The Definitives

Fanny and Alexander

Essay by Brian Eggert |

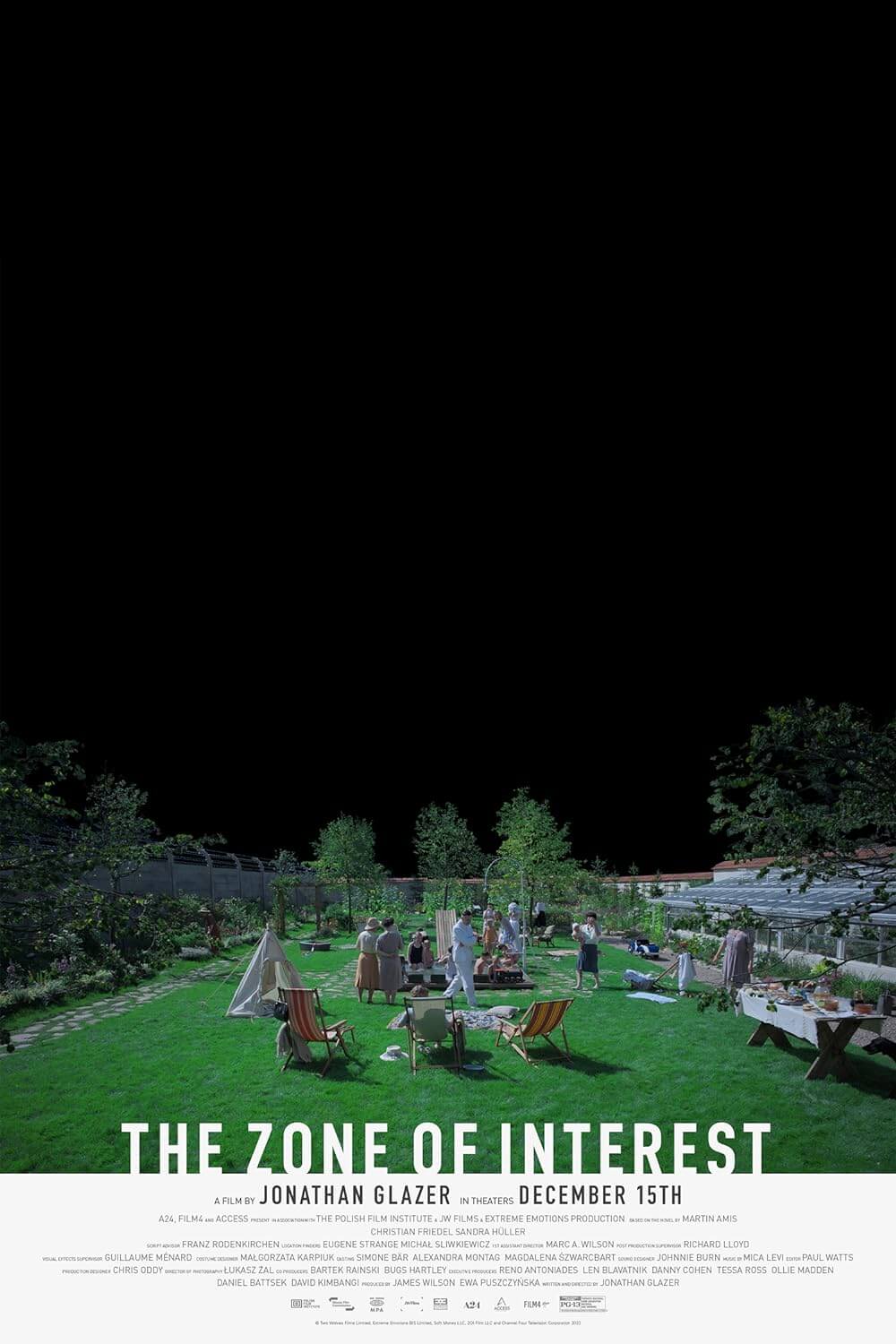

Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander regards family through the curious, innocent eyes of a child, observing its illusions and relating its painful truths. The filmmaker equates family and adulthood to a theatrical stage, peering behind the curtain to expose the foundations and guises behind their presentation. Told from the dreamlike perspective of youth, Bergman’s film reflects on how family and the changing seasons thereof shift into a sweeping, supremely theatrical tale of drama and fantasy, and through that outlines from his own experiences the origin of his desire for storytelling. Amassing his life’s obsessions into a singular tome, albeit unconsciously, Bergman both encompasses and transcends them completely. Believed to be made from some autobiographical influence, Fanny and Alexander bears undeniable associations to the director’s personal life, though he has argued otherwise. Having composed the script over a number of years, Bergman began by writing about the bourgeois home of his grandmother and its active surroundings in Uppsala, in time pouring both fictional and personal influence into the work. And yet, the result is stylistically distant from the pensive, decisively Nordic creations to which Bergman remains associated, such as The Seventh Seal or Wild Stawberries. The film contains no long ruminations about the nature of God or the absurdity of romantic love. His dialogue remains dramatic but not overly poetic. His tone carries ethereal strokes without making his canvas an overt work of symbolism. These notable differences from Bergman’s usual output suggest a personal, even jealous devotion to Fanny and Alexander that when placed alongside events from his personal life, the similarities cannot be denied.

Production began in September of 1981, eventually costing some $6 million and involving more than a thousand extras. It was Bergman’s biggest, most expensive film to date. The Swedish Film Institute, combined with the French production company Gaumont and West German television, floated the bill. The shoot lasted six months, and when he completed his work, Bergman announced it would be his last Swedish film. Released in Sweden as a television broadcast in five parts, and then internationally in a 188-minute theatrical cut, Fanny and Alexander was gloriously