The Definitives

Escape from New York

Essay by Brian Eggert |

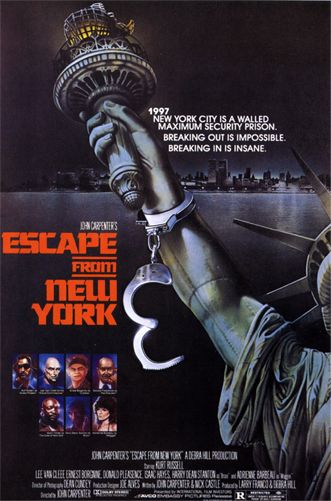

In 1981, New York City was not the beacon of hope and American unity post-9/11 society has raised it up to be; rather, violent urban dramas such as Death Wish (1974) and Taxi Driver (1976) reflected the city’s turbulence. Mob violence, street gangs, prostitution, rape, and drugs overwhelmed the troubled metropolis. Murder rates grew with each passing year. More than 120,000 robberies were committed that year, and over 2,100 murders. By comparison, there were only 328 murders in 2014. A mob-related trash strike left rotting waste on the streets, leaving refuse to fester and stink. During this year, John Carpenter released Escape from New York, an urban Western in which the island of Manhattan has been transformed into a maximum-security prison surrounded by 50-foot walls and mined bridges. New York City has always subsisted as a world unto itself, but Carpenter extends that idea into a frightening science-fiction concept. His film comments on how the New York of 1981 has isolated itself to such an extreme that walls, both metaphoric or literal, enclose its inhabitants within the crime-ridden sprawl, itself a symbol for all of America. In a bleak and nihilistic future, Carpenter explores a world in which the American Dream has failed, where the increasing crime rates never stopped and, according to the opening narration, in fact, quadrupled by 1988. In response, America becomes a fascist state and transforms New York into a penal colony. Carpenter’s unique dystopian future, set in 1997, exists on the verge of an apocalypse. And though the setting has been enclosed inside of New York Prison’s walls, it resembles many post-apocalyptic worlds to follow in cinema.

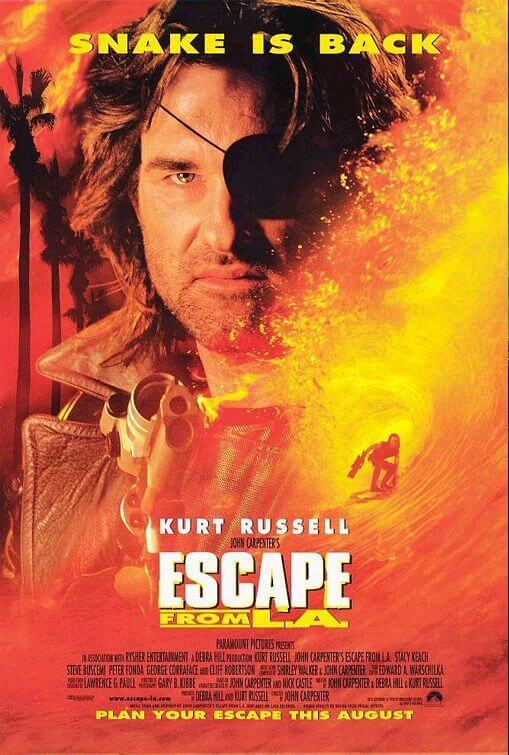

Rooted in American Westerns from Howard Hawks to Sergio Leone, Carpenter employs classical cinematic tropes later repurposed into qualities now often attributed to the post-apocalyptic subgenre. The director had already explored the concept of a city virtually overrun by crime with Assault on Precinct 13, his ostensible remake of Howard Hawks’ classic Rio Bravo (1958), the director’s longtime favorite. Carpenter’s 1976 release, about cops and criminals who band together in an abandoned precinct to fend off an onslaught of faceless Los Angeles gang members, seems to predict the arrival of Escape from New York. To be sure, it’s as though the L.A. gang continued to spread across the country, plaguing the nation until both a United States Police Force and New York Prison of Escape from New York were necessities. In the years following its release, the film was copied by several lowbrow Italian productions, which also borrowed heavily from George Miller’s Mad Max series: 2019, After the Fall of New York (1983), The New Barbarians (1983), Endgame (1983), and Rats: Night of Terror (1984), to name a few. More credibly, the film inspired William Gibson’s landmark cyberpunk novel Neuromancer. But on a broader scope, it can be argued that Escape from New York and its anti-hero Snake Plissken, played to steely badass perfection by Kurt Russell, have shaped almost every post-apocalyptic film to follow. Despite the comic-book fare Carpenter’s film later inspired, it bears the social awareness and cynicism that became the director’s signature over the years.

