The Definitives

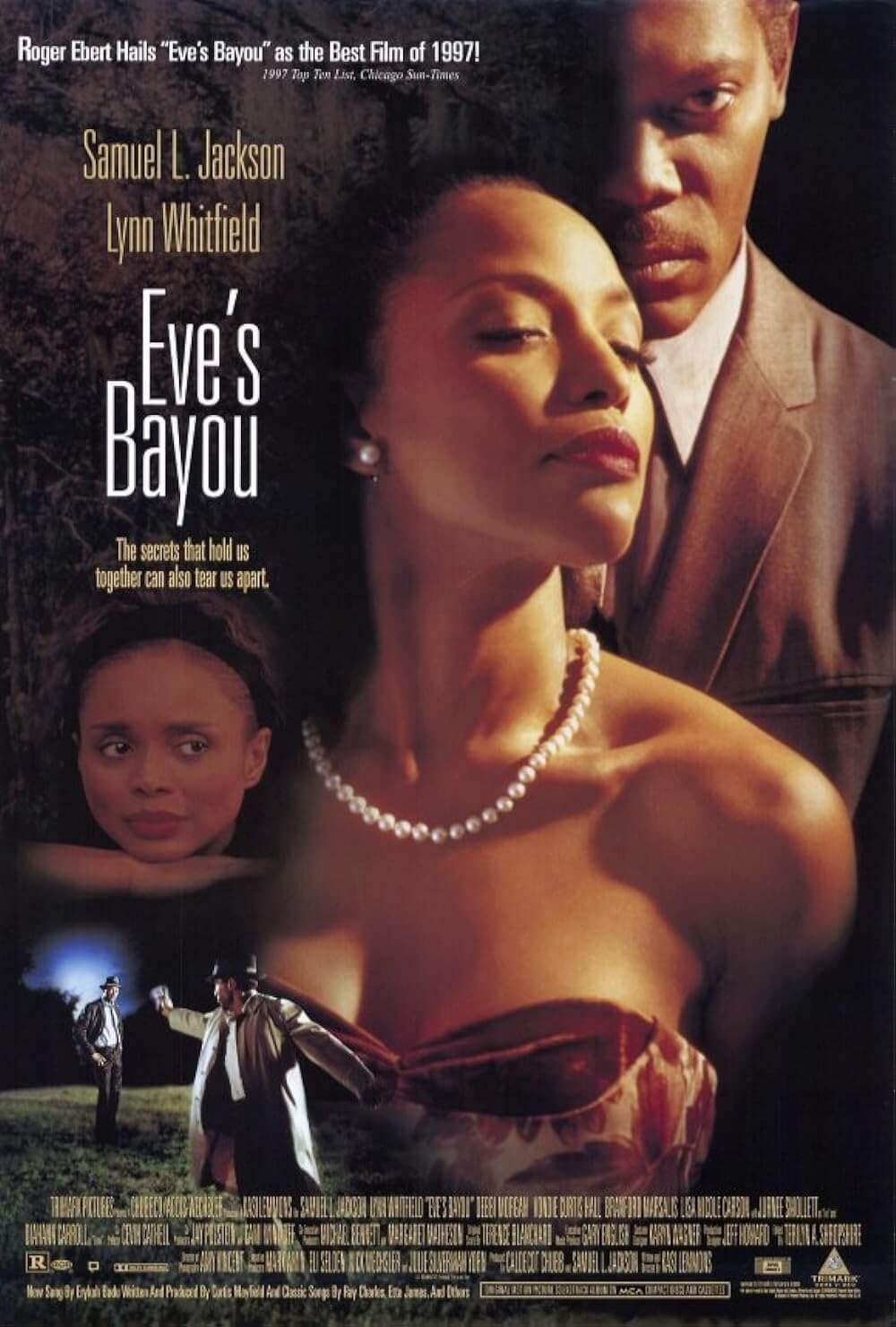

Eve’s Bayou (1997)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Eve’s Bayou opens with a line as haunting as they come: “Memory is the selection of images, some elusive, others printed indelibly on the brain.” This is the voice of Eve Batiste, who continues, “The summer I killed my father, I was ten years old.” With this layered introduction and hints of patricide and ambiguity, the mysterious film, written and directed by Kasi Lemmons, immerses us in a past filtered through the recollections of its protagonist—the child of an affluent, bourgeoisie family in a predominantly Black, non-urban community. Showcasing an aspect of the Black experience rarely depicted in the 1990s, or beyond for that matter, Eve’s introductory lines establish a coming-of-age tale about a child discovering the tangled social realities of those around her. The story seems to pour out from Eve’s mind with the first images, which show two figures engaged in sexual activity, albeit through high-contrast monochrome visuals—as though envisioned in a dream or premonition and reflected on a human eye. Leaving questions about this potentially unreliable narrator and the events that led to her father’s death, the film is part murder mystery, part bildungsroman, and part investigation of life’s many equivocations, all steeped in a Southern Gothic atmosphere, supernatural mysticism, family curses, and the scars of American slavery. A moving and personal work, Eve’s Bayou inhabits the boundaries between dreams and reality, childhood and adulthood, perception and imagination, like an indistinct memory from which the fog always seems to be lifting yet never does.

Set in the early 1960s, the story follows the Batistes, a well-to-do Black Creole family from Louisiana. The subject matter proved unique for any filmmaker in 1997, much more so for Black filmmakers. To be sure, Lemmons deepens the usual forms of racial representation in the 1990s, giving audiences not an alternative to the urban settings or gang culture that dominated Black cinema in the decade, but another layer to the Black experience then embraced by mainstream Hollywood. In that sense, the film was far ahead of its time and belongs on a shortlist of films, including Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) and Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996), which expose another dimension beyond the male-centric voice of Black filmmakers from the 1990s. Most exceptionally, Eve’s Bayou avoids falling into stereotypes of racial representation, while also resisting simplistic narrative or emotional beats. The film is a soulful, personal, and even supernatural drama with many ties throughout cinema and literature. The closest comparison might be Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (1982), a ghostly tale of youth and its perspective on the complicated lives of adults. But it also contains the spirituality and magical realism of Toni Morrison’s writing, specifically her 1987 novel Beloved, offering equal emotional depth and intellectual weight.

