The Definitives

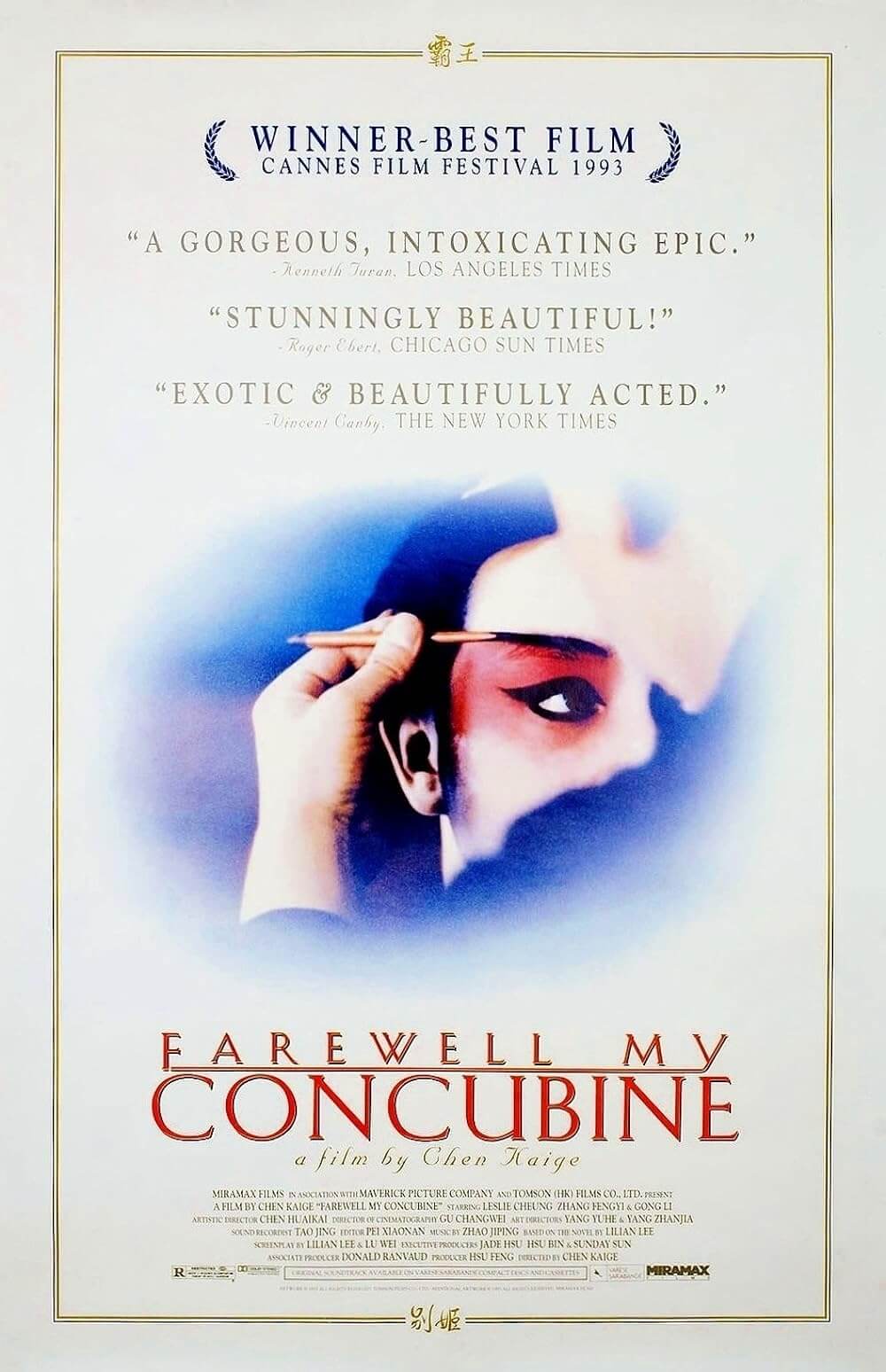

Farewell My Concubine (1993)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

An epic about two Peking opera stars that spans fifty years of Chinese history, Farewell My Concubine explores the relationship between life and art, power and performance, and how they become indistinguishable. Based on a novel by Lilian Lee, the film uses its subject matter as a literal and symbolic text to talk about the past. Chen Kaige’s 1993 breakthrough can be seen through many frameworks: a backstage drama about the Peking opera; a chronicle of paradigm shifts in China throughout the twentieth century, which caused people to struggle under the demands of various political powers; a metaphor that links the stage with the necessity for people to endure China’s regime changes through performance; a queer-coded study of a complex stage actor; and a dramatic parallel for the life of star Leslie Cheung. Through this subject matter, the film’s rich intertextuality conveys and rethinks Chinese history, literary traditions, and conventional representations of gender and sexuality with a post-modern tendency for adaptation and critique. Yet, regardless of its considerable ambitions, Farewell My Concubine boasts elegant and sumptuous filmmaking, resulting in a staggering unity of theme, structure, and mise-en-scène. The film’s sophisticated approach to intricate characters and political turmoil represents not only a landmark that helped introduce Chinese cinema to the world, but an unforgettable experience that combines psychological depth with the visual scope of an epic.

Produced for Beijing Film Studio with financial backing from Taiwan by way of Hong Kong, the film unfolds against China’s tumultuous twentieth century: the Warlord Era in 1924; the Japanese invasion in 1937 and subsequent Occupation; the Japanese surrender in 1945; the Chinese Nationalist Party’s retreat to Taiwan, leaving mainland China to the People’s Republic of China in 1949; the Great Leap Forward; and the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Although the sweeping historical panorama covers war, revolution, and cultural change, Chen never allows his spectacle to outweigh his treatment of the characters. However, his sense of historicity, combined with the film’s portrait of the Peking opera, represents an alternative to the majority of Chinese cinema to this point. Chinese film scholar Luo Hui notes a direct correlation between Chinese theater and cinema since the earliest Chinese films, many of which merely captured traditional stage productions and performances on celluloid. When Hollywood imports detailed a method of creating a screen space grounded in realism (or at least movie realism) instead of theatrical subjects and visual symbolism, many Chinese filmmakers tested these methods. But the vast majority of mainland China’s film output consisted of stagey productions, state propaganda, and modest depictions of everyday life. Gradually, Chinese filmmakers replicated a Western method of scopic visual storytelling. In 1993, Chen’s film received overwhelming praise on the international stage in part because of its familiar Western mode of the historical epic, which proves universally recognizable given the saturation of Hollywood film products across the globe.

