The Definitives

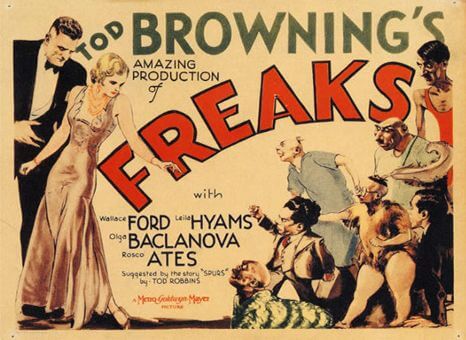

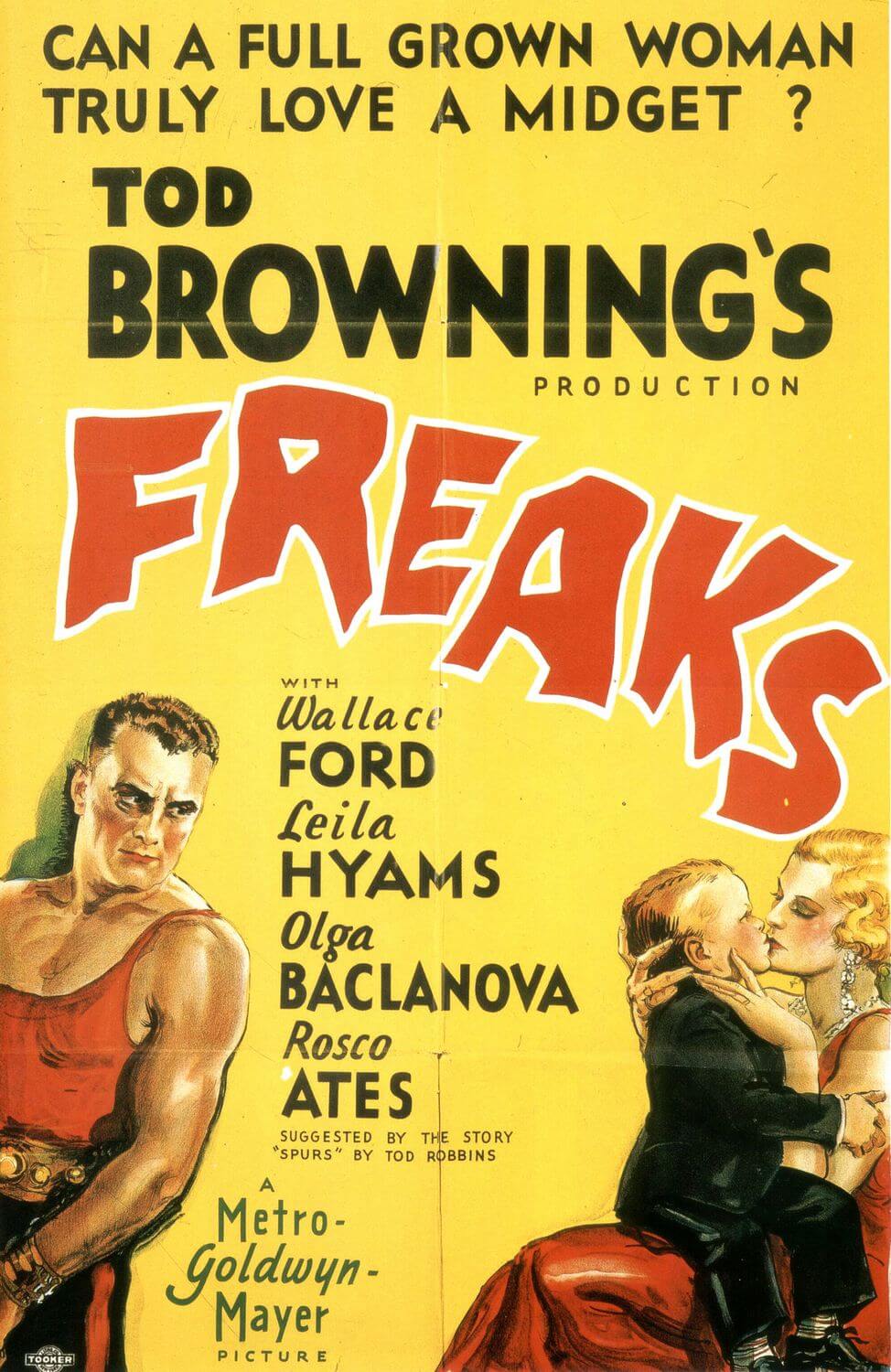

Freaks (1932)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Tod Browning’s Freaks endures as one of the strangest curiosities ever put to celluloid, a film that tests our initial repulsion and challenges our basic human sympathies. Released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1932 before Hays Code censorship laws were widely enforced, the film presents a sordid melodrama and morality play set around circus sideshow performers, all played by authentic “freaks” of the era—everyone from dwarves to conjoined twins to “The Human Torso” make appearances. As a carnival barker might announce, No makeup was used to create these fascinating deformities!, although in this case, the claim is true. Audiences and critics shunned the film for showcasing actual abnormalities of nature, and it was in some cases banished for decades after its release. Browning, a member of several circuses in his early years, sought to surpass the horrors of Dracula, his classic released the previous year; yet, he also wanted to humanize his atypical performers. His clashing, problematic ambitions resulted in a film that explores our darkest nightmares and then shames us for feeling terrified or appalled. And for many viewers, the nightmare was far too real to categorize as escapism.

Regarded as the “Edgar Allen Poe of cinema”, Browning explored the macabre in his films, tales in which physical grotesqueries represent an elusive inner disorder. For critic and historian Stuart Rosenthal, who wrote the first scholarly consideration of the director’s work in 1975, Browning’s attraction to such themes followed almost “compulsive” drives. These themes were evident onscreen, and so often implemented that they are seemingly interchangeable from film to film. And yet, in Freaks, that formula is turned upside-down by populating his film with sideshow attractions, all contrasted by a beautiful “normal” woman whose murderous vanity reflects her personal ugliness. Of course, the freaks have their violent retribution as well, but they are not villains or horrible people, rather honest and trusting individuals living by a strict code—“offend one and offend them all”. Only a few studies of Browning have been conducted from a critical-biographical standpoint, and none during his lifetime. He rarely talked about his work in film, but went on at length about his years as a circus performer. In interviews conducted toward the end of his life, Browning related varying accounts of his history, all filled with half-truths and embellishments one would almost expect from a former carnie, yet all with some basis in fact.

