The Definitives

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

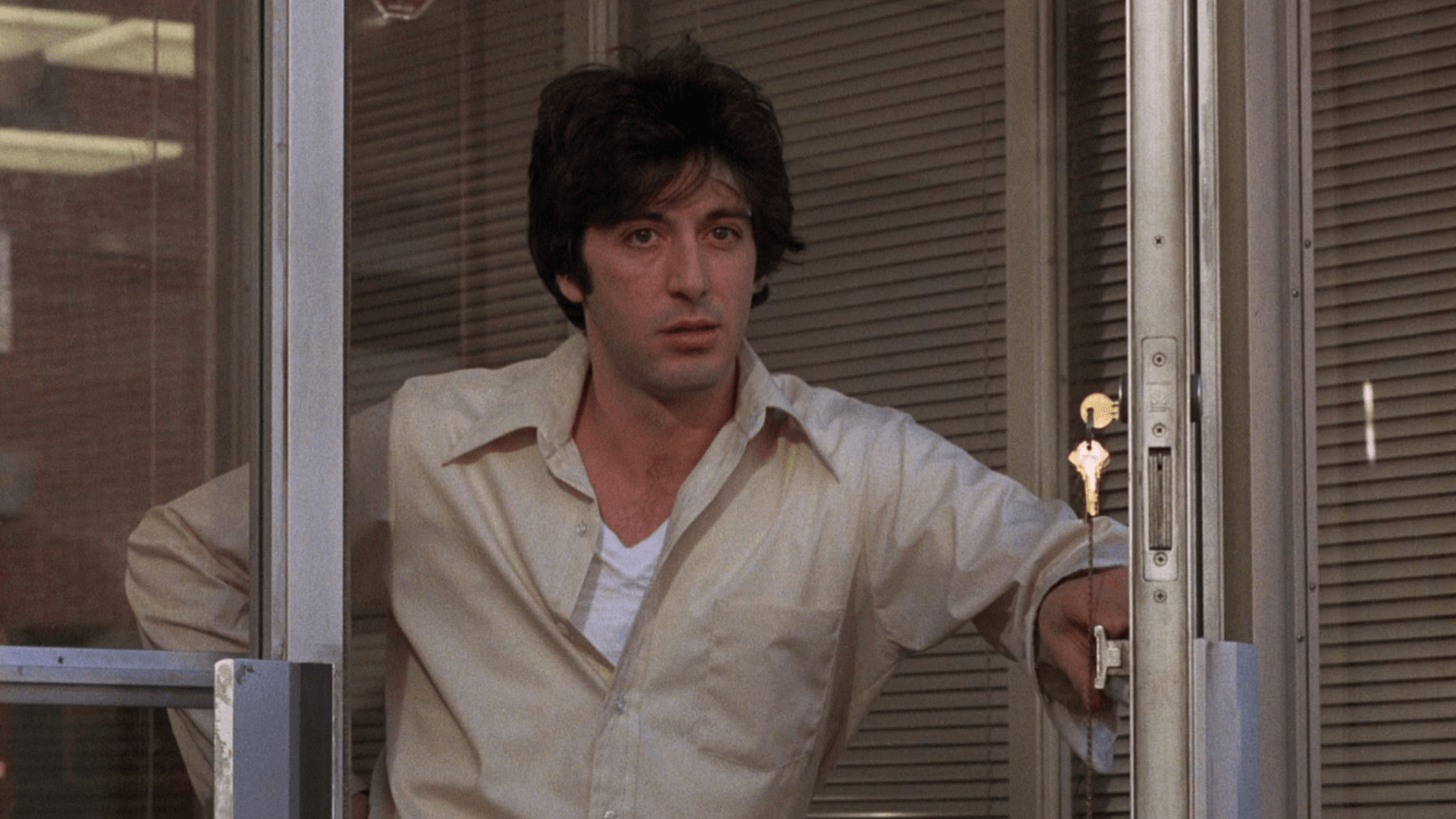

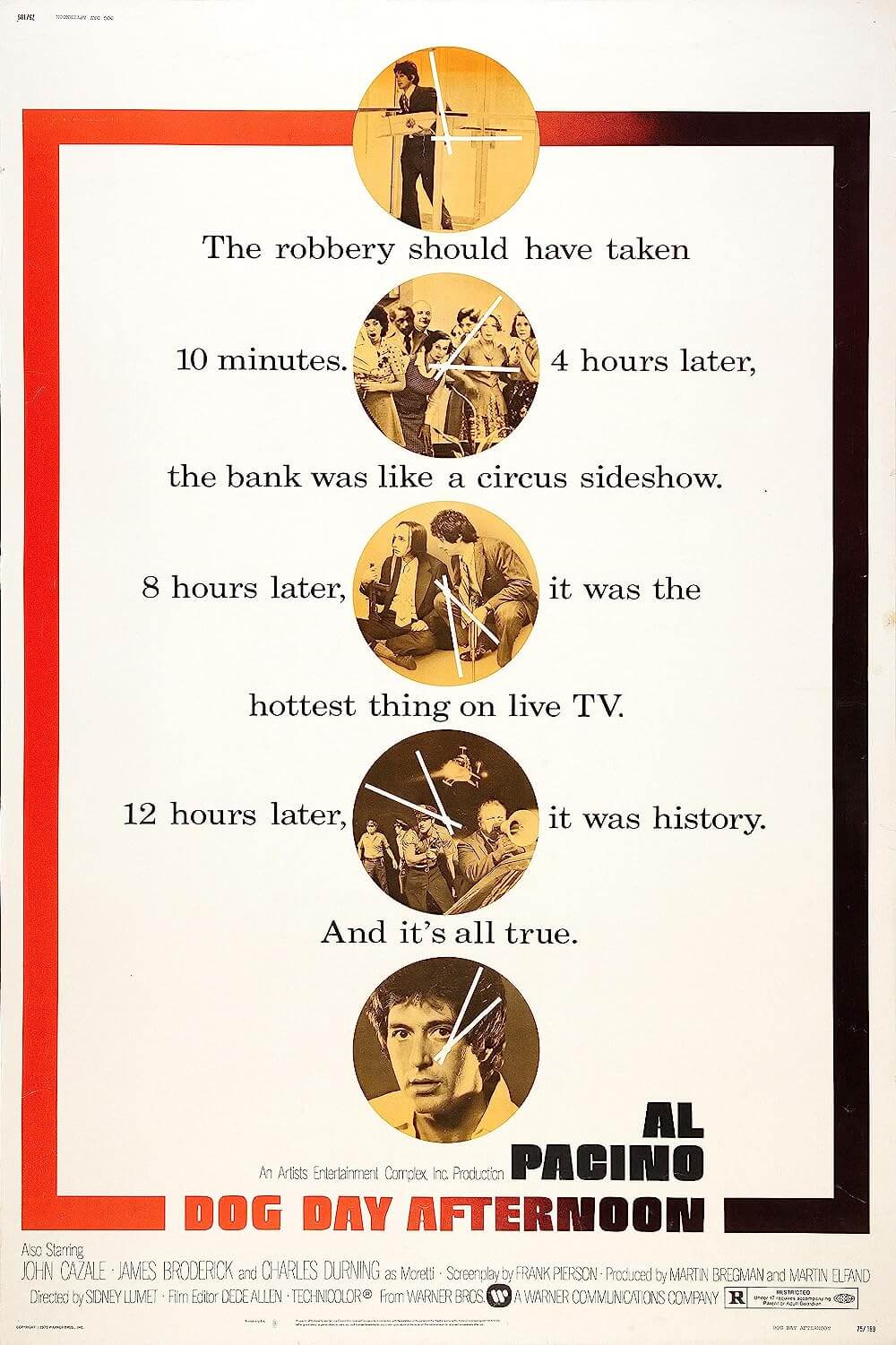

In Dog Day Afternoon, Sidney Lumet sought what he called “naturalism.” He directs the real-life story of a disastrous bank robbery, committed by two disenfranchised outcasts, with a constructed authenticity. Of course, the usual stock characters make appearances: two holdup men, a few hostages, a small army of cops, a police negotiator, and a crowd of onlookers. But among the countless films adhering to this formulaic scenario, Lumet’s treatment renders the chaotic ordeal with psychological depth, stylistic realism, and a tone that might be comic if not for the tragic conclusion. Working from an Oscar-winning screenplay that mostly adheres to the facts, Lumet’s desire for verisimilitude led him to adopt a documentary-like aesthetic and work with his performers to consider the inner lives of their characters. Together, these tactics would create veracity that lends the story genuine humanity, which proved all the more groundbreaking because its central character, played by Al Pacino, marked the first openly bisexual character to appear in a Hollywood film. What is more, the character appears not as a degrading Hollywood stereotype but as an everyday person with wants and desires. In 1975, such a conceit was not only unconventional but unprecedented. Only Lumet, with his application of formal techniques and close work with empathetic actors, could have turned this potentially sensationalistic or exploitative story into a melodrama of relatable characters. In doing so, he naturalizes an otherwise marginalized queer character for the first time in Hollywood history.

The opening titles read: “What you are about to see is true—It happened in Brooklyn, New York, on August 22, 1972.” The real story involved Vietnam veteran John “Sonny” Wojtowicz and his accomplice Salvatore “Sal” Naturile, who entered a Brooklyn branch of the Chase Manhattan Bank intending to rob the place. Sonny, a former bank teller, had inside information that this particular branch would have upwards of $200,000 in their vault that day. However, when he and Sal arrived, an armored pickup had already moved the hefty sum and gone, leaving the vault with only $29,000. What unfolded was a 15-hour holdup with eight hostages kept at gunpoint. Over one hundred police officers gathered at the scene. A crowd of thousands also formed to watch the spectacle unfold. Inside, Sonny talked to reporters over the phone and fuelled the media attention. The robbers made demands and ordered pizzas delivered by the FBI. The night-long ordeal ended early the next morning when federal agents escorted the two men, the bank manager, and the remaining bank employees to the Kennedy Airport for a plane getaway. On an isolated runway, an FBI agent shot Sal dead. Sonny immediately surrendered. Eventually, media reports revealed that Sonny hoped the robbery would provide enough money to finance a male-to-female sex reassignment surgery for his partner, whom he had married the year before.

