The Definitives

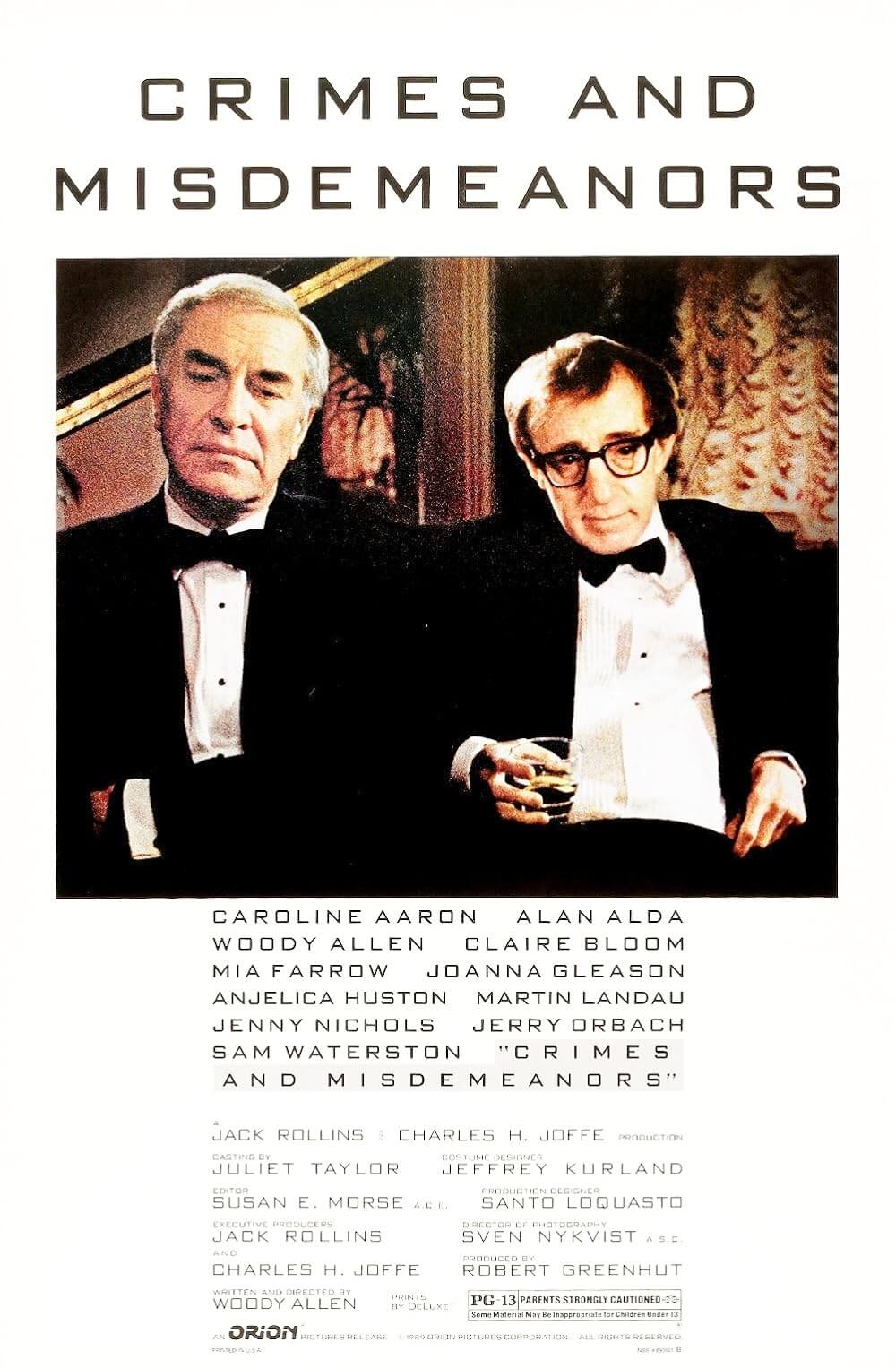

Crimes and Misdemeanors

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors, a rabbi named Ben (Sam Waterston) suffers from an eye disease and may lose his sight. Ben’s ophthalmologist, Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), has a thriving and privileged lifestyle, but Judah’s way of life is put at risk when his mistress, a lonely flight attendant named Dolores (Anjelica Huston), threatens to expose him as a philanderer and embezzler. Employing his brother’s shady connections, Judah opts to have Dolores killed. When he does, he has an inner debate about whether God will pass down some intrinsic moral justice with which he will be punished, or if humankind creates its own morality and thus, if one chooses not to recognize it, one cannot be punished by it. Meanwhile, an unhappily married, struggling documentary filmmaker named Cliff Stern (Allen) pines after his charming production assistant, Halley (Mia Farrow), while making a piece about his wife’s self-absorbed brother, Lester (Alan Alda), a television producer whose ego is only outmatched by his success. As Cliff’s marriage grows more distant, he attempts to affirm his love with Halley, while his contempt for Lester and his romantic outlook leave him blind to how life rarely works out like it does in the movies.

Indeed, by the end, the doctor has gotten away with murder and lives at peace with his actions; the filmmaker realizes his worst fears when he learns Lester and Halley are engaged; and the rabbi, seemingly the only character capable of seeing God’s wisdom through these horrible events, goes completely blind. To call this film bleak is an understatement. Released in 1989, at first glance Crimes and Misdemeanors appears almost dichotomous in structure, as though Allen has resolved to tell two stories: One, a murder-centric morality play, centers on Judah (and boasts Landau’s Oscar nominated performance) and assumes a weighty existential substance; the other follows Cliff and emits a deceptively comical tone. One might even call the structure symbolic of tragedy and comedy in the sock and buskin sense, as though Allen had intended to marry the two forms in a single narrative. But this is not the case. Shot in long, penetrative takes by Ingmar Bergman’s longtime cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, Allen’s film uses a novelistic style he employed previously for Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and settles on an ensemble cast to enable a discussion of death and morality—customary themes for Allen’s authorship, but never with such absorption and potency.

