The Definitives

Duck Soup (1933)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

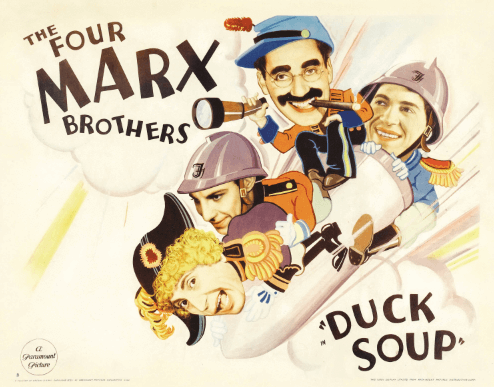

Most Marx Brothers comedies suffer from the same problem. They contain passing moments of hilarity tied together by an obligatory story. Every pun, double-entendre, non-sequitur, witticism, and wordplay; every conceivable trick of language; every sight gag, funny face, sleight of hand, and display of slapstick—they are all connected by the most inconsequential of narrative tissues. But none of the customary padding mires Duck Soup, their best and purest film. It forgoes the subplots and extraneous material that bloats each of their other titles, most of which limit the Marx Brothers to mere supporting players in a film otherwise structured around a tedious story and runtime. Barely feature-length, Duck Soup runs just over an hour. The 1933 comedy is like a fine reduction of their zany, cartoonish style—in fact, most Looney Tunes borrow from the Marxes—whereas the humor in their other screen appearances has been watered down. If there ever were shreds of romance or intrigue in the story, they have been snipped out, leaving only the good bits. It was made by Leo McCarey, the only distinct filmmaker ever to direct a Marx Brothers comedy. Perhaps because of McCarey’s ability to get to the essence of his material, Duck Soup feels charged in its tale of Freedonia, a struggling and desperate country that, in its hour of need, turns to Groucho’s cockeyed madman for help. Many critics and scholars have linked the story to Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini; today, another figure comes to mind. In any case, the 1933 comedy roots into the false pageantry, pretense, and grandstanding behind politics and war, exposing the madness for what it is.

From the outset, Duck Soup seems off its rocker. The opening frames transition into the studio’s logo that reads “A Paramount Picture” against the iconic mountain, until the word “Presents” appears, leaving the title to read, “A Paramount Presents Picture.” That doesn’t sound right, does it? Then the title card appears atop an image of ducks swimming in a pot of water over a fire; they don’t know it yet, but they’re being boiled alive. But the title does not mean a literal duck soup. In my half-Polish household as a child, duck soup, also called Czarnina, meant a rare delicacy that I would not taste. It meant my father came home from a farm with a jar of blood from a freshly killed duck. Sometimes he wouldn’t make the soup for a day or two, and the jar of blood would sit in the refrigerator between the milk and orange juice. The Marx Brothers were not Polish; their Jewish parents had roots in Germany and France. No, duck soup was a phrase coined in 1902 meaning a simple or effortless task, such as shooting ducks in a barrel, thus making duck soup. Groucho’s explanation, predictably, made less sense: “Take two turkeys, one goose, four cabbages, but no duck, and mix them together. After one taste, you’ll duck soup for the rest of your life.” Instead, the title refers to the ease in which Groucho’s Rufus T. Firefly takes over the bankrupt nation of Freedonia. When everyone’s scrambling and divided, Firefly comes to the rescue and, by the end, tosses the same fruit at his supporters as he does at his enemy.

