The Definitives

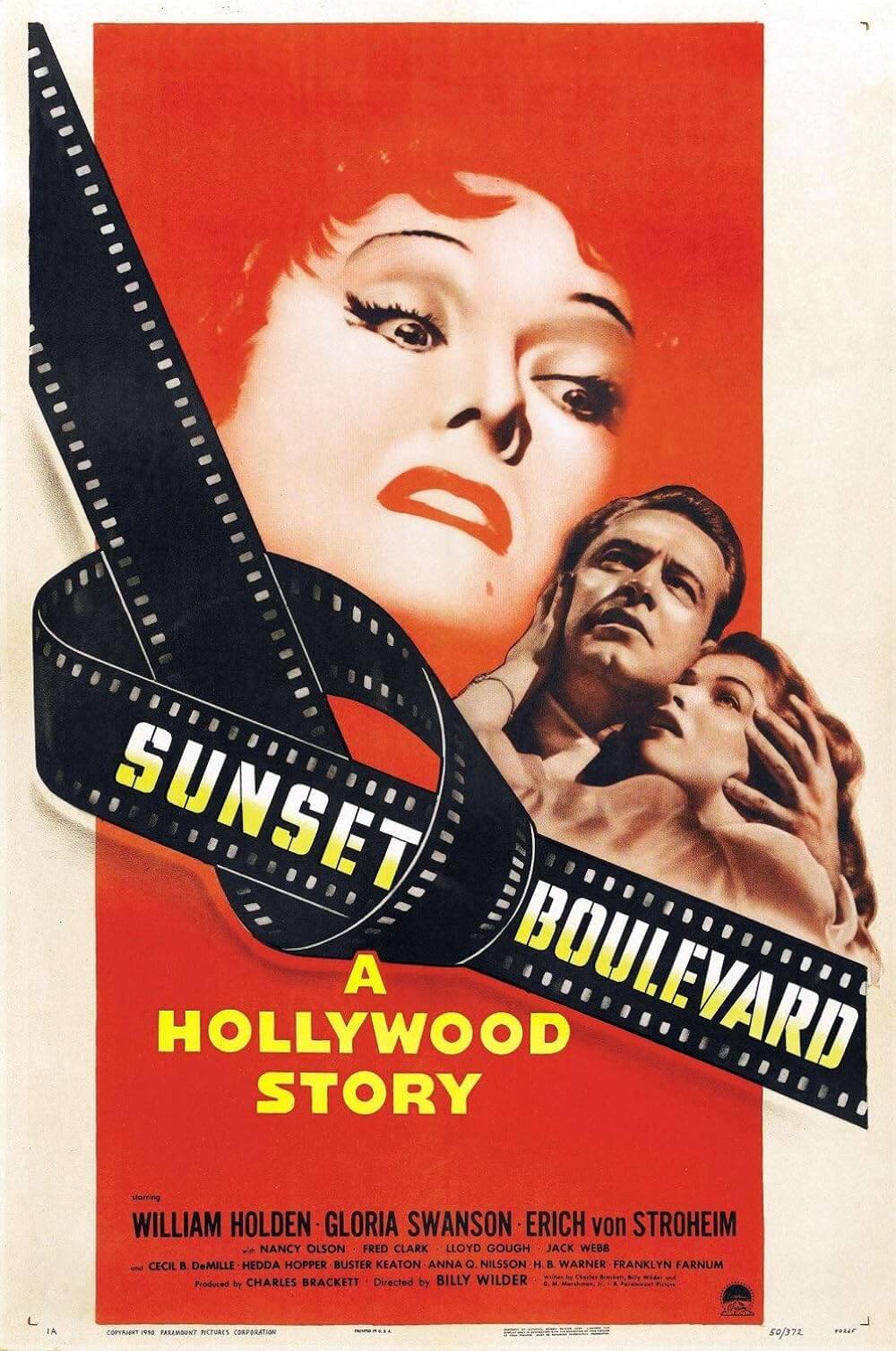

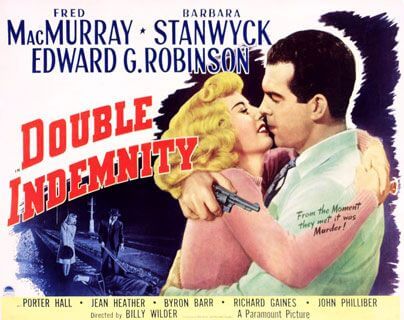

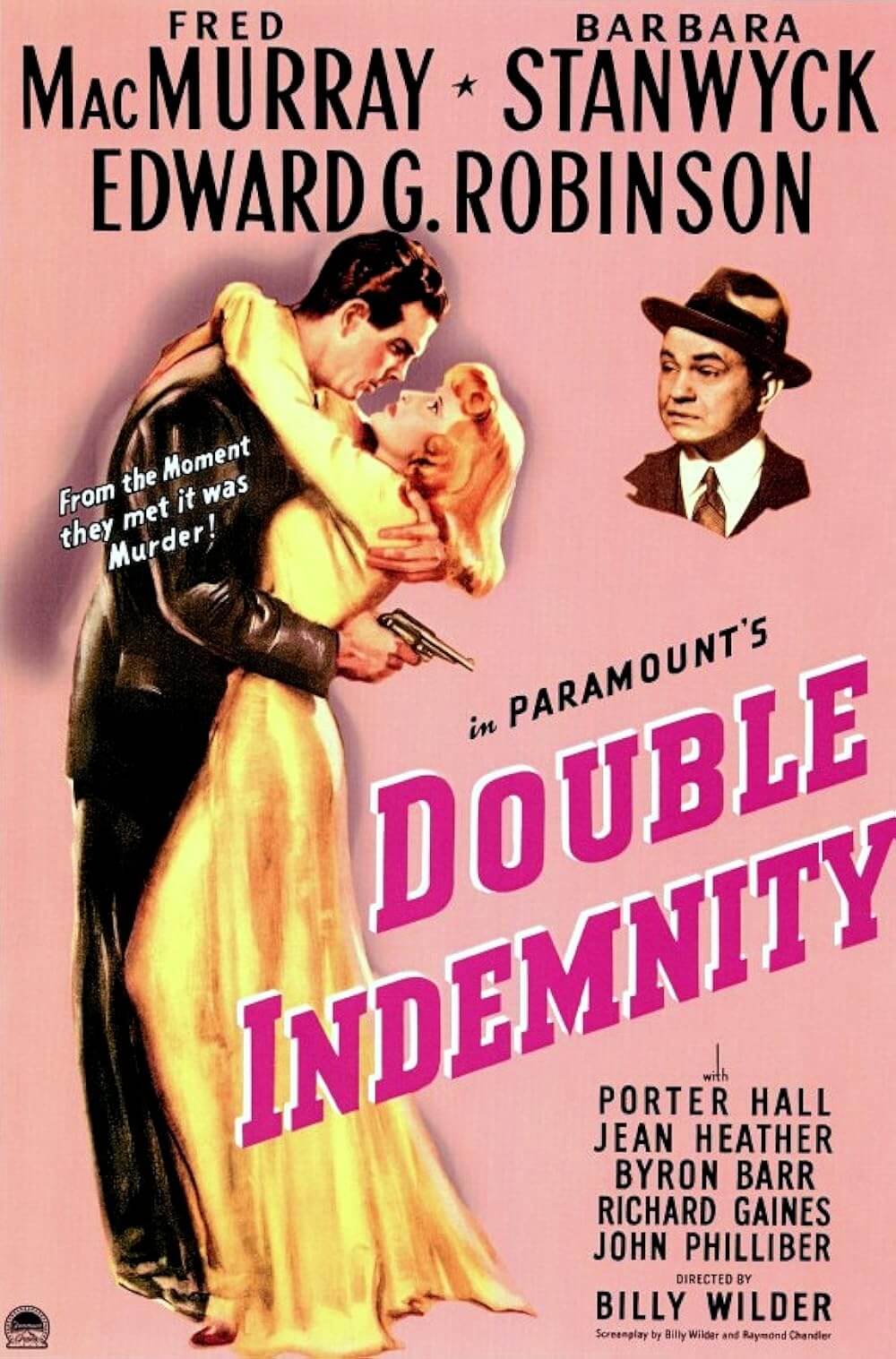

Double Indemnity (1944)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Insurance salesman Walter Neff’s mind isn’t so much on renewing his client’s automobile policy as landing the man’s blonde bombshell wife, Phyllis. She first appears to Walter at the top of the staircase, wrapped in nothing more than a towel. When she finally joins Walter downstairs, they exchange a few keen flirtations in the California sunlight, which streams through the Venetian blinds, illuminating the room’s dust and splashing bold horizontal shadows onto the walls and furniture. After another meeting like this one, their casual flirtation shifts to planning a murder. A tale of lust and greed delivered with a careful balance of elegance and vulgarity, Double Indemnity is based on the 1935 novel by James M. Cain. Billy Wilder directs and, alongside his co-writer Raymond Chandler, he adapted the book into something far more vibrant and smooth than the source material. Murder, sex, and greed saturate the screen, which the 1944 film steeps in film noir aesthetics, brazen wickedness, and cunning dialogue. Sharp shadows represent the chiaroscuro moral leaps made by the protagonists, neither of whom would have made such leaps alone without the other to encourage them. Miklos Rosa’s winding score ties the viewer up in the suspense. And Walter’s enduring voiceover carries us through the detailed proceedings in hard-boiled descriptions. Double Indemnity remains a cynical and shrewd motion picture, full of wit and acid; it’s also unexpectedly humorous and quirky. But then, this could be said of many Billy Wilder films.