received and earned much attention on the world cinema awards circuit, though it pained Bergman to cut two hours from his saga. Among the notices, the film won four Academy Awards (including Best Foreign Film, Cinematography, Art Direction, and Costume Design) and was nominated for another two (Bergman for Direction and Original Screenplay). Film scholars and historians have continued their praise through the years, elevating the picture into one of the most cherished ever made. Lasting five hours in its complete form, the film’s narrative breadth eases into a comforting familial womb made of strong bonds between the audience and Bergman’s family subject. Viewership becomes remarkably involving, as characters described with precise emotional resonance seem to grow flesh and come alive. Meanwhile, the unrestrained length of the picture allows the experience to fully engulf its viewers, leaving them no choice but to commit fully to Bergman’s world.

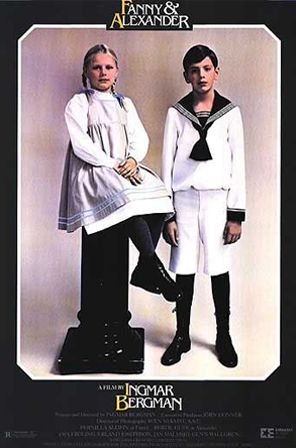

What remains fascinating is how effortlessly the time passes, turning an otherwise lengthy screening of Fanny and Alexander into an experience that breezes by, in the same way that hours disappear in stimulating conversation with family and friends. In 1907 Uppsala, the bourgeois Ekdahls operate the local theater. Materfamilias Helena (Gunn Wållgren) allows her eldest of three sons Oscar Ekdahl (Allan Edwall) to manage the family business. After Oscar dies of a stroke while rehearsing, his wife Emilie (Ewa Fröling) feels she must move on. The family loses grasp of its unity. Emilie remarries, somehow charmed by the local bishop Edvard Vergerus (Jan Malmsjö), whose godliness she believes will help her children, Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and Alexander (Bertil Guve), the latter of whom has been seeing the ghost of his father. Suffering the Bishop’s cruel dogmatism, the children endure beatings and dour living conditions in the name of the Bishop’s piety, until they are smuggled from his rule by merchant and family friend Isak Jacobi (Erland Josephson). Emilie, meanwhile, escapes her cruel husband by slipping him a sedative, and conveniently, unable to wake, the bishop is burned alive the same night in a fortuitous fire. And though the Ekdahls come together once again, Alexander finds himself haunted by the ghosts of his experience, his family turmoil and the Bishop exacting a permanent imprint.

