The Definitives

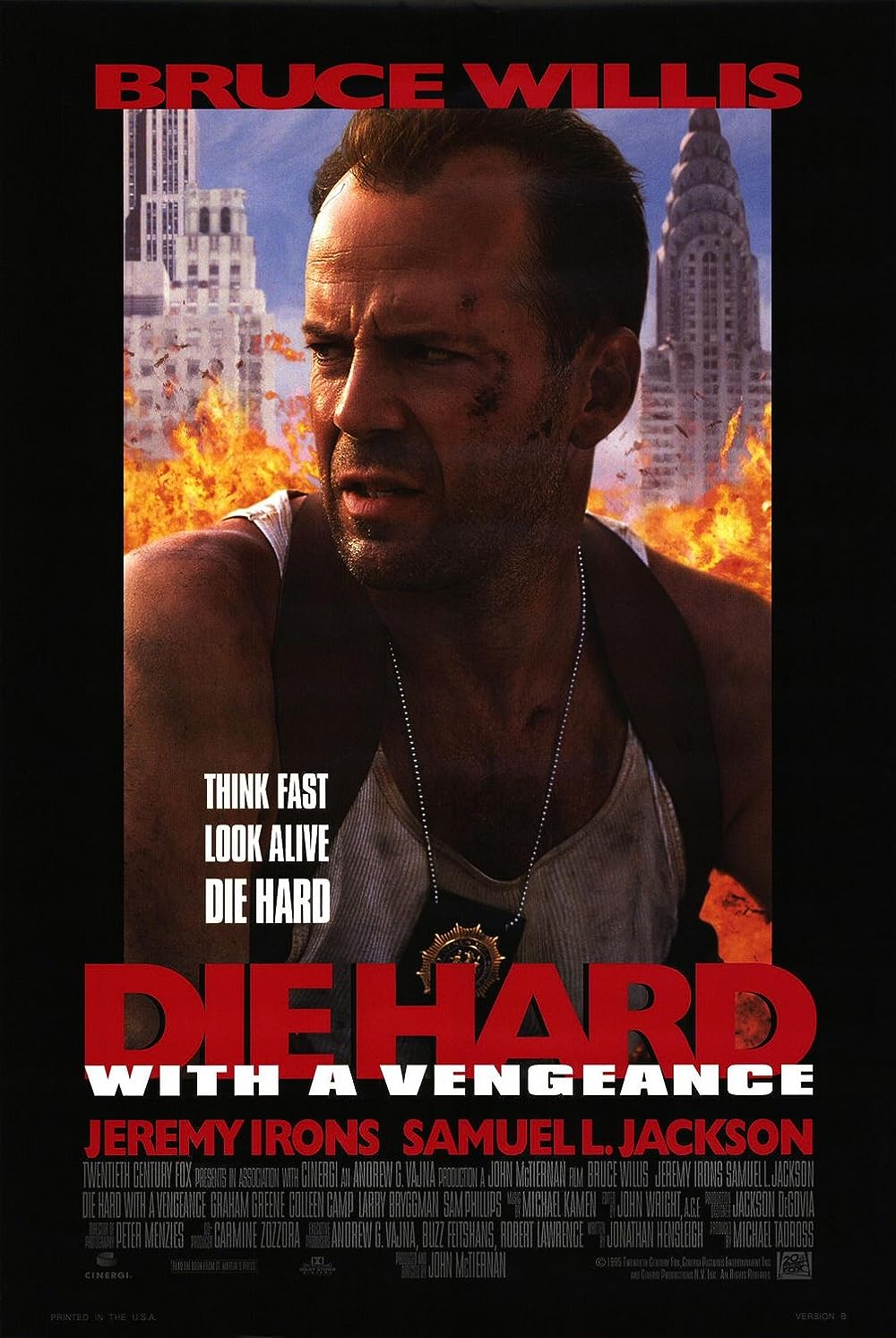

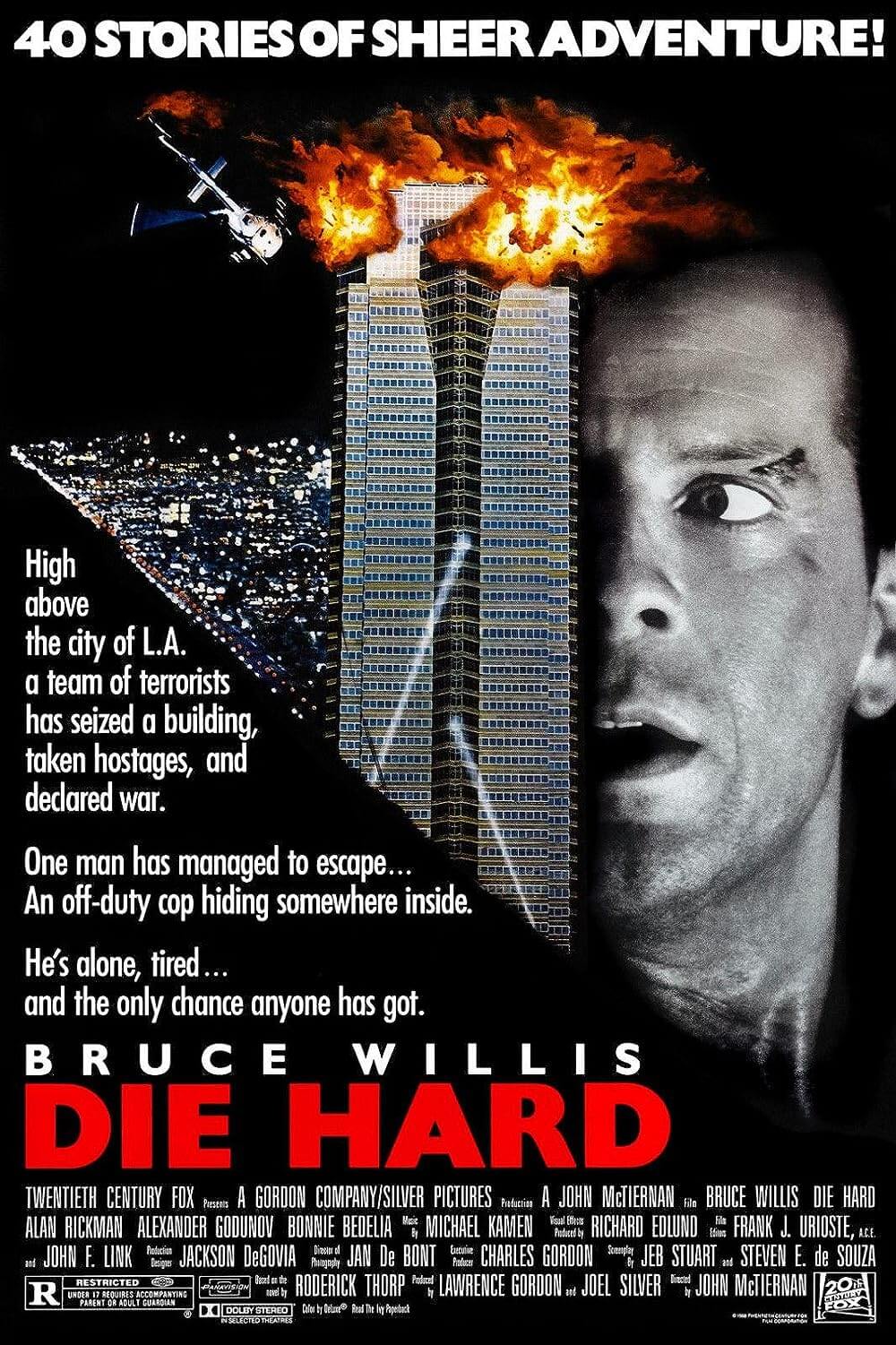

Die Hard (1988)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

An alternative to homogenized Hollywood action films, Die Hard incorporates qualities otherwise absent from action heroes prior to the film’s release: Personal shortcomings, vulnerability, and fallibility. In a word, humanity. These are the components that make Bruce Willis’ John McClane the screen’s most affable and relatable action hero, and what have bonded audiences to him for over twenty-five years. Considered through a series of trials seemingly designed to test and therein reaffirm his pointedly New Yorker masculinity, McClane represents a hero cop the likes of which moviegoers had never seen in 1988, just as the film itself was so unique and brightly innovative within its genre. Released by Twentieth Century Fox to thundering success, the film launched the career of star Willis into that of a screen icon, began an entertaining franchise that followed with multiple sequels, and spawned countless copycats trying to achieve the same thrilling claustrophobic magic of the original. But the first remains the gold standard for action filmmaking; what action movie tropes Die Hard doesn’t follow, it reinvents or altogether originates, and all of them have yet to be bettered.

Developed from Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza’s adaptation of Richard Thorp’s source novel, Nothing Lasts Forever, the film became another project on which producer Joel Silver and director John McTiernan, who made Predator together the year before, could collaborate. Their budget was a staggeringly low $30 million; if produced today, Die Hard would surely pass the hundred million dollar mark. Casting inexpensive actors