The situation might have been less sensational if not for Sonny’s status as a bisexual man, then considered a sexual nonconformity and usually kept outside public view. Although the gay rights movement in the US had quietly gained traction for years, the police raid of the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich Village, in June 1969, prompted a riot involving over 400 protesters. Stonewall marked a defiant pronouncement of gay rights and would be commemorated yearly in June with Gay Pride celebrations. Even so, LGBTQ+ persons were still denied rights and treated with an otherness, contributing to the media circus around Sonny and Sal’s bank robbery that dominated television and radio broadcasts. It certainly caught the attention of producers Martin Bregman and Martin Elfand, who planned to develop P. F. Kluge and Thomas Moore’s Life magazine article, “The Boys in the Bank” (the film’s original title) into a juicy exploitation movie. But rather than turn the story into a so-called freak show, Lumet sought to humanize Sonny and Sal, therein normalizing queer identities. In his 1995 book Making Movies, Lumet described the theme of Dog Day Afternoon: “Freaks are not the freaks we think they are. We are much more connected to the outrageous behavior than we know or admit.” His view of the picture represented a shift from the exploitative intentions of B-movies to elevating the story to high drama, making it universally human.

Lumet came from Polish-Jewish emigrants who lived in Manhattan’s Lower East Side neighborhood and performed in the Yiddish theater. There, he got his start as an actor at age 5. As a young man who appeared in Broadway productions and evolved into an acting instructor, he worked alongside Elia Kazan, Lee Strasberg, and Cheryl Crawford to develop what would become the Actors Studio. After serving in World War II, he returned and recognized he would never have a career as a performer; his place was directing—first stage plays, then eventually in the experimental “golden age” of live television. Working for CBS in their New York studio during television’s infancy, he shot hundreds of episodes of shows such as the adventure anthology Danger (1950–55) and the historical reenactment program You Are There (1953–57), often experimenting with the medium and introducing new technical tricks that crackled with visual bravado. His aesthetic often hewed toward realism, albeit with subtle visual stylizations that sometimes go unnoticed by critics. Lumet also excelled as a director because of his knack for schematic thinking, a requirement of shooting sometimes-live productions for TV. His ability to map out an entire shoot and execute it according to that plan made his transition into cinema a natural one. Though, he remained a Hollywood outsider, mainly because he was committed to shooting in New York. Still, the studios liked Lumet because he delivered finished products on time and often on or under budget.

Lumet came from Polish-Jewish emigrants who lived in Manhattan’s Lower East Side neighborhood and performed in the Yiddish theater. There, he got his start as an actor at age 5. As a young man who appeared in Broadway productions and evolved into an acting instructor, he worked alongside Elia Kazan, Lee Strasberg, and Cheryl Crawford to develop what would become the Actors Studio. After serving in World War II, he returned and recognized he would never have a career as a performer; his place was directing—first stage plays, then eventually in the experimental “golden age” of live television. Working for CBS in their New York studio during television’s infancy, he shot hundreds of episodes of shows such as the adventure anthology Danger (1950–55) and the historical reenactment program You Are There (1953–57), often experimenting with the medium and introducing new technical tricks that crackled with visual bravado. His aesthetic often hewed toward realism, albeit with subtle visual stylizations that sometimes go unnoticed by critics. Lumet also excelled as a director because of his knack for schematic thinking, a requirement of shooting sometimes-live productions for TV. His ability to map out an entire shoot and execute it according to that plan made his transition into cinema a natural one. Though, he remained a Hollywood outsider, mainly because he was committed to shooting in New York. Still, the studios liked Lumet because he delivered finished products on time and often on or under budget.

Part of Lumet’s efficiency as a filmmaker stems from his frequent label as an “actor’s director.” His process and close work with performers, detailed in Making Movies, spans his 50-year career, ranging from his superb debut, 12 Angry Men (1957), to his excellent final film, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007). Lumet used the same preproduction process his entire career, starting with anywhere from two to four weeks of rehearsals with actors to find their characters, revise the script if necessary, block scenes, and generally create a road map of the film before cameras began to roll. These weeks allowed the actors to understand their characters and hone their performances. It also made the shoot a matter of capturing what had already been prepared and agreed upon in rehearsals. During this time, Lumet often directed his actors to work from the inside out. Although he collaborated with performers who used techniques including method acting, classical training from the British stage, and a self-taught approach, he encouraged them to find a character’s inner life and understand them as human beings. Such rigorous preplanning made Lumet famous for rarely shooting more than a few takes, allowing his productions to move fast and on schedule.

