The Definitives

Clueless (1995)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

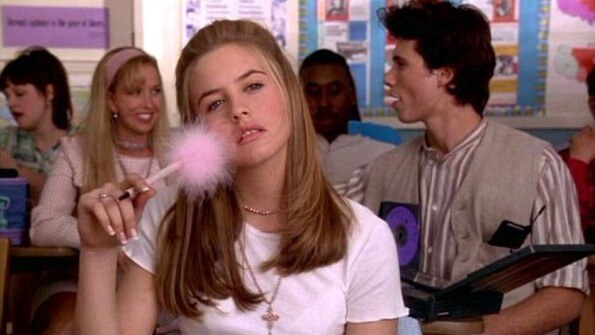

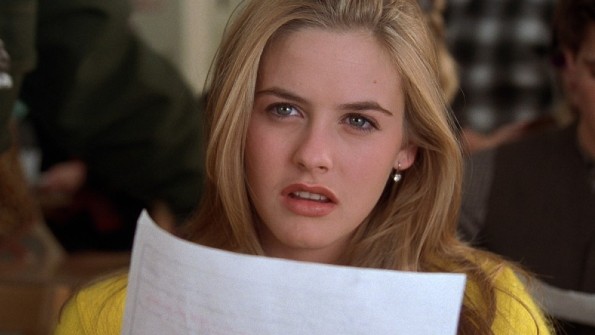

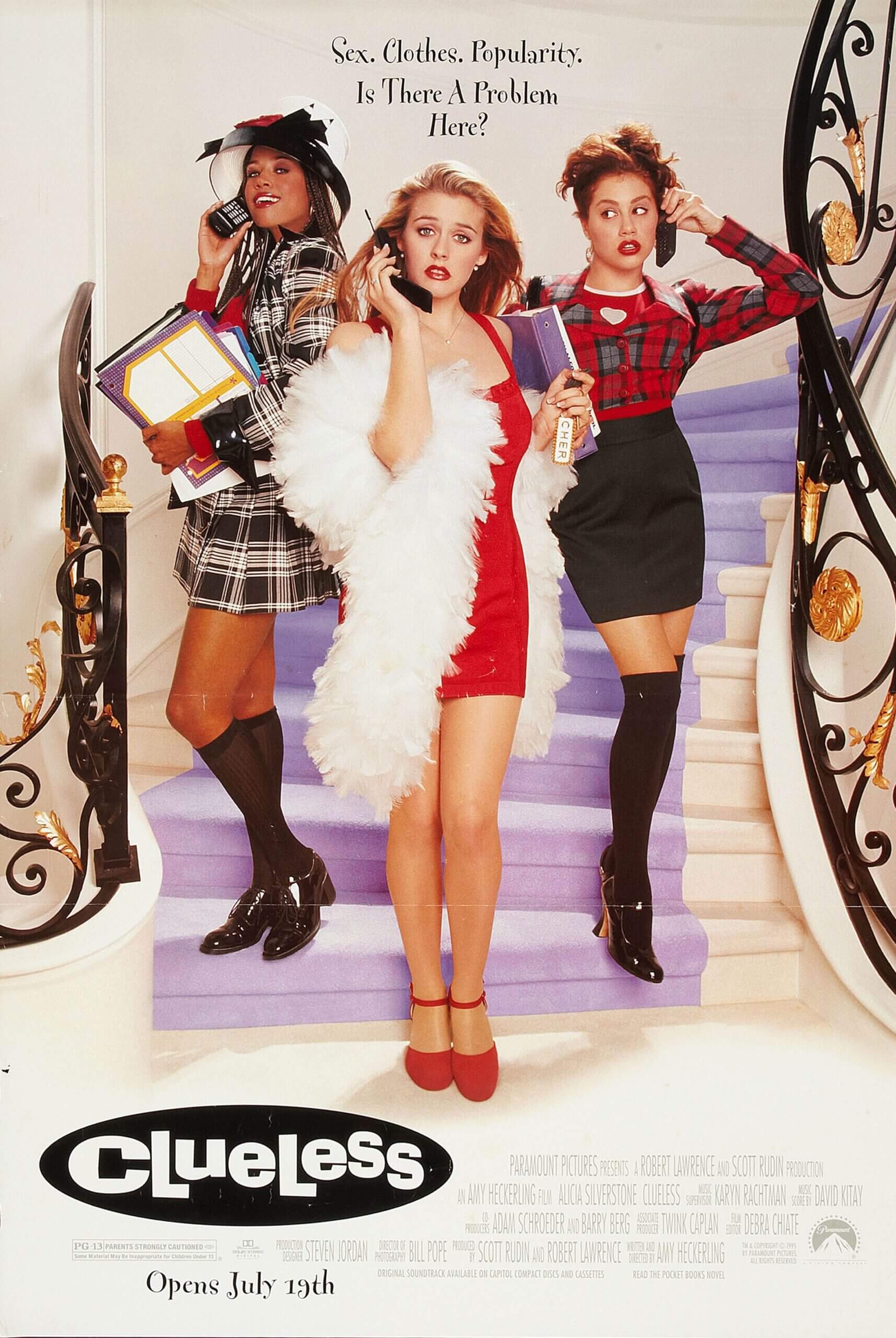

Satirical yet earnest, ironic yet heartfelt, optimistic yet never cloying, Amy Heckerling’s Clueless is the rare teen romantic comedy that lasts because of its complexity. The writer-director imbues the material with positivity, colorful clothes, bright titles, and sunshine; yet, like all comedies that stand the test of time, it seems to be about much more than its surface. Clueless remains a landmark for many reasons: it introduces a younger audience to Jane Austen, whose Emma informed Heckerling’s script; it established a new trend in Hollywood of translating classical literature to a contemporary high-school setting; its fashion helped define a generation; and its distinctive slang and attractive cast permeated the zeitgeist for years to come. And then there’s Cher Horowitz, played with pitch-perfect obliviousness and comic timing by Alicia Silverstone. Cher is the living embodiment of a certain corner of 1990s culture—the product of wealth, idleness, and regular doses of Beverly Hills, 90210. But Heckerling uses the character to critique privilege even while allowing Cher to engage in self-reflection, making her a timeless character whose willingness to grow proves redeeming. With a confident irony that never robs its characters of their integrity, Heckerling takes Clueless into a realm that both comments on and inhabits the teen movie archetype, so that what’s left goes beyond the genre’s conventions and builds upon them.

Clueless arrived in theaters in 1995, a decade after John Hughes blueprinted the teen genre with Sixteen Candles (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985), and Pretty in Pink (1986). Heckerling carved a face into the Mount Rushmore of ‘80s high-school comedies, too, with Fast Times at Ridgemont High in 1982. Most examples from this era involve snobs acting superior to so-called losers, who were usually the main characters, looking in from the outside. Take Heathers (1988), a brooding and macabre satire featuring Christian Slater and Winona Ryder as rebellious anti-establishment students who slay their elitist