The Definitives

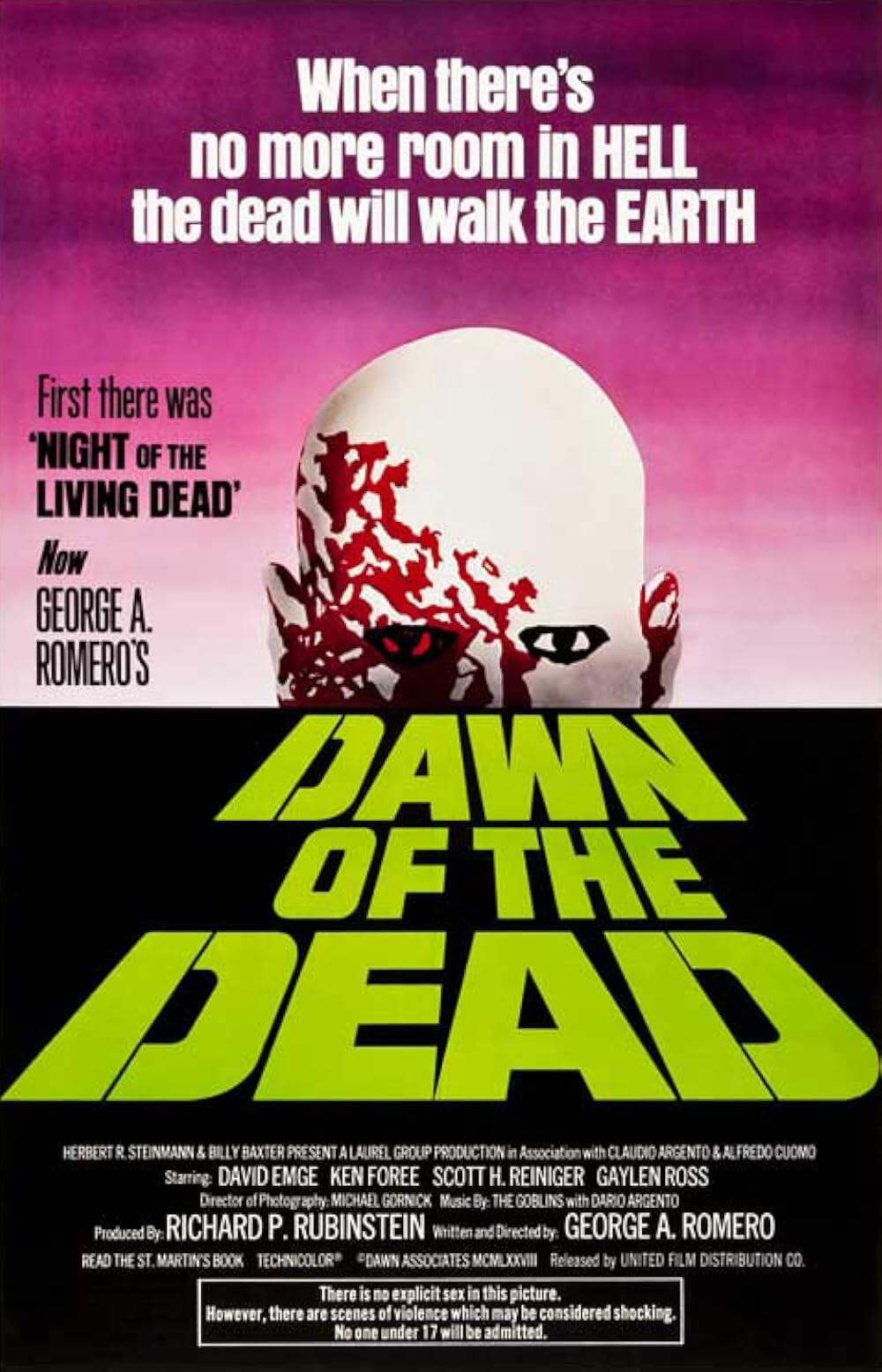

Dawn of the Dead (1978)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

I will knock down the Gates of the Netherworld,

I will smash the doorposts, and leave the doors flat down,

and will let the dead go up to eat the living!