The opening voiceover spoken by Eve Batiste explains her family’s complicated history of African slavery, witchcraft, and land ownership in the town of Eve’s Bayou. The Batistes descend from a woman named Eve, who saved her one-time enslaver, General Jean-Paul Batiste, using voodoo medicine. As a reward, she was given her freedom and the title’s land by Batiste. She then fathered his 16 children “out of gratitude,” Eve claims. This rich and storied past, afflicted with a hint of magic and sexual taboos of the period, reverberates in the story, following the Batistes throughout history in the narrative’s present. The family remains affected by sexual transgressions and supernatural premonitions of various kinds, while its members experience violations of trust that raise questions about the bonds between them. As the story unfolds, their experiences have a complexity that resists an essentialist or morally clear explanation, not unlike their complicated family lineage. Even the events in the narrative remain unclear, shaped by children’s perspectives. But the images of Eve’s memories are both ephemeral and stark. “Each image is like a thread,” her voiceover explains in the final shot. “Each thread woven together to make a tapestry of intricate texture. And the tapestry tells a story. And the story is our past.”

The opening voiceover spoken by Eve Batiste explains her family’s complicated history of African slavery, witchcraft, and land ownership in the town of Eve’s Bayou. The Batistes descend from a woman named Eve, who saved her one-time enslaver, General Jean-Paul Batiste, using voodoo medicine. As a reward, she was given her freedom and the title’s land by Batiste. She then fathered his 16 children “out of gratitude,” Eve claims. This rich and storied past, afflicted with a hint of magic and sexual taboos of the period, reverberates in the story, following the Batistes throughout history in the narrative’s present. The family remains affected by sexual transgressions and supernatural premonitions of various kinds, while its members experience violations of trust that raise questions about the bonds between them. As the story unfolds, their experiences have a complexity that resists an essentialist or morally clear explanation, not unlike their complicated family lineage. Even the events in the narrative remain unclear, shaped by children’s perspectives. But the images of Eve’s memories are both ephemeral and stark. “Each image is like a thread,” her voiceover explains in the final shot. “Each thread woven together to make a tapestry of intricate texture. And the tapestry tells a story. And the story is our past.”

