The Definitives

Finding Nemo (2003)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

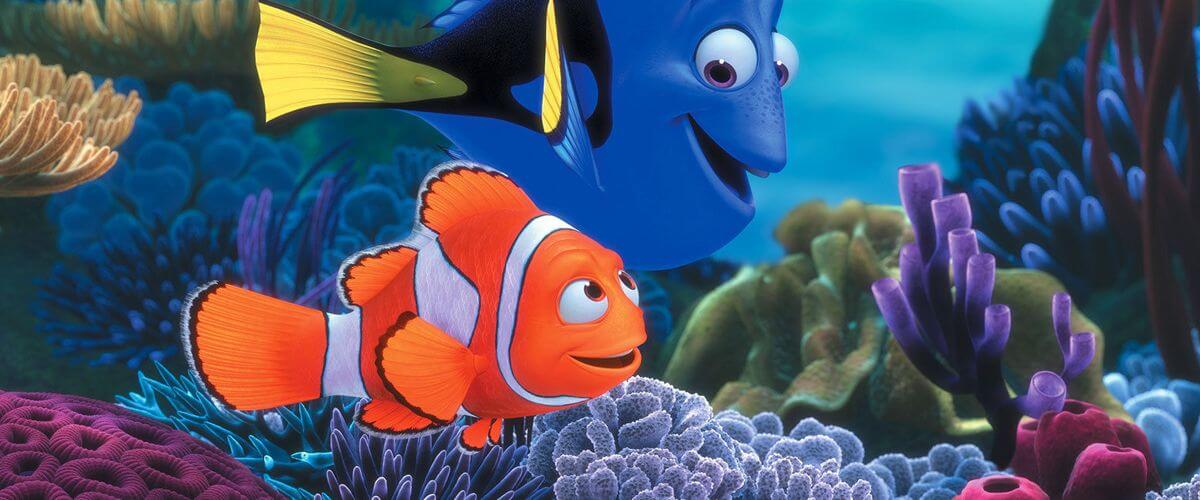

Finding Nemo contains an unlikely theme for an animated family film. Through the course of this gorgeously assembled adventure, the film’s audience experiences the natural world as a dangerous and unforgiving place just beyond the drop-off, fraught with death and countless hazards. However, the world is also beautiful and worth exploring, whether we do so through solidarity achieved alongside our loved ones, or brave Nature alone. Though the film ultimately delivers a warm message, the majority of this G-rated feature throws no end of peril at its characters, punishing their animated but no less lifelike bodies. Our clownfish hero Marlin searches for his lost son Nemo in the vast ocean from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef to Sydney, exposing himself to both literal and figurative shocks that make the viewer wince or tense in their seat. Marlin narrowly survives bloodthirsty sharks, a “swirling vortex of terror”, one underwater explosion, and several other dangers; at the same time, his son, imprisoned in a fish tank, subjects himself to certain death to get home. The danger is very real in Finding Nemo. And its threats might be too much for any viewer to process, especially children, if they were not counterbalanced by the film’s incredible sense that, not only are those we love worth risking life and limb for, but the beauty of the world itself is worth exploring no matter what obstacles there may be.