Double Indemnity also stands among the most singular examples of film noir; though, like many of its kind, it predates the term that defines it. The first noted use of the term “film noir” appeared in the French film journal L’Écran français in 1946, used by Nino Frank. However, Frank derived the term from roman noir, a brand of tough French fiction that emulated American crime authors from the 1930s and 1940s (such as Cain, Raymond Chandler, W. R. Burnett, Dashiell Hammett, and others—authors Cain referred to as “the poets of the tabloid murder”). Many of the earliest cinematic examples of film noir draw from those very same authors. Film noirs, best recognized for a visual style rooted in shadows, take a stylistic cue from German Expressionism, a movement Wilder was familiar with from his years in the Weimar-era film industry in Germany. Although Wilder was among the earliest to flee Germany after Hitler’s rise to power, the high-contrast lighting of the German style continued to influence his work after he arrived in America in 1933. But film noirs are about more than just visual aesthetics; they embrace the theme of light and dark in their storylines, drawing inspiration from the lows people reached during and after World War II. Their stories regularly follow detectives (both private and official) or simply confident men who lose themselves in a dark underworld. Noir heroes, sometimes lured into the underworld by a femme fatale, finally meet their fateful demise, whether it’s physical or existential.

Double Indemnity’s plot details are less important than the way Wilder frames the story—in flashback, by Pacific All Risk Insurance Company salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), who recounts his tale by way of confession into a Dictaphone. When he meets Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), his client’s wife, she seduces Walter into a deadly scheme: Walter must sell her husband (Tom Powers) an accident insurance policy with a $50,000 payout. Then, the two must murder her husband and make it look accidental for the company to pay. They plan the murder around Mr. Dietrichson’s college reunion trip. Walter insists that Phyllis convince her husband to travel by train; a double indemnity clause pays $100,000 if an accident involves a locomotive. As Phyllis drives her husband to the station, Walter hides in the back seat until he receives an all-clear signal, then he strangles Mr. Dietrichson. Walter impersonates him on the train to create witnesses, and after they establish people have seen “Mr. Dietrichson,” Walter jumps off to help Phyllis arrange their victim’s corpse on the tracks, making it look as though her husband fell off. All goes smoothly until Phyllis tries to start the car afterward; the engine struggles to turn over, cranking for what seems an eternity. Wilder forced Stanwyck to hold the engine past the point that felt reasonable to her. It’s among many of the film’s breathless sequences. Another requires Phyllis to hide behind the door at Walter’s apartment because he’s received a surprise visit from Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), his friend and Pacific All Risk’s wily claims investigator.

Double Indemnity’s plot details are less important than the way Wilder frames the story—in flashback, by Pacific All Risk Insurance Company salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), who recounts his tale by way of confession into a Dictaphone. When he meets Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), his client’s wife, she seduces Walter into a deadly scheme: Walter must sell her husband (Tom Powers) an accident insurance policy with a $50,000 payout. Then, the two must murder her husband and make it look accidental for the company to pay. They plan the murder around Mr. Dietrichson’s college reunion trip. Walter insists that Phyllis convince her husband to travel by train; a double indemnity clause pays $100,000 if an accident involves a locomotive. As Phyllis drives her husband to the station, Walter hides in the back seat until he receives an all-clear signal, then he strangles Mr. Dietrichson. Walter impersonates him on the train to create witnesses, and after they establish people have seen “Mr. Dietrichson,” Walter jumps off to help Phyllis arrange their victim’s corpse on the tracks, making it look as though her husband fell off. All goes smoothly until Phyllis tries to start the car afterward; the engine struggles to turn over, cranking for what seems an eternity. Wilder forced Stanwyck to hold the engine past the point that felt reasonable to her. It’s among many of the film’s breathless sequences. Another requires Phyllis to hide behind the door at Walter’s apartment because he’s received a surprise visit from Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), his friend and Pacific All Risk’s wily claims investigator.

Whatever lustful passions that may have existed between Walter and Phyllis quickly disappear after the murder. Walter is rapt with dread. “I couldn’t hear my own footsteps,” he narrates in one scene. “It was the walk of a dead man.” He begins to rethink everything, especially Phyllis. He’s since learned from Phyllis’ step-daughter Lola (Jean Heather) that Phyllis was once the nurse of the previous Mrs. Dietrichson, Lola’s mother, who died under mysterious circumstances. In all likelihood, Phyllis killed once before to get what she wants, and now she’s convinced Walter to help her do it again. “We’re both rotten,” she says, faking guilt so as not to appear heartless. Walter replies, “Only you’re a little more rotten.” Walter continues to learn more about Phyllis as the heat increases. It turns out she’s been seeing Lola’s boyfriend on the side, a young man named Nino (Byron Barr). Keyes, who investigates the case for Pacific All Risk, believes Phyllis and Nino planned the entire murder. Walter knows that Keyes suspecting Phyllis means he’s getting one step too close. He resolves to rid himself of Phyllis, but she shoots him first when they meet, wounding him. “I never loved you, Walter,” she says. “Not you or anybody else. I’m rotten to the heart… I used you, just as you said. That’s all you ever meant to me… Until a minute ago, when I couldn’t fire that second shot.” Walter doesn’t buy it. He shoots and kills her. Wounded and struggling, he makes his way back to the Pacific All Risk office and records his story for Keyes, who finds him and calls an ambulance.

