The Definitives

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Editor’s Note: This essay was originally published on July 12, 2011. It has been edited and expanded.

Stanley Kubrick spent most of his filmmaking career thinking about how to bring Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella Traumnovelle (Dream Story) to the screen. He deliberated over its dreamlike structure and how to capture the Austrian writer’s text on film. While mulling over the project, he incorporated aspects of its themes and meanings into his other films. And after every completed project, he would consider whether the time was right to finally adapt Traumnovelle. When he eventually made Eyes Wide Shut in 1999, it confounded most moviegoers and critics. Yet, the film secured a place in the unconscious and fostered a lingering fascination for many, often followed by repeat viewings, new assessments, and reconsiderations in the years to come. This was often the pattern with the director’s work, but it was more pronounced with his final film, partly because of its lengthy road to completion. Kubrick had spent years developing a script and making characteristically scrupulous preproduction plans. The eventual shoot became the longest in filmmaking history, amounting to 18 months of exhausting effort, followed by an intense editing process, at the end of which the 70-year-old director died of heart failure. Eyes Wide Shut would amount to a culmination of his lifelong obsessions—his most psychologically complex, formally demanding, and enigmatic piece of filmmaking.

The seed of Eyes Wide Shut began, of course, when Kubrick read Schnitzler’s novella. The text follows Fridolin and Albertine, a Jewish couple in turn-of-the-century Vienna, whose sexual fantasies and jealousy nearly tear them apart. After a Carnival ball, Albertine confesses to having had a lurid fantasy about another man during their recent vacation. In a jealous response, Fridolin sets out on an increasingly dangerous nocturnal odyssey of sexually charged yet decidedly surreal encounters. They culminate with his intrusion into a masked orgy held by an elite secret society that issues a grave warning should he ever reveal what he saw. Whether Fridolin’s sexual adventures are real or merely dreamt remains unclear, but he returns home and confesses what happened to Albertine. The couple finds strength in their new appreciation for the difference between dreams and waking life—and their intersection in fantasies. Serialized in the magazine Die Dame before its publication in book form, Schnitzler’s text was translated into English by Otto P. Schinnerer, titled Rhapsody: A Dream Novel.

Accounts vary over when Kubrick first read the Schinnerer translation of Traumnovelle. One more frequently circulated story suggests that a shrink gave Kurbrick the book when he was shooting Spartacus (1960). However, the director’s early producing partner, James B. Harris, claims Kubrick had read Schnitzler before they first met in 1955. Whether his access to Traumnovelle came from his father’s extensive library, his time at New York’s City College and Columbia University, or his first wife, Ruth Sobotka, who was interested in Austrian literature, no one can confirm with certainty. Most recent scholarship, including the extensive work by authors Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams in Eyes Wide Shut: Stanley Kubrick and the Making of His Final Film (2019) and Kubrick: An Odyssey (2024), resolve that the director had discovered Schnitzler in the 1950s or earlier. What’s not disputed is that Kubrick nursed lifelong neuroses around jealousy and sex, and Schnitzler’s considerable sex life and fixation on sexuality, introspection, adultery, and seduction emerged in his work. During Kubrick’s first marriage, for instance, he resented his wife’s advanced sexuality. He was jealous, and the notion that a spouse could look at their partner and conceal desire or even an affair horrified him. At the same time, he fantasized about other women yet felt helpless to act, much like Fridolin and the protagonist in Eyes Wide Shut.

Early in his career, Kubrick compiled ideas and started developing several inward-looking scripts about marriage, sex, and infidelity to confront his fixations, including screenplays called Jealousy, The Married Man, and A Perfect Marriage. None of them materialized, but given his preoccupations, it’s easy to understand what compelled him to adapt Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita in 1962. Still, Schnitzler was always on his mind, but he could not ignore the challenges of adapting Traumnovelle. In a 1960 interview with The Observer, he made a vague allusion to making a film that sounds like Schnitzler’s work and conveys “the times, psychologically, sexually, politically, personally.” He added, “It’s probably going to be the hardest film to make.” His collaborator and second wife, Christiane Kubrick, also discouraged him from tackling Traumnovelle too early, realizing that the subject would undoubtedly strain their marriage, which was still in its early years after they wed in 1958. Christiane later told critic Richard Schickel that they had numerous arguments about him adapting the Schnitzler story over the years, and her husband took them “as evidence that material so stirring must be worth doing.”

By the mid-1990s, when the director finally started work on his Schnitzler film in earnest, Kubrick’s adaptation had undergone several false starts. Over the decades, Kubrick met with writers such as Anthony Burgess, John le Carré, Michael Herr, Diane Johnson, and Terry Southern to work out the screenplay. Warner Bros. even announced the project in 1971, when Kubrick had imagined his version of Traumnovelle as a black-and-white sex comedy starring Woody Allen, whose early, funny films the director loved. Then he shifted to Steve Martin, meeting with the comedian from one of his favorite films, The Jerk (1979), to discuss the project. Eventually, he changed his mind and started to explore a more mysterious experience bordering on a thriller, perhaps because Albert Brooks so effectively captured jealousy in his comedy Modern Romance (1981). Brooks plays a film editor who keeps breaking up with his girlfriend because of an irrational, paranoid jealousy, stemming from his own sense of inadequacy. Famously, Kubrick called Brooks to congratulate him on the film and ask him how he conveyed jealousy so well. Transitioning to a serious tone for his adaptation of Traumnovelle, Kubrick wanted the leads to be played by a real-life celebrity couple. He didn’t want the neuroses in the story to be attributed to ethnicity, making the main character’s preoccupations those of a neurotic or Jewish stereotype. By contrast, having an attractive couple—such as Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger or Bruce Willis and Demi Moore—at the center suggested these problems had more to do with universal emotional concerns that no degree of good looks or success could prevent.

