The Definitives

Gone with the Wind (1939)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Gone with the Wind is a historical film in every sense of the word. The story, adapted from Margaret Mitchell’s beloved Pulitzer Prize-winning 1936 novel, delves into a romantic period of American history, portraying the Civil War from the losing side’s perspective. Released in 1939, this pinnacle of Golden Age filmmaking glossed over much of the setting’s inherent, problematic racial themes, not only because its sentimentalism toward the Old South comes directly from Mitchell’s novel, but because the period in which it was made was not above depicting stereotypes and ignoring certain unfortunate historical truths. The film was championed by producer David O. Selznick, who perfected the Hollywood buzz machine by making every facet of the film’s production a topic of conversation for the media and public. His efforts proved unbelievably triumphant, as his film sold more tickets than any other blockbuster before or since. It remains the most seen film in cinema history, not only because Selznick produced a monumental motion picture of immaculate quality, but because he knew how to sell it as an event. And though everything worth saying about the film has already been said or written before, we keep talking and writing about it because it demands to be remembered.

To watch the film today and be swept up in its drama and remarkable storytelling craft is not difficult, although to achieve a “pure” experience requires understanding. A viewer must transport themselves through layers of history, taking each one into account before passing judgment on a product of two distinct pasts. First, and most obviously, audiences must transport themselves to Georgia in the mid-to-late 1800s, a world vastly different than today, with views toward African Americans and women that seem archaic and wrong, but were nonetheless present in the picture’s setting. Second, one must remember that, in the South, segregation was still the law when the film was being made—that the loss of the Civil War was still an open wound in the late 1930s. With that in mind, Selznick’s production knowingly avoids any direct and certainly no hard-hitting criticisms of the South. Historical irony is not a conscious factor in the storytelling (but unconsciously); however, historical relevancy plays a major role when applying the story to a 1930s audience, its values seeded into then-modern audiences. Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett O’Hara exemplifies the modern female as she struggles for independence, but at the same time, her brazen selfishness throughout the story demands that she be put in her place. This boldfaced mixture of ideals resonated with readers of Mitchell’s novel, its appeal suited to traditionalists and progressives alike.

Still, the book’s adaptation was not a coveted studio property in 1936, just before its national publication. Old South dramas had fallen out of favor in 1930s Hollywood; not since D.W. Griffiths’ The Birth of a Nation (1915) had audiences been swept away by such an epic. MGM head Irving Thalberg scoffed at Gone with the Wind’s synopsis, famously saying “No Civil War picture ever made a nickel.” Producer David O. Selznick had more vision, however. Selznick arrived in Hollywood in 1926, finding himself a job in MGM’s story department. From there, he earned promotions at Paramount and RKO in executive and vice president roles, and later returned to MGM, all the while producing a number of box-office smashes and prestige pictures, including King Kong and Manhattan Melodrama. Ten years after arriving in Tinseltown, Selznick set up his own studio, Selznick International. And, only after every other studio in Hollywood passed on adapting Mitchell’s novel to film, was Selznick, who originally passed himself, convinced by his studio’s story editor Kay Brown to purchase the rights. He eventually read Mitchell’s book on a boat en route to Hawaii on vacation.

Still, the book’s adaptation was not a coveted studio property in 1936, just before its national publication. Old South dramas had fallen out of favor in 1930s Hollywood; not since D.W. Griffiths’ The Birth of a Nation (1915) had audiences been swept away by such an epic. MGM head Irving Thalberg scoffed at Gone with the Wind’s synopsis, famously saying “No Civil War picture ever made a nickel.” Producer David O. Selznick had more vision, however. Selznick arrived in Hollywood in 1926, finding himself a job in MGM’s story department. From there, he earned promotions at Paramount and RKO in executive and vice president roles, and later returned to MGM, all the while producing a number of box-office smashes and prestige pictures, including King Kong and Manhattan Melodrama. Ten years after arriving in Tinseltown, Selznick set up his own studio, Selznick International. And, only after every other studio in Hollywood passed on adapting Mitchell’s novel to film, was Selznick, who originally passed himself, convinced by his studio’s story editor Kay Brown to purchase the rights. He eventually read Mitchell’s book on a boat en route to Hawaii on vacation.

