The Definitives

Foreign Correspondent

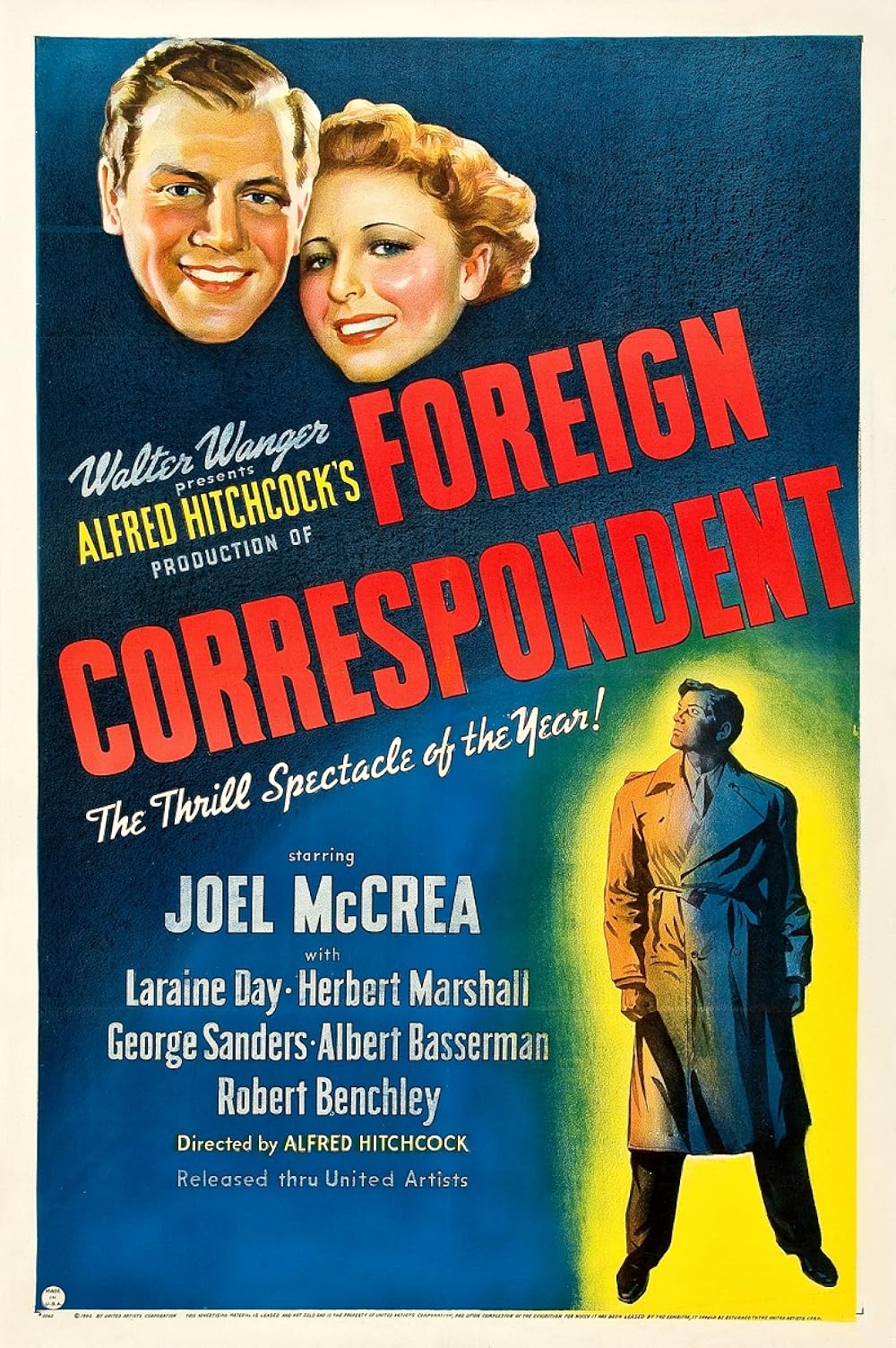

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Foreign Correspondent is about a world caught up in the rumors, mounting tension, politicized repression, and uncertainty that preceded World War II. Alfred Hitchcock’s wartime conspiracy thriller makes the director’s most pronounced statement against the looming threat of Nazi Germany. Released in 1940, the film is a smartly crafted and often funny Hollywood spy yarn assembled by the crowned Master of Suspense, featuring breakneck pacing and some of the most memorable sequences in the director’s career. Nominated for six Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Visual Effects, it could easily serve as two hours of pure escapism. Except mining the film next to other Hitchcock thrillers of the era reveals a political undercurrent that recontextualizes the director’s earlier entertainments, uncovering a vein of Hitchcock’s patriotism and anti-Nazi commentary. What follows is a historical and thematic overview that aims to situate Foreign Correspondent as a bold call to action to stop the looming threat of Nazism in Europe. By exploring how Hitchcock used the spy-thriller genre throughout the 1930s as a platform to identify Nazi Germany and fascism as a threat, and further, speak against isolationist interests in the US, the film can be seen as more than simply escapism but an entrenched anti-Nazi statement by a seemingly apolitical filmmaker.

Long before Hollywood began openly inserting anti-Nazi messages into their films after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the US mobilization, the British film industry tried to convince the US to join the war effort. Their tactics resembled those of later Hollywood wartime cinema, ranging from subtle commentaries to outright pleas for help from their American allies to overt anti-Nazi sentiments. In many cases, their messages represented the first time moviegoers in the United States had been exposed to any anti-Nazi texts—whether textual or subtextual—in a film. The spy-thrillers made by Alfred Hitchcock between 1934 and 1940, released in the United States by either a major Hollywood distributor or a British distributor with a significant presence in the US market, showed the situation in Europe. The films portray their contemporary Europe as teeming with foreign agents and conspiracies, often by using Germans as the villains of the story, and in doing so, establishing a fixed cinematic trope of Nazi villainy. Hitchcock’s spy-thrillers, and those influenced by his 1930s work, instilled a sense of paranoia in the viewing audience. Who could be trusted today? Nazis could be anywhere, anyone. Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, the director’s first spy-thriller produced by Hollywood and an explicitly anti-Nazi film, reveals how the director’s earlier work also contained anti-Nazi messages and influenced other filmmakers and studios to make anti-Nazi spy pictures.