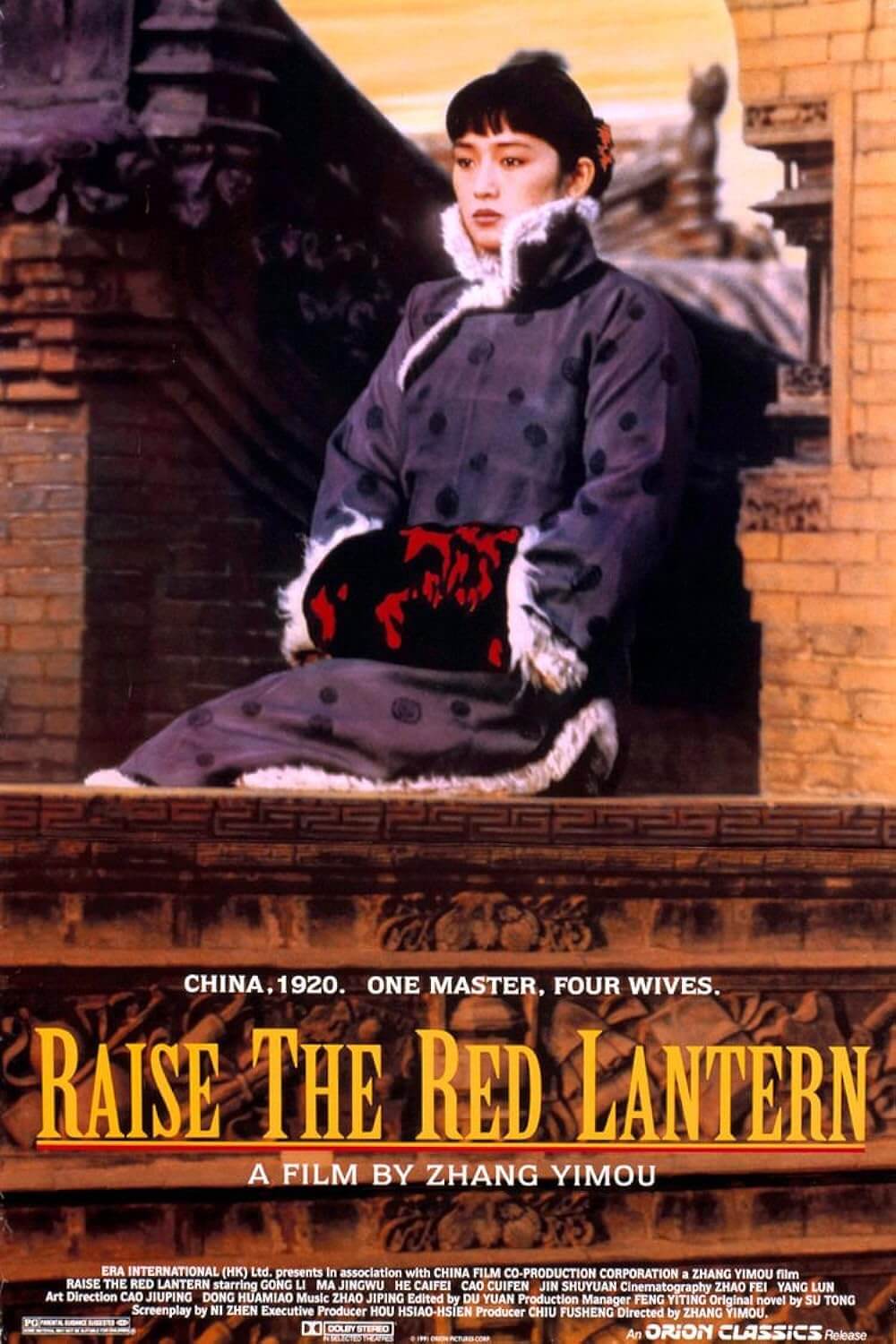

Chen Kaige first became interested in Farewell My Concubine when producer Hsu Feng (once a regular in the wuxia films of King Hu) gave him a copy of Lilian Lee’s book at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival. Chen, one of the most celebrated of all Chinese filmmakers, was among the first students to enroll in the Beijing Film Academy when, in 1978, it reopened after its 12-year closure during the Cultural Revolution. He studied alongside future greats Zhang Yimou (Raise the Red Lantern, 1992) and Tian Zhuangzhuang (The Blue Kite, 1993), among others. Their graduating class, known as China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, forever changed their country’s national cinema. Like many of his classmates, Chen spent his youth during the Cultural Revolution divided between working in the countryside—chopping down trees in Xishuangbanna prefecture in the southwestern Yunnan province—before transferring to five years of military service. After colleges reopened, Chen applied to the Film Academy, following his parents’ footsteps (his father was director Chen Huai’ai, and his mother was Liu Yanchi, who worked on scripts at Beijing Film Studio). When he graduated in 1982, his first film was Yellow Earth (1984), shot by cinematographer Zhang Yimou. Yellow Earth signaled a significant shift in Chinese cinema, moving away from the heavily propagandistic works after the Communist Revolution of 1949 into filmmaking concerned with symbolism, equivocations, and historical critiques—techniques considered radical compared to earlier state-sanctioned cinema. And over the years, Chen continued making some of the most well-received films among his Fifth Generation peers, including Life on a String (1991) and The Emperor and the Assassin (1999).