Browning’s entertainment career began in vaudeville, where he learned the magic trade from illusionists like Alexander “Herrmann the Great”, who taught Browning tricks he would later use in his movies. In 1888, Browning performed in black face at the bottom of a pit as a “barking wild man” for the Manhattan Fair and Carnival Company. His act changed frequently, later becoming “Bosco the Snake Eater” in a geek role. For Ringling Bros., he played a clown, handcuff escape artist, contortionist, and ringmaster. But his most famous role would be as a “living hypnotic corpse”, an act in which he was buried alive in a ventilated coffin (images undoubtedly used later for Dracula) and left underground for 48 hours from Friday to Sunday. The act was a wild success, especially when played on Easter. Before he arrived in Hollywood, Browning organized a burlesque show in New York called The Wheel of Mirth on a successful year-long run. It was there he met D.W. Griffith and performed in a number of nickelodeon comedies for the director. In 1913, Griffith moved to Hollywood. Browning followed, acted in several films including Griffith’s Intolerance, and learned the cinema trade. By 1915, Browning had directed his first short, The Lucky Transfer, for Reliance-Majestic, followed by twisted titles like The Spell of the Poppy, The Living Death, and The Burned Hand all the same year.

Browning’s entertainment career began in vaudeville, where he learned the magic trade from illusionists like Alexander “Herrmann the Great”, who taught Browning tricks he would later use in his movies. In 1888, Browning performed in black face at the bottom of a pit as a “barking wild man” for the Manhattan Fair and Carnival Company. His act changed frequently, later becoming “Bosco the Snake Eater” in a geek role. For Ringling Bros., he played a clown, handcuff escape artist, contortionist, and ringmaster. But his most famous role would be as a “living hypnotic corpse”, an act in which he was buried alive in a ventilated coffin (images undoubtedly used later for Dracula) and left underground for 48 hours from Friday to Sunday. The act was a wild success, especially when played on Easter. Before he arrived in Hollywood, Browning organized a burlesque show in New York called The Wheel of Mirth on a successful year-long run. It was there he met D.W. Griffith and performed in a number of nickelodeon comedies for the director. In 1913, Griffith moved to Hollywood. Browning followed, acted in several films including Griffith’s Intolerance, and learned the cinema trade. By 1915, Browning had directed his first short, The Lucky Transfer, for Reliance-Majestic, followed by twisted titles like The Spell of the Poppy, The Living Death, and The Burned Hand all the same year.