Duck Soup remains one of the Marx Brothers’ most celebrated comedies alongside Animal Crackers (1930) and A Night at the Opera (1935), though everyone has their own favorite Marx comedy. The American Film Institute put it on their lists of the best and funniest movies. The Library of Congress included it in the National Film Registry in 1990. Comedians ranging from Woody Allen to Sacha Baron Cohen have drawn from it, while critics such as Roger Ebert and Leonard Maltin have showered it with praise. Although a few things are true of every other Marx Brothers film—Harpo plays the harp, Chico plays the piano, Zeppo plays the background, and Groucho plays everyone else—Duck Soup breaks the mold. The audience does not need to suffer through another one of Chico or Harpo’s instrumental recitals (impressive as they are), but Harpo plucks a few piano strings at one point. Usually Zeppo finds himself entangled in an obligatory subplot; not so here. The film avoids filler and artificial sweeteners. The comedy is Grade A, naturally sourced, Certified Organic, Non-GMO, and purely derived. The plot, if one can call it that, is little more than comedic bits strung together by the thinnest tissue. Some consider that to be one of the film’s many faults. Irving Thalberg, head of production at MGM, used Duck Soup as a platform to work against. He wanted someone the audience could sympathize with in every Marx Brothers comedy, and after the film, their work became bogged down with story. But if there’s just one title that gets to the essence of the Marx Brothers and their brand of comedy, it’s Duck Soup.

To appreciate the film as a cinematic distilment of the Marx Brothers’ comedic style, some background is required to demonstrate how they arrived in Hollywood and remained tenuously connected to their vaudeville routine before committing to the film medium. The Marx Brothers arrived in Hollywood in 1929, after twenty years of performing on vaudeville stages around the United States, including on Broadway, to film their stage show The Cocoanuts for Paramount Pictures. Groucho, then going by his original name, Julius, made his stage debut in 1905 at the age of fifteen. He was the middle of five children; his mother, Minnie, became a stage impresario by pushing her boys to perform together. Over the next few years, Minnie added her sons Milton and Adolf, who went by Gummo and Harpo, to the act. The oldest child, Leonard, later known as Chico (pronounced Chicko not Cheeko), gave up his solo career in a piano act to join his brothers on stage. Though they toured together in this foursome for years, Milton, feeling a tinge of patriotism, left the troupe and went off to the First World War, leaving Minnie to replace him with her youngest, Herbert, who went by Zeppo. Across the Midwest, the “Four Marx Brothers” pushed buttons and sometimes clashed with monopolistic stage owners who kept a sharp eye on their performers and banned anyone who broke the rules. When the boys tested their theater owners by improvising material, Minnie would keep them in line. She would shout “Greenbaum”—the name of their mortgage lender—from the audience when they improvised too much. When their act inevitably pushed the wrong buttons and got them banned from theaters on the road, their vaudeville routine landed on Broadway in 1924, where they performed the bawdy musical I’ll Say She Is. They were a sensation. The next year, their show The Cocoanuts debuted, followed by Animal Crackers in 1928.

In 1927, Warner Bros. debuted the first talking motion picture, The Jazz Singer, an adaptation of Al Jolson’s hit Broadway show, at the studio’s Times Square theater. Hollywood would never be the same. Though some believed “Talkies” were just a fad, most studios scrambled to adjust to the new exhibition standards. Given that some silent film actors would not survive the transition to sound, the studios signed contracts with popular stage performers who could recite lines and sing; they also purchased the rights to Broadway musicals that could be adapted to the screen. Paramount, once the home of silent film comedians from Buster Keaton to Harold Lloyd, signed a deal with the Marx Brothers to shoot The Cocoanuts in their Astoria studio in New York. Uncertain of whether they should commit to the film medium, the brothers shot at the studio by day but maintained their stage performances at night. By this time, most of the brothers were either in or approaching their forties, and the resulting schedule left them exhausted. Their eventual film was a huge box-office hit, though it shows evidence of the filmmakers still trying to figure out the sound apparatus—muffled dialogue and ear-piercing, tinny musical numbers. The success of The Cocoanuts led to another stage-to-film adaptation, Animal Crackers in 1930. By this time, Minnie had died, and the Marx Brothers had seen the writing on the wall. Ticket sales to their stage shows were dwindling. Talkies had taken over. They were Hollywood bound.