But first, a word about the relationship between Hollywood and the British film industry before the Second World War—complicated and often spiteful but a fiscally necessary arrangement. Hollywood had a stake in the British market since the 1920s, but US films dominated British screens with sometimes 95 percent of the market. With less interest in British film, the UK film industry declined, and its studios struggled to establish a vertically integrated industry that could compete with the major Hollywood studios. The British government responded with the Cinematograph Films Acts of 1927 and 1938, which attempted to minimize the number of US titles in British theaters and grow the local industry by creating exhibition and production mandates. At the same time, Hollywood tried to stabilize their own place in the British market and established offices in England. Warner Bros., Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and Twentieth Century-Fox each put production units in England that either helped produce British films or purchased completed films for distribution.

After Hitler took power, British cinemas were quick to react and portray the potential threat of another world war. By September 3, 1939, when the British and French governments declared war on Germany, the British Ministry of Information had an active Film Division headed by Jack Beddington. Beddington was an advertising executive for the oil industry charged with making films aimed at British audiences to inspire the nation and maintain a positive outlook during the war. Many of the titles produced by Beddington focused on the working-class women in the audience, a demographic that justified the British government keeping the country’s over 4,000 movie theaters open for business. Titles like Brian Desmond Hurst’s A Call For Arms! (1940), for instance, centered on a pair of showgirls who set aside stripping to work in a munitions factory, portraying how every citizen, no matter their background, could help in the war effort. Other films blended patriotism with the lives of everyday homemakers, mothers, and the otherwise overlooked female audience. Meanwhile, many studios—including Alexander Korda’s London Film Productions, the Rank Organisation, and Denham Film Studios—sought to bolster the public without state influence.

After Hitler took power, British cinemas were quick to react and portray the potential threat of another world war. By September 3, 1939, when the British and French governments declared war on Germany, the British Ministry of Information had an active Film Division headed by Jack Beddington. Beddington was an advertising executive for the oil industry charged with making films aimed at British audiences to inspire the nation and maintain a positive outlook during the war. Many of the titles produced by Beddington focused on the working-class women in the audience, a demographic that justified the British government keeping the country’s over 4,000 movie theaters open for business. Titles like Brian Desmond Hurst’s A Call For Arms! (1940), for instance, centered on a pair of showgirls who set aside stripping to work in a munitions factory, portraying how every citizen, no matter their background, could help in the war effort. Other films blended patriotism with the lives of everyday homemakers, mothers, and the otherwise overlooked female audience. Meanwhile, many studios—including Alexander Korda’s London Film Productions, the Rank Organisation, and Denham Film Studios—sought to bolster the public without state influence.

Alfred Hitchcock worked outside the Ministry of Information’s purview in the arena of popular entertainment. Indeed, Hitchcock was a well-known director in the United States long before David O. Selznick coaxed him over the Atlantic in 1939. In 1927, in response to the decline of the British film industry, an exhibitor named John Maxwell orchestrated a merger with the failing British National Studios to reorganize and create a new company, British International Pictures, commonly called B.I.P. The primary exports of B.I.P. from 1927 to 1932 were the films of their highest-paid and most popular director, Hitchcock, with titles such as Blackmail (1929), Murder! (1930), and The Skin Game (1931) that thrilled both British and US audiences. After his deal with B.I.P. ended, Hitchcock teamed with the Gaumont-British Picture Corporation, the British offshoot of the French company Gaumont Pictures, owned by the brothers Isidore and Maurice Ostrer. Hitchcock’s string of seven films under Gaumont-British began in 1934 and, in most cases, responded to the European aggressions that posed a potential threat to the British.

In his book The Star-Spangled Screen: The American World War II Film, Dick Bernard writes that more than a third of the anti-Nazi films in the pre-Pearl Harbor era feature some manner of spies or espionage activity—a regular fixture in fiction after the First World War, complete with yarns about assassination attempts, sabotage, germ warfare, and stealing top-secret military plans. Filmmakers and writers could not help but notice historical parallels to the events preceding the Great War. With Hitler’s governmental takeover, Nazi Germany’s aggressive actions throughout Europe, and a botched assassination attempt on President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, the world certainly seemed to be heading down a familiar path. Newspaper headlines about the rise of fascism across Europe only added to an uneasiness permeating through the UK about what Germany would do next. Spies could be anywhere and anyone. They could be your trusted colleague, a friend, your neighbor, even your husband. For Hitchcock, the dramatic possibilities were endless. Watching a good yarn about British people thwarting the nefarious activities of foreign spies became a popular method of entertainment during this period, as they provided a necessary catharsis to settle social and political tensions.

Hitchcock isn’t usually associated with political filmmaking. Film scholars rank him in the pantheon of cinema’s great art as entertainment directors, capable of infusing his sharp craft and wit into meticulously designed thrillers. Hitchcock loved spy stories because of their effortless ability to create tension within his audience. Spy scenarios could carry their characters into elaborate plots, allowing for multiple locations, set pieces, and thrilling chases. Hitchcock and his writers just needed a MacGuffin to drive the material. As Hitchcock explained to François Truffaut in his famous series of interviews, a MacGuffin is nothing more than “the device, the gimmick” that sets the spies into motion. The MacGuffin is the thing everyone wants, tries to possess, tries to know, or tries to stop. It validates the action of the plot and conflicts within the story, though its specificity remains at once unimportant yet vital. Hitchcock’s MacGuffin disguises the essential—but also entirely pointless—question of why the proceedings occur. The answer to this question in many of Hitchcock’s films between 1934 and 1940 is the same: the Nazis want the MacGuffin to enable their evil plans.