Eve’s Bayou contains a mood that follows the traditions of Southern Gothic motifs. Lemmons has acknowledged that she drew from Southern Gothic literature, including the works of Toni Morrison and Tennesee Williams, though Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner seem to have unconsciously influenced the writer-director as well. Lemmons confronts uncertainties about memory, history, and the world with her characters. Her film takes place in a setting of old houses that have lasted generations in a neighborhood teeming with mysteries and secrets—an America far removed from false idylls and self-mythologizing, which the Southern Gothic regularly questions. Rather, there’s a conflicting history of trauma and agency where the film’s Black community makes its home, where the thriving Batiste family will be marked by melancholy, crimes of passion, and the ghosts of those who have passed. Situated amid ancient swamps filled with bald cypress trees and Spanish moss, the Louisiana locations are stunning. But their beauty is complicated by the social and historical realities associated with them. Following the Southern Gothic’s aesthetic agenda, Lemmons writes characters who are or will be damaged; they might even be delusional or influenced by supernatural forces. Whatever the cause, they are dualistic, reflecting the history of slavery and romance that makes up the Louisiana town while also deviating from clear moralistic boundaries and lessons.

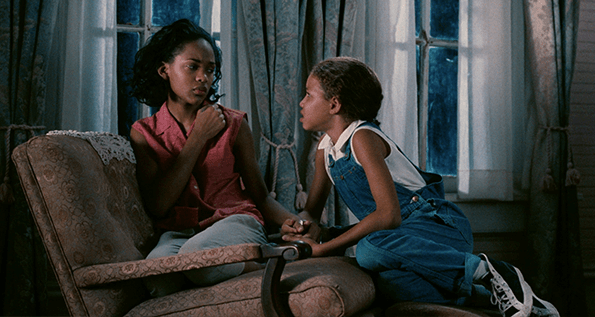

Lemmons centers her film on the Batiste family, headed by the philandering Dr. Louis Batiste (Samuel L. Jackson), a small-town doctor well aware of his prominent position in the community, especially his popularity among women. He is married to Roz (Lynn Whitfield), an elegant and sophisticated woman. They have three children: the fourteen-year-old Cisely (Meagan Good), who worships her father; the ten-year-old Eve (Jurnee Smollett), a rambunctious tomboy; and the nine-year-old Poe (Jake Smollet), who seems to be in his own preadolescent world and oblivious to the shifting dynamics between his parents and older sisters. The story is told from the perspective of Eve, whose Grand Mere (Ethel Ayler) always seems to be working in the kitchen, while her cursed Aunt Mozelle (Debbi Morgan) has lost three husbands to violent deaths. Eve’s father remarks that his sister Mozelle is “not unfamiliar with the inside of a mental hospital.” He looks down on his sister for her “counseling”—psychic readings, a spiritual alternative to his conventional medicine, manifested in a genuine sixth sense that allows her to locate those who have gone missing and to see the dead. Eve might have the same gift, spied in her psychic dreams of frightening black-and-white images. Still, such things, including Louis’ evident sexual indiscretions, remain hidden beneath the family’s outward appearance of respectability.

However, Eve begins to question the carefully constructed family veneer after the events of a community party at the Batiste home—an extended opening sequence introduces the characters as adults dance and flirt, while the children clamor among them, and everyone gets a little drunk. Resentful that her father dances with Cisely and not her, Eve steps away from the commotion to the carriage house, where she falls asleep, only to be awakened sometime later by the sounds of her father engaged with another woman, Matty Mereaux (Lisa Nicole Carson). Shocked, she interrupts them, prompting her father to unconvincingly downplay what happened. Later, Eve tells Cisely what she saw, but entrenched in father worship, Cisely refuses to believe it. Cisely presents an alternate, innocent series of events, visualized in a mirror, demonstrating how far the character will go to alter her memories to make them easier to process. Even so, Eve’s suspicions about her father continue, especially when she accompanies him on house calls. He sends her outside while he stays behind to treat a woman in bed who asks, “Can you give me something for the pain?” with a loaded glance. “To a certain type of woman, I am a hero,” he explains later. “I need to be a hero.” These tensions between sisters, between parent and child, and between husband and wife amplify over the course of the story. The crucial moment comes when Cisely confesses to Eve about something that happened between her and their father one night, and Eve decides to act.