Selznick paid $50,000 for the rights, an unprecedented amount at the time, which led critics to call the picture “Selznick’s Folly” throughout production. The producer’s decision proved daring yet fateful, as Mitchell’s book would earn its Pulitzer in 1937 and become a best-seller with an initial 1.5 million copies sold (to date, the book has sold over 30 million copies). Of course, a notorious worrier, Selznick too had his own reservations about his purchase, but rather than show his concerns he pushed forward and treated his production as a myth-in-progress, an exhibition whose every step should be followed by fans and press alike. The book’s wild success eventually confirmed his decision: He intended to make it his most important picture yet, a grand and expensive event to which audiences would flock. The true definition of a spectacle. For this task, he would spare no expense and hire only the best talent on and offscreen. He would use three-strip Technicolor, an expensive and arduous process, and the latest cinematic technology to deliver a never-before-seen visual experience. But his vision, and its associated budget, was more than Selznick International could manage, he would learn.

Selznick’s foremost concern was casting the primary roles of Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler. Since he had purchased the rights, Mitchell’s book was becoming a public mainstay and interest swelled over the film’s production. Other studios wanted to be involved, fortunately, and would cure his overhead concerns. As an independent operation, Selznick International depended on borrowing actors contracted to the major studios. Warner Bros. offered Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Bette Davis as a package deal, while Selznick’s first instinct was for Gary Cooper as Rhett Butler. A strong push was made for Bette Davis as Scarlett (she would play a similar role in William Wyler’s Jezebel in 1939), but there was also vocal opposition. In time, both Selznick and the public agreed that the number-one box-office draw, Clark Gable, was the perfect choice for Rhett Butler, although he was contracted to MGM. Realizing Selznick needed their star as much as he needed their financial backing, Mayer loaned Gable out and in turn demanded a piece of the film, securing half of the finished film’s profits in exchange for Gable and the $1,250,000 they considered half of the budget (the picture would cost almost four times as much). Despite their investment, MGM left all creative controls to Selznick, who had the authority to deny actors like Joan Crawford and Maureen O’Sullivan who were also contract players being pushed by MGM.

On casting Scarlett, Selznick later reflected “I knew seventy-five million people would want my scalp if I chose the wrong Scarlett, and there was no agreement on who, among all the girls in pictures, was the right Scarlett.” Over the next two years, Selznick engaged himself in a nationwide casting call to find his Scarlett O’Hara. He tested 1,400 unknowns and the endeavor cost him over $100,000 at the time, but, as he later argued, the returns in publicity were “priceless”. Everyone had an opinion and it became a hot topic for Hollywood magazines. Mitchell herself voiced her picks: she wanted Miriam Hopkins, the fiery Georgia native from Trouble in Paradise as Scarlett; she also suggested Basil Rathbone as Rhett Butler. Dozens of other major actresses were auditioned, including Jean Arthur, Lucille Ball, Tallulah Bankhead, Irene Dunne, Joan Fontaine, Katharine Hepburn, Carole Lombard, Ida Lupino, Norma Shearer, Barbara Stanwyck, and others. In the end, Selznick only screen tested two performers in Technicolor: Paulette Goddard and Vivien Leigh. Selznick was advised by his publicity manager Russell Birdwell that Goddard’s scandalous and unverified marriage to Charles Chaplin would cause too much controversy, certainly more so than the equally ambiguous but less publicized relationship between Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. The latter couple had been living together after their respective spouses refused to grant them divorces. In a letter to his wife, Selznick described Leigh, a little-known actress at the time, as a “dark horse” whose striking personality and talent would exemplify Scarlett.

On casting Scarlett, Selznick later reflected “I knew seventy-five million people would want my scalp if I chose the wrong Scarlett, and there was no agreement on who, among all the girls in pictures, was the right Scarlett.” Over the next two years, Selznick engaged himself in a nationwide casting call to find his Scarlett O’Hara. He tested 1,400 unknowns and the endeavor cost him over $100,000 at the time, but, as he later argued, the returns in publicity were “priceless”. Everyone had an opinion and it became a hot topic for Hollywood magazines. Mitchell herself voiced her picks: she wanted Miriam Hopkins, the fiery Georgia native from Trouble in Paradise as Scarlett; she also suggested Basil Rathbone as Rhett Butler. Dozens of other major actresses were auditioned, including Jean Arthur, Lucille Ball, Tallulah Bankhead, Irene Dunne, Joan Fontaine, Katharine Hepburn, Carole Lombard, Ida Lupino, Norma Shearer, Barbara Stanwyck, and others. In the end, Selznick only screen tested two performers in Technicolor: Paulette Goddard and Vivien Leigh. Selznick was advised by his publicity manager Russell Birdwell that Goddard’s scandalous and unverified marriage to Charles Chaplin would cause too much controversy, certainly more so than the equally ambiguous but less publicized relationship between Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. The latter couple had been living together after their respective spouses refused to grant them divorces. In a letter to his wife, Selznick described Leigh, a little-known actress at the time, as a “dark horse” whose striking personality and talent would exemplify Scarlett.

