The Definitives

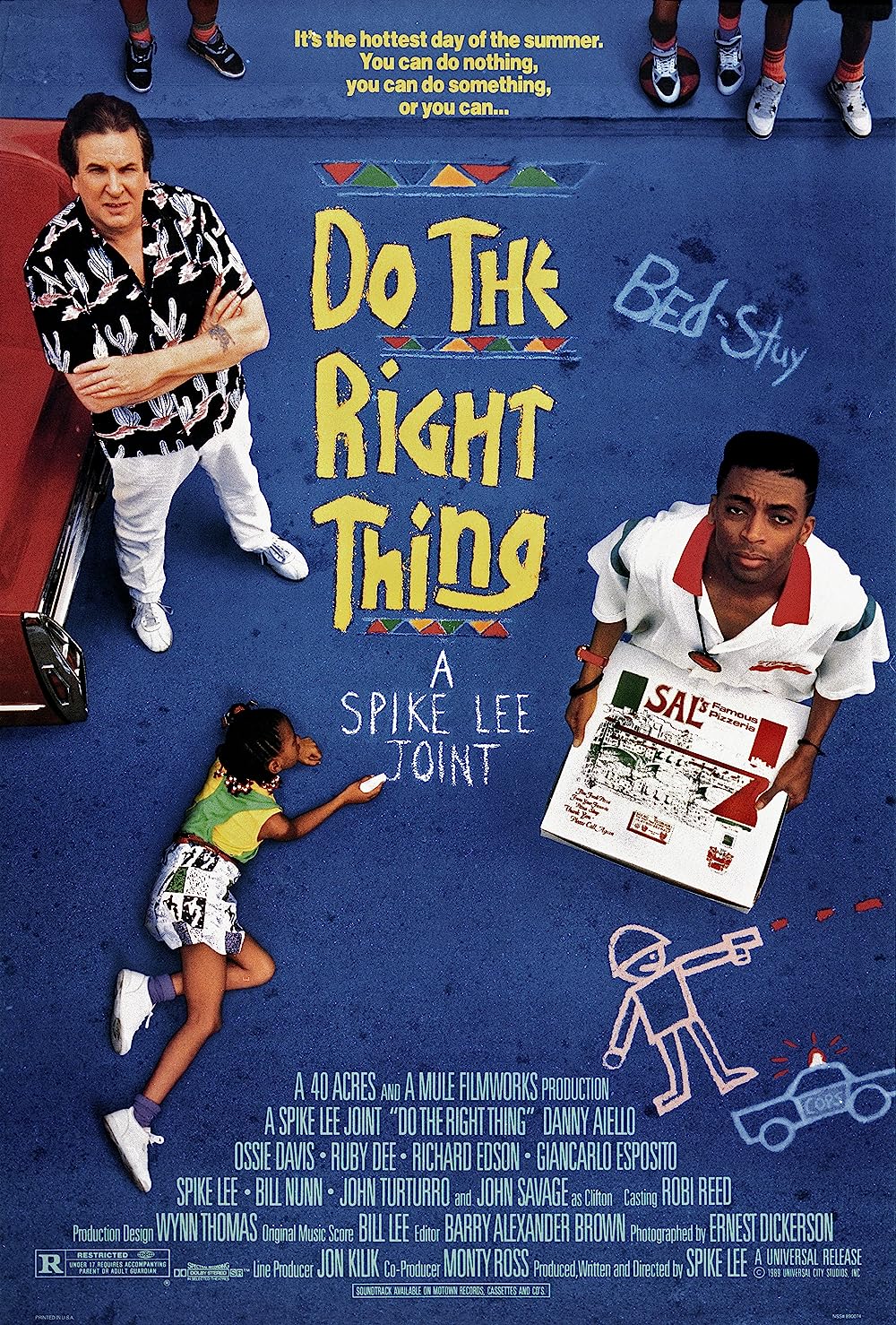

Do the Right Thing (1989)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

“Wake up!” announces Samuel L. Jackson’s Mister Señor Love Daddy, a disc jockey in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, the setting of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. The first line, which is also the last line of his previous feature from 1988, School Daze, is meant to incite contemplation and discussion rather than supply an unequivocal lesson. In Do the Right Thing, the DJ’s morning address follows the stagelike title sequence in which Rosie Perez dances to a Public Enemy song that encourages listeners to “fight the power.” Within its first moments, Do the Right Thing establishes Lee’s dialectical intention to pose unanswered questions by exposing the artifice of cinema and engaging the critical viewer. The film does not explain what exactly its audience should wake up from, what power we should be fighting, or what constitutes doing the right thing. But Lee’s aesthetically rich work of art uses a distancing effect to incite critical viewership. His technique draws attention to his stylistic choices: the theatrical quality of the drama and staging, the unforgettable moments that nonetheless interrupt the narrative, the choices of actors and their performative styles, and scenes that amount to an allegory in the manner of a Greek tragedy. Together these elements arouse contemplation about the intractable dilemmas of race and ethnicity in American culture. And given Lee’s refusal to provide easy solutions to enduring problems or pacify our emotions with some measure of closure, Do the Right Thing endures as an essential work of cultural introspection.