When the film opens, the American government has become imperialist and authoritarian. Those arriving at New York Prison have the option to “terminate and be cremated on the premises” rather than endure the prison, while those who try to escape face a 10-second warning before a helicopter blows them to smithereens. The story involves a radical Liberation Front overtaking Air Force One to deliver “a blow to this racist police state,” causing the plane to crash inside New York Prison, where the President (Donald Pleasance) lands in an escape pod. Besides the President himself, the MacGuffin is an audio cassette containing vital information the President must deliver to the Soviet Union and China in less than 24 hours. Hauk (Lee Van Cleef), the commander in charge of organizing a rescue, quickly learns the inmates of New York have taken the President captive in a bid to use him as a bargaining chip. Enter our anti-hero Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell), an eye-patched, highly decorated former U.S. Special Forces soldier who has since become an almost mythic criminal figure. Everyone has heard of Snake Plissken, both inside and outside of prison, and most of them have heard he was dead. Snake first appears in shackles, captured after an attempted robbery of a Federal Reserve Bank. Hauk arranges a deal with Snake—who he calls Plissken and is corrected, “Call me ‘Snake.'”—to rescue the President in exchange for a full pardon. Since he’s going in either way, Snake agrees to the impossible mission. He must land a glider on the World Trade Center, find the President and the vital cassette, and return within 24 hours. Also, Hauk has an insurance policy to prevent Snake from trying to escape on his own: two capsules injected into Snake’s carotid arteries that, unless neutralized by doctors under Hauk’s command, will detonate within the one-day time limit.

When the film opens, the American government has become imperialist and authoritarian. Those arriving at New York Prison have the option to “terminate and be cremated on the premises” rather than endure the prison, while those who try to escape face a 10-second warning before a helicopter blows them to smithereens. The story involves a radical Liberation Front overtaking Air Force One to deliver “a blow to this racist police state,” causing the plane to crash inside New York Prison, where the President (Donald Pleasance) lands in an escape pod. Besides the President himself, the MacGuffin is an audio cassette containing vital information the President must deliver to the Soviet Union and China in less than 24 hours. Hauk (Lee Van Cleef), the commander in charge of organizing a rescue, quickly learns the inmates of New York have taken the President captive in a bid to use him as a bargaining chip. Enter our anti-hero Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell), an eye-patched, highly decorated former U.S. Special Forces soldier who has since become an almost mythic criminal figure. Everyone has heard of Snake Plissken, both inside and outside of prison, and most of them have heard he was dead. Snake first appears in shackles, captured after an attempted robbery of a Federal Reserve Bank. Hauk arranges a deal with Snake—who he calls Plissken and is corrected, “Call me ‘Snake.'”—to rescue the President in exchange for a full pardon. Since he’s going in either way, Snake agrees to the impossible mission. He must land a glider on the World Trade Center, find the President and the vital cassette, and return within 24 hours. Also, Hauk has an insurance policy to prevent Snake from trying to escape on his own: two capsules injected into Snake’s carotid arteries that, unless neutralized by doctors under Hauk’s command, will detonate within the one-day time limit.

Properly incentivized, Snake lands in New York Prison and finds no trace of the President. Cabbie (Ernest Borgnine), a well-informed taxi driver inmate who’s partial to swing music cassettes, suggests that if the President survived, he would now be with “The Duke of New York”. But only one man knows where the Duke can be found, and that’s Brain (Harry Dean Stanton). Brain and his devoted sidekick Maggie (Adrienne Barbeau) agree to help rescue the President from the Duke (Isaac Hayes) in exchange for a way out of New York Prison. Their rescue goes awry, eventually leading to a chase on the mined 69th Street Bridge with Snake and his compatriots in Cabbie’s taxi, the Duke close behind in his Cadillac, and both racing toward the prison’s walls. Only the President and Snake make it to the wall, where Hauk’s men hoist the President to safety. The Duke arrives on foot and attacks Snake, but at the last moment the President guns down his former captor, ranting the Duke’s earlier taunts back at him (“A number one! You’re the Duke! You’re the Duke!”). Hauk keeps his word and neutralizes the explosives in Snake’s neck; he even grants the pardon, as promised. Meanwhile, as the President’s attendants busily prepare him to address the Soviet Union and China on television, he says if there’s anything Snake wants, he need only ask. Snake asks for a moment of the President’s time. “We did get you out,” says Snake. “But a lot of people died in the process. I just wondered how you felt about it.” Checking himself in the mirror, the President responds distracted, disinterested, as if feeding a line to the press: “Well, I want to thank them. This nation appreciates their sacrifice.” At this, Snake looks disappointed and walks away. The President begins his broadcast and plays the cassette. But instead of a top-secret formula, the speakers blast Cabbie’s copy of Les Elgart’s “Bandstand Boogie” from 1954. Snake has all but consigned the U.S. to doom, and as he exits the frame, he tears the magnetic tape from the real cassette and tosses it aside, just as he has done with his country.