What remains fascinating is how effortlessly the time passes, turning an otherwise lengthy screening of Fanny and Alexander into an experience that breezes by, in the same way that hours disappear in stimulating conversation with family and friends. In 1907 Uppsala, the bourgeois Ekdahls operate the local theater. Materfamilias Helena (Gunn Wållgren) allows her eldest of three sons Oscar Ekdahl (Allan Edwall) to manage the family business. After Oscar dies of a stroke while rehearsing, his wife Emilie (Ewa Fröling) feels she must move on. The family loses grasp of its unity. Emilie remarries, somehow charmed by the local bishop Edvard Vergerus (Jan Malmsjö), whose godliness she believes will help her children, Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and Alexander (Bertil Guve), the latter of whom has been seeing the ghost of his father. Suffering the Bishop’s cruel dogmatism, the children endure beatings and dour living conditions in the name of the Bishop’s piety, until they are smuggled from his rule by merchant and family friend Isak Jacobi (Erland Josephson). Emilie, meanwhile, escapes her cruel husband by slipping him a sedative, and conveniently, unable to wake, the bishop is burned alive the same night in a fortuitous fire. And though the Ekdahls come together once again, Alexander finds himself haunted by the ghosts of his experience, his family turmoil and the Bishop exacting a permanent imprint.

The prologue scenes show ten-year-old Alexander as he examines a toy theater, above which reads the notice “not for pleasure alone”. Bergman determines that families base their composure on false fronts no more real than the reaches of the stage, or Alexander’s fantastical imagination. Exposing the miniature façade to understand how it works, in his curious innocence, Alexander does not quite grasp the metaphoric range of his discoveries, at least not yet. He continues to wander about his grandmother’s empty home before guests arrive for the Christmas party, allowing his imagination to take over and pass time. He sees a nude female sculpture come alive and motion for him to come nearer; hiding under a table, Alexander remains frozen in his spot, as he also sees Death lingering in the room. The two images contrast to present an emblematic outline for the coming events in the film, determining that every joy is balanced by hardship.

Followed by an extended sequence of Christmas celebrations with the Ekdahls, the prologue distinguishes the successive events as the surface from which the remainder of the film slowly chips away. A lush, sumptuous feast ensues, a panorama of joyous family conversation and interactions throughout the thriving household—sights inspired by Swedish painter Carl Larsson. Uncle Gustaf-Adolf (Jarl Kulle) warns the help that the theater staff is a mixed lot but do not deserve raised eyebrows or upturned noses, and then the jubilation begins. Indeed, Bergman’s film stimulates the senses, immersing us in an occasion filled with mouth-watering food, bright Christmas colors, flirtations abound, cheerful songs, deep reds matched in their lushness only by Jan Van Eyck, a flatulence fireworks show by Uncle Carl (Börje Ahlstedt), staid bible reading, a feathery pillow fight, and after the other children are put to bed, Alexander remains awake, overhearing the adults’ solemn songs, blithe infidelities, and dramatic recitations. These are some of the most joyous details ever captured on film, and longtime cinematographer and Bergman collaborator Sven Nykvist lends the picture incomparable beauty.