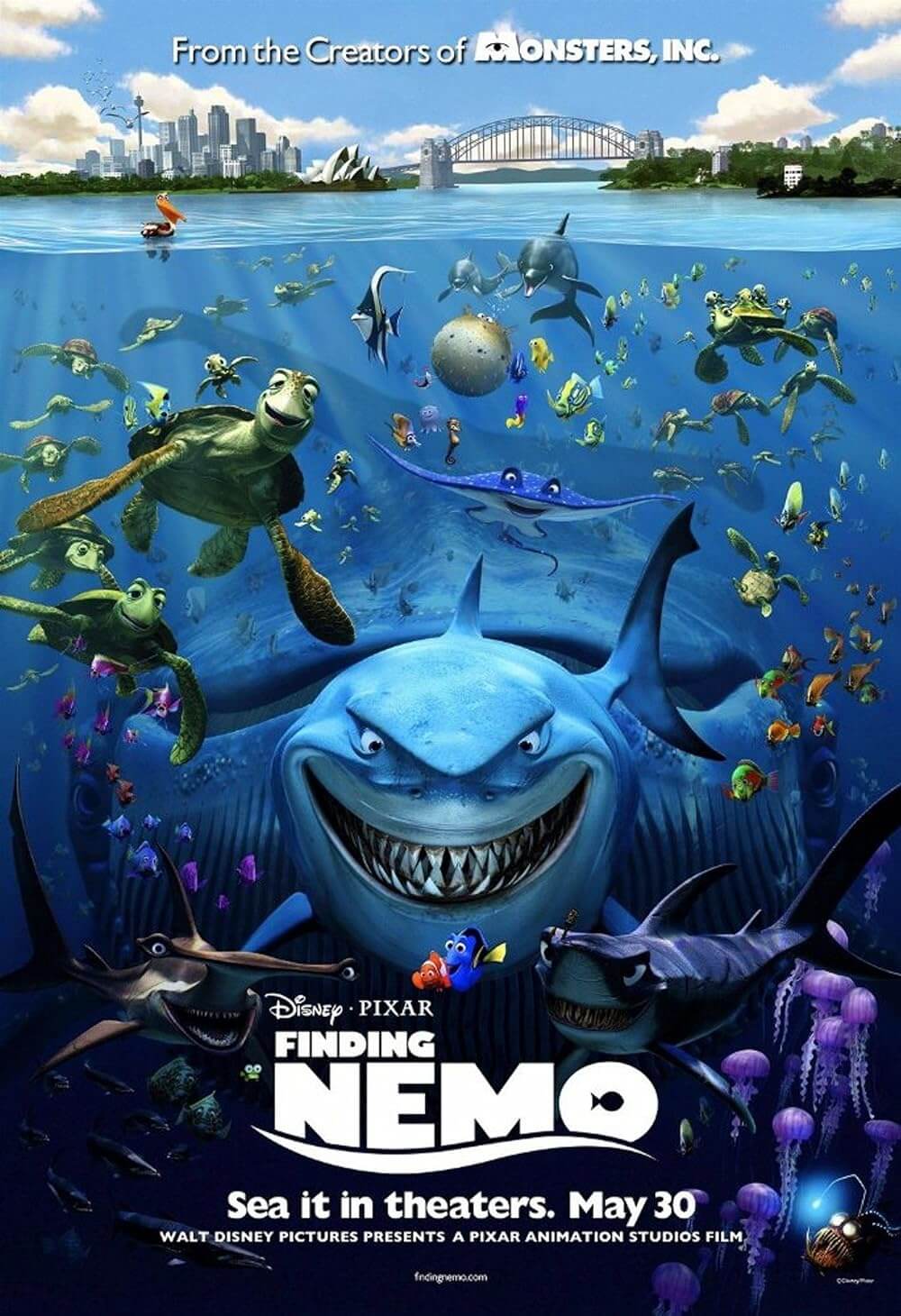

Pixar’s fifth animated feature debuted in 2003 to monumental successes, both commercial and artistic. After becoming the year’s second highest-grossing film with domestic receipts upwards of $380 million, and the highest-grossing animated film of all time at that point, Finding Nemo went on to earn three Academy Award nominations (Best Screenplay, Best Original Score, and Best Sound Editing) and won the Oscar for Best Animated Film. Indeed, critical and audience assessments demonstrated how the film enchanted with its splendid visuals and deceptively simple storytelling, as opposed to frightening us with its openness about the dangers of Nature. Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post summarized it well: “Finding Nemo will engross kids with its absorbing story, brightly drawn characters and lively action, and grown-ups will be equally entertained by the film’s subtle humor and the sophistication of its visuals.” Later, Finding Nemo would become one of the all-time best-selling releases on the DVD format—just another example of how fully the film would be ingrained into popular culture. Other animation studios were equally impressed. Aardman Animations’ 2006 release Flushed Away featured a random, sewer-bound goldfish that asked, “Have you seen my dad?” in a nod to Pixar’s film.