classmates. More forgiving was Valley Girl (1983), which recognized the sympathetic side of rich girls in a Romeo and Juliet-style romance between the titular Deborah Foreman and Nicholas Cage’s punkish slacker. Similarly, Can’t Buy Me Love (1987) saw roles reversed when the nerdy Patrick Dempsey buys his way into the cool crowd by paying Amanda Peterson to pretend to be his girlfriend for a month, and eventually, they fall for each other for real. The examples go on and on, most creating a clear social hierarchy that casts the upper-class rich and cool kids as villains and the poor losers and outcasts as the protagonists. But in both of her teen comedies, Fast Times and Clueless, Heckerling equalizes such polarized thinking and avoids reinforcing commonplace stereotypes.

The film centers on Cher, a superficial 16-year-old from Beverly Hills, who is stereotypically girly and preoccupied with shopping, fashion, and makeovers. Although Heckerling parodies Cher’s world of fresh nose jobs, pervasive cell phones, caloric complexes, and rampant privilege, the character is more than a “ditz with a credit card.” Cher is also intelligent and capable of growth, even if she’s often ill-informed and ignorant of everything outside of her social bubble. Heckerling presents this as Cher’s central flaw. With the help of her best friend Dionne (Stacey Dash)—who continuously bickers with her boyfriend Murray (Donald Faison)—Cher orchestrates a love connection between two teachers, her debate instructor Mr. Hall (Wallace Shawn) and the mousy Miss Geist (Twink Caplan), with some well-meaning fibs and a slight makeover. Intended to increase her “C” in debate class by helping her teachers find love, Cher’s successful scheme confirms her belief that she’s a matchmaker and sculptor of people. Cher then sets her sights on making over the new transfer student, Tai (Brittany Murphy), in her image. Even though Tai has chemistry with the stoner-skater Travis (Breckin Meyer), Cher tries to set her up with a boy from the cool crowd, Elton (Jeremy Sisto), who’s later revealed to be a jerk and, in Cher’s words, “a snob and a half.” Meanwhile, Cher finds herself drawn to Christian (Justin Walker), whose James Dean looks and ‘50s mannerisms barely conceal that he’s gay—a detail Cher fails to notice.