Farewell My Concubine opens in 1977, with a spotlight on Cheng Dieyi (Leslie Cheung) and Duan Xiaolou (Zhang Fengyi), two performers trained in the Peking opera. For the first time since the Cultural Revolution, 22 years earlier, they reunite to rehearse the stage play that made them famous. Then the film flashes back to 1924 when Dieyi’s mother tries to sell her child to an opera troupe, knowing he cannot stay at her brothel. However, the rigid instructor, Master Guan (Lü Qi), refuses to accept Dieyi because he has an extra finger next to his pinky, prompting Dieyi’s mother to chop it off and deliver him to the school. Initially bullied, Dieyi makes close ties with fellow student Xiaolou—his replacement mother and future companion—and together, they endure Master Guan’s harsh instruction and physical beatings. Finally, after lessons and punishment over the formal rigor of opera, Dieyi and Xiaolou, nicknamed Douzi and Shitou, make their debut performance for the imperial eunuch, acting out the traditional Chinese opera Farewell My Concubine. Pleased with the performances and drawn to Dieyi’s convincing feminine appearance as the Concubine, the eunuch demands to see him afterward and then forces himself on the boy. Shattered by the assault, Dieyi finds an abandoned infant boy that same night and vows to raise him in the troupe under the name Xiao Si.

By 1937, Dieyi and Xiaolou are celebrated Beijing opera stars, widely known as Concubine and King, and inseparable from their stage roles in the public eye. Dieyi, now a narcissistic yet supremely talented jingju performer who forsakes all else for his art, attracts the obsessive Yuan Shiqing (Ge You), an arts patron who wins Dieyi’s attention with lavish stage jewelry. At the same time, Xiaolou finds himself rescuing Juxian (Gong Li), a prostitute who wants a new life. She buys her way out of her brothel and marries Xiaolou, forcing a wedge between her husband and his jealous stage partner. But Dieyi and Xiaolou’s unspoken offstage marriage as Concubine and King is central to their popularity, and Juxian threatens that. “Have you forgotten about the secret to our success?” asks Dieyi. Betrayed, Dieyi considers suicide but turns to Yuan Shiqing and opium out of despair. Soon the Japanese army occupies Beijing and takes Xiaolou into custody for attacking a Japanese officer. Learning that a Japanese commander enjoys his work, Dieyi arranges for a private performance to ensure Xiaolou’s release. But when the Nationalist Party comes into power after the occupation, they put Dieyi on trial for treasonously performing for the Japanese. After much wrangling, Juxian blackmails Yuan Shiqing to testify on Dieyi’s behalf. Regardless, Dieyi refuses to help himself and, seemingly doomed to prison, earns his freedom because a Party official requests to see him perform.

In 1949, the political climate shifts dramatically. The Communist party arranges to execute Yuan Shiqing and condemns the extravagance of the Peking opera. The baby Dieyi rescued is a young adult by this time, and Xiao Si (Lei Han) has bought into the revolutionary spirit and resents Dieyi’s sense of artistic superiority, championing a grounded and undramatic propaganda theater. Juxian and Xiaolou attempt to conform. “You have to go along with it,” Xiaolou tells Dieyi. “What else can you do?” But with the Cultural Revolution in 1966, their conformity must become unwavering obedience, and their past becomes the target of harsh judgment. Though Xiaolou and Juxian destroy their possessions to hide any evidence of their past, Xiao Si, now a figure in the Red Guard, arranges for a public trial of the three main characters. Under torturous conditions, Xiaolou informs on Dieyi, exposing him as a traitor obsessed with opera and in a sexual relationship with Yuan Shiqing. In the fiery scene, Dieyi retaliates and calls out Juxian’s former life as a prostitute, which Xiaolou confirms, claiming, out of self-preservation, that he never loved Juxian. After their mutual betrayals, Juxian kills herself. Years later, we again see Dieyi and Xiaolou rehearsing in 1977, reunited for the first time since Juxian’s suicide. In their final performance, Dieyi the Concubine draws Xiaolou the King’s sword and kills herself.

The titular opera, sometimes called The Hegemon-King Bids His Lady Farewell, debuted in Beijing in 1921 and dramatizes the conflict between King Xiang Yu of Chu and Liu Bang of Han in 202 BCE. Although many adaptations of King Xiang Yu’s fate appear in Chinese literature and drama, Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian supplied the first account in Records of the Grand Historian, published in 91 BCE. Most early retellings of the tragedy place the doomed Xiang Yu in the central role. Lamenting his inevitable defeat by the future Emperor, Xiang Yu resolves not to flee his enemy and kills himself. His Concubine’s fate goes unmentioned in the original story, though Xiang Yu wonders if she will defect or meet a grim death. Later in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), after the account went through several adaptations, the story’s focus shifted to the Concubine in the play A Thousand Pieces of Gold. In this retelling, the Concubine declares her loyalty to her King, who hands over his sword so that she may cut her throat before him. Centuries later, when Mei Lanfang, the renowned actor of female roles on whom Cheng Dieyi was loosely based, performed the opera in 1921, he removed any question of the Concubine’s allegiance and turned her death into the ultimate expression of loyalty. In Mei’s version, when Xiang Yu orders his Concubine away, she defies her King’s orders and stays. After dancing for him one last time, she deceives the King, takes hold of his sword, and ends her life before he can stop her.

Both the Concubine’s dance and the King’s sword in Mei’s version symbolize unwavering devotion and righteousness—themes that inform Chen’s Farewell My Concubine, in the way Dieyi and Xiaolou’s relationship either mirrors or deviates from the opera. Life imitating art is one of the film’s central themes. Throughout the film, Dieyi places himself in dangerous situations for Xiaolou or the integrity of his performance, playing out his role as a selfless Concubine committed to the King. However, Dieyi’s arrogance betrays that selflessness at times, given the complex gender and sexual dynamics that emerge. Starting from Lilian Lee’s novel, Farewell My Concubine uses the filmic medium to comment on and complicate the original Chinese opera, expanding on the subject from layered psychological, political, and cultural perspectives. It is interesting that David Cronenberg’s M. Butterfly, also released in 1993 and also about a queer-coded Peking opera performer, takes a similar intertextual approach. In Cronenberg’s case, the screenplay’s source of David Henry Hwang’s 1988 play M. Butterfly borrowed from Giacomo Puccini’s 1904 opera Madame Butterfly. Both Chen and Cronenberg’s films are adaptations of revisionist texts that adopt the name of an original opera, using them as a corresponding narrative framework against which the respective films deviate and draw from in fascinating ways.