Finding Nemo elevates itself above previous Pixar releases—Toy Story (1995), A Bug’s Life (1998), Toy Story 2 (1999), Monsters, Inc. (2001)—through the splendor of its animated setpieces and the profound degree of emotional dimension that would come to define the studio. In many ways, watching this or any Pixar film requires a degree of effort otherwise nonexistent with other animation houses like DreamWorks, Fox, Illumination, or even Disney’s in-house efforts. So much visual information and soulful, resonant drama has been crammed inside each moment of every Pixar film, Finding Nemo above most, that the viewer never has a moment to shut off their brain—in the best way possible. Of course, this quality defines the very best of cinema, but Pixar was the first animation studio to establish themselves in Hollywood as animators that produced much more than cartoons for children—they produced art without demographics. Studio Ghibli’s Japanese master Hayao Miyazaki had been doing this for decades by 2003, but Miyazaki’s subtitled efforts failed to connect with the mainstream (sadly, only because his films are either subtitled or dubbed—an easy way of losing the interest of American audiences). And though Disney’s two-dimensional efforts had been the animation benchmark since the 1930s, many of their features could be described as kids’ stuff. Pixar was only just beginning to establish themselves as the premier animation studio, a title that would become and remain theirs after Finding Nemo, in particular after the on-again off-again retirement of Miyazaki.

Finding Nemo elevates itself above previous Pixar releases—Toy Story (1995), A Bug’s Life (1998), Toy Story 2 (1999), Monsters, Inc. (2001)—through the splendor of its animated setpieces and the profound degree of emotional dimension that would come to define the studio. In many ways, watching this or any Pixar film requires a degree of effort otherwise nonexistent with other animation houses like DreamWorks, Fox, Illumination, or even Disney’s in-house efforts. So much visual information and soulful, resonant drama has been crammed inside each moment of every Pixar film, Finding Nemo above most, that the viewer never has a moment to shut off their brain—in the best way possible. Of course, this quality defines the very best of cinema, but Pixar was the first animation studio to establish themselves in Hollywood as animators that produced much more than cartoons for children—they produced art without demographics. Studio Ghibli’s Japanese master Hayao Miyazaki had been doing this for decades by 2003, but Miyazaki’s subtitled efforts failed to connect with the mainstream (sadly, only because his films are either subtitled or dubbed—an easy way of losing the interest of American audiences). And though Disney’s two-dimensional efforts had been the animation benchmark since the 1930s, many of their features could be described as kids’ stuff. Pixar was only just beginning to establish themselves as the premier animation studio, a title that would become and remain theirs after Finding Nemo, in particular after the on-again off-again retirement of Miyazaki.