Set on the hottest day of the summer, Do the Right Thing frames the rise of racial tensions between an African American community and an Italian American business. Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, long-established in the Bed-Stuy neighborhood, is owned and operated by the venerable entrepreneur Sal (Danny Aiello). His sons, the unapologetically racist and angry Pino (John Turturro), and Pino’s bullied younger brother Vito (Richard Edson), also contribute to the parlor. Though, Pino no longer wants to work there as he despises the local African American community. Their sole employee, the slacking delivery boy Mookie (Lee), spends much of his time wandering the neighborhood or attempting to reconcile with Tine (Rosie Perez), the mother of his child. The day’s conflict begins when a young Black man named Buggin Out (Giancarlo Esposito) demands that Sal include some African American faces on his establishment’s “Wall of Fame,” which features exclusively Italian American actors and performers. Sal refuses, arguing that it’s his restaurant, and he will display whomever he chooses. Buggin Out wants Sal to acknowledge that he’s in a neighborhood populated almost entirely by people of color, and since without them Sal’s would not exist, he should show his respect. When Sal refuses, Buggin Out attempts to organize a neighborhood boycott.

At first, the boycott is a futile effort given Buggin Out’s verbose anger and the neighborhood’s impression of Sal’s as a community staple. But the conflict, perpetuated by several other tensions on the hot Bed-Stuy streets, continues to escalate throughout the long summer day into a more serious tension. Buggin Out gains a small following. The intellectually disabled Smiley (Roger Gueneveur Smith), who makes rounds through Bed-Stuy to sell postcards of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, joins the mission after Pino insults him. The neighborhood’s unrelenting rap enthusiast, Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), walks the streets with his boombox thumping a constant stream of Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” on repeat (“I don’t like nothin’ else,” he admits). Radio Raheem, having already been asked to shut off his music while inside Sal’s Pizzeria earlier that day, joins Buggin Out and Smiley, and provokes Sal and his sons by refusing to turn off his music. Sal responds, shouting over the music in a racist outburst that culminates with Sal’s destruction of Radio Raheem’s boombox. A fight breaks out, and a crowd converges, enraged at Sal’s racist behavior. The police arrive, restraining not Sal, the instigator of violence, but Radio Raheem, whom they strangle to death in a chokehold. The police quickly remove the body and leave the scene. At this, Mookie picks up a metal garbage can from the street and throws it through Sal’s window, inciting a full-scale riot that leaves Sal’s Famous Pizzeria in flames.

At first, the boycott is a futile effort given Buggin Out’s verbose anger and the neighborhood’s impression of Sal’s as a community staple. But the conflict, perpetuated by several other tensions on the hot Bed-Stuy streets, continues to escalate throughout the long summer day into a more serious tension. Buggin Out gains a small following. The intellectually disabled Smiley (Roger Gueneveur Smith), who makes rounds through Bed-Stuy to sell postcards of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, joins the mission after Pino insults him. The neighborhood’s unrelenting rap enthusiast, Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), walks the streets with his boombox thumping a constant stream of Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” on repeat (“I don’t like nothin’ else,” he admits). Radio Raheem, having already been asked to shut off his music while inside Sal’s Pizzeria earlier that day, joins Buggin Out and Smiley, and provokes Sal and his sons by refusing to turn off his music. Sal responds, shouting over the music in a racist outburst that culminates with Sal’s destruction of Radio Raheem’s boombox. A fight breaks out, and a crowd converges, enraged at Sal’s racist behavior. The police arrive, restraining not Sal, the instigator of violence, but Radio Raheem, whom they strangle to death in a chokehold. The police quickly remove the body and leave the scene. At this, Mookie picks up a metal garbage can from the street and throws it through Sal’s window, inciting a full-scale riot that leaves Sal’s Famous Pizzeria in flames.

Lee structures Do the Right Thing as a philosophical argument whose lessons are ambiguous and whose methods spur the viewer into a dialogue. His dialectical intentions begin with the Universal Pictures logo in the opening, over which a saxophone plays the first bars of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” sometimes called “The Black National Anthem” given its author, NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson. In the next moment, Perez delivers her pulsating dance of coded gestures and shadowboxing to Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” a rap song that urgently challenges the so-called progress made to end racism in the United States during the Civil Rights Movement, and then demands action. The two songs are representative of the many strains of back-and-forth viewpoints present throughout the film. The viewer can understand Buggin Out’s opinion that Sal should recognize his place in the Black community by including people of color on his Wall of Fame, just as the viewer can accept Sal’s right as a business owner to decide how to decorate the interior of his restaurant. The way Radio Raheem, Buggin Out, and Smiley provoked Sal may not have been wise, but then Sal’s use of racial epithets and a baseball bat to smash Radio Raheem’s boombox escalated matters to violence. Almost every confrontation in the film can be read from multiple perspectives. And after the sobering conclusion, Lee offers two quotations, one from Martin Luther King and another from Malcolm X, each outlining their oppositional views on the use of violence to solve matters of racial intolerance. He sees the benefits and dangers of both violence and peaceful protest, and rather than declare his faithfulness to one or the other, he does something far more dangerous by calling on the audience to answer his dialectical prompt.