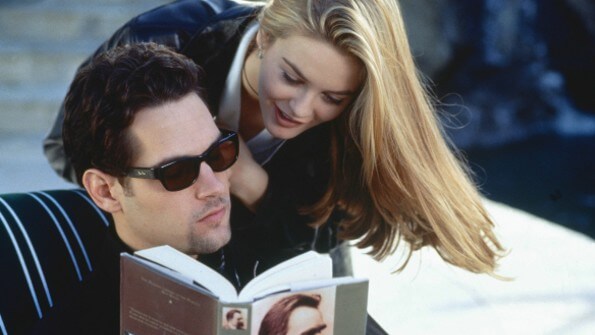

Heckerling performs an incredible balancing act in Clueless. She pokes fun at Cher’s world of absurd wealth and privilege, yet she also offers tenderness (cue the General Public song “Tenderness” over the end credits). Cher lives with her high-powered attorney father, Mel (Dan Hedaya), whose curmudgeonly yelling and apparent love for his daughter are endearing. And while Cher’s mother may have died in a comical “freak accident during a routine liposuction,” her absence is deeply felt. For all of Cher’s hilarious whining and bratty sensibilities, Heckerling never turns Cher into a monster, in part thanks to Silverstone’s cheery presence. But once Cher fails her driver’s license exam, she questions herself and her ability to assess others, wondering what else she’s been oblivious to and who else she got wrong. She resolves to change her ways (“I decided I needed a complete makeover, except this time, I’d make over my soul”) by first arranging a Pismo Beach disaster charity drive (one of Heckerling’s subtlest jokes), and then helping Tai find love with Travis. Eventually, Cher considers Josh (Paul Rudd)—her older ex-stepbrother from college, who’s interested in social responsibility, black clothes, Radiohead, and poolside Nietzsche—and realizes she’s in love. And what’s more, she has loved Josh all along. Their playfully mocking dynamic throughout the film recalls the classic love-hate relationship of Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night (1932). He calls out her spoiled behavior (“Who watching the galleria?”), and she insults his pretensions. But their mutual affection somehow works as romantic chemistry.

Heckerling performs an incredible balancing act in Clueless. She pokes fun at Cher’s world of absurd wealth and privilege, yet she also offers tenderness (cue the General Public song “Tenderness” over the end credits). Cher lives with her high-powered attorney father, Mel (Dan Hedaya), whose curmudgeonly yelling and apparent love for his daughter are endearing. And while Cher’s mother may have died in a comical “freak accident during a routine liposuction,” her absence is deeply felt. For all of Cher’s hilarious whining and bratty sensibilities, Heckerling never turns Cher into a monster, in part thanks to Silverstone’s cheery presence. But once Cher fails her driver’s license exam, she questions herself and her ability to assess others, wondering what else she’s been oblivious to and who else she got wrong. She resolves to change her ways (“I decided I needed a complete makeover, except this time, I’d make over my soul”) by first arranging a Pismo Beach disaster charity drive (one of Heckerling’s subtlest jokes), and then helping Tai find love with Travis. Eventually, Cher considers Josh (Paul Rudd)—her older ex-stepbrother from college, who’s interested in social responsibility, black clothes, Radiohead, and poolside Nietzsche—and realizes she’s in love. And what’s more, she has loved Josh all along. Their playfully mocking dynamic throughout the film recalls the classic love-hate relationship of Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night (1932). He calls out her spoiled behavior (“Who watching the galleria?”), and she insults his pretensions. But their mutual affection somehow works as romantic chemistry.

