The Definitives

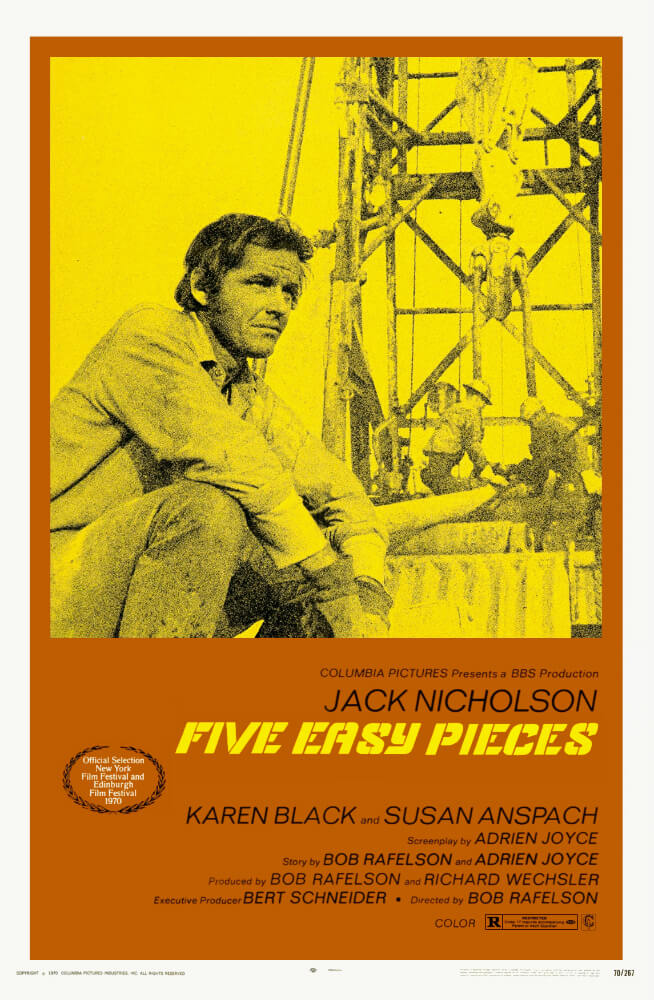

Five Easy Pieces (1970)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

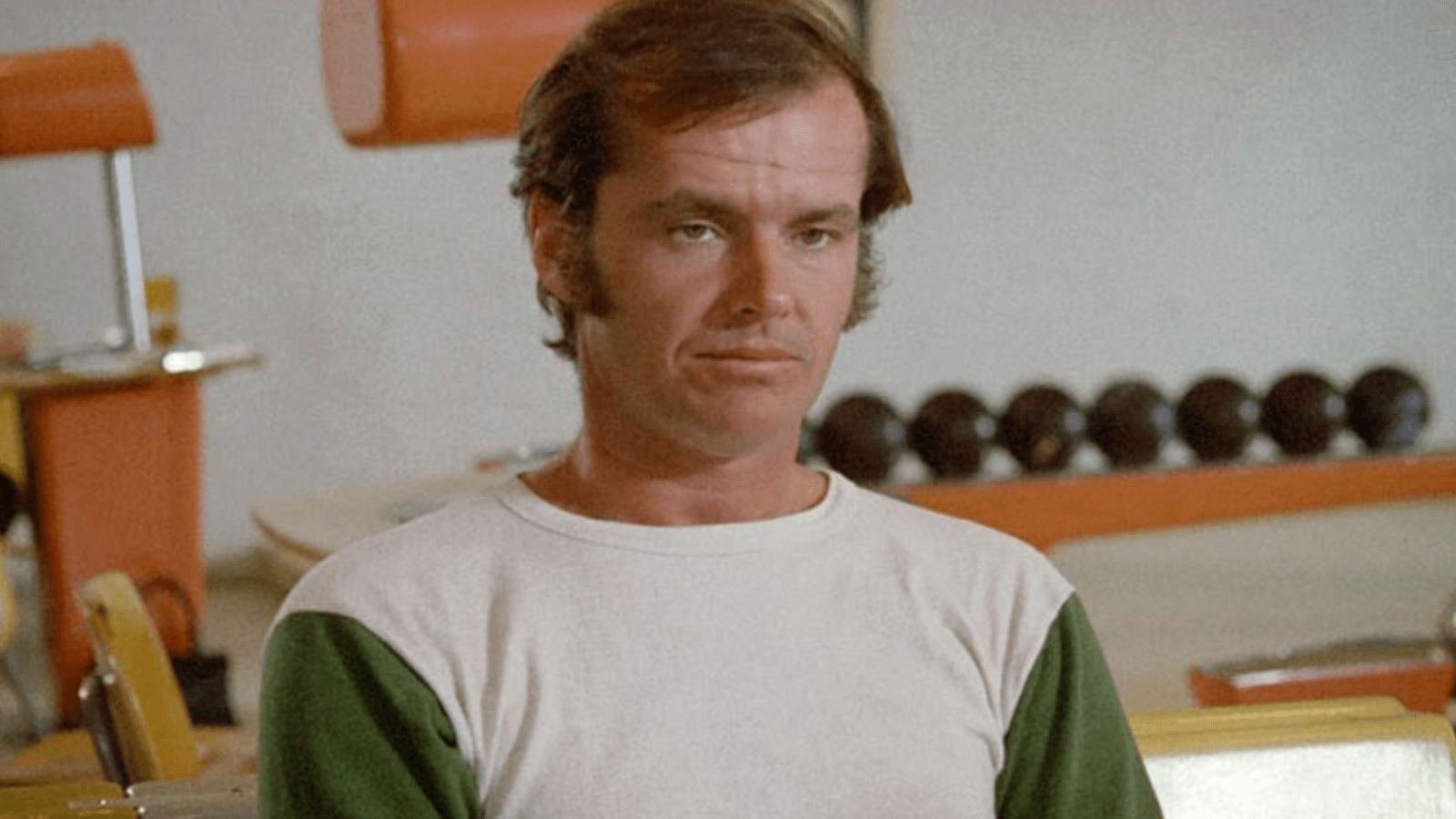

Somewhere between Hollywood and European arthouse cinema, between the twangy sounds of Tammy Wynette and the delicate piano of Fredrick Chopin, between blue-collar drudgery and upper-class conceit resides Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces, a landmark of counterculture filmmaking. It follows Jack Nicholson’s introspective Robert Eroica Dupea, who struggles to manage his shattered identity, suffocating as he tries to conform to prescribed worlds of class and social expectation. Released by BBS Productions in 1970, the film embraces a classical American myth in which a journey on the open road leads to answers. Gorgeously shot with cinematographer László Kovács’ eye for texture and space, its images find Bobby, as he is known, isolated within an expansive landscape. He may search for meaning and rebel against every system that presents itself, but he remains unable to feel settled or reveal his true self to anyone. He’s capable of profound emotion, “but it was all blocked up,” explains Rafelson. Throughout the film, Bobby finds rare moments of expression, usually coupled with solitude, yet they prove meaningless in his grand search. Alienated, adrift, and fearful that he will never be settled, Bobby is an icon of a rare brand of cinema that recognizes the need for freedom and rebellion, even while it acknowledges that such ideas are cinematic fantasies. The film’s reality is far more stifling, bleak, and equivocal.