And the dead will outnumber the living!

—Epic of Gilgamesh, written roughly 2500 BC

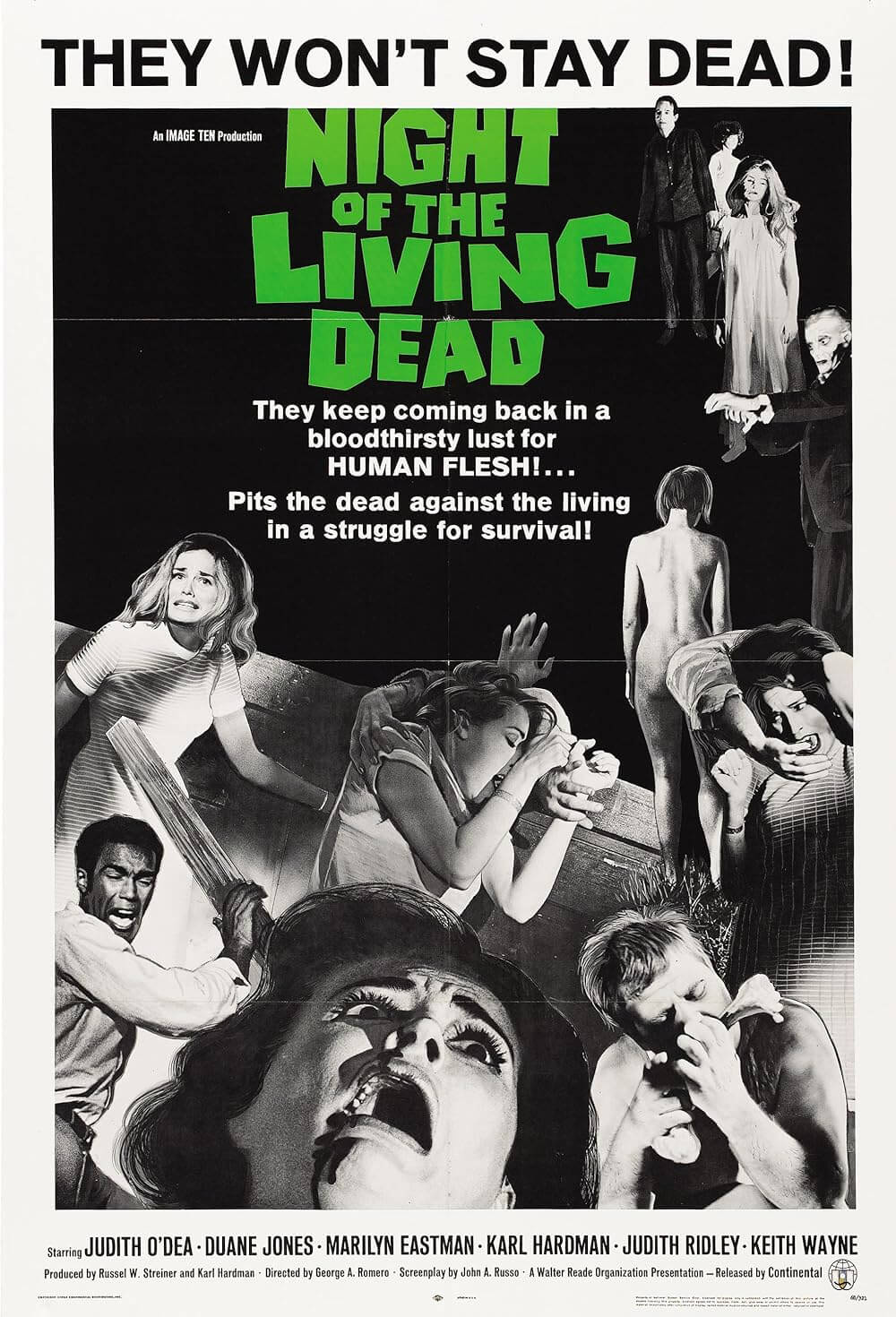

Every culture has its equivalent to a zombie, whether they are corporeal emblems of fear or representations of a broader social subject. Zombies exist as empty ciphers; authors and filmmakers use them to explore countless themes. Cinema often employs them as horror devices, as the faceless crowd of monsters. Their presence is fastened to a social commentary whose metaphor operates under the camouflage of blood and gore and violence. With his 1968 picture Night of the Living Dead, filmmaker George A. Romero introduced popular culture to what is now the iconic film and literary zombie. In the film, recently dead bodies reanimate into decaying, barely mobile corpses without logic or reason. Their sole purpose is to feed on the flesh of the living. Victims bitten by zombies turn into zombies themselves, adding to the numbers of living dead with each passing moment. The survivors hole-up in an empty farmhouse, fighting off panic and the oncoming horde of undead while witnessing the first stages of a zombie apocalypse. By the time of Romero’s first zombie sequel, Dawn of the Dead, bedlam has set his fictional world afire.

Released in 1978, Dawn of the Dead quickly establishes how zombie infection spreads in populated areas—and the term “infection” is used casually here, as Romero’s series avoids giving the exact cause of the outbreak (radiation from an exploded Venus satellite is suggested in Night of the Living Dead). Populated areas are awash with the undead. News broadcasts dominate the airways and showcase arguments between experts on how to manage the crisis. Civilization has all but crumbled. SWAT men Peter (Ken Foree) and Roger (Scott H. Reiniger) clear out a project prior to their flight, seeing first-hand how the plague spreads in urban areas and how humanity resorts to awful lows because of it. Aside from zombie carnage, they witness a racist cop blast away innocent civilians and religious blindness cause suffering. They finally settle on fleeing with traffic reporter-friend Stephen (David Emge) and his pregnant lover Francine (Gaylen Ross) in Stephen’s traffic helicopter. Flying across unpopulated areas, they observe the countryside wrought with the undead. And after barely surviving a stop for gas, they find a place to collect themselves: a massive structure, a shopping mall, offers a landing and safety. Their prolonged stay results in Romero’s graphic critique of humanity and American consumer culture more than the monstrosity of the living dead, since the one bred the other.