However, Eve begins to question the carefully constructed family veneer after the events of a community party at the Batiste home—an extended opening sequence introduces the characters as adults dance and flirt, while the children clamor among them, and everyone gets a little drunk. Resentful that her father dances with Cisely and not her, Eve steps away from the commotion to the carriage house, where she falls asleep, only to be awakened sometime later by the sounds of her father engaged with another woman, Matty Mereaux (Lisa Nicole Carson). Shocked, she interrupts them, prompting her father to unconvincingly downplay what happened. Later, Eve tells Cisely what she saw, but entrenched in father worship, Cisely refuses to believe it. Cisely presents an alternate, innocent series of events, visualized in a mirror, demonstrating how far the character will go to alter her memories to make them easier to process. Even so, Eve’s suspicions about her father continue, especially when she accompanies him on house calls. He sends her outside while he stays behind to treat a woman in bed who asks, “Can you give me something for the pain?” with a loaded glance. “To a certain type of woman, I am a hero,” he explains later. “I need to be a hero.” These tensions between sisters, between parent and child, and between husband and wife amplify over the course of the story. The crucial moment comes when Cisely confesses to Eve about something that happened between her and their father one night, and Eve decides to act.

Besides Lemmons’ use of the literary flourishes of Southern Gothic expressionism, she also accesses personal memories from her childhood experiences. Many of Eve’s experiences in the film derive from Lemmons’ recollections and creative work. For instance, as a child repeatedly stricken with pneumonia, the director often suffered hallucinations, which she later translated into Eve’s nightmarish premonitions. Lemmons also wrote short stories about a fortune teller; her Great Uncle Tony, who had cerebral palsy and whose family looked after him; and the fictional town of Eve’s Bayou—memories and ideas that had been with her for many years, which she then incorporated into her film. Although Lemmons did not grow up in the South, she told interviewer Ann Brown that her parents originated from Georgia and Louisiana, and they told her stories about their lives there. When thinking about those stories and her writing, Lemmons resolved to write a screenplay about a predominantly Black community like her hometown, having never seen a film like that before. Scholar Tarshia L. Stanley argues, “Eve’s Bayou is the filmmaker’s attempt to go home, to understand this strange, rich, historical place from which her familial roots spring.”

Eve’s Bayou marked Lemmons’ directorial debut. Before developing her first screenplay, she was best known for her acting in supporting roles next to Jodi Foster in The Silence of the Lambs (1992), Jean-Claude Van Damme in Hard Target (1993), and Virginia Madsen in Candyman (1995). Frustrated with playing the Black friend, she was encouraged by her husband, Vondie Curtis-Hall (who plays the mysterious Julian Grayraven in the film), to explore her fiction and show her stories to others. This led to her writing Eve’s Bayou and making a proof-of-concept short film called Dr. Hugo, in which Curtis-Hall plays a version of Dr. Batiste. Dr. Hugo establishes several themes from her feature film, including her interest in a child’s skewed observations of the adult world. The short film reached Samuel L. Jackson, who agreed to star in Eve’s Bayou and co-produce. The project was uncommon at the time since most African American filmmakers consisted of men, except for names like Dash and Dunye. The notion of a Black woman director was fairly uncommon, and almost none had created box-office performers. Still, Lemmons’ project was greenlit and completed on a budget of $4 million. The film would go on to earn $14 million, leading to Lemmons’ successful career behind the camera, including films such as The Caveman’s Valentine (2001), Talk to Me (2007), Black Nativity (2010), Harriet (2019), and Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance with Somebody (2022).