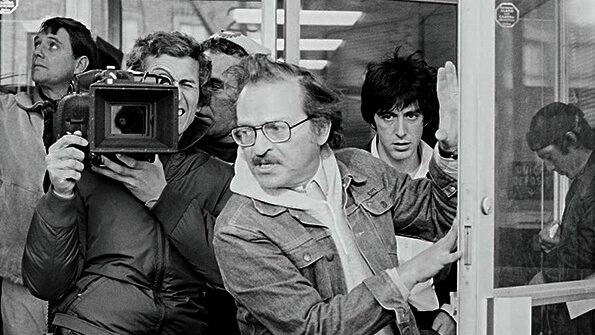

Lumet was also a believer in the philosophy that form should follow function, or that a film’s theme should inform its style. This is never more evident than in Dog Day Afternoon, where Lumet sought to underscore the reality of what took place on that hot day in 1972 with what he described as “close to documentary filmmaking as one can get in a scripted movie.” He wanted to “make sure that you never felt it was a movie, that you felt in essence you were watching a newsreel.” So Lumet and cinematographer Victor J. Kemper went out into the streets of New York, guerilla-style, and captured shots of everyday life in sweltering temperatures. They appear in the film’s first opening montage: a dog rummaging through garbage, people sitting around outside and talking, a public pool, a construction site, heavy traffic, a busy beach, homeless people, businessmen, and various other scenes. Then Sonny (Al Pacino), Sal (John Cazale), and Stevie (Gary Springer) appear in a car in front of a bank, looking no different than the everyday people of New York. They step out, one by one, and enter the bank near closing time. To further the natural look, Lumet insisted his cast use their personal clothes and do their own makeup for the production, removing any Hollywood gloss. Lumet and Kemper also used no artificial light sources, relying on the bank’s fluorescent bulbs and emergency lights for the interiors. At night, the light source came from the police spotlights and street lamps outside.

Almost immediately in the film, things go wrong. Dog Day Afternoon isn’t a slick heist film where the robbers have spent weeks pouring over bank blueprints and refining every detail of their score. Instead, Stevie tells Sonny that he’s “getting really bad vibes.” When Sonny pulls out his shotgun from a flower box, it gets caught in the ribbon, and he struggles with it for a moment. Details such as this suggest Lumet’s slice-of-life approach to the melodramatic material, introducing everyday slip-ups and comic foibles into a high-stakes scenario to heighten the naturalism. Just as Sonny’s “this is a robbery” routine begins, Stevie says he wants out. Sonny tells him not to take the getaway car, and Stevie whines about how he’ll get home. It’s a hilarious moment, and the audience feels Sonny’s tension. Now Sonny’s momentum has been thrown off, and the pressure visibly strains him. Worse, Sonny and Sal quickly learn the vault is nearly empty; its contents have been picked up already, leaving only $1,100 in the vault (dramatically less than the actual robbery). The situation has descended into a comedy of errors. And after they’ve collected their loot and there’s about a minute before Sonny and Sal can make their escape, Detective Moretti (Charles Durning) calls from across the street. He will stumble through negotiations. Outside, police officers gather, and so does a massive crowd of spectators and news crews. Snipers take their positions. Police and media helicopters circle overhead. Sonny threatens violence and makes demands. The police bring Sonny’s wife, Leon (Chris Sarandon), fresh from Bellvue Hospital after an attempted suicide, to talk. Before long, the FBI arrives and takes over, pretending to give Sonny and Sal their demands—a plane to anywhere. But the film ends just like the real-life story, with Sal dead and Sonny arrested.

Almost immediately in the film, things go wrong. Dog Day Afternoon isn’t a slick heist film where the robbers have spent weeks pouring over bank blueprints and refining every detail of their score. Instead, Stevie tells Sonny that he’s “getting really bad vibes.” When Sonny pulls out his shotgun from a flower box, it gets caught in the ribbon, and he struggles with it for a moment. Details such as this suggest Lumet’s slice-of-life approach to the melodramatic material, introducing everyday slip-ups and comic foibles into a high-stakes scenario to heighten the naturalism. Just as Sonny’s “this is a robbery” routine begins, Stevie says he wants out. Sonny tells him not to take the getaway car, and Stevie whines about how he’ll get home. It’s a hilarious moment, and the audience feels Sonny’s tension. Now Sonny’s momentum has been thrown off, and the pressure visibly strains him. Worse, Sonny and Sal quickly learn the vault is nearly empty; its contents have been picked up already, leaving only $1,100 in the vault (dramatically less than the actual robbery). The situation has descended into a comedy of errors. And after they’ve collected their loot and there’s about a minute before Sonny and Sal can make their escape, Detective Moretti (Charles Durning) calls from across the street. He will stumble through negotiations. Outside, police officers gather, and so does a massive crowd of spectators and news crews. Snipers take their positions. Police and media helicopters circle overhead. Sonny threatens violence and makes demands. The police bring Sonny’s wife, Leon (Chris Sarandon), fresh from Bellvue Hospital after an attempted suicide, to talk. Before long, the FBI arrives and takes over, pretending to give Sonny and Sal their demands—a plane to anywhere. But the film ends just like the real-life story, with Sal dead and Sonny arrested.