Hitchcock isn’t usually associated with political filmmaking. Film scholars rank him in the pantheon of cinema’s great art as entertainment directors, capable of infusing his sharp craft and wit into meticulously designed thrillers. Hitchcock loved spy stories because of their effortless ability to create tension within his audience. Spy scenarios could carry their characters into elaborate plots, allowing for multiple locations, set pieces, and thrilling chases. Hitchcock and his writers just needed a MacGuffin to drive the material. As Hitchcock explained to François Truffaut in his famous series of interviews, a MacGuffin is nothing more than “the device, the gimmick” that sets the spies into motion. The MacGuffin is the thing everyone wants, tries to possess, tries to know, or tries to stop. It validates the action of the plot and conflicts within the story, though its specificity remains at once unimportant yet vital. Hitchcock’s MacGuffin disguises the essential—but also entirely pointless—question of why the proceedings occur. The answer to this question in many of Hitchcock’s films between 1934 and 1940 is the same: the Nazis want the MacGuffin to enable their evil plans.

Hitchcock’s first spy-thriller during this period was The Man Who Knew Too Much, released in 1934 and inspired by “Bulldog Drummond’s Baby,” a story about Britain’s heroic gentleman adventurer Bulldog Drummond, a popular series on the radio and in print. If there was a heroic British everyman thwarting evil during this era, chances are Bulldog Drummond inspired him. Hitchcock and his team of writers adapted the material by removing both Drummond and the baby of the title, leaving a scenario about distressed parents trying to track down their kidnapped child. While traveling to Switzerland, British couple Bob (Leslie Banks) and Jill Lawrence (Edna Best) witness the killing of their friend, French skier Louis Bernard (Pierre Fresnay). With his dying breath, Bernard tells them where to locate a secret message in his hotel room (the MacGuffin) that must be received by the British consul. Bob locates the secret message detailing a plot to assassinate a foreign dignitary in London. But the Lawrences learn a group of German-accented spies kidnapped their adolescent daughter and threaten to kill her should they speak to anyone about the information contained in the message. Working to recover their daughter without official help, Bob sleuths the location of the spies, while Jill prevents the assassination by interrupting a concert at the Albert Hall—where a cymbal crash would drown out the assassin’s gunshot—with a scream. The film’s climactic scene involves a lengthy shootout with police, followed by Jill using her skills as a competitive sharpshooter to save her daughter.

The Man Who Knew Too Much contains many allusions to Germany through its plotting in Europe and its surface details; though, the film never specifically mentions Nazis or Adolf Hitler. Hitchcock’s use of actor Peter Lorre as the film’s central, scar-faced villain cannot be ignored. The Hungarian-born actor received his start on the Berlin stage and advanced to international acclaim when he appeared as a child murderer in the internationally renowned German film M (1931), directed by Fritz Lang. After fleeing Hitler’s Germany in 1933, Lorre stopped in London on his way to a monumental career in Hollywood, lending his slithering presence to Abbott, the cackling spy in The Man Who Knew Too Much. Audiences familiar with Lorre would no doubt associate him with Germany; though the spies’ country of origin goes unspecified in the film, their German accents and prominent use of Luger pistols make the implication clear. Moreover, in an early scene, a British secretary of the Foreign Office tries to implore the Lawrences to tell all they know about the assassination plot. “Why should we care if some foreign statesman we never heard of were assassinated?” asks Bob, thinking of his daughter’s safety. The secretary replies, “Tell me, in June 1914, had you ever heard of a place called Sarajevo? Of course you hadn’t. I doubt if you ever heard of the Archduke Ferdinand. But in a month’s time, because a man you never heard of killed another man you never heard of, in a place you never heard of, this country was at war.” By establishing a parallel between the impetus of the First World War and the current rumblings in Europe in 1934, Hitchcock furthers anxiety, fear, paranoia, and alertness to his country’s present political situation.

Professionally, Hitchcock avoided speaking out against fascism or talking politics, leading many to believe Hitchcock’s films contained no political motivations whatsoever. But many of his collaborators at Gaumont-British belonged to anti-fascist groups such as the British Committee for Victims of German Fascism. Take Charles Bennett, one of Hitchcock’s chief writers at Gaumont-British, who contributed to nearly every screenplay during the director’s 1930s period. Years later in the 1940s, Bennett worked with the British Ministry of Information to write pure propaganda films. Bennett had a close relationship with Hitchcock as a primary contributor to screen scenarios, along with the director’s often uncredited wife Alma Reville, and together their ideas were inspired by newspaper headlines, books, and plays. It was Bennett who suggested that Hitchcock adapt John Buchan’s 1915 novel The Thirty-Nine Steps, a First World War spy yarn whose title refers to the steps that lead to the secret headquarters of a German spy organization.

Professionally, Hitchcock avoided speaking out against fascism or talking politics, leading many to believe Hitchcock’s films contained no political motivations whatsoever. But many of his collaborators at Gaumont-British belonged to anti-fascist groups such as the British Committee for Victims of German Fascism. Take Charles Bennett, one of Hitchcock’s chief writers at Gaumont-British, who contributed to nearly every screenplay during the director’s 1930s period. Years later in the 1940s, Bennett worked with the British Ministry of Information to write pure propaganda films. Bennett had a close relationship with Hitchcock as a primary contributor to screen scenarios, along with the director’s often uncredited wife Alma Reville, and together their ideas were inspired by newspaper headlines, books, and plays. It was Bennett who suggested that Hitchcock adapt John Buchan’s 1915 novel The Thirty-Nine Steps, a First World War spy yarn whose title refers to the steps that lead to the secret headquarters of a German spy organization.

In Hitchcock’s 1935 film of The 39 Steps, the fast-paced scenario involves Canadian Richard Hannay, played by the popular and debonair Robert Donat, who evades British authorities and exposes an international conspiracy after being wrongly accused of murder—a common Hitchcock setup. Once again, the MacGuffin is conveyed in a dying breath. A murdered woman, a confessed spy who follows Hannay home from a London Music Hall, finds herself stabbed by foreign spies. In her last moments, she warns Hannay to locate a man about the mysterious “39 Steps” without explaining their significance. Throughout the story, the hero tries to evade authorities and uncover a foreign plot orchestrated by the outwardly reputable Professor Jordan (Godfrey Tearle)—all while being handcuffed to the reluctant Pamela (Madeleine Carroll), an early Hitchcock blonde, in a charming meet-cute. Hannay soon exposes the meaning of “The 39 Steps” by probing Mr. Memory (Wylie Watson), a Music Hall entertainer renowned for his ability to recollect any documented fact. When Hannay confronts him on the stage before a crowd of onlookers, Mr. Memory, a pawn of the conspirators, reveals, “The 39 Steps is an organization of spies, collecting information on behalf of the Foreign Office of—.” And before he can say “Germany,” the name Hitchcock intended to evoke, Mr. Memory is shot. The moment cleverly allows the viewer to complete Mr. Memory’s sentence, making an assumption based on the political situations of the day. Viewers got the message in both England and the United States, interpreting the spies as a “proto-Nazi” threat, according to Hitchcock scholar William Rothman.