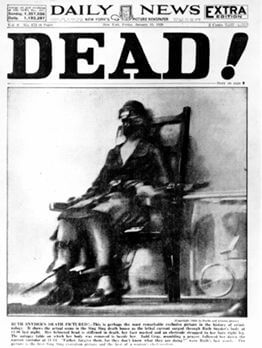

The basic plot of Double Indemnity takes considerable liberties with its source. Cain based his book on a notorious New York murder from the 1920s, in which Queens housewife Ruth Snyder convinced her lover Judd Gray to kill her husband. Ruth, who had tried to kill her husband Albert several times before (a detail that apparently escaped him), convinced Albert to buy a life insurance policy with a double indemnity clause, granting an increased payout in some instances, including murder. Gray, a corset salesman with a wife and child, began sleeping with Snyder after selling her a corset. When they eventually joined forces to kill Albert, they hit him on the head with an iron, chloroformed him, and strangled him to death with some wire. They staged the scene to look like a burglary had occurred and relied on a friend from Syracuse to provide an alibi for Gray—a friend who later confessed his role in the murder when questioned by police, leading to Snyder and Gray’s capture. They were quickly detained by authorities, jailed in Sing Sing, and later sentenced to the electric chair. The arrest, court case, and following execution ripped through the headlines and drew massive public interest. The Daily News even managed to snap and publish a famous photo of Ruth at the very moment her body was jolted with electricity (“DEAD!” read the headline). Much of the press coverage at the time remarked how stupid a crime it was, but more than that, it was an ugly crime. The press considered Snyder and Gray pathetic for committing seedy actions in ways only lowlives could imagine. Cain was undoubtedly attracted to the subject matter because his 1934 novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice, also involved a woman who convinced another man to murder her husband.

The basic plot of Double Indemnity takes considerable liberties with its source. Cain based his book on a notorious New York murder from the 1920s, in which Queens housewife Ruth Snyder convinced her lover Judd Gray to kill her husband. Ruth, who had tried to kill her husband Albert several times before (a detail that apparently escaped him), convinced Albert to buy a life insurance policy with a double indemnity clause, granting an increased payout in some instances, including murder. Gray, a corset salesman with a wife and child, began sleeping with Snyder after selling her a corset. When they eventually joined forces to kill Albert, they hit him on the head with an iron, chloroformed him, and strangled him to death with some wire. They staged the scene to look like a burglary had occurred and relied on a friend from Syracuse to provide an alibi for Gray—a friend who later confessed his role in the murder when questioned by police, leading to Snyder and Gray’s capture. They were quickly detained by authorities, jailed in Sing Sing, and later sentenced to the electric chair. The arrest, court case, and following execution ripped through the headlines and drew massive public interest. The Daily News even managed to snap and publish a famous photo of Ruth at the very moment her body was jolted with electricity (“DEAD!” read the headline). Much of the press coverage at the time remarked how stupid a crime it was, but more than that, it was an ugly crime. The press considered Snyder and Gray pathetic for committing seedy actions in ways only lowlives could imagine. Cain was undoubtedly attracted to the subject matter because his 1934 novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice, also involved a woman who convinced another man to murder her husband.

Fortunately, Cain’s novel took a sharper approach to murder than the Snyder and Gray case. The author smartens up the adulterers, houses them in a classier, Californian setting, and simplifies the proceedings by making the insurance salesman one of the murderers. Their crime is far more calculated than Snyder and Gray’s, while their motivations of lust and greed are not so pure. And rather than allow them to be captured, Cain’s story ends with the murderers committing suicide. Despite the irresistible allure of Cain’s novel, Wilder’s longtime writing partner Charles Brackett refused to work on the picture, calling the story “disgusting.” Brackett had been an art critic for The New Yorker and remained somewhat elitist; he believed Cain’s material to be tawdry, immoral filth. He wasn’t the only one. When the story was first published in Liberty magazine, Cain’s agent sent it to Hollywood. Several studios were interested in adapting the novel. Still, the Hays Office shot down any hope of its adaptation, calling it a “blueprint for murder” and said it could be adapted “under no circumstances.” Not until Cain’s novel was published in book form did Wilder, at his home base of Paramount, become aware of it. He instantly loved the story and knew he could cleverly adapt it, sneaking its more controversial elements past the censors. Since Brackett refused to be involved, Wilder, who always worked better with a writing partner, sought Cain to co-write, but the author had been contracted by Fox for another assignment.