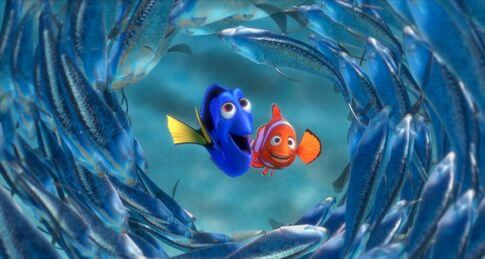

Pixar’s four earlier efforts each set the studio apart, but the universality of Finding Nemo connected with audiences even more than their earlier pictures. The story follows a not-so-funny father clown fish named Marlin (voiced by Albert Brooks). After losing his wife and most of her eggs in a barracuda attack, Marlin has become overprotective of his only remaining son, Nemo (Alexander Gould). Over-preparing for Nemo’s first day of school in their coral and anemone oasis, Marlin’s worst fears come true when Nemo is netted by a human scuba diver and taken further away than Marlin can imagine (if memory serves, to a dentist’s office located at P. Sherman, 42 Wallaby Way, Sydney, in Australia). Determined to get his child back, Marlin sets out on an episodic undersea odyssey, where he’s joined by an absent-minded blue tang fish named Dory (Ellen DeGeneres). Together, they encounter a group of bloodthirsty sharks who have tried to abstain from killing: “Fish are friends, not food,” they declare. A band of hippie sea turtles get Marlin and Dory closer to their goal by riding the East Australian Current. Bioluminescent deep sea fish nearly put the bite on our heroes, while a storm of jellyfish almost separate Marlin and Dory. Meanwhile, Nemo plots to escape the dentist’s office fish tank where he has been detained along with other captives—all determined to help Nemo get back to the ocean before he becomes a gift to the dentist’s niece, Darla (for Pixar, there’s nothing worse than a ginger-haired, brace-mouthed adolescent with a lack of sensitivity toward small things, as Toy Story confirms).

The film was written and directed by Andrew Stanton. A Pixar staple since they began producing features, Stanton served as a contributing writer on each release to that point, directing his first full-length film with A Bug’s Life. Like each of the earliest Pixar films, Finding Nemo’s story took several years to gestate and perfect. Stanton later explained the story’s origins: at his childhood visits to the dentist, he imagined the fish in the practice’s tank were yearning to escape to their ocean home. His fascination with ocean life continued through adolescence and into parenthood. While working on Toy Story in 1992, he took his five-year-old son to Marine World and became enthralled by the notion of animating undersea life with computers. At the same time, he noticed himself over-parent his son. “I spent the whole walk going, ‘Don’t touch this. Don’t do that. You’re gonna fall in there.’ And there was this third-party voice in my head saying, ‘You’re completely wasting the moment you’ve got with your son right now.’ I became obsessed with the idea that fear can deny a good father from being one.” When Stanton pitched the idea for over an hour to Pixar head John Lasseter, explaining his concept, its themes, and the undersea setting. Ever schmaltzy, Lasseter gave his decision: “You had me at ‘fish’.”

The film was written and directed by Andrew Stanton. A Pixar staple since they began producing features, Stanton served as a contributing writer on each release to that point, directing his first full-length film with A Bug’s Life. Like each of the earliest Pixar films, Finding Nemo’s story took several years to gestate and perfect. Stanton later explained the story’s origins: at his childhood visits to the dentist, he imagined the fish in the practice’s tank were yearning to escape to their ocean home. His fascination with ocean life continued through adolescence and into parenthood. While working on Toy Story in 1992, he took his five-year-old son to Marine World and became enthralled by the notion of animating undersea life with computers. At the same time, he noticed himself over-parent his son. “I spent the whole walk going, ‘Don’t touch this. Don’t do that. You’re gonna fall in there.’ And there was this third-party voice in my head saying, ‘You’re completely wasting the moment you’ve got with your son right now.’ I became obsessed with the idea that fear can deny a good father from being one.” When Stanton pitched the idea for over an hour to Pixar head John Lasseter, explaining his concept, its themes, and the undersea setting. Ever schmaltzy, Lasseter gave his decision: “You had me at ‘fish’.”

To prepare, the animators, engineers, and artists had to learn the entire ocean. Stanton and Lasseter arranged a series of reference points for everyone involved. They watched classic documentaries by Jacques Cousteau; they screened sea-related films like Steven Spielberg’s Jaws and James Cameron’s The Abyss; they watched the IMAX film Blue Planet. Lasseter purchased a fish tank and stocked it with saltwater fish for the animators, scheduled visits to local aquariums, and even arranged a scuba diving trip to Hawaii so the staff could better understand the undersea environment first-hand. Pixar also contains an in-house training department known as Pixar University, which booked lectures from marine biologists. One such lecturer was a postdoctoral fellow at Berkeley, fish expert Adam Summers, who noted that the Pixar team seemed more engaged and more interested than any graduate class he’d ever taught. “I couldn’t get more than three or four minutes of talking in before someone would raise their hand and ask a question that would send us off in all sorts of different directions.” Summers would eventually become a regular consultant on Finding Nemo, and the Pixar staff encouraged him to note flaws in how their animation represented marine life.