To further complicate Farewell My Concubine’s intertextuality, Lilian Lee’s novel was not the first time she had told this story. Four years before the prolific writer published her book, she put the material into a screenplay for Hong Kong television, directed by Alex Law. However, when Chen set out to adapt Lee’s novel, he discovered the Hong Kong author “didn’t have a very clear grasp of the situation in China or the world of the Peking opera. She didn’t have any real emotional understanding of the Cultural Revolution, either.” Furthermore, Lee’s take on the story had been curbed by Hong Kong publication standards, constraining her writing with a page limit. Hoping to expand upon the book, Chen enlisted Lu Wei, a mainland writer from the Van Film Studio. Together with Lee, they devised a new script that better addressed the story’s historical scope and complex character motivations. After completing work on the script in 1991, Lee set out to rewrite her novel given her new understanding of Chinese history. To help promote the film’s release, she republished her novel in 1992 with a page count of more than double the original version. And so, Chen’s film of Farewell My Concubine has a tangled origin wrapped in Chinese history, opera, and literature.

To further complicate Farewell My Concubine’s intertextuality, Lilian Lee’s novel was not the first time she had told this story. Four years before the prolific writer published her book, she put the material into a screenplay for Hong Kong television, directed by Alex Law. However, when Chen set out to adapt Lee’s novel, he discovered the Hong Kong author “didn’t have a very clear grasp of the situation in China or the world of the Peking opera. She didn’t have any real emotional understanding of the Cultural Revolution, either.” Furthermore, Lee’s take on the story had been curbed by Hong Kong publication standards, constraining her writing with a page limit. Hoping to expand upon the book, Chen enlisted Lu Wei, a mainland writer from the Van Film Studio. Together with Lee, they devised a new script that better addressed the story’s historical scope and complex character motivations. After completing work on the script in 1991, Lee set out to rewrite her novel given her new understanding of Chinese history. To help promote the film’s release, she republished her novel in 1992 with a page count of more than double the original version. And so, Chen’s film of Farewell My Concubine has a tangled origin wrapped in Chinese history, opera, and literature.

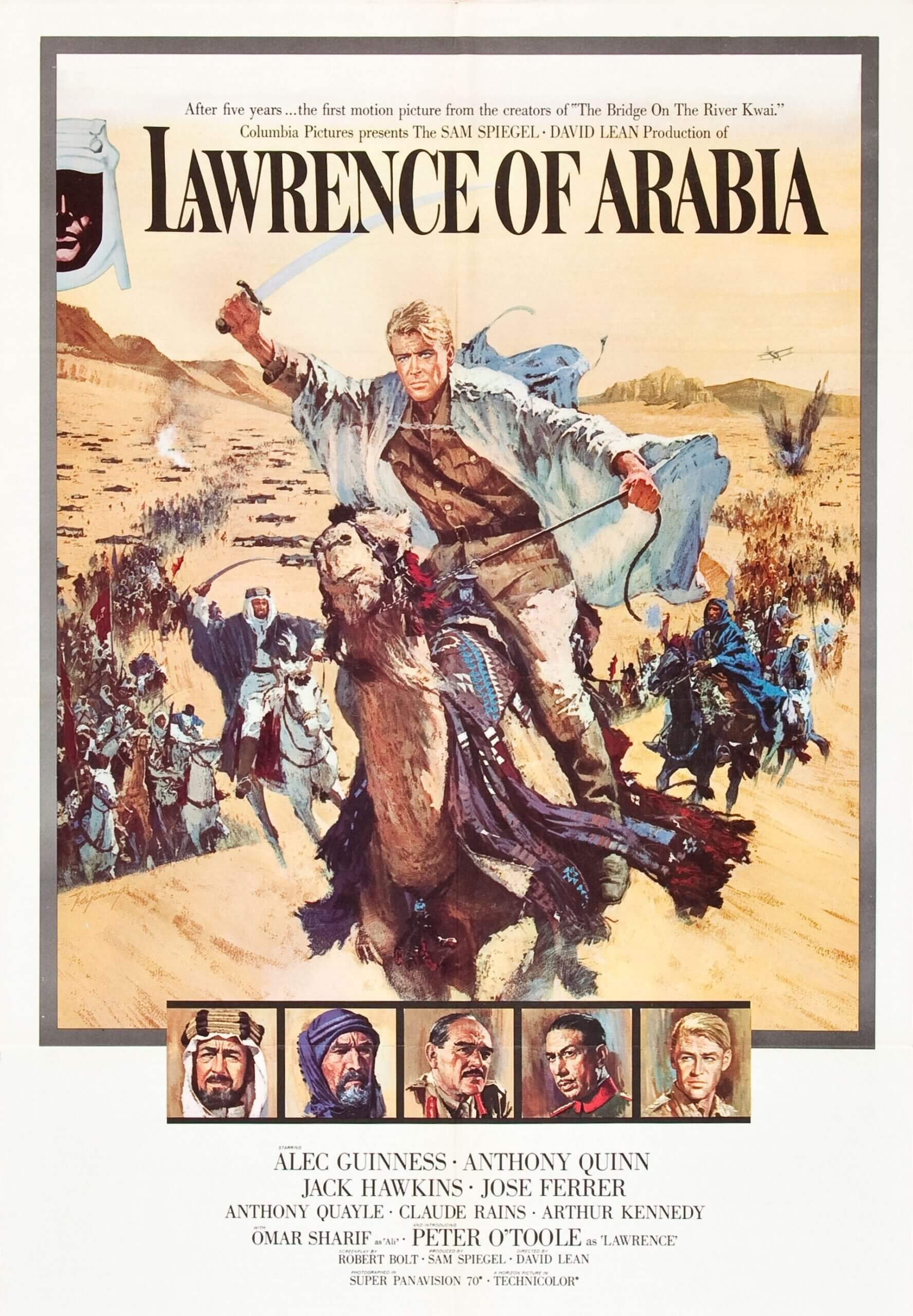

Moreover, Chen’s influences go beyond Chinese sources. Despite the Chinese Communist Party frowning upon the impact of Western films, the Beijing Film Archive afforded Chen access to see many international films, including those by David Lean. The director told Cinéaste in 2003 that his favorite film is Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Drawing from that model, elements of Lean’s sprawling humanist epic in Farewell My Concubine become apparent: both feature a cryptic protagonist whose sexuality and ambition prove ambiguous; both span decades and showcase a turbulent period of history; both pay equal attention to visual beauty and character study; both contain their story in a lengthy runtime, giving the narrative a certain grandeur. The film also represents a break from Chen’s style at this point in his career. Before Farewell My Concubine, Chen’s aesthetic was known for what scholar Sheila Cornelius described as “seemingly meandering narrative structure and wanton obscurity.” If his films in the 1980s tended to be allegorical and abstruse, his adaptation of Lee’s book focused attention on character arcs, lavish spectacle, and heightened interpersonal conflicts in the manner of Lean. Many Fifth Generation filmmakers like Chen eventually set aside their early career aesthetics to make a drive toward commercial coproductions financed by Hong Kong or Taiwan and distributed internationally. But Chen’s transregional production blends aesthetics, historical scope, and genuine emotions for a rare epic that does not sacrifice its artistic integrity for its commercial success.