Lee’s quintessentially American brand of filmmaking springs from his cultural and ethnic background, and from there, he focuses on an equally specific range of themes, stylistic choices, and social values in his work. Lee was born in Atlanta in 1957, but his family moved to Brooklyn when he was still an infant. His mother taught African American art and literature while his father worked as a jazz musician. As a boy, he explored his neighborhood with a Super 8 camera and quickly realized what he would do with his life. He completed his first short film, Last Hustle in Brooklyn, at 20, as an undergraduate at Morehouse College. He later graduated from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts in 1982, and his thesis film, Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads, earned the Student Academy Award. In an interview with Delroy Lindo, the star of Lee’s Crooklyn (1994) and Clockers (1995), the director said that he wanted to film “the richness of Africa American culture that I can see, just standing on the corner, or looking out my window every day.” But Lee has always been concerned with more than representations of contemporary New York life in his resident neighborhood. Ed Guerrero called him an “issues-oriented” filmmaker, noting that he often frames his films around a sociopolitical concern or historical event. Lee does not work in a single genre or style. The defining quality of his cinema is his willingness to engage with the social dynamics of race and culture, most often through the lens of African American identity, history, and representation.

Lee’s Do the Right Thing was directly inspired by several real-life incidents that permeated the larger cultural and historical context of the 1980s, specifically in New York City. Above all, he used the murder of Michael Griffith in 1986, a Black man from Bed-Stuy who was chased and beaten to death by a gang of white men. After their car broke down in the middle of the night, Griffith and his two friends walked three miles before stopping at the New Park Pizzeria in the mostly white Howard Beach neighborhood of Queens. They asked to use the phone but were told none was available, so they sat to have a slice. While resting, someone called the police about “three suspicious black males” in the area. The police came and went without incident. When the three men left the pizza parlor, they were met by around ten white men armed with bats, shouting, “You don’t belong here!” First, the mob hurled racial slurs, then they attacked and proceeded to chase the young Black men through the streets of Brooklyn. For several blocks, Griffith and his friends sustained beatings, until Griffith was struck by a car in his escape, his skull crushed. The pizzeria and Bed-Stuy neighborhood in Lee’s film were apparent nods to Michael Griffith’s death, a killing that New York mayor Ed Koch compared to a Deep South lynching.

Lee’s Do the Right Thing was directly inspired by several real-life incidents that permeated the larger cultural and historical context of the 1980s, specifically in New York City. Above all, he used the murder of Michael Griffith in 1986, a Black man from Bed-Stuy who was chased and beaten to death by a gang of white men. After their car broke down in the middle of the night, Griffith and his two friends walked three miles before stopping at the New Park Pizzeria in the mostly white Howard Beach neighborhood of Queens. They asked to use the phone but were told none was available, so they sat to have a slice. While resting, someone called the police about “three suspicious black males” in the area. The police came and went without incident. When the three men left the pizza parlor, they were met by around ten white men armed with bats, shouting, “You don’t belong here!” First, the mob hurled racial slurs, then they attacked and proceeded to chase the young Black men through the streets of Brooklyn. For several blocks, Griffith and his friends sustained beatings, until Griffith was struck by a car in his escape, his skull crushed. The pizzeria and Bed-Stuy neighborhood in Lee’s film were apparent nods to Michael Griffith’s death, a killing that New York mayor Ed Koch compared to a Deep South lynching.

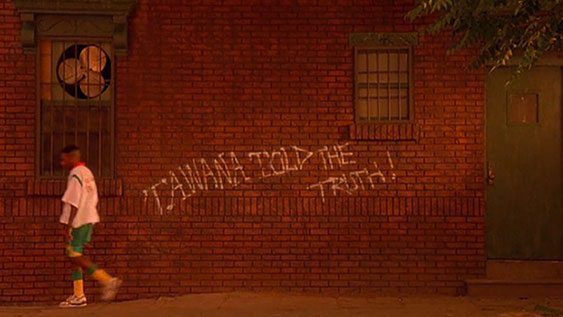

Do the Right Thing was released at a time when hostilities involving race and difference flared, rippling out from New York City across the entire country. A series of racially charged killings of African American men—Willie Turks in 1982, Michael Stewart in 1983, and Yusuf Hawkins in 1989—were carried out by mobs of white people in New York, heightening racial tensions. Lee references the highly publicized Tawana Brawley rape case, where the 15-year old girl accused four white men of raping her over several days and leaving her body marked with racial epithets in November 1987. Although the allegations were contested in court, one scene in the film features “Tawana told the truth” written in graffiti on a wall. The shooting of Eleanor Bumpers by white NYPD officers during an eviction process in 1984 also fueled the tension. And just before the film’s release, the sexual assault of Trisha Meili in April 1989 led to the Central Park Five scandal, where African American and Hispanic teenagers were coerced into confessions of rape and assault, only to be exonerated much later after the true perpetrator confessed in 2001. For much of this, Lee blamed the policies of Ed Koch, and the director included the words “Dump Koch” in the background of another scene. The voting public did just that when they elected David Dinkins over Koch in 1990. These interwoven issues of race, crime, and accusation saturated the cultural discourse that inspired Lee’s film, making Do the Right Thing seem of the moment.