Lumet calibrated his entire production to give the audience a really there sense of space and time. Note that the screenplay contains no flashbacks; the story’s immediacy stems from the film’s immersion in the here and now. This applies to aspects of the technical production as well. Shooting inside an actual bank would have limited the camera’s movements, but building a bank set in a studio would have looked stagey. So instead, Lumet resolved to rent a warehouse and construct a bank set with removable walls, large enough to accommodate the camera for interiors and exteriors, rendering a convincing on-location set. But there are hints of subtle stylization as well. Lumet and the set decorator assemble a claustrophobic bank interior composed of flat surfaces in colors of gray and beige and sparsely decorated. As a result, the surfaces disappear into the backdrop—a tactic that heightens Sonny and Sal’s sense of feeling trapped in an unadorned and prison-like room. It also forces the viewer to focus on the actors in the intimate scenes inside the bank because the setting becomes recessive and flat. By contrast, the overstimulated exterior scenes present a rush from the gathering crowd, police presence, and aural confusion. Lumet also refused to allow music into the film. “If the first obligation […] was to tell the audience that this event really happened, how could you justify weaving music in and out?” he wrote. Even the song that plays over the opening montage of city scenes, “Amoreena” by Elton John, sounds like a non-diegetic soundtrack until Lumet reveals its source in the getaway car and within the diegesis.

Lumet’s interest in the stranger-than-fiction reality of Dog Day Afternoon is only outperformed by his interest in his actors. Above all, there is Pacino, who is almost always onscreen with his sweaty, birdlike coif and restless eyes. In a method performance, Pacino turns Sonny into more than a bank robber. He doesn’t want to hurt anyone, he tells his captives, and it’s not just a line. While Sonny and Sal could have been well on their way, Sonny expends time to allow the head teller (Penelope Allen) to use the bathroom. He won’t lock the employees in the vault without air to breathe. He quickly forms an understanding with his hostages, some of whom seem to enjoy the experience and media attention—they watch themselves on TV, dance, laugh, and even practice spinning Sonny’s rifle. To be sure, Sonny is more complex than a mere hero or anti-hero. He’s also married to Angie (Susan Peretz), who didn’t come down to the bank because she “couldn’t get a babysitter” and nags him over the phone until he hangs up. But there are hints of Sonny’s instability beyond the criminal act at the film’s center. Leon and Angie both recount to police his angry outbursts and crazed behavior. Regardless, Sonny has our sympathy. Psychologists might argue that both the audience and the hostages suffer from Stockholm syndrome. That might be a stretch. If we don’t learn to love Sonny, we learn to understand him—and Lumet gives that same consideration to every character onscreen. His interest in the humanity of both crooks and cops, man and woman, straight and gay, remains constant. Everyone’s just trying to get through this exhaustive day.

After its release, Robin Wood noted that Dog Day Afternoon was “the first American commercial movie in which the star/identification figure turns out to be gay.” This fact was not lost on Lumet or his leading man. Pacino’s screen career had just launched a few years earlier, and the stage actor’s rise was meteoric. His appearances in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), Lumet’s Serpico (1973), and Coppola’s The Godfather Part II (1974) confirmed he was a formidable actor. Yet, he had reservations about playing Sonny in Dog Day Afternoon. He agreed to the role and then backed out several times, expressing concern about Sonny’s state of mind and queer identity. Eventually, he signed for the part. Even so, after rehearsals, Pacino asked Lumet and Pierson to come to his home the day before the production was slated to go before cameras. In a story from Maura Spiegel’s biography of Lumet, when they arrived, Pacino was acting like a dog, crawling around on all fours and barking. Worried that playing a queer man would tarnish his blooming career, Pacino pretended to go mad, hoping to be excused from the picture. However, Lumet saw through the dog routine and asked Pacino to put his anxieties into his performance. After all, Sonny must have similar feelings about robbing the bank. Pacino showed up for shooting as scheduled the next day.

After its release, Robin Wood noted that Dog Day Afternoon was “the first American commercial movie in which the star/identification figure turns out to be gay.” This fact was not lost on Lumet or his leading man. Pacino’s screen career had just launched a few years earlier, and the stage actor’s rise was meteoric. His appearances in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), Lumet’s Serpico (1973), and Coppola’s The Godfather Part II (1974) confirmed he was a formidable actor. Yet, he had reservations about playing Sonny in Dog Day Afternoon. He agreed to the role and then backed out several times, expressing concern about Sonny’s state of mind and queer identity. Eventually, he signed for the part. Even so, after rehearsals, Pacino asked Lumet and Pierson to come to his home the day before the production was slated to go before cameras. In a story from Maura Spiegel’s biography of Lumet, when they arrived, Pacino was acting like a dog, crawling around on all fours and barking. Worried that playing a queer man would tarnish his blooming career, Pacino pretended to go mad, hoping to be excused from the picture. However, Lumet saw through the dog routine and asked Pacino to put his anxieties into his performance. After all, Sonny must have similar feelings about robbing the bank. Pacino showed up for shooting as scheduled the next day.