As mentioned, Clueless is a variation on Jane Austen’s Emma, published in 1815, just two years before the author’s death. Though it’s not a direct adaptation that redresses the original scenario in a Beverly Hills milieu, its spirit captures Austen’s commentary on the depthless rituals and vacuous concerns of women in Victorian-era England. The young women in Austen’s book dismiss literary pursuits in favor of attending polite social gatherings at elaborate country houses, and they debate the finer points of appropriate attire for such functions. Austen used irony to portray and critique characters absorbed with cultural output, not to increase their knowledge or appreciate artistic expressions but to make themselves desirable prospects for marriage—the primary concern of women in her society. Similarly, Heckerling pokes fun at the rich by depicting Cher and her friends as spoiled and obsessed with status and boys, whereas caring about the world or turning in good schoolwork remain afterthoughts. Even Mel praises Cher for her ability to talk her way into better grades with her teachers (“Honey, I couldn’t be happier than if they were based on real grades”). The themes transcend their respective periods. As scholar Anna Despotopoulou observes, the young women in both Heckerling and Austen’s worlds adopt the fashions and class signifiers to appear “marketable” to boys or future husbands, yet their authors simultaneously critique and sentimentalize these motivations in relation to their characters’ self-awareness.

Moviegoers unfamiliar with Austen’s literary work in 1995 would soon learn that her protagonists often become fully self-aware late in the proceedings, only to fall in love with the least likely suitor. Clueless was the first of many Austen adaptations to appear on screens in 1995, marking a new resurgence of the author’s popularity onscreen. Heckerling’s film debuted in theaters over the summer, on July 19, followed by several book-to-film translations in the months to come. An adaptation of Persuasion debuted in England on BBC Two in April, and Sony Pictures Classics thought so much of Roger Michell’s film, starring Amanda Root and Ciarán Hinds, that the studio put it in U.S. theaters that September. Also in September, BBC One released their six-episode miniseries of Pride and Prejudice, featuring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth, which remains the book’s most faithful and celebrated adaptation for many Austenites. Similarly, Ang Lee’s film of Sense and Sensibility, adapted for the screen by Emma Thompson, who won an Oscar for her screenplay, arrived in theaters that December, boasting a cast that included Thompson, Alan Rickman, Hugh Grant, and Kate Winslet. In each case, Austen’s text received its best translation to screen before or since, and all were released within a few months of each other. Yet, while Heckerling’s treatment of Emma may be the loosest adaptation—more aptly described as “inspired by” than “adapted from”—it penetrated the pop-culture lexicon deeper than either the 1996 or 2020 adaptations of Emma starring Gwyneth Paltrow and Anya Taylor-Joy.

Clueless would not be what it is without Heckerling. A consummate New Yorker, Heckerling spent her youth absorbing classic cinema at the Museum of Modern Art and dreaming about directing films. She went on to study filmmaking at NYU and the American Film Institute in Los Angeles before landing her first directing gig on Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Based on the book by Cameron Crowe, who went undercover to write about what really goes on at high schools, Fast Times is often assessed as a typical teen comedy. But Heckerling fought to preserve the story’s interest in the internal lives of teenagers, particularly young women: their awkward courtship and first-time sexual experiences, and even a visit to an abortion clinic went further than most subsequent teen comedies would dare go. Heckerling’s career continued with a string of commercial hits, among them Johnny Dangerously (1984), National Lampoon’s European Vacation (1985), and the first two Look Who’s Talking comedies (1989, 1990). Clueless was seeded when Twentieth Century Fox hired Heckerling to develop a high-school sitcom. With a story in mind, she soon realized that it recalled Emma. So she revisited the book and, enthralled by Austen’s arc for the character, resolved to draw more directly from the source material, calling her series I Was a Teenage Teenager. Heckerling’s series, which featured Cher, Dionne, and several other characters who would eventually appear in Clueless, evolved into a feature film project at Fox before the studio put Heckerling’s script into turnaround.