Summers was quick to note that real male clown fish will change their sex to female if the primary female in the school dies. Of course, Pixar couldn’t address the issue of gender reassignment within an animated film, at least not in the early 2000s, regardless of their interest in authentic marine life. Instead, the artistic staff dissected fish and invited additional lecturers to address all manner of subjects: algae, jellyfish, underwater plant life, waves, whales, and what happens to light under water. After animation had already begun on the coral reef sequences, the team learned kelp does not grow on coral reefs; at this, Lasseter ordered all reef sequences redone to remove kelp. Despite Pixar’s jealous commitment to the biological reality of fish, the film still had to be relatable to audiences. Fish were animated with their eyes at the front of their face, like a human, instead of on either side like a fish. Finding Nemo’s characters have a strange way of remaining true to their biological characteristics, while also offering recognizable ticks and movements drawn from human behavior. When Summers critiqued some of the more human behavior that Pixar had projected onto fish characters, he had to be reminded: fish don’t talk either.

Summers was quick to note that real male clown fish will change their sex to female if the primary female in the school dies. Of course, Pixar couldn’t address the issue of gender reassignment within an animated film, at least not in the early 2000s, regardless of their interest in authentic marine life. Instead, the artistic staff dissected fish and invited additional lecturers to address all manner of subjects: algae, jellyfish, underwater plant life, waves, whales, and what happens to light under water. After animation had already begun on the coral reef sequences, the team learned kelp does not grow on coral reefs; at this, Lasseter ordered all reef sequences redone to remove kelp. Despite Pixar’s jealous commitment to the biological reality of fish, the film still had to be relatable to audiences. Fish were animated with their eyes at the front of their face, like a human, instead of on either side like a fish. Finding Nemo’s characters have a strange way of remaining true to their biological characteristics, while also offering recognizable ticks and movements drawn from human behavior. When Summers critiqued some of the more human behavior that Pixar had projected onto fish characters, he had to be reminded: fish don’t talk either.

The animation crew was divided into six teams, each with sub-teams devoted to set modeling, shading, lighting, and water effects. Separate teams handled scenes at the Reef, the Sharks and Sydney, the above-water moments in Sydney, inside the whale where Marlin and Dory are trapped, the dentist’s fish tank, and the East Australian Current. Additionally, Pixar’s devoted character team was responsible for over 120 sea animals, birds (“Mine!”), and a few humans. As for voice talent, William H. Macy had originally recorded the lines for Marlin, but Stanton wasn’t satisfied with the effect and wanted a comic actor—he chose Albert Brooks, who lends his distinctive brand of neuroses (as seen in Lost in America and Defending Your Life) to the role. For Stanton, no one but Ellen DeGeneres could have played Dory; she inspired the character, as Stanton watched the actor’s talk show Ellen and noticed how she was “doing her shtick of changing the subject five times before a sentence finishes”. But Dory was more than a comic relief character, despite how closely tied DeGeneres and Dory were in Stanton’s mind. Her forgetfulness meant she had the innocence of a child, which in turn would teach Marlin some valuable lessons about taking risks for the ones you love.

Every detail looks accounted for by the Pixar staff, resulting in one of their most beautiful films. One can’t help but lose themselves in the gorgeous way light shimmers through the water to create beams of color that shift on the ocean floor and structures beneath the surface. Though at times the water doesn’t seem to contain much, look again: there are a million microscopic particles or bubbles painted into every scene, floating before us, even in the fish tank. Watch the way plant life never stops swaying with the motion of the water, or how fishy characters subtly surge with water’s movement in a static scene. To achieve this effect, Pixar modified their in-house program called Fizt, the same program that accounted for the lifelike movement of fur and cloth on Monsters, Inc. In fact, early demonstrations proved too realistic looking, to the degree that animated fish characters looked out of place in their photo-real world (a contrast intentionally employed on Pixar’s underrated The Good Dinosaur, from 2015). Stanton requested that his team reduce the photorealistic quality, reminding them they were making an animated film, not a documentary.