This long-tailed development process was nothing new for the filmmaker. Every Kubrick production from the mid-1960s onward found the director committing years to exhaustive research, sometimes only to have the project fall through. The period between his last two films, Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut, represents his most extended break from actual production in his career. During that time, Kubrick vacillated between potential projects, accumulating vast libraries of research on a Holocaust film based on Louis Begley’s Wartime Lies, a Viking epic based on H. Rider Haggard’s Eric Brighteyes, what would eventually become A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), and others. But in 1997, Warner Bros. announced that production would finally get underway on a new Kubrick film, which he wrote alongside Frederic Raphael, the Oscar-winning screenwriter of Darling (1965) and Two for the Road (1967). Throughout the lengthy shoot, even the months immediately following his death, Kubrick’s usual reclusiveness and demand for secrecy during production escalated public curiosity. The facts remained scant. Besides announcing the project’s two leads, Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, outlets such as Entertainment Weekly peddled unconfirmed information about the plot, claiming the stars would play “married psychiatrists who become obsessed with two of their patients.”

Kubrick had been in contact with Cruise since the early 1990s about a collaboration. Since the couple’s marriage in 1990, Cruise and Kidman had been the subject of tabloid fodder, from baseless rumors about Cruise’s sexuality and the couple’s status as Scientologists. The former was in the prime of his career, having earned an Oscar nomination for Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and reigning as champion over the North American box office throughout the 1990s. After Kidman starred alongside Cruise in Days of Thunder (1990) and Far and Away (1992), the Aussie performer started to show her range in To Die For (1995) and several Hollywood blockbusters. However, neither of them had done anything like a Kubrick film before. Throughout the extended shoot, which kept the stars from making other projects for almost two years, the media fueled rumors that they were finding Kubrick impossible to work with after supporting actors Harvey Keitel and Jennifer Jason Leigh left the production, their roles filled by Sydney Pollack and Marie Richardson. Reshoots lengthened the actual filming to around 400 days, long for even Kubrick’s typically extended shoots, while post-production took another year.

All the while, reports of a protracted and troubled production failed to consider Kubrick’s usual painstaking methods, which had gone into overdrive from Kubrick’s decades-long interest in Schnitzler’s novella. His desire to get the story right, after it had consumed him for so many years, doubtlessly inflamed his already extreme meticulousness. In the years following Eye Wide Shut’s release, those involved in the production would tell stories about how Kubrick would demand countless takes, sometimes upward of 100, without offering clear direction. Perhaps he didn’t know what he was looking for until he saw it. Maybe the process broke down the pretenses of his actors, giving his signature detached quality to his performers. As usual, every detail had to be considered, labored over, and selected from thousands of options, evidenced in the endless boxes of photos in the Kubrick archive that informed his preproduction process. Kubrick encouraged Cruise and Kidman to go further than they ever had before to find their characters, from urging them to sleep in their apartment set to dominating their offscreen lives. For their part, the leads went along on the journey, receiving their director’s ideas with an open mind and trusting in his approach, no matter how unconventional or seemingly arbitrary.

This painstaking endeavor of making Eyes Wide Shut and the resultant expectations it fostered among moviegoers and critics led to another in a long line of Kubrick films that didn’t strike viewers with its full dimension until much later. Each of Kubrick’s projects, from Lolita to Full Metal Jacket, was misunderstood upon its initial release. Only after multiple viewings and a decade or so of consideration are his films declared masterful and placed among the most celebrated examples of cinematic art. Eyes Wide Shut is no exception; it might even be the most pronounced example of this phenomenon of latent appreciation. Upon its release, many of Kubrick’s devoted followers considered the film a disappointment or a dreary finale to a monumental career. It wasn’t until well into the twenty-first century that reassessments of what proves to be his most emotionally confronting picture became more widespread. Complex in structure, bold in subject matter, and, like most Kubrick films, subject to boundless readings and critical analyses, Eyes Wide Shut is one of Kubrick’s most obsessed-over pictures. And for good reason: The story is unusual and meandering; the presentation is among his most unorthodox. The experience might even be impenetrable, except when a viewer pierces its surface and looks deeper, the film supplies rich cinematic nourishment.