kept costs down. Aside from Blind Date (1987) and his 5-year run on TV’s Moonlighting, Bruce Willis was a relative unknown chosen only after Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, and Richard Gere turned down the McClane role. Stage actor Alan Rickman, hired for his first motion picture by Silver, created the archetypal Euro-trash villain with Hans Gruber, and in the years to come would be hired for other villain roles in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1990) and Quigley Down Under (1991). Somehow, test screenings received poor feedback, which Fox believed due to Willis’ unproven status as an action star. Unfavorable testing meant Fox had all but written off Die Hard as a guaranteed flop. And though the film’s eventual $80 million box-office take also sounds paltry when compared to today’s popular franchises, it nearly tripled its budget and surprised everyone involved when it performed so well.

What makes Die Hard such a unique experience, when set apart even from its sequels, is the feeling that McClane is not an action hero—he’s just a normal guy in the wrong place at the wrong time. Outmatched and outgunned, he bitches about his bad luck and copes with his impossible situation through sarcasm. Long before McClane ever took a fire hose-assisted dive off Twentieth Century Fox headquarters (standing in for Nakatomi Plaza), action heroes like Schwarzenegger, Stallone, and the various James Bonds were performing similar stunts in popcorn-munching shoot-em-ups and withstanding infinite blows with nary a scratch. McClane is not an impervious robotic warrior carved from the template of the action movie gods. Embodied by Willis with pitch-perfect humanism, McClane bleeds, cries out in pain and emotional desperation, and has imperfections that become his