The film premiered at the Canned Film Festival in May 1989 and remains his most widely esteemed and debated work. It received an impressive number of awards and nominations after its release, including a nomination for the Palme d’Or and an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay. Lee and his cast also won several awards. These include the Los Angeles Film Critics Association’s prizes to Lee for his direction, Lee’s father Bill for composing the score, Aiello for best supporting actor, and the top prize for best picture. Several other critical associations and film institutions gave it honors, whereas the mainstream Academy Awards issued their statues to Driving Miss Daisy, a film whose discussion of race relations limits itself to a white audience. Whereas the Oscar for Best Picture went to Driving Miss Daisy, a film that has been largely forgotten in the decades since its release, Lee’s film continues to be at the forefront of the cinematic discussion about representation, race, and unanswerable questions about America and its history. It also took only ten years for the Library of Congress to add Do the Right Thing to the National Film Registry as a work that demands cultural preservation. Driving Miss Daisy has yet to make the list.

After its Cannes premiere, Do the Right Thing sparked impassioned reactions and debate about what Lee was trying to achieve. Countless features in The New York Times, Newsweek, and American Film; primetime specials on Nightline and The Oprah Winfrey Show; and public discourse debated the intentions and meaning of Lee’s film. Many at the time, such as Joe Klein in New York magazine, worried that Do the Right Thing would cause the type of riot dramatized in its climax. Commentators questioned the summer release in the United States that threatened to mirror the boiling hot conflict of the film, suggesting that young Black men would follow Mookie’s example and take to the streets, causing a race riot. They remarked on how unrealistic the film seemed, such as Richard Corliss in Time, who, demonstrating his own prejudices and assumptions, described the Bed-Stuy neighborhood as a type of Sesame Street because it was unnaturally devoid of “crack dealers, hookers or muggers.” Articles accusing the film of fascism and racism were almost as frequent as those celebrating the arrival of an African American independent filmmaker with the capacity to engage viewers across a wide array of racial and class identities. Lee was championed as a new voice for Black audiences, standing at the forefront of an emergent New Wave of Black filmmakers who grew up during the Civil Rights Movement and began to reach mainstream audiences with their films. Do the Right Thing went beyond the limited viewership of his first two films, She’s Gotta Have It (1986) and School Daze, drawing more attention from the media and a broader audience with its wider release plan under Universal Pictures.

After its Cannes premiere, Do the Right Thing sparked impassioned reactions and debate about what Lee was trying to achieve. Countless features in The New York Times, Newsweek, and American Film; primetime specials on Nightline and The Oprah Winfrey Show; and public discourse debated the intentions and meaning of Lee’s film. Many at the time, such as Joe Klein in New York magazine, worried that Do the Right Thing would cause the type of riot dramatized in its climax. Commentators questioned the summer release in the United States that threatened to mirror the boiling hot conflict of the film, suggesting that young Black men would follow Mookie’s example and take to the streets, causing a race riot. They remarked on how unrealistic the film seemed, such as Richard Corliss in Time, who, demonstrating his own prejudices and assumptions, described the Bed-Stuy neighborhood as a type of Sesame Street because it was unnaturally devoid of “crack dealers, hookers or muggers.” Articles accusing the film of fascism and racism were almost as frequent as those celebrating the arrival of an African American independent filmmaker with the capacity to engage viewers across a wide array of racial and class identities. Lee was championed as a new voice for Black audiences, standing at the forefront of an emergent New Wave of Black filmmakers who grew up during the Civil Rights Movement and began to reach mainstream audiences with their films. Do the Right Thing went beyond the limited viewership of his first two films, She’s Gotta Have It (1986) and School Daze, drawing more attention from the media and a broader audience with its wider release plan under Universal Pictures.

Actually, it’s a small miracle that a Hollywood studio distributed Do the Right Thing. Most studios, especially in the 1980s, maintained an aversion to films that rested on ambiguity, polemical ideologies, or challenged widespread views about American identity. Hollywood, too, rarely made films about issues of race and difference, and their conflicted place in the fabric of American history and social power structures. Lee’s film goes against the usual Hollywood production’s push toward entertainment-first and commercial certainty, challenging the relatively moderate limits of the usual political liberalism of Hollywood. Though historically Hollywood productions have used ambiguity and left-leaning ideologies, rarely does a studio film make an unwavering statement, so as not to isolate a segment of the market and, thus, limit the commercial appeal. Then again, the film industry of the 1980s viewed African American audiences as a niche market, and so Black filmmakers and stories were marginalized because such material rarely had crossover appeal. Lee had his own obstacles to overcome. His first two films were profitable but earned him a reputation, which he described as “a wild-eyed black militant, a baby Malcolm X” that flashed a warning sign to Hollywood executives.

When Lee was shopping the script to various studios, Paramount Pictures was the first to show interest; however, they demanded that Lee make alterations to the material to suit their audience. “Paramount wanted Mookie and Sal to hug at the end of the movie,” Lee told The Hollywood Reporter. Lee expanded in his journal, “They are convinced that black people will come out of the theaters wanting to burn shit down.” When Lee refused to tame the film’s central conflict, the studio canceled negotiations. After talks with Paramount ended, Touchstone Pictures also turned down the production. Lee felt he had to combat how he was perceived in Hollywood at the time, that any Black man who was not accommodating to white interests was deemed “difficult” and would not align with studio considerations. Still, Universal Pictures ultimately agreed to finance Do the Right Thing. Head of production Tom Pollack maintained it was not because they wanted to release social issue films, which was the perception after they distributed Martin Scorsese’s controversial The Last Temptation of Christ in 1988. Rather, Pollack noted their interest in Lee’s film was primarily a matter of recognizing its potential to make money from a relatively inexpensive $6.5 million budget (School Daze cost the same and earned over $14 million). After Pollack agreed to finance the picture, Lee shot for 40 days and, by the end of its theatrical run, Do the Right Thing earned $27 million at the domestic box office. Universal would distribute several “Spike Lee Joints” throughout the 1990s.