Playwright and screenwriter Sidney Howard, who earned Oscar nominations for his adaptations of Arrowsmith in 1932 and Dodsworth in 1936, was hired to adapt Mitchell’s 1,037-page tome. His first draft was unapologetically close to the book and would have required six hours of screen time to adapt, and so, after the reclusive Howard refused Selznick’s request to leave his New England home and complete revisions on-set, Selznick took to reducing the script to a manageable size himself, with the help of frequent script doctor Ben Hecht (His Girl Friday). Selznick tasked Hecht with completing the entire rewrite in five days, having to shake the writer awake on several occasions to keep him going, keeping him on a diet of Dexedrine, bananas, and peanuts for the duration to not dull his mind with a full belly They always adapted with the concern that Mitchell’s novel was still fresh in the minds of his audience. With an adaptation of an established classic like Selznick’s production of David Copperfield, which MGM released in 1935, there was always a chance that the majority of the audience had not read the book, or at least not read it recently. Cutting whole characters or passages from a recently published novel would require careful decision-making on Selznick’s part. His choices reduced the story into an economic form, omitting plot points carefully, to avoid Mitchell’s sometimes needless repetition (Scarlett loses two children in the book; Selznick believed one was enough). Among several writers who contributed to the final script, only Howard was credited; years later, the Writer’s Guild appended the credits to acknowledge major input from Jo Swerling, Oliver H. P. Garrett, Barbara Keon, and Ben Hecht. Strangely, Selznick never received or vied for credit in spite of his vast contributions, but then, neither did any of the other handfuls of writers who provided input on the script.

By this time, three weeks of filming had already occurred under the command of director George Cuckor, with whom Selznick had collaborated on David Copperfield; Cuckor had also been involved with Gone with the Wind’s production since before casting began. Cuckor was renowned as an actresses’ director, and the story was one largely from a female perspective. He had already gained the devotion of stars Leigh and De Havilland during pre-production, but Selznick fired him in favor of Victor Fleming, who was completing work on The Wizard of Oz. The controversial decision was never fully explained at the time, although in 1947 The New York Times Magazine quoted Selznick as saying “We couldn’t see eye to eye on anything. I felt that while Cuckor was simply unbeatable in directing intimate scenes of the Scarlett O’Hara story, he lacked the big feel, the scope, the breadth of the production.” Speculation at the time suggested superstar Gable was discouraged by Cuckor’s preoccupation with female characters more than his own. In his famous memos, Selznick also suggested that Cuckor’s slow pace of completing photography fuelled his decision, as did Fleming’s experience with the complicated Technicolor process and cameras. Cuckor was not wholly opposed to the decision; he later voiced his displeasure with the revisions on Howard’s script in the subsequent years, but remained on-set to help develop the female roles as Fleming took over filming. (Incidentally, Leigh wrote to Leigh Holman, her husband at the time, that Cuckor “seems to understand the subject perfectly” and after he left, she wrote that Cuckor “was my last hope of ever enjoying the picture”). Mid-shoot, Fleming took a temporary leave due to exhaustion, during which time Sam Wood (A Night at the Opera) took over the production.