Monroeville Mall was one of the first megalopolis shopping centers of its time. Its stores contain food, clothing, tools, guns—everything average consumers could hope for. Zombies flock to it, though not for a meal. Peter determines, “They’re after the place. They don’t know why. They just remember. Remember that they want to be in here.” Straggling undead wander about like window shoppers strolling on a lazy weekday afternoon, not buying, just looking. Zombies remember their consumer drive, making them less anonymous creatures and still remotely human. Within this detail, Romero notes his first link between consumers and zombies: Humans have a need for material indulgence, approximating the zombies’ blind need to eat human flesh—vices neither party necessarily needs, they just want. Our heroes resolve to stay in the complex and transform its storage room into their simulated apartment. While exploring the mall, the men leave pregnant Fran alone and unarmed; they return just in time to save her from a wandering Hare Krishna zombie. Stephen consoles her: “You should see all the great stuff we got, Frannie,” he says. “All kinds of stuff. This place is terrific. It really is. It’s perfect. All kinds of things. We’ve really got it made here, Frannie.” In a post-apocalyptic world where money is obsolete, his materialism frightens her.

Monroeville Mall was one of the first megalopolis shopping centers of its time. Its stores contain food, clothing, tools, guns—everything average consumers could hope for. Zombies flock to it, though not for a meal. Peter determines, “They’re after the place. They don’t know why. They just remember. Remember that they want to be in here.” Straggling undead wander about like window shoppers strolling on a lazy weekday afternoon, not buying, just looking. Zombies remember their consumer drive, making them less anonymous creatures and still remotely human. Within this detail, Romero notes his first link between consumers and zombies: Humans have a need for material indulgence, approximating the zombies’ blind need to eat human flesh—vices neither party necessarily needs, they just want. Our heroes resolve to stay in the complex and transform its storage room into their simulated apartment. While exploring the mall, the men leave pregnant Fran alone and unarmed; they return just in time to save her from a wandering Hare Krishna zombie. Stephen consoles her: “You should see all the great stuff we got, Frannie,” he says. “All kinds of stuff. This place is terrific. It really is. It’s perfect. All kinds of things. We’ve really got it made here, Frannie.” In a post-apocalyptic world where money is obsolete, his materialism frightens her.