The film is a lightning bolt not only for its affront discussion of American race relations but also for its formal bravado that places its themes on a stage. Working alongside cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, costume designer Ruth E. Carter, and production designer Wynn Thomas, Lee creates an aesthetic that, despite his film tackling real-life issues of race in an urban landscape, is accented by a stagelike quality. It is Do the Right Thing’s theatrical characteristics, both dramatically and formally, that naturally welcome investigation from the viewer as to their meaning. The events, as discussed, demand the viewer to weigh the racial and ethical components at work in the story. Even the film’s 24-hour period seems to encapsulate the story on stage, drawing a considerable attention to the drama and impregnating the material with meaning. But the theatrical quality of the actors, setting, lighting, and color each have a lesson beneath them as well. Lee evokes the theater from the opening credits, when Perez dances to “Fight the Power” on a stage, in front of a flat city street façade lit with theater gels of red and orange—colors that anticipate the pervasive hottest-day-of-summer element running through the film. Elsewhere, Lee uses a veritable Greek chorus of three men on the corner diagonally opposite of Sal’s. ML (Paul Benjamin), Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison), and Sweet Dick Willie (Robin Harris) survey the neighborhood and engage in idle chatter, often remarking on and contextualizing the film’s themes.

The film is a lightning bolt not only for its affront discussion of American race relations but also for its formal bravado that places its themes on a stage. Working alongside cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, costume designer Ruth E. Carter, and production designer Wynn Thomas, Lee creates an aesthetic that, despite his film tackling real-life issues of race in an urban landscape, is accented by a stagelike quality. It is Do the Right Thing’s theatrical characteristics, both dramatically and formally, that naturally welcome investigation from the viewer as to their meaning. The events, as discussed, demand the viewer to weigh the racial and ethical components at work in the story. Even the film’s 24-hour period seems to encapsulate the story on stage, drawing a considerable attention to the drama and impregnating the material with meaning. But the theatrical quality of the actors, setting, lighting, and color each have a lesson beneath them as well. Lee evokes the theater from the opening credits, when Perez dances to “Fight the Power” on a stage, in front of a flat city street façade lit with theater gels of red and orange—colors that anticipate the pervasive hottest-day-of-summer element running through the film. Elsewhere, Lee uses a veritable Greek chorus of three men on the corner diagonally opposite of Sal’s. ML (Paul Benjamin), Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison), and Sweet Dick Willie (Robin Harris) survey the neighborhood and engage in idle chatter, often remarking on and contextualizing the film’s themes.

Structurally and visually, Do the Right Thing alternates among the Bed-Stuy characters, building through a dialectic the tensions and uncertainties that charge Lee’s situations and themes. The rhythm of the film’s arrangement has a theatrical quality, as though the entire neighborhood was the stage and, from scene to scene, Lee dims the lights on one area and illuminates them on another. It’s a film comprised of intervals and interruptions, asides and isolated moments. Lee does not follow a single character for long periods of the film. His drama alternates from individual scenes with Mookie to Sal to Buggin Out to children on the street cooling down in an open fire hydrant. The transitions seldom occur through abrupt cutting, but rather as Dickerson’s fluid camera movements track one scene and then, as another character enters from elsewhere in the neighborhood, the camera reconfigures its attention. Within a given scene, however, Lee often alternates between quarreling characters in a mirroring technique of editing that emphasizes the conflict. The harder the cut, the more intense the argument. When Buggin Out first enters Sal’s early in the film, Lee frames his debate with Sal about the cost of extra cheese, a relatively mild topic of contention, with both characters in the same shot. A moment later as their argument about Sal’s “Wall of Fame” heats up, the cutting becomes a sharper back-and-forth with a cut between each response, representing their opposition since the conflict is more serious. Lee uses these visual rhythms to underscore the connections and breaking points between people of Bed-Stuy.

Disjointed as this may feel at times, Lee ensures that every interval leads to something more in the overall drama of the film. For instance, several scenes involving the Korean store owner Sonny (Steve Park) and his wife Kim (Ginny Yang), and their interactions with more prominent characters, supply an unmistakable arc. In an early sequence involving the Greek chorus, ML bickers about the presence of the Korean grocer in the Black neighborhood: “I betcha they haven’t been a year off da motherfucking boat before they opened up their own place.” Sweet Dick Willie refuses to listen, saying “you got off the boat too,” before sauntering over to get a beer from the grocer. In another scene, Radio Raheem has a tense exchange with Sonny and Kim over batteries for his boombox and the language barrier that prevents him from getting the twenty “D” Energizers he needs. The initial impression of the Korean family in Bed-Stuy is one of animosity; however, the African American locals begin to identify with the Korean Americans, relating to them as similarly displaced people—the African Americans by slavery, the Koreans by emigration. When, in the climactic scene, the rioters enraged over Radio Raheem’s death direct their rage at the Korean grocery store, ML turns from Sal’s to Sonny and shouts, “Your turn, fucker!” But Sonny declares in broken English, “I no White! I Black! You. Me. Same!” The rioters accept this and refrain from continuing their attack.