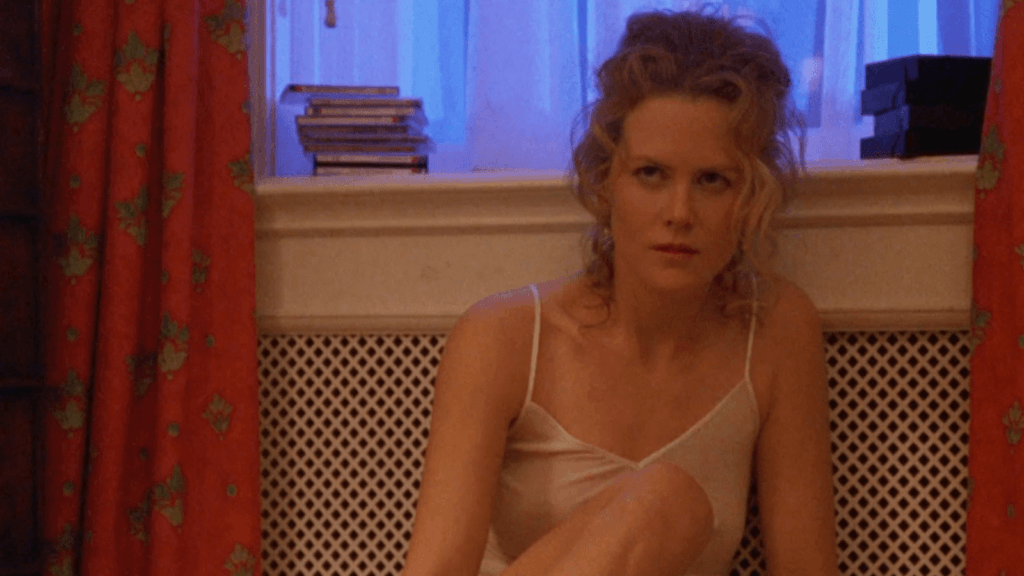

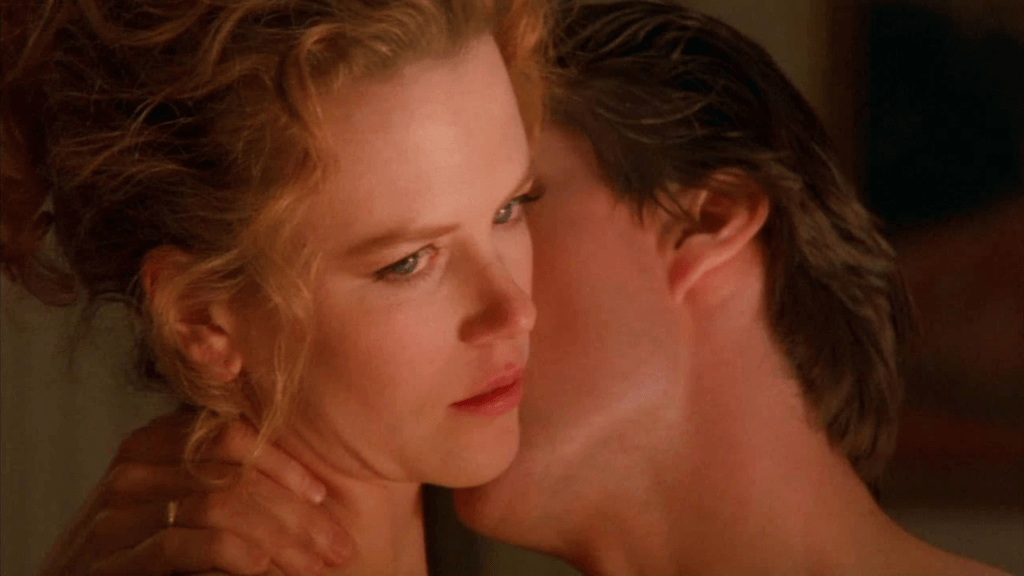

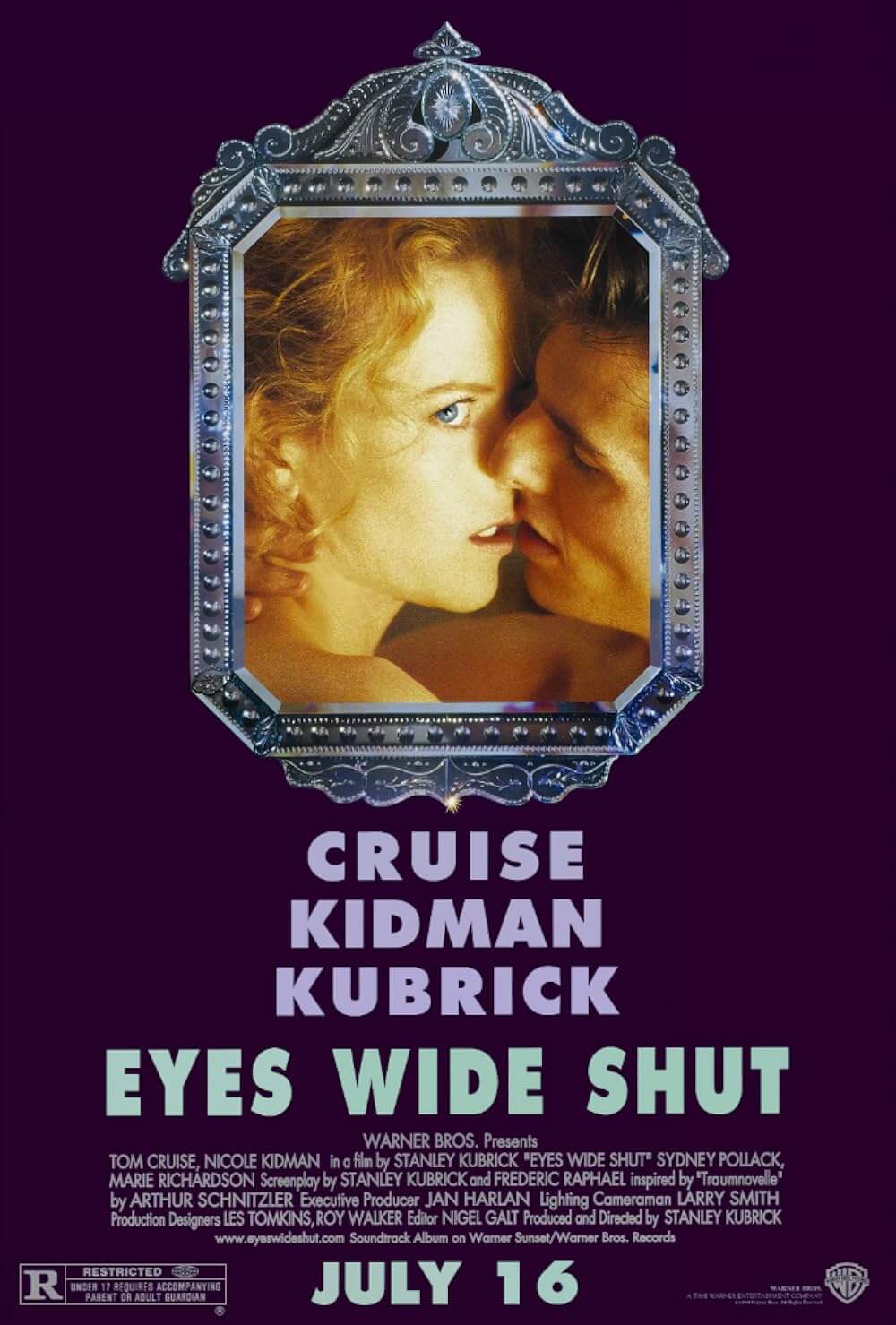

The film’s first image is brief and, at first, without context. Opening titles read Cruise, Kidman, and Kubrick’s names. Then, as if our eyes have opened for a momentary peep, the frame reveals a woman, Kidman, from behind. She loosens her dress and drops it to the floor, standing completely, unabashedly naked, as she lifts her feet out and kicks the dress aside. The screen turns black again and reveals the film’s title. In this single shot, the camera’s metaphorical lids open to the image and shut again, acting almost reflexively to expose us to temptation and then immediately take away its unapologetically voyeuristic male gaze. Holding on any longer would be self-indulgent and potentially dangerous. Such themes prevail throughout Eyes Wide Shut, whose very title indicates the waking dream state of a film lingering between reality and reverie. Kubrick may have derived the title from True Lies (1994), another film about jealousy and suspicion within a marriage. He even kept a copy of the screenplay in his office and invited James Cameron to his home to discuss how he made the Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jamie Lee Curtis actioner. As a title, Eyes Wide Shut has the same paradoxical structure as True Lies. Then again, as Kolker and Abrams observe, Kurbrick, who had approached John le Carré to write the script, may have borrowed the phrase from the author’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, where a character named Stanley enters a “honey pot” situation with “eyes wide shut.”

However the title formed—consciously or not—from other sources, Schnitzler’s novella remained a constant reference point and inspiration for the director. Kubrick takes us into the elegant Central Park West apartment of Dr. Bill Harford (Cruise) and his wife Alice Harford (Kidman), whose characters display marital intimacy, seemingly devoid of secrets—their openness apparent as Alice uses the toilet and Bill checks himself over in the bathroom mirror. Kubrick’s wide-angle lens portrays their impressive dwelling, decorated with paintings by Kubrick’s wife Christiane and her daughter Katharina Hobbs. The camera follows as these two well-dressed, attractive people leave their daughter with the babysitter so they may attend a high-class party on Fifth Avenue hosted by one of Bill’s patients. The millionaire Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack) has wealth that makes the Harfords look like middle-class pilot fish swimming with sharks. Production designers Les Tomkins and Roy Walker stage the ball shimmering with interior lights for the holidays, a surreal time of year when everything feels heightened. While the couple dances, Alice wonders if they know anyone at the party. Bill confirms they do not. They’re both out of their depth, and Bill will prove to be increasingly so throughout the ensuing 159 minutes.