Carpenter and Nick Castle wrote the first draft of this story in 1974, but their screenplay remained in the trunk until after the success of Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) and The Fog (1980). No studio would purchase what was ultimately a virulent reaction to the Watergate scandal. “The whole feeling of the nation was one of real cynicism about the President,” said Carpenter. “I wrote the screenplay and no studio wanted to make it… It was too violent, too scary, too weird.” After The Fog, distributors at Avco-Embassy Pictures agreed to release Carpenter’s next project, but he remained dissatisfied with his work on two scripts called The Philadelphia Experiment (made in 1984 by Stewart Raffill) and the still-unproduced “The Prometheus Crisis”. Searching for another option, Carpenter pulled out his script for Escape from New York and the studio gave him a green light. However, they wanted either Charles Bronson or Tommy Lee Jones to star as Snake Plissken. But Carpenter had already picked his leading man: Kurt Russell. In between his box-office performers Halloween and The Fog, Carpenter had shot the three-hour television movie Elvis, starring Russell; the former Disney child star played the King himself in a quite convincing and much-acclaimed performance (he later played Elvis’ voice in Forrest Gump (1994) and an Elvis impersonator in 3,000 Miles to Graceland (2001)). The director and actor remained friends, as both men approached their field with a devotion to story and narrative “without pretensions” and “no bullshit”. And when Russell had expressed his interest in shedding his former persona, Carpenter was more than happy to abide.

Carpenter and Nick Castle wrote the first draft of this story in 1974, but their screenplay remained in the trunk until after the success of Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) and The Fog (1980). No studio would purchase what was ultimately a virulent reaction to the Watergate scandal. “The whole feeling of the nation was one of real cynicism about the President,” said Carpenter. “I wrote the screenplay and no studio wanted to make it… It was too violent, too scary, too weird.” After The Fog, distributors at Avco-Embassy Pictures agreed to release Carpenter’s next project, but he remained dissatisfied with his work on two scripts called The Philadelphia Experiment (made in 1984 by Stewart Raffill) and the still-unproduced “The Prometheus Crisis”. Searching for another option, Carpenter pulled out his script for Escape from New York and the studio gave him a green light. However, they wanted either Charles Bronson or Tommy Lee Jones to star as Snake Plissken. But Carpenter had already picked his leading man: Kurt Russell. In between his box-office performers Halloween and The Fog, Carpenter had shot the three-hour television movie Elvis, starring Russell; the former Disney child star played the King himself in a quite convincing and much-acclaimed performance (he later played Elvis’ voice in Forrest Gump (1994) and an Elvis impersonator in 3,000 Miles to Graceland (2001)). The director and actor remained friends, as both men approached their field with a devotion to story and narrative “without pretensions” and “no bullshit”. And when Russell had expressed his interest in shedding his former persona, Carpenter was more than happy to abide.