Tolstoy wrote in War and Peace, “The only absolute knowledge attainable by man is that life is meaningless.” Allen referenced this line in Hannah and Her Sisters, but perhaps it also belongs in Crimes and Misdemeanors, whose structure and themes recall the Russian literature that Allen so often quotes and alludes to in his films—the works of Dostoyevsky and Chekov and existential writers who have given up on any hope of order or fairness to the universe. Allen even wrote part of the film’s script during a vacation that began with a disastrous stop in Russia, but later segued into Europe. Allen considers himself “a reluctant but pessimistic agnostic”, meaning he would like to believe that something out there exists, but he does not, and he wishes this was not the case. His recurrent exploration of death and the meaninglessness of the universe amid God’s silence recalls a similar investigation made by Ingmar Bergman—Allen’s oft-referenced favorite filmmaker—in The Seventh Seal (1957) and other films. But while Bergman uses enriched metaphors of time and setting, Allen seeks a contemporary and comparably realistic set of characters and circumstances to reach the same conclusions in this film. Most assessments of Allen’s work list Interiors (1978) and September (1987) among his most Bergmanesque films in tone, but Crimes and Misdemeanors remains the most Bergmanesque in theme.

Tolstoy wrote in War and Peace, “The only absolute knowledge attainable by man is that life is meaningless.” Allen referenced this line in Hannah and Her Sisters, but perhaps it also belongs in Crimes and Misdemeanors, whose structure and themes recall the Russian literature that Allen so often quotes and alludes to in his films—the works of Dostoyevsky and Chekov and existential writers who have given up on any hope of order or fairness to the universe. Allen even wrote part of the film’s script during a vacation that began with a disastrous stop in Russia, but later segued into Europe. Allen considers himself “a reluctant but pessimistic agnostic”, meaning he would like to believe that something out there exists, but he does not, and he wishes this was not the case. His recurrent exploration of death and the meaninglessness of the universe amid God’s silence recalls a similar investigation made by Ingmar Bergman—Allen’s oft-referenced favorite filmmaker—in The Seventh Seal (1957) and other films. But while Bergman uses enriched metaphors of time and setting, Allen seeks a contemporary and comparably realistic set of characters and circumstances to reach the same conclusions in this film. Most assessments of Allen’s work list Interiors (1978) and September (1987) among his most Bergmanesque films in tone, but Crimes and Misdemeanors remains the most Bergmanesque in theme.