By this time, three weeks of filming had already occurred under the command of director George Cuckor, with whom Selznick had collaborated on David Copperfield; Cuckor had also been involved with Gone with the Wind’s production since before casting began. Cuckor was renowned as an actresses’ director, and the story was one largely from a female perspective. He had already gained the devotion of stars Leigh and De Havilland during pre-production, but Selznick fired him in favor of Victor Fleming, who was completing work on The Wizard of Oz. The controversial decision was never fully explained at the time, although in 1947 The New York Times Magazine quoted Selznick as saying “We couldn’t see eye to eye on anything. I felt that while Cuckor was simply unbeatable in directing intimate scenes of the Scarlett O’Hara story, he lacked the big feel, the scope, the breadth of the production.” Speculation at the time suggested superstar Gable was discouraged by Cuckor’s preoccupation with female characters more than his own. In his famous memos, Selznick also suggested that Cuckor’s slow pace of completing photography fuelled his decision, as did Fleming’s experience with the complicated Technicolor process and cameras. Cuckor was not wholly opposed to the decision; he later voiced his displeasure with the revisions on Howard’s script in the subsequent years, but remained on-set to help develop the female roles as Fleming took over filming. (Incidentally, Leigh wrote to Leigh Holman, her husband at the time, that Cuckor “seems to understand the subject perfectly” and after he left, she wrote that Cuckor “was my last hope of ever enjoying the picture”). Mid-shoot, Fleming took a temporary leave due to exhaustion, during which time Sam Wood (A Night at the Opera) took over the production.

And so, the question of authorship arises with any discussion of Gone with the Wind. Analysis of the film under the guidelines of the Auteur Theory is simply impossible, given the assortment of directors to have worked on the film’s production in various capacities, and poor record keeping that would otherwise show which director filmed which scenes. Instead, as already suggested, this film must be viewed through a historical lens, the result being a product of early Golden Age cinema—a period where the collaborative nature of cinema was at its height, where individual auteuristic drives had not yet been an established idyll, and where the producer had the influence of today’s director. Along with Hal B. Wallis and Cecil B. Demille, Selznick was among the few producers to reign over his productions and involve himself in the smallest details. This trend was less apparent in his early productions, as well as in subsequent years when his control was lost to auteur directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Carol Reed. More than any other individual involved, Selznick arranged the talent and creative forces behind this picture and shaped them to his own vision. In a very basic way, this was indeed “A David O. Selznick Picture”.

With that, Selznick’s reputation, more than that of any director or actor, was on the line during production. And even with heavily publicized production delays, casting decisions, director changes, and budgetary costs, Gone with the Wind’s reputation was, months before its release, already more popular than most films could ever hope to be. During a top-secret preview screening at Fox Theater in Riverside, California, Selznick witnessed the result of his obsessive attention to detail by allowing production details to be placed under public scrutiny. An audience expecting to see Hawaiian Nights and Beau Geste was told their double-feature would not proceed as planned, that they would be able to preview a new film before anyone else. The audience was allowed to leave before the show if they wished, but after the film began to roll the doors to the theater would be sealed for security. Once the film began to roll, the audience rumbled with the appearance of Selznick International’s logo in Technicolor and David O. Selznick’s name as producer, as most Americans knew him to be involved with the adaptation of Mitchell’s book. But when Margaret Mitchell’s name appeared onscreen, followed by the title, the audience roared with enthusiastic cheers, and suddenly all of Selznick’s doubts and deepest fears over his risky project were put to rest by the sound of applause.

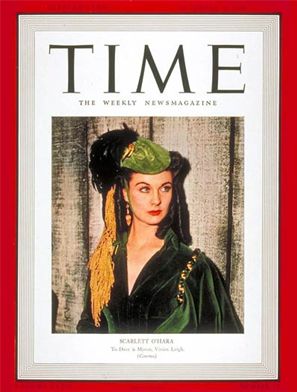

In the months following the film’s release on December 15, 1939, the same month the phenomenon of Gone with the Wind made the cover of Time magazine, critical acclaim was nothing short of fervent and audience reactions more so. In adjusted dollars, the film received nearly $3 billion in receipts and remains the most attended motion picture ever to draw audiences. Seeing the film became a worldwide event, as theaters kept the engagement running for months beyond its release date. By the 12th Annual Academy Awards banquet the following February, the few moviegoers who had not yet seen the film could rush out and see the picture, which had just won ten Oscars in almost every major category. More than the moving story or performances, Hollywood was taken by the production’s use of color. Cinematographers Ernest Haller and Ray Rennahan were the first to win an Oscar for color photography, an award created that year seemingly to celebrate this release. Production designer William Cameron Menzies took home an honorary Oscar for his use of color to enhance “dramatic mood”, while effects supervisor R.S. Musgrave received a special technical award for coordinating an innovative use of equipment on the production. Today, it is impossible to find a “Best Films” list without Gone with the Wind included. The American Film Institute’s predictable but nonetheless oft-referenced “100 Years…” series called it the fourth best film ever made, the second best romance (after Casablanca), and called “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn” the number one best line in film history.