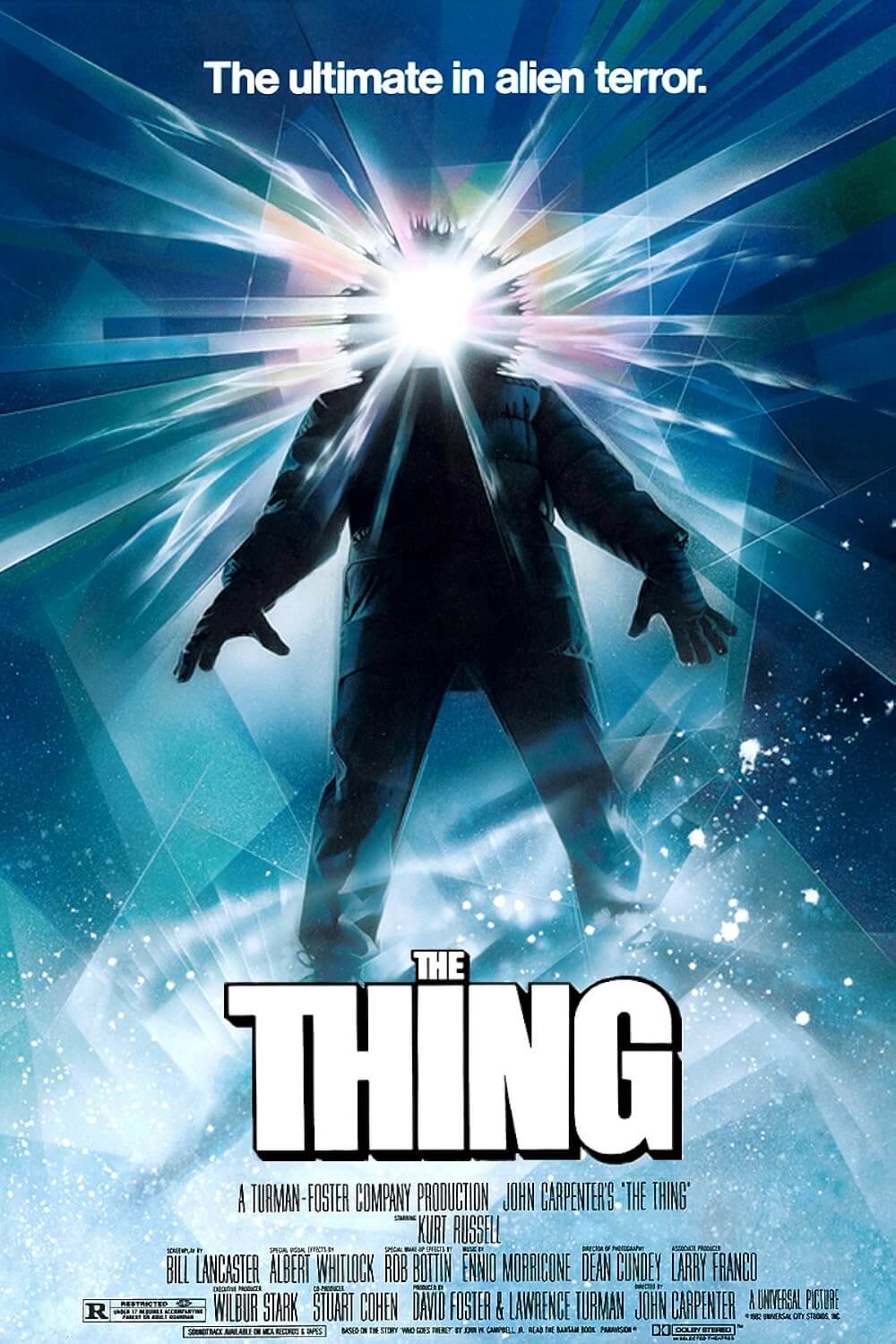

For Escape from New York‘s technical crew, Carpenter reteamed with several essential behind-the-scenes collaborators that made the film a technical wonder. His producer Debra Hill and co-producer/assistant director Larry J. Franco joined. He once again hired Dean Cudney, who shot Halloween and The Fog, as director of photography. Famous for his brooding master shots and smooth, measured camera movements, Cudney also designed the film’s dirty, post-apocalyptic look and saturated the image with blue hues (this was before the days of digital color timing). Cudney worked alongside Carpenter again on The Thing (1982) and Big Trouble in Little China (1986), although he soon moved on to work with Robert Zemeckis on several films (including the Back to the Future trilogy) and Steven Spielberg on Jurassic Park (1993). Responsible for the gritty look of the New York sets and city streets was Jaws (1975) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) production designer Joe Alves, who insisted that Carpenter shoot on actual city streets instead of a studio backlot. Location manager Barry Bernardi found East St. Louis, Illinois, which contained whole neighborhoods burned-out and abandoned after a disastrous 1976 fire. The choice proved essential for the film’s mise-en-scène, as the audience never doubts the authenticity of the ruined streets, seedy interiors, or squalid air contained within the frame. For the percussive electronic music, Carpenter composed alongside Alan Howarth, who later served as an Academy Award-winning sound designer on some of the biggest blockbusters of the 1980s, including Raiders of the Lost Ark (1982) and the Star Trek series.

