The Definitives

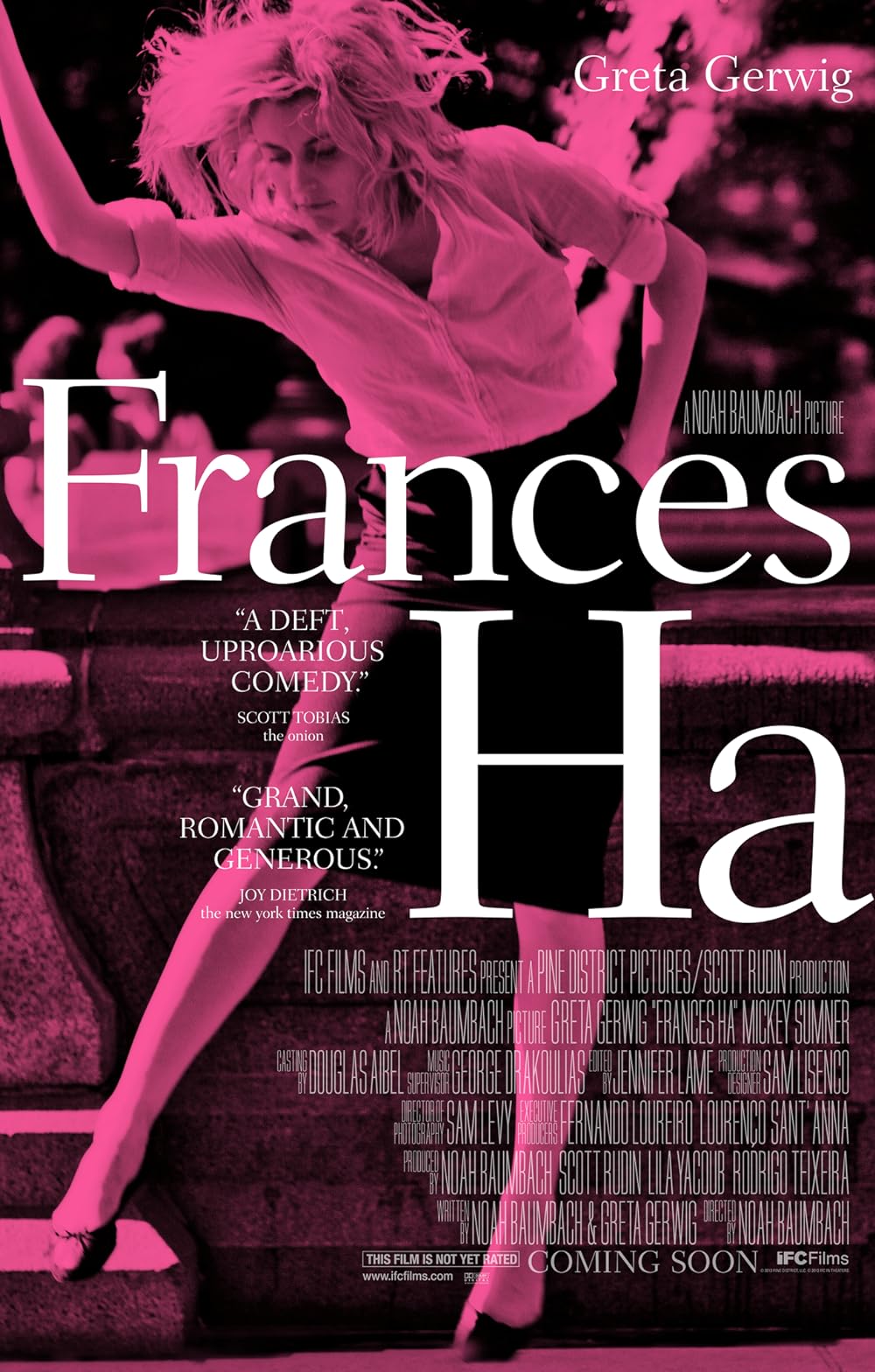

Frances Ha (2013)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha is a love story, but the rarest kind of love story. Though filmed in black-and-white, it’s anything but. Baumbach’s film doesn’t feature a protagonist who finds the companion of her dreams, nor are there a marriage or a grandiose confession of adoration in the climactic scene. There are no meet-cutes or elaborate romantic setups. Baumbach’s muse Greta Gerwig stars as Frances, a young woman in her late twenties with boundless charm but no sense of moderation. She lives in New York City alongside other casually stylish, drifting characters, on whom she relies for a sense of purpose, despite resounding feelings of disappointment and unworthiness. She’s an energetic, talented person, but she’s never been a success, despite her obvious gifts as a ballet choreographer. Perhaps Gerwig’s vulnerable Frances seems a little mad, given her thorough lack of restraint and dreamily romantic expectations for the world; regardless, she’s self-aware enough to acknowledge her imperfections. Eventually anyway. Much of Baumbach’s sense of joy throughout Frances Ha resides in Gerwig’s infectious charisma, and her character’s spiritual awakening of sorts, her self-discovery. Instead of a typical love story, Frances Ha is about Frances falling for someone who was right in front of her all along: herself.