Five Easy Pieces typifies the so-called Hollywood Renaissance, a transitional period in which auteurs inspired by European arthouse filmmakers flourished in America for a few short years from roughly 1968 to the late 1970s. This period of change in Hollywood created a disruption in traditional filmmaking rivaled only by the advent of sound. Most studios before this era experienced a recession and feared financial ruin. Television had taken over a major chunk of the audience, and theatrical attendance reached all-time lows. The studios responded by manufacturing mostly hollow larger-than-life productions and gimmicks to get people into theaters. Some of them, such as Fox’s The Sound of Music (1965), attracted viewers. Many more, such as Fox’s Doctor Dolittle (1967), produced losses in the millions. The culture had changed along with the tumultuous 1960s that overflowed with assassinations, the Civil Rights movement, the sexual revolution, antiwar fervor, Timothy Leary’s opening of minds with LSD, the Watergate scandal, and the resignation of Richard Nixon. In the wake of all this, a liberal counterculture stopped going to Hollywood’s traditionalist products. Instead, they wanted films that reflected how they felt, which looked like recent imports from Ingmar Bergman, Michelangelo Antonioni, and François Truffaut, which played at arthouses, college campuses, and, in a savvy move by Roger Corman, drive-in theaters. American filmmakers responded with films rooted in European aesthetics, offering a level of self-examination and social criticism rare for America. For a time, it was exactly what audiences wanted.