Every detail looks accounted for by the Pixar staff, resulting in one of their most beautiful films. One can’t help but lose themselves in the gorgeous way light shimmers through the water to create beams of color that shift on the ocean floor and structures beneath the surface. Though at times the water doesn’t seem to contain much, look again: there are a million microscopic particles or bubbles painted into every scene, floating before us, even in the fish tank. Watch the way plant life never stops swaying with the motion of the water, or how fishy characters subtly surge with water’s movement in a static scene. To achieve this effect, Pixar modified their in-house program called Fizt, the same program that accounted for the lifelike movement of fur and cloth on Monsters, Inc. In fact, early demonstrations proved too realistic looking, to the degree that animated fish characters looked out of place in their photo-real world (a contrast intentionally employed on Pixar’s underrated The Good Dinosaur, from 2015). Stanton requested that his team reduce the photorealistic quality, reminding them they were making an animated film, not a documentary.

During production in 2002, Pixar studios received a visit from Japanese master animator Hayao Miyazaki, whose Studio Ghibli had influenced both Disney and Pixar since his 1979 adventure Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro, on what the Pixar head called “Miyazaki Day”. Lasseter had been overseeing the English-language translation of Spirited Away, and would soon supervise English dubs of all Miyazaki films. Lasseter idolized Miyazaki, even as the two had met before and remained friends. He showed the Japanese director and his translator around the Pixar offices, visiting workspaces, and even their retro “Love Lounge” hidden behind air conditioning vents—a getaway space filled with retro décor. Lasseter and Miyazaki drove some vintage cars, Miyazaki met Lasseter’s parents, and that evening there was a charity benefit screening of Spirited Away. It remains appropriate that Miyazaki should tour Pixar’s HQ during their most Miyazaki-esque picture. After all, Finding Nemo contains the same attention to Nature and family as most Miyazaki films, appealing to virtually every demographic—a crucial characteristic of any Miyazaki work. (There’s even a sneaky commentary about treated sewage water being pumped into the ocean near Sydney, causing no end of pollution beneath the surface.) Everyone can find something to love inside Finding Nemo; the same can be said for Miyazaki’s Ponyo from 2009, an undersea story whose themes of Nature and family resonate on a similar frequency as Finding Nemo.

To be sure, Finding Nemo subjects the audience to a neverending string of dangers, strengthening its bonds of family and friendship. The tragic first scene where Marlin discovers his wife and children have become lunch challenges Up (2009) as perhaps the saddest prologue to any animated film. It’s also the glue that bonds Marlin to Nemo, and the audience to Marlin’s journey. In the face of a feeding frenzy, a torpedo detonating underwater mines, being nearly smashed by a sunken submarine, and almost losing Dory more than once, Marlin learns he cannot control these dangers, but rather must embrace and work through them. The most resounding theme in Finding Nemo remains the idea of letting young ones experience life and develop at their own pace. Crush, a sea turtle voiced by Stanton himself, offers this nugget of truth about parentage and knowing when children are ready for something: “You never really know. When they know, you’ll know, y’know?” Dory offers a slightly less wordy explanation: “You can’t never let anything happen to him. Then nothing would ever happen to him… Not much fun for little Harpo.”