Though at times hilarious, Allen’s script never settles into pure comedy, even during Cliff’s scenes. Rather, it balances strains of tragedy and comic tragedy, marked by the film’s score that alternates between heavy Schubert and airier jazz selections. The film’s final coda, which takes place at the wedding of Ben’s daughter, brings these characters together and reveals through each how the universe is a cold, unjust place, and further annihilates any possibility of interpreting the film as a comedy. Instead of comedy and tragedy, Allen considers other oppositional forces. For example, in the Judah story, he questions the validity of religion against morality as a man-made contrivance. In both stories, Allen compares the ways in which we view ourselves versus the way others see us, the way the higher classes are usually corrupt and the lower classes naïve. But most of all, Allen questions the differences between reality and the fantasies we create; be it God, our fantastic belief that life imitates art, or our delusions that life should work out a certain way because we will it to. In this sense, Allen, though working in a format rich with symbolism and story developments otherwise associated with a dramatic un-reality, offers a film that is rooted in “the real” in terms of how the story unfolds for its characters in relation to the author’s views.

In the opening scene, Judah gives a speech at a banquet in his honor. He has just overseen the opening of a new ophthalmology wing in his hospital, and he relates a story about what his father told him as a boy: “The eyes of God are constantly watching us.” Much later, his father’s lesson haunts Judah after he has Dolores killed. He remembers how as a boy his Jewish family had intense dinner table discussions about the origins of religion and morality. In an imagined debate or perhaps distant memory, Judah sees his father arguing that morality is impelled by God, who sees to it that the unjust are punished. Judah’s aunt, however, says a person creates their own sense of guilt; a murderer, if he could live with the guilt, could easily kill and no such “God” would punish him. Though he is now, or so he thought, an atheist, Judah, whose ironic biblical name has grand implications, cannot help question what he has done and if God will punish him. But then, Judah’s initial doubts are just a part of his process of rationalization, which began before he ever openly discussed Dolores’ murder.

In the opening scene, Judah gives a speech at a banquet in his honor. He has just overseen the opening of a new ophthalmology wing in his hospital, and he relates a story about what his father told him as a boy: “The eyes of God are constantly watching us.” Much later, his father’s lesson haunts Judah after he has Dolores killed. He remembers how as a boy his Jewish family had intense dinner table discussions about the origins of religion and morality. In an imagined debate or perhaps distant memory, Judah sees his father arguing that morality is impelled by God, who sees to it that the unjust are punished. Judah’s aunt, however, says a person creates their own sense of guilt; a murderer, if he could live with the guilt, could easily kill and no such “God” would punish him. Though he is now, or so he thought, an atheist, Judah, whose ironic biblical name has grand implications, cannot help question what he has done and if God will punish him. But then, Judah’s initial doubts are just a part of his process of rationalization, which began before he ever openly discussed Dolores’ murder.

When Judah first meets with his brother, Jack (Jerry Orbach), to discuss his Dolores predicament, he explains that she has become unreasonable, that she has attempted to contact his wife (Claire Bloom), and that she wants their fading relationship in the open. When Judah refused, she threatened him with blackmail. He asks his brother for advice, but Jack’s recommendation of having someone talk to her is not enough. When Jack then suggests murder, Judah plays as if taken aback, perhaps because he wants to believe that his hoodlum brother conceived the idea. That would be easier than to acknowledge his own premeditation. But Judah has driven the conversation to this point. Why else would he contact his estranged brother with criminal ties, unless he wanted Jack to propose killing Dolores? Judah’s plight becomes one of rationalizing the murder and slithering his way into an almost victimized position. To live with such a crime, first he must convince himself it was Jack’s idea to begin with; second, he must eliminate any thoughts of guilt by admitting to himself that no matter his religious upbringing, God remains a fabrication, and with Him, morality. If this is true, then Judah has only to forget what he has done and live his life, and he will have gotten away with the perfect murder.

A component of Judah’s rationalization involves a dreamed conversation with the rabbi, Ben. Although earlier in the film Judah discusses with Ben how Dolores has threatened the stability of his marriage, he has mentioned nothing of her further blackmail or his own plans of murder. Judah is too careful for that, and instead, he imagines a conversation with Ben in which he deliberates on the question of morality in plotting a murder, and whether or not he will be punished by God. After the discussion, wherein Ben takes the position of Judah’s father, Judah finally tells his imaginary Ben, “Jack lives in the real world. You live in the kingdom of heaven.” Judah’s father once said that he would choose God over Truth. Judah is the opposite, as God would judge his actions as immoral in this case. Truth, however, is ambivalent to any number of atrocities, not the least of which is murder. And so, Judah must take the path of Truth as defined by his aunt—it is the path that allows Judah’s comfortable life to proceed uninterrupted, and without the fear of punishment from some intangible force.