Wilder pursued Raymond Chandler instead. The mystery author of The Big Sleep (1939) and The Long Goodbye (1953), Chandler had never penned a screenplay and had little experience in Hollywood dealings. In their initial meeting, Chandler offered to write the script alone in about a week for one thousand dollars. Wilder agreed. Chandler returned with an unfinished product a week later, filled with director’s notes like “fade in” and “cut to black.” Moreover, Chandler had just taken large sections of Cain’s dialogue and transferred it to script formatting. “This is shit,” Wilder told him, and then he explained that he needed a partner to work out some of the clumsier details of Cain’s story. He explained that he and Chandler would write together, and the process would take as many as twelve weeks, and what’s more, the studio would pay Chandler two-thousand-a-week. Shocked at what they were willing to pay him, Chandler agreed. But the two writers did not get along well. Chandler, a former alcoholic, married to a woman twenty years older than him, smoked all day, refused to open windows, and had no sex life. Wilder felt he was a “disgruntled man” and was “a hard man to get a smile out of.” Wilder was just the opposite: A young filmmaker and all that Chandler despised about Hollywood. Wilder drank heavily and took breaks to entertain a string of young women, either on the phone or in the bedroom. Granted, Wilder and Brackett fought too, but theirs were collaborative spats that ended in progress—all part of a well-established routine.

Wilder pursued Raymond Chandler instead. The mystery author of The Big Sleep (1939) and The Long Goodbye (1953), Chandler had never penned a screenplay and had little experience in Hollywood dealings. In their initial meeting, Chandler offered to write the script alone in about a week for one thousand dollars. Wilder agreed. Chandler returned with an unfinished product a week later, filled with director’s notes like “fade in” and “cut to black.” Moreover, Chandler had just taken large sections of Cain’s dialogue and transferred it to script formatting. “This is shit,” Wilder told him, and then he explained that he needed a partner to work out some of the clumsier details of Cain’s story. He explained that he and Chandler would write together, and the process would take as many as twelve weeks, and what’s more, the studio would pay Chandler two-thousand-a-week. Shocked at what they were willing to pay him, Chandler agreed. But the two writers did not get along well. Chandler, a former alcoholic, married to a woman twenty years older than him, smoked all day, refused to open windows, and had no sex life. Wilder felt he was a “disgruntled man” and was “a hard man to get a smile out of.” Wilder was just the opposite: A young filmmaker and all that Chandler despised about Hollywood. Wilder drank heavily and took breaks to entertain a string of young women, either on the phone or in the bedroom. Granted, Wilder and Brackett fought too, but theirs were collaborative spats that ended in progress—all part of a well-established routine.

Wilder and Chandler’s changes involved plotting and simplifying Walter and Phyllis’ motivations to the primal drives of lust and greed, both notions often associated with Hollywood itself. They made several other changes to the dialogue. Cain wrote in a narrow style the eye could make sense of, but the ear could not. They brought in actors to speak Cain’s dialogue, and the experiment proved what they suspected: they would have to rewrite it. Cain himself, who sat in on these actor dialogue tests, even admitted his dialogue was not consistent with a motion picture. As Time‘s Richard Schickel pointed out in his essay on the film, the writers “sharpened and pointed” every aspect of Cain’s material; even the characters’ names became harder: Huff became Neff, Nirdlinger became Dietrichson. The screenwriters also pushed the sexual tension between Walter and Phyllis. In the book, when Walter first arrives at the Dietrichson home, he finds Phyllis in her pajamas; in the film, he sees her at the top of the stairs in nothing but a towel. “I’ve been sunbathing,” she says. “Hope there weren’t any pigeons around,” he responds. Later, their exchanges writhe with sexuality, teasing, and power plays. The quit-witted flirtations of the two offset the otherwise bleak storyline.

“Mr. Neff,” says Phyllis, “why don’t you drop by tomorrow evening about eight-thirty. He’ll be in then.”

“Who?”

“My husband. You were anxious to talk to him, weren’t you?”

“Yeah, I was. But I’m sort of getting over the idea, if you know what I mean.”

“There’s a speed limit in this state, Mr. Neff. 45 miles-an-hour.”

“How fast was I going, officer?”

“I’d say around ninety.”

“Suppose you get down off your motorcycle and give me a ticket.”

“Suppose I let you off with a warning this time.”

“Suppose it doesn’t take.”

“Suppose I have to whack you over the knuckles.”

“Suppose I bust out crying and put my head on your shoulder.”

“Suppose you try putting it on my husband’s shoulder.”

“That tears it.”