Lumet filled the other roles with Off-Broadway actors and people who looked like they came from the streets of New York. Pacino pitched Lumet on casting John Cazale—the actor’s on-screen sibling in The Godfather—as Sal, the lumbering powderkeg whose eerie exterior calm hints at something sensitive and broken underneath. The director worried about Cazale being nearly 20 years older than his real-life counterpart, but he agreed to cast him after a single meeting. Cazale’s role would mark one of just five screen appearances for the actor, each in an iconic film. He died in 1978 from lung cancer caused by chain-smoking, and because of this, there’s a grim irony in his role as Sal, a character who refuses to smoke because he doesn’t “want the cancer.” The most challenging part to cast was Leon, the first openly trans character in a Hollywood film. Lumet auditioned various members of the gay community, including several drag performers. But the director found his Leon with Chris Sarandon, whose approach to the character avoided showy flamboyance in favor of emotional realism. Assistant director Burtt Harris recalled Sarandon’s approach: “‘All I gotta do is be in love with this guy, want to marry him, and get a sex change operation. Simple.’” Further downplaying the potential for sensationalism or exploitation, Lumet’s famous one-line direction to Sarandon was “a little less Blanche Dubois, a little more Queens housewife.”

Lumet’s drive toward “naturalism” in Dog Day Afternoon meant he relied on the actors to improvise more than in any other film to his name. Although Frank Pierson would go on to earn an Oscar for his screenplay, Lumet and his actors workshopped scenes during rehearsals and created spontaneous moments. The director often recorded these improvisations and rewrote scenes according to the actors’ ad-libbing. The key to their on-set improvisation was that each actor had thoroughly learned their character during the extensive rehearsals, allowing in-character instincts to take over. Among the most famous improvisations occurs when Sonny asks Sal which country he’d like to escape to in their plane. Sal replies, “Wyoming.” Lumet had to cover his mouth to silence a laugh and not ruin the take. Also improvised was Sonny’s line, “Attica! Attica!”—arguably the film’s most memorable scene—to whip up the crowd outside the bank. Sonny evokes the Attica prison massacre in 1971, in which authorities responded to a prolonged riot by gunning down prisoners, hostages, and guards, and afterward made white supremacist declarations. The assistant director whispered “Attica” to Pacino just before the cameras rolled and helped create one of the most iconic moments in all 1970s cinema. The simple one-word reference captures Sonny’s distrust of the police, who cruelly target people of color and the LGBTQ+ communities.

While Sonny fuels the crowd’s rage against the police, his audience fuels him. Dog Day Afternoon shows Sonny’s need to be seen, and to an extent, a growing tendency to acquire power by becoming “a star.” Note the scene when the pizza delivery boy hands over the pizzas to Sonny, then turns and declares, “I’m a star!” Years later, Pacino observed, “That was the first time that kind of recognition vis à vis TV and the real world was shown. In a way it was reality TV.” Similarly, Sonny has no power in life but attains it through the robbery. He feels beleaguered and stressed, struggling to find work and pay for Leon’s operation. He says to both of his wives, “I’m dying here.” Although he never intended the robbery to become a hostage situation, Sonny quickly goes from feeling like “a fuck-up and an outcast” to being empowered by his ability to give orders to the police. “Put those guns down!” he orders from outside the bank. Moretti reinforces the order, running at officers and shouting, “Holster those weapons!” The crowd recognizes that Sonny, an otherwise powerless bisexual man in a world that does not accept him, has seized control. They cheer him on: “We’re with you, Sonny!” And Sonny amplifies himself to give the crowd a show. In one scene, he tosses cash at the crowd, prompting a scramble for the loose bills and friction between the police and onlookers. The real-life bank robber, Wojtowicz, inspired Sonny’s characteristic need for attention. Screenwriter Frank Pierson interviewed Wojtowicz and described his behavior as “‘I’ve got to keep your attention because the moment you look away, I don’t exist anymore.’” Viewers can see Wojtowicz’s hunger for attention in Walter Stokman’s 2005 documentary about the real-life robbery, Based on a True Story, in which Wojtowicz inflates his importance over his celebrity: “Do you know how many thousands of people will come [to the film] just to see me?”