Amid so much disillusion and change, BBS Productions captured the youth and counterculture spirit more than any other production company at the time. In their brief run between 1968 and 1972, they launched an active rebellion against Hollywood archetypes. Its founders, Rafelson and Bert Schneider, first collaborated on the hit television show The Monkees, inspired by Beatlemania and Richard Lester’s film A Hard Day’s Night (1964). The TV series ran for two years, manufactured a chart-topping band, and inspired Rafelson’s feature debut starring The Monkees, the psychedelic bomb Head (1968). Under Rafelson and Schneider’s Raybert Productions (Rafelson + Bert = Raybert) banner, they released the breakthrough Easy Rider (1969), directed by and starring Dennis Hopper, which earned over $19 million on an investment of $375,000, giving them leverage to negotiate a deal with Columbia Pictures to finance and distribute original films. As long as budgets remained under $1 million, their company could maintain creative control. Along with producer Steve Blauner, Raybert became BBS, styled after the first letter in the principals’ first names. BBS released just a handful of films, starting with Five Easy Pieces, whose success and awards recognition established their artistic ambition with new talents and unconventional methods.

Amid so much disillusion and change, BBS Productions captured the youth and counterculture spirit more than any other production company at the time. In their brief run between 1968 and 1972, they launched an active rebellion against Hollywood archetypes. Its founders, Rafelson and Bert Schneider, first collaborated on the hit television show The Monkees, inspired by Beatlemania and Richard Lester’s film A Hard Day’s Night (1964). The TV series ran for two years, manufactured a chart-topping band, and inspired Rafelson’s feature debut starring The Monkees, the psychedelic bomb Head (1968). Under Rafelson and Schneider’s Raybert Productions (Rafelson + Bert = Raybert) banner, they released the breakthrough Easy Rider (1969), directed by and starring Dennis Hopper, which earned over $19 million on an investment of $375,000, giving them leverage to negotiate a deal with Columbia Pictures to finance and distribute original films. As long as budgets remained under $1 million, their company could maintain creative control. Along with producer Steve Blauner, Raybert became BBS, styled after the first letter in the principals’ first names. BBS released just a handful of films, starting with Five Easy Pieces, whose success and awards recognition established their artistic ambition with new talents and unconventional methods.

Nicholson, co-writer of Head and creative force behind several other BBS productions, called the company “The freest possible film situation.” They committed themselves to experimentation, free from the carefully demarcated limits of Hollywood filmmaking; free to embrace the wanderlust of Jack Kerouac; free to depict complicated sexual relationships; free to mourn the country’s former glory and lament its downswing; free to express their existential disenchantment. In his book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind wrote, “BBS quickly became a hangout for a ragtag band of filmmakers and radicals of various stripes. There was no hipper place in Hollywood.” Over the next few years, BBS would release Peter Bogdonovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971), Henry Jaglom’s A Safe Place (1971), Nicholson’s directorial debut Drive, He Said (1972), and Rafelson’s second (and final) film for BBS, The King of Marvin Gardens (1972)—whose failure at the box-office prompted Columbia to cancel their deal, thus ending BBS’s run. Even so, their brief string of films introduced European art cinema characteristics—cerebral, aesthetically complex, inscrutable characters, auteur-driven—into the traditional motifs of American genre and narrative linearity. BBS created an interest in filmmakers who differentiated themselves from what domestically had become familiar, tired, traditionalist, and worst of all, safe.

Their greatest film is Five Easy Pieces. It opens with Tammy Wynette’s “Stand By Your Man” on the soundtrack and Nicholson’s Bobby Dupea earning a living as a California oil worker. Its deceptive first scenes create assumptions about the character and the film he inhabits. After work, he returns home to his girlfriend, Rayette (Karen Black), and they prepare for a night of bowling with their trailer park friends, Elton (Billy Green Bush) and Stoney (Fannie Flagg). Gradually, the film reveals Bobby’s perpetually dissatisfied state. Once a talented pianist from a well-off family of musicians, Bobby is a willful social outcast hiding in a blue-collar disguise. When Bobby learns from his sister Partita (Lois Smith) that their father (William Challee) is dying, he resolves to head north to Puget Sound to see him. Begrudgingly, he brings Rayette along for the ride—a classical journey of the rootless American on a mythical quest for self-discovery. There, he hides Rayette in a hotel and reconnects with his family, including his eccentric brother (Ralph Waite), and his brother’s fiancée Catherine (Susan Anspach), the latest in another of Bobby’s many aimless sexual conquests. But there’s no hope of familial reconciliation nor even a future with the pregnant Rayette, not for the discontented Bobby, who resolves to flee northward in the final scene.