Meanwhile, Wilder and Chandler faced Hays representative Joseph Breen’s reservations about the book’s depiction of an “adulterous sex relationship” and characters who “die at their own hands” to rob authorities of exacting justice. Breen wrote, “The general low tone and sordid flavor makes it, in our judgment, thoroughly unacceptable for screen presentation.” However, Wilder was well aware that he and Chandler needed to change the material to Breen’s liking. Cain’s writing was blunt and didn’t dance around the cold, harsh reality of Walter and Phyllis’ relationship. The screenwriters toned down Phyllis’ barefaced psychopathy and added an artful, daresay, playful tone to the story and dialogue. Instead of a slap-in-the-face yarn about two killers, the film consisted of two love stories: the doomed one between Walter and Phyllis, and the one of moral responsibility and admiration between Walter and Keyes. Wilder and Chandler made another significant change to Cain’s text: the ending’s bleak double suicide. Instead, Walter kills Phyllis and nearly dies in the process, only to face Keyes in the final scene. Originally, Wilder and Chandler even penned a coda that finds Walter executed in the gas chamber.

Meanwhile, Wilder and Chandler faced Hays representative Joseph Breen’s reservations about the book’s depiction of an “adulterous sex relationship” and characters who “die at their own hands” to rob authorities of exacting justice. Breen wrote, “The general low tone and sordid flavor makes it, in our judgment, thoroughly unacceptable for screen presentation.” However, Wilder was well aware that he and Chandler needed to change the material to Breen’s liking. Cain’s writing was blunt and didn’t dance around the cold, harsh reality of Walter and Phyllis’ relationship. The screenwriters toned down Phyllis’ barefaced psychopathy and added an artful, daresay, playful tone to the story and dialogue. Instead of a slap-in-the-face yarn about two killers, the film consisted of two love stories: the doomed one between Walter and Phyllis, and the one of moral responsibility and admiration between Walter and Keyes. Wilder and Chandler made another significant change to Cain’s text: the ending’s bleak double suicide. Instead, Walter kills Phyllis and nearly dies in the process, only to face Keyes in the final scene. Originally, Wilder and Chandler even penned a coda that finds Walter executed in the gas chamber.

Though the collaboration was filled with mutual antipathy, Wilder and Chandler finished their script in September 1943. All the while, Wilder had been casting. MacMurray had starred in Paramount musicals and comedies like The Bride Comes Home (1936) and Star Spangled Rhythm (1942) before Wilder pestered him about appearing in Double Indemnity. Accepting the role of Neff would mean a complete career shift for the square-jawed, affable, and all-American actor. Paramount didn’t mind. MacMurray had been complaining about his contract for some time. Since the studio believed the film would tank at the box office given its subject matter, they felt allowing him to star would take down the actor’s bankability, thus resolving their MacMurray problem. Stanwyck expressed similar concerns that starring as a cold-blooded killer might tarnish her reputation. She had come a long way from Baby Face (1933), her pre-Code drama in which she plays a sexually abused woman who takes vengeance on the men in the bank where she works. Since then, she had starred in a series of lovable crowd-pleasers like The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, and Ball of Fire—all released in 1941. To convince her to unleash that dark side again, Wilder asked, “Are you a mouse or an actress?” The actress signed.

Edward G. Robinson as Keyes is arguably Wilder and Chandler’s most significant contribution to the screenplay. Cain’s version of the character didn’t have much depth or significance, but in Wilder and Chandler’s text, he becomes an idiosyncratic figure of strange little habits and obsessions. He’s also the emotional crux of the film. He’s a funny sort of man who stands about a foot shorter than MacMurray. He always needs a light for his cigars, and Walter always has a match ready with the flick of his thumbnail. Keyes also speaks of an imaginary little man inside him who becomes unsettled whenever something about a case doesn’t make sense. At times, he seems charmingly comical in his unsettled suspicions, but this is Wilder and Chandler’s clever way of creating suspense around Walter’s fear of being discovered. “A claims man is a doctor and a bloodhound and a cop and a judge and a jury and a father confessor,” Keyes proclaims, solidifying the notion of his absolute moral authority—or even a father figure for Walter. Keyes represents the moral side of Double Indemnity; he reminds us that what Walter and Phyllis are planning is wrong. And yet, there’s an unspoken bond between these two men, as Walter, an amoral salesman, looks up to Keyes. After all, Walter chooses to confess his crimes via Dictaphone to Keyes, not the general authorities. “You know why you couldn’t figure this one, Keyes? I’ll tell you,” says Walter. “Because the guy you were looking for was too close—right across the desk from you.” Keyes says, “Closer than that, Walter.” Neff responds, “I love you, too.” For all the film’s stylistic innovations and punchy dialogue, the unique relationship between Walter and Keyes turns this lowdown tale of murder and lust into a tragedy. Walter tries to meet the expectations he’s set for himself based on his admiration of Keyes. But this leads to the heartrending moment where Keyes lights Walter’s cigarette in his last moments.