trademark. One of the film’s most memorable characteristics is how much physical punishment McClane endures and how such wear amasses on him through the course of the film. His physical and psychological vulnerability and deep-seated flaws are what make him believable, enduring, and what ensure the viewer’s immersion. McClane, in his first of many man-alone-against-terrorist-group scenarios, may seem formulaic today, but only because Die Hard originated the formula.

What makes Die Hard such a unique experience, when set apart even from its sequels, is the feeling that McClane is not an action hero—he’s just a normal guy in the wrong place at the wrong time. Outmatched and outgunned, he bitches about his bad luck and copes with his impossible situation through sarcasm. Long before McClane ever took a fire hose-assisted dive off Twentieth Century Fox headquarters (standing in for Nakatomi Plaza), action heroes like Schwarzenegger, Stallone, and the various James Bonds were performing similar stunts in popcorn-munching shoot-em-ups and withstanding infinite blows with nary a scratch. McClane is not an impervious robotic warrior carved from the template of the action movie gods. Embodied by Willis with pitch-perfect humanism, McClane bleeds, cries out in pain and emotional desperation, and has imperfections that become his trademark. One of the film’s most memorable characteristics is how much physical punishment McClane endures and how such wear amasses on him through the course of the film. His physical and psychological vulnerability and deep-seated flaws are what make him believable, enduring, and what ensure the viewer’s immersion. McClane, in his first of many man-alone-against-terrorist-group scenarios, may seem formulaic today, but only because Die Hard originated the formula.