The first BBS production, Five Easy Pieces came on the heels of Easy Rider, which had put Nicholson’s services into high demand. Although the actor had been around for several years working for Roger Corman and Monte Hellman on low-budget schlock and genre pictures, his standout supporting role in Hopper’s film catapulted him into stardom. Mike Nichols snagged him for Carnal Knowledge (1971), but not before Rafelson convinced the actor to appear in Five Easy Pieces. The screenplay came from Carole Eastman, who, credited as Adrien Joyce, started as an actress before writing The Shooting for Nicholson and Hellman in 1967. In 1969, she worked with French auteur Jacques Demy on his English-language debut Model Shop, and after Five Easy Pieces, she would collaborate with Nicholson twice more. Working closely with Rafelson on the story, they planned out the film’s broad strokes from Rafelson’s own experiences, coming from a privileged Jewish family in New York City to becoming a rebellious adventurer. Rafelson had only two demands: Eastman should make Bobby a former pianist and give the script “a moment where he’s playing the piano with his hair blowing in the breeze, like Cornel Wilde in A Song to Remember.” Eastman accommodated the request, capturing a man eternally at odds with himself. Film critic Colin Gardner called Eastman’s creation a “musical prodigy turned prodigal son” who finds himself in a series of unsatisfying relationships. The title, referring to a beginner’s guide to piano, features a subtextual meaning as Bobby finds himself in a series of intentionally uncomplicated relationships. For someone who can play Chopin, playing “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” might prove insultingly simple.

The first BBS production, Five Easy Pieces came on the heels of Easy Rider, which had put Nicholson’s services into high demand. Although the actor had been around for several years working for Roger Corman and Monte Hellman on low-budget schlock and genre pictures, his standout supporting role in Hopper’s film catapulted him into stardom. Mike Nichols snagged him for Carnal Knowledge (1971), but not before Rafelson convinced the actor to appear in Five Easy Pieces. The screenplay came from Carole Eastman, who, credited as Adrien Joyce, started as an actress before writing The Shooting for Nicholson and Hellman in 1967. In 1969, she worked with French auteur Jacques Demy on his English-language debut Model Shop, and after Five Easy Pieces, she would collaborate with Nicholson twice more. Working closely with Rafelson on the story, they planned out the film’s broad strokes from Rafelson’s own experiences, coming from a privileged Jewish family in New York City to becoming a rebellious adventurer. Rafelson had only two demands: Eastman should make Bobby a former pianist and give the script “a moment where he’s playing the piano with his hair blowing in the breeze, like Cornel Wilde in A Song to Remember.” Eastman accommodated the request, capturing a man eternally at odds with himself. Film critic Colin Gardner called Eastman’s creation a “musical prodigy turned prodigal son” who finds himself in a series of unsatisfying relationships. The title, referring to a beginner’s guide to piano, features a subtextual meaning as Bobby finds himself in a series of intentionally uncomplicated relationships. For someone who can play Chopin, playing “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” might prove insultingly simple.

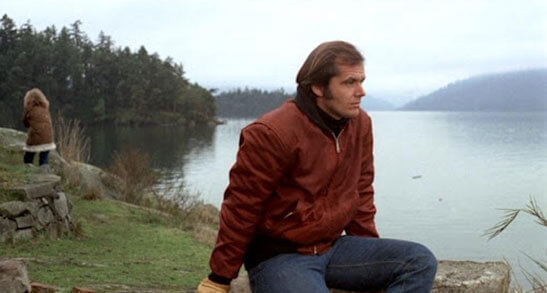

Rafelson shot on location and in sequence over six weeks in the fall of 1969, tracing the screen story from oil fields in Bakersfield, California, to the roads of Eugene, Oregon, to an island off the coast of Vancouver (standing in for Puget Sound). The efficient yet meticulous director obsessed over small details, including the particular sound of a rattling ashtray in Bobby’s car when he picks up two hitchhikers. Nicholson biographer Dennis McDougal wrote that Rafelson tried “fifty different car ashtrays” to get the right sound before he would shoot the scene. Rafelson wavered about his film’s ending, too. Eastman’s original ending echoed the Chappaquiddick incident of 1969, leaving Bobby and Rayette to meet their demise when they drive off a bridge into a river. Bobby drowns, and Rayette swims to shore and finds him dead. Rafelson wanted something more open-ended, like Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp walking into the distance with nothing to his name but the clothes on his back. Bobby resolves to hitch a ride with a trucker heading north. He abandons not only Rayette but his car and belongings at a filling station. This perfectly ambiguous conclusion nods to Rafelson’s Antonioni-esque use of space that reflects Bobby’s psychological hangups inside vast, empty landscapes, where oil rigs chug away, or the Pacific Northwest panorama overwhelms. The style creates a contrast of natural serenity invaded by nagging, penetrative movement, or worse, a serenity with which Bobby remains at odds.

