The Definitives

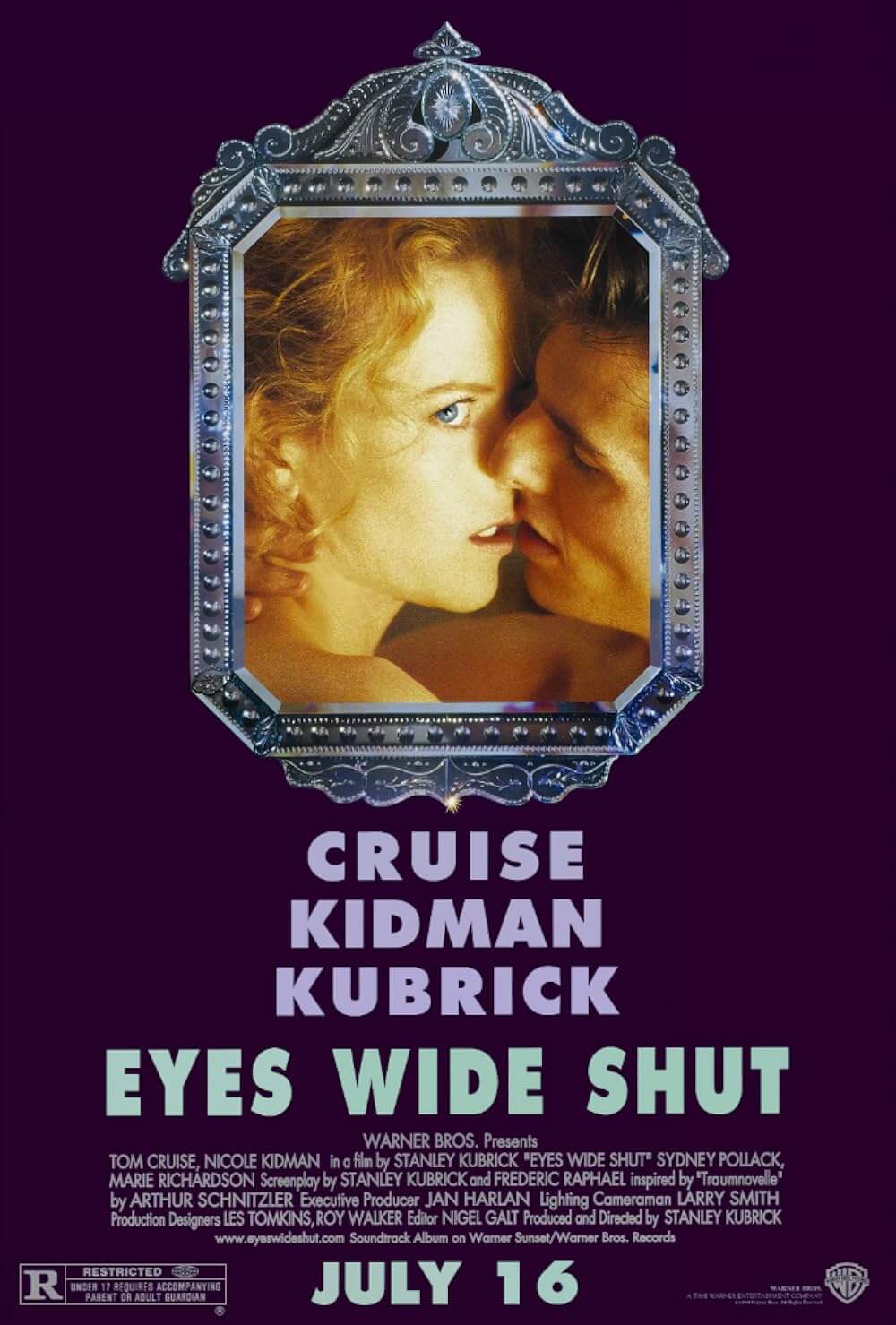

Eyes Wide Shut

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Editor’s Note: This essay was originally published on July 12, 2011. It has been edited and expanded.

Stanley Kubrick spent most of his filmmaking career thinking about how to bring Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella Traumnovelle (Dream Story) to the screen. He deliberated over its dreamlike structure and how to capture the Austrian writer’s text on film. While mulling over the project, he incorporated aspects of its themes and meanings into his other films. And after every completed project, he would consider whether the time was right to finally adapt Traumnovelle. When he eventually made Eyes Wide Shut in 1999, it confounded most moviegoers and critics. Yet, the film secured a place in the unconscious and fostered a lingering fascination for many, often followed by repeat viewings, new assessments, and reconsiderations in the years to come. This was often the pattern with the director’s work, but it was more pronounced with his final film, partly because of its lengthy road to completion. Kubrick had spent years developing a script and making characteristically scrupulous preproduction plans. The eventual shoot became the longest in filmmaking history, amounting to 18 months of exhausting effort, followed by an intense editing process, at the end of which the 70-year-old director died of heart failure. Eyes Wide Shut would amount to a culmination of his lifelong obsessions—his most psychologically complex, formally demanding, and enigmatic piece of filmmaking.

The full 5,400-word essay is currently posted on Patreon. To read it, you can purchase access individually. You can also join Deep Focus Review’s Patron community, where you’ll first receive exclusive access to this essay and many other reviews and blogs published on Patreon.

Patrons also get access to:

• Exclusive weekly blog posts

• Streaming recommendations every Friday

• Polls to pick the movies reviewed on Deep Focus Review and Patreon

• Access to the open AMA and DFR Community

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review