To be sure, Finding Nemo subjects the audience to a neverending string of dangers, strengthening its bonds of family and friendship. The tragic first scene where Marlin discovers his wife and children have become lunch challenges Up (2009) as perhaps the saddest prologue to any animated film. It’s also the glue that bonds Marlin to Nemo, and the audience to Marlin’s journey. In the face of a feeding frenzy, a torpedo detonating underwater mines, being nearly smashed by a sunken submarine, and almost losing Dory more than once, Marlin learns he cannot control these dangers, but rather must embrace and work through them. The most resounding theme in Finding Nemo remains the idea of letting young ones experience life and develop at their own pace. Crush, a sea turtle voiced by Stanton himself, offers this nugget of truth about parentage and knowing when children are ready for something: “You never really know. When they know, you’ll know, y’know?” Dory offers a slightly less wordy explanation: “You can’t never let anything happen to him. Then nothing would ever happen to him… Not much fun for little Harpo.”

This appreciation has said much about the animation and narrative insightfulness of Finding Nemo but little of its sense of humor. Consider how “Harpo” belongs on a list of Dory’s scatterbrained names for Nemo, alongside Chico, Fabio, Bingo, and so on. DeGeneres perfectly performs Dory’s hilarious, if occasionally tragic, short-term memory loss. The bright and optimistic Dory gives Marlin a constant headache. There’s also an ongoing joke about everyone in the ocean believing Marlin should be funny, since he’s a clown fish. Because an established comedian of Brooks’ caliber voices him, Marlin’s failed attempts to tell his one-and-only joke become doubly funny. As his audience listens to Marlin over explain the joke’s setup, their expectant smiles gradually fall from their faces. And for a G-rated film, a preponderance of scatological humor does not overlook the gross reality of fish tank life, and yet somehow remains tasteful. When the tank’s inhabitants jam the filter as part of their escape plan, one of the fish announces, “Doesn’t anyone realize? We’re swimming in our own sh…” Another fish cuts in—“Shh!”

With plenty of humor and tear-inducing emotions for its cast of three-dimensional animated characters, the film’s subject of parental anxiety resulted in an uncommon, exceptional delight. As Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times noted, Finding Nemo would establish Pixar as “the most reliable creative force in Hollywood”, a mantle the studio would not take lightly. Finding Nemo was followed by equally imaginative and praiseworthy efforts like Brad Bird’s The Incredibles (2004) and Ratatouille (2007), and perhaps Pixar’s finest work of art, Stanton’s 2008 masterpiece WALL·E. More than most other Pixar releases, Finding Nemo retains a place in its audience’s mind and remains there still—an undeniable instant classic in its day, and a classic still. An astonishment rarely equaled in animation, the film’s universality transcends the aspirations of typical animation to achieve something unique to Pixar—the Pixar Touch, as it has been called. Offering its fifth triumph out of five attempts, Pixar’s Finding Nemo elevated their already visionary and pioneering output to the thematic level of Hayao Miyazaki, engaging the imagination of children and their parents with the dangers and beautiful wonders of Nature and the supportive love of family.

With plenty of humor and tear-inducing emotions for its cast of three-dimensional animated characters, the film’s subject of parental anxiety resulted in an uncommon, exceptional delight. As Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times noted, Finding Nemo would establish Pixar as “the most reliable creative force in Hollywood”, a mantle the studio would not take lightly. Finding Nemo was followed by equally imaginative and praiseworthy efforts like Brad Bird’s The Incredibles (2004) and Ratatouille (2007), and perhaps Pixar’s finest work of art, Stanton’s 2008 masterpiece WALL·E. More than most other Pixar releases, Finding Nemo retains a place in its audience’s mind and remains there still—an undeniable instant classic in its day, and a classic still. An astonishment rarely equaled in animation, the film’s universality transcends the aspirations of typical animation to achieve something unique to Pixar—the Pixar Touch, as it has been called. Offering its fifth triumph out of five attempts, Pixar’s Finding Nemo elevated their already visionary and pioneering output to the thematic level of Hayao Miyazaki, engaging the imagination of children and their parents with the dangers and beautiful wonders of Nature and the supportive love of family.

Bibliography:

Auzenne, Valliere Richard. The Visualization Quest: A History of Computer Animation. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994.

Price, David A. The Pixar Touch. New York: Knopf, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review