When Farewell My Concubine debuted at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival, it became the first Chinese production to win the Palme d’Or (shared with Jane Campion’s The Piano). Afterward, Chen’s film opened in Shanghai in July 1993 for a brief run. But censors in China’s State Administration for Radio, Film and Television pulled the film from theaters, citing its “attitude problems” and bleak assessment of the Communist ideology. Their censorial review lasted a few weeks. Meanwhile, the public outcry on an international scale convinced Chinese officials to remove the ban, concerned that the negative press would affect their campaign to host the 2000 Olympics in Beijing. However, the newly distributed film was not the version that screened at Cannes. Censors removed allusions to queerness and suicide in the recut version. In addition, Chinese officials took issue with Cheng Dieyi—not only his implied sexuality but his suicide in 1977, after the Cultural Revolution and during a comparatively stable time in China’s history. The act was considered “politically unacceptable,” according to Cheng in Cinéaste. The film faced entirely different cuts from Miramax’s Harvey “Scissorhands” Weinstein in the US and UK. Weinstein reduced the runtime from 171 minutes to 154 minutes in a version that “doesn’t make any sense,” according to French director Louis Malle, head of the awarding Cannes jury that year. Even so, it went on to earn Academy Award nominations for Best Cinematography and Best Foreign Language Film, and it has since been ranked among the greatest of all international films.

Decades after the film’s release, its intertextuality, representation of Chinese culture and history, and the portrait of multifaceted characters—none more intricate than Cheng Dieyi—still supply a rich text for analysis, particularly concerning gender and sexuality. Consider how Dieyi, a character given to affairs with men and onstage cross-dressing, has a series of performative roles thrust upon him during childhood. When he first appears as a boy, his mother has dressed him like a girl to disguise his presence in the brothel. He begins training under Master Guan, learning to inhabit female opera roles (dan). The practice, established during the Ming and Qing dynasties to limit the interactions between men and women on the stage, also led to identity issues and allusions to same-sex relationships, regardless of Chinese society’s prominent binary gender structure at the time. Still, Dieyi learns gender pluralism during the punishing lessons with Master Guan. When Dieyi repeatedly misremembers the opera line “I am by nature a girl, not a boy” by inverting the pronouns, he receives beatings, even one from Xiaolou. Finally, Dieyi remembers the line and, afterward, loses himself in feminine roles, blurring his distinction between onstage feminine traits and offstage masculine traits.

Farewell My Concubine has been discussed as a site of queer subjectivity by scholars, such as Helen Hok-Sze Leung’s monograph calling the film “A Queer Film Classic.” E. Ann Kaplan notes the film’s rather “stereotypical representation of homosexuals” with “effete” characteristics in the film, but also acknowledges that Chinese cinema at the time had “only just begun to deal with gay sexualities,” so the film “should be recognized as progress.” During both the film’s period and its release in 1993, Chinese culture considered openly queer relationships controversial. Beginning with Deng Xiaoping’s reform agenda in 1979, China deemed them criminal “hooliganism” before their decriminalization in 1997. But Farewell My Concubine resists defining Dieyi’s sexuality in certain terms, resulting in a pluralistic understanding of the character, reflecting his onstage and offstage duality. “Has he not blurred the distinction between theater and life, male and female?” asks an admiring instructor of Yuan Shiqing, who watches, obsessed with Dieyi’s embodiment of the Concubine. Later, during a private meeting in his home, Yuan Shiqing tells the actor, “Only the bodhisattva embraces both male and female essences,” suggestively calling the state “such ecstasy.” The two become lovers, observed in allusive scenes where Yuan Shiqing touches Dieyi’s shoulders from behind, places his fingers on his lips, and applies stage makeup to him. The closest the film comes to labeling these gestures comes when Xiaolou outs Dieyi during the Cultural Revolution, declaring that Dieyi “became Yuan Shiqing’s—.” Xiaolou never expresses certain words, but the implication is unmistakable.

The question of the nature of Dieyi’s identity reverberates throughout Farewell My Concubine, and while most critics praised the film, many scholars took issue with Chen’s work. Noting that its commercial success on the international market represented an artistic step back from Yellow Earth, detractors felt Chen sought to appeal to Western audiences. Scholar Wendy Larson argued that Fifth Generation filmmakers have used the visual iconography of concubines and theater subjects as a mode of “feminization” and subjugation to appease Western fantasies about the East, and that Dieyi’s queer identity makes him palatable to Western viewers. Similarly, Luo Hui called the film an “Orientalist spectacle” by playing into Western stereotypes about Chinese culture. After all, Chen spent his share of time in the Western film community. Besides his time as a visiting scholar at the New York University Film School in the 1980s, Chen also shot a music video for Duran Duran and later directed the disastrous English-language thriller Killing Me Softly (2005). Combined with Chen’s interest in Western cinema, this demonstrates that Chen had been exposed to Western ideologies and modes of representation. Such readings suggested to critics that Chen catered his film to international demands. Most Fifth Generation directors intended their films for mainland China only to see them banned, which led to a common complaint about their work becoming increasingly commercial over time to avoid such treatment from censors. But there is a tendency among Western critics to read the films of other nations through their own lens—their ideologies, theories, and moral prejudices. Yet, certain themes and emotions remain universally human: the trauma of abandonment, our tendency to use art to understand ourselves, and art imitating life.

