The Definitives

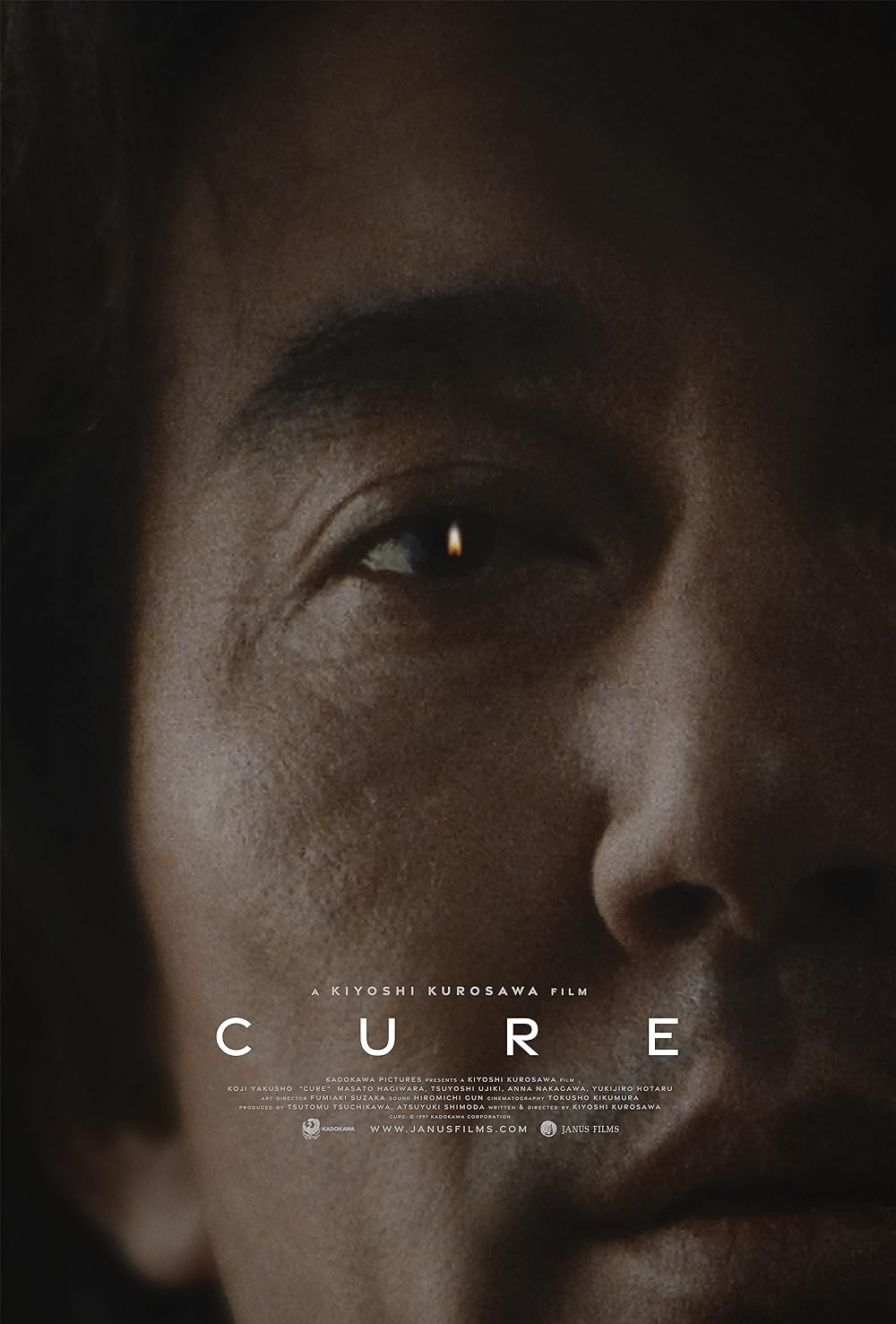

Cure (1997)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure takes its time implanting itself in your mind before completely taking you over, not unlike the mysterious killer at the film’s center. It resembles a traditional policier for the first hour, following a personally troubled but dogged detective out to uncover the truth behind a series of seemingly unrelated killings. Each victim has been slain with an “X” slashed into their neck and chest; in each case, someone different has confessed to the murder. Even so, there’s a lingering question about the connection between these murders and whether “the devil made them do it.” With a plot unfolding at a menacing yet measured pace, Cure relies on ambiguity and questions, subtle characterization, and an elusive atmosphere. It builds the mood slowly, starting like a typical 1990s serial killer potboiler but progressing in the key of a dark tone poem. Still, unlike similar material released by the Japanese studio system or any mainstream film industry, Cure is not merely an escapist yarn about a cop with an inextricable connection to a killer. That’s only the launchpad for something more sophisticated and undefinable. Kurosawa elevates the serial killer film by dwelling on theme and presentation, offering a picture that uses genre like a trap to ensnare the viewer in an experience of self-exploration.

Released in 1997, Cure is often described as a precursor to the J-Horror movement of the late 1990s, given some of its more grisly images and supernatural flourishes in the second half. But Kurosawa’s film has several distinct differences from the “original video” or “V-cinema” horror titles produced for videotape distribution, such as those by Takashi Miike (Bodyguard Kiba, 1993) and Takashi Shimizu (Ju-on, 2000). With their flat visuals and cheap video appearance, those films relied on the juxtaposition of sensational or otherworldly imagery displayed on the grainy and unremarkable home video format, thus imbuing the films with a certain ironic appeal. Cure does not have this aesthetic. Kurosawa’s uses of genre and time remain as complicated as his mise-en-scène, which looks and feels like cinema, and was made for and distributed on theatrical screens. Rather than the abrupt cutting and unstable framing of J-Horror, Kurosawa uses master shots extended for long periods, plunging the viewer into the action or lack thereof. He employs deliberate pacing to test his audience’s resolve, forcing us to attempt to figure it out. Though, his intentional narrative uncertainties prevent us from doing so in the manner of a textbook thriller. It’s an aesthetic more aligned with Claire Denis or Michelangelo Antonioni than the filmmakers of J-Horror. And the association seems to be a rather superficial one that considers only the appearance of bloodshed and a possible paranormal force.