Bobby Eroica Dupea remains one of the most complex and unsolvable screen characters. Any Screenwriting 101 textbook tells us that a protagonist must have goals, wants, and desires, and we must understand the reasons behind their yearning. Bobby does not know what he wants. However, his inscrutability is necessary since he actively refuses to be understood. Critic Kent Jones associates his malaise with sixties discontents: “They were discontented with the choices offered to them. They were acutely aware of their discontent, and they were trying to find a way to act on that awareness.” Sure enough, Bobby acts by running away from his failures, shacking up with easy women, and subsisting on the margins. Lost in a lonely existence, seemingly without purpose, Bobby’s dilemma situates Five Easy Pieces into a type of art cinema that took a cue from European antecedents. Scholar Thomas Elsaesser categorizes the film as “liberal” cinema that combines “the unmotivated hero” with a journey, in this case, the classical American road movie section in the middle where Bobby and Rayette travel from California to Washington toward his self-discovery. Elsaesser writes that travel affects the narrative form and how the audience views such characters, but it also encapsulates “the fading confidence in being able to tell a story.” Although Elsaesser criticizes the use of a journey to appease the traditional cinematic demand for movement as a replacement for existential movement, Rafelson embraces moments of stillness that almost luxuriate in Bobby’s condition at his most introspective. Keeping the camera with Bobby, both in moments of silence and solitude or mobility, creates a desire in the audience to know Bobby, even if it’s unclear what he wants. It’s an alternative to the Screenwriting 101 rules that invest viewers in a driven character by asking us to decide what drives him.

If there’s any substantive clue about the root of Bobby’s unease, it comes from the one scene over which Nicholson and Rafelson butted heads during production—when Bobby opens up to his father, who has suffered two strokes and sits mute, paralyzed. Rafelson wanted Nicholson to cry for the scene. Nicholson refused. After hours of debate and the crew on the clock, Rafelson resorted to extreme measures. He sent everyone home except Nicholson and William Challee, bringing them both out to an isolated field. Rafelson alone shot the scene and held the boom mic. Still, Nicholson couldn’t get into the mood. “If I’m going to do it, I sure can’t do it with this dialogue,” he said. Nicholson, no slouch in the screenwriting department, crossed out the script’s lines and wrote his own on the spot: “I guess you’re wondering what happened to me after my auspicious beginnings,” Bobby tells his father, before breaking down completely. He confesses to moving around a lot, “not because I’m looking for anything really, but ’cause I’m getting away from things that get bad if I stay.” Alas, Bobby receives no sense of recognition or acknowledgment from his father; he can only offer an apology for not living up to his father’s expectations and hope that his message was received. The scene is all the more tragic because, given what transpires in the final shots, it’s apparent that Bobby does not earn the closure he sought from his divulgence.

If there’s any substantive clue about the root of Bobby’s unease, it comes from the one scene over which Nicholson and Rafelson butted heads during production—when Bobby opens up to his father, who has suffered two strokes and sits mute, paralyzed. Rafelson wanted Nicholson to cry for the scene. Nicholson refused. After hours of debate and the crew on the clock, Rafelson resorted to extreme measures. He sent everyone home except Nicholson and William Challee, bringing them both out to an isolated field. Rafelson alone shot the scene and held the boom mic. Still, Nicholson couldn’t get into the mood. “If I’m going to do it, I sure can’t do it with this dialogue,” he said. Nicholson, no slouch in the screenwriting department, crossed out the script’s lines and wrote his own on the spot: “I guess you’re wondering what happened to me after my auspicious beginnings,” Bobby tells his father, before breaking down completely. He confesses to moving around a lot, “not because I’m looking for anything really, but ’cause I’m getting away from things that get bad if I stay.” Alas, Bobby receives no sense of recognition or acknowledgment from his father; he can only offer an apology for not living up to his father’s expectations and hope that his message was received. The scene is all the more tragic because, given what transpires in the final shots, it’s apparent that Bobby does not earn the closure he sought from his divulgence.