Still, some of the Marx Brothers were hesitant about committing to Hollywood. Harpo considered leaving the group after Minnie’s death, having a successful backup plan in the realty market. Zeppo, the least effectual and passive straight man of the foursome, also thought about leaving. He was all too aware that the stage shows and movies gave him little to do; he was tired of having few lines and playing the romantic lead, and he regularly thought about finding his own path. Even Groucho refused to buy property in Tinsel Town at first, fearing that their presence on the silver screen might not last beyond their newly signed three-picture deal with Paramount, which would include their next two movies, Monkey Business (1931) and Horse Feathers (1931). Most of the brothers had good reason to worry about their future in Hollywood. The stock market crash that led to the Great Depression had left them financially compromised. Groucho lost everything when the market tanked. Chico was broke as well, mostly on account of his lifelong gambling addiction. Most industries were failing around the country. A quarter of all Americans were out of work, and the government offered little reprieve. Hollywood was struggling too. Movie theater attendance was down, even though many found an escape from their bleak reality inside the cinema. People waited for hours in bread lines, but “we were the toast of the town,” Groucho wrote. In a world where people needed a laugh, the Marx Brothers had been consistent moneymakers for Paramount. Still, the brothers resolved to sign a deal with RKO for a stage tour on the vaudeville circuit; since each of their pictures with Paramount wrapped shooting in a few short weeks, their stage performances could bring some financial stability in uncertain times.

Their last film under the three-picture deal with Paramount was initially called Firecrackers, then Cracked Ice, but its development had been met with some shady moves by the struggling studio. The Marxes had signed their initial deal with Paramount Publix Corporation; however, the studio sought to transfer the contract to a new company called Paramount Productions. Following other talent that had raised questions about legality of the studio’s questionable contract finagling, the brothers canceled their agreement with Paramount. They sought to make a deal with producer Sam Katz, who convinced them to make five pictures under his independent production company. Katz’s financing fell through and left the brothers twisting in the wind. If nothing else could be learned from these contract disputes and new offers, it was that the Marxes were in high demand. They resolved to make one final picture with Paramount, not as part of their previous three-picture deal with the studio, but a new one-picture contract to shoot Cracked Ice, whose name had been changed to Duck Soup. Shortly before signing with Paramount for Duck Soup, their father, Sam “Frenchy” Marx, a stage performer and the family’s co-manager alongside the late Minnie, died. The moment marked a turning point for the brothers. It meant that their vaudeville days were behind them; Hollywood was the future. Frenchy’s death also meant that Zeppo felt no pressure from his parents to continue working with his brothers. After Duck Soup, the Marx Brothers would be a trio.

Not that Zeppo was ever a crucial component to the group. Some have argued that his presence brought a measure of sanity to the otherwise insane personalities in the Marx Brothers’ films at Paramount. Groucho, the curmudgeon whose wit headed the group, also sings, moves like rubber, and acts as the wise guy. Groucho is a wordsmithing comedian for the era of Talkies, just as Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton were the best physical comedians of the silent era. Chico’s thick-headedness is part of his sly con-man persona, with his broken faux-Italian accent and confounding wordplays like the “Why a Duck?” sequence from The Cocoanuts. He can talk anyone into or out of anything, and he’s the only brother who can outwit Groucho. Harpo’s purely visual pantomime, combined with his unhindered impulses, make him an unstable force among agents of chaos. If he speaks, he does so with a horn. Perhaps that’s why he is a favorite among children; there’s a sweetness and innocence to him too. He might also be thoroughly batty with equal parts devil and angel compelling him. Groucho, Harpo, and Chico have been compared to ego, superego, and id. Elsewhere, they have been more aptly described as the brains, the heart, and the hands. Zeppo, meanwhile—not to mix metaphors—is the fourth wheel on a tricycle. If Groucho’s character needs an assistant or a young woman needs romancing, Zeppo occupies that role in the early Paramount films, usually in the background and with as few lines as possible. After Zeppo left the group, when the remaining threesome signed a deal with Irving Thalberg at MGM for five more pictures, his role was often played by some other nondescript actor—for instance, Allan Jones occupies the straight man role in A Night at the Opera, the Marx Brothers’ first comedy at MGM.