As Hitchcock continued to be successful abroad and receive offers from Hollywood studios, his anti-fascist messages became more evident with each new film. Secret Agent (1936) may take place during the First World War, but its elaborate spy plots, double agents, and German schemes reminded audiences of just how Germany operated during wartime—their methods remained in the shadows, calculating, and deadly, according to the film. Similar themes dominate Sabotage (1936), based on Joseph Conrad’s 1907 novel The Secret Agent (no relation to the earlier 1936 Hitchcock film), which opens with a shot of the title’s dictionary definition: “Willful destruction of buildings or machinery with the object of alarming a group or persons or inspiring public uneasiness.” The story involves a movie theater owner, the German-accented Mr. Verloc (Oskar Homolka), who works with a group of German-accented spies to incite chaos in London. His wife (Sylvia Sidney) soon suspects his treachery and, after her teenage brother Stevie (Desmond Tester) dies in a bombing, she kills her husband. Although the precise political motivations remain vague, Hitchcock used the story to echo the paranoia running through Europe. It is interesting to note that Bennett, who wrote the screenplay for Sabotage, changed Verloc’s first name from Adolf, as Conrad’s novel named him, to Karl. Although Bennett and Hitchcock wanted to hint at the looming threat, they did not want to anger Germany into an undue conflict. Regardless, the implication of a German threat remains present if unspoken in the film.

In the United States, Sabotage played with a less politicized title, A Woman Alone, but revival houses also began to show Hitchcock’s related spy films as a promotional effort by Gaumont-British. Americans saw a pattern emerge when revival houses screened The Man Who Knew Too Much, The 39 Steps, and Secret Agent next to A Woman Alone. The anti-fascist messages were not Gaumont-British’s top priority, of course, but for the filmmakers overseas, they gave their work some relevance in the growing European war. After the release of A Woman Alone, both MGM and David O. Selznick’s company Selznick International courted Hitchcock for Hollywood. The director took advantage of his demand and visited the United States for an extended press and sightseeing tour in 1937. Charming members of the press in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington D.C. with his size, the director’s newfound exposure, combined with the recirculation of his 1930s spy films, helped turn Hitchcock into a household name.

In the United States, Sabotage played with a less politicized title, A Woman Alone, but revival houses also began to show Hitchcock’s related spy films as a promotional effort by Gaumont-British. Americans saw a pattern emerge when revival houses screened The Man Who Knew Too Much, The 39 Steps, and Secret Agent next to A Woman Alone. The anti-fascist messages were not Gaumont-British’s top priority, of course, but for the filmmakers overseas, they gave their work some relevance in the growing European war. After the release of A Woman Alone, both MGM and David O. Selznick’s company Selznick International courted Hitchcock for Hollywood. The director took advantage of his demand and visited the United States for an extended press and sightseeing tour in 1937. Charming members of the press in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington D.C. with his size, the director’s newfound exposure, combined with the recirculation of his 1930s spy films, helped turn Hitchcock into a household name.

In the Senate, meanwhile, North Dakota’s isolationist Senator Gerald P. Nye and his “Nye Committee” launched the so-called “merchant of death” hearings in the Senate in 1934, arguing that “munitions makers had made enormous profits during the war” and resorted to bribery of government officials to secure the United States’ entrance into the First World War. After 93 hearings from 1934 to 1936, the Nye Committee’s findings were nonetheless inconclusive in trying to connect “selfishly interested organizations” with charging the United States into the war. The outcome of the hearings, however, was an escalating suspicion among Americans now convinced that their country should not become involved in a foreign conflict. Nye warned about the British film industry’s ability to convince American citizens to enter the First World War, and he worried still about their influence during the current European conflict.

Hitchcock’s final film for Gaumont-British was The Lady Vanishes (1938), and it makes the most overt case against German aggressions of any of his British spy-thrillers. Often cited as Hitchcock’s favorite of his own British productions, the film was based on Ethel Lina White’s 1936 novel The Wheel Spins. The story involves a young British socialite, Iris (Margaret Lockwood), who befriends elderly governess Miss Froy (Dame May Whitty) during a westward train voyage from the fictional Eastern European country of Bandrieka (“one of Europe’s few undiscovered corners”). When Miss Froy goes missing, Iris teams with helpful folk music scholar Gilbert (Michael Redgrave) to expose a kidnapping conspiracy meant to obtain top-secret information known only to Miss Froy, a British secret agent. The MacGuffin is a melody memorized by Miss Froy, coded for purposes unknown. And while the film targets Germans as the culprits, the real target is British complacency. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who served from May 1937 to May 1940, was determined to appease Hitler and Mussolini sooner than engage in another war. Hitchcock, fresh from his American tour and ready to leave England for Hollywood, was fed up, as The Lady Vanishes shows.

The film contains numerous criticisms of British foreign policy and allusions to German aggression throughout Europe. The conspiring villains are once again thin disguises for Germans. Paul Lukas, a Hungarian-born émigré, plays the seemingly helpful Dr. Hartz—the villain who orchestrates Miss Froy’s kidnapping. Dr. Hartz evokes a Nazi with his accent, eventual SS-inspired uniform, German automobiles, and the Lugers carried by his cohorts. But the portrait of British indifference toward what their characters call the “international situation” is scathing. One character describes British diplomacy with the saying, “Never climb a fence if you can sit on it.” Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne play Charters and Caldicott, a pair of cricket-obsessed Englishmen willing to suppress key information about Miss Froy’s kidnapping if it means their train arrives in time to catch a cricket match. Hitchcock suggests what happens to cowards with a lawyer character, played by Cecil Parker, who wants to avoid getting involved. The lawyer worries about damaging his reputation if the reasons for his trip to Bandrieka (an illicit love affair) are exposed. To hide this, the adulterous lawyer claims to be a pacifist and objects when the British decide to act against the attacking spies. “You idiots,” he cries, “you’re inviting death!” When the lawyer tries to surrender, white flag and all, the German spies shoot him down. As Hitchcock biographer Patrick McGilligan observed about The Lady Vanishes, “The message is clear: England is kidding itself to think it can appease Hitler.”