While Sonny fuels the crowd’s rage against the police, his audience fuels him. Dog Day Afternoon shows Sonny’s need to be seen, and to an extent, a growing tendency to acquire power by becoming “a star.” Note the scene when the pizza delivery boy hands over the pizzas to Sonny, then turns and declares, “I’m a star!” Years later, Pacino observed, “That was the first time that kind of recognition vis à vis TV and the real world was shown. In a way it was reality TV.” Similarly, Sonny has no power in life but attains it through the robbery. He feels beleaguered and stressed, struggling to find work and pay for Leon’s operation. He says to both of his wives, “I’m dying here.” Although he never intended the robbery to become a hostage situation, Sonny quickly goes from feeling like “a fuck-up and an outcast” to being empowered by his ability to give orders to the police. “Put those guns down!” he orders from outside the bank. Moretti reinforces the order, running at officers and shouting, “Holster those weapons!” The crowd recognizes that Sonny, an otherwise powerless bisexual man in a world that does not accept him, has seized control. They cheer him on: “We’re with you, Sonny!” And Sonny amplifies himself to give the crowd a show. In one scene, he tosses cash at the crowd, prompting a scramble for the loose bills and friction between the police and onlookers. The real-life bank robber, Wojtowicz, inspired Sonny’s characteristic need for attention. Screenwriter Frank Pierson interviewed Wojtowicz and described his behavior as “‘I’ve got to keep your attention because the moment you look away, I don’t exist anymore.’” Viewers can see Wojtowicz’s hunger for attention in Walter Stokman’s 2005 documentary about the real-life robbery, Based on a True Story, in which Wojtowicz inflates his importance over his celebrity: “Do you know how many thousands of people will come [to the film] just to see me?”

The scenes of Sonny outside, facing down hundreds of spectators and cops, have electric energy. The audience feels that charge, even while recognizing the situation has become unhinged, sometimes comically so. But Lumet also observes smaller moments with equal attention. After Sonny speaks with Leon on the phone, Lumet holds a close-up of Panico, whose sweaty and frantic energy, twitchy blinking, and facial ticks have been constant and exertive features until now. Then, for half a minute, Sonny sighs, wipes his brow, closes his eyes, lowers his head to cry, and then looks off, exasperated and trapped, his hair in mopish disarray. Lumet called it “Some of the best film acting I’ve ever seen.” It’s a moment that solidifies our identification with Sonny over, say, any of the cops who are often shown filling their faces with food or, in the FBI’s case, rigid and emotionless. And while most of Lumet’s direction could be called realistic and actor-focused, exceptions arise in his treatment of the film’s two gunshots: first, when Sonny shoots out a window at the bank’s rear entrance, and second when FBI Agent Murphy (Lance Henrikson) shoots Sal in the head at the airport. Both gunshots are followed by quick montages of chaotic reactions, with millisecond cutting by editor Dede Allen. People scatter, bank employees scream, police raise their weapons, the crowd rushes away, and everyone takes cover. These montages contain the same kineticism in Pacino’s performance, among the actor’s very best and dimensional.

To be sure, Lumet’s interest in “naturalism” resulted in flesh-and-blood characters and avoided many clichés that Hollywood often uses to represent queer characters on the screen. However, Pacino later demanded changes to the screenplay to limit the number of scenes in a queer context. These included removing a scene from the script involving Sonny and Leon’s wedding, which was to feature Sonny in his military garb and Leon in a wedding dress. Instead, a photo of Leon in his wedding dress appears on a television broadcast. Lumet also removed a goodbye kiss at the bank, replacing the scene with the heartbreaking farewell phone call between Sonny and Leon—during which the actors spoke on an actual phone call for the sake of authenticity. The original scenes, Lumet felt, would alienate the predominantly heterosexual audience of 1975. Despite the changes to accommodate viewers who were not prepared to see a same-sex wedding or kiss in a major motion picture, Lumet also sought approval from the LGBTQ+ community. He consulted with the Gay Activists Alliance, a group founded in New York just a few months after the Stonewall riots. The Alliance gave their stamp of approval, and members of the gay liberation movement served as crowd extras outside the bank, chanting, “Out of the closet and into the street!”

Lumet’s humanist treatment of Sonny and Leon underscores what scholar Fredric James described as a “new visibility of something more fundamental in what might otherwise simply seem the background itself.” The new agency and emphasis on countercultural figures extend beyond the queer community. Consider how certain bank employees gradually begin to understand and empathize with Sonny as a figure of rebellion against authority, giggling when other employees or their manager question Sonny’s use of “language.” Sonny’s underdog role in the tragedy of Dog Day Afternoon makes his story sympathetic to the average viewer. A queer man becomes no longer a figure of scorn and ridicule—as is often the case in Hollywood films of this era—nor a stereotype, but someone worthy of compassion. The film never makes Sonny’s sexuality an issue. It’s not an issue for Sonny, who remarks, “It’s just a freak show to them anyway. It don’t matter.” And it’s not an issue for Lumet, who never overemphasizes the point or directs either Pacino or Sarandon to give a camp performance. Sarandon noted in an interview for a making-of documentary that the film “wasn’t about a drag queen and his boyfriend” but about “trying to come to grips with what is wrong in their relationship.” Although cops snicker and make cruel remarks amongst themselves, Sonny and Leon’s evident affection for one another is treated with tenderness by Lumet and his actors. And when Sonny dictates his will, he avows that he loves Leon “more than any man has loved another man in all eternity,” and the viewer’s heart cannot help but ache.