In the months following the film’s release on December 15, 1939, the same month the phenomenon of Gone with the Wind made the cover of Time magazine, critical acclaim was nothing short of fervent and audience reactions more so. In adjusted dollars, the film received nearly $3 billion in receipts and remains the most attended motion picture ever to draw audiences. Seeing the film became a worldwide event, as theaters kept the engagement running for months beyond its release date. By the 12th Annual Academy Awards banquet the following February, the few moviegoers who had not yet seen the film could rush out and see the picture, which had just won ten Oscars in almost every major category. More than the moving story or performances, Hollywood was taken by the production’s use of color. Cinematographers Ernest Haller and Ray Rennahan were the first to win an Oscar for color photography, an award created that year seemingly to celebrate this release. Production designer William Cameron Menzies took home an honorary Oscar for his use of color to enhance “dramatic mood”, while effects supervisor R.S. Musgrave received a special technical award for coordinating an innovative use of equipment on the production. Today, it is impossible to find a “Best Films” list without Gone with the Wind included. The American Film Institute’s predictable but nonetheless oft-referenced “100 Years…” series called it the fourth best film ever made, the second best romance (after Casablanca), and called “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn” the number one best line in film history.

Beyond the film’s many awards and technical achievements (its glorious use of three-strip Technicolor and sheer lavishness behind the film’s size and production values), it remains amazing that a period drama about the Old South gathered so many moviegoers, not only on its original theatrical run, but during revivals in 1954, 1961, 1967, an unnatural “widescreen” version in 1989, and 1998. This kind of response would never happen with today’s demographic-driven viewership, where home video dominates and getting viewers out of their homes requires hundreds of millions worth of special FX, a near monopoly of science-fiction or superhero-themed yarns, not to mention a comparably less diverse director like Michael Bay or James Cameron to deliver something even as marginally successful as Gone With the Wind (which attracted more than double the audience as Cameron’s Avatar). In this sense, the film stands as the most successful ever made and the prime example to describe the term “event movie”. Moreover, today’s filmmakers too often use Selznick’s strategy of creating buzz by allowing media access to on-set production, leaving an oversaturation of behind-the-scenes information reported by countless print and web-based entertainment news outlets. Only in rare cases, such as Peter Jackson’s video diaries on his productions of The Lord of the Rings films, King Kong, and The Hobbit does this approach garner the same response. Today, the opposite approach seems to prevail, with filmmakers like Christopher Nolan and J.J. Abrams demanding secrecy on their sets, and in turn creating an effective use of mystery and marketing to intrigue, rather than inundate, their potential viewers.

And yet, looking back, the film stands as a controversial landmark for racism in cinema, one whose depictions of African Americans as slaves to the South remains troublesome and difficult to accept today. Even after he received a letter from NAACP executive Walter White protesting the representation of people of color in the film, Selznick allowed the three principal characters (Hattie McDaniel’s Mammy, Butterfly McQueen’s Prissy, and Oscar Polk’s Pork) to appear simple-minded, even contented with their status as slaves. Despite their freedom after the Civil War, for example, they never think of leaving Scarlett’s employ. According to Selznick’s memos, he believed their portrayal, and the use of the N-word, more about historical accuracy than racial prejudice. Thus, his intentions were never cruelly submitted; rather, the film’s use of the racially insensitive material is shaped by the era, a period of unquestionable ignorance that had barely begun to acknowledge African Americans as individuals (an exception being when McDaniel took home the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress). Selznick, writing to Howard about his first draft, declared “I, for one, have no desire to produce any anti-Negro film” and “I do hope that you will agree with me on this omission of what might come out as an unintentional advertisement for intolerant societies in these fascist-ridden times.” And although Selznick changed uses of the N-word to variations on “darkie” to avoid protests, the preponderance of racial stereotypes present in the final film is staggering nonetheless, and, much as with Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, the chief reason contemporary viewers may find themselves unable to appreciate Gone with the Wind’s raw cinematic value. Certainly, the film raises issues of representation and responsibility. The arguments that the film puts forth a historically accurate depiction of African Americans in the South during this time does not justify the lack of dimensionality in these characters, their apparent complicity with their own enslavement, or the romanticism given to the Old South and its slave-owning ways—complete with the juxtaposition of the Confederate flag against an ocean of fall soldiers in a famous scene meant to inspire historical patriotism for the South, an odd notion to be sure.