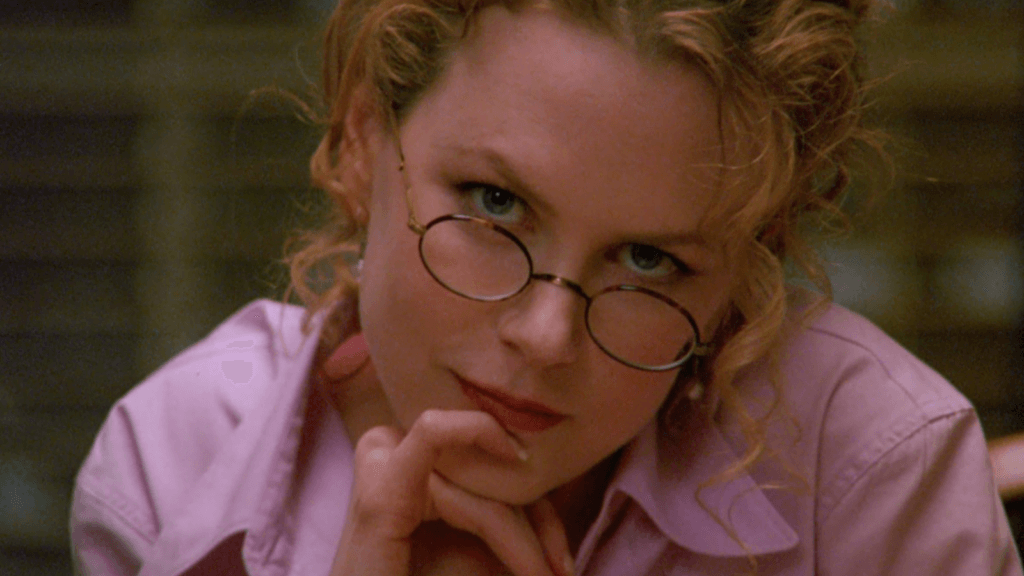

During their dance, Bill notices an old medical school pal, Nick Nightingale (Todd Field), playing piano and leaves Alice to catch up with him. Alice claims she’s going to the restroom but instead heads to the bar, where she meets Sandor Szavost (Sky du Mont), an attractive Hungarian fatcat, who comes on to her during a flirtatious dance. Bill, too, flirts with two models who promise to take him “where the rainbow ends”—a decidedly unattainable place that he never visits, not during that encounter nor any other in the film. Instead, Ziegler needs Dr. Bill upstairs to save an overdosed sex worker (Julienne Davis). After the party, the Harfords return home and channel the evening’s sexual tensions into making love. But the next evening, during another escape from reality, Bill and Alice smoke pot and, clearly influenced, move from verbal foreplay into the film’s most pivotal scene: a dizzying discussion about their flirtations from the night before. All at once, Alice’s tone becomes accusatory—she wants to know why she shouldn’t be jealous of Bill’s flirtation and why Bill isn’t upset about hers. Bill responds that he knows Alice would never be unfaithful because women “just don’t think like that.” Alice reflects, “If you men only knew…” and then proceeds to shut down his claim by recalling, with devastating detail, a memory of a naval officer she once saw and fantasized about during their vacation to Cape Cod.

Before Bill can respond, a call interrupts; he must leave their argument and make a late-night appearance for the family of a deceased patient. Bereaved, Marion (Marie Richardson) welcomes Bill and, having apparently harbored a sexual obsession with him, kisses him and confesses her love mere feet away from the corpse of her deceased father. However comically awkward, the moment confirms Alice’s claim for Bill—women do think like that, a realization that twists the knife of Alice’s confession. When Bill leaves Marion’s apartment, a group of hypermasculine college goons body check him and lash out with homophobic slurs. Afterward, humiliated and emasculated, Bill wanders the city on a series of sexual misadventures. Kubrick’s dark humor emerges in these scenes, as almost everyone Bill encounters—male and female—makes a sexual advance toward him. But, out of his depth, none of his potential trysts work out. Bill, it seems, isn’t even sure how to be unfaithful. A sex worker named Domino (Vinessa Shaw) picks him up, brings him back to her apartment, and asks him what kind of “fun” he wants. Uncertain, he asks, “What would you recommend?” And then his conscience returns when his cell phone buzzes, and it’s Alice on the other end. Instead of following through with Domino, he imagines his wife and the naval officer together—a black-and-white film playing in his mind incessantly. Kubrick refused to allow Cruise on the set when Kidman shot the monochrome sequence and forbade her from telling her husband what was filmed, hoping Cruise’s uncertainty and jealousy might come through in his performance.

During Bill’s late-night walks, the artifice of Eyes Wide Shut becomes increasingly conspicuous. Bill walks down the same city streets, constructed via immaculately detailed but wholly unreal sets in England’s Pinewood Studios, all radiant with deep underlighting from the Christmastime setting and sometimes rear-projected behind Cruise. Re-creating New York, a necessity because Kubrick refused to leave his England home, enhances the dreamlike aura of his mise-en-scène. While filming Full Metal Jacket, a production that led to him recreating a wartorn Vietnam wasteland in England, Kubrick remarked, “Sometimes it is easier to build ‘reality’ than go to it.” He applied that philosophy to Eyes Wide Shut. Based on thousands of photographs, measurements, and actual props from New York, Kurbrick’s production designers and set dressers built four blocks of convincing Greenwich Village locations on the Pinewood backlot. The studio shoot gave Kubrick complete control over the unpredictable lighting conditions, shooting, and design. For Kubrick, the set also supplied him with a memoryscape, drawing on details from his time living in New York City—many of which no longer existed. Kolker and Abrams called the setting “an expatriate’s dream of the New York he once knew.” But the effect, surely intended, imbues the faux nocturnal world Bill explores with the unreal textures of a waking, psychosexual dream shaped by his jealousy.