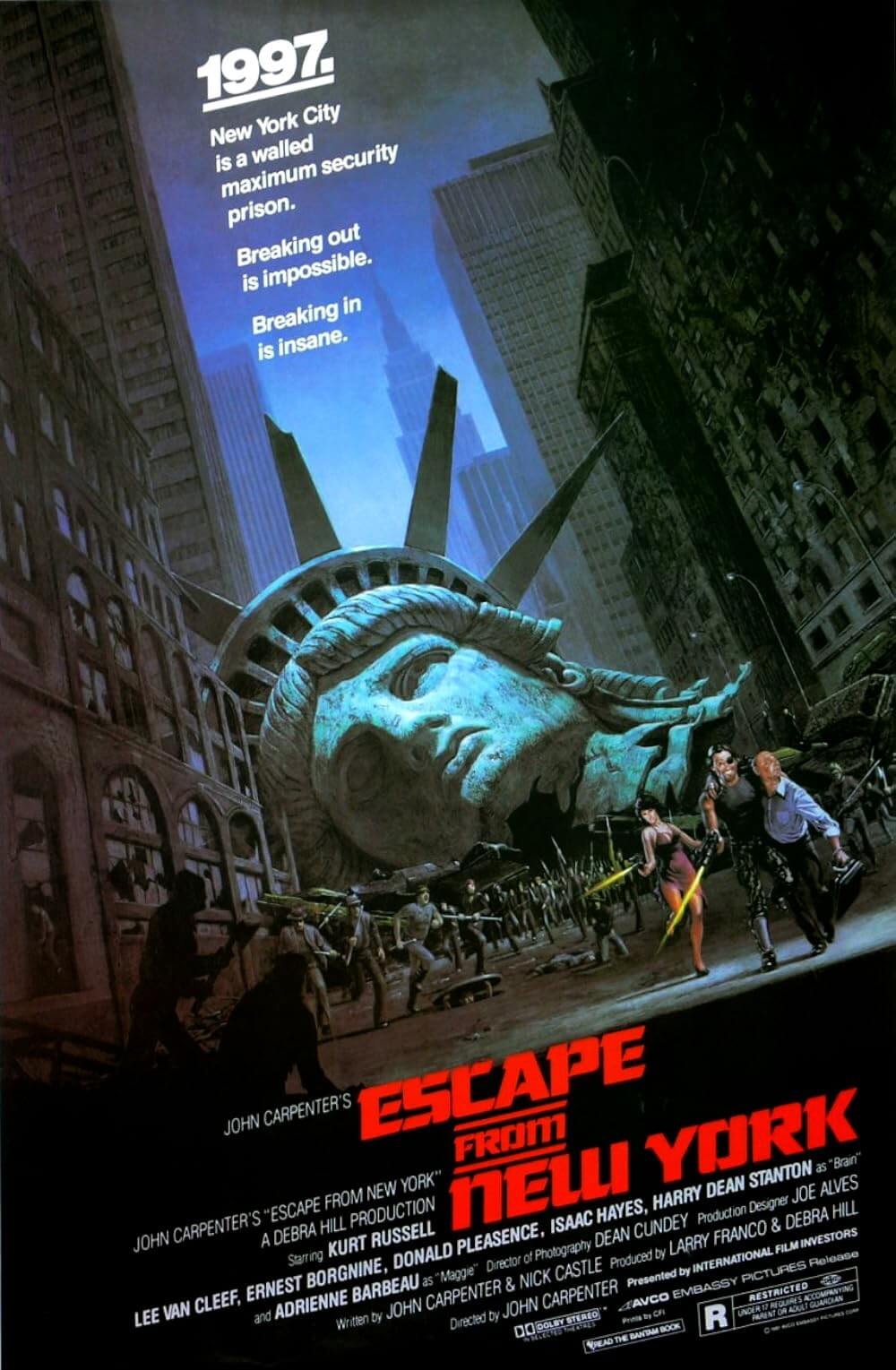

What works so well about Escape from New York is Carpenter’s momentum, maintained throughout because the plot consists of a series of escapes: When Snake cannot find the President at first, his brief pause is interrupted by an invasion of under-dwelling “crazies”. He must escape capture when he’s detained and forced into a death match by the Duke at Madison Square Garden. He evades the Duke’s men atop the World Trade Center, and again across the 69th Street Bridge. And, of course, Snake must escape the prison altogether, and in essence, must escape the confines of his imposed time limit clicking away on his red digital wristband. Carpenter designed Escape from New York as an “Aristotelian” dramatic scenario wherein time, place, and action interconnect within confined quarters, all closely tied to the setting. He uses the aforementioned New York landmarks and writes a mock-Broadway show tune “Everyone’s Coming to New York” as a lark. Even the film’s poster adopts the Statue of Liberty’s fallen head, an instantly shocking image not used in the film. More specifically, Carpenter once again drew from Hawks, who used the notion of time in several tense motion pictures, among them Rio Bravo. However, like Rio Bravo, the characters in Assault on Precinct 13 and The Fog want time to pass faster to make their respective threats disperse, whereas Carpenter’s use of time in Escape from New York contradicted the Hawksian method and proved more innovative, in that Snake’s time is limited and he needs more of it. The President must present his vital information before an international summit ends, and Snake must find him before his time runs out and the explosive capsules detonate in his neck.

Snake Plissken endures as an iconic anti-hero because he embodies a human myth, someone whose legend has been cemented in the criminal underworld, yet he remains fallible. Snake is not an invincible superhero; after all, he was caught and sentenced to a maximum-security prison. As a deleted scene (a sequence rejected by prescreening audiences and removed) from the original opening shows, Snake was originally captured during a botched robbery. He’s again outwitted by Hauk when a doctor injects the explosive capsules into his neck; he’s shot with an arrow in the leg and limps for the second half of the film; and he checks his remaining time on the mined bridge when he should be watching the road, resulting in an explosion and the death of Cabbie. Snake makes mistakes; as