After completing his uninspired final film under his Gaumont-British contract (Jamaica Inn, 1939), Hitchcock finally signed a deal with David O. Selznick to work in Hollywood, though his new appointment brought the director’s loyalties into question. Under the Selznick contract, Hitchcock made the gothic romance Rebecca (1940), which earned two Academy Awards, including Best Picture. During this time, Hitchcock’s former producer Michael Balcon, having produced many of Hitchcock’s 1930s spy-thrillers, openly criticized the director for leaving England shorthanded in its national efforts just as the war was getting started. Hitchcock’s patriotism came into question. But Hitchcock was opposed to making grand patriotic gestures to appease the media; he preferred to do things his way, such as quietly donating money to wartime causes, as observed by McGilligan in his book Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Perhaps Balcon’s criticism is why, for his second release in the United States, the director agreed to be loaned out by Selznick to producer Walter Wagner at United Artists for Foreign Correspondent.

After completing his uninspired final film under his Gaumont-British contract (Jamaica Inn, 1939), Hitchcock finally signed a deal with David O. Selznick to work in Hollywood, though his new appointment brought the director’s loyalties into question. Under the Selznick contract, Hitchcock made the gothic romance Rebecca (1940), which earned two Academy Awards, including Best Picture. During this time, Hitchcock’s former producer Michael Balcon, having produced many of Hitchcock’s 1930s spy-thrillers, openly criticized the director for leaving England shorthanded in its national efforts just as the war was getting started. Hitchcock’s patriotism came into question. But Hitchcock was opposed to making grand patriotic gestures to appease the media; he preferred to do things his way, such as quietly donating money to wartime causes, as observed by McGilligan in his book Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Perhaps Balcon’s criticism is why, for his second release in the United States, the director agreed to be loaned out by Selznick to producer Walter Wagner at United Artists for Foreign Correspondent.