Edward G. Robinson as Keyes is arguably Wilder and Chandler’s most significant contribution to the screenplay. Cain’s version of the character didn’t have much depth or significance, but in Wilder and Chandler’s text, he becomes an idiosyncratic figure of strange little habits and obsessions. He’s also the emotional crux of the film. He’s a funny sort of man who stands about a foot shorter than MacMurray. He always needs a light for his cigars, and Walter always has a match ready with the flick of his thumbnail. Keyes also speaks of an imaginary little man inside him who becomes unsettled whenever something about a case doesn’t make sense. At times, he seems charmingly comical in his unsettled suspicions, but this is Wilder and Chandler’s clever way of creating suspense around Walter’s fear of being discovered. “A claims man is a doctor and a bloodhound and a cop and a judge and a jury and a father confessor,” Keyes proclaims, solidifying the notion of his absolute moral authority—or even a father figure for Walter. Keyes represents the moral side of Double Indemnity; he reminds us that what Walter and Phyllis are planning is wrong. And yet, there’s an unspoken bond between these two men, as Walter, an amoral salesman, looks up to Keyes. After all, Walter chooses to confess his crimes via Dictaphone to Keyes, not the general authorities. “You know why you couldn’t figure this one, Keyes? I’ll tell you,” says Walter. “Because the guy you were looking for was too close—right across the desk from you.” Keyes says, “Closer than that, Walter.” Neff responds, “I love you, too.” For all the film’s stylistic innovations and punchy dialogue, the unique relationship between Walter and Keyes turns this lowdown tale of murder and lust into a tragedy. Walter tries to meet the expectations he’s set for himself based on his admiration of Keyes. But this leads to the heartrending moment where Keyes lights Walter’s cigarette in his last moments.

Filming began on September 27, and once again, Wilder teamed with cinematographer John Seitz, who shot the director’s second feature, Five Graves to Cairo (1943). But Seitz’s flexibility meant he could change his approach based on the director’s needs. Seitz captures deep, gloomy light peering through and bouncing off the subtly suggestive interiors by set designer Hal Pereira. To achieve that iconic way the light illuminates dust in the Dietrichson home, Seitz used finely ground aluminum filings to reflect the light enough for the camera to capture. Or look at the way Walter’s unglamorous apartment reflects his spare, unattached lifestyle; one can imagine him lying on his bed at night, dreaming up the perfect murder. Inside the grocery store where Walter and Phyllis meet to plan their crime, the entire set looks angular and rigid, as though the store has remained untouched since it opened. But then, Walter and Phyllis stand rigid, too, fearing they’ll be noticed together. The actors were also understandably severe behind-the-scenes, worried the film might bomb for its subject matter and ruin their careers. Their nervousness sharpened their performances. MacMurray was never better; Stanwyck was rarely better—her icy smile as Walter strangles Mr. Dietrichson is genuinely haunting. Shooting wrapped on November 24, finishing just under Paramount’s allotted budget of $980,000. By January, Wilder had completed Double Indemnity and knew he had a winner. He proclaimed his genius on the Paramount lot, suggesting he was the studio’s last real talent since Preston Sturges (The Lady Eve) left the studio.

Paramount’s promotional department arranged for Stanwyck’s appearance ads for Bates bedspreads, Deltah pearls, and Max Factor cosmetics—a strange choice, given that Stanwyck’s character is a heartless killer, responsible not only for coolly plotting her husband’s death but likely the death of her husband’s first wife as well. Equally strange was their cross-promotion with the Cigar Institute of America, which featured Walter, a killer, lighting Keyes’ cigar. Regardless of the studio’s curious marketing tactics, the film performed well enough for Paramount, although it was not one of 1944’s top box-office earners. The majority of reviews were positive, many of them citing Wilder’s superb direction and announcing his arrival as a prominent Hollywood filmmaker. Alfred Hitchcock even wired Wilder a note, “Since Double Indemnity the two most important words are Billy Wilder,” playing on one of the film’s marketing taglines: “Double Indemnity—The two most important words in the motion picture industry since Broken Blossoms.” Cain later said of the film, “It’s the only picture I ever saw made from my books that had things in it I wish I had thought of. Wilder’s ending was much better than my ending, and his device for letting the guy tell the story by taking out the office dictating machine—I would have done it if I had thought of it.” Wilder’s film was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won none of them. Many believe that Wilder’s Best Picture and Best Director win for the subsequent year’s The Lost Weekend were votes carried over for Double Indemnity. Perhaps this was because critics had difficulty categorizing it in 1944 since film noir had not yet been an established style.