A component of Judah’s rationalization involves a dreamed conversation with the rabbi, Ben. Although earlier in the film Judah discusses with Ben how Dolores has threatened the stability of his marriage, he has mentioned nothing of her further blackmail or his own plans of murder. Judah is too careful for that, and instead, he imagines a conversation with Ben in which he deliberates on the question of morality in plotting a murder, and whether or not he will be punished by God. After the discussion, wherein Ben takes the position of Judah’s father, Judah finally tells his imaginary Ben, “Jack lives in the real world. You live in the kingdom of heaven.” Judah’s father once said that he would choose God over Truth. Judah is the opposite, as God would judge his actions as immoral in this case. Truth, however, is ambivalent to any number of atrocities, not the least of which is murder. And so, Judah must take the path of Truth as defined by his aunt—it is the path that allows Judah’s comfortable life to proceed uninterrupted, and without the fear of punishment from some intangible force.

After searching for God and finding Him nowhere, Allen has long since determined that one must find their place in the world by supplying it with love. Throughout his films, his characters frequently counteract the bitter world with fleeting moments of happiness and romance and sex, and in a sense, they each explore—to borrow another symbol from ancient Greece—the relationship between the darkness of Chaos and its illumination with the arrival of Eros. This theme permeates in Allen’s films from Annie Hall (1977) all the way through Midnight in Paris (2011). In Crimes and Misdemeanors, the character Dr. Louis Levy, a fictional philosophy professor played by real-life psychoanalyst Martin S. Bergmann, argues “The universe is a pretty cold place. We invest it with our feelings.” Of course, by the end, Levy, a man whose life’s work it was to preach the importance of love and who Cliff so admired, commits suicide unexpectedly. Allen forgoes his usual romantic notion that everyone finds love, and in its place, he dwells on his most cynical, hopeless assessment yet.

While Judah’s story has a chilling arc, Cliff’s is almost more painful to accept because of its initial, comparably light mannerisms. Roger Ebert described the transition as “Shakespearean: The crimes of kings are mirrored for comic effect in the foibles of the lower orders.” In some respect Ebert’s assessment is accurate. Certainly, Allen intended to compare classes in the film, but he does so by contrasting the social positions of Cliff and Lester, not Cliff and Judah. The relationship between Judah and Cliff is relative in that Judah is best associated with Lester, and Cliff is better aligned with Dolores—the two men of power (Judah and Lester) and their victims (Dolores and Cliff). In another way, Cliff’s arc implies that the high drama of Judah’s tale has a realistic correlation to everyday life, that Judah’s tale is not “just a murder story” and these sorts of hopeless turns happen up and down the social ladder. As such, Cliff’s story is much more than a mere reflection of Judah’s; it presents one of two unique illustrations of Allen’s thesis on the unfair order of the universe. Ebert’s assessment presupposes that Judah’s story takes precedence over Cliff’s, whereas Allen’s novelistic structure designates no single protagonist.

While Judah’s story has a chilling arc, Cliff’s is almost more painful to accept because of its initial, comparably light mannerisms. Roger Ebert described the transition as “Shakespearean: The crimes of kings are mirrored for comic effect in the foibles of the lower orders.” In some respect Ebert’s assessment is accurate. Certainly, Allen intended to compare classes in the film, but he does so by contrasting the social positions of Cliff and Lester, not Cliff and Judah. The relationship between Judah and Cliff is relative in that Judah is best associated with Lester, and Cliff is better aligned with Dolores—the two men of power (Judah and Lester) and their victims (Dolores and Cliff). In another way, Cliff’s arc implies that the high drama of Judah’s tale has a realistic correlation to everyday life, that Judah’s tale is not “just a murder story” and these sorts of hopeless turns happen up and down the social ladder. As such, Cliff’s story is much more than a mere reflection of Judah’s; it presents one of two unique illustrations of Allen’s thesis on the unfair order of the universe. Ebert’s assessment presupposes that Judah’s story takes precedence over Cliff’s, whereas Allen’s novelistic structure designates no single protagonist.