The scene represents one of the only times audiences would see beyond what, in subsequent years, would become the iconic Jack Nicholson veneer—that devilish smile, those signature sunglasses, his arched eyebrows, his occasional public outbursts, and confident masculinity that includes a reputation as a notorious ladies man. This scene defies all of that when Bobby allows himself to open up to his father, but only in isolation, only when his father cannot respond. Nicholson disappears into the role. There isn’t a trace of the crafted persona known as “Jack” that would reside beneath most of his subsequent parts, and all of which seem to be a response to his larger-than-life celebrity that emerged from this role. Although Nicholson’s stardom began with Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces catapulted him into leading-man status. McDougal writes that the film solidified him as “the new American Antihero.” He constantly worked in the ensuing years, tallying up a record number of Oscar nominations and several wins in The Last Detail (1973), Chinatown (1974), One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Terms of Endearment (1983), and others. Writers at the time compared him to Marlon Brando or James Dean. But there was an unconventional appeal about Nicholson, making the closest comparison Humphrey Bogart—an actor who could play a romantic lead or a scabrous villain, but usually something in-between. As writer Robert Sellers observed, “One of the astonishing things about Jack’s career is how long he’s managed to be both a subversive and an institution.”

Five Easy Pieces received the best response of any BBS production, apart from maybe The Last Picture Show. After premiering at the New York Film Festival in 1970, the film earned rave reviews and four Oscar nominations (for Best Director, Best Actor, Best Screenplay, and Black for Best Supporting Actress). “Line for line, it contains the best dialog—accurate, revealing, funny—that I have listened to in a very long time,” wrote Charles Champlin in the L.A. Times. Many viewers clung to Bobby’s scathing insults, encapsulated by the memorable diner scene. The scene was inspired by an actual incident a decade earlier when, at Pupi’s on the Sunset Strip, Nicholson swept the table’s contents onto the floor during an argument. What was the original argument about? Supposedly, no one remembers. But Nicholson’s penchant for public tantrums would help establish his legacy over the years, following him into the 1990s when he smashed a man’s car with a golf club or shouted courtside at Lakers games. In any case, Bobby, who wants a side of plain toast, responds to the diner’s “no substitutions” rule devastatingly: “I’ll make it as easy for you as I can,” he tells the server. “I’d like an omelette, plain, and a chicken salad sandwich on wheat toast, no mayonnaise, no butter, no lettuce, and a cup of coffee […] Now all you have to do is hold the chicken, bring me the toast, give me a check for the chicken salad sandwich, and you haven’t broken any rules.” When he tests her patience by telling her where to put the chicken—“I want you to hold it between your knees”—she tells them to leave. That’s when Bobby sweeps the glasses and menus onto the floor. It’s one of those scenes that extends beyond its rather superfluous place in the context of the larger story, implanting itself into our “collective memory,” as Roger Ebert observed.

The film contains several moments of angry energy besides the diner scene: Bobby’s explosion in the car just before leaving for his childhood home after Rayette makes him feel guilty for leaving her behind. The tongue-in-cheek interlude when Bobby and Rayette pick up a couple of lesbians (Helena Kallianiotes, Toni Basil) who, enraged about “filth” and consumerism, prattle on endlessly, then, looking into the camera, one insists, “I don’t even want to talk about it.” Bobby’s wrestling match with his father’s nurse (John P. Ryan). The anger in these scenes accomplishes little. They’re nothing more than fruitless expressions of dissatisfaction—declarations and frustrated torrents about the state of the world. They also present a sharp contrast to the film’s morose tenor. But taking its cue from Bobby, Five Easy Pieces is a film of contradictions, signified by the protagonist’s shifting names and accents. Bobby and Robert, respectively, represent the oil worker and the pianist, clad in either hardhats and plaid flannel or turtleneck sweaters. In Bakersfield, Bobby speaks with a southern accent, bowls a good game, and enjoys drinking beer with his trailer park friend Elton. But Bobby is just the latest persona taken on by Robert, who has no southern accent and comes from an intellectual background. Bobby is a performance that hides Robert’s vulnerability, and the person Robert wants to be exists somewhere in-between the blue-collar worker and the stuffy intellectual, someone only Partita, who calls him both Bobby and Robert, can see.