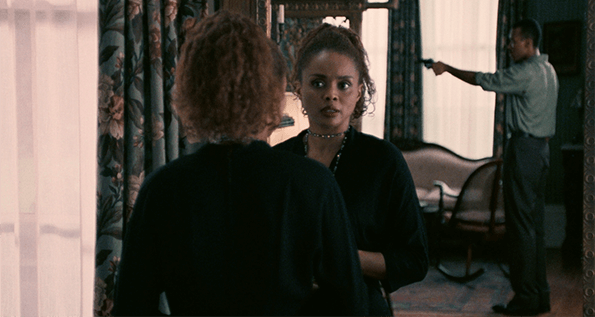

Though her later output would become more conventional and straightforward, Lemmons’ work on Eve’s Bayou adopts novelistic, unresolved questions and narrative ambiguities. Consider the thick scar tissue on the Batiste family, from the origins of their name to the more recent history involving Mozelle. Morgan gives a sorrowful performance as Eve’s doomed aunt who can accurately see the futures of others, except those of the men she loves. In one scene, Mozelle brushes Eve’s hair in front of a large mirror and recounts the fate of her first husband, Maynard, and his confrontation with her lover, Hosea, which ended in Maynard’s death. Trimark Pictures, who was producing the film, asked Lemmons to remove the scene, given that it consisted of several minutes of backstory that would seem to stall the narrative’s forward momentum. But she resolved to stage the scene in dramatic visual terms, rendering it as more than mere backstory but also a key thematic sequence. As Mozelle remembers, her words conjure images reflected in the mirror—perhaps a projection from Mozelle’s mind, perhaps the imprint of spirits only visible to Mozelle and Eve, who share a supernatural gift. Both watch as Mozelle approaches the mirror, her story playing out before them, as though she were reliving the scene reflected by her memories. “In this exchange,” writes Stanley, Eve “learns the power of the conjure woman to reshape interpretation, reinvigorate memory, and rewrite history.” The scene feeds into a central motif in Eve’s Bayou concerning the pliability of memories and re-experiencing them. The mirror becomes the device by which Mozelle and Eve can recollect events reflected in their mind’s eye.

Though her later output would become more conventional and straightforward, Lemmons’ work on Eve’s Bayou adopts novelistic, unresolved questions and narrative ambiguities. Consider the thick scar tissue on the Batiste family, from the origins of their name to the more recent history involving Mozelle. Morgan gives a sorrowful performance as Eve’s doomed aunt who can accurately see the futures of others, except those of the men she loves. In one scene, Mozelle brushes Eve’s hair in front of a large mirror and recounts the fate of her first husband, Maynard, and his confrontation with her lover, Hosea, which ended in Maynard’s death. Trimark Pictures, who was producing the film, asked Lemmons to remove the scene, given that it consisted of several minutes of backstory that would seem to stall the narrative’s forward momentum. But she resolved to stage the scene in dramatic visual terms, rendering it as more than mere backstory but also a key thematic sequence. As Mozelle remembers, her words conjure images reflected in the mirror—perhaps a projection from Mozelle’s mind, perhaps the imprint of spirits only visible to Mozelle and Eve, who share a supernatural gift. Both watch as Mozelle approaches the mirror, her story playing out before them, as though she were reliving the scene reflected by her memories. “In this exchange,” writes Stanley, Eve “learns the power of the conjure woman to reshape interpretation, reinvigorate memory, and rewrite history.” The scene feeds into a central motif in Eve’s Bayou concerning the pliability of memories and re-experiencing them. The mirror becomes the device by which Mozelle and Eve can recollect events reflected in their mind’s eye.

Mozelle remains a key character in Eve’s Bayou because she represents what Eve may become. Although Eve’s gifts have not fully developed, they materialize in rudimentary dreams, such as Eve’s nightmare after the opening party scene. In a montage of seemingly unrelated yet highly symbolic imagery, Eve dreams of her father’s infidelities and the death of Mozelle’s third husband in a car accident—unclear images in black-and-white, accented by the appearance of a spider, which recurs in the film. The spider imagery may continue the metaphor of a tapestry that weaves together the past, albeit by spinning a web. It may also suggest the fate that awaits both Mozelle and Eve, who struggle to understand the world, even with their extra-sensory abilities. Mozelle feels cursed by her fate, afraid that she may end up like a local witch doctor, Elzora (Diahann Caroll), who lives on the outskirts of town and maintains a fortune teller’s tent at the marketplace. Until she falls in love with one of her clients, Julian Grayraven, whose wife has left him, she sees the world as a painful place. Mozelle questions whether “it will all come clear” when people die. “And then we’ll say, ‘So that was the damn point.’ And sometimes, I think there’s no point at all, and maybe that’s the point. All I know is most people’s lives are a great disappointment to them, and no one leaves this earth without feeling terrible pain.”