Clueless would not be what it is without Heckerling. A consummate New Yorker, Heckerling spent her youth absorbing classic cinema at the Museum of Modern Art and dreaming about directing films. She went on to study filmmaking at NYU and the American Film Institute in Los Angeles before landing her first directing gig on Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Based on the book by Cameron Crowe, who went undercover to write about what really goes on at high schools, Fast Times is often assessed as a typical teen comedy. But Heckerling fought to preserve the story’s interest in the internal lives of teenagers, particularly young women: their awkward courtship and first-time sexual experiences, and even a visit to an abortion clinic went further than most subsequent teen comedies would dare go. Heckerling’s career continued with a string of commercial hits, among them Johnny Dangerously (1984), National Lampoon’s European Vacation (1985), and the first two Look Who’s Talking comedies (1989, 1990). Clueless was seeded when Twentieth Century Fox hired Heckerling to develop a high-school sitcom. With a story in mind, she soon realized that it recalled Emma. So she revisited the book and, enthralled by Austen’s arc for the character, resolved to draw more directly from the source material, calling her series I Was a Teenage Teenager. Heckerling’s series, which featured Cher, Dionne, and several other characters who would eventually appear in Clueless, evolved into a feature film project at Fox before the studio put Heckerling’s script into turnaround.

Even though Heckerling had a proven track record for moneymakers, Hollywood sexism and its lack of faith in women directors framed her as a risk to the studio. Many executives questioned her script’s focus on girls over boys—since boys were the subject of most teen movies to this point—and further, made an issue out of the ex-step-sibling love story. In Jen Chaney’s oral history of Clueless, Heckerling explains that her screenplay’s romance between Cher and Josh stems from a common practice in the Russian-Jewish ghettos in the Pale of Settlement. Her grandparents, step-siblings with no blood relations, and both single after a spousal death, married out of necessity to survive and remained together for decades. In the film, Heckerling softens the relationship even further when Cher dismisses her familial relationship to Josh by telling her father: “You were hardly even married to his mother, and that was five years ago.” Regardless of Hollywood’s protests over these thin familial connections, producer Scott Rudin soon backed the project. Rudin’s confidence in Heckerling’s script launched a bidding war among several Hollywood studios. Paramount Pictures won, later using its business ties with MTV, another entity owned by Viacom, to market the film to the target youth demographic. With a budget of $13 million, Heckerling assembled a cast of unknowns—many of them having auditioned for the TV show version at Fox—and, alongside cinematographer Bill Pope, shot on locations around Beverly Hills and Occidental College in Los Angeles.

For Heckerling, Alicia Silverstone was the only option for Cher when Clueless was still a TV show planned for Fox. If you were watching MTV in the early 1990s, it was difficult to miss Silverstone. Besides some television work, including a guest appearance on The Wonder Years and a couple of TV movies, her memorable appearance in the Aerosmith music video “Cryin’” and later “Amazing” and “Crazy” made everyone wonder, “Who is that?” At the same time, casting director Carrie Frazier discovered her by way of The Crush (1993), Silverstone’s first big-screen feature as a teen who develops a dangerous fixation on Cary Elwes. MTV gave Silverstone a statue for the Best Breakthrough Performance in The Crush at the 1994 MTV Movie Awards, ensuring she was someone to watch. Heckerling and Frazier both settled on the 17-year-old after a single screen test, and it’s easy to understand why. Silverstone has a natural charm and presence, perfectly suited for Cher. The other teen characters were assembled from actors whose auditions came both before and after Clueless was a television show, many of them getting their big break as a result. Donald Faison, Brittany Murphy, Breckin Meyer, and Jeremy Sisto each had a few small roles on their resumes, but Clueless made them recognizable faces. Stacey Dash had the most credits to her name, including ‘Mo Money (1992) and Renaissance Man (1994). Heckerling’s comedy also marked the first time audiences were introduced to Paul Rudd, who had already completed work on another film, Halloween 6: The Curse of Michael Myers; however, the beleaguered horror sequel wouldn’t hit theaters until the fall of 1995, after Clueless.