Then again, most of the Marx Brothers comedies at MGM would be sedated by Thalberg, who sought to tame the wild beast with romantic subplots that distracted from the zany appeal of the brothers. Perhaps that’s why their output at Paramount, most of it drawn from their vaudeville shows, feels somewhat dangerous. By contrast, their MGM films are nicer; they operate at a measured clip and space out the jokes for easy consumption. Duck Soup never slows down. It respects the audience enough not to and assumes we’re smart enough to keep up. The earlier Paramount films seem ad-libbed and unbridled, even though most of the material had been performed as written. The brothers perfected their routines on the stage, rewriting after every show like whittling a spear out of a tree trunk. For instance, Harpo started giving people his leg to hold on the vaudeville stage, and the bit stuck. Their comedy was a well-oiled machine, the name of which would probably sound like something constructed by Dr. Seuss (a Zippy-Doo Chuckle Sputterer). And yet, because of its political nature, there’s also a macabre undercurrent to Duck Soup. When Rufus T. Firefly addresses his new regime, he lays down the law in the song “Laws of My Administration,” singing: “If any form of pleasure is exhibited, report to me, and it will be prohibited.” Then he casually evokes a nursery rhyme to explain what happens when someone disobeys his rule: “We stand him up against the wall and pop goes the weasel.”

Maybe now is a good time to describe the plot of Duck Soup. It entails the fate of Freedonia, a bankrupt country on the verge of collapse. Its politicians ask wealthy widow Mrs. Gloria Teasdale (played by the so-called Fifth Marx Sibling, Margaret Dumont, a haughty straight woman whose presence always shows a twinkle of bemusement) for $20 million to save the country. She refuses to lend anything unless the government installs a new leader, Rufus T. Firefly (Groucho). How Teasdale came to trust Firefly with the fate of her country, who can be sure? When Firefly arrives, he carries a cigar instead of a sword or scepter, a self-deprecating symbol of Groucho’s openly diminutive sexual prowess. He has no plan for the future of Freedonia, but if his introductory song “Laws of My Administration” indicates anything, it’s that he’s in charge. Meanwhile, Ambassador Trentino of Sylvania (Louis Calhern), a crooked politician if ever there was one (there was), has a spy working in Freedonia: Miss Vera Marcal (Raquel Torres), who seems to have a romantic tryst with Firefly’s assistant, the dully named Bob Roland (Zeppo). Trentino has also hired Chicolini and Pinky (Chico and Harpo) to infiltrate Freedonia, not that they get much done besides tormenting the lemonade vendor (Edgar Kennedy) into a state of near-insanity. Before long, Firefly exposes the spies, enlists them for Freedonia, and declares war against Sylvania. Only after pelting Trentino with fruit do the Marx Brothers convince Sylvania to surrender.

Despite what the credits say about Duck Soup’s screenplay, the production was a collaborative effort. The script is credited to Bert Kalmar and his partner, Harry Ruby, who wrote the music and lyrics to several Marx Brothers comedies; Arthur Sheekman and Nat Perrin contributed additional dialogue. The brothers, of course, worked on their own bits. Producer Herman Mankiewicz (later of Citizen Kane), who would be fired from the picture, also supplied input. Arguably the most significant influence on the end result is Leo McCarey, whose experience making Laurel and Hardy comedies (including a 1927 short called Duck Soup, no relation) under Hal Roach and working alongside legends like W.C. Fields prepared him for the task. McCarey, who would go on to direct Harold Lloyd in The Milky Way (1936) and Cary Grant in The Awful Truth (1937), contained a streak of “closet authoritarianism” according to critic Charles Silver. He took filmmaking and storytelling seriously, and he labored over his craft. Jean Renoir would later say that McCarey understands people “better perhaps than anyone else in Hollywood.” Renoir was no doubt referring to McCarey’s dramatic work on his Depression-era masterpiece, Make Way for Tomorrow (1937), but McCarey’s ability to get to the essence of people is true of the Marx Brothers as well. Even so, he wanted nothing to do with the unpredictable Marx Brothers and planned to leave Paramount when the studio suggested him for their next film. But then the brothers left briefly, so McCarey stayed, only to be contractually obligated to direct Duck Soup when the brothers returned. “The most surprising thing about this film,” the director remarked later, “was that I succeeded in not going crazy. I really did not want to work with them: they were completely mad.”