Kurosawa has made nearly thirty theatrical features and plenty more for the Japanese video and television markets. His work includes various genres such as comedies, shoot-‘em-ups, science fiction, mystery, coming-of-age dramas, and spy-thrillers. Cure is often considered Kurosawa’s breakout film, representing his emergence from “pink films” (Kandagawa Pervert Wars, 1983)—a soft-core market where many Japanese filmmakers of Kurosawa’s generation received their start—and direct-to-video or “V-Cinema” (Yakuza Taxi, 1994) into the realm of so-called serious cinema. It was the first of Kurosawa’s films to be screened at international festivals, receive distribution outside of Japan, and be taken seriously by critics. The screening at the Toronto Film Festival in 1998, in particular, turned him into a name to remember, helping to establish him as a marketable filmmaker beyond Japan. He told IndieWire that he finally realized, “My films were international currency that could be understood and appreciated by people outside of Japan” and “I could make my own kind of film, set in Japan and make a unique contribution.” Perhaps that’s because the premise seems familiar and marketable to a 1990s audience overstuffed with Hollywood serial killer cinema.

Kurosawa has made nearly thirty theatrical features and plenty more for the Japanese video and television markets. His work includes various genres such as comedies, shoot-‘em-ups, science fiction, mystery, coming-of-age dramas, and spy-thrillers. Cure is often considered Kurosawa’s breakout film, representing his emergence from “pink films” (Kandagawa Pervert Wars, 1983)—a soft-core market where many Japanese filmmakers of Kurosawa’s generation received their start—and direct-to-video or “V-Cinema” (Yakuza Taxi, 1994) into the realm of so-called serious cinema. It was the first of Kurosawa’s films to be screened at international festivals, receive distribution outside of Japan, and be taken seriously by critics. The screening at the Toronto Film Festival in 1998, in particular, turned him into a name to remember, helping to establish him as a marketable filmmaker beyond Japan. He told IndieWire that he finally realized, “My films were international currency that could be understood and appreciated by people outside of Japan” and “I could make my own kind of film, set in Japan and make a unique contribution.” Perhaps that’s because the premise seems familiar and marketable to a 1990s audience overstuffed with Hollywood serial killer cinema.