The film contains several moments of angry energy besides the diner scene: Bobby’s explosion in the car just before leaving for his childhood home after Rayette makes him feel guilty for leaving her behind. The tongue-in-cheek interlude when Bobby and Rayette pick up a couple of lesbians (Helena Kallianiotes, Toni Basil) who, enraged about “filth” and consumerism, prattle on endlessly, then, looking into the camera, one insists, “I don’t even want to talk about it.” Bobby’s wrestling match with his father’s nurse (John P. Ryan). The anger in these scenes accomplishes little. They’re nothing more than fruitless expressions of dissatisfaction—declarations and frustrated torrents about the state of the world. They also present a sharp contrast to the film’s morose tenor. But taking its cue from Bobby, Five Easy Pieces is a film of contradictions, signified by the protagonist’s shifting names and accents. Bobby and Robert, respectively, represent the oil worker and the pianist, clad in either hardhats and plaid flannel or turtleneck sweaters. In Bakersfield, Bobby speaks with a southern accent, bowls a good game, and enjoys drinking beer with his trailer park friend Elton. But Bobby is just the latest persona taken on by Robert, who has no southern accent and comes from an intellectual background. Bobby is a performance that hides Robert’s vulnerability, and the person Robert wants to be exists somewhere in-between the blue-collar worker and the stuffy intellectual, someone only Partita, who calls him both Bobby and Robert, can see.

Trapped between these two poles, Bobby remains at odds with himself, and he chooses to break down the conceit and manners behind every social situation by inhabiting a rebellious alternative. His behavior is not involuntary but decidedly contrarian. After all, he could use his understanding of both sides to relate to them better, but instead, he feels driven to freedom on his own terms—a deeply romantic American ideal, albeit not without downfalls. Bobby is split between his two sides, and he regularly flees one only to find himself trapped in the other. In the film’s most lyrical scene, he escapes a traffic jam by getting out of his car, hopping onto the back of a truck that’s hauling furniture, and playing classical music on an upright piano. The truck scuttles across traffic onto a freeway exit, carrying Bobby away from his work-a-day life. Later, he walks out on his proper family dinner by getting soused at a local bar and then sleeps it off on a cold seaside dock. He volleys between his two identities, unable to find a suitable and true alternative and trapped inside the larger confining patterns of his life.

Moreover, the film does not condone his discontentment, in part because the sympathetic Rayette, in all her dim-witted and big-hearted innocence, remains on the receiving end. “I’m not a piece of crap,” she tells him, and later, “Why don’t you just be good to me for a change?” Bobby, insulting and unfaithful, uses women like Rayette—the most authentic person in the film next to Partita—because he finds them easy to manage. They allow him to flounder without demanding much. It’s a casual cruelty when he slips away from Rayette to pursue empty sex with a woman from the bowling alley (Sally Ann Struthers) or Catherine, with whom he sees some false premonition of a future. In the end, he knows he can’t be good to Rayette, or anyone, and their relationship might be one of the “things that get bad if I stay.” And while Five Easy Pieces ends with Bobby freeing himself from both Rayette and his family, suggesting a note of optimism, he adopts a southern accent again when he speaks to the trucker, signaling that he may be trying to escape into a familiar persona. In the truck’s cab in the last shots, he insists “I’m fine” over and over—the latest in a long line of self-delusions.

Hollywood films usually follow a prescribed formula, and if we equate such formulas to standard genres and archetypes, it’s impossible to set Five Easy Pieces, or any BBS production for that matter, into a traditional Hollywood formula. The same is true of Bobby and his ability to inhabit blue-collar and highbrow classes from within and without, which Rafelson uses to fashion a commentary on class—not by placing Bobby as a card-carrying member of both classes, but in contradictory relation to them. Bobby’s relationship with class is tantamount to the film’s place in Hollywood at the time. It is neither overly highbrow nor lowbrow escapism. Like Bobby’s knack for bowling and affinity for cheap beer, it features memorable scenes that appeal to the audience’s unpretentious, everyday frustrations. For instance, when Bobby loses his temper in the diner, one of the hitchhikers praises him for unleashing his anger and figuring out a way to get toast. But the film reminds us that Bobby’s cathartic behavior gets him nowhere when he reminds her, “Yeah, well, I didn’t get it, did I?” Most of the time, Hollywood operates in figures who represent clear definitional signs: the hero, the villain, the love interest, the confidant, the foil, etc. Their roles may have gradations or complications, but they require no stretch of the imagination to define. Alternatively, like Nicholson’s character, Rafelson’s film must be deciphered, figured out, and subjected to interpretation.