A devastating car crash in 1915 left Browning without teeth, his body all but broken and permanently hobbled, and his rampant alcohol dependency enhanced by related, constant physical pain. Within years, Browning had a director’s position at Universal Studios, where he met longtime collaborators actor Lon Chaney (“The Man of a Thousand Faces”) and studio head Irving Thalberg. During his prolific run of studio chillers, he was sacked from Universal when he tossed his false teeth at a hotel manager, shouting “Go bite yourself!” In his ongoing back-and-forth between MGM and Universal, Browning made ten pictures with Chaney, including The Unholy Three (1925), a tale about a group of circus performers-turned-robbers, featuring Chaney as a ventriloquist in grandma drag, Harry Earles (of the famous “Doll Family”) as a dwarf disguised as a child, and their strongman assistant (Victor McLaglen). His greatest success came in 1931 with Dracula, the iconic adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel, wherefrom he and star Bela Lugosi established immortal vampire tropes in cinema.

With the success of Dracula at Universal, MGM offered Browning an adaptation of Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin, which he declined in order to develop the Tod Robbins short story Spurs at MGM, about a circus sideshow, first published in Munsey’s Magazine in February 1923. Years earlier, Browning had convinced the studio to purchase the story’s film rights for $8 thousand after Harry Earles recommended it. Perhaps Thalberg, his own body generally frail and sickly, identified with a story about the humanity behind an “ugly” exterior, as he personally took over the writers’ development started by Browning in 1927. Writers Willis Goldbeck and Elliot Clawson were assigned at Browning’s request, but Thalberg oversaw their progress, and in the case of the film’s ending, demanded that changes be made. Browning wanted a dramatic end to humanize the “freak” subjects and deliver a melodramatic finish, whereas Thalberg sought a more macabre tone—an ending very much in line with most Browning films, which so often conclude with a twist or horrific revenge.

The screen story involves duplicitous trapeze artist Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova) seducing sideshow midget Hans (Earles) for his inheritance. Hans’ reluctant friends, the other sideshow attractions, resist allowing her into their clan, until Hans maintains her love is genuine. Finally they are married, and at the reception the freaks admit Cleopatra, chanting their ritualized initiation: “Gooble-goble, gooble-goble! …We accept her! …One of us, one of us!” Drunk at the ceremony, Cleopatra reveals her true feelings, insults the freaks, and tosses wine in their faces; her affair with strong man Hercules (Henry Victor) becomes apparent as they kiss in front of everyone. After, the lovelorn Hans remains with his new wife, though she slowly poisons him. Performer Venus (Leila Hyams) overhears Cleopatra expounding her plot to run away with Hans’ money after his death and tells the others. That rainy, storming night on the road, the freaks band together by Hans’ orders, crawling through the mud with knives in their mouths and weapons in their hands. They cut up Hercules and chase Cleopatra into the woods, reforming her body through mutilation into that of a “Human Duck”—her sideshow title, as a ringmaster informs onlookers in the last scene where Cleopatra is shown on display at the bottom of a pit, squawking and legless.

The screen story involves duplicitous trapeze artist Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova) seducing sideshow midget Hans (Earles) for his inheritance. Hans’ reluctant friends, the other sideshow attractions, resist allowing her into their clan, until Hans maintains her love is genuine. Finally they are married, and at the reception the freaks admit Cleopatra, chanting their ritualized initiation: “Gooble-goble, gooble-goble! …We accept her! …One of us, one of us!” Drunk at the ceremony, Cleopatra reveals her true feelings, insults the freaks, and tosses wine in their faces; her affair with strong man Hercules (Henry Victor) becomes apparent as they kiss in front of everyone. After, the lovelorn Hans remains with his new wife, though she slowly poisons him. Performer Venus (Leila Hyams) overhears Cleopatra expounding her plot to run away with Hans’ money after his death and tells the others. That rainy, storming night on the road, the freaks band together by Hans’ orders, crawling through the mud with knives in their mouths and weapons in their hands. They cut up Hercules and chase Cleopatra into the woods, reforming her body through mutilation into that of a “Human Duck”—her sideshow title, as a ringmaster informs onlookers in the last scene where Cleopatra is shown on display at the bottom of a pit, squawking and legless.