In Cure, the presence of a criminal who uses mesmerization to convince his victims to kill reflects Hollywood’s obsession with serial killers in the 1990s. After its critical and commercial validation with The Silence of the Lambs (1991), the genre flourished over the next few years. Dozens of titles followed determined cops who hunted the hunters: Copycat (1995), Se7en (1995), Switchback (1997), Kiss the Girls (1997), and Summer of Sam (1998) saturated the marketplace. However, a supernatural element differentiates Cure from the standard serial killer fare. Although it doesn’t quite reach the level of, say, 1998’s Fallen, in which the killer’s spirit travels from host to host, carrying out his crimes in the guise of another, it does implant a tension between reality and something illusory. These genre elements serve as familiar trappings as opposed to strict rules that must be obeyed. Inevitably, Kurosawa breaks from genre models to achieve something personal and open-ended. Kurosawa told an interviewer from Midnight Eye, “I don’t start with a philosophical or thematical approach. Instead I often start with a genre that’s relatively easy to understand and then explore how I want to work in that genre. And that’s how a theme or an approach develops.”

Kurosawa was inspired to make Cure while watching the news. The authorities had just captured a murderer, and the media coverage showcased the criminal’s neighbors, who offered the sort of observations that have since become clichés. You know the sort: “He was a very nice person” or “He was the kind of guy you’d want your sister to marry”—two lines Ted Bundy’s friends used to describe him. Kurosawa began to wonder, What if what they’re saying is true? What if it wasn’t the murderer’s fault? What if someone influenced him to perform these killings? Such questions of identity and selfhood pervade Cure. Are we the sum total of our actions, or is there an interior self operating separately from our external being? Are we the same person at home and work, or do we become someone else? If people have an inherent duality between the interior and exterior, is it possible to purge oneself of the interior and exist as purely external? Kurosawa explores these ideas in ways that lead to haunting revelations, all derived from the most confronting question of all: Who are you?

The film follows Kenichi Takabe (Koji Yakusho), a detective searching for the link between several unconnected victims with an “X” carved into their flesh. The latest involves a man who beats a prostitute to death with a pipe before slicing her across the chest and neck, as if saying, “X marks the spot.” But then the killer hides in a nearby storage closet, where Takabe finds him naked, huddled into a fetal position, with no memories, but weeping from the sudden awareness of what he’s done. Stranger still, there doesn’t appear to be one perpetrator behind the killings. Other victims with “X” carved into them have no connection to their assailants. A man obsessed with finding order in life and taught to suppress his emotions, the ever-logical Takabe is perplexed by a case that doesn’t fit the usual schema. “All I want is to find words that will explain the crimes,” he says. “That’s my job.” His friend, the police psychiatrist Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), warns him not to look for logical explanations and questions whether crimes must have a purpose. “No one can understand what motivates a criminal,” Sakuma says, “sometimes not even the criminal.”

The film follows Kenichi Takabe (Koji Yakusho), a detective searching for the link between several unconnected victims with an “X” carved into their flesh. The latest involves a man who beats a prostitute to death with a pipe before slicing her across the chest and neck, as if saying, “X marks the spot.” But then the killer hides in a nearby storage closet, where Takabe finds him naked, huddled into a fetal position, with no memories, but weeping from the sudden awareness of what he’s done. Stranger still, there doesn’t appear to be one perpetrator behind the killings. Other victims with “X” carved into them have no connection to their assailants. A man obsessed with finding order in life and taught to suppress his emotions, the ever-logical Takabe is perplexed by a case that doesn’t fit the usual schema. “All I want is to find words that will explain the crimes,” he says. “That’s my job.” His friend, the police psychiatrist Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), warns him not to look for logical explanations and questions whether crimes must have a purpose. “No one can understand what motivates a criminal,” Sakuma says, “sometimes not even the criminal.”