Do the Right Thing also maintains provocative, Brechtian scenes that call attention to their presence in the drama. After one of many mirrored arguments between Mookie and Pino, Lee abruptly cuts into a montage of racial slurs. The sequence alternates between individuals of varied race and ethnicity—from Mookie to Pino, then to a Puerto Rican, a white cop, and the Korean grocer—as the frame pushes in, and they issue a tirade of racist remarks directly into the camera. Each character unloads against their chosen racial other. Mookie calls Pino a “Dago, wop, garlic-breath, guinea” and Pino responds with a string of insults that ends on “go back to Africa.” And so on. Through the bigoted sequence, Lee exposes the larger issues of racism that seep into an array of races and ethnicities, complicating Do the Right Thing’s overarching racial binarism between the owners of the Italian American pizzeria and the predominantly African American neighborhood. Visually, the sequence snaps the viewer out of the drama, just as the heat and tension have snapped these characters out of their social disguise to reveal the repressed stereotypes each group maintains about one another. At the same time, it shows how racism spreads from the individual, interpersonal conflicts to larger assumptions and prejudices. The sequence is suddenly interrupted by Mister Señor Love Daddy, who once more serves as the mouthpiece of the film and announces to the camera, as only Jackson can, an intense directive to the racially charged combatants: “Hold up! Time out! Time out! Y’all take a chill! Ya need to cool that shit out!”

Do the Right Thing also maintains provocative, Brechtian scenes that call attention to their presence in the drama. After one of many mirrored arguments between Mookie and Pino, Lee abruptly cuts into a montage of racial slurs. The sequence alternates between individuals of varied race and ethnicity—from Mookie to Pino, then to a Puerto Rican, a white cop, and the Korean grocer—as the frame pushes in, and they issue a tirade of racist remarks directly into the camera. Each character unloads against their chosen racial other. Mookie calls Pino a “Dago, wop, garlic-breath, guinea” and Pino responds with a string of insults that ends on “go back to Africa.” And so on. Through the bigoted sequence, Lee exposes the larger issues of racism that seep into an array of races and ethnicities, complicating Do the Right Thing’s overarching racial binarism between the owners of the Italian American pizzeria and the predominantly African American neighborhood. Visually, the sequence snaps the viewer out of the drama, just as the heat and tension have snapped these characters out of their social disguise to reveal the repressed stereotypes each group maintains about one another. At the same time, it shows how racism spreads from the individual, interpersonal conflicts to larger assumptions and prejudices. The sequence is suddenly interrupted by Mister Señor Love Daddy, who once more serves as the mouthpiece of the film and announces to the camera, as only Jackson can, an intense directive to the racially charged combatants: “Hold up! Time out! Time out! Y’all take a chill! Ya need to cool that shit out!”

The racial slur sequence is just one of many Brechtian flourishes, where Lee breaks from the narrative momentum to face the viewer. Another moment features Radio Raheem performing a “Love and Hate” monologue to Mookie during their brief encounter in the street. Raheem wears large gold rings, almost brass knuckles, with the words “LOVE” and “HATE” spelled out on the right and left hand, respectively. He proceeds to tell a mythical story, represented as Raheem shadow boxes toward the camera, each punch marking how either Love or Hate has the advantage in their ongoing battle, until finally the Hate is “KO’ed by Love.” Lee borrowed the moment from Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955), featuring Robert Mitchum as a murderous preacher with the words “LOVE” and “HATE” tattooed on his hands. Mitchum’s Rev. Harry Powell tells “the story of good and evil” in a writhing, expressive display in which his fingers are interlocked, and the sequence exemplified that film’s storybook conflict between the evil preacher and the innocent children he sought to kill. In Do the Right Thing, the monologue places Raheem at the center of the film’s conflict between love and hate, echoed by the philosophies of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X quoted at the film’s conclusion. Caught between these two opposing views, Raheem becomes a victim of the conflict at the climactic scene, marshaling the neighborhood and the viewer into introspection. As a character who teaches a lesson in the middle of the film, his death becomes the catalyst for another type of lesson in the finale whose interpretation is far less apparent than the one symbolized in his monologue.

Although Lee never breaks the fourth wall, he offers, in a manner that addresses the spectator, scenes that call attention to their uniqueness and placement within the overall film as emblematic of Do the Right Thing’s persistent themes. When the frame rushes toward each participant in the racial slur sequence, these characters unleash their discriminating remarks on each other. But Lee has framed them as though they are vented directly to the viewer. Similarly, Dickerson’s handheld camera faces Raheem during the “Love and Hate” monologue, and though the shot could be interpreted as being from Mookie’s perspective, Lee seems to want the audience to consider Raheem’s words outside of the film’s surface context. Along with the presence of Mister Señor Love Daddy, the Greek chorus on the corner, and even the violent climax of the film, Lee frees himself from the constraints of cinematic realism and engages in a form of theatricality, wherein the characters and, perhaps most importantly the violence, occurs on a performative and edifying platform. The violence of the finale functions as a highpoint to the emotional trajectory of the film, but it also represents the meeting of several conflicting views that are neither resolved within the story nor by lessons of the film. These theatrical moments in the film’s discourse become a strategy through which Lee demands a dialectical and not purely emotional outcome.