In moments such as this, Lemmons’ screenplay captures the raw, poetic language of the Southern Gothic, where romanticism combines with occasionally torrid and transgressive subject matter. The narrative turns when Cisely recounts a traumatizing experience to Eve. Late one night, after her parents finish arguing, Dr. Batiste’s eldest daughter finds him resting in a chair in Uncle Tommy’s room, and she attempts to comfort him. By this time in the film, Lemmons has established Cisely’s fixation on her father, her resentment of her mother, and her sense of entitlement as her father’s favorite. In Cisely’s account, she kisses her father, platonically at first, then romantically. The kiss becomes forced on his part, and when she pulls away, he slaps her. When Cisely tells Eve what happened, a thread is pulled, and the family begins to unravel. Determined to defend her sister (“I’ll kill him for hurting you,” she declares), Eve resolves to visit Elzora when she suspects the worst of her father. She acquires his hair for a voodoo ritual that she hopes will kill him. When that fails in a twisted manipulation by Elzora involving a wax coffin, Eve sets into motion a series of events that prompt the suspicions of Matty Mereaux’s cuckolded husband Lenny (Roger Guenveur Smith), leading him to seek revenge. When Lenny approaches the local bar to confront and ultimately kill Dr. Batiste, he walks along the train tracks—a shadowy figure, with long, flailing spider webs illuminated in the moonlight, suggesting that Eve’s plan has become untethered. To be sure, the reality of her father’s death, which she witnesses, proves too much for Eve to bear.

In the final scenes, Eve looks through her father’s belongings and finds a letter he wrote, explaining his version of what happened that night with Cisely. Eve accepts his version, knowing first-hand of Cisely’s ability to alter her perceptions to align with her needs, evidenced by Cisely visualizing for Eve what happened between their father and Mrs. Mereaux in the carriage house. Confronting her sister, Eve presents her hands to Cisely as Mozelle does with her customers. But the truth remains suspect, clouded by perceptive bias. Lemmons’ screenplay offers two explanations, those presented by Cisely and her father’s letter, and both prove confronting and emotionally devastating in their own ways. In either case, the tragic conclusion leaves scars on the family legacy and Eve’s memories. The only third-party view of what happened resides with Uncle Tommy, the mute witness in the room, who reacts harshly to the incestuous kiss and knocks over a crystal decanter. But Uncle Tommy—a character who has the answers to the film’s questions but tragically cannot communicate them—would be excised from the theatrical version. After running test screenings, the distributors at Trimark Pictures insisted that Lemmons remove the scenes with Uncle Tommy, suggesting both his disability and the added frustration of undisclosed answers might frustrate audiences. As a result, Lemmons cut several minutes from the picture to remove Uncle Tommy, which she later restored in the 115-minute Director’s Cut version.

In the final scenes, Eve looks through her father’s belongings and finds a letter he wrote, explaining his version of what happened that night with Cisely. Eve accepts his version, knowing first-hand of Cisely’s ability to alter her perceptions to align with her needs, evidenced by Cisely visualizing for Eve what happened between their father and Mrs. Mereaux in the carriage house. Confronting her sister, Eve presents her hands to Cisely as Mozelle does with her customers. But the truth remains suspect, clouded by perceptive bias. Lemmons’ screenplay offers two explanations, those presented by Cisely and her father’s letter, and both prove confronting and emotionally devastating in their own ways. In either case, the tragic conclusion leaves scars on the family legacy and Eve’s memories. The only third-party view of what happened resides with Uncle Tommy, the mute witness in the room, who reacts harshly to the incestuous kiss and knocks over a crystal decanter. But Uncle Tommy—a character who has the answers to the film’s questions but tragically cannot communicate them—would be excised from the theatrical version. After running test screenings, the distributors at Trimark Pictures insisted that Lemmons remove the scenes with Uncle Tommy, suggesting both his disability and the added frustration of undisclosed answers might frustrate audiences. As a result, Lemmons cut several minutes from the picture to remove Uncle Tommy, which she later restored in the 115-minute Director’s Cut version.