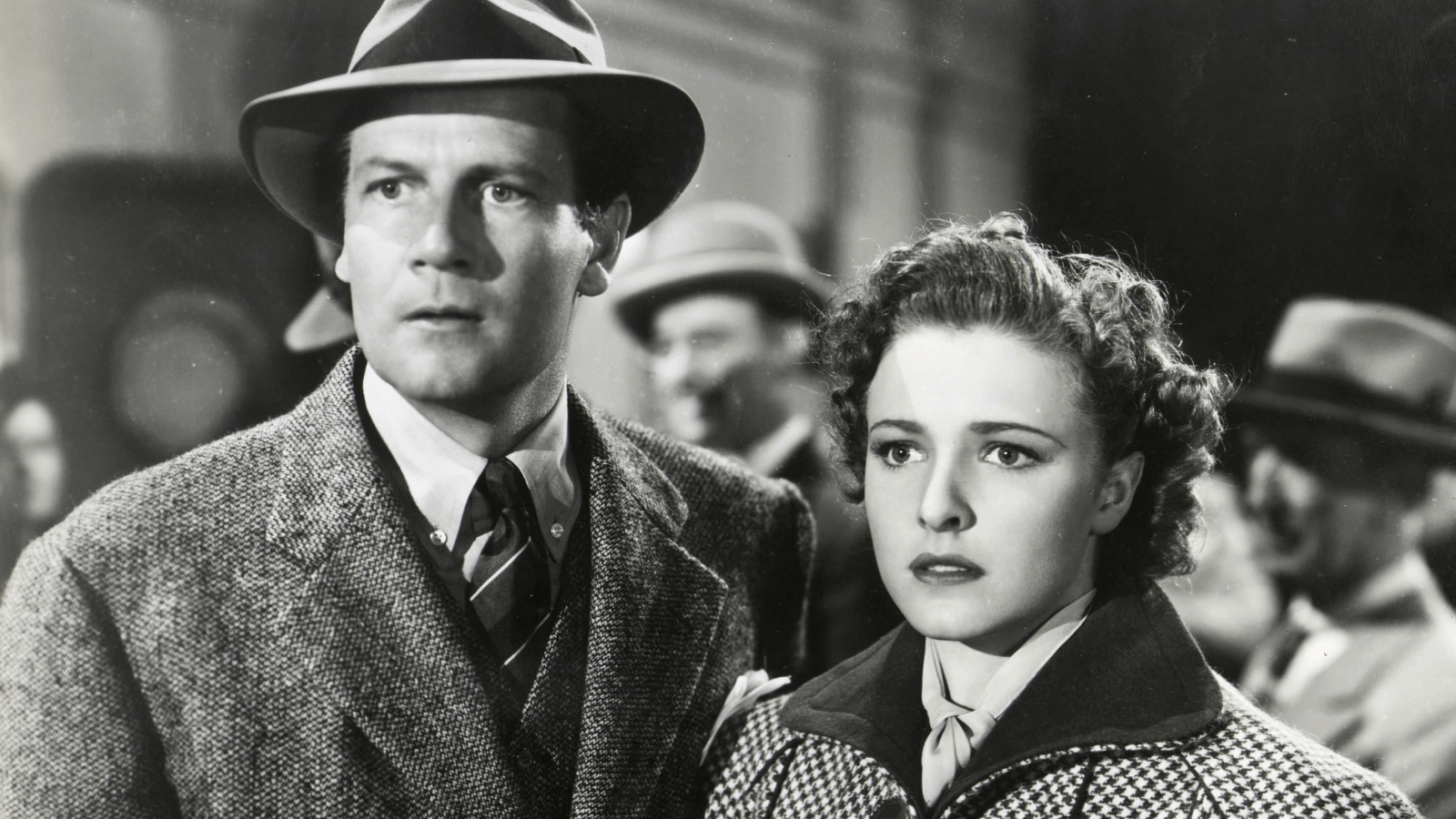

Hitchcock’s first spy-thriller in Hollywood and his most explicit anti-Nazi film during the pre-Pearl Harbor era, Foreign Correspondent resolves that only people of action will expose the motives of Nazi villains who work in the shadows and use reprehensible tactics. The story follows John Jones (Joel McCrea), a tough New York crime reporter enlisted to serve as a European correspondent to expose the “crime hatching on that bedeviled continent.” Renamed “Huntley Haverstock” by his editor Mr. Powers (Harry Davenport) for a more compelling byline, Jones knows nothing about the European conflict. But not long after arriving in England, he witnesses the assassination of Dr. Van Meer (Albert Basserman), a representative of the Universal Peace Party and author of an important peace treaty. With the help of fellow reporter Scott ffolliott (George Sanders), Jones learns Van Meer was not killed; it was a double. The Germans have kidnaped the real Van Meer for information about a secret clause in the treaty (the MacGuffin). Herbert Marshall plays Stephen Fisher, a foreign dignitary and a British citizen of German descent, whose daughter Carol (Loraine Day) represents Jones’ love interest. Although seemingly working alongside Jones, Fisher is an enemy agent that tries to have Jones killed, Jones and ffolliot outwit the enemy. Jones frees Van Meer from capture, finds Fisher on a plane to America, barely survives a plane crash when Germans shoot them down, and delivers the story to his editor. And despite the heroics and espionage thrills, Jones does not prevent the war—the film ends on September 3, 1939, the day the British and French declared war on Germany.

Foreign Correspondent was based on Personal History, journalist Vincent Sheean’s 1935 globe-trotting account of spies, revolution, and war that bears little resemblance to the film. Wagner purchased the film rights to Personal History in 1936, and the first adaptation featured a reporter witnessing fascism in the Spanish Civil War and learning about the anti-Semitic drives of Nazi Germany. The script served as a political indictment of Franco and Nazism, while also encouraging American patriotism to act. When Wagner submitted the screenplay to the PCA in 1938, Joseph Breen, head of the Production Code Administration’s enforcement division, warned against its explicit identification of Germans in the hope of preserving the German-speaking market. Breen also noted that the Personal History script contained messages designed to evoke “feelings against the present German regime, in the matter of its treatment of the Jews.” Breen and the Production Code sought to avoid contemporary politics in the movies, which would keep US politicians out of Hollywood and not upset the lucrative European markets. But between 1938 and 1940, several anti-Nazi films, including Warner Bros.’s Confessions of a Nazi Spy in 1939, had become more familiar among moviegoers in the United States. When Wagner submitted a revised script in 1940, written primarily by Charles Bennett, Breen was happy to report that the manuscript, now retitled Foreign Correspondent, had “little resemblance to the story we were concerned about two years ago.”

Bennett’s inclusion in the screenwriting process was central and influenced Foreign Correspondent’s anti-Nazi messages. In Hollywood, Bennett was active in anti-Nazi groups. Alongside director Victor Saville, he co-headed a secret group of British expatriates—including Boris Karloff, whose brother worked for MI6—operating in Hollywood to convince the United States to set aside its isolationist stance and support England. Bennett brought Hitchcock to the meetings and, along with collecting celebrity donations for charity projects designed to support the British, Hitchcock was compelled to participate in the cause. Whereas Hitchcock’s earlier British spy-thrillers can and were accused of too much subtlety by interventionists, Foreign Correspondent represents a stark movement from sneaky anti-Nazi implications to a more direct method of message-imbued filmmaking compared to other Hollywood spy films of the era. Bennett also infused ideas from his earlier adaptation of The 39 Steps for Hitchcock, including a similar MacGuffin locked in the mind of a single individual—Van Meer alone knows a clause of a treaty that could give the enemy an advantage in the impending war.

But the script Wagner submitted to Breen and the finished film remain quite different entities. After Bennett completed his foundational draft, Hitchcock followed his usual practice of hiring other writers to punch up the material, adding humor and idiosyncrasies. Joan Harrison, James Hilton, and Robert Benchley each contributed drafts. The film is not only a superb Hitchcock spy-thriller but consistently funny as well, capturing the flavor of newspaper comedies like His Girl Friday (1940) in the initial scenes. A running gag about another correspondent, Stebbings (Robert Benchley), who has used his expense account to drink and host beautiful women, provides consistent laughs—as does the banter between Jones and ffolliot. McCrea’s penchant for rapid-fire dialogue and comic timing lends the material an almost screwball tempo, a talent he would put to use for Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and The Palm Beach Story (1942) over the next two years. Indeed, Foreign Correspondent plays like a romantic comedy at times, complete with hilarious scenes involving a Latvian dignitary (Edward Conrad) whose knowing glances at the chemistry between Jones and Carol give the screenplay an almost Lubitschian touch.

But the script Wagner submitted to Breen and the finished film remain quite different entities. After Bennett completed his foundational draft, Hitchcock followed his usual practice of hiring other writers to punch up the material, adding humor and idiosyncrasies. Joan Harrison, James Hilton, and Robert Benchley each contributed drafts. The film is not only a superb Hitchcock spy-thriller but consistently funny as well, capturing the flavor of newspaper comedies like His Girl Friday (1940) in the initial scenes. A running gag about another correspondent, Stebbings (Robert Benchley), who has used his expense account to drink and host beautiful women, provides consistent laughs—as does the banter between Jones and ffolliot. McCrea’s penchant for rapid-fire dialogue and comic timing lends the material an almost screwball tempo, a talent he would put to use for Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and The Palm Beach Story (1942) over the next two years. Indeed, Foreign Correspondent plays like a romantic comedy at times, complete with hilarious scenes involving a Latvian dignitary (Edward Conrad) whose knowing glances at the chemistry between Jones and Carol give the screenplay an almost Lubitschian touch.