For Stephen and the other men, this mall is a mound of gold, something to defend or even die for. Fran alone realizes their potential mistake: “I’m afraid. You’re hypnotized by this place. All of you. It’s so bright and neatly wrapped, you don’t see that it’s a prison too.” A true survivalist, the only one in the group, she continues, “Stephen, let’s just take what we need and keep going.” Her vote is the minority, however. Stephen and the others resolve that everything they need is right there. All entrances are sealed; they’re protected by shatterproof glass. Our heroes drive semi-trucks in front of each mall entrance, creating crude blockades. But this risky excursion to shield themselves marks the group: Roger is bitten and survives, for the time being—long enough to move the trucks into place and protect their new home. Their undead-free safe haven is realized after they kill the few remaining zombies inside the secured mall. Every contingency is thought-out to prevent their demise. Their sparsely stocked helicopter sits on the mall’s roof for a quick escape. They cloak the hallway leading to their storage room by installing a makeshift wall over the opening. Their sanctuary is hidden, should anyone, living or otherwise, come looking. They’ve thought of everything.

After Roger is bitten, he slowly turns. The others are tortured with the sounds of his winding down, his dying gibberish. At one point, he howls victory for their mall conquest: “We whipped ‘em, and we got it all!” Even in impending death, Roger’s obsession with what the mall offers preoccupies his mind; it is the one thing he can cling to in an otherwise chaotic world now lacking any semblance of social order. Surely, materialism affects modern consumers in the same way. The knickknacks and endless collections held by everyday people can engulf them, become an obsession, and even provide stability when there is none. Later, all zombie threats are expelled from their mall, including Roger, whom Peter kills at the point of reanimation. A subsequent melancholy strikes the group. With nothing to do, boredom and malaise set in. Once an empty space with blank walls and no carpet, they deck their storage room out like a posh apartment, complete with furniture, appliances, spices, and every superfluous amenity conceivable. They direct their attention toward the offerings of the mall. Going out to collect their clothes, watches, hats, chocolate, guns, makeup, and groceries, they mope back to their hideaway like wandering shoppers. Romero’s correlation between consumer culture’s listlessness and the lifeless crawl of the living dead is unmistakable.

Indeed, consumerism remains Romero’s true villain in Dawn of the Dead, not zombies. He equates the shopper with an undead consumer of humanity, as shown in the third act. Our three remaining heroes face a human biker gang of raiders. Before the onslaught, the three take one last look at their mall, almost as if saying goodbye to a lover. We see them in fur coats and swank outfits provided by their haven. Back in reality and facing a human threat, they replace their glitz with their former occupational garb, and they arm themselves with guns and ammo. Played by a real-life motorcycle gang and shown riding their actual bikes, the invading marauders unintentionally liberate Peter, Stephen, and Fran from their material trap. Bikers smash open an entrance, allowing hundreds of zombies back into the mall. Here Romero juxtaposes his two metaphoric zombie types: the undead and the consumers frantically clawing at each other for the mall’s contents. The ensuing battle depicts consumer genocide, simultaneously symbolized in horrific detail by the undead zombies devouring human flesh.

Indeed, consumerism remains Romero’s true villain in Dawn of the Dead, not zombies. He equates the shopper with an undead consumer of humanity, as shown in the third act. Our three remaining heroes face a human biker gang of raiders. Before the onslaught, the three take one last look at their mall, almost as if saying goodbye to a lover. We see them in fur coats and swank outfits provided by their haven. Back in reality and facing a human threat, they replace their glitz with their former occupational garb, and they arm themselves with guns and ammo. Played by a real-life motorcycle gang and shown riding their actual bikes, the invading marauders unintentionally liberate Peter, Stephen, and Fran from their material trap. Bikers smash open an entrance, allowing hundreds of zombies back into the mall. Here Romero juxtaposes his two metaphoric zombie types: the undead and the consumers frantically clawing at each other for the mall’s contents. The ensuing battle depicts consumer genocide, simultaneously symbolized in horrific detail by the undead zombies devouring human flesh.