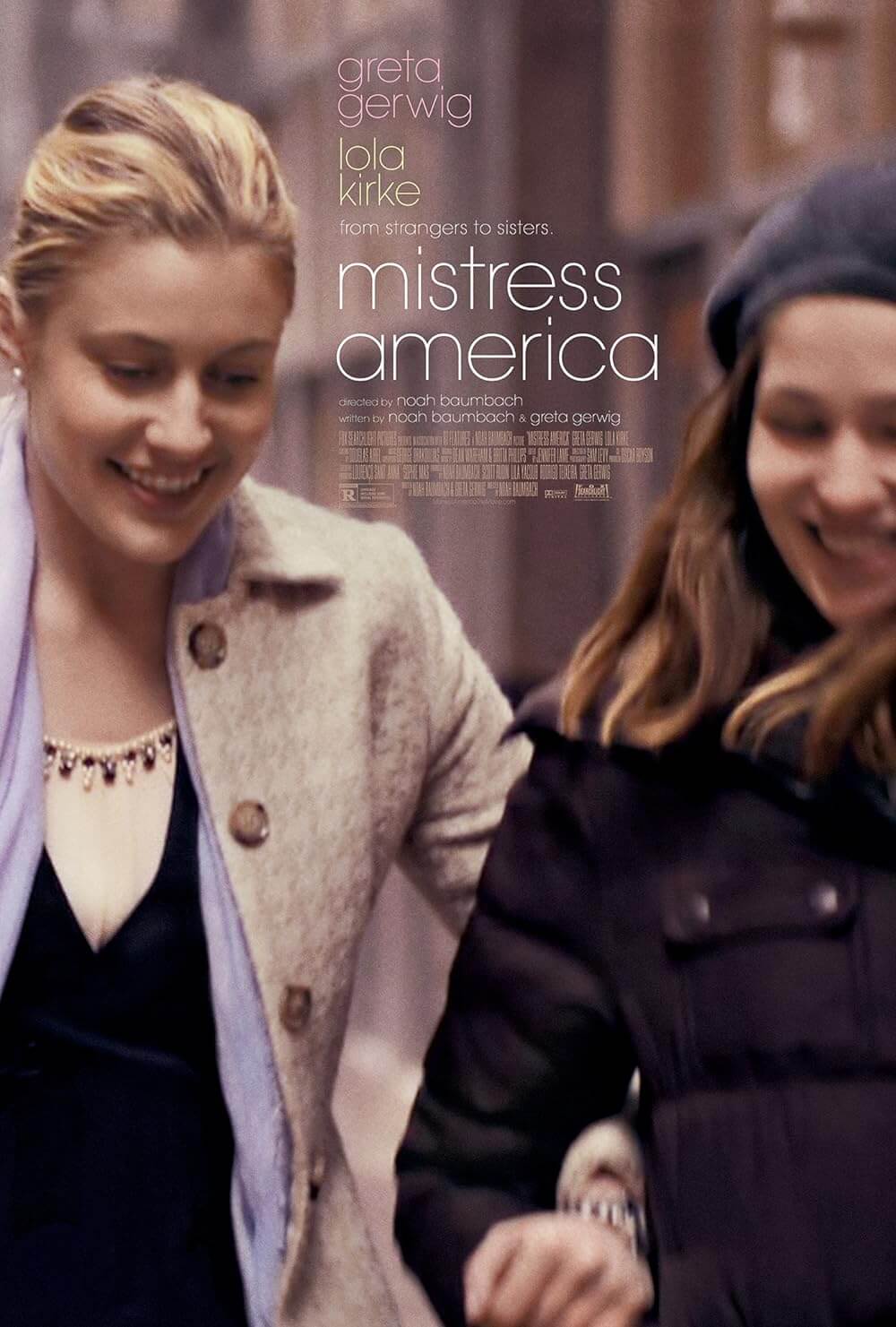

Like many Baumbach pictures, Frances Ha considers middle-class uncertainty. His films are often about people who struggle to leave their youth behind. His first film was Kicking and Screaming (1995), about a group of college graduates who refuse to engage their futures. In some way or another, that theme of self-consciously avoiding the inevitable future has pervaded throughout every subsequent film to his name. Nobody wants to grow up in Baumbach’s films. A Brooklyn native born from writer Jonathan Baumbach and critic Georgia Brown, Baumbach grew up a cinéphile in a family of film enthusiasts. His parents’ divorce stuck with him and shaped his depiction of several father-figures; he later co-wrote The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004) and Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) with writer-director Wes Anderson, both films about talented fathers who undervalue their sons. But it took another ten years for Baumbach the filmmaker to reach his stride. 2005 brought The Squid and the Whale, his semi-autobiographical take on his parents’ divorce and its effect on his family. In addition to earning him an Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay, the film also launched Baumbach’s career into a prolific period. He followed it with Margot at the Wedding in 2007, a film about neuroses held over from youth; then Greenberg in 2010, about a fortysomething narcissist who experiences a younger generation. While We’re Young and Mistress America were both released in 2015, each about relatively older people looking back on their earlier twenties.