Enter a seemingly aloof young man named Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), who wanders from place to place, outwardly detached from reality, regarding the world as though he’s seeing his surroundings for the first time. A schoolteacher meets Mamiya on a beach and assumes he’s an amnesiac. He brings him home, subjecting himself to Mamiya’s strange behavior: he shuts off lights, flicks on his lighter, and asks the schoolteacher questions. The next day, the schoolteacher slaughters his own wife. Mamiya repeats this pattern with a cop and doctor, and each encounter results in a brutal killing. When Takabe’s investigation identifies Mamiya as the common factor, he finds interrogation impossible. “Where is this?” Mamiya asks, almost in a fugue state. “Who are you?” And when the detective attempts to redirect the questions away from himself, Mamiya speaks in circles, turning every question back on the detective with infuriating ease. Eventually, they learn Mamiya was a graduate student who studied personality disorders and mesmerism—a precursor to hypnosis, conceived in the eighteenth century by Franz Mesmer, who believed in the transference of energy from one person to the next. Although at first Mamiya seems detached, Takabe realizes his behavior is intentionally designed to implant a murderous hypnotic suggestion in those around him. But perhaps brainwash is a better term since he seems to wipe clean his victim’s psychological blocks, leaving only a vessel.

At the same time, the worn-out detective must care for Fumie (Anna Nakagawa), his wife, who suffers from an unspecified form of dementia. The film’s first shot shows her reading aloud from Helmut Barz’s rendition of the folktale Bluebeard in a spare hospital room. Some time later, when a doctor asks about the book, she has no memory of it, as though her disorder has drained her mind of its contents just as Mamiya has done to his victims. Bluebeard is an obscure if telling choice on Kurosawa’s part. Broadly, the story follows the latest young wife of the titular nobleman, curious about the locked chamber he forbade her to enter. Overcome by her need to know the forbidden room’s contents, the young wife uses the key entrusted to her and discovers her husband’s previous wives butchered and hanging from hooks. When he learns that his wife defied him, Bluebeard plans to kill her too, but her brothers save her at the last moment. Her husband is slain, and she inherits his wealth. The moral of the story rests in knowledge itself. The key leads the young wife to new knowledge, which, given its horrifying nature, shatters her innocent perception of the world. It cannot be unseen. Even so, knowledge, even the grimmest of realizations, leads to prosperity. These themes will emerge by the end of Cure.

Takabe’s futile search for knowledge about Mamiya’s motivations or his wife’s illness echoes Kurosawa’s larger portrait of a dispassionate and disconnected society. Takabe admits to Sakuma that he’s been reading psychiatric texts to understand Fumie’s condition better, but it doesn’t help him get control. At home, Fumie continues to wander outside and turn on their dryer, absently performing these actions as if compelled by something deep in her mind he cannot understand. Worse, Takabe does not have the patience to try, not as the pressure of his case grows. Soon he must leave her with the equally detached doctor, who, in one session with Fumie, sits several feet away in a clinical room. The doctor’s method of therapy involves small talk of the lowest order. First, he asks Fumie about Bluebeard, then says, “Enough of the book, let’s talk about something else. How are you?” When Fumie responds with a short answer, he seems satisfied. With care like this, no wonder Fumie’s condition worsens. Such behavior is characteristic of Kurosawa’s ongoing critique of a disengaged culture—a theme he returns to in Pulse, symbolized by contemporary society’s overreliance on technology.

Takabe’s futile search for knowledge about Mamiya’s motivations or his wife’s illness echoes Kurosawa’s larger portrait of a dispassionate and disconnected society. Takabe admits to Sakuma that he’s been reading psychiatric texts to understand Fumie’s condition better, but it doesn’t help him get control. At home, Fumie continues to wander outside and turn on their dryer, absently performing these actions as if compelled by something deep in her mind he cannot understand. Worse, Takabe does not have the patience to try, not as the pressure of his case grows. Soon he must leave her with the equally detached doctor, who, in one session with Fumie, sits several feet away in a clinical room. The doctor’s method of therapy involves small talk of the lowest order. First, he asks Fumie about Bluebeard, then says, “Enough of the book, let’s talk about something else. How are you?” When Fumie responds with a short answer, he seems satisfied. With care like this, no wonder Fumie’s condition worsens. Such behavior is characteristic of Kurosawa’s ongoing critique of a disengaged culture—a theme he returns to in Pulse, symbolized by contemporary society’s overreliance on technology.