A New York cop, McClane visits his estranged wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia) for Christmas in Los Angeles, and a group of international terrorists, headed by Rickman’s refined Hans Gruber, take over her workplace in Nakatomi Plaza. In hiding and taking out the terrorists one by one, McClane’s conflict proves unlike most battles in the action genre, in that he’s not just fighting the terrorists—he’s reclaiming his male authority over Holly. Subverting terrorists is simply a means to that end. When John arrives at Nakatomi, he finds Holly has done well for herself in an executive role under her maiden name, Gennero, and for her hard work, she’s earned a Rolex prize, a symbol of her success as a modern woman who has no apparent need for a husband. Holly and John’s respective West Coast/ East Coast living arrangements, John’s threatened male ego over Holly’s use of her maiden name Gennero, and Holly’s Rolex-rewarded success at Nakatomi—these are the most immediate conflicts for McClane to resolve. Mere terrorist threats provide McClane the opportunity to place himself in control (albeit indirectly); fortunately, Holly is in a position that she needs to be rescued, and therein she needs her estranged husband to survive.

Innately heroic, sympathetic, and heterosexual, John McClane contains qualities that go hand-in-hand with his status as a New Yorker. After all, the stereotypical New York persona of 1988 could be personified by a tough heterosexual male. Indeed, Die Hard would not be Die Hard if McClane hailed from Delaware. McClane confirms his heterosexual status early on, both in sexual and modernized cowboy terms. He displays hetero characteristics not by his association with Holly, but rather through his wandering eyes that scope-out women on the plane and in the airport, his aversion to a male kiss at the Nakatomi Christmas party, and every time he revisits a naked pin-up girl cutout posted on a maintenance wall in Nakatomi Plaza. When first arriving in Los Angeles, McClane finds himself virginal to West Coast ways. “Only in L.A.” becomes his motto, as if L.A. is silly, off somehow, and perhaps effeminate or homosexual, whereas New York is effectually masculine and heterosexual. McClane is a tough New York cop; whereas one Los Angeles SWAT team member shouts “Ow!” after he bumps into a rose bush thorn. Consequently, McClane is established as a newly envisioned but classical Western hero—an Easterner “goin’ out West” to tame the frontier. Gruber, McClane’s nemesis throughout the film via walkie-talkie, even points this out later by referring to McClane as a cowboy.

Innately heroic, sympathetic, and heterosexual, John McClane contains qualities that go hand-in-hand with his status as a New Yorker. After all, the stereotypical New York persona of 1988 could be personified by a tough heterosexual male. Indeed, Die Hard would not be Die Hard if McClane hailed from Delaware. McClane confirms his heterosexual status early on, both in sexual and modernized cowboy terms. He displays hetero characteristics not by his association with Holly, but rather through his wandering eyes that scope-out women on the plane and in the airport, his aversion to a male kiss at the Nakatomi Christmas party, and every time he revisits a naked pin-up girl cutout posted on a maintenance wall in Nakatomi Plaza. When first arriving in Los Angeles, McClane finds himself virginal to West Coast ways. “Only in L.A.” becomes his motto, as if L.A. is silly, off somehow, and perhaps effeminate or homosexual, whereas New York is effectually masculine and heterosexual. McClane is a tough New York cop; whereas one Los Angeles SWAT team member shouts “Ow!” after he bumps into a rose bush thorn. Consequently, McClane is established as a newly envisioned but classical Western hero—an Easterner “goin’ out West” to tame the frontier. Gruber, McClane’s nemesis throughout the film via walkie-talkie, even points this out later by referring to McClane as a cowboy.