However, Baumbach’s best effort remains Frances Ha, which he co-wrote with its star. Gerwig received her start in the films of mumblecore director Joe Swanberg, LOL in 2006 and Hannah Takes the Stairs in 2007. She followed them with Jay and Mark Duplass’ excellent Baghead from 2008. She first teamed with Baumbach in Greenberg, playing Florence, a woman tired from her own casual sex relationships. “I have to stop doing things just because they feel good,” Florence says in that introspective, bemused way Gerwig often delivers her lines. She “has a specific way of delivering her most impassioned points,” observed writer Liz Pelly, “where her typically slow-moving, stoned-sounding vocal inflection swells into wide-eyed declarations, dreamy but definitive, long-winded and full of heart.” Her unique, insightful charm has led her to work alongside filmmakers like Woody Allen, Whit Stillman, Todd Solondz, and Mike Mills. Gerwig is more than just an enchanting onscreen personality; she’s worked as a writer, too, since early in her career. Her co-directorial effort, Nights and Weekends, was made alongside Swanberg in 2008. After Greenberg, she worked with Baumbach, her romantic partner, twice more on Frances Ha and Mistress America. Gerwig told Dazed magazine in an interview about their 2015 film, “When you’re writing a screenplay, it’s like you’re dreaming the film for yourself again and again and again until it becomes almost like a memory before you make it.” Undoubtedly this approach fuels Gerwig’s onscreen naturalism.