such, his status as an anti-hero remains justified. Moreover, he could hardly be described as a moralist. Snake is anti-everything, a rebel without a cause. At one memorable point in the film, he sees three men about to rape a tired and beaten woman; rather than help, he continues moving. It’s not his business. Russell once remarked that Snake’s only concern is “the next 60 seconds. Living for exactly that next minute is all there is.” Indeed, Snake is a survivor. Because he has survived so long, his legend endures. Only in the finale does the audience see any kind of devotion to another character. When Maggie freezes after Brain dies from a bridge mine, Snake pleads with her to keep moving. She refuses and determines to stay back with a gun and get vengeance, knowing it means death. Snake respects this and tosses her his last weapon. The two characters share an unspoken understanding, the kind of Hawksian bond formed between men with a single look in Rio Bravo.

Russell plays Snake as a combination of Clint Eastwood’s more mythic, nameless, and almost certainly supernatural characters from High Plains Drifter (1973) and Pale Rider (1985), although he’s more often associated with Leone’s ‘The Man with No Name’ trilogy, perhaps because the latter two entries in that trilogy also starred Van Cleef. The association links Van Cleef’s sociopathic character Angel Eyes with Eastwood’s Blondie, here represented by Snake. The relationship between the two not only transcends films but extends to the analogous, often respectful rapport of predator and prey, the mortal enemies Van Cleef and Eastwood played opposite each other in For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). Nevertheless, the relationship between Snake and Hauk remains more complicated. On opposing sides, Russell and Van Cleef have an unspoken admiration for one another; both are professionals and both see the hypocrisy of their country. But Hauk enjoys his authority and power. Consider how he does not initially tell Snake about the explosive capsules, that the administering doctor has to prompt him—Hauk would have rather preserved that power until the opportune moment. Snake rejects everything such power represents. “I thought you were dead,” someone in the prison remarks. “I am,” Snake replies, dead because he had sold out and now once again carries out a mission for a government in which he no longer believes. As such, anyone who believes in or even lives in this country is as good as dead, so what does it matter?