Followed by an extended sequence of Christmas celebrations with the Ekdahls, the prologue distinguishes the successive events as the surface from which the remainder of the film slowly chips away. A lush, sumptuous feast ensues, a panorama of joyous family conversation and interactions throughout the thriving household—sights inspired by Swedish painter Carl Larsson. Uncle Gustaf-Adolf (Jarl Kulle) warns the help that the theater staff is a mixed lot but do not deserve raised eyebrows or upturned noses, and then the jubilation begins. Indeed, Bergman’s film stimulates the senses, immersing us in an occasion filled with mouth-watering food, bright Christmas colors, flirtations abound, cheerful songs, deep reds matched in their lushness only by Jan Van Eyck, a flatulence fireworks show by Uncle Carl (Börje Ahlstedt), staid bible reading, a feathery pillow fight, and after the other children are put to bed, Alexander remains awake, overhearing the adults’ solemn songs, blithe infidelities, and dramatic recitations. These are some of the most joyous details ever captured on film, and longtime cinematographer and Bergman collaborator Sven Nykvist lends the picture incomparable beauty.

The family of theatrical performers maintains their act through celebration, and only when Oscar dies does this façade crumble. While rehearsing a production of Hamlet, wherein, appropriately, Oscar plays the ghost, Alexander sees his father collapse on stage. Perhaps, through some sophisticated understanding and detachment toward death, Alexander never stops seeing his father as a character in a play, as if his death scene was merely an act, which allows him to see his father as a ghost throughout the picture. Or perhaps his father’s good-night words in the late Christmas hours, “Nothing separates me from you all,” linger with the child and create a ghostly projection. But Bergman allows other characters, like Helena, to see Oscar’s ghost as well. And later in the film, Alexander finds himself haunted by ghosts of the Bishop’s former daughters. These apparitions are not something from Alexander’s imagination, rather a reality of Bergman’s world.

Upon Oscar’s death, an eerie atmosphere takes over Fanny and Alexander; the film seems to enter a nightmarish dream best punctuated by sound. Bergman admits to having audio sensitivities adopted from his father, and the director was known to make very quiet films—perhaps this is why. To be sure, Bergman’s lack of background music and general silence makes the scene featuring Emilie’s deathly screams as she cries out for the loss of her husband all the more jarring on an auditory level, but also on a level of pure emotion linking to the senses. And then there are audio patterns, such as the film’s brief stops to dwell on a ticking clock or the spare use of music. Never has Chopin’s Death March been so effectively utilized than in Oscar’s funeral scene, using the irony now associated with the music to underline Alexander’s tirade of swears at the procession. Fanny and Alexander uses sound and the contrasting lack thereof more than any other Bergman film, subjecting the audience to constant bombardment ranging from laughter to merry songs to crying to violent silence.

Upon Oscar’s death, an eerie atmosphere takes over Fanny and Alexander; the film seems to enter a nightmarish dream best punctuated by sound. Bergman admits to having audio sensitivities adopted from his father, and the director was known to make very quiet films—perhaps this is why. To be sure, Bergman’s lack of background music and general silence makes the scene featuring Emilie’s deathly screams as she cries out for the loss of her husband all the more jarring on an auditory level, but also on a level of pure emotion linking to the senses. And then there are audio patterns, such as the film’s brief stops to dwell on a ticking clock or the spare use of music. Never has Chopin’s Death March been so effectively utilized than in Oscar’s funeral scene, using the irony now associated with the music to underline Alexander’s tirade of swears at the procession. Fanny and Alexander uses sound and the contrasting lack thereof more than any other Bergman film, subjecting the audience to constant bombardment ranging from laughter to merry songs to crying to violent silence.