Even so, McCarey understands what makes the Marx Brothers tick. He may think their antics are insane, but he knows how to use the cinematic apparatus to best frame their strengths as performers. The director keeps the songs to a minimum, unless they are played for laughs; however, he replaces music with an editing style that creates a crucial tempo in Duck Soup. When you watch earlier films like The Cocoanuts or Animal Crackers, the filmmakers are content with recreating the stagey, vaudeville experience with a camera that remains unmoving, allowing entire skits and songs to play out, usually in a single, stationary medium shot. Alternatively, in an interview at the American Film Institute, McCarey told Peter Bogdonavich that he structured the film around “the ineluctability of incidents. The idea is that if something happens, some other thing inevitably flows from it.” In other words, things just sort of unfold in Duck Soup and they don’t necessarily amount to a plot, and McCarey follows what happens with a roving camera and sharp editing. During the “This Country’s Going to War” number, the editing follows the tempo, reflecting the contagious group silliness that ends with everyone falling to their knees and writhing around the floor. The sequence borders on surreality. So does the battle sequence in the finale, where Groucho’s uniforms alternate between cuts from a Confederate soldier to a Boy Scout to Davy Crockett. McCarey’s willingness to break with the laws of reality would make him the Marx Brothers’ greatest director.

In his monograph about the film, Roy Blount, Jr. writes that Duck Soup was believed to be “too funny for its own good” by Paramount. But it was not a flop as Groucho later claimed in interviews and his autobiography; it made the studio major box-office numbers throughout 1934, just not the returns seen by the Marx Brothers’ earlier comedies. Critics at the time found it tasteless and tedious; they used its perceived failure to explain why the Marxes briefly flirted with giving up Hollywood in 1933. The critic in the Los Angeles Times wrote, “Every indication points to the Marx Brothers’ being through with the movies for the time being,” and Groucho had indicated as much in interviews from the period. Other critics did not appreciate the madcap pacing and joke-machine structure of the film. Mordaunt Hall, writing for The New York Times, called Duck Soup, “for the most part, extremely noisy without being nearly as mirthful as their other films.” The response is not unexpected; much about the Marx Brothers and Duck Soup in particular flies in the face of conventions, both in the 1930s and today. The sheer relentlessness of the humor leaves nothing to gloss over, no perfect moment to get a snack or use the restroom. There’s barely time enough to laugh and hear the next joke. It operates at three-hundred miles an hour, and it does not slow down until the end credits. Most of their films have a few moments of greatness and a few scenes the viewer could do without, but most of the fat has been trimmed from Duck Soup. Then again, today we might wish that Harpo did not adopt a Pepe Le Pew treatment of women, while the spoof of minstrel songs (“All God’s chillun got guns”) and a racial epithet used in the film remind us how much representation has changed for the better.

Still, for this avid cartoon-watcher, the easiest comparison to the Marx Brothers’ presence in Duck Soup is Bugs Bunny, whose Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies shorts would often subvert reality in hilarious ways. Of course, Bugs would not arrive on the scene until several years after this film, but the Marxes had a clear relationship with what Tom Kenny calls “the laws of the cartoon universe.” Many of the writers on Animal Crackers, for example, had worked as cartoonists, injecting a non-stop style of comedic mayhem into the Marx Brothers’ work—while also creating a chicken-and-the-egg conundrum. Somewhere in the primordial soup of vaudeville, cartoons, and Marx Brothers cinema, a style of humor was born. Nevertheless, the difference was that most cartoon shorts of the 1940s and 1950s lasted a few minutes, during which Bugs Bunny or Daffy Duck could break any number of rules in their ten-gags-a-minute style. Duck Soup sustains the same momentum for 68 minutes; one of the Marxes is always up to something—sometimes all at once. Meanwhile, their frenzied behavior drives some poor sap up the wall, here represented by Calhern, Dumont, and Kennedy. Harpo and his eager scissors snip Calhern’s coattails; Chico and Harpo alternate hats with Kennedy; and Groucho, breaking the Fourth Wall, remarks about Dumont’s affections: “Already she’s making advances.” Like Bugs, there’s a meta quality to Groucho, whose eyes roll in different directions; he keeps one of them bemused and the other sharing his amusement with the audience—as though he’s both inside and outside of the film.