Thalberg originally wanted Myna Loy as Cleopatra and Jean Harlow as Venus, but as Browning’s start date approached it became apparent that the director’s employment of actual physically deformed stars could stir up unwanted reactions, and so Thalberg kept his major stars away. Casting director Ben Piazza scouted East Coast sideshows for a month to find only the best talent, sending pictures back to Hollywood for Browning to approve. Piazza found a surplus of carnival performers; among those rejected were an “elephant skinned” girl, a boy with dog legs, a tattooed man, a “giant”, a whole team of pygmies, and a renowned midget performer known as Major Mite. Browning hand-picked the individuals who appear in the film: Koo Koo (“the bird girl from Mars”) suffered from the rapid aging disease called Progeria; the torso of Johnny Eck (real name Johnny Eckhart) ended below his rib cage; Olga Roderick was the resident bearded lady; Prince Randian had no arms or legs but could roll and match-light a cigarette using only his mouth; the pinhead Schlitze (real name Simon Metz) led a whole group of his kind (victims of Microcephaly, more commonly known as pinheads; in the circus they were called “the missing link” and were sometimes associated with Australian or Aztec cultures); and Betty Green (“the stork woman”), who suffered from no anomalies, but opted to use her supreme unattractiveness as a gimmick. Also appearing are two armless women, a human skeleton, a “turtle girl”, a sword swallower, a hermaphrodite, and others.

What Browning and his crew discovered was that, typically, each sideshow has one genuinely deformed performer, such as conjoined twins, a bearded lady, pinheads, etc. All the rest are “normal” people in costume as padding for the authentic main event. But when Browning chose a whole cast’s worth of true freaks, he found each one was accustomed to being the star of their show, and thus each one behaved like a prima donna on set. Rather than forming a bond from their shared maladies during production, their egos clashed. Browning told a reporter later that the freaks’ “professional jealousy was amazing. Not one of them had a good word for the other.” They were proud and vain, more aghast by the other freaks’ physical maladies than their own. Several began wearing sunglasses and acting like movie stars, although most would never appear on celluloid again. Despite their egos, shooting proceeded without much incident in terms of publicity, except when producer Harry Rapf insisted that the freaks eat in a separate mess hall “so people could get to eat in the commissary without throwing up.” Rapf’s comments seemed harsh until F. Scott Fitzgerald, near the end of an MGM screenwriting gig, was joined in the commissary for lunch by the famed conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton and lost his lunch (he recounted the incident in his story Crazy Sundays). Resulting from their treatment, as well as their representation and later reactions to the film, many of the performers involved would regret appearing in the film.

What Browning and his crew discovered was that, typically, each sideshow has one genuinely deformed performer, such as conjoined twins, a bearded lady, pinheads, etc. All the rest are “normal” people in costume as padding for the authentic main event. But when Browning chose a whole cast’s worth of true freaks, he found each one was accustomed to being the star of their show, and thus each one behaved like a prima donna on set. Rather than forming a bond from their shared maladies during production, their egos clashed. Browning told a reporter later that the freaks’ “professional jealousy was amazing. Not one of them had a good word for the other.” They were proud and vain, more aghast by the other freaks’ physical maladies than their own. Several began wearing sunglasses and acting like movie stars, although most would never appear on celluloid again. Despite their egos, shooting proceeded without much incident in terms of publicity, except when producer Harry Rapf insisted that the freaks eat in a separate mess hall “so people could get to eat in the commissary without throwing up.” Rapf’s comments seemed harsh until F. Scott Fitzgerald, near the end of an MGM screenwriting gig, was joined in the commissary for lunch by the famed conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton and lost his lunch (he recounted the incident in his story Crazy Sundays). Resulting from their treatment, as well as their representation and later reactions to the film, many of the performers involved would regret appearing in the film.