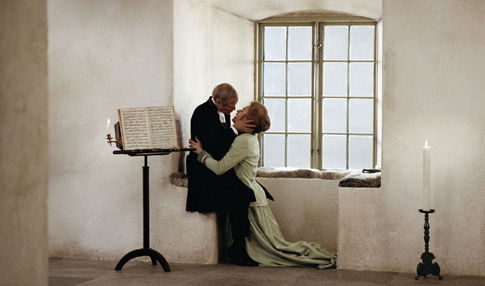

Described by Bergman as “God’s Silence,” when the children and their mother come under the rule of the Bishop, he uses soundlessness as a measure for holiness. The film’s tone changes from saddening to terrifying, as the festive boom of the Ekdahls gives way for a frighteningly calm “atmosphere of purity and austerity.” A year has passed and Emilie seeks to escape the world that reminds her of her mourning; she marries the Bishop, who despite asking her to leave not only her possessions but “friends, habits, and thoughts” behind, creates a false stability for her. She looks for certainty, something to distance herself from the comparative artistic uncertainty contained in the memory of Oscar, thus distancing herself from pain. “Through you, I’ll come to know God’s true nature,” she tells the Bishop, as if her new marriage is the antidote for not understanding God’s intention behind Oscar’s death. Meanwhile, Oscar’s ghost watches over the wedding; Alexander sees him and leaves the room in a rage.

Transported to the Bishop’s uniform home of white surfaces and quiet rooms, Emilie loses control of her children to her new husband. The Bishop’s crooked sister and attendants dote on him. Blank walls leave no room for imagination. The sick, bloated, pale aunt rests like Death waiting in the corner of the room, watching the new family eat. Alexander images the whole scenario is Hamlet and attempts to defy his villainous stepfather like the hero of a play. However strong the canings and cruel the punishments, the boy remains defiant; Fanny and Alexander even pray for the Bishop’s death. Through an impossible moment of enchantment conducted by the Jewish merchant Isak, the Bishop loses the children, and only releases Emilie after being drugged and abandoned. He dies when Alexander wills it, returning the Ekdahls into a state of togetherness, delight and fancy returned—all events that occur under impossible, magical circumstances. Even still, in the final moments, Alexander comes to be pushed down, the Bishop’s phantom standing above him reveling, “You can’t escape me.”

Transported to the Bishop’s uniform home of white surfaces and quiet rooms, Emilie loses control of her children to her new husband. The Bishop’s crooked sister and attendants dote on him. Blank walls leave no room for imagination. The sick, bloated, pale aunt rests like Death waiting in the corner of the room, watching the new family eat. Alexander images the whole scenario is Hamlet and attempts to defy his villainous stepfather like the hero of a play. However strong the canings and cruel the punishments, the boy remains defiant; Fanny and Alexander even pray for the Bishop’s death. Through an impossible moment of enchantment conducted by the Jewish merchant Isak, the Bishop loses the children, and only releases Emilie after being drugged and abandoned. He dies when Alexander wills it, returning the Ekdahls into a state of togetherness, delight and fancy returned—all events that occur under impossible, magical circumstances. Even still, in the final moments, Alexander comes to be pushed down, the Bishop’s phantom standing above him reveling, “You can’t escape me.”

Bergman blurs the realms of reality and fantasy, acknowledging that no matter how great the escape, reality always resurfaces behind it, even so far as to terrorize fantasy. This interplay applies to both families and art. For Isak’s nephew, the magician and puppetmaster Aron (Mats Bergman), God is little more than one of his marionettes, at one moment looming in his awful white-bearded form over Alexander, the next nothing more than some wood and strings. For Bergman, reality’s horrible truths must be represented in imaginative terms to divert and mirror, entertain and inform, provide escape and send the audience deeper into understanding of how the world works. This theme is best described by Oscar, when he makes a final speech to his theater staff on Christmas night about the significance of their artform: “Outside is the big world, and sometimes the little world succeeds in reflecting the big one so that we understand it better. Or perhaps, we give the people who come here a chance to forget for a while, for a few short moments, the harsh world outside.” The Ekdahl family exists on a stage, where scrutinized it must perform; only in maintaining those illusions can a family survive cheerfully. That they are a family grounded by theater, and that Alexander cannot differentiate between actuality and his dreams, underscores this thesis. In comparing a contented family to an artistic performance, Bergman reveals his own vision and mistrust of family, driving the autobiographical discussions following the film’s release. Much can be said for how Bergman himself escaped his family to delve into his art, wherein reality is managed and reconfigured to his liking in the form of theater and cinema.