Paramount’s promotional department arranged for Stanwyck’s appearance ads for Bates bedspreads, Deltah pearls, and Max Factor cosmetics—a strange choice, given that Stanwyck’s character is a heartless killer, responsible not only for coolly plotting her husband’s death but likely the death of her husband’s first wife as well. Equally strange was their cross-promotion with the Cigar Institute of America, which featured Walter, a killer, lighting Keyes’ cigar. Regardless of the studio’s curious marketing tactics, the film performed well enough for Paramount, although it was not one of 1944’s top box-office earners. The majority of reviews were positive, many of them citing Wilder’s superb direction and announcing his arrival as a prominent Hollywood filmmaker. Alfred Hitchcock even wired Wilder a note, “Since Double Indemnity the two most important words are Billy Wilder,” playing on one of the film’s marketing taglines: “Double Indemnity—The two most important words in the motion picture industry since Broken Blossoms.” Cain later said of the film, “It’s the only picture I ever saw made from my books that had things in it I wish I had thought of. Wilder’s ending was much better than my ending, and his device for letting the guy tell the story by taking out the office dictating machine—I would have done it if I had thought of it.” Wilder’s film was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won none of them. Many believe that Wilder’s Best Picture and Best Director win for the subsequent year’s The Lost Weekend were votes carried over for Double Indemnity. Perhaps this was because critics had difficulty categorizing it in 1944 since film noir had not yet been an established style.

As mentioned above, film noir was not a designation audiences were aware of in 1944. In fact, the term would not reach the U.S. until about a decade later. And despite many cinematic examples predating Double Indemnity, none tapped into the rawness of this film’s unique marriage of the thematic and visual. Wilder’s picture employs film noir themes both in Seitz’s bold use of shadows and in how Phyllis lures Walter out of the California sunshine and into the shadows of her murderous world. Many film noirs contain voiceover, but as Cain noted, none so effectively implement this genre device as Double Indemnity. Indeed, we understand what Cain meant by “the poets of the tabloid murder” as Walter speaks into the office dictation machine: “It was a hot afternoon,” he says. “I can still remember the smell of honeysuckle all along that street… How could I have known that murder can sometimes smell like honeysuckle?” Moreover, few film noirs are so overt in their standard theme, where attraction becomes infatuation, and that infatuation compels the hero to commit criminal acts. In the final moment between Phyllis and Walter, she shoots him and says she never loved him, and she comes close to shooting again. But then, at that moment, she seems to realize she did love him. “Just hold me,” she says. They embrace, though we see her eyes as she realizes Walter has put a gun to her side. “Goodbye, Baby,” he says, and shoots. The moment represents the sole release he ever achieves with Phyllis—that’s shown onscreen, anyway.

Double Indemnity represented an artistic benchmark for many Hollywood filmmakers interested in cynical, hard-boiled characters that seemed to reflect a war-torn culture. It shows us what happens when we embrace our lowest desires, when we no longer deny our covetous impulses, when we follow our most lustful drives, when the murderous thoughts we hold become a reality, and when we tell lies to cover up our crimes. It’s about people getting caught up in their desires and losing themselves; suddenly, there is no limit to the lengths they’ll go to get what they want. At the same time, Double Indemnity is about guilt and about looking back in hindsight on our choices. Without Wilder’s film, with its artistic prowess and merciless edge, it’s doubtful later film noir pictures like Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (1947), Jules Dassin’s Night and the City (1950), or Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) would have been considered by Hollywood. Yet, for all its influence and importance in film history, Double Indemnity remains a joy to watch. We can still savor the slick dialogue; Stanwyck’s sultry voice; the way MacMurray delivers every callous line with a smirk just under the skin; Robinson’s playful idiosyncrasies; Seitz’s beautiful photography; and Wilder, whose vision combined American crime and expressionistic style into an incomparable classic.

Double Indemnity represented an artistic benchmark for many Hollywood filmmakers interested in cynical, hard-boiled characters that seemed to reflect a war-torn culture. It shows us what happens when we embrace our lowest desires, when we no longer deny our covetous impulses, when we follow our most lustful drives, when the murderous thoughts we hold become a reality, and when we tell lies to cover up our crimes. It’s about people getting caught up in their desires and losing themselves; suddenly, there is no limit to the lengths they’ll go to get what they want. At the same time, Double Indemnity is about guilt and about looking back in hindsight on our choices. Without Wilder’s film, with its artistic prowess and merciless edge, it’s doubtful later film noir pictures like Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (1947), Jules Dassin’s Night and the City (1950), or Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) would have been considered by Hollywood. Yet, for all its influence and importance in film history, Double Indemnity remains a joy to watch. We can still savor the slick dialogue; Stanwyck’s sultry voice; the way MacMurray delivers every callous line with a smirk just under the skin; Robinson’s playful idiosyncrasies; Seitz’s beautiful photography; and Wilder, whose vision combined American crime and expressionistic style into an incomparable classic.

Bibliography:

Hopp, Glen. Billy Wilder: The Complete Films, The Cinema of Wit. Taschen, 2003.

Horton, Robert (editor). Billy Wilder: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2001.

McNally, Karen (editor). Billy Wilder, Movie-Maker: Critical Essays on the Films. McFarland, 2010.

Phillips, Gene D. Some Like It Wilder: The Life and Controversial Films of Billy Wilder. University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

Schickel, Richard. Double Indemnity. (BFI Film Classics). British Film Institute, 1992.

Sikov, Ed. On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder. Hyperion, 1998.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review