Dieyi’s identity extends beyond standard queer subjectivity through the complicated facets of his relationship with Xiaolou in psychoanalytic terms. Kaplan associates Dieyi with Freud’s “abandonment neurotic,” who is “ever seeking to refind or replace the mother who left him but always anticipating rejection.” That sense of inevitable rejection feeds into Dieyi’s fatalism and attraction to his Concubine character, who accepts her fate with the grace of a refined stage performance and historical icon. By constantly inhabiting the Concubine role, Dieyi employs a permanent self-defense mechanism, thus lending his performance a convincing quality that has made him a renowned actor. Pain as performance softens or altogether protects Dieyi from confronting the source of his actual pain—what Freud would argue amounts to twofold castration: first Douzi’s extraneous finger, then his abandonment by his mother. Going to such lengths as Dieyi does to protect himself, it’s worth questioning whether Dieyi’s deeply implied relations with Yuan Shiqing or love for Xioalou were part of his continuous Concubine performance or genuine queer desire or both. Helen Hok-Sze Leung logically observes that Dieyi is not strictly a gay man and notes the film does not provide “realistic or positive images of gay and transgender lives in the present day. Rather, the film shows us a queer way of being that we can barely recognize, that may even offend our modern sensibilities, but that deserves to be remembered and understood in all its human complexity.”

Furthermore, Dieyi’s relationship with Xiaolou takes the form of many different relationship structures. When Dieyi’s mother first leaves him at the school, Xiaolou replaces Dieyi’s mother as a caretaker, creating a parent-child dynamic as Xiaolou defends the newcomer from student bullying and torment from the instructors. Onstage and inhabiting their roles as King and Concubine, their relationship is one of devoted lovers, while offstage, Dieyi and Xiaolou refer to each other as “stage brothers.” Before Juxian enters the picture, the two men even behave intimately behind closed doors in their shared dressing room. After a performance at the height of their popularity in 1937, Chen shows Dieyi tickling Xiaolou until they pause in a loaded moment interrupted by visiting admirers. At this point, they promptly separate—both aware of what the scene looks like. When Xiaolou introduces Juxian into their dynamic, Dieyi sees their union as a symbol of what he never had with his mother and what he could never have with Xiaolou except on stage. Like his mother, Juxian works in a “House of Blossoms” when they first meet. He dreads Juxian and Xiaolou’s marriage and their inevitable child, who will have what he never could. Dieyi sees life working out for the couple, reminding him of what he lost. Their relationship also takes Xiaolou away from Dieyi. Thus, Dieyi responds both as a child whose single parent has found a replacement partner and a scorned lover, rejecting Juxian out of layers of jealousy and resentment. To be sure, Dieyi and Xiaolou’s relationship exists on levels of mother and child, siblings, husband and wife, and separated lovers. Metaphors aside, they are stage partners, collaborators, and fellow actors—a professional duo intractable from one another in the public eye. They are also lifelong friends. Yet, each of these states creates fascinating complications in the film’s drama.

Equivocations regarding Dieyi’s subjectivity aside, Farewell My Concubine has been embraced in recent years as a queer film in no small part because of actor Leslie Cheung, whose life mirrors that of his onscreen character. Chen confirmed as much when he told Cinéaste about first meeting the actor to play Dieyi: “We met in Hong Kong to discuss the role. He was sitting there quietly, smoking a cigarette in the most arrogant manner—I’ll always remember that. After I told him Concubine’s story, he just said, ‘That’s me.’” Although Chen initially considered John Lone, creative differences between the director and Lone forced Chen to consider someone else. He coaxed Cheung out of early retirement from his new home in Vancouver. A best-selling Cantopop star and queer icon, Cheung’s celebrity personifies Hong Kong’s rise to prominence in the glory days of the 1980s and 1990s, and he mirrored its decline in the early 2000s. After dominating the Cantopop charts in the ’80s, Cheung retired from music and committed to his acting career. He worked with some of Hong Kong’s greatest directors—including Wong Kar-wai, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Ronny Yu on films such as A Better Tomorrow (1986), Rouge (1987), Days of Being Wild (1991), and Happy Together (1997). He also defied the norm and openly talked about his bisexuality with the press, making him a hero in LGBTQ+ circles. Burning as bright as Cheung’s celebrity did, he suffered from depression. Not long after the SARS outbreak and protests against Article 23 of the Basic Law, signaling a dramatic downswing in the people of Hong Kong’s trust in their government, Cheung committed suicide by leaping from the 24th floor of Hong Kong’s Mandarin Hotel in 2003. Upon reflection, the act cannot help but feel linked to Dieyi’s tragic fate.

Most of the discussion about Farewell My Concubine in critical and scholarly circles dwells on Dieyi and Xiaolou or the queer (or not) subjectivity of Dieyi. However, Juxian supplies a pivotal figure as well. After casting Gong Li, who earned international renown from several collaborations with Zhang Yimou, Chen expanded the book’s minor character. His version of Juxian amplifies the love triangle at the film’s center and parallels the same suffering experienced by China during the film’s five-decade portrait. Indeed, writing in The New York Times, Caryn James described the film as “a metaphor for the identity crisis of China itself” throughout the cultural and political shifts portrayed in the film. Consider how the love triangle and China coexist, neither one encompassing the other but complementing each other in the way they both thrive, suffer, experience violent change, and remain traumatized. As noted by scholar Luo Hui, Xiaolou is caught between Juxian’s grounded practicality and Dieyi’s unbridled artistic passion, between doing what he must to survive the cultural changes and embracing his desire to perform. Juxian, a survivor, compels her husband to change with the political tide, while Dieyi’s commitment to his art places creative pressure on Xiaolou. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Juxian endures, even after tragically losing her child during a protest against a stage performance. Chen does not dwell on the child’s death because Juxian does not. Though Juxian is not a stage performer, she conforms to each new regime change like a masterful actor, linking how performance is essential to survival during this period. Their triangle ends after Dieyi and Xiaolou confess during the Cultural Revolution, betraying Juxian. Finally, their triangle is severed when Juxian drops a sword near Dieyi and, realizing she can never penetrate their interplay of reality and performance, hangs herself.