Foreign Correspondent also boasts some of Hitchcock’s most memorable sequences and technical tricks, making for one set piece after another of formal virtuosity. In one shot, cinematographer Rudolph Maté’s camera passes from outside, through a window, to an interior, all in a single shot—a trick modern filmmakers such as Alfonso Cuarón have used CGI to create. Elsewhere, when Jones witnesses Van Meer’s double assassinated in front of him while outside in the rain at a Universal Peace Party conference in Amsterdam, the killer slips away into a crowd. The camera from above sees only a black ocean of umbrella tops, a shot Steven Spielberg would pay homage to in 2002’s Minority Report. Jones then leaps into a car after the assassin, prompting a high-speed chase onto the countryside. The killer escapes into one of many old windmills. Jones follows inside the elaborate set piece, filled with dust and spider webs, silently maneuvering on wooden stairs to avoid being spotted by the spies hatching plans nearby. It’s a breathless sequence that uses convincing set design to enhance the production and suspense. But the thrills don’t end there. Later, Fisher assigns Jones a bodyguard (Edmund Gwenn), though he, too, is an enemy agent who tries and fails to push Jones to his death—twice. Few films in all of Hitchcock’s body of work contain so many individual sequences that dazzle.

The film was not only thrilling but timely for viewers in 1940. Just after filming began, Wagner insisted upon constant rewrites to insert current events into the script as they occurred in the real world, using bits of dialogue or newspaper headlines about the latest cities to fall to Nazi Germany. The new writers added the moment when Jones flees assassins by climbing outside on the balcony of the Hotel Europe; he grabs onto the hotel’s neon sign, causing a light to burst, leaving it to say “Hot Europe”—an image that implies the state of the European situation. During the wonderful plane crash sequence at the climax, a stuffy British woman objects to the situation, only to be silenced by German bullets. Not unlike the fate of the cowardly lawyer in The Lady Vanishes, Hitchcock demonstrates what happens to people who refused to get involved. The film also makes outright statements against the Nazis. Fisher remarks, “These people are criminal, more dangerous than your rumrunners and house-breakers. They’re fanatics. They combine a mad love of country with an equally mad indifference to life.” Yet, he aligns himself with them and, in the end, attempts to infiltrate the US by plane—a detail suggesting to viewers that Nazi agents may be on their way to the US, or already there.

Foreign Correspondent was all but completed and ready for release when Hitchcock traveled to England to deal with personal and business matters; however, the trip, where he saw the state of fear and chaos in his home country, convinced him to include a coda to the otherwise finished production. Hitchcock and Wagner hired writer Ben Hecht to author a final scene in which Jones, with Carol nestled by his side, delivers a radio broadcast into a microphone, warning the United States of the impending Nazi threat. The date of the broadcast—on September 3, 1939, the day England and France stood up and declared war—was a clear warning that war was imminent. And while the moment may seem ungainly attached after the fact to viewers today, Hitchcock’s spy-thriller story structure has an almost episodic use of set pieces and suspense setups that are loosely connected, carrying the viewer from one sequence to the next. The patchwork quality attributed to Hitchcock’s thrillers makes the final speech—capped with “The Star-Spangled Banner” playing over the end credits—feel natural and even stirring:

“The lights have gone out, so I’ll just have to talk off the cuff. All that noise you hear isn’t static; it’s death, coming to London. Yes, they’re coming here now. You can hear the bombs falling on the streets and the homes. Don’t tune me out, hang on a while. This is a big story. And you’re part of it. It’s too late to do anything here now except stand in the dark and let them come, as if the lights were all out everywhere, except in America. Keep those lights burning. Cover them with steel. Ring them with guns. Build a canopy of battleships and bombing planes around them. Hello, America, hang on to your lights: they’re the only lights left in the world!”

If the political and patriotic ambitions of Foreign Correspondent were at all in question, also consider John Jones’ name. John Jones derives from Little Johnny Jones, the 1907 stage musical by George M. Cohan featuring the song “Yankee Doodle Boy”—in fact, Johnny Jones is the Yankee Doodle Boy, making the film’s character a blatant stand-in for every patriotic American. Moreover, despite Breen’s earlier warnings, the film also names both Hitler and Nazis as the aggressors in Europe. (When Jones first receives his new post instructions from his editor, he asks whether talking to Hitler would be a good idea, “He must have something on his mind.”) Foreign Correspondent also turns the insinuations of Hitchcock’s earlier British spy-thrillers into statements. The unnamed spy consortium in The 39 Steps operates under the command of a seemingly respectable British citizen working for a foreign power; similarly, Mr. Fisher in Foreign Correspondent schemes with his German conspirators. What the German accents only imply in Hitchcock’s earlier spy-thrillers becomes apparent in Foreign Correspondent in the first scenes, when Jones’ editor gripes about his reporters’ inability to find out about what’s happening in Europe with Nazi Germany. Additionally, the film’s plane crash sequence sets off when a German destroyer fires on a passenger plane going from London to the United States.

With Foreign Correspondent, Hitchcock made a statement demonstrating how he had been editorializing against the Nazis since 1934. Not long after the release of the film in England, Balcon, who before had criticized Hitchcock for not being open in his contributions to the war effort, said he “regretted” his remarks given the new evidence of Hitchcock’s patriotism. In 1941, Hitchcock contributed more directly to his patriotic duty for England when he made two short propaganda films for the British Ministry of Information, “Aventure malgache” and “Bon Voyage,” as well as a feature-length 1945 documentary showing the grim results of the Holocaust, called Memory of the Camps (the film was not shown publicly until 2014 due to its unflinching images of mass death). Given these later developments, it’s easy to reconsider Hitchcock as a political and anti-Nazi filmmaker, not only in his post-1941 propaganda films but throughout his mid-to-late 1930s spy-thrillers. Like many of his contemporaries, Hitchcock played a delicate game of avoiding overt commentary and hiding his perspective behind allusion, accents, and visual signifiers before war was declared by England and France.

Due to the popularity of Hitchcock’s spy-thrillers in both England and the United States during this period, several copycats emerged, none more explicit in its anti-Nazi messages than Carol Reed’s Night Train to Munich—an essential anti-Nazi film from 1940. Often compared to Hitchcock, Reed was a skilled filmmaker contracted with Twentieth Century-Fox’s British division and emerged as a major director in England. After declaring war, the British film industry was more willing to call out the Nazis by name; meaning, any British imports would reach American audiences with a political openness not shared by many Hollywood productions. Although US distributors changed the title to Night Train, the omission of “to Munich” could not disguise the content. The film opens with a sequence of an impudent Adolf Hitler stomping his fist on maps of the countries he wants to invade (Austria, Sudetenland, Czechoslovakia), intercut with actual newsreel footage of Nazis marching through these countries. The story takes place just before England declares war, and its climactic sequence involving a cable car escape in the Swiss Alps takes place on September 3, 1939.