However, Baumbach’s best effort remains Frances Ha, which he co-wrote with its star. Gerwig received her start in the films of mumblecore director Joe Swanberg, LOL in 2006 and Hannah Takes the Stairs in 2007. She followed them with Jay and Mark Duplass’ excellent Baghead from 2008. She first teamed with Baumbach in Greenberg, playing Florence, a woman tired from her own casual sex relationships. “I have to stop doing things just because they feel good,” Florence says in that introspective, bemused way Gerwig often delivers her lines. She “has a specific way of delivering her most impassioned points,” observed writer Liz Pelly, “where her typically slow-moving, stoned-sounding vocal inflection swells into wide-eyed declarations, dreamy but definitive, long-winded and full of heart.” Her unique, insightful charm has led her to work alongside filmmakers like Woody Allen, Whit Stillman, Todd Solondz, and Mike Mills. Gerwig is more than just an enchanting onscreen personality; she’s worked as a writer, too, since early in her career. Her co-directorial effort, Nights and Weekends, was made alongside Swanberg in 2008. After Greenberg, she worked with Baumbach, her romantic partner, twice more on Frances Ha and Mistress America. Gerwig told Dazed magazine in an interview about their 2015 film, “When you’re writing a screenplay, it’s like you’re dreaming the film for yourself again and again and again until it becomes almost like a memory before you make it.” Undoubtedly this approach fuels Gerwig’s onscreen naturalism.

Gerwig and Baumbach’s writerly collaborations are about complicated women coming into their own. “In A Room of One’s Own,” Gerwig observed, “Virginia Woolf talks about how men can’t write about what women do alone because they’re not there. That’s the world that I feel some ability to report back on.” Like Gerwig, her character in Frances Ha grew up in Sacramento and moved to Brooklyn. Frances is twenty-seven and underemployed as an apprentice at a dancing company. After college, she moved in with Sophie (Mickey Sumner), her best friend with whom she shares everything. This is the kind of friendship Gerwig was talking about, a relationship between women alone. Frances and Sophie are the most connected plutonic couple imaginable. One of the film’s many excellent montages shows them play-fighting, eating, watching TV, smoking, and lying in bed together—their relationship summed up in a few precise shots. “We’re the same person,” Frances likes to say of Sophie. When Frances’ boyfriend asks her to move in with him, she declines and breaks up with him, not wanting to separate from Sophie. It makes it all the more tragic when Sophie casually drops that she’s not going to renew their lease, so she can instead move into a long-desired Tribeca apartment with a different friend. There’s nothing worse than discovering your friends like you less than you originally thought. After this blow, Frances endures several passages where she runs out of money, loses her job, and moves a number of times (her various addresses appear on title cards and act like chapters throughout the film).

Frances’ quarter-life crisis at the center of this film explores how a person moves beyond their twenties, sets aside their former young self, and finds a new version of themselves to support. For Frances, it means eliminating the practical worries that fill her current, disorganized life. There’s also her personality to consider. She can behave like an overgrown child, consuming dinner conversations and missing cues to shut up. She makes rash, thoughtless decisions and never apologizes for them. She refers to people and events as magical (“I’ll bet it’s magic,” she says of Paris), like a child who still believes in unicorns and fantasy tales. After Sophie leaves, Frances rents a room with two “rich boy” hipsters, Lev (Adam Driver) and Benji (Michael Zegen). Benji jokingly calls her “undateable” for how she lives in her idiosyncratic headspace. Somehow, Frances seems to know she’s destined for greatness, and her overwhelming misery throughout Frances Ha cannot shatter her sense of entitlement—the feeling that her supportive parents and journey to New York have somehow made her insusceptible to failure. At the same time, Frances masks herself behind an infectious smile and the playful, blithe physicality that is Gerwig’s bouncy onscreen presence.

Frances’ quarter-life crisis at the center of this film explores how a person moves beyond their twenties, sets aside their former young self, and finds a new version of themselves to support. For Frances, it means eliminating the practical worries that fill her current, disorganized life. There’s also her personality to consider. She can behave like an overgrown child, consuming dinner conversations and missing cues to shut up. She makes rash, thoughtless decisions and never apologizes for them. She refers to people and events as magical (“I’ll bet it’s magic,” she says of Paris), like a child who still believes in unicorns and fantasy tales. After Sophie leaves, Frances rents a room with two “rich boy” hipsters, Lev (Adam Driver) and Benji (Michael Zegen). Benji jokingly calls her “undateable” for how she lives in her idiosyncratic headspace. Somehow, Frances seems to know she’s destined for greatness, and her overwhelming misery throughout Frances Ha cannot shatter her sense of entitlement—the feeling that her supportive parents and journey to New York have somehow made her insusceptible to failure. At the same time, Frances masks herself behind an infectious smile and the playful, blithe physicality that is Gerwig’s bouncy onscreen presence.