McClane’s masculinity and human susceptibility are further defined by his body. When the terrorists break in, McClane has been washing up after a long flight wearing nothing but a white undershirt, slacks, and bare feet—his garb for the film’s duration. Not protected by bullet-proof vests or Robocop armor, McClane is, for all intents and purposes, stripped down. In this raw form, he overpowers foreign enemies without benefit of protection, as though his most simplified nature and manhood are enough to mow down terrorist threats. And yet, when not armored to the teeth, action heroes are often rippling and shirtless, another heroic stereotype McClane avoids. From the naked appearance of future cyborgs who have traveled into back in time in The Terminator movies, to John Rambo’s sweaty shirtlessness, male action heroes often necessitate their own visually remarkable musculature, proving their exceptional masculinity to the viewer by way of their biceps and pectorals. Willis does not reduce his character to a faceless, muscle-bound body, however; his body is not the typically ripped male action hero physique. He has strength and dexterity to be sure; he’s lean but lacks the veiny, sinewy, herculean body of a Schwarzenegger or Stallone.

Already an underdog compared to other action heroes, McClane’s unassuming physique and barefoot state leave him much to overcome, as does the femininity that this state implies. In the first scenes, a fellow airplane passenger suggests McClane “make fists” with his toes to relieve jet lag. McClane offers a look of skepticism, perhaps because of the ridiculous or feminine nature of the act. Toes or feet are often a metonym for femininity (rarely are there women with foot fetishes in film); nonetheless, minutes later, McClane is barefoot in Holly’s office curling his toes. Clenching them into fists acknowledges that McClane resists stereotypical, absolutist tough-guy ideals—that his feminine side is indulged in this private act (one he would certainly not perform in front of Holly or Gruber)—and also twists that femininity into something symbolically male: fists. McClane’s male and female egos seem to be at war. While he can curl his toes to relieve jetlag, he still must rescue his wife and solidify his status as the dominant male in their relationship. Secretive admittances of femininity aside, in contrast, McClane’s entire ascension to the top of Nakatomi Plaza signifies an unprecedented phallic growth, complete with an “explosive climax”. Rather than accepting capture by Gruber’s threatening male presence, McClane escapes, preventing symbolic castration. Proving his undeniably brash and predominant masculinity, he climbs a suggestively shaped building, killing terrorist after terrorist along the way, all the while usurping Gruber’s threat to McClane’s manhood—the next best thing to a pissing contest. And what better way to illustrate McClane’s superior New York masculinity over L.A.’s dainty, comparatively feminine persona, than coming all over it?

Already an underdog compared to other action heroes, McClane’s unassuming physique and barefoot state leave him much to overcome, as does the femininity that this state implies. In the first scenes, a fellow airplane passenger suggests McClane “make fists” with his toes to relieve jet lag. McClane offers a look of skepticism, perhaps because of the ridiculous or feminine nature of the act. Toes or feet are often a metonym for femininity (rarely are there women with foot fetishes in film); nonetheless, minutes later, McClane is barefoot in Holly’s office curling his toes. Clenching them into fists acknowledges that McClane resists stereotypical, absolutist tough-guy ideals—that his feminine side is indulged in this private act (one he would certainly not perform in front of Holly or Gruber)—and also twists that femininity into something symbolically male: fists. McClane’s male and female egos seem to be at war. While he can curl his toes to relieve jetlag, he still must rescue his wife and solidify his status as the dominant male in their relationship. Secretive admittances of femininity aside, in contrast, McClane’s entire ascension to the top of Nakatomi Plaza signifies an unprecedented phallic growth, complete with an “explosive climax”. Rather than accepting capture by Gruber’s threatening male presence, McClane escapes, preventing symbolic castration. Proving his undeniably brash and predominant masculinity, he climbs a suggestively shaped building, killing terrorist after terrorist along the way, all the while usurping Gruber’s threat to McClane’s manhood—the next best thing to a pissing contest. And what better way to illustrate McClane’s superior New York masculinity over L.A.’s dainty, comparatively feminine persona, than coming all over it?