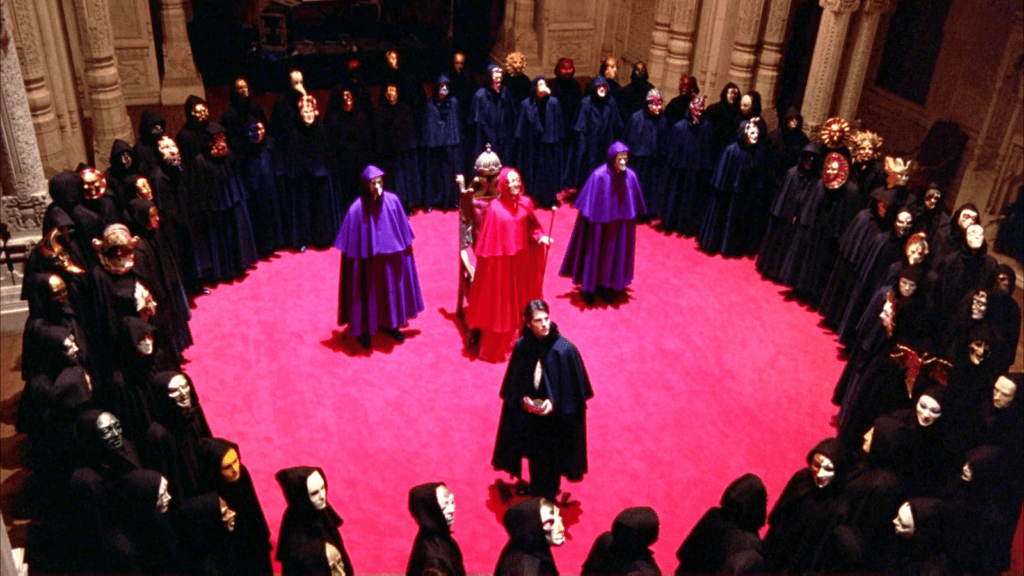

While walking down one of these streets, reeling from his unfulfilled sexual temptations, Bill meets up with his old friend Nightingale after his set at a jazz club. Nightingale confesses that he has another late-night gig— a hush-hush event at an unknown location—where he plays blindfolded. Once, Nightingale laughs, he caught a glimpse of naked women everywhere. Intrigued, Bill insists on crashing the party and pries details from his friend. He sets out to rent the required cloak and mask costume and takes a cab to a Gothic mansion in upstate New York. Bill enters and gives the password Nightingale gave him—“Fidelio,” taken from Beethoven’s opera, meaning “faithful.” Standing on the margins, he bears witness to a ritualized orgy, where figures donning grotesque Venetian masks engage in impersonal sexual acts, the participants oddly pantomiming kisses and oral sex through their masks, even at the height of their undulations. One of the naked, masked women, who somehow recognizes Bill behind his disguise, warns him to leave. But Bill does not heed the warning and, soon identified as an interloper, he is captured by the ominous cloaked men behind this proceeding, exposed, and nearly punished. At the last moment, he is “redeemed” by the self-sacrificing woman concerned for his safety. Released and told never to inquire about the evening again, Bill returns home, feeling lucky to be alive.

Despite the presence of sexuality throughout the film, Eyes Wide Shut rarely attempts to be sexy. Instead, the film links Bill’s attempts at illicit sexuality with death: When Bill later returns to Domino’s apartment only to find her roommate, Sally (Fay Masterson), he learns that Domino has just discovered she’s HIV positive—tragic for her; a close call for Bill. When Bill returns his costume to Mr. Milich (Rade Šerbedžija), he finds the renter’s daughter (Leelee Sobieski) has become an exploited victim of her father, who attempts to sell her willing services to Bill. The orgy scene carries a stigma of nightmarish dread followed by a menacing threat. Regardless of the relative omnipresence of nudity and sex in the film, these moments are more about linking unfaithful sexuality with death and apprehension than arousal. Moreover, the film’s sexual scenes away from Alice are not meant to be erotic or real but rather distanced and ethereal, their intimacy and eroticism removed by their participants’ lack of real human connectivity. Cruise’s one brief onscreen sexual encounter with Kidman feels all the more realistic and meaningful by comparison.

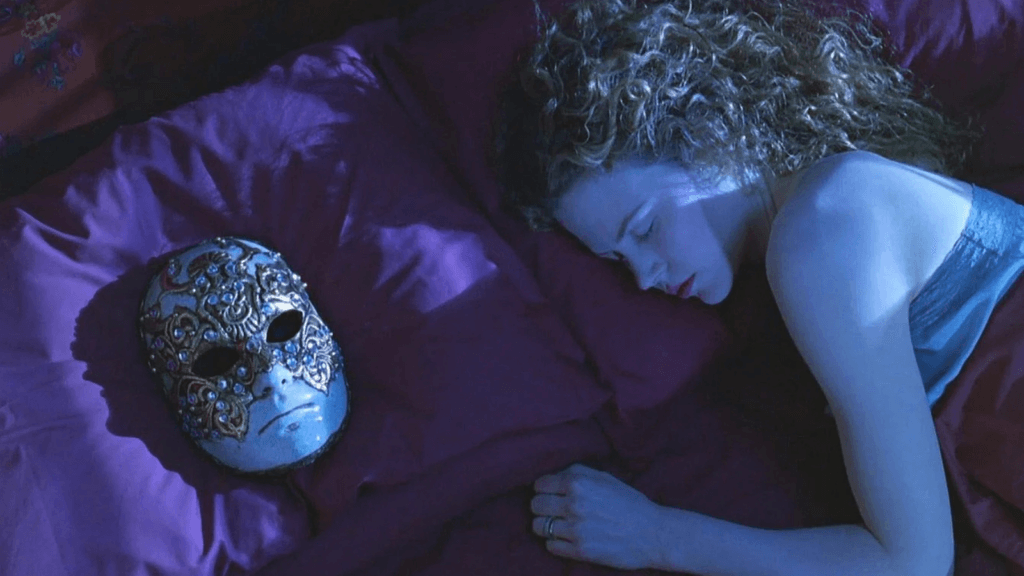

When Bill returns to the sanctuary of their marital bed, Alice appears to be having a laughing nightmare. He asks her to tell him about the dream. She weeps as she confesses to a devastating, post-apocalyptic, orgiastic encounter that begins with the dreaded naval officer and escalates into countless men. At the sight of her husband’s presence in the dream, she laughs mockingly. Alice weeps at the cruelty of her unconscious thoughts, and Bill’s wounded ego isn’t helped. The next morning, Bill attempts to follow up with Nightingale but discovers, thanks to a flirtatious hotel clerk (Alan Cumming), that Nightingale was taken away by men early in the morning. Bill returns to the scene of the orgy and stands outside the estate’s front gate, where he’s issued a written warning to stop his inquiries—a moment given a chilling undercurrent from the film’s maddening, repetitive piano score by Jocelyn Pook. Bill soon learns of a reported beauty queen who overdosed and, in the morgue, sees that she was the same woman who saved him at the orgy and whose overdose he treated at Ziegler’s party. As his imagination runs wild, he notices a mysterious man following him.