Shot for a mere $3 million under an inconspicuous working title (Untitled Digital Workshop), Baumbach used Frances Ha as a platform for Gerwig’s talent. “Greta has old studio-system chops,” Baumbach told an interviewer. “They could sing, they could dance. [Frances Ha] was intended to be a showcase for her to do a lot of this.” Once again shooting in New York, Baumbach, ever a cerebral and literate filmmaker, channels several established filmmakers into his own innovative style. Although Frances Ha received, and deserves, many comparisons to the more artistic work of Woody Allen (The New Yorker said Baumbach “seems to have made his Manhattan“), the director’s stylistic influence remains French New Wave filmmakers such as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, and Éric Rohmer. Like these filmmakers in their New Wave prime, Baumbach shoots in actual locations using little-known actors. Amid entries by Harry Nilsson and Hot Chocolate, much of Frances Ha’s soundtrack borrows from French film composer Georges Delerue, who wrote the music for Truffaut’s Jules and Jim (1962) and Godard’s Contempt (1963), among dozens of other scores. Sam Levy shoots with digital cameras, but the monochrome cinematography looks grainy and soft like celluloid. Compositionally, Levy and Baumbach combine intimate, natural close-ups with master shots that give us a broader picture of a scene.

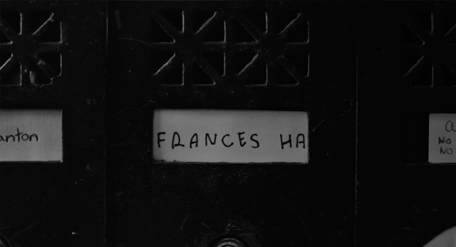

Other references to the French New Wave are less obvious and might only be caught by cinéphiles. Not that a viewer must be versed in New Wave titles to appreciate Frances Ha; rather, it works its charms without any foreknowledge of Baumbach’s stylistic concerns. They simply inform the material and establish its place in the ongoing train of influence in cinema. After all, the French New Wave, and every subsequent New Wave movement in countries from Great Britain to Poland, was a film movement of youthful filmmakers rebelling against the classical style of their elders. New Wave films often involve youthful characters carving out a piece of the world for themselves, even if it means rejection and solitude. Individualism is the center of countless French New Wave titles. Truffaut’s classic The 400 Blows comes to mind, in which Jean-Pierre Léaud’s Antoine Doinel struggles through adolescence. Truffaut continued to follow Doinel into adulthood in the short Antoine and Collette (1962), and then three feature-length sequels Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed and Board (1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Even Frances Ha’s title has its origins in the New Wave. Frances’ last name remains unspoken throughout the film; we finally see it abridged, because she wrote it too big on the mailbox label in her first solo apartment. In Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in U.S.A. (1966), we never learn the last name of the protagonist’s ex-lover Richard; whenever his last name is mentioned, the sound is blocked out by car horns or a ringing telephone. He’s simply known as “Richard Pa—”.

Other references to the French New Wave are less obvious and might only be caught by cinéphiles. Not that a viewer must be versed in New Wave titles to appreciate Frances Ha; rather, it works its charms without any foreknowledge of Baumbach’s stylistic concerns. They simply inform the material and establish its place in the ongoing train of influence in cinema. After all, the French New Wave, and every subsequent New Wave movement in countries from Great Britain to Poland, was a film movement of youthful filmmakers rebelling against the classical style of their elders. New Wave films often involve youthful characters carving out a piece of the world for themselves, even if it means rejection and solitude. Individualism is the center of countless French New Wave titles. Truffaut’s classic The 400 Blows comes to mind, in which Jean-Pierre Léaud’s Antoine Doinel struggles through adolescence. Truffaut continued to follow Doinel into adulthood in the short Antoine and Collette (1962), and then three feature-length sequels Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed and Board (1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Even Frances Ha’s title has its origins in the New Wave. Frances’ last name remains unspoken throughout the film; we finally see it abridged, because she wrote it too big on the mailbox label in her first solo apartment. In Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in U.S.A. (1966), we never learn the last name of the protagonist’s ex-lover Richard; whenever his last name is mentioned, the sound is blocked out by car horns or a ringing telephone. He’s simply known as “Richard Pa—”.