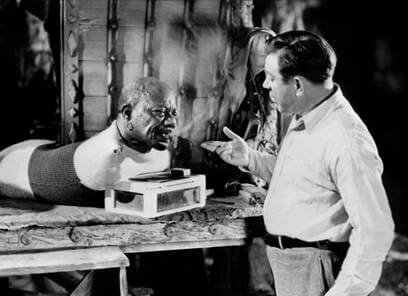

But Browning was careful to keep the production’s progress quiet, having a deep respect for his extraordinary cast. Whether from his days in the circus or sympathy for individuals with physical deformities like his own, Browning accepted the freaks and felt at home around them, even at their worse. A number of the performers proved to be unpredictable. “Once in a while they became upset,” Browning told an interviewer, “and would try to vent their rage in biting the person nearest to them. I was bitten once.” Then again, some like Schlitze were even-tempered and well-behaved; Schlitze, a bright and joyous personality onscreen, even gained the esteem of studio actress Norma Shearer. Regardless of their behavior, Browning loved the deformed performers and being around them; he befriended many of them, the half-man Johnny Eck above all (Eck was known to ride the camera dolly with the director). As evident in his films, particularly those with Chaney, Browning enjoyed oddity in both a psychological and physical sense. But Chaney became grotesque with movie makeup; these performers’ deformities were real, and so Browning loved them all the more.

Browning’s behavioral caused more problems with the crew than his colorful cast, however. Editor Basil Wrangell called Browning “a sadist” whose erratic behavior disrupted everyone on set. Always demanding and curtly shouting orders, Browning was known to bellow and throw things, behaving cruelly toward the crew while treating the freaks with delicate consideration. This might be interpreted as an act for the freaks’ sake, but few of Browning’s productions were completed without some questionable behavior on his part. Crewmembers would later call him “a bastard” and “pitiless” toward production staff; Browning’s alcoholism was believed to have fuelled these rages. But there was always a notion that Browning was an outsider; he led a private life, and kept his friends close and everyone else at a distance. After receiving reports from the set not only about the freaks’ behavior but Browning’s, Mayer demanded that the production be shut down. Thalberg refused and fought Mayer to keep the cameras rolling and Browning in the director’s chair. During the production of Freaks, Browning’s behavior was well known throughout Hollywood and the film’s eventual commercial failure would lead to his virtual expulsion from cinema.

Browning’s behavioral caused more problems with the crew than his colorful cast, however. Editor Basil Wrangell called Browning “a sadist” whose erratic behavior disrupted everyone on set. Always demanding and curtly shouting orders, Browning was known to bellow and throw things, behaving cruelly toward the crew while treating the freaks with delicate consideration. This might be interpreted as an act for the freaks’ sake, but few of Browning’s productions were completed without some questionable behavior on his part. Crewmembers would later call him “a bastard” and “pitiless” toward production staff; Browning’s alcoholism was believed to have fuelled these rages. But there was always a notion that Browning was an outsider; he led a private life, and kept his friends close and everyone else at a distance. After receiving reports from the set not only about the freaks’ behavior but Browning’s, Mayer demanded that the production be shut down. Thalberg refused and fought Mayer to keep the cameras rolling and Browning in the director’s chair. During the production of Freaks, Browning’s behavior was well known throughout Hollywood and the film’s eventual commercial failure would lead to his virtual expulsion from cinema.

Having developed his talents in the Silent Era of Hollywood, Browning was one of several artists left behind by the emergence of sound. Though he made several talkies, his reliance on title cards (such as the intertitle “The Wedding Feast”) to mark transitions remained in Freaks and, for many critics, would mark his deficient, un-modern approach. In its day, this was an almost retro, certainly unfashionable motion picture placed awkwardly between the silent and sound eras, as Browning was never wholly confident in his application of the new sound device. Shot almost like a silent picture, Browning left the editor to sort out how the overlapping, unsynchronized chants during the wedding scene would be reconciled. But Browning’s failure to embrace the technical end of sound gives way to one of the film’s most dynamic characteristics, its dependence on powerful images. He arranges shots with a concentration on their composition and the camera’s movements, as opposed to their aural depth. During the wordless, breathless climactic storm sequence, the photography is so confident that images burn into our brain, only to later haunt our nightmares.

Production wrapped on Freaks around Christmas of 1931. At a preview screening in January 1932, reports of viewers running from the auditorium foreshadowed the larger public’s reactions. As a result, the studio cut Freaks from one-and-a-half hours to just barely over an hour. Among the scenes cut was a comic relief moment where the “turtle girl” is chased by an enamored seal; an epilogue set in “Tetrallini’s Freak and Music Hall”; an alternative “happy” ending (recently reincorporated into the film on home video); Hercules singing falsetto after his castration by the freaks; and shots of muddy freaks hog piling Cleopatra. The new studio cut debuted nationally on February 10 and lasted two weeks in most areas. All over the country, and beyond, reactions were extreme. A judge in Atlanta deemed it illegal according to the city’s laws on decency. When the film opened in Washington D.C., Mrs. Ambrose Nevin Diehl, committee head for the film division of the National Association of Women, wrote to William H. Hays (as in Hays Code) and demanded the film be pulled from the state’s theaters. Not only was Mrs. Diehl reviled by the depiction of the abnormalities onscreen, but also the film’s unabashed sexual innuendos. In one scene, Cleopatra asks Hercules, “Feel like eating something?” He asks for the eggs in her wagon, and then she opens her robe, her frame on display, and says, “How do you like them?” Other theaters simply refused to book it.