Though racism may cause a split among modern audiences, the story brings us together through one of the most universal themes in Mitchell’s story: sex. From the suggestive use of Technicolor to the narrative undercurrents concerning Scarlett’s romantically unfulfilled yet vivacious magnetism of men, Gone with the Wind oozes with sexuality. Informed by Mitchell’s hypochondriacal lifestyle and repressed worldview toward marriage (she once suggested putting arsenic in a husband’s soup is the only way to relieve marital boredom), the story’s sexuality becomes one of unbearable denial and delayed, rapturous gratification. Through burning colors, with a special concentration on lustful reds, Mitchell’s story progresses as willful Scarlett wears desire on her face in defiance of modesty, wielding flirtatious power over the inexperienced, doting beaus at the Wilkes’ Twelve Oaks plantation. She marries three times throughout the course of the story, and the audience waits for the sexual tension she impels to find a suitable answer—surely her desires will not be met by her shy first husband Charles Hamilton (Rand Brooks) or her aged second Frank Kennedy (Carroll Nye). Only the brash, experienced, “nasty dog” Rhett Butler can provide her with what she has so long strived for: an orgasm. Even if that means carrying her up the stairs, kicking and screaming, to give her one (in one of the film’s most precarious scenes). This is a man who looks Scarlett up and down with a suggestive gaze. “I hope to see more of you” says the man who looks at her as if he knows what Scarlett looks like out of her shimmy. “You need kissing badly. That’s what’s wrong with you,” he tells her. “You should be kissed, and often, and by someone who knows how.” Such basic desires speak to the story’s ability to reach beyond its challenging subject matter and carry an audience away as it taps into our most primal longings.

As a result, much of Gone with the Wind’s success can be attributed to simply being the right film released at the right time, a conflicted coming-of-age story for the modern woman from the perspective of Scarlett: an immature flirt who, finally, becomes a woman who knows what she wants. Surrounded by the Southern airs of her character’s era, Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett O’Hara may seem lusty and willful and snobbish, defiant of authority, and unquestionably superficial by nature. Her character is in opposition to De Havilland’s kindhearted Melanie Hamilton, a selfless human being whose nobility contains the heart of the story, as through her we realize how awful Scarlett’s behavior can be. But Scarlett’s headstrong ways also lead to her economic autonomy with her own cotton and lumber businesses, and most importantly her disregard for the male-dominated world—notions important to the modern woman of the 1930s who faced struggles against their sex every day, always with the hope that “tomorrow is another day”. Yet, as much as modernity plays a major role in the film’s success, tradition plays an equally significant one. Scarlett’s selfishness, her endless pursuit of Leslie Howard’s Ashley Wilkes, motivates atrocious behavior on her part, and despite her admirable sovereignty in a male-dominated world, there remains a desire to see her put in her place. Why else would the film end with Gable’s Rhett Butler, in perhaps the most memorable line in film history, telling her, “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” With that, he confirms that the more the world changes, the more it stays the same. And so, indeed, Scarlett’s fight must go on.

As a result, much of Gone with the Wind’s success can be attributed to simply being the right film released at the right time, a conflicted coming-of-age story for the modern woman from the perspective of Scarlett: an immature flirt who, finally, becomes a woman who knows what she wants. Surrounded by the Southern airs of her character’s era, Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett O’Hara may seem lusty and willful and snobbish, defiant of authority, and unquestionably superficial by nature. Her character is in opposition to De Havilland’s kindhearted Melanie Hamilton, a selfless human being whose nobility contains the heart of the story, as through her we realize how awful Scarlett’s behavior can be. But Scarlett’s headstrong ways also lead to her economic autonomy with her own cotton and lumber businesses, and most importantly her disregard for the male-dominated world—notions important to the modern woman of the 1930s who faced struggles against their sex every day, always with the hope that “tomorrow is another day”. Yet, as much as modernity plays a major role in the film’s success, tradition plays an equally significant one. Scarlett’s selfishness, her endless pursuit of Leslie Howard’s Ashley Wilkes, motivates atrocious behavior on her part, and despite her admirable sovereignty in a male-dominated world, there remains a desire to see her put in her place. Why else would the film end with Gable’s Rhett Butler, in perhaps the most memorable line in film history, telling her, “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” With that, he confirms that the more the world changes, the more it stays the same. And so, indeed, Scarlett’s fight must go on.

