combat von Stroheim over the tone of particular scenes. Renoir wanted his own personal truth to Grand Illusion, his Naturalist Realism that filtered reality through his lens and onto the screen. Through this process, Grand Illusion becomes a representation of Renoir himself—his political and social stances, his appreciation of theatricality and preference for reality, and his yearning for common human understanding beyond borders. Because Renoir has so accurately represented himself in Grand Illusion, as well as other films, he remains an auteur.

Renoir’s film earned international recognition and awakened a larger international audience to the filmmaker’s name. Grand Illusion was first shown in Paris at Marivaux cinema on June 9, 1937. At the same time, The Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (International Exposition dedicated to Art and Technology in Modern Life)—the equivalent of a World’s Fair—was being held in Paris, running from May 25 to November 25 of that year. Given the themes of Renoir’s film, the setting could not be more appropriate. Pablo Picasso’s mural Guernica, the artist’s unabashed anti-war-themed response to the bombing of Guernica in Spain during the Spanish Civil War, was showcased alongside works of modern art by Joseph-Émile Brunet, Alexander Calder, and Joan Miró. Dwarfing Britain’s exhibition were pavilions constructed by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which faced each other on Paris’ Right Bank. Visitors of the Exposition would have to pass by each pavilion if crossing the Pont d’Iéna bridge. The Nazi Germany side was crowned by a massive eagle statue atop a swastika; the Soviet pavilion had two socialist workers, a man and woman, the former holding a hammer and the latter a sickle, reaching out toward the future. An atmosphere of political undercurrents, grandstanding, and artistic revelation was an ideal setting for the debut of Grand Illusion, a film that critiqued such political showboating. With over 30 million attendees at the Exposition, over 200,000 moviegoers saw Renoir’s film during its run at the Marivaux cinema, and it quickly became the highest-earning film in France that year. It would be Renoir’s most successful production.

Shortly thereafter, Prime Minister Léon Blum’s leftist Popular Front government fell, giving way to Marshal Pétain, Vichy France, and the country’s surrender to Nazi Germany. Despite this grim political environment, the film was a success, particularly in the American foreign market, where Renoir would later find his home, albeit temporarily. Grand Illusion won a special prize at the Venice Film Festival for “best artistic ensemble” and would have won the top prize, except Mussolini refused to allow the film the “Mussolini Cup,” the original name for the festival’s best foreign film award. Regardless of its prize, Mussolini banned the film from exhibition in Italy. In the US, a special screening was set up for Eleanor Roosevelt on October 11, 1937, her birthday. After the screening, President Roosevelt announced, “Everyone who believes in democracy should see this film.” Subsequently, the picture ran for twenty-six weeks in New York after its American premiere on September 12th, 1938. And Goebbels, of course, not only banned Grand Illusion but declared it to be the “cinematographic enemy number one” as a result of its pacifism and portrayal of a sympathetic Jewish man, Rosenthal. As Nazi troops marched across Europe, they were ordered to seize copies of the negative. The film was believed to be lost altogether. Fortunately, the Nazis’ obsession with storing banned art was almost as powerful as their capacity to destroy. American soldiers uncovered a negative in Munich in 1945, ironically preserved to near perfection, stored away in an act of control. Similar German warehouses throughout Europe contained other prohibited films, rare books, and priceless works of censored art. A restored treatment of the film was released in 1946, though incomplete, and then considered too kind to the Germans, given the very recent liberation of France. Some reassessments even went so far as to call Grand Illusion anti-Semitic for its lack of outright condemnation of the enemy.