An ambitious-minded and visualized low-budget film, Dawn of the Dead’s zombie effects were created by Romero’s longtime friend and coworker, FX guru Tom Savini. Savini used a gaudy, cheap 3M blood formula, recalling the thickness and brightness of a melted red crayon. He also picked a type of gray make-up for the living dead’s skin tones, which on film appears bluish. Within Savini’s exaggeration of blood and gore are graphic images, inciting appropriate ooohs and aaahs and the occasional scream. But there are also extreme, unnatural, primary color qualities that accentuate Romero’s cartoonish intent and virtual lampooning of consumer culture—an unintentional colorant note according to Savini, who originally called his color choices mistakes. To be sure, Romero’s film is a comic book ordeal with maximum ironic effect. Certainly, his use of the term “zombie” refers to more than just living dead status. Our four heroes in Dawn of the Dead are philosophical and social zombies, or slaves to The System. It is a common allegory: workers in bureaucratic office buildings are divided into cubicles, face computers, all with identical office furniture, pens, staplers, and other office supplies—they are the actual living dead. Romero, a longtime radical, translates conformity and orthodoxy into a lack of existence, hence its metaphoric translation into zombism.

Romero wasn’t the first creative to explore the dead returning to life. Religions use living dead as symbols since the beginning of recorded time, often to elicit the threat of damnation. The living dead represent victims punished by way of life without life—life without consciousness or a heartbeat, existing solely to destroy other life. Allegorical and straightforward references to zombies appear throughout religious history. However, the term “zombie” originated in Kongo, Africa, and did not appear in the English language until the nineteenth century. In the previously noted Epic of Gilgamesh, one of civilization’s earliest known written stories dating from the Sumerian empire, Ishtar threatens her father with “the living dead” that will “outnumber” and “eat the living.” Ancient Japanese Buddhists believed in Jikininki, cursed ghosts that devour corpses of the recently dead; however, Jikininki are inimitably self-aware and despise their undead hunger. Even pop-culture references such as Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein or early cinema like the 1932 Bela Lugosi shocker White Zombie suggest such symbolic themes.

The Christian Bible contains comparable references, with descriptions that recall plague-like, Romeroesque zombies. In the book of Zechariah, written roughly around 400 BCE, the prophet describes Judgment Day, beginning with changes in the world’s geography and landscape. He speaks of the Lord’s Plague that will be given to those who would harm Jerusalem. Zechariah writes in Chapter 14: 12-15: “Their flesh shall rot while they are still on their feet; their eyes shall rot in their sockets, and their tongues shall rot in their mouths. On that day a great panic from the Lord shall fall on them, so that each will seize the hand of a neighbor, and the hand of the one will be raised against the hand of the other.” With descriptions of decomposing flesh and “great panic,” Zechariah’s words bear a frightening resemblance to Romero’s zombie apocalypse mythology. Catholicism’s influences are blatant throughout the director’s work. “Seize the hand of your neighbor” could stand in for zombism spreading via bites, continuing from one person to the next like a disease. Talk of the apocalypse will invariably inspire the human association between the prophesied end of the world and the living dead, a venerable link thanks to religious fanaticism. Romero plays with religion throughout each of his zombie films, and ironically, his survivors often determine that God does not exist.