As questions linger and the story’s spiritual and more grounded elements swirl about, the narrative is catapulted forward by Smollet’s performance as Eve. What an uncommonly terrific child performance she gives. It never feels like Smollet is reading lines or play-acting for the camera, as it often does with young performers. Rather, she offers a natural character whose energy and charm make every emotion—whether it’s the simple infighting with her sister, the practicing of voodoo on a sock monkey, or the sense of betrayal she feels toward her father—seem genuine. Meagan Good is also exceptional, navigating among Cisely’s states of jealousy, defiance, and anger with all the self-absorption of a confused teenager. But then, Eve’s Bayou is a film brimming with superb performances. Even Jackson manages to evoke sympathy as a flawed and selfish man; he carefully avoids turning his character into an outright predator, even though Louis’ final letter of explanation to his family brings about knotty feelings of fatherly devotion and betrayal. Lemmons’ script allows her characters to exist between polarized moral extremes, where their actions remain uncertain and conjure a rush of emotion, and it proves to be meaty material for her actors.

Lemmons demonstrates an incredible control of her craft, amounting to one of the most impressive directorial debuts in film history. Of course, she knew to develop strong collaborations behind the camera. Among them, her composer and cinematographer elevate Eve’s Bayou. The film marked the first of four collaborations between Lemmons and composer Terrance Blanchard as of this writing. Although less expressive and jazzy than his many scores for Spike Lee, Blanchard’s music haunts the picture, sometimes adding the pluck of Eve’s perspective, sometimes echoing the many cultural influences sewn into this community. Blanchard’s enigmatic notes dance around the film’s complex characters and the Southern Gothic atmosphere, with its touches of the ambiguous and supernatural. Elsewhere, Eve’s Bayou’s textured images of a vivid and detailed community on location in Louisiana—a place with a history, not a movie set constructed of quickly assembled façades—were beautifully captured by cinematographer Amy Vincent. Lemmons and Vincent worked from a fully storyboarded visual template, but the images inhabit the gorgeous, textured soup of earthy colors found in Rembrandt’s paintings. The film’s images are juxtaposed by the high-contrast black-and-white photography used to create visions—Mozelle’s appear clear and potent, and Eve’s visions look more fractured and unpolished. Lemmons and Vincent’s visual work on the film is both multifaceted and stunning.

One of the most successful independent films released in 1997, Eve’s Bayou earned the attention of audiences drawn to Black stories and the popularity of Samuel L. Jackson. The film was also a critical darling championed by Roger Ebert, who named the film the best of that year. In his review, Ebert wrote, “If it is not nominated for Academy Awards, then the Academy is not paying attention. For the viewer, it is a reminder that sometimes films can venture into the realms of poetry and dreams.” Alas, the Academy was not paying attention, though the film received seven NAACP Image Award nominations, and Lemmons earned the Director’s Debut Award from the National Board of Review. And while Eve’s Bayou is a distinct film by a Black director about a uniquely Black experience, some critics at the time argued that it supplied a crossover experience between Black and white audiences because the subject matter wasn’t explicitly about race and ethnicity. “To hail Eve’s Bayou as the best African American film ever would be to understate its universal applicability to anyone on this plane,” wrote critic Andrew Sarris. But this attempt to downplay the film’s Black identity was in favor of aligning it with something more mainstream, meaning “white,” according to scholar Mia Mask in Cinéaste. Mask writes, “Just because Eve’s Bayou provides a picture of the Creole bourgeoisie doesn’t mean these people—or this film—cease to represent an African-American experience.” Rather, Mask and many other critics have since recognized the uniqueness of the film as an essential alternative to films by male directors and about urban Black communities.