The sword symbolizes Dieyi and Xiaolou’s relationship, going back to their childhood under Master Guan. They first discover it after their performance for the imperial eunuch. “The Chu king would have won with this sword,” Xiaolou tells Dieyi. “If I were emperor, then you’d be queen of the palace.” Dieyi interprets this to mean that if only Xiaolou possessed the sword, they could be together like their King and Concubine counterparts. Dieyi responds, “I want you to have a sword like this.” Years later, as adults, just after Xiaolou announces he will marry Juxian, Dieyi discovers that Yuan Shiqing has acquired the sword from the now-bankrupt eunuch. Yuan Shiqing offers the blade in exchange for Dieyi becoming his “intimate friend.” Dieyi makes the sacrifice, and when he delivers the sword to Xiaolou, he’s heartbroken to discover that Xiaolou no longer remembers the sword’s significance: “We’re not on stage. What would I want with a sword?” Still, Xiaolou keeps the blade, and Juxian uses it to compel Yuan Shiqing to testify on behalf of Dieyi when state officials charge him with treason. Despite being the third wheel in Dieyi and Xiaolou’s relationship, she recognizes the importance of the sword. During the Cultural Revolution, Juxian recovers it from a pile of burning theater props. And after Xiaolou publicly betrays her, she returns the sword, as if turning Xiaolou back over to Dieyi. When Dieyi and Xiaolou rehearse their roles one last time in 1977, Dieyi uses the sword to kill himself, bringing Dieyi’s life and performance together with an object that has defined his tragic, lovelorn relationship with Xiaolou.

Farewell My Concubine would not be what it is without Chen’s striking visual interpretation. Although Chen could have given the film a larger-than-life theatricality, he visualizes the story in gorgeous compositions conceived with cinematographer Gu Changwei—images worthy of the stage yet presented as cinema. Naturally, given the subject matter, operatic colors and costumes convey vibrant reds, golds, and whites. But there’s also a rich technique behind Chen’s approach; each shot appears thought out, as though the camera hadn’t just captured something unplanned but had chosen the ideal perspective for every setup. This is a film of intentional and vibrant imagery: Note the repetition of shadows, silhouettes, and beams of light. Note the disorienting camerawork that tilts in frantic moments, such as Dieyi’s delivery to the opera school or trial during the Cultural Revolution. Note Dieyi’s opium-fuelled hallucinations that mistake a semitransparent screen as moving goldfish. And perhaps the most resonant and enduring visual motif resides in Chen’s use of mirrors. They appear in Dieyi and Xiaolou’s dressing room, where the two regard each other, and later when Xiao Si dresses in the Concubine’s costume, evidently jealous and fascinated by Dieyi’s iconic appearance. Mirrors symbolize the way art reflects life and vice versa in the film, while presenting a reflective surface to examine identity. What does Dieyi see when his image is reflected back at him, the Concubine, the actor, or the little boy abandoned by his mother? The unity of image and meaning in Chen’s work, combined with the depth of character, further reinforces Chen’s approach to David Lean.