Lee’s dialectical intentions in both form and function are suffused with rich intertextuality that informs his casting and the direction of his actors, and it remarks on the history of race relations in America. Such choices appear in his casting of the Bed-Stuy elders, Da Mayor and Mother Sister, played by Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, the real-life couple whose activism and participation in the Civil Rights Movement goes back to the 1950s. In a 2018 profile in The New York Times, the couple was described as “stalwarts of the civil rights movement who navigated the sometimes contentious lines dividing different parts of the broader black freedom struggle.” Married in 1948, Davis and Dee starred in several Broadway productions together, including the original 1959 production of A Raisin in the Sun. Over the years, the couple continued to act together, but they also became voices in the sociopolitical discussions of the day as they made speeches, wrote articles, and performed in roles that advanced African American identity in the cultural consciousness, as opposed to perpetuating the stereotypes played by many other Black actors of their day. They defended Paul Robeson at a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing, spoke out against the Vietnam War alongside Martin Luther King, and Davis gave the eulogy at Malcolm X’s funeral. In his original review of Do the Right Thing, Vincent Canby wrote that the performers “seem to preside over it, as if ushering in a new era of black filmmaking.”

Lee’s dialectical intentions in both form and function are suffused with rich intertextuality that informs his casting and the direction of his actors, and it remarks on the history of race relations in America. Such choices appear in his casting of the Bed-Stuy elders, Da Mayor and Mother Sister, played by Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, the real-life couple whose activism and participation in the Civil Rights Movement goes back to the 1950s. In a 2018 profile in The New York Times, the couple was described as “stalwarts of the civil rights movement who navigated the sometimes contentious lines dividing different parts of the broader black freedom struggle.” Married in 1948, Davis and Dee starred in several Broadway productions together, including the original 1959 production of A Raisin in the Sun. Over the years, the couple continued to act together, but they also became voices in the sociopolitical discussions of the day as they made speeches, wrote articles, and performed in roles that advanced African American identity in the cultural consciousness, as opposed to perpetuating the stereotypes played by many other Black actors of their day. They defended Paul Robeson at a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing, spoke out against the Vietnam War alongside Martin Luther King, and Davis gave the eulogy at Malcolm X’s funeral. In his original review of Do the Right Thing, Vincent Canby wrote that the performers “seem to preside over it, as if ushering in a new era of black filmmaking.”

Lee’s interest in the theatrical legacy of actors extends from Davis and Dee to the Oscar-nominated turn by Danny Aiello, who developed and deepened his character into more than the racist figure Lee originally wrote. Davis and Dee’s performances in the film exist in another, older theatrical style, as their scenes play out in a stagey mini-drama with allusions to the past. In tender performances that could have been authored by playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the two characters have lived through the last half-century of racial tensions and personal failures, and the scars weigh on them. Though the details of their characters’ lives remain scant, the presence of these actors as these characters tells us everything we need to know about them. The performances themselves are theatrical and marked by emotional projection; their voices and expressions reach to the back row, while their presence offers a metatextual link to the tradition of progressive African American voices in cinema and theater. In a different sort of performance, Aiello and Turturro carry out their roles with a naturalism defined by the characters’ shared background, which the actors improvised on the set. In a scene of pronounced psychological realism, Sal and Pino discuss the pizzeria’s legacy, Sal’s devotion to the neighborhood, and Pino’s unwavering racism, and the scene transforms Sal into someone worthy of the audience’s empathy.

Lee grants humanity to each of his characters, while also demonstrating how quickly racism and anger strip away that humanity. In the climactic moment, Mookie, often a voice of reason, shouts “Hate!” before he tosses a garbage can into Sal’s window. During the riot, the seemingly goodhearted Smiley lights the match that sets Sal’s ablaze, while the sweet Mother Sister shouts “Burn it down!” outside. It is the film’s enduring dialectic between nonviolence and violence, love and hate, that keeps the viewer engaged in an essential and productive discussion. The end titles put much of Do the Right Thing into a constructive, open-ended context by questioning what constitutes the appropriate action for people of color to combat racism given the divergent lessons of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. Two quotes appear on the screen. First, King denounces violence as a method to bring about racial justice because it stops a healing dialogue and achieves only “a descending spiral ending in destruction for all.” Second, Malcolm X calls the use of violence in “self-defense” a form of “intelligence.” Before the end credits roll, a photograph of the two leaders laughing and shaking hands appears on the screen, the same photo Smiley hawks throughout the film. Lee ends his masterpiece by juxtaposing two personal philosophies that remain at the center of an ongoing debate.