Male dominance and substantiation become Die Hard’s underlying theme and central conflict, whereas the basic “saving the day” plot feels secondary. McClane resolves said conflict by reaching a C4-induced orgasm, rescuing his damsel-in-distress, and reestablishing solidity in his otherwise broken marriage to Holly. The building itself, a glass tower, describes the fragility of masculinity—just how threatening a challenge is for the male ego. And what challenges there are: Gruber, aggressive SWAT teams, FBI assault choppers, and LAPD armed carriers. At any moment McClane could shatter, but with broken glass all around him, he walks right over it, barefoot and bleeding. Though his bare feet might suggest vulnerability or femininity in another hero, McClane owns this state by sprinting across the glass while dodging bullets. His feet gush blood in an obviously painful moment, but McClane, talking to his compatriot Sgt. Powell (Reginald VelJohnson) on a walkie-talkie, remains calm and collected in voice. Those of us in the audience see his face, wincing in pain. McClane even becomes a shoulder to cry on as Powell confesses he accidentally shot a child on the job, allowing for a moment of male bonding that unfurls feminine qualities in both. McClane is at his weakest when pulling the glass from his foot, eventually weeping as he communicates to Powell his goodbye message and apology to Holly, a message she never hears because McClane survives; had she heard such a tearful confession, doubtless McClane’s male ego could not have been restored. By the end of the film, both officers’ problems are solved and male egos intact: Powell guns down the last surviving terrorist to redeem himself and McClane reclaims Holly.

Also necessary is McClane’s need to squash out his competition. In his plot to invade Nakatomi Plaza under the guise of international terrorists, Gruber’s master plan, quite cleverly, is an elaborate heist that leaves Holly’s male coworkers, McClane’s initial competition, dead when they interfere. As Gruber has seized control of the glass phallus, McClane’s eventual orgasmic and explosive victory also signals Gruber’s masculine failure. Throughout the film, Gruber attempts to gain control of the building, asserting his power over this massive phallic symbol, and thus declare his own masculine identity. Each time one of Gruber’s terrorists is pumped full of lead or an entire floor is detonated, Gruber loses men, thus control over the phallic glass tower. McClane, a self-proclaimed “fly in the ointment”, eventually stomps-out Gruber’s masculinity atop Nakatomi Plaza, thwarting the final plan in a shower of flames and raining-down office paper. McClane even goes so far as to drop Gruber out a window by unfastening Holly’s Rolex, and in this action solves two problems at once: he kills the bad guy, but he also unfastens Holly from her symbol of success, feminine independence, and occupational authority over her husband.

Also necessary is McClane’s need to squash out his competition. In his plot to invade Nakatomi Plaza under the guise of international terrorists, Gruber’s master plan, quite cleverly, is an elaborate heist that leaves Holly’s male coworkers, McClane’s initial competition, dead when they interfere. As Gruber has seized control of the glass phallus, McClane’s eventual orgasmic and explosive victory also signals Gruber’s masculine failure. Throughout the film, Gruber attempts to gain control of the building, asserting his power over this massive phallic symbol, and thus declare his own masculine identity. Each time one of Gruber’s terrorists is pumped full of lead or an entire floor is detonated, Gruber loses men, thus control over the phallic glass tower. McClane, a self-proclaimed “fly in the ointment”, eventually stomps-out Gruber’s masculinity atop Nakatomi Plaza, thwarting the final plan in a shower of flames and raining-down office paper. McClane even goes so far as to drop Gruber out a window by unfastening Holly’s Rolex, and in this action solves two problems at once: he kills the bad guy, but he also unfastens Holly from her symbol of success, feminine independence, and occupational authority over her husband.

For all the Freudian interpretation this film provides, it also provides a nationalistic interpretation as well. American exceptionalism, closely related to male exceptionalism in film, rears its head as the dialogue between McClane and Gruber sets Die Hard up as a modern-day Western in which McClane is the good American cowboy and Gruber is a villainous foreign invader (perhaps even a Native American). After making a High Noon reference, Gruber is proved un-American and thus criminal almost exclusively through his knowledge of Hollywood movie trivia. Gruber, a German-born Brit, claims John Wayne starred in High Noon, and McClane, the American, corrects him to the fact that it was Gary Cooper. By association, this underlines several Good Guy vs. Bad Guy scenarios from Westerns, using High Noon’s classic standoff between Marshall Will Kane and criminal Frank Miller as a model. It suggests the cowboy McClane and criminal Gruber engage in a uniformly classic struggle of pure good vs. pure evil, thus idealizing their conflict as something “classic” in the viewer’s eyes. Given High Noon’s intended allegory to McCarthyism, we see their duel illustrated in terms of McClane’s American purity vs. Gruber’s pro-communist (in metaphor only) un-American impurity.