Hollywood films usually follow a prescribed formula, and if we equate such formulas to standard genres and archetypes, it’s impossible to set Five Easy Pieces, or any BBS production for that matter, into a traditional Hollywood formula. The same is true of Bobby and his ability to inhabit blue-collar and highbrow classes from within and without, which Rafelson uses to fashion a commentary on class—not by placing Bobby as a card-carrying member of both classes, but in contradictory relation to them. Bobby’s relationship with class is tantamount to the film’s place in Hollywood at the time. It is neither overly highbrow nor lowbrow escapism. Like Bobby’s knack for bowling and affinity for cheap beer, it features memorable scenes that appeal to the audience’s unpretentious, everyday frustrations. For instance, when Bobby loses his temper in the diner, one of the hitchhikers praises him for unleashing his anger and figuring out a way to get toast. But the film reminds us that Bobby’s cathartic behavior gets him nowhere when he reminds her, “Yeah, well, I didn’t get it, did I?” Most of the time, Hollywood operates in figures who represent clear definitional signs: the hero, the villain, the love interest, the confidant, the foil, etc. Their roles may have gradations or complications, but they require no stretch of the imagination to define. Alternatively, like Nicholson’s character, Rafelson’s film must be deciphered, figured out, and subjected to interpretation.

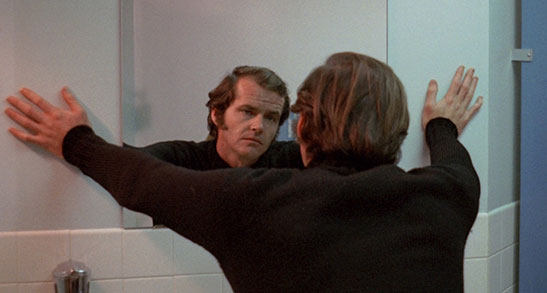

Although Five Easy Pieces’ relationship with the counterculture movement, and to some extent film history, might be typified by the iconic diner scene, its quieter moments resonate more. Consider when Bobby looks into the mirror and ponders leaving Rayette before he heads north to his family. Later, he repeats the action in the filling station restroom, searching for some existential resolution. When he leaves everything behind and boards the truck, the driver warns they’re going someplace “colder ‘n hell,” and this figure of speech captures the narrative disjunctions throughout Five Easy Pieces. Bobby either resigns himself to another kind of life, that of the blue-collar trucker, or plans to disappear northward. Neither option will fulfill him. Rather, Rafelson and Nicholson find the truest version of their character not in his memorable and quotable outbursts, nor the film’s ending, but in his occasional stillness and solitude. Watch the few seconds when his friends leave him to pay for beer at the bowling alley. He is alone. The commotion around him quiets. He loses himself in thought. This is the real Bobby Dupea, spied again later when Catherine leaves him by the beach, and he sits alone with no chance for a future with her. Caught between classes, identities, and even film style, Bobby, and by extension Five Easy Pieces, remains affecting because of its enduring, and devastating, discontentment.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks so much for your support, Mark!)

Bibliography:

Biskind, Peter. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. Simon and Schuster, 1998.

Campbell, Gregg M. “Beethoven, Chopin and Tammy Wynette: Heroines and Archetypes in ‘Five Easy Pieces.’” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 3, 1974, pp. 275–283. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43795659. Accessed 5 July 2021.

BBStory: An American Film Renaissance. Dir. Greg Carson. The Criterion Collection, 2009.

Cook, David. Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970-1979. University of California Press, 2002.

Ebert, Roger. “Five Easy Pieces.” RogerEbert.com, 16 March 20003. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-five-easy-pieces-1970. Accessed 5 July 2021/

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Notes on the Unmotivated Hero: the Pathos of Failure: American Films in the 70s,” Monogram, 1975, pp. 13-19.

Jones, Kent. “Five Easy Pieces: The Solitude.” Criterion.com, 25 November 2010. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1668-five-easy-pieces-the-solitude. Accessed 3 July 2021.

King, Noel. “Mersault Goes West: Five Easy Pieces and Art Cinema.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, no. 20, 1983, pp. 37–40. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44111896. Accessed 18 July 2021.

McDougal, Dennis. Five Easy Decades: How Jack Nicholson Became the Biggest Movie Star in Modern Times. Wiley; 1st edition, 2008.

Nystrom, Derek. “Hard Hats and Movie Brats: Auteurism and the Class Politics of the New Hollywood.” Cinema Journal, vol. 43, no. 3, 2004, pp. 18–41. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3661107. Accessed 5 July 2021.

Sellers, Robert. Hollywood Hellraisers: The Wild Lives and Fast Times of Marlon Brando, Dennis Hopper, Warren Beatty, and Jack Nicholson. Skyhorse, 2010.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review