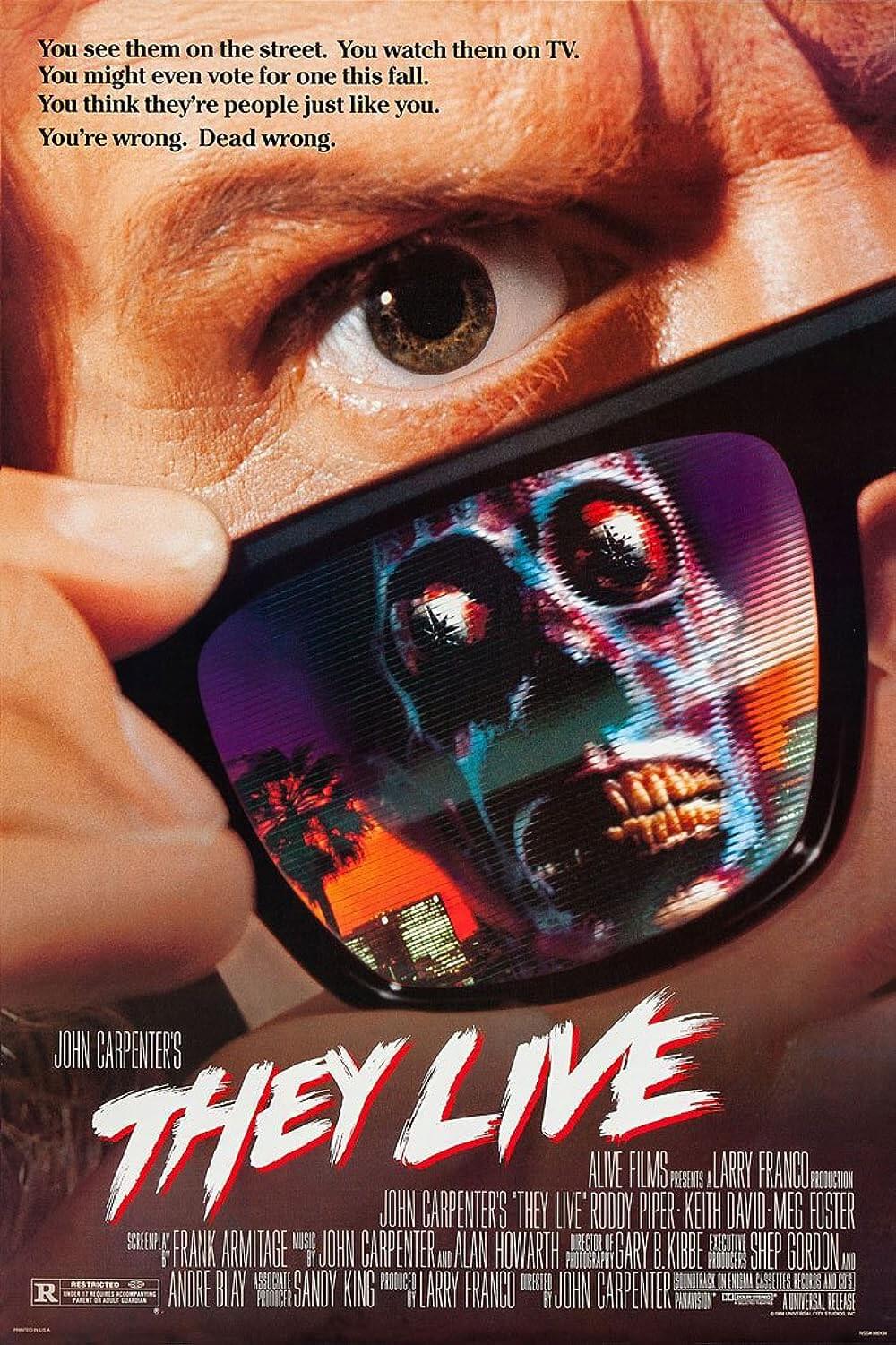

New York Prison mirrors Snake, or perhaps they are both products of their society. The prison is a cold, lonely place devoid of hope and contained within rigid barriers. Snake could be described the same way, as could most of the characters within the film. Aside from Maggie’s affection for Brain, there’s almost no evidence of loyalty or friendship between anyone. Everyone is out for themselves. And yet, the main characters follow a precise code of honor, namely Snake, Maggie, and Hauk. Like many of Carpenter’s leading men from The Thing to They Live, the characters in Escape from New York are self-made—and more than just Snake. Brain was originally “Harold Hellman” but renamed himself once inside; Cabbie defines himself by his occupation, his pride in knowing New York’s streets; doubtful Maggie’s real name is Maggie; and the Duke has created his entire image as larger-than-life, the “A-number-one” figurehead, complete with chandeliers mounted on the hood of his Cadillac. Because they each live in a world they would describe as not their own, they must deny their true identities and redefine themselves with new names. For this reason, when Hauk first addresses Snake as “Plissken” on Liberty Island at the beginning of the film, Snake corrects him: “Call me Snake.” After Snake returns and earns his freedom, he sabotages the President and no doubt incites the downfall of the American fascist regime. Only then, when Hauk finally addresses him as “Snake” can our hero reply, “Call me Plissken,” because the world will soon transform into one of his own making.