In addition to Baumbach’s references to the New Wave, the director employs a number of fantastic, technically brilliant montages. Compilations of brief shots carry the audience through a period in Frances’ life. On a Christmas trip back to Sacramento, we see brief glimpses of Frances’ parents greeting her at the airport with the family dog in arms; she and her mother decorate the Christmas tree; she takes the dog for a walk with her dad; she visits the dentist; she meets up with old friends; she reconnects with extended family at a holiday party; and finally, her parents, dog in arms, return her to the airport. Montages communicate a wealth of information about Frances and, though Frances Ha runs a mere 86 minutes, add to the considerable depths of feeling and dimensionality of the character. Among the most heartbreaking montages is a sequence where, though she doesn’t have any money, Frances recklessly charges a weekend to France. She sleeps away half the first day from jet lag. She tries to meet up with a friend, Abby, who lives in Paris, but can’t get her on the phone, leaving several voicemails. After walking around Paris quite uneventfully for a day-and-a-half, Frances comes home. On the cab back to her apartment, she listens to a voicemail from Abby, who sounds excited to hear from Frances, says they should have dinner, and she wants to set Frances up with a friend who looks like Jean-Pierre Léaud. At this, Frances does not react. Her dream of visiting Paris did not go as planned; that could be said of everything in her life at this point.

In her earlier, extreme-low-budget indie days, Gerwig was celebrated for her natural performances; she could act like she was not acting. This brings to mind the scene in Frances Ha when someone asks her, “What do you do?” She responds, “It’s kind of hard to explain.” “Because what you do is complicated?” “Because I don’t really do it,” she replies, almost with pride. Gerwig doesn’t seem to be acting in Baumbach’s films so much as inhabiting. Her naturalness brings Frances to life on an emotional level, but also a comic one. Indeed, her often dialogue-driven roles outside of Baumbach’s films rarely afford her the chance to demonstrate her knack for physical comedy. Though she studied philosophy and acting, Gerwig’s early interest in dance comes through in Frances Ha, where she’s seen running down the streets of New York to David Bowie’s “Modern Love” or performing ballet movements as a dance company apprentice. There’s a great moment when she runs to get cash at the end of a date. The shot follows her from the street, until suddenly Frances falls behind a car. All at once, Frances gets up again and keeps running, now with a little limp. One of Gerwig’s funniest onscreen moments is in Mistress America, where she descends the red steps near the TKTS Discount Booths in Times Square. A snapshot of the scene makes her look like a celebrity, but she takes her time to carefully maneuver every step, making a potentially magnificent moment hilariously awkward.

In her earlier, extreme-low-budget indie days, Gerwig was celebrated for her natural performances; she could act like she was not acting. This brings to mind the scene in Frances Ha when someone asks her, “What do you do?” She responds, “It’s kind of hard to explain.” “Because what you do is complicated?” “Because I don’t really do it,” she replies, almost with pride. Gerwig doesn’t seem to be acting in Baumbach’s films so much as inhabiting. Her naturalness brings Frances to life on an emotional level, but also a comic one. Indeed, her often dialogue-driven roles outside of Baumbach’s films rarely afford her the chance to demonstrate her knack for physical comedy. Though she studied philosophy and acting, Gerwig’s early interest in dance comes through in Frances Ha, where she’s seen running down the streets of New York to David Bowie’s “Modern Love” or performing ballet movements as a dance company apprentice. There’s a great moment when she runs to get cash at the end of a date. The shot follows her from the street, until suddenly Frances falls behind a car. All at once, Frances gets up again and keeps running, now with a little limp. One of Gerwig’s funniest onscreen moments is in Mistress America, where she descends the red steps near the TKTS Discount Booths in Times Square. A snapshot of the scene makes her look like a celebrity, but she takes her time to carefully maneuver every step, making a potentially magnificent moment hilariously awkward.