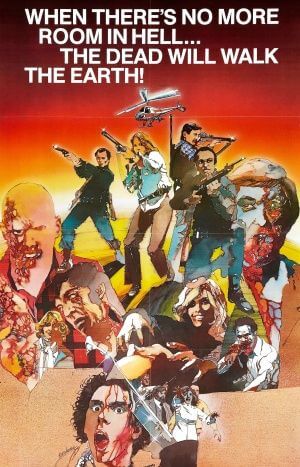

Peter’s famous quote (also Dawn of the Dead’s tagline) comes from his Voodoo priest father: “When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.” Religious beliefs in the living dead have some basis in fact, thanks to Voodoo myth. While sifting through pop-culture misconceptions about Voodoo practices and studied spiritual and remedial characteristics, one cannot ignore reports by Wade Davis. A noted author and Harvard ethnobotanist, Davis’ explorations into Haitian Voodoo pharmacology uncovered what appeared to be zombification. Haitian myth speaks of dead subjects awoken by a bokor or Voodoo priest, who controls his subject by possession or suggestion. Davis witnessed such zombification firsthand, later finding pharmacological reasoning behind it, however mysterious—with the use of a tetrodotoxin (a potent venom found in pufferfish), victims enter a near-death state. This effect can be prolonged for days, leaving vital signs barely visible even to doctors. Davis claimed another drug, usually a psychoactive ingredient, left the subject open to suggestion or possession. The resultant effect leaves the subject appearing active but also perceptibly dead.

Cinematic zombies habitually find themselves the substance of religious or sociological metaphor. Perhaps it is their anonymous, inhuman-but-human nature that makes them perfect vessels for symbolic meaning, though seldom satirically so like in Romero’s Dawn of the Dead. For example, Night of the Living Dead uses zombies to discuss racial violence vis-à-vis criticisms of American staples like media, government, and militia. In that film, panicky reporters give confusing accounts under the chaotic strain; government officials do not help identify the outbreak; even Romero’s saviors, the neighboring yokel militia, mistake the film’s Black hero (Duane Jones) for one of the living dead and kill him. Critics at the time saw the picture as an allegory to the Vietnam conflict or American racism. Although, it’s not hard to conceive that Romero challenges all establishments in Night of the Living Dead, suggesting the rather easy breakdown of humanity given the right situation. Most scholarly critiques of Night of the Living Dead argue a single, precise theme, but Romero looks at the all-encompassing picture within that film. His subsequent zombie movies center on more focused arguments developed from this model.

Romero calls his follow up to Dawn of the Dead, entitled Day of the Dead (1985), his favorite of his own pictures. The story takes place long after the zombie apocalypse has overrun the world. Scientists and military personnel in an underground compound search for a solution to the living dead problem. With little research progress to raise hopes, the compound’s few remaining survivors break down. Military men become power-hungry and anxious, even frenzied. The scientists have no prospects for a speedy solution. The chief scientific mind, Dr. Logan (Richard Liberty), experiments with a zombie he names “Bub” (Sherman Howard), hoping to domesticate it. He talks to it, even feeds it human flesh for a pseudo-Pavlovian response. Bub is certainly made more human as the mad Dr. Logan desires; instead of eating people, Bub prefers to shoot them with a gun. Meanwhile, Terry Alexander and Jarlath Conroy play the two civilians smart enough to keep away from any “organization,” knowing it will eventually collapse. With Day of the Dead, Romero attacks the inefficiency and sometimes lunacy of military, government, and scientific establishments, showing us the result when government haphazardly attempts to gain control of something irrepressibly chaotic.

Romero calls his follow up to Dawn of the Dead, entitled Day of the Dead (1985), his favorite of his own pictures. The story takes place long after the zombie apocalypse has overrun the world. Scientists and military personnel in an underground compound search for a solution to the living dead problem. With little research progress to raise hopes, the compound’s few remaining survivors break down. Military men become power-hungry and anxious, even frenzied. The scientists have no prospects for a speedy solution. The chief scientific mind, Dr. Logan (Richard Liberty), experiments with a zombie he names “Bub” (Sherman Howard), hoping to domesticate it. He talks to it, even feeds it human flesh for a pseudo-Pavlovian response. Bub is certainly made more human as the mad Dr. Logan desires; instead of eating people, Bub prefers to shoot them with a gun. Meanwhile, Terry Alexander and Jarlath Conroy play the two civilians smart enough to keep away from any “organization,” knowing it will eventually collapse. With Day of the Dead, Romero attacks the inefficiency and sometimes lunacy of military, government, and scientific establishments, showing us the result when government haphazardly attempts to gain control of something irrepressibly chaotic.