Kurosawa presents all of this in long master and medium shots that make the viewer an objective observer. He shoots scenes of gristly murder with the same distance he does Fumie and her doctor speaking. Another filmmaker might be compelled to stylize, and thus heighten, the violence for a greater impact. Kurosawa knows that depicting savage violence with a certain matter-of-factness, with less cinematic ornamentation, will have a more chilling effect. Then, without warning, Kurosawa breaks from his austere form to suggest that Takabe is not entirely immune to Mamiya’s ability to get into the heads of his victims. Flashes of animals from Mamiya’s apartment and a hallucination about Fumie’s suicide creep into Takabe’s mind. The aesthetic changes sharply to warp our expectations. We see the film’s long shots and measured editing interrupted by jarring images that cut into the film, reflecting Takabe’s susceptibility to hypnotic suggestion. From this point on, Cure remains in a state of duality between its beleaguered hero’s conscious and subconscious mind. Take a repeated shot that finds Takabe on a bus, where clouds, not buildings or pedestrians, stream by outside the windows. Does this image occur in reality from a strange angle? Or are we seeing Takabe travel between one frame of mind to the next, from a man troubled by his need for control to a man who embraces the chaos prescribed by Mamiya?

Between his elusive prime suspect and wife, with whom he grows increasingly frustrated, Takabe nears a breaking point. Kurosawa draws parallels between these two aspects of Takabe’s life, Fumie’s dementia and Mamiya’s empty-headed malice. Fumie is a shell of a person in her current state. And even though the killer is a masterful manipulator of people, his motivations remain a mystery to Takabe and the viewer. Mamiya seems to empty the minds of his victims, which in turn reduces them to their most primal selves. Sakuma argues that hypnotism won’t change a person’s basic morals or turn them into murderers, but there seems to be more than mere murder driving Mamiya. In his book about Kurosawa, Jerry White notes that Mamiya liberates his victims “from societal bounds by making murder morally acceptable.” Although Cure remains vague about the specifics, Mamiya unburdens those he brainwashes, allowing his victims to relieve themselves of their burdens and engage in chaos. Mamiya equates this process to rebirth when he promises Takabe, “You’ll be born again, just like me.” At this, we cannot help but think of the prostitute’s killer, who was found naked, hiding in a closet in a fetal position, as traumatized from his rebirth as a newborn child entering the world for the first time.

The title implies the presence of a disease. Kurosawa identifies the symptoms as the repression of our innate, violent selves—how society and law cause people to betray their root nature. The director told Kimberly Chun, “To be truly sane in society, it’s possible that one needs to escape the frameworks and the confines of our value system in society such as morality, law, and justice.” His point is that certain social obligations and expectations may prove unhealthy, and only by removing them through a drastic change can they be refashioned. This is the title’s cure and Mamiya’s plan. These ideas gnaw at Takabe, whose commitment to his roles of husband and detective eat away at him. And despite Sakuma’s warnings against it, Takabe finds himself drawn to Mamiya, who asks, “The detective or the husband? Which is the real you? Neither one is the real you. There is no real you.” Mamiya seems to ask questions not because he’s interested in the answers but because he wants his subjects to free themselves from their hangups and pass along the chaos cure. Although Takabe grows ever more enraged by the killer’s way of talking in circles and responding to every question with a question, he cannot help but vent his frustrations about Fumie and the emotional toll of being a detective. In a way, Kurosawa embraces the basic tenet of a serial killer movie: the connection between the cop and killer—the inescapable bond between Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter, or perhaps more appropriately given their fates, Det. Mills and John Doe. “You’re someone who can understand what I’m really saying,” Mamiya tells Takabe. But similar to the conclusion in Se7en, Takabe will both execute the killer and complete his highly orchestrated plan.