As Allen’s character endlessly quips in the actor’s usual wit, Cliff represents the common man, an idealist whose dreams are perceived as noble and who, unlike Judah, has no legacy to protect. As a documentary filmmaker, Cliff’s only claim to fame is a participation award in an obscure European film festival. His cold wife, Wendy (Joanna Gleason), has two brothers; one of them is the rabbi, Ben, and the other is Lester, whom she calls “a saint” because “he’s respected in his industry and he’s a millionaire.” The requirements for sainthood are not high in Wendy’s world. As a favor, Wendy asks her famous brother to let Cliff direct a television special being made about Lester’s career as an influential creator of sitcoms. For the money to finish his own documentary on Dr. Louis Levy, Cliff reluctantly agrees to the job and the shoot takes them around various locations in New York City. Alda portrays Lester as one of cinema’s all-time most contemptible characters, the actor deliciously self-confident and egomaniacal in the role. Lester carries a small voice recorder with him for periodic mental notes, but in each case, the note furthers his character’s vain and self-important persona. With a smile, he tells Cliff that he only agreed to allow him to direct the project as a favor to his sister. Then, right in front of Cliff, Lester stops to make a note, “Idea for farce: A poor loser agrees to do the story of a great man’s life and in the process comes to learn deep values.” Lester views Cliff as a loser and seems to enjoy telling him as much. As the shooting of Lester’s documentary commences, we see his grand opinion of himself on display. He sermons on the structure of comedy as if he invented it (“If it bends, it’s funny, if it breaks it’s not funny” or “Comedy is tragedy plus time”). He always seems to be promoting the career of some beautiful young airhead, whom he’s no doubt sleeping with. And he never misses an opportunity to remind those below him about his numerous Emmys and his other various accolades.

During the shoot, Cliff meets Halley, a sweet production assistant who shares his interest in Dr. Levy and suggests Cliff’s documentary might have a chance at making her show’s fall schedule. Cliff quickly falls in love and considers leaving Wendy for her. But in the course of filming, Cliff comes to believe that Lester wants Halley too—but just as one of his conquests. “I can tell,” he avows. He begins to build up to his eventual move on Halley while ignoring the signs of her growing romance with Lester, and when Cliff finally tries to kiss her, she lets him down easy. He warns Halley of Lester’s womanizing ways and she gives him indulgent responses, never confirming that she agrees with Cliff’s assessment, and subtly pandering to his comments without addressing them. This is because she does not agree, and even later falls in love with Lester. “He’s not what you think,” she explains. “He’s wonderful. He’s warm and caring and romantic.” Cliff can only reply, “He’s a success. He’s rich and he’s a success… This is my worst fear realized.” The expression of defeat and devastation on Allen’s face at this moment may be his very best piece of dramatic acting.

During the shoot, Cliff meets Halley, a sweet production assistant who shares his interest in Dr. Levy and suggests Cliff’s documentary might have a chance at making her show’s fall schedule. Cliff quickly falls in love and considers leaving Wendy for her. But in the course of filming, Cliff comes to believe that Lester wants Halley too—but just as one of his conquests. “I can tell,” he avows. He begins to build up to his eventual move on Halley while ignoring the signs of her growing romance with Lester, and when Cliff finally tries to kiss her, she lets him down easy. He warns Halley of Lester’s womanizing ways and she gives him indulgent responses, never confirming that she agrees with Cliff’s assessment, and subtly pandering to his comments without addressing them. This is because she does not agree, and even later falls in love with Lester. “He’s not what you think,” she explains. “He’s wonderful. He’s warm and caring and romantic.” Cliff can only reply, “He’s a success. He’s rich and he’s a success… This is my worst fear realized.” The expression of defeat and devastation on Allen’s face at this moment may be his very best piece of dramatic acting.

In both Judah and Cliff’s stories, there are thriving men of power who are corrupt and get away with murder or offenses relative thereto. Allen sees the world as an inequitable place where those in power get away with high crimes and smaller, more personal injustices, while the lower classes are stepped on in the process. In each case, these men of power seem aware of their own crimes, and it becomes their willingness to accept a life of transgression that leads them to success, whereas the morality of smaller men like Cliff holds them back. (This is not to suggest Cliff, or even Dolores, are wholly innocent; merely that their class prevents them from being corrupt on a grand scale.) In Judah’s case, he accepts his status as a pillar of his community and defends it against Dolores’ threat. He could have simply come clean to his wife and defused Dolores’ rage, but one of the reasons he refuses to admit his affair is because his wife would be crushed. “She worships me,” he says, and Judah could never live a life in which he did not feel exalted. As for Lester, he sees himself on the rough cut of Cliff’s footage, in which he’s shown seducing one of his young actresses; Cliff’s cutting compares Lester to Mussolini and an actual jackass, and so Lester fires Cliff. Nevertheless, Lester is content; the world views him as a success and he knows it, and he knows that the world will forever see Cliff as a loser.