Production wrapped on Freaks around Christmas of 1931. At a preview screening in January 1932, reports of viewers running from the auditorium foreshadowed the larger public’s reactions. As a result, the studio cut Freaks from one-and-a-half hours to just barely over an hour. Among the scenes cut was a comic relief moment where the “turtle girl” is chased by an enamored seal; an epilogue set in “Tetrallini’s Freak and Music Hall”; an alternative “happy” ending (recently reincorporated into the film on home video); Hercules singing falsetto after his castration by the freaks; and shots of muddy freaks hog piling Cleopatra. The new studio cut debuted nationally on February 10 and lasted two weeks in most areas. All over the country, and beyond, reactions were extreme. A judge in Atlanta deemed it illegal according to the city’s laws on decency. When the film opened in Washington D.C., Mrs. Ambrose Nevin Diehl, committee head for the film division of the National Association of Women, wrote to William H. Hays (as in Hays Code) and demanded the film be pulled from the state’s theaters. Not only was Mrs. Diehl reviled by the depiction of the abnormalities onscreen, but also the film’s unabashed sexual innuendos. In one scene, Cleopatra asks Hercules, “Feel like eating something?” He asks for the eggs in her wagon, and then she opens her robe, her frame on display, and says, “How do you like them?” Other theaters simply refused to book it.

MGM launched a defensive campaign to spin the film as a deeply human story, rather than a monstrous exploitation film. Borrowing cues from The Merchant of Venice, ads called for understanding. Headlines read “What about abnormal people? They have their lives, too!” and continued “Have they no right to love?” (If you prick them, do they not bleed?)Rare praise came from gossip columnist Louella O. Parsons and critic Charles E. Lewis of the Motion Picture Herald, but their minority opinions faded into the milieu of angry, offended reactions. The preponderance of critics lambasted the film. John C. Moffitt of the Kansas City Star wrote, “It took a weak mind to produce it and it takes a strong stomach to look at it.” The Atlanta Journal said the film “transcends the fascinatingly horrible, leaving the spectator appalled.” Richard D. Watts, Jr. of the New York Herald-Tribune wrote, “it is obviously an unhealthy and generally disagreeable work.” Pulled from circulation in most areas, Great Britain went the furthest and banned the film for the next thirty years.

In all, Freaks cost MGM around $315 thousand and the film lost $165 thousand. Browning remained baffled by the reaction into his last days. He never understood that its reality—the appearance of people distorted not by Hollywood effects but by Nature—was too much for mainstream audiences. George Mitchell Jr., a Silent Era reader for Universal, once remarked that “we all like to see ugly things… We are all attracted, to a certain extent, to that which is hideous. But when it passes a certain point, the attraction dies and we suffer a feeling of repulsion and nausea.” This seems to be what happened with audiences in 1932, many the same viewers who lauded the monstrosity and morbidity behind Dracula the previous year.Browning’s career would never recover from this blow, having pushed his audiences too far. His films, such as The Unholy Three, had tested audiences before, but as they were profitable his risks were justified. Hollywood viewed this as an utter failure on Browning’s part. After Freaks was released, Browning tried to develop a picture in which Eck could star, a tale about surgical experimentation, but it never panned out. Studios refused to fund a Browning project, especially one involving bodily disfigurement, sideshows, or even commercial horror. He made only a handful of films after Freaks. His last picture, about an illusionist, was called Miracles for Sale and was released in 1939. Browning officially retired to Malibu in 1942 and became a recluse; he died in 1962 at the age of 82.