The title implies the presence of a disease. Kurosawa identifies the symptoms as the repression of our innate, violent selves—how society and law cause people to betray their root nature. The director told Kimberly Chun, “To be truly sane in society, it’s possible that one needs to escape the frameworks and the confines of our value system in society such as morality, law, and justice.” His point is that certain social obligations and expectations may prove unhealthy, and only by removing them through a drastic change can they be refashioned. This is the title’s cure and Mamiya’s plan. These ideas gnaw at Takabe, whose commitment to his roles of husband and detective eat away at him. And despite Sakuma’s warnings against it, Takabe finds himself drawn to Mamiya, who asks, “The detective or the husband? Which is the real you? Neither one is the real you. There is no real you.” Mamiya seems to ask questions not because he’s interested in the answers but because he wants his subjects to free themselves from their hangups and pass along the chaos cure. Although Takabe grows ever more enraged by the killer’s way of talking in circles and responding to every question with a question, he cannot help but vent his frustrations about Fumie and the emotional toll of being a detective. In a way, Kurosawa embraces the basic tenet of a serial killer movie: the connection between the cop and killer—the inescapable bond between Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter, or perhaps more appropriately given their fates, Det. Mills and John Doe. “You’re someone who can understand what I’m really saying,” Mamiya tells Takabe. But similar to the conclusion in Se7en, Takabe will both execute the killer and complete his highly orchestrated plan.

Not unlike Mamiya, Kurosawa asks questions and provides no answers. The equal measures of severity and ambiguity are what make Cure so engrossing. A boilerplate version of this film would go to great lengths to establish its complex series of narrative and existential questions, and then proceed to answer those questions and create closure, probably with a forced scene of exposition. Instead, Kurosawa’s approach borders on Socratic, posing questions through the narrative that every viewer must answer for themselves. To be sure, the nature of Mamiya’s cure for this social ailment is intentionally unclear. Does the cure present itself in a purging of one’s darkest desires through violent acts of murder alone? Does it emerge by surrendering oneself to become “a missionary sent to propagate the ceremony” held by a centuries-old cult of Mesmer, as a late plot development suggests? Does Takabe purge himself by executing the escaped Mamiya in cold blood or become another in a long line of “soul conjuring” vessels of the occult? A final scene suggests the contented-looking Takabe has adopted Miyama’s ability and uses it on a waitress, who ominously reaches for a knife. The irony is that, as a detective, he should be stopping crimes to create a sense of social order by curing society of crime. Now he’s curing society by purging people and giving them the capacity to act unhindered. The equivocation of the last haunting image lingers into the days, weeks, and months after watching Cure.

Oftentimes with genre, any genre, the deviations from the usual recipe are the most exciting. Cure’s tricky games of plot and form—standard in the genre that gave us films like Se7en—melt away into a much more intriguing psychological and existential puzzle. Kurosawa’s approach cannot help but recall Olivier Assayas’ Personal Shopper (2018), a supernatural mystery that similarly investigates a murder, transcendence, or possibly an emotional projection with equal amounts of ambivalence and resistance to closure, both in narrative and form. And yet, both films lack answers in a way that deepens their potential readings rather than limiting them to the constraints of typical genre fare released by major studios. This is sophisticated, personal filmmaking that defies any attempt to label it in conventional terms. Though it looks and at times feels like a police procedural and eventually a horror film, Cure leads to essential questions about what compels people to behave in a certain way, which versions of ourselves are real, and how, through such uncertainty, we can ever hope to feel settled in our lives with such questions—above all other questions, Mamiya’s recurring “Who are you?”—lingering in our subconscious.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Dave!)

Bibliography:

Bordwell, David. “The Other Kurosawa: Shokuzai.” DavidBordwell.net, 21 July 2013. http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2013/07/21/the-other-kurosawa-shokuzai/. Accessed 1 February 2021.

Mes, Tom. “Kiyoshi Kurosawa.” Midnight Eye, 20 March 2001. http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/kiyoshi-kurosawa/. Accessed 1 February 2021.

Mottesheard, Ryan. “Interview: Kurosawa’s ‘Cure’ for the Common Horror Film.” IndieWire, 1 Aug 2021. https://www.indiewire.com/2001/08/interview-kurosawas-cure-for-the-common-horror-film-80839/. Accessed 21 June 2021.

O’Rourke, Jim, and Kiyoshi Kurosawa. “Kiyoshi Kurosawa.” BOMB, no. 91, 2005, pp. 64–67. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40427198. Accessed 6 February 2021.

White, Jerry. The Films of Kiyoshi Kurosawa: Master of Fear. Stone Bridge Press, 2009.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review