Lumet’s humanist treatment of Sonny and Leon underscores what scholar Fredric James described as a “new visibility of something more fundamental in what might otherwise simply seem the background itself.” The new agency and emphasis on countercultural figures extend beyond the queer community. Consider how certain bank employees gradually begin to understand and empathize with Sonny as a figure of rebellion against authority, giggling when other employees or their manager question Sonny’s use of “language.” Sonny’s underdog role in the tragedy of Dog Day Afternoon makes his story sympathetic to the average viewer. A queer man becomes no longer a figure of scorn and ridicule—as is often the case in Hollywood films of this era—nor a stereotype, but someone worthy of compassion. The film never makes Sonny’s sexuality an issue. It’s not an issue for Sonny, who remarks, “It’s just a freak show to them anyway. It don’t matter.” And it’s not an issue for Lumet, who never overemphasizes the point or directs either Pacino or Sarandon to give a camp performance. Sarandon noted in an interview for a making-of documentary that the film “wasn’t about a drag queen and his boyfriend” but about “trying to come to grips with what is wrong in their relationship.” Although cops snicker and make cruel remarks amongst themselves, Sonny and Leon’s evident affection for one another is treated with tenderness by Lumet and his actors. And when Sonny dictates his will, he avows that he loves Leon “more than any man has loved another man in all eternity,” and the viewer’s heart cannot help but ache.

Lumet may have matter-of-factly portrayed LGBTQ+ characters, but few critics, apart from Jameson and Wood, confronted that context upon the film’s release in September 1975 beyond remarking about its inclusiveness. Only later would Dog Day Afternoon be recognized for its groundbreaking portrayal of LGBTQ+ characters in a straightforward manner. But those versed in Lumet and his career should not have been surprised. His lifelong liberal politics ranged from secretly working with blacklisted writers on his television productions in the 1950s to his financial support of the American Civil Liberties Union, the Southern Poverty Law Center, and Amnesty International. His interest was in human rights and justice, both legal and social. This is evidenced in his many pictures about police corruption and abuses of power, including themes of racism, as in 12 Angry Men and Q&A (1988). Regardless of subject matter that may have been considered taboo in the ’70s, Dog Day Afternoon became the year’s fourth highest grosser after Jaws, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and Shampoo. It received six Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor for Pacino, Best Supporting Actor for Sarandon, Best Editing, and Best Original Screenplay. Pierson won the film’s only Oscar for his screenplay, despite the heavy improvisations and credited Life magazine source material. The film has since gone on to be considered a cherished classic.

If Dog Day Afternoon’s many terrific performances, immersive vérité-style filmmaking, and unpredictable scenario preserve its place in the canon of great American films of the 1970s, its unembellished portrait of LGBTQ+ characters keeps the film in the contemporary conversations about representation in cinema. Ever a humanist whose outspoken support of left-wing causes saturate his films, Lumet did not make the film as an agenda piece; rather, he recognized the drama in this real-life story and saw its potential to “reveal something about yourself and others.” In this, Lumet exposed mainstream moviegoers to another world, and this pointedly queer subject played by Al Pacino remains center stage for most of the film, his psychology on urgent display from start to finish. Sonny’s openness presents a sharp contrast to the stone-faced exterior of the FBI agents and the cheap manipulations by Det. Moretti. By not making Sonny’s identity the film’s subject, Lumet effectively normalizes it in a manner few other Hollywood films have ever achieved without some measure of didacticism. In a career of telling New York stories, Lumet’s approach to Dog Day Afternoon remains his most earnest and lasting commentary on the messiness and sublime complexity of human beings.

(Editor’s Note: This essay was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your continued support, Mark!)

Bibliography:

Brown, Christopher R. “Homosexuality in Dog Day Afternoon (1975): Televisual Surfaces and a ‘Natural’ Man.” Film Criticism, vol. 37, no. 1, 2012, pp. 35–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24777848. Accessed 15 June 2022.

Bouzereau, Laurent. “Dog Day Afternoon: After the Filming.” DVD. Warner Bros., 2006.

—. “Dog Day Afternoon: Casting the Controversy.” DVD. Warner Bros., 2006.

—. “Dog Day Afternoon: The Story.” DVD. Warner Bros., 2006.

—. “Dog Day Afternoon: Recreating the Facts.” DVD. Warner Bros., 2006.

Jameson, Fredric. “Class and Allegory in Contemporary Mass Culture: Dog Day Afternoon as a Political Film.” College English, vol. 38, no. 8 (April, 1977), pp. 843-859.

Lumet, Sidney. Making Movies. A.A. Knopf, 1995.

Macias, Anthony. “Gay Rights and The Reception of Dog Day Afternoon (1975).” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 48 no. 1, 2018, p. 45-56

Pacino, Al. Al Pacino in conversation with Lawrence Grubel. Simon & Schuster, 2006.

Spiegel, Maura. Sidney Lumet: A Life. St. Martin’s Press, 2019.

Wood, Robin. “American Cinema in the ’70s: Dog Day Afternoon.” Movie, no. 23 (Winter 1976-1977), pp. 33-36.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review