In fact, the film’s most memorable line comes as an embrace of traditional Western heroes, using McClane’s own ironic humor as a postmodern shift for traditional cowboy war-cries like yippee-ki-yay. In Die Hard’s sequels the line is used as a garnish; only in its original use did it have any meaning:

Gruber: You know my name but who are you? Just another American who saw too many movies as a child? Another orphan of a bankrupt culture who thinks he’s John Wayne? Rambo? Marshall Dillon?

McClane: Was always kinda partial to Roy Rogers actually. I really dig those sequined shirts.

Gruber: Do you really think you have a chance against us, Mister Cowboy?

McClane: Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker.

In this most famous of movie lines we see how, whether running barefoot across broken glass or just barely catching an opening as he falls down a ventilation shaft, McClane does the impossible, and yet makes it all very plausible not only through his vulnerable male ego, but his wisecracks throughout the situation. McClane’s dialogue is filled with witty comebacks, one-liners, and pop-culture references lost on Gruber. Not that Gruber is always there to hear them. “Now I know what a TV dinner feels like,” he quips to himself as he squeezes through a vent. Some of McClane’s best moments are by himself as he talks himself through the situation. Whereas stone-faced lone heroes had machine-gunned their way through countless bad guys in action movies before, McClane just an average cop, after all, not even a super-cop. When the terrorists first arrive, his first instinct is to escape and call for help. “Why the fuck didn’t you stop them, John?” he asks himself after first running. “Because then you’d be dead, too, asshole,” he answers. In this unpolished treatment of McClane, and the character’s ability to make observations about his own situation, he becomes instantly “real” when compared to his unstoppable counterparts. He’s also completely sympathetic as an underdog fighting a much larger opponent while contending with the bureaucratic nonsense of local authorities: Deputy Police Chief Dwayne T. Robinson (Paul Gleeson) and FBI Agents Johnson and Johnson (Robert Davi and Grant L. Bush). Male action heroes are now typically flawed, sarcastic, unhappy individuals, made heroic through whatever conflict they face. They get shot, dislocate shoulders, have mental disorders, drink too much, and on rare occasion even sacrifice themselves. McClane started it all.

In this most famous of movie lines we see how, whether running barefoot across broken glass or just barely catching an opening as he falls down a ventilation shaft, McClane does the impossible, and yet makes it all very plausible not only through his vulnerable male ego, but his wisecracks throughout the situation. McClane’s dialogue is filled with witty comebacks, one-liners, and pop-culture references lost on Gruber. Not that Gruber is always there to hear them. “Now I know what a TV dinner feels like,” he quips to himself as he squeezes through a vent. Some of McClane’s best moments are by himself as he talks himself through the situation. Whereas stone-faced lone heroes had machine-gunned their way through countless bad guys in action movies before, McClane just an average cop, after all, not even a super-cop. When the terrorists first arrive, his first instinct is to escape and call for help. “Why the fuck didn’t you stop them, John?” he asks himself after first running. “Because then you’d be dead, too, asshole,” he answers. In this unpolished treatment of McClane, and the character’s ability to make observations about his own situation, he becomes instantly “real” when compared to his unstoppable counterparts. He’s also completely sympathetic as an underdog fighting a much larger opponent while contending with the bureaucratic nonsense of local authorities: Deputy Police Chief Dwayne T. Robinson (Paul Gleeson) and FBI Agents Johnson and Johnson (Robert Davi and Grant L. Bush). Male action heroes are now typically flawed, sarcastic, unhappy individuals, made heroic through whatever conflict they face. They get shot, dislocate shoulders, have mental disorders, drink too much, and on rare occasion even sacrifice themselves. McClane started it all.