In all, Freaks cost MGM around $315 thousand and the film lost $165 thousand. Browning remained baffled by the reaction into his last days. He never understood that its reality—the appearance of people distorted not by Hollywood effects but by Nature—was too much for mainstream audiences. George Mitchell Jr., a Silent Era reader for Universal, once remarked that “we all like to see ugly things… We are all attracted, to a certain extent, to that which is hideous. But when it passes a certain point, the attraction dies and we suffer a feeling of repulsion and nausea.” This seems to be what happened with audiences in 1932, many the same viewers who lauded the monstrosity and morbidity behind Dracula the previous year.Browning’s career would never recover from this blow, having pushed his audiences too far. His films, such as The Unholy Three, had tested audiences before, but as they were profitable his risks were justified. Hollywood viewed this as an utter failure on Browning’s part. After Freaks was released, Browning tried to develop a picture in which Eck could star, a tale about surgical experimentation, but it never panned out. Studios refused to fund a Browning project, especially one involving bodily disfigurement, sideshows, or even commercial horror. He made only a handful of films after Freaks. His last picture, about an illusionist, was called Miracles for Sale and was released in 1939. Browning officially retired to Malibu in 1942 and became a recluse; he died in 1962 at the age of 82.

In subsequent years, Freaks became fodder for cult movie screenings at midnight horror festivals after being re-released at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival, the appeal not unlike an actual sideshow, watched for the sheer peculiarity put on display. Today, the film has garnered some esteem as a controversial and must-see picture from the Pre-Code era, but it remains a curiosity nonetheless. Tonally, an audience can never seem to reconcile if Browning’s film is pure horror or a melodrama staged around sideshow characters. Browning may not have known himself, as he calls for humanization of the seemingly inhuman freaks, and yet he dwells on their maladies like a sideshow gawker, at times reducing the picture to exploitative voyeurism. And certainly the almost comic treatment of the conclusion’s “Human Duck” trivializes any pure dramatic intentions, delivering an ending on par with your average Tales from the Crypt horror story. But reducing the picture to a mere horror film would be a mistake, despite the sideshow guise. The difference between this and say, The Human Centipede movies (a series in which audiences are meant to watch a freakish physical abomination), remains Browning’s incomparable humanism, even in the distorted face of the revenge scheme.

The truth about Freaks is that it fails to function on one level—horror or drama—alone, although Browning hoped it would humanize the “freaks” of his film for mainstream audiences, portraying what is different as beautiful, just as Bela Lugosi humanized the vampire in Dracula or Lon Chaney humanized his varied grotesque characters. Still, Freaks is much more than simply a filmic sideshow with human oddities on display for the masses to point at and ridicule, and much more complicated than a one-note horror yarn. The film operates on multiple planes, reviling some viewers and engrossing others. Through a variety of incongruous themes and several shortcomings, the film endures, begging to be watched again and again. No matter how you react to the film, you will react. But unlike today’s provocateur directors trying to test the limits of censorship with gore and makeup, Browning sews together our natural fear of what is different with a real human drama through the misshapen exterior of his characters, who, of course, are humans too. In turn, he may not have achieved all of his cinematic aspirations with this film, but he created something unforgettable that could not and will not ever be matched or replicated; our politically correct world would simply never allow it. For that, we must savor Freaks as a genuine rarity about all that is ugly and beautiful about being human.

The truth about Freaks is that it fails to function on one level—horror or drama—alone, although Browning hoped it would humanize the “freaks” of his film for mainstream audiences, portraying what is different as beautiful, just as Bela Lugosi humanized the vampire in Dracula or Lon Chaney humanized his varied grotesque characters. Still, Freaks is much more than simply a filmic sideshow with human oddities on display for the masses to point at and ridicule, and much more complicated than a one-note horror yarn. The film operates on multiple planes, reviling some viewers and engrossing others. Through a variety of incongruous themes and several shortcomings, the film endures, begging to be watched again and again. No matter how you react to the film, you will react. But unlike today’s provocateur directors trying to test the limits of censorship with gore and makeup, Browning sews together our natural fear of what is different with a real human drama through the misshapen exterior of his characters, who, of course, are humans too. In turn, he may not have achieved all of his cinematic aspirations with this film, but he created something unforgettable that could not and will not ever be matched or replicated; our politically correct world would simply never allow it. For that, we must savor Freaks as a genuine rarity about all that is ugly and beautiful about being human.

Bibliography:

Rosenthal, Stuart. Tod Browning. London: Tantivy Press, 1975.

Savada, Elias; Skal, David J. Dark Carnival: The Secret World of Tod Browning, Hollywood’s Master of the Macabre. New York: Anchor Books, 1995.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review