In addition to those already discussed, such as self-made men, Carpenter utilizes a number of Hawksian traits: the morally certain hero unwilling to compromise his ideals; a tough but sexy female lead; a woman in action and in danger, but not in distress; a whole gang of anonymous bad guys led by a single leader, with a single right-hand man (the hissing Romero, played by Frank Doubleday); and a “ragtag” team of professionals. Snake’s recurrent line “Got a smoke?” is asked of allies and enemies alike, not unlike Dean Martin’s character in Rio Bravo. Carpenter’s major derivation is Maggie’s fate because, by all accounts, she should be Snake’s romantic interest—she’s as hardened and as devoted to her principles as Snake. But her convictions ultimately spell out her end, which signals a dreary, if admirable Carpenterism. Another cynical moment early on features Season Hubley as a woman trapped inside the city; just before she kisses a willing Snake, she’s pulled into the ground by a band of crazies. Indeed, Snake isn’t the kind of hero who “gets the girl”. Buried underneath the surface of such qualities resides another, less discernable Hawksian trait: the degree to which Escape from New York is also a fun piece of entertainment. In spite of the dire situation and hopeless surroundings, Escape from New York is not without its sense of humor, however macabre. The film contains a dark, barren-dry wit just under the surface of its commentary. Such touches might be shown in the form of Barbeau’s eye-rolls or Russell’s sarcastic tone, Brain’s slimy wheeling-dealing or Cabbie’s enthusiasm. The final gag comes in one of the last shots, where Cabbie’s cassette of “Bandstand Boogie” plays in place of the President’s planned broadcast, signaling America’s end with a bit of swing. This brief moment of comic absurdity in the end represents the most accessible moment in the film, which Carpenter saturated with other-worldly performances and a deliberate distance.

Looking back at the film’s events in a 1997 future, viewers might scoff that the year came and went without Carpenter’s prediction coming to pass, just as scholars used the relatively uneventful passing of 1984 to discredit George Orwell’s predictions. Of course, if Carpenter and Orwell had not dated their future, the material may have proved timeless to a greater degree; however, by assigning a date to impending doom, both stimulate a thought process that forced its contemporary viewer or reader to consider how, if nothing about their society changes, then-modern ways of living might mutate into the horrific vision presented as art or entertainment. Dwelling on the specific year and the failure of the artist to foresee with any accuracy how said year will look is a pointless exercise; instead, consider how, historically speaking, such a future seemed quite plausible at the time of its creation. Orwell and Carpenter were less interested in prophecy than in metaphor. Carpenter’s assessment of New York, and by extension America as a whole, categorizes the country as a crime-ridden prison from which there is no escape. It could hardly be a coincidence that Carpenter chose two bald men to represent the powers on opposing sides, one an overweight white-collar dictator, the other an urban stereotype. After all, the government and the Duke have the same level of authoritarian control over and devotion from their respective hordes; in that sense, the Duke and the President are much the same kinds of evil.

Regardless of how much John Carpenter pays homage to Howard Hawks, or how much Kurt Russell’s performance is rooted in Clint Eastwood’s various onscreen characters, Escape from New York stands on its own merits and achieves something unique. Because of its particular subgenre and embrace of the post-apocalyptic realm, it has been branded a cult film—a label that comes with its own negative or limiting associations, along with the unfortunate tendency for critics and scholars to avoid taking the film seriously as great cinema. Unlike later, similarly themed Carpenter films such as Ghosts of Mars (2001), an enjoyable trifle, Escape from New York works on multiple levels and comes from a very reactionary place inside Carpenter. There’s a passion behind it and behind the camera a filmmaker who sees the American Dream as long since dead. Carpenter would grow increasingly disenchanted over the years, with those feelings extending to Hollywood and leading to his eventual, unofficial retirement. This film represents a filmmaker in his prime, driven by his most potent beliefs to tell an exciting story. A fantastic and enduring escape itself, whether it’s meant to have taken place twenty years from now or twenty years in the past, Escape from New York remains a clever satire of his contemporary worldview and enduring evidence of Carpenter’s skill as an artist and entertainer.

(Edited June 18, 2017)

Bibliography:

Boulenger, Gilles. John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness. Spakenburg : H.O.M. Vision, 2002.

Cumbow, Robert C. Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc.; Second Edition, 2000.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review