Throughout World War II, Hollywood used Nazis as one-dimensional villains in countless films. By that time, it felt almost sacrilegious for Renoir to render Germans with more than a single dimension. But Renoir’s film was made before the full force of Hitler’s Nazi Party was well known, before people resisted the idea that Germans were human beings. In the early 1930s, pictures about World War I were not merely yarns about fighter pilots, such as Howard Hughes’ epic Hell’s Angels (1930). Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and James Whale’s Journey’s End (1930) delivered vital anti-war themes, despite the actionized degree of their presentation. These pictures depicted the horrors of war in definite terms, honing then-popular anti-war sentiments. As years passed, those attitudes calmed. And when Renoir set out to make Grand Illusion, audiences were more interested in diverting yarns like Howard Hawks’ The Road to Glory (1936) and Edmund Goulding’s The Dawn Patrol (1938). They had forgotten, or wanted to forget, about the horrendous atrocities of World War I. Renoir’s film was much more universal, more far-reaching than a single war. In 1958, Renoir and Spaak edited together another version of the picture that was virtually identical to the film’s first cut exhibited in 1937. The re-release was as successful as its original theatrical run. The popularity and praise for Grand Illusion would flower over time as distance was put between audiences and World War II, and as the picture’s lasting, timeless themes revealed themselves. When introducing the film to a 1958 audience during the film’s re-release, Renoir said, “In 1914, man’s spirit had not yet been falsified by totalitarian religions and racism. In some respects that world war was still a war of respectable people, of well-bred people. I almost say gentlemen. That does not excuse it. Good manners, even chivalry, do not excuse a massacre.”

Fortunately, Grand Illusion features no “war is Hell” scenes of grisly trench warfare that convey the chaotic, bloody truth of battle. Neither melodrama nor jingoism has a role in Renoir’s narrative. He even carefully resists all clichés about patriotism, as well as those regarding his own pacifist aims. Renoir’s film remains politically impartial, even while he makes humanist indictments and remains a jealous disciple of his homeland. But the permanence of the film’s message resides in its humanist function regardless of borders or nationality. Watch the final scenes after Maréchal and Rosenthal have escaped their last POW stronghold, walking for days through fields and rugged terrain on their way to Switzerland. They find sanctuary on a farm occupied by a German war widow, Elsa, and her daughter, almost the only feminine presence in the film. Maréchal and Elsa have no problem communicating, though neither speaks the other’s language. They fall in love in these scenes, their affections rising above the illusion of the war. But eventually, Maréchal and Rosenthal must move on and continue on their journey through snowy mountains. As the two Frenchmen walk into the distance, a German patrol sees them but lets them go. “Forget it. They’re in Switzerland.” Had this been a Hollywood picture, the Germans would have shot. Renoir remains hopeful that even the enemy can see the absurdity of borders.

Renoir once wrote, “If a French farmer found himself dining with a French financier, those two Frenchmen would have nothing to say to each other. But if a French farmer meets a Chinese farmer they will find any amount to talk about.” These final scenes between Maréchal and Elsa demonstrate this perfectly, revealing the archetypal and transcendent humanism that brings people closer together and seeks to destroy otherwise time-honored divisions and hatred. In an even larger sense, at one point, Maréchal speaks to Elsa’s cow in French: “You were born in Wertemburg and me in Paris, but that does not prevent us understanding each other,” and seems to acknowledge the higher order of Nature. For these scenes and others throughout, Grand Illusion remains a hopeful and endearing film in search of human understanding, while also acknowledging that people are incapable of such understanding on a mass scale, resulting in war, massacre, and cultural murder. Renoir’s Naturalist Realism informs a picture that accepts the inevitability of war, yet searches through that unfathomable despair to find perhaps the most important lesson of any film in history. Renoir was a devoted believer in humanist ideals, and the film acknowledges the chimerical pursuit of connection through official borders, national reconciliation, social classes, progress, race, and hatred—all grand illusions that at once help people to organize their lives, but also separate them from each other through false perimeters and emotional prejudices. As Rosenthal states at the end of the film, “Frontiers are made by men. Nature doesn’t give a damn.”

Bibliography:

Bazin, André, and François Truffaut. Jean Renoir. Simon and Schuster, 1973.

Bergan, Ronald. Jean Renoir: Projections of Paradise. The Overlook Press, 1992.

Jackson, Julian. La grande illusion. (BFI Modern Classics). British Film Institute, 2009.

Renoir, Jean. My Life and My Films. Da Capo Press, 1991.

Sesonske, Alexandre. Jean Renoir: The French Films, 1924-1939. Harvard University Press, 1980.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review