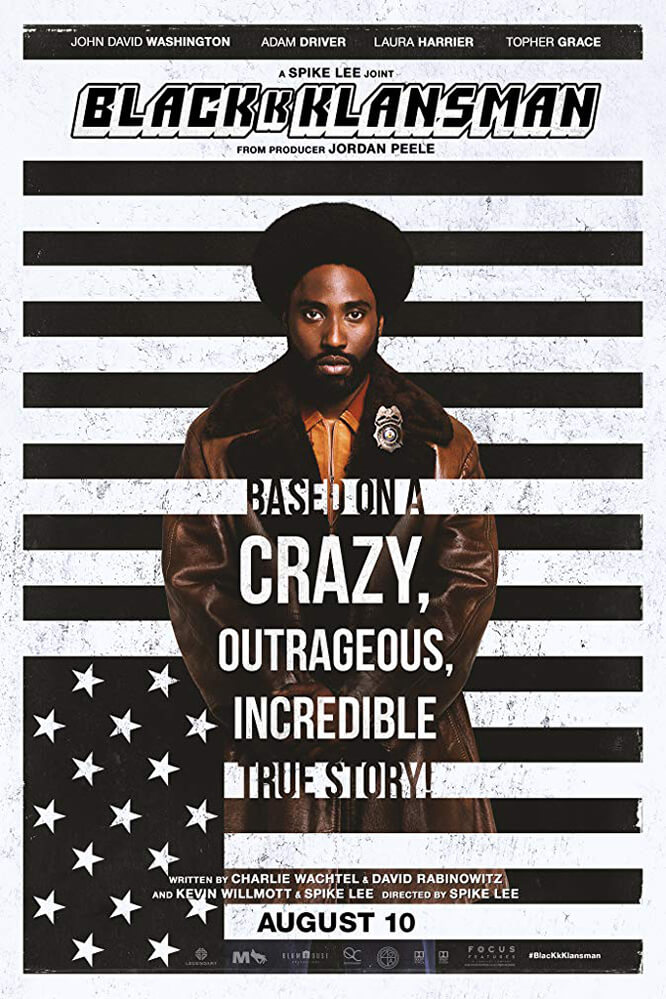

Do the Right Thing awakens and disrupts the viewer with its questions and the Brechtian methods with which they are asked, forcing us into self-exploration and, hopefully, some measure of understanding as we attempt to define what is the right thing and locate the power that must be fought. The Bed-Stuy neighborhood and its population serve as a living mural, a work of cinematic art whose theatricality and representational motivations provoke the viewer into investigation. It continues to be among the most socially relevant and even prescient films ever to reach American audiences, as discrimination, racial violence, police brutality, and racially tilted political power continues to define America. The film is an open wound, just as racism remains a break in the tissue of American identity, unable to heal due to the relentless aggravation that makes it every bit as relevant today as it was in 1989. Lee’s continued vitality as a filmmaker, later demonstrated in films from Malcolm X (1993) to BlackKklansman (2018), springs from his willingness to intervene in the limited discussion about race and ethnicity in American cinema. He continually challenges the conventional modes of discourse that exist today—which often attempt to provide the tidy, feel-good solutions of Hollywood catharsis—and instead confronts his audience with a parabolic wake-up call that broadcasts the complex history and persistent reality of American racial dynamics.

Do the Right Thing awakens and disrupts the viewer with its questions and the Brechtian methods with which they are asked, forcing us into self-exploration and, hopefully, some measure of understanding as we attempt to define what is the right thing and locate the power that must be fought. The Bed-Stuy neighborhood and its population serve as a living mural, a work of cinematic art whose theatricality and representational motivations provoke the viewer into investigation. It continues to be among the most socially relevant and even prescient films ever to reach American audiences, as discrimination, racial violence, police brutality, and racially tilted political power continues to define America. The film is an open wound, just as racism remains a break in the tissue of American identity, unable to heal due to the relentless aggravation that makes it every bit as relevant today as it was in 1989. Lee’s continued vitality as a filmmaker, later demonstrated in films from Malcolm X (1993) to BlackKklansman (2018), springs from his willingness to intervene in the limited discussion about race and ethnicity in American cinema. He continually challenges the conventional modes of discourse that exist today—which often attempt to provide the tidy, feel-good solutions of Hollywood catharsis—and instead confronts his audience with a parabolic wake-up call that broadcasts the complex history and persistent reality of American racial dynamics.

Bibliography:

Bogle, Donald. Hollywood Black: The Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers. Running Press, 2019.

Conrad, Mark T., editor. The Philosophy of Spike Lee. The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Enelow, Shonni. “Feel the Love.” Film Comment. July-August 2019, pp. https://www.filmcomment.com/article/feel-the-love. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Guerrero, Ed. Do the Right Thing. BFI Modern Classics. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

King, Susan. “‘Universal Was Not Afraid’: Spike Lee Reflects on the Fearmongering That First Met ‘Do the Right Thing’.” The Hollywood Reporter. 2019 June 28. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/do-right-thing-spike-lee-reflects-fearmongering-first-met-1989-film-1220715. Accessed 21 July 2019.

Lee, Spike, and Lisa Jones. Do the Right Thing: A Spike Lee Joint. Simon and Schuster, 1989.

Reid, Mark A., editor. Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Schuessler, Jennifer. “Portrait of a Marriage, Onstage and at the Barricades.” The New York Times. 12 November 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/12/arts/ossie-davis-ruby-dee-archives-schomburg.html. Accessed 20 July 2019.

Sterritt, David. Spike Lee’s America. Polity Press, 2013.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review