Loosely based on a magazine series penned by Gordon Wellesley, Night Train to Munich uses several Hitchcockian tropes. Much like Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes, the film stars Margaret Lockwood, contains an extended train sequence, and includes a MacGuffin locked in the mind of a genial senior citizen. Here, Lockwood is Anna Bomasch, a Czech woman thrown in a concentration camp because her father (James Harcourt) holds a secret formula (the MacGuffin) for improved armor plating on tanks. The scenario finds Anna teaming with a British spy, Gus Bennett (Rex Harrison), to carry out a daring escape by train from Berlin to Munich, and then to Switzerland. Night Train to Munich was such an homage to Hitchcock’s style that Reed brought back the two characters from The Lady Vanishes, the cricket-obsessed Charters and Caldicott, whose characteristic British stuffiness was a comic hit with audiences. But in Reed’s film, Charters and Caldicott take action to help the mission in the second half, punching out German officers, stealing their uniforms, and participating in the bold escape to Switzerland.

Because of its close relation to The Lady Vanishes, Night Train to Munich forces the viewer to reconsider Hitchcock’s spy-thrillers from 1934-1940, which helps bring out what at first may seem subtle about Hitchcock’s anti-Nazi messages. Everything that was subtextual or implied about Hitchcock’s anti-Nazi message resides on the surface in Reed’s film, but the message is ostensibly the same: Nazi Germany represents a threat to England and the entire world. Furthermore, the film pokes fun at Nazism, avoiding the grimmer realities of concentration camps and anti-Semitism in favor of jokes designed to make the Nazis look absurd. The script by Sydney Gilliat and Frank Launder includes several comic jabs at the reported bureaucracy of Nazi Germany, German monocles, the hypocrisy of Nazi ideology, and Hitler himself. One of the best jokes involves Charters’ inability to get through Mein Kampf. “I understand they give a copy to all the bridal couples over here,” Charters says. Caldicott replies, “Well I don’t think it’s that sort of book, old man.” The connections between Hitchcock’s spy-thrillers and the more apparent tactics used by Reed demonstrate that, though perhaps they were not mentioned by name, the Nazis had been present and criticized in British cinema through Hitchcock since 1934.

Of course, Hitchcock’s spy-thrillers released before the Americans decided to act, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, mark just a few examples of films that portrayed Europe’s conflict with Nazi Germany or depicted Nazis as a threat. Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), Fritz Lang’s Man Hunt (1940), and many others spoke out against Nazism. They were not motivated by a governmental agenda but by a humanitarian desire to combat hatred and intolerance. For many in Hollywood, it was important for the British to know Americans did not overlook their situation. The British nation was, after all, a major contributor of actors and directors in Hollywood, including Charles Laughton, Ray Milland, Laurence Olivier, Basil Rathbone, and others. The resulting films were designed to show that the British were dealing with clandestine Nazi maneuvers and increasing dangers. Hollywood studios attempted to portray the situation in Europe to convince viewers in the United States to rethink their isolationist stance. Popular and accessible films like Hitchcock’s saturated the American consciousness with similar themes. And while many of these anti-Nazi films read like state-sanctioned messages today, Hitchcock speaks from the heart and never sacrifices thrills or spectacle for the political message.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on March 3, 2022.)

Bibliography:

Barker, Jennifer Lynde. The Aesthetics of Antifascist Film: Radical Projection. Routledge, 2013.

Birdwell, Michael E. Celluloid Soldiers: Warner Bros.’s Campaign Against Nazism. New York University Press, 1999.

Bordwell, David, et al. The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Columbia University Press, 1985.

—. Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Brewer, Susan A. To Win the Peace: British Propaganda in World War II. Cornell University Press, 1997.

Ceplair, Larry, and Steven Englund. The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-60. University of Illinois Press, 1976.

Chadwin, Mark Lincoln. The Warhawks: American Interventionists before Pearl Harbor. Norton, 1970.

Cull, Nicholas J. Selling War: The British Propaganda Campaign against American “Neutrality” in World War II. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Dick, Bernard F. The Star-Spangled Screen: The American World War II Film. The University Press of Kentucky, 1985.

Doherty, Thomas. Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939. Columbia University Press, 2013.

Glancy, H. Mark. “Hollywood and Britain: MGM and the British ‘Quota’ Legislation.” The Unknown 1930s: An Alternative History of the British Cinema, 1929- 1939. Edited by Jeffrey Richards. I.B. Tauris, 1998, pp. 57-74.

Gottlieb, Sidney, editor. Hitchcock on Hitchcock: Selected Writings and Interviews. University of California Press, 1995.

Herman, Felicia. “Hollywood, Nazism, and the Jews, 1933-1941.” American Jewish History, no. 1, 2001, pp. 61-89.

Jewell, Richard B. The Golden Age of Cinema: Hollywood 1925-1945. Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Koppes, Clayton R. and Gregory D. Black. Hollywood Goes to War: How Politics, Profits and Propaganda Shaped World War II Movies. University of California Press, 1987.

McGilligan, Patrick. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Regan Books, 2003.

McLaughlin, Robert L. and Sally E. Parry. We’ll Always Have the Movies: American Cinema During World War II. The University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Powaski, Ronald E. Toward an Entangling Alliance: American Isolationism, Internationalism, and Europe, 1901-1950. Greenwood Press, 1991.

Rothman, William. Hitchcock: The Murderous Gaze. Second ed. SUNY Press, 2012.

Truffaut, François. Hitchcock. With the collaboration of Helen G Scott. Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Urwand, Ben. The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler. Yale University Press, 2013.

(Note: The above was excerpted and re-edited from a Master’s thesis, An Undeclared War: Hollywood’s Pre-Pearl Harbor Anti-Nazi Cinema.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review