Romero’s 2005 picture Land of the Dead proposes that Americans fear their government when really we should be the corrupt government’s worst enemy. Survivors of the zombie apocalypse live on a sectioned-off part of Pittsburgh, a massive enclave surrounded by protecting water and electrified fences—a myth-named paradise they call Fiddler’s Green. The poor are extremely poor, while the rich are provided for in an executive building maintained by people of class and distinction. There is a vital parallel to George W. Bush, here represented by Paul Kaufman (Dennis Hopper), a money-grubbing, nose-picking executive, placed high up in his tower, uncaring for the population below. Meanwhile, zombies evolve and learn to think for themselves. Their Bub-like leader is Big Daddy (Eugene Clark), a zombie who slowly develops problem-solving skills, including the realization that water cannot drown the living dead (so much for escaping to a zombie-free island). The zombies’ small intellectual growth hints that the working classes have become philosophical zombies but can easily awake and overrun their oppressors.

In 2004, director Zack Snyder helmed Universal Studios’ remake of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, but it limits the desirable commentary on consumer culture. Screenwriter James Gunn offers a higher number of characters in the mall, meaning added deaths and a more linear storyline, although less satirical. Also absent is the biker gang, which takes away yet another layer of Romero’s thesis on humanity destroying itself. The jokes are more apparent with muzak humming Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” and characters exchanging typical horror-movie banter. Paper-thin characterizations notwithstanding, this group survival story succeeds with shocks and awes of expertly produced zombie gore and smartly imagined action-horror sequences, including a cringe-inducing zombie-baby delivery. The result of Snyder’s flashy, slow-motion heavy direction and the addition of running undead (derived from 2002’s 28 Days Later) makes for bloody, rousing entertainment, constructed skillfully, with merely the setting of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead repeated.

Examining Snyder’s remake, we realize what a thoughtful, anti-commercial film Romero made with his original. And he did it with just five-hundred thousand dollars, a low-budget enterprise given Romero’s massive scope. His script was over 200 pages, not because he intended to make a three-hour-plus horror movie, but because his descriptions are so exhaustive. Each sequence was illustrated with words long before shooting, so how unexpected it is that Romero’s preplanning is not followed with noticeably fluid camerawork or organization. Scenes such as Dawn of the Dead’s semi-truck moving were shot almost verbatim to the script, whereas the biker gang’s entrance and their entire pillage were improvised—Romero even randomly suggested the film’s comical pie fight. All at once, bikers laugh like circus clowns, attacking zombies with cream pies and seltzer sprays. Romero’s absurdist pie fight sequence underscores the entire film’s caustic, comic temperament, complete with muzak blaring throughout. Romero works happily within budgetary confines, allowing for strict discipline in some areas and readiness for improvisation in others. His fast, economic editing creates the film’s flow and suspense, and it’s never dependent on one angle or shot. His craftsmanlike brilliance resides within his ability to bring his own sometimes sporadic shots masterfully together in the editing room.

Political and social satire rarely gets as dark as George A. Romero’s films, where gags are outlined by living death and punctuated by sinewy, bloody gore. This implanted wink from the director reminds us that we should be both amused and shocked, as well as pondering his thoughtful underlying message. Romero’s pervasive, colorful violence in Dawn of the Dead denotes his focused statement against consumer culture. His archetypal, varying allegorical definitions for the zombie have lasted throughout his career, inspiring an entire subgenre of horror, with Dawn of the Dead as its unsurpassable masterpiece of complex characters and narrative symbolism. Where else are zombies mere background noise to what ostensibly becomes a drama about people who have given up on fighting for meaning in their lives? These are ambitious ideas for any film but especially in the horror genre, where the commercial demands for blood have a tendency to distract from the intended theme. Dawn of the Dead remains a landmark that elevates both its author and the genre.

Bibliography:

Gagne, Paul. The Zombies that Ate Pittsburgh. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1987.

Russell, Jamie. Book of the Dead. Surrey: FAB Press, 2005.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review