Most commonly associated with confident, heroic, save-the-day roles, Cruise plays the weakest and most emotionally vulnerable character of his career in Eyes Wide Shut. Kubrick presents him as an outsider, unable to penetrate the sexual world of the elite class. Despite being a well-paid doctor, he does not know anyone at Ziegler’s party, nor does he qualify for an invite to the orgy. When Bill arrives in a cab at the orgy instead of a limo, he’s instantly outed as someone who doesn’t belong. And so, feeling thoroughly inadequate both sexually and as a member of New York’s high-end social circle, Bill clings to the little authority he has: his medical license and his money. While he attempts to learn about the orgy and what happened to Nightingale, he comically flashes his doctor’s license like a detective’s badge to several thoroughly unimpressed New Yorkers: the costume shop owner, Domino’s roommate, a server in a diner, and the hotel clerk. If that doesn’t work, he dishes out cash to buy their favor, treating everyone as though they have a price. One can guess he imagines himself as an Important Man, yet Alice’s confession and his ejection from the orgy have bruised his ego. In an amusingly cruel streak, Kubrick casts Cruise against type. On the surface, he has all the hallmarks of a successful, good-looking family man. Yet, even as he tries to restore his ego through a meaningless sexual encounter, whether by circumstance or fear, he cannot manage to go through with it, nor can he earn anyone’s respect with his doctor’s badge or wallet full of cash.

Later, Ziegler requests to see Bill at his obscenely lavish home. Bill’s host awkwardly offers a drink and a game of billiards before revealing he, too, was at the orgy. Ziegler attempts to convince Bill that the night’s theatrics were just that: a show designed to frighten him. He assures Bill that the sex worker’s death was an accidental overdose and that Nightingale is on a plane to his Seattle home. He encourages Bill to leave it alone, explaining that he’s meddling with the lives of influential people. “If I told you some of their names […] I don’t think you’d sleep so well,” he says. Once again, Bill returns home, shaken but also relieved, only to see that Alice has found his missing Venetian mask from the orgy and placed it on his pillow. With this, Bill weeps in a scene mirroring Alice’s earlier dream confession and says he’ll tell her everything. After talking it through, and after Bill apologizes, they come to an understanding: both may have fantasies, but some dreams can be just as dangerous as reality. Hopefully, they can know the difference in the future. And as for their shared cravings for emotionally detached sexuality, Alice offers her four-letter-word solution to reinvigorate their marriage: “Fuck.”

Eyes Wide Shut recognizes the reality of desires and fantasies, conscious and unconscious, while encouraging an open dialogue about them. Themes of masks that conceal true identities, eyes (open and shut), and states of consciousness and dreaming have a symbolic place within the film. Perhaps Kubrick, long happily married to his wife Christiane, sought to complete a sort of testimony to how a strong enough bond can accept the need for detached fantasy but also acknowledge and work through how “No dream is just a dream” within their marriage. Certainly, the coda of the film engrains the filmmaker’s intentions. These intentions may have influenced Kubrick’s choice to cast a real-life couple in the film, and his choice couldn’t have been more correct. Wearing down their superstar gloss with his repeated takes, Kubrick draws profound performances out of his stars, particularly Kidman and her staggering delivery of several long, upsetting monologues in Kubrick’s extended shots. With the pairing of these stars, there’s an undeniable onscreen-offscreen intrigue for the viewer, as we suspect, in some way, the filming has penetrated their married lives to give us some voyeuristic insight (even more so now, after their divorce). Kidman’s peak moment comes the night after Bill’s confession, where she’s shown smoking, her makeup gone, and her eyes bloodshot from crying all night. An unprecedented transformation has taken place: Kidman appears not like a movie star, nor even like her Central Park West elite character, but like a human being stripped of all her veneers to reveal the bare, crushed humanity underneath.

Warner Bros. marketed the film mainly as a showcase for Cruise and Kidman. Despite rumors to the contrary, these actors gave everything to their director, and their uncanny performances, unique within their respective careers, attest to this. They sacrificed much over two years for what ultimately became an art film, something with which neither performer was familiar. Of course, defining (or not) Schnitzler’s story and Kubrick’s film through advertisements was another matter altogether. The studio’s promotional team loaded the movie trailer with all the signs of an “erotic thriller,” dwelling on dramatic images without dialogue, confident that the “Cruise Kidman Kubrick” names on the screen would be enough to sell the picture. Never mind if it led to audiences having misaligned expectations. To be sure, although it’s intended for mature adults, Eyes Wide Shut does not belong in the thriller genre. With a thriller, Bill’s would-be sexual adventures might amount to something beyond his jealous point of view; the thriller elements would instead be vindicated when Bill uncovers that the orgy was just as dangerous as he suspected, a revelation he never makes. If he uncovers a secret society of rich orgy-goers who rough up a piano player who can’t keep a secret and let a drug-addicted prostitute die, he also falls victim to their ruse. The advertising also ignores the dark humor found in the nightmarish surreality of Bill’s misadventures. But then, the unique tone of Kubrick’s film is difficult to pin down in its entirety, much less so in promotional material.