In succeeding years, actioners from Under Siege (1992) to Dredd (2012) pilfered from Die Hard’s harmony of claustrophobic space and big action thrills. These copycats are often described as “Die Hard-on-a…” (bus, plane, boat, train, etc.) to acknowledge their obvious derivation. This is not only because of the film’s box-office success or sheer, breathless entertainment value, but because director McTiernan made a wonderfully crafted picture teeming with visual and subtextual purpose as outlined above. Beyond the wellspring of symbolism throughout the film, cinematographer Jan De Bont (who in 1994 directed his own Die Hard-on-a-bus riff, Speed) incorporates countless visual flourishes to keep every frame interesting: he projects light through blinds, grills, and grates; he uses steam and lens flares to fill the frame; he bounces light off of water for a glittering reflective effect. Editors John F. Link and Frank J. Urioste piece together De Bont’s slick lensing to make every action scene clear, even gorgeous, especially when compared to today’s shaky standards. Production designer Jackson De Govia created the whole skyscraper setting by using an actual in-construction building and augmenting it with touches of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Japanese-inspired architecture. Overall, McTiernan’s production is an accomplished piece of filmmaking whose influence in the genre is still evident.

As an aside, one would be remiss if Michael Kamen’s score went unnoticed. Along with the Christmastime setting, the composer plays a deepened orchestral version of “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Now considered a holiday favorite, “Ode to Joy” finds itself bonding directly to Gruber’s crew, whereas McClane has no significant riff of his own, aside from the occasional whistle of “Jingle Bells”. Primarily due to Kamen’s use of “Ode to Joy” and the inclusion of “Let it Snow” at the film’s finale, Die Hard, a violent, R-rated, family unfriendly blockbuster set in the snowless (unless you count falling paper in the finale) winter of Los Angeles, is now strangely a Christmas classic. Come this Holiday season, consider forgoing your annual dose of A Christmas Story or It’s a Wonderful Life for something less family oriented and more actionized. Nothing says “Happy Holidays” like McClane’s bloodied terrorist arriving by elevator with “Now I have a machine gun. Ho-ho-ho” stenciled in blood on his sweater.

As an aside, one would be remiss if Michael Kamen’s score went unnoticed. Along with the Christmastime setting, the composer plays a deepened orchestral version of “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Now considered a holiday favorite, “Ode to Joy” finds itself bonding directly to Gruber’s crew, whereas McClane has no significant riff of his own, aside from the occasional whistle of “Jingle Bells”. Primarily due to Kamen’s use of “Ode to Joy” and the inclusion of “Let it Snow” at the film’s finale, Die Hard, a violent, R-rated, family unfriendly blockbuster set in the snowless (unless you count falling paper in the finale) winter of Los Angeles, is now strangely a Christmas classic. Come this Holiday season, consider forgoing your annual dose of A Christmas Story or It’s a Wonderful Life for something less family oriented and more actionized. Nothing says “Happy Holidays” like McClane’s bloodied terrorist arriving by elevator with “Now I have a machine gun. Ho-ho-ho” stenciled in blood on his sweater.

Though Die Hard is less an escape into mindless action than one man’s desperate mission to reclaim his family and assert himself as paterfamilias, the film’s divergence from standard Hollywood actioner tropes is what makes the film great, timeless even. Justifying male power in every other scene, Die Hard subjects audiences to McClane’s hard-edged, unyielding attempts to boast his masculinity through his occasional feminine qualities. And granted, if reading the film from a feminist point of view, one might find the subtext questionable. Still, that there is a subtext involving a hero whose primary conflict is the dynamic between his masculine and feminine sides elevates the film from its brethren. McClane’s macho behavior is easily dismissed because, quite simply, the picture is just too damn fun, smart, barely dated, and undoubtedly readable beyond traditional action movies. Die Hard changed the genre forever. Its triumph resides in the complexity of John McClane. Put any other hero-type in his place and the film fails, or becomes banal and common. Rarely does an action blockbuster take such risks and offer a hero whose vulnerability and humanism outweighs the picture’s violence, even as it supplies expertly arranged action. That Die Hard achieves this unlikely equilibrium makes it perhaps the best film of its kind.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review