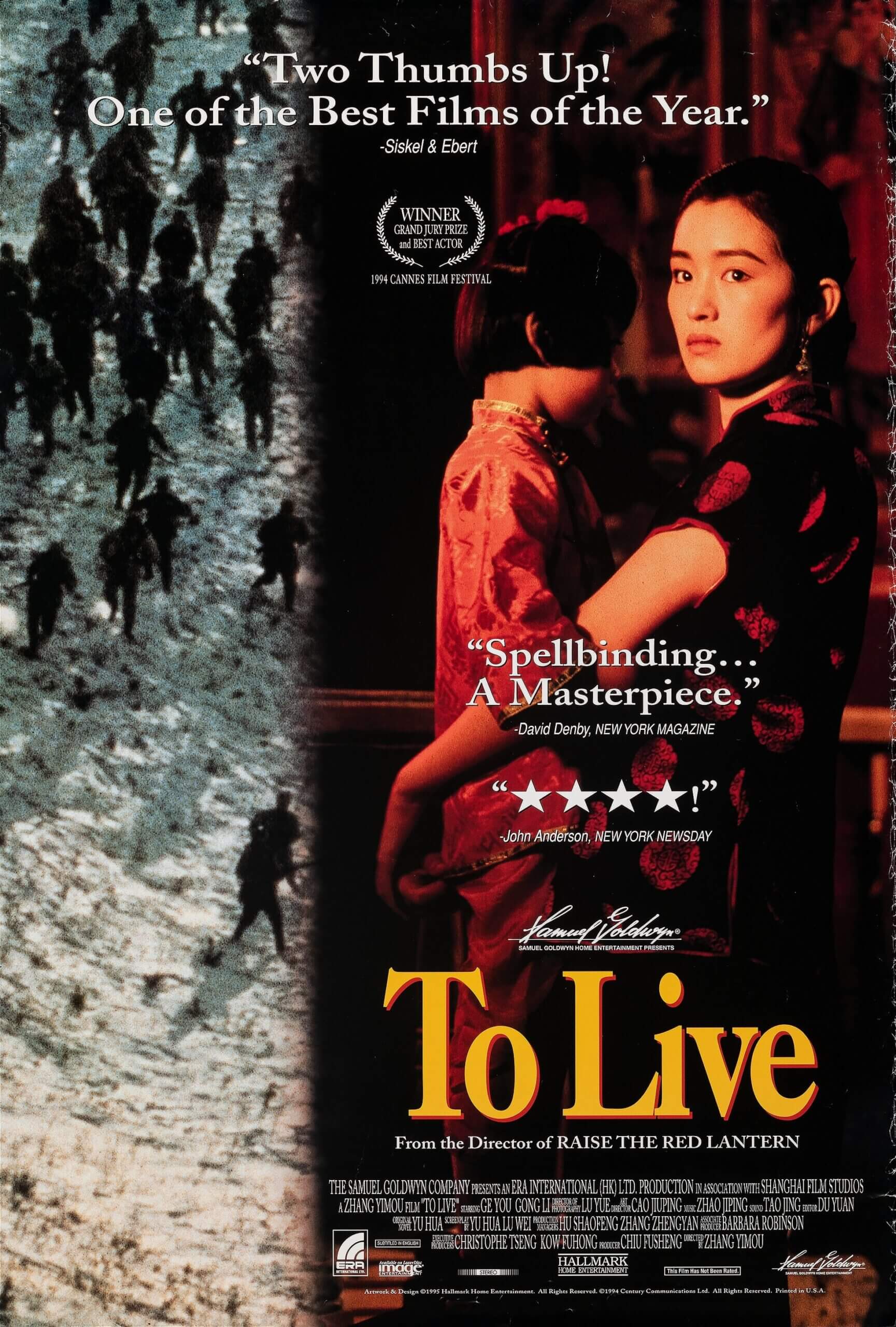

In Chen’s remarks to Western journalists around Farewell My Concubine’s release, the director fuels the association between his film and Lean-style epics. Larson notes that he draws from his personal experiences during the Cultural Revolution, using the film to explore his anger about feeling “duped” by the Chinese state, which made victims out of Chinese people with a “revolutionary ideology.” Another, more recent historical interpretation suggests the film could be seen as an operatic historical tragedy informed by the trauma and grief of the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. After all, Chen and other Fifth Generation filmmakers learned how to use double-meanings (allegories, symbols, and visual metaphors) to make a decidedly political critique that often meant their films landed in the censors’ hands. Take how Zhang Yimou infused an equal balance of performance and political commentary in To Live (1994), a film that spans roughly the same timeline as Farewell My Concubine and also stars Gong Li, except it follows a shadow puppet performer instead of an actor in the Peking opera. But much like Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, Chen’s film is more concerned with a study of its central character than an accurate portrayal of Chinese history. Lean’s film, too, journeys across history without stopping for a thorough analysis of every political and social development. Instead, Chen, Zhang, and Lean’s respective films each use their gorgeous visual staging of historical events, spectacular production value, and exquisite photography in a symbolic manner that elevates the personal relationships on display.

In Chen’s remarks to Western journalists around Farewell My Concubine’s release, the director fuels the association between his film and Lean-style epics. Larson notes that he draws from his personal experiences during the Cultural Revolution, using the film to explore his anger about feeling “duped” by the Chinese state, which made victims out of Chinese people with a “revolutionary ideology.” Another, more recent historical interpretation suggests the film could be seen as an operatic historical tragedy informed by the trauma and grief of the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. After all, Chen and other Fifth Generation filmmakers learned how to use double-meanings (allegories, symbols, and visual metaphors) to make a decidedly political critique that often meant their films landed in the censors’ hands. Take how Zhang Yimou infused an equal balance of performance and political commentary in To Live (1994), a film that spans roughly the same timeline as Farewell My Concubine and also stars Gong Li, except it follows a shadow puppet performer instead of an actor in the Peking opera. But much like Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, Chen’s film is more concerned with a study of its central character than an accurate portrayal of Chinese history. Lean’s film, too, journeys across history without stopping for a thorough analysis of every political and social development. Instead, Chen, Zhang, and Lean’s respective films each use their gorgeous visual staging of historical events, spectacular production value, and exquisite photography in a symbolic manner that elevates the personal relationships on display.

Farewell My Concubine is not only Chen’s most celebrated picture to date but one of Chinese cinema’s most widely acclaimed pictures among global audiences. The film defied its controversy—broaching taboo subject matter such as child abuse, political critique, queerness, opium addiction, prostitution, and suicide—to find a unique status in Chinese and international cinema. For some, the film remains inseparable from Leslie Cheung, whose celebrity and sudden death echo the life of Cheng Dieyi. “Leslie Cheung is Cheng Dieyi,” wrote the film’s director not long after Cheung’s suicide. For others, it is a stunning visual presentation infused with an ancient form of art defined by specific cultural, historical, and aesthetic traditions—all, rendered in sublime images of ornamented stage performances and grim political upheaval with alternating beauty and immediacy. Farewell My Concubine is also a harrowing character study that ends in theatrical tragedy, which follows how China’s volatile changes over the last century impacted the bodies and minds of its people. Finally, of course, the film is all of these things and more. Thoughtfully considered and gorgeously rendered in a production worthy of Lean, Chen’s film marks the intersection of life and art, politics and performance, the intimate and the epic.

Bibliography:

Chiao, Peggy, and Lawrence Chua. “Chen Kaige.” BOMB, 1 October 1993. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/chen-kaige/. Accessed 1 April 2022.

Cornelius, Sheila, with Ian Haydn Smith. New Chinese Cinema: Challenging Representations. Wallflower Press, 2002.

Dolby, William. Eight Chinese Plays from the Thirteenth Century to the Present. Columbia University Press, 1978.

Havis, Richard James, and Chen Kaige. “Changing the Face of Chinese Cinema: An Interview with Chen Kaige.” Cinéaste, vol. 29, no. 1, 2003, pp. 8–11, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41689663. Accessed 4 April 2022.

Hui, Luo. “Theatricality and Cultural Critique in Chinese Cinema.” Asian Theatre Journal, vol. 25, no. 1, 2008, pp. 122–37, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27568438. Accessed 2 April 2022.

James, Caryn. “Film View; You Are What You Wear.” The New York Times, 10 October 1993. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/10/movies/film-view-you-are-what-you-wear.html/. Accessed 1 April 2022.

Kaplan, E. Ann. “Reading Formations and Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine.” Transnational Chinese Cinemas: Identity, Nationhood, Gender. Sheldon Hsiao-peng Lu, editor. University of Hawai’i Press, 1997, pp. 265-275.

Kristof, Nicholas D. “China Bans One of Its Own Films; Cannes Festival Gave It Top Prize.” The New York Times. 4 August 1993. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/04/movies/china-bans-one-of-its-own-films-cannes-festival-gave-it-top-prize.html. Accessed 4 April 2022.

Larson, Wendy. “The Concubine and the Figure of History: Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine.” Transnational Chinese Cinemas: Identity, Nationhood, Gender. Sheldon Hsiao-peng Lu, editor. University of Hawai’i Press, 1997, pp. 331-346.

Leung, Helen Hok-Sze. Farewell My Concubine: A Queer Film Classic. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2010

Tyler, Patrick E. “China’s Censors Issue a Warning”. The New York Times. 4 September 1993. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/09/04/movies/china-s-censors-issue-a-warning.html. Accessed 4 April 2022.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review