Normally in cinema, a character such as Frances remains the quirky, attractive oddball (what Gerwig calls a “manic pixie dream girl”) that attracts the attentions of a bland working stiff (think Something Wild, Jonathan Demme’s 1986 comedy). But Baumbach and Gerwig explore this character type to the fullest, and completely avoid turning Frances into an object for the benefit of a male character. Late in the film, Benji appears at her dance performance. Their living together early on, their slight flirtations, and their meeting at random at one point mid-film suggest that she and Benji will end up together in typical romantic comedy fashion. Instead, they share a moment where both characters admit they’re “undateable” (so of course they should get together). But instead of realizing the obviousness of their potential union in a predictable rom-com moment, the scene cuts. It cuts to Frances looking across the room at Sophie in the same way she describes earlier at a dinner party: “It’s when you’re at a party but you’re both talking to other people and you’re laughing and shining and you look across the room and catch each other’s eyes.” That’s love. Except now, it’s a love Frances has let go of, in a way. She has moved on and found her own definition of success. It’s not that Frances is really immune to failure, but she learns that the standard definitions of terms like success and failure come with expectations for life, and instead of living with expectations, Frances resolves to simply live.

If there’s an appropriate genre for Frances Ha, it must be bildungsroman, a German word meaning “education” and “book”, specifically as they relate to an individual. Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield is an example; Lena Dunham’s Tiny Furniture (2010) or her HBO show Girls are others. In many ways, Dunham’s work and Baumbach’s film have much in common, as both could be described as existential stories about hipsters; but such a label (given the sometimes negative connotations with hipsters) does the great joys of these stories an injustice. To be sure, Frances receives a spiritual education in the film. Though she hardly remains an optimist, she commits everything to the moment at hand. When she runs down the street dancing to “Modern Love”, there’s nothing more than that moment, and it’s beautiful. Frances Ha is a love story, but “It really [has] nothing to do with men at all,” Gerwig noted. It’s about finding internal harmony. After Frances’ dance performance in the last scenes, we see her not glowingly happy with the miraculous-movie-magic-way things turned out for her. Much like Antoine Doinel in the iconic last scene of The 400 Blows, we see a character braced and contented for the uncertainty life will thrust upon her. However bittersweet and terribly real this insight is for Frances, Baumbach and Gerwig have turned it into something endearing and unforgettable.

If there’s an appropriate genre for Frances Ha, it must be bildungsroman, a German word meaning “education” and “book”, specifically as they relate to an individual. Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield is an example; Lena Dunham’s Tiny Furniture (2010) or her HBO show Girls are others. In many ways, Dunham’s work and Baumbach’s film have much in common, as both could be described as existential stories about hipsters; but such a label (given the sometimes negative connotations with hipsters) does the great joys of these stories an injustice. To be sure, Frances receives a spiritual education in the film. Though she hardly remains an optimist, she commits everything to the moment at hand. When she runs down the street dancing to “Modern Love”, there’s nothing more than that moment, and it’s beautiful. Frances Ha is a love story, but “It really [has] nothing to do with men at all,” Gerwig noted. It’s about finding internal harmony. After Frances’ dance performance in the last scenes, we see her not glowingly happy with the miraculous-movie-magic-way things turned out for her. Much like Antoine Doinel in the iconic last scene of The 400 Blows, we see a character braced and contented for the uncertainty life will thrust upon her. However bittersweet and terribly real this insight is for Frances, Baumbach and Gerwig have turned it into something endearing and unforgettable.

Bibliography:

Baker, Annie. “Frances Ha: The Green Girl.” Criterion.com. November 12, 2013.

Brody, Richard. “Frances Ha and the Pursuit of Happiness.” NewYorker.com. May 15, 2013.

Larson, Sarah. “Noah Baumbach, Kicking and Screaming Into Middle Age.” NewYorker.com. September 2, 2015.

Pelly, Liz. “Greta Gerwig Gets Real.” Dazed.com. October, 2015.

Scott, A.O. “If 27 Is Old, How Old Is Grown Up?” NYTimes.com. May 16, 2013.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review