With no accurate perception of the world, Cliff does not see himself as a failure. He spends his afternoons escaping to old moviehouses and into romantic films, at once convinced that they are fantasy, but at the same time he unconsciously expects life to work out like a Hollywood movie. Dolores lives under the same delusions. Consider one of Allen’s transitions as he cuts from Judah and Jack plotting Dolores’ murder to Cliff and Halley in the cinema watching a scene from This Gun for Hire (1942) where two men scheme to bump off another. Cliff leans over to Halley, “This only happens in the movies.” This ironic transition repeats itself several times in the film, where Allen differentiates between reality and fantasy by cutting to Cliff, in a moviehouse, watching some 1940s gem that loosely relates to a moment shown just before with Judah’s murder story. In a theme Allen explored so thoroughly in The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), he acknowledges that cinema provides an escape from reality, and indeed Cliff depends on that quality and has lost himself in it. His awareness of cinema’s power has become an unconscious expectation that his life should play out in a dreamy fashion. He is blind to reality. When he confesses his love to Halley, she denies him and later explains she intends to move to London for several months and complete some projects there. In the interim, Cliff’s marriage comes to an end and, somehow still hopeful, he believes he and Halley will be together for a romantic ending, just like in the movies.

With no accurate perception of the world, Cliff does not see himself as a failure. He spends his afternoons escaping to old moviehouses and into romantic films, at once convinced that they are fantasy, but at the same time he unconsciously expects life to work out like a Hollywood movie. Dolores lives under the same delusions. Consider one of Allen’s transitions as he cuts from Judah and Jack plotting Dolores’ murder to Cliff and Halley in the cinema watching a scene from This Gun for Hire (1942) where two men scheme to bump off another. Cliff leans over to Halley, “This only happens in the movies.” This ironic transition repeats itself several times in the film, where Allen differentiates between reality and fantasy by cutting to Cliff, in a moviehouse, watching some 1940s gem that loosely relates to a moment shown just before with Judah’s murder story. In a theme Allen explored so thoroughly in The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), he acknowledges that cinema provides an escape from reality, and indeed Cliff depends on that quality and has lost himself in it. His awareness of cinema’s power has become an unconscious expectation that his life should play out in a dreamy fashion. He is blind to reality. When he confesses his love to Halley, she denies him and later explains she intends to move to London for several months and complete some projects there. In the interim, Cliff’s marriage comes to an end and, somehow still hopeful, he believes he and Halley will be together for a romantic ending, just like in the movies.

Allen brings Judah and Cliff’s stories into harmony at the wedding of Ben’s daughter. Four months have passed, and we find Judah’s existential searching has faded away and he appears blissful and without concern. He has accepted the godless world and buried his guilt. Cliff’s deluded hope that Halley would return from London and their courtship would resume is destroyed when he sees Halley and Lester together. They are engaged. Cliff is overcome. Cliff and Judah each drift away from the reception and stumble upon one another. They talk about Cliff’s career in the movies, and Judah says he has a great “murder plot” for Cliff. Detailing his murder of Dolores as though it was fiction, Judah explains how the man in his story, plagued by guilt and questions of God’s moral justice, awakens one morning and “the sun is shining, his family is around him and mysteriously, the crisis has lifted.” Cliff wonders if someone could ever really live with such a thing on their conscience, having seen so many film noirs where the protagonist’s crimes tragically lead them to their demise. Judah responds, “This is reality. In reality we rationalize, we deny, or we couldn’t go on living.” In movies, in fiction, people turn themselves in for tragic effect; in reality, people like Judah get away with murder and bury their sins, people like Lester get the girl, and people like Cliff are ruined.