Arguably the most famous scene from Duck Soup is the mirror routine, which has been copied and, well, mirrored countless times since. It begins when Harpo’s Pinky disguises himself like Groucho’s Firefly to sneak into Mrs. Teasdale’s room. The other Marxes often dressed as Groucho in the vaudeville days; simply applying his signature glasses, along with a greasepaint mustache and eyebrows, would make brother look like brother. Anyway, Pinky breaks a large mirror, and when Firefly comes to investigate, he finds a curious reflection. The two engage in a brilliant pantomime in the empty mirror frame, incredibly timed and shot without sound or music—sound would be extraneous to this purely visual gag. Firefly tries to outwit his reflection to hilarious effect, and Chicolini spoils the ruse when he, too, enters dressed as Firefly. The Marxes supposedly reworked the mirror routine from a vaudeville act by the Schwartz Brothers from years earlier. That’s the trouble with vaudeville; no one was around to record these routines, leaving early cinematic comedies to seem pioneering. Even though the Marxes are often associated with (and perfected) the mirror routine, McCarey directed a similar scene in the Charlie Chase comedy Mum’s the Word (1926). Nevertheless, when Tom and Jerry, Abbott and Costello, and countless other performers repeat the gag, they do so by paying homage to the Marx Brothers, not the forgotten Schwartzes or Charlie Chase. The funniest of these offspring must be Hare Tonic, the Looney Tunes short from 1945 where Bugs Bunny uses the mirror routine to convince Elmer Fudd that he’s been turned into a wabbit, complete with wabbit ears and a wagging wabbit tail.

Individual gags aside, the political undercurrent of Duck Soup cannot help but correspond to history, which is perhaps why the film is viewed today as the Marx Brothers’ most substantive comedy and an essential war picture. Many film scholars have pointed out that Duck Soup was released the same year that Adolf Hitler took power in Germany. Although the Marx Brothers were aware of the Anti-Semitism unfolding in Europe, like most Americans, they had no idea just how bad it would become. The warring countries of Freedonia and Sylvania were vague spoofs of the First World War, a distant reality from two decades earlier, not an accurate prediction of what would come. Still, there was something in the air—the same uncertainty and nationalistic movement that led to the First World War—and that made everyone on the set somewhat uneasy about making a war comedy in 1933. No one realized that Duck Soup would contain historical parallels abound or seem to have a foresight of the years to come. But like every great satire, Duck Soup speaks to eternal truths that reach beyond the surface. It was made with the same impulse as Armando Iannucci’s The Death of Stalin (2018), which identifies the dysfunction and absurdity of political systems, both in history and our contemporary world.

It is disturbing to think that Duck Soup contains just as many moments of recognition as it does nonsensical and tangential humor. The film raises so many questions about whether it is lampooning various dictators or political situations because history has a way of repeating itself. When Firefly kills his own men and then tries to cover it up, he does so two years before Humphrey Cobb wrote his book Paths of Glory, a real-life account of a French general who did the same thing during the First World War. When Firefly sings, “The last man nearly ruined this place/He didn’t know what to do with it/If you think this country’s bad off now/Just wait ‘til I get through with it,” try not to think of someone like Hitler or Donald Trump. Mussolini even banned Duck Soup in Italy after a twinge of recognition. To be sure, the film, either through intentional or coincidental circumstance, underlines a historical pattern of insane people taking over bankrupt nations. “It kidded dictators,” said McCarey. And who better to spoof a megalomaniacal leader than Groucho, who was often placed in charge where he did not belong? He ran a hotel in The Cocoanuts and a college in Horse Feathers; putting him in charge of a country was a natural progression. Only Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1941) would make a more blatant attack on autocratic leaders.