When Eyes Wide Shut opened in July of 1999, many critics and viewers were baffled or altogether shocked by its displays of sexuality and confronting ruminations on infidelity. Critics wrote positive to lukewarm reviews, but few declared it a landmark. Many cited their aversion to Warner Bros.’s release of an R-rated version into theaters that digitally blocked sexually graphic material cited as problematic by the MPAA—an artistic violation of Kubrick’s final film. Rather than accept box-office death with an NC-17 rating, the studio made the controversial decision for these digital alterations (an alternative considered by Kubrick to earn his contractually obligated R-rating) that placed digital figures in front of sex acts during the film’s orgy sequence. The studio later acknowledged their error and released Kubrick’s uncut version on various home video formats. As always, there were a number of complete dissenters, including Andrew Sarris’ assessment for the New York Observer, which described the film as “control-freak unreality.” Entertainment Weekly’s review thought the film’s revelations were unaffecting. Other critics complained about Kubrick’s intentionally slow pace or deliberately unnatural dialogue delivery by his actors, citing the director’s long-standing detached quality as an encumbrance to enjoying the picture.

Such responses failed to recognize the potential that little of Eyes Wide Shut takes place in what one could call “reality.” Few critics at the time considered this possibility. Kubrick and Frederic Raphael’s screenplay never intended realism, only to closely follow Schnitzler’s “dream novel” and show a world informed by Bill’s jealousy. As a result, Eyes Wide Shut cannot be pigeonholed into a single genre or sole interpretation, just like Kubrick’s pictures from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) to Barry Lyndon (1975) to The Shining (1980). Viewers must dissect, interpret, and consider minor behavioral quirks and visual touches, questioning seemingly self-contained scenes and encounters against the larger whole—just as a psychoanalyst would interpret a dream. Kubrick’s faith in his audience’s willingness to investigate themselves for meaning in film is also his most significant characteristic as an artist. He refuses to give answers, inviting viewer participation that often leads to rampant theories and speculation, ensuring his films’ longevity. In Eyes Wide Shut, the viewer must discover where the characters cross the line between dream and reality. That journey of breaking through can be confronting, repulsive, shocking, hilarious, unsettling, and emotionally eviscerating, but never short of engaging. With his posthumous release, accusations of Kubrick’s emotional coldness as a filmmaker have never had a more potent counterargument.

Given the timing of Kubrick’s death and the film’s release a few months later, Eyes Wide Shut would undergo another kind of scrutiny. Kubrick was famous for tinkering with his films immediately after their release and making edits based on initial audience reactions. Some have speculated whether the version released in July of 1999 was what Kubrick would have wanted. Before his death, Kubrick had screened the film for its superstar leads, along with several executives from Warner Bros.—the studio that had honored a long-held deal for the director to work in England, far away from Hollywood, in an unprecedented arrangement that allowed him to have final cut on whatever project he desired. Those in attendance attest to Kubrick’s satisfaction with the film. Kubrick told Jan Harlan, the production’s executive producer and his brother-in-law, that he felt it was his best film to date. Even so, Kubrick’s fervent followers have questioned whether the director would have changed anything about Eyes Wide Shut. Was the movie unfinished, or did Kubrick have more tinkering to do? What would Kubrick have changed? Does it matter? Such theorizing may be indicative of the Kubrick viewer, accustomed to conspiracy theories and mining his work for hidden meaning. But the speculation achieves little beyond indulging the imagination of enthusiasts, some of whom have taken it upon themselves to create fan edits or discredit the film as it exists.

Whether deemed his final masterpiece, a late-career misfire, or an incomplete film, Eyes Wide Shut is perhaps Stanley Kubrick’s most divisive film. Whereas many of the director’s masterpieces have been canonized in their respective genres—comedy (Dr. Strangelove, 1964), science fiction (2001: A Space Odyssey), war (Full Metal Jacket), horror (The Shining), historical epic (Spartacus)—his final film continues to defy classification and resist the almost universal acclaim given to his other output. Its formal daring, confronting themes, and challenging presentation remain more interpretive and inaccessible than any other film to his name. Given that it preoccupied Kubrick for much of his life and, as argued by many scholars and commentators, supplies a summa to his career-long preoccupations, the film continues to be examined and debated for its portrait of a masculine crisis in the face of female desire, surreal cinemascape, and unconventional filmmaking. Many Kubrick films invite interpretation, particularly those in the second half of his career. But the dreamlike nature of Eyes Wide Shut only amplifies that quality, leaving a rich wellspring that, like Kubrick’s best films, offers a bottomless resource to explore.

Bibliography:

Chion, Michel. Kubrick’s Cinema Odyssey. British Film Institute, 2001.

Karger, Dave. “Closing their ‘Eyes Wide Shut.’” Entertainment Weekly. 17 October 1997. https://ew.com/article/1997/10/17/closing-their-eyes-wide-shut/. Accessed 14 December 2024.

Kolker, Robert P., and Nathan Abrams. Eyes Wide Shut: Stanley Kubrick and the Making of this Final Film. Oxford University Press, 2019.

—. Kubrick: An Odyssey. Pegasus Books, 2024.

Ljujic, Tatjana, et al. (editors). Stanley Kubrick: New Perspectives. Black Dog Press, 2015.

LoBrutto, Vincent. Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. D.I. Fine Books, 1997.

Nelson, Thomas Allen. Kubrick, Inside a Film Artist’s Maze. New and expanded ed. Indiana University Press, 2000.

Sperb, Jason. The Kubrick Facade: Faces and Voices in the Films of Stanley Kubrick. Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Philips, Gene D., editor. Stanley Kubrick: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Walker, Alexander, et al. Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis. Rev. and expanded. Norton, 1999.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review