In the end, Crimes and Misdemeanors is not about Cliff’s tale reflecting Judah’s, but a more comprehensive lesson on our skewed perceptions and unrealistic expectations of the universe. Allen arrives at the conclusion that people are incapable of seeing the world in its true, unforgiving form, and so he consciously adopts the theme of blindness. At the wedding, we see that Judah was unable to cure Ben’s disease. Ben—who so believes in “a moral structure with real meaning and forgiveness and some kind of higher power”—is now blind. In symbolic terms, Ben’s optimism inflamed his blindness, as he was unable to see how uncaring the world really is. Allen uses the metaphor of shut eyes earlier when Judah visits the scene of the crime to recover some incriminating material in Dolores’ apartment; he sees Dolores’ dead body staring off into nothingness, and he closes her eyelids. She was blind to think Judah would allow her to destroy his life, just as Cliff was blind for not seeing the signs of Halley and Lester’s romance. In a way, Allen envies such blindness and wishes he could have faith that people are basically good and God is looking down on us. Because the alternative, the Truth, is so merciless and cruel.

In the end, Crimes and Misdemeanors is not about Cliff’s tale reflecting Judah’s, but a more comprehensive lesson on our skewed perceptions and unrealistic expectations of the universe. Allen arrives at the conclusion that people are incapable of seeing the world in its true, unforgiving form, and so he consciously adopts the theme of blindness. At the wedding, we see that Judah was unable to cure Ben’s disease. Ben—who so believes in “a moral structure with real meaning and forgiveness and some kind of higher power”—is now blind. In symbolic terms, Ben’s optimism inflamed his blindness, as he was unable to see how uncaring the world really is. Allen uses the metaphor of shut eyes earlier when Judah visits the scene of the crime to recover some incriminating material in Dolores’ apartment; he sees Dolores’ dead body staring off into nothingness, and he closes her eyelids. She was blind to think Judah would allow her to destroy his life, just as Cliff was blind for not seeing the signs of Halley and Lester’s romance. In a way, Allen envies such blindness and wishes he could have faith that people are basically good and God is looking down on us. Because the alternative, the Truth, is so merciless and cruel.

Placing Crimes and Misdemeanors within Woody Allen’s filmography becomes a matter of determining which themes from which films are encapsulated and focused by this one. Just as Annie Hall does with Allen’s comedic material, this film concentrates Allen’s weightier themes into a singular work. Thematic strains from Love and Death (1975), Interiors, The Purple Rose of Cairo, and September come into view here with astounding power. After Annie Hall, many of Allen’s films would leave audiences questioning whether what they have just seen is a comedy or drama. Few of them can be summed up so easily. Nearly each Allen film makes its audience laugh, yet at the same time, it exposes some vital, affecting lesson about life. Each film is unique and personal and contains multiple layers, and arguably none more so than Crimes and Misdemeanors. He achieves a picture of such consequence that it demands comparisons to the best selections in Bergman’s oeuvre, or more recently to the Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man. Allen’s entrenched views on the meaninglessness and coldness of the universe surface throughout his prolific career, but the dramatic affect has never had more resonance.

A subplot involving Cliff’s sister, the recent widow Barbara (Caroline Aaron), finds her searching for love in personals ads. She meets a man and they enjoy several dates. One night, after having too much to drink, the man proposes tying her up and making love to her. Lonely and desperate for a connection, she agrees. But instead of making love to her, he ties her down and then sits over her and defecates on her. This is the compressed version of the lesson offered by Crimes and Misdemeanors, that more often than not when you go out into this cruel world seeking meaning or even just plain fairness, the world responds by shitting on you. In the final scene, after recounting his murder plot, Judah tells Cliff, “If you want a happy ending, you should go see a Hollywood movie.” And here, Woody Allen has not made a Hollywood movie; he has made an important work of art that raises existential and moral questions. While hoping that through our anguish we will find some kind of happiness, Allen concedes to the reality of the indifferent universe with uncompromising honesty and despair.

Bibliography:

Allen, Woody; Björkman, Stig. Woody Allen On Woody Allen. New York: Grove Press, 2005.

Blake, Richard A. Woody Allen: Profane and Sacred. University of Michigan: Scarecrow Press, 1995.

Ebert, Roger. “Great Movies: Crimes and Misdemeanors.” RogerEbert.com. September 11, 2005.

Fox, Julian. Woody: Movies from Manhattan. New York: Overlook Press, 1996.

Lax, Eric. Conversations with Woody Allen. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

Lax, Eric. Woody Allen: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review