Of course, though gender assignments and sexuality play intuitive roles in the film, the sweeping production fulfills both our intellectual and emotional desires by way of pure visual spectacle. The evacuation of Atlanta alone required thousands of extras, all seen as the camera, rising to capture the rushing horde, frames the scene without ever losing Scarlett. When Atlanta later burns, flames mount to enclose silhouettes of Rhett guiding the carriage through chaos, framing an image that could almost be mistaken for rotoscope animation. Or take the recurring composition where the camera pulls back on a foreground silhouette to reveal a middle layer matte painting, most often of Tara, the O’Hara family plantation, and a background photograph of an impossibly blazing sky, all sounding in unison with Max Steiner’s score. Used not only to denote the passage from one chapter to the next, this shot also closes out the film with a certain grandiose classicism. And then the colors, bright and prosperous pastels in the opening barbeque sequence, but then more complicated with rich, deep colors, deeper shadows, and a substance into the image itself as the story progresses. Not unlike The Adventures of Robin Hood released just one year before, colors and their increasingly high contrasts throughout make viewing Gone with the Wind an experience of color as it relates to emotion in service of the story, and one augmented all the more with Technicolor.

In the 1930s, the type of filmmaking on display in Gone with the Wind was achieved through collaboration and artistic altruism, a defining characteristic of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Truly inspired, Selznick brought Mitchell’s sweeping narrative to magnificent life by wielding his era’s often selfless devotion to pure storytelling, whereby any and all technical means were employed to transport an audience away to another time and place, the cinematic atmosphere determined by the story’s far-reaching romantic breadth. An embodiment of that approach in its most extravagant form, the film’s historical importance cannot be denied, even if within there reside regrettable truths about the era it represents and the period it was made. Hollywood has never seen a film as commercially booming or as universally flocked to, and no doubt there will never be another attended with such an incredible response from the general public. Gone with the Wind is a monument of cinema that continues to incite impassioned discussions of relevancy, racial ignorance, sexual politics, and technical showmanship. Whatever the point of view, this is a film that will not be ignored. Its influence and popularity signify everything that is both majestic and problematic about early Hollywood filmmaking. Yet, like its heroine, all of the film’s faults, along with its wonderful flourishes, survive as an unapologetic time capsule that must be admired for its resilience.

In the 1930s, the type of filmmaking on display in Gone with the Wind was achieved through collaboration and artistic altruism, a defining characteristic of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Truly inspired, Selznick brought Mitchell’s sweeping narrative to magnificent life by wielding his era’s often selfless devotion to pure storytelling, whereby any and all technical means were employed to transport an audience away to another time and place, the cinematic atmosphere determined by the story’s far-reaching romantic breadth. An embodiment of that approach in its most extravagant form, the film’s historical importance cannot be denied, even if within there reside regrettable truths about the era it represents and the period it was made. Hollywood has never seen a film as commercially booming or as universally flocked to, and no doubt there will never be another attended with such an incredible response from the general public. Gone with the Wind is a monument of cinema that continues to incite impassioned discussions of relevancy, racial ignorance, sexual politics, and technical showmanship. Whatever the point of view, this is a film that will not be ignored. Its influence and popularity signify everything that is both majestic and problematic about early Hollywood filmmaking. Yet, like its heroine, all of the film’s faults, along with its wonderful flourishes, survive as an unapologetic time capsule that must be admired for its resilience.

Bibliography:

Behlmer, Rudy. Memo from David O. Selznick. New York: Modern Library, 2000.

Haskell, Molly. Frankly, My Dear: ‘Gone with the Wind’ Revisited. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Mitchell, Margaret. Gone with the Wind. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1936.

Molt, Cynthia Marylee. Gone with the Wind on Film: A Complete Reference. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1990.

Myrick, Susan. White Columns in Hollywood: Reports from the GWTW Sets. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press, 1982.

Pratt, William. Scarlett Fever. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1977.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review