Ingmar Bergman was born in Uppsala in 1918. Raised under the strict tutelage of his chaplain father; his ancestors were mostly farmers and pastors, passing down traditionalist godliness and staunch theological groundwork from which he could draw later inspiration and rebel from. His parents were quietly and palpably at war, his mother Karin a repressed female spirit and his father Erik a rigid clergyman. Their discussions were muted and polite. Daily life was orderly. “That strict middle-class home gave me a wall to pound on, something to sharpen myself against,” Bergman remembered. Punishments came with objective emotional distance, like a necessary duty that must be carried out by a steadfast father. The director would dwell on this in his later films, such as Fanny and Alexander, where villains or emotionally distant parental figures distribute punishment without the slightest perception of the scarring effect their actions have. Bergman’s biographers construe too much from the supposed defining conflict between father and son; the two shared opposing views in relation to their “duty to God” to be sure, but his father should not be painted the antagonist of his son’s life story. Rather, young Bergman saw the strict religious household as a prison to which most subjects in his films were sentenced, complete with questions of faith and family forced out by such surroundings. “God’s Silence” filled his childhood home, with punishments more often being the silent treatment over a physical beating. Not until his father slapped him for leaving college did Bergman’s relationship with his parents become openly rebellious, inspiring his subsequent bohemian lifestyle and pursuit of the arts, most fervently film. Bergman’s domineering father served merely as a human springboard, sending the director into a much larger culvert riddled by religion-inspired cruelty and unfeeling behavior that saturated his imagination.

Ingmar Bergman was born in Uppsala in 1918. Raised under the strict tutelage of his chaplain father; his ancestors were mostly farmers and pastors, passing down traditionalist godliness and staunch theological groundwork from which he could draw later inspiration and rebel from. His parents were quietly and palpably at war, his mother Karin a repressed female spirit and his father Erik a rigid clergyman. Their discussions were muted and polite. Daily life was orderly. “That strict middle-class home gave me a wall to pound on, something to sharpen myself against,” Bergman remembered. Punishments came with objective emotional distance, like a necessary duty that must be carried out by a steadfast father. The director would dwell on this in his later films, such as Fanny and Alexander, where villains or emotionally distant parental figures distribute punishment without the slightest perception of the scarring effect their actions have. Bergman’s biographers construe too much from the supposed defining conflict between father and son; the two shared opposing views in relation to their “duty to God” to be sure, but his father should not be painted the antagonist of his son’s life story. Rather, young Bergman saw the strict religious household as a prison to which most subjects in his films were sentenced, complete with questions of faith and family forced out by such surroundings. “God’s Silence” filled his childhood home, with punishments more often being the silent treatment over a physical beating. Not until his father slapped him for leaving college did Bergman’s relationship with his parents become openly rebellious, inspiring his subsequent bohemian lifestyle and pursuit of the arts, most fervently film. Bergman’s domineering father served merely as a human springboard, sending the director into a much larger culvert riddled by religion-inspired cruelty and unfeeling behavior that saturated his imagination.

Bergman relished time at his grandmother’s richly decorated apartment located on Trädgårdsgatan in Uppsala, center to some of the region’s most atrocious medieval horrors. Macabre tales of sacrifices and executions filled the histories of every building or square, mapping his thoughts with the underpinnings of medieval drama. Religious iconography and temperaments surrounded him there; sculptures and paintings of a grief-stricken world filled with all the death and lamentation offered by Christianity, in particular Swedish Lutheranism—one image on a local church’s ceiling featured a knight playing chess with Death, inspiring The Seventh Seal. Images of ancient beauty were otherwise surrounded by a grim territory, the religious doom and gloom of medieval origins. But inside his grandmother’s home a world of extravagant ornamentation emerged, radical and escapist when compared to the home of Bergman’s parents, and surely the inspiration for Alexander’s experiences in Helena’s home—perhaps Bergman too saw ghosts and watched sculptures come alive.