One of the most successful independent films released in 1997, Eve’s Bayou earned the attention of audiences drawn to Black stories and the popularity of Samuel L. Jackson. The film was also a critical darling championed by Roger Ebert, who named the film the best of that year. In his review, Ebert wrote, “If it is not nominated for Academy Awards, then the Academy is not paying attention. For the viewer, it is a reminder that sometimes films can venture into the realms of poetry and dreams.” Alas, the Academy was not paying attention, though the film received seven NAACP Image Award nominations, and Lemmons earned the Director’s Debut Award from the National Board of Review. And while Eve’s Bayou is a distinct film by a Black director about a uniquely Black experience, some critics at the time argued that it supplied a crossover experience between Black and white audiences because the subject matter wasn’t explicitly about race and ethnicity. “To hail Eve’s Bayou as the best African American film ever would be to understate its universal applicability to anyone on this plane,” wrote critic Andrew Sarris. But this attempt to downplay the film’s Black identity was in favor of aligning it with something more mainstream, meaning “white,” according to scholar Mia Mask in Cinéaste. Mask writes, “Just because Eve’s Bayou provides a picture of the Creole bourgeoisie doesn’t mean these people—or this film—cease to represent an African-American experience.” Rather, Mask and many other critics have since recognized the uniqueness of the film as an essential alternative to films by male directors and about urban Black communities.

Critics and scholars gain little by placing this film into a categorical box. Eve’s Bayou maintains a celebrated legacy not as a crossover film for white audiences to appreciate Black cinema, but as a rich work by a Black female director who captured viewers’ attention with an intimate and haunting story, drawn from Lemmons’ childhood memories and fictionalized personal experiences. A fable about the implications of naïveté, the processing of complex social dynamics into adulthood, and the uncertainty between them, the film represents a questioning of assumptions about racial hegemonies both on and off the screen. However, what makes the film exceptional has nothing to do with its sociopolitical perspective; instead, it’s that the theme springs from a personal place for Lemmons, rooted in her childhood and family. And so, for its duration, the audience feels like the confidant of the adult Eve, listening to her tale of childhood tragedy in a manner that echoes how cinema has replaced the oral tradition of storytelling. The film remains so unforgettable because, by the end, nothing about the story feels settled in the mind of its protagonist. Eve’s family has secrets, raising questions with answers that will remain forever lost in time or inadequately remembered. Their stories will be passed down like myth, from one voice to another. Eve’s Bayou reminds us that memory is selective, and so is our past, sometimes in unresolvable ways.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on May 31, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Brown, Ann. “Bayou Spirits On-Screen.” American Visions, 12 (5), 1997.

Cho, Seongyong. “Haunting Magic: On ‘Eve’s Bayou,’ 20 Years Later.” 12 April 2017. https://www.rogerebert.com/far-flung-correspondents/haunting-magic-on-eves-bayou-20-years-later. Accessed 14 Oct. 2020.

Ebert, Roger. “Eve’s Bayou Movie Review and Film Summary (1997).” RogerEbert.com. 7 Nov. 1997. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/eves-bayou-1997. Accessed 14 Oct. 2020.

Ellison, Mary. “Echoes of Africa in ‘To Sleep with Anger’ and ‘Eve’s Bayou.’” African American Review, vol. 39, no. 1/2, 2005, pp. 213–229. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40033649. Accessed 15 Oct. 2020.

Gateward, Frances. “Eve’s Bayou.” Black Camera, vol. 13, no. 1, 1998, p. 7. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27761508. Accessed 15 Oct. 2020.

Helmsing, Mark. “Grotesque Stories, Desolate Voices: Encountering Histories and Geographies of Violence in Southern Gothic’s Haunted Mansions.” Counterpoints, vol. 434, 2014, pp. 316–323. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45177517. Accessed 21 May 2023.

Hobson, Janell. “Viewing in the Dark: Toward a Black Feminist Approach to Film.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 1/2, 2002, pp. 45–59. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40004636. Accessed 21 May 2023.

Mask, Mia L. “Eve’s Bayou: Too Good to Be a ‘Black’ Film?” Cinéaste, vol. 23, no. 4, 1998, pp. 26–27. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41689077. Accessed 15 Oct. 2020.

Stanley, Tarshia L. “The Three Faces in Eve’s Bayou: Recalling the Conjure Woman in Contemporary Black Cinema.” Folklore/Cinema: Popular Film as Vernacular Culture, edited by Sharon R. Sherman and Mikel J. Koven, University Press of Colorado, 2007, pp. 149–165. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgnbm.11. Accessed 21 May 2023.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review