No wonder Duck Soup, and by extension each of the Marx Brothers’ films, found new life in the counterculture movement of the 1960s. At every turn, the Marxes destabilize social norms, question authority, and take down the establishment with their antics. College campuses rallying against America’s presence in Vietnam, the presidency of Richard Nixon, institutional racism, and the patriarchy had found a hero in Groucho and his brothers. In every Marx Brothers comedy, they upset the order of things and mock people who take themselves too seriously. Though usually, authority figures remain oblivious to what the Marx Brothers are up to—that secret is shared exclusively with the audience. Leonard Maltin said their body of work “deflates pomposity,” lending itself to anti-authoritarians who enjoy seeing those in charge disrupted and rendered powerless. The effect was never more clearly stated than in their song “I’m Against It” in Horse Feathers, where Groucho sings, “Your proposition may be good/But let’s have one thing understood/Whatever it is, I’m against it.” Even within the world of comedy, their presence is chaotic and counter to the usual modes. This is the stuff of Andy Kaufman and Monty Python, those performers who break the mold. As Roger Ebert observed, “you can see who the Marx Brothers inspired, but not who they were inspired by,” and that history has made them true originals.

Although it would be easy to quote every line of Duck Soup and dwell on the individual moments of unconventional humor, one after another, which ring in our memory and preserve its place in the comedy pantheon, the film’s history carves out its place of distinction. Duck Soup remains an oddity and transitional film in the Marx Brothers’ career. It was the first film they would make after both of their parents were gone, and the last film they would make as a foursome. It eschewed many of the downfalls that would typify their pictures at Paramount and MGM, such as an overreliance on musical numbers or romantic subplots. It concentrates the Marx Brothers’ comedy to its essence, whereas everything that came before and after feels somehow diluted. It does not sentimentalize or pretend to pull at the viewer’s heartstrings; it allows the brothers to do what they do best—incite chaos. Another famous Jewish comedian from New York once said that, of all comedies, “Duck Soup is the only one that really doesn’t have a dead spot.” It’s also the rare work from the Marxes’ career that seems to reverberate through history, if only because it emphasizes a pattern of behavior among totalitarians through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In another way, Duck Soup might be the only Marx Brothers film that feels completely in tune with their brand of humor, which, then and now, is downright radical.

Bibliography:

Adamson, Joe. Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Sometimes Zeppo: A Celebration of the Marx Brothers. Simon and Schuster, 1973.

Bader, Robert S. Four of the Three Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage. Northwestern University Press, 2016.

Blount, Jr., Roy. Hail, Hail, Euphoria: Presenting the Marx Brothers in Duck Soup, the Greatest War Movie Ever Made. HarperCollins, 2010.

Haas, Scott. “The Marx Brothers, Jews, & My Four-Year-Old Daughter.” Cinéaste, vol. 19, no. 2/3, 1992, pp. 48–49. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41687199. Accessed 1 June 2020.

Liebenson, Donald. “Duck Soup at 85: Make Freedonia Great Again.” RogerEbert.com. 3 Jan 2020. https://www.rogerebert.com/features/duck-soup-at-85-make-freedonia-great-again. Accessed 29 May 2020.

Louvish, Simon. Monkey Business: The Lives and Legends of the Marx Brothers. Thomas Dunne Books, 2000.

Marx, Groucho. Groucho and Me. Random House, 1959.

Marx, Harpo, and Rowland Barber. Harpo Speaks! Limelight Editions, 2004 (org. 1961).

Silver, Charles. “Leo McCarey from Marx to McCarthy.” Film Comment, vol. 9, no. 5, 1973, pp. 8–11. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43451210. Accessed 1 June 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review