Despite growing up in poverty-ridden times in Sweden, young Ingmar still attended The Slotts Cinema with his grandmother. Screenings of Charles Chaplin’s The Pawnshop and D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation foundationalized his understanding of the artform. When the price of a ticket went up beyond his allowance, his father’s loose change made up the difference. He became an avid film buff, his favorites being Universal Studios horror pictures like 1931’s Frankenstein. In Fanny and Alexander, when the young boy comes face-to-face with the statue of a breathing, luminous mummy in Isak’s home, Nykvist’s lighting evokes Boris Karloff’s eerie performance in Universal’s The Mummy from 1932, perhaps recreating a childhood terror of young Bergman’s. In trade for his collection of tin soldiers, Bergman received from his brother a “magic lantern” and projected brief moving pictures at home. Just as Alexander dissected the illusions of family by studying the puppet theater, the light of Bergman’s imagination, of his desire to dramatize human complexity, flickered on his wall.

Despite growing up in poverty-ridden times in Sweden, young Ingmar still attended The Slotts Cinema with his grandmother. Screenings of Charles Chaplin’s The Pawnshop and D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation foundationalized his understanding of the artform. When the price of a ticket went up beyond his allowance, his father’s loose change made up the difference. He became an avid film buff, his favorites being Universal Studios horror pictures like 1931’s Frankenstein. In Fanny and Alexander, when the young boy comes face-to-face with the statue of a breathing, luminous mummy in Isak’s home, Nykvist’s lighting evokes Boris Karloff’s eerie performance in Universal’s The Mummy from 1932, perhaps recreating a childhood terror of young Bergman’s. In trade for his collection of tin soldiers, Bergman received from his brother a “magic lantern” and projected brief moving pictures at home. Just as Alexander dissected the illusions of family by studying the puppet theater, the light of Bergman’s imagination, of his desire to dramatize human complexity, flickered on his wall.

The similarities between Bergman’s life and the film could go on and on, though he denied any implication that the film is wholly autobiographical, despite the obvious comparison of himself to Alexander and the Bishop to Bergman’s father. He said while still in production, “It’s not so much a chronicle as a Gobelin tapestry, from which you can pick the images and the incidents and the characters that fascinate you.” One cannot deny the projected comparisons, as Bergman himself rebelled against his own dictatorial, religious father figure to find himself emerging from the conflict an adult, just like Alexander. Of his family, perhaps it can be said that long ago Bergman lifted the curtain on them, which every child does to their parents at some point, destroying life’s naïve first impressions to reveal the sad truths and deep-rooted flaws of loved ones, and in the end, he became a better artist for it.

Bergman once suggested that the theater served him as a faithful wife, whereas cinema provided a mistress with which he could experiment. Strange how he marries the two with Fanny and Alexander, and even finds a polygamist’s balance. Absorbing his audience into a place between reality and dreams, Bergman chronicles his life’s work in a motion picture both characteristically Bergmanesque and yet unlike anything he accomplished before or after its release. Bergman called the film “the sum total of my life as a filmmaker,” and therein affirmed how his film’s scope reaches beyond merely family or the importance of the cinema and theater. Rather, it provides a singular expression encompassing an entire career of astute observations and lyrical rumination, profound drama through pensive thought, and how Bergman beautifully weighs life’s questions against its joys and sorrows.

Bibliography:

Bergman, Ingmar. Images: My Life In Film. Foreword by Woody Allen. Arcade Publishing, 1995.

Bergman, Ingmar; Tate, Joan. The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography. University Of Chicago Press, 2007.

Cowie, Peter. Ingmar Bergman: A Critical Biography. New York: Scribner, c1982.

Singer, Irving. Ingmar Bergman, Cinematic Philosopher: Reflections on His Creativity. The MIT Press, 2007.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review