From the first images of Clueless, Heckerling makes her satirical lens known. A series of zooms and youthfully exuberant angles set against The Muffs’ “Kids in America” frame the students of Bronson Alcott High School. “Okay, so you’re probably going, ‘Is this like a Noxzema commercial or what?’” Cher remarks in her ever-present narration. Indeed, the equally stunning and ridiculous costumes, rooted in high couture and inventive designs, would set trends for much of the decade. Heckerling and costume designer Mona May worked together to develop the teens’ distinctive look, which coopted the prevalent gunge style popular at the time, heavy in plaids and baggy pants, and elevated the look into “high-meets-low” designs. Cher’s various plaid outfits with knee-high socks and Dionne’s series of ornate hats proved both amusing and trendsetting. Department store buyers didn’t have Clueless on their radar prior to its release, but the film’s clothing inspired many teens to search for the film’s style in their local shops that, initially anyway, had nothing to offer those wannabe Chers. And while the fashion on display in the film was meant to be over-the-top, Heckerling never belittles Cher for her interests. Rather, it acknowledges that there’s an artistry and personal expression involved in fashion, and Cher has mastered the artform—to a fault, given that it preoccupies her mind and distracts her from what she’s feeling. In this sense, Hecklering’s use of fashion is both a comic exaggeration and a thoughtful component of Cher’s character.

From the first images of Clueless, Heckerling makes her satirical lens known. A series of zooms and youthfully exuberant angles set against The Muffs’ “Kids in America” frame the students of Bronson Alcott High School. “Okay, so you’re probably going, ‘Is this like a Noxzema commercial or what?’” Cher remarks in her ever-present narration. Indeed, the equally stunning and ridiculous costumes, rooted in high couture and inventive designs, would set trends for much of the decade. Heckerling and costume designer Mona May worked together to develop the teens’ distinctive look, which coopted the prevalent gunge style popular at the time, heavy in plaids and baggy pants, and elevated the look into “high-meets-low” designs. Cher’s various plaid outfits with knee-high socks and Dionne’s series of ornate hats proved both amusing and trendsetting. Department store buyers didn’t have Clueless on their radar prior to its release, but the film’s clothing inspired many teens to search for the film’s style in their local shops that, initially anyway, had nothing to offer those wannabe Chers. And while the fashion on display in the film was meant to be over-the-top, Heckerling never belittles Cher for her interests. Rather, it acknowledges that there’s an artistry and personal expression involved in fashion, and Cher has mastered the artform—to a fault, given that it preoccupies her mind and distracts her from what she’s feeling. In this sense, Hecklering’s use of fashion is both a comic exaggeration and a thoughtful component of Cher’s character.

Similarly, Heckerling and Pope adopt an MTV aesthetic, or perhaps MTV adopted the film’s aesthetic. The images in Clueless are bright and optimistic, and Pope’s credits in genre pictures over several collaborations with Sam Raimi (Darkman, 1990; Spider-Man 2, 2004), the Wachowskis (The Matrix Trilogy, 1999 and 2003), and Edgar Wright (Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, 2011; The World’s End, 2013) do not suggest he could or would make a film like this. But he brings a subtle style to the images, which implies the film takes place just outside of reality. “The word is happy,” Heckerling told Pope. “I want this thing to be happy. I don’t want any sadness. I want complete happiness throughout this whole movie.” Such buoyancy presents a contrast to the reality of other high school movies of the decade, which often dwelled on the conflict between teachers and students. See Dangerous Minds (1995), released a month after Clueless, or The Substitute (1996)—both about adults clashing with a violent youth element in classrooms. Additionally, Clueless follows in the line of high school movies set in Los Angeles during the ‘90s, including Encino Man and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, both in 1992, although both blend a fantastical element into a teen setting. But by the time Clueless hit theaters, the Hughesian era of teen comedies and romances had petered out, and Heckerling’s film would usher in a new wave.

The language of Clueless is also famously and comically arch, catchy, and absurd, outside of the customary “likes” and “totallys” stereotypical of the California girl identity. To research how students behaved and spoke, Heckerling observed classes at a Beverly Hills high school, copying some of the common phrases and including them in her script. Other sayings originated from a jive-talk dictionary Heckerling had since the ‘70s, a UCLA slang study, and Heckerling’s imagination. Some expressions, such as “Whatever” with the accompanying hand gesture, were omnipresent. And Cher’s famous “as if” line had already been popularized years earlier by Mike Myers’ “Wayne’s World” sketch on Saturday Night Live (“Shyeah, as if!”). The script is also chock full of contemporary pop-culture references, occupying the post-Tarantino tendency for discussions of media within media. References to Cindy Crawford, Marky Mark, Mentos commercials, Kato Kaelin, and Luke Perry may not have much meaning to younger millennial and Gen-Z viewers, nor would describing an attractive male as a “Baldwin,” given the current status of the famous brothers. But Cher calling her mother a “Betty,” a reference to The Flintstones, might be a more permanent cultural touchstone. Still, if some of the references are lost on some viewers, Heckerling writes Cher’s hilariously stupid-but-smart dialogue. Cher’s early film speech—where Silverstone actually messed up the pronunciation of Haitians to “Hate-ee-ans,” much to Heckerling’s delight—sounds inane but manages to have a humanist view of immigration policy from which politicians today could learn a thing or two:

“So, okay. Like right now, for example, the Haitians need to come to America. But some people are all, ‘What about the strain on our resources?’ But it’s like, when I had this garden party for my father’s birthday, right? I said RSVP because it was a sit-down dinner. But people came that, like, did not RSVP. So I was, like, totally buggin’. I had to haul ass to the kitchen, redistribute the food, squish in extra place settings. But by the end of the day, it was, like, the more, the merrier. And so if the government could just get to the kitchen, rearrange some things, we could certainly party with the Haitians. And in conclusion, may I please remind you that it does not say ‘RSVP’ on the Statue of Liberty.”

What at first seems like the ill-prepared speech by someone who didn’t do her homework ultimately reveals itself to have a perspective. That’s the charm of Cher, who may seem obsessed with surfaces and shallow concerns such as shopping and brand names, but beneath her exterior, there’s a young woman whose interest in fashion, matchmaking, and charity suggests her creativity and generosity. But these tendencies are hindered by her obliviousness to a world outside of her Beverly Hills existence (Why learn topark when “everywhere you go has valet”?). Fortunately, Josh prompts Cher to check her privilege—evidenced during Cher’s worst offense when she tells their housekeeper Lucy (Aida Linares) from El Salvador that she “doesn’t speak Mexican,” to which Josh responds by tearing into Cher’s narrow worldview. Elsewhere, Cher seeks empowerment where she can find it, such as wielding fashion as a system of control. As Dionne notes, “Cher’s main thrill in life is a makeover. It gives her a sense of control in a world full of chaos.” She doesn’t know anything else. Chaney notes that Cher’s lack of perspective “often goes hand in hand with being white and wealthy,” thus making Clueless still relevant in today’s somewhat more socially conscious culture. Following the trajectory of Emma, Heckerling writes Cher to reflect on her well-meaning but unaware behavior and no longer think of people such as Tai as a “project.” Ultimately, Cher accepts that she cannot control the world, but she can control herself through personal growth.

What at first seems like the ill-prepared speech by someone who didn’t do her homework ultimately reveals itself to have a perspective. That’s the charm of Cher, who may seem obsessed with surfaces and shallow concerns such as shopping and brand names, but beneath her exterior, there’s a young woman whose interest in fashion, matchmaking, and charity suggests her creativity and generosity. But these tendencies are hindered by her obliviousness to a world outside of her Beverly Hills existence (Why learn topark when “everywhere you go has valet”?). Fortunately, Josh prompts Cher to check her privilege—evidenced during Cher’s worst offense when she tells their housekeeper Lucy (Aida Linares) from El Salvador that she “doesn’t speak Mexican,” to which Josh responds by tearing into Cher’s narrow worldview. Elsewhere, Cher seeks empowerment where she can find it, such as wielding fashion as a system of control. As Dionne notes, “Cher’s main thrill in life is a makeover. It gives her a sense of control in a world full of chaos.” She doesn’t know anything else. Chaney notes that Cher’s lack of perspective “often goes hand in hand with being white and wealthy,” thus making Clueless still relevant in today’s somewhat more socially conscious culture. Following the trajectory of Emma, Heckerling writes Cher to reflect on her well-meaning but unaware behavior and no longer think of people such as Tai as a “project.” Ultimately, Cher accepts that she cannot control the world, but she can control herself through personal growth.

Setting aside its glimmering surface, lighthearted romance, and attractive stars, Clueless arrived at a moment that began to distinguish between the second and third waves of feminism. Generally speaking, second-wave feminists redistributed the traditional social designations for women starting in the 1960s, rejecting female gender roles and sexual stereotypes in favor of legal equality, social justice, and more agency. This era of feminism would have looked upon Cher and company as frivolous and demeaning representations of women who are overly concerned with superficial matters such as fashion and boys. They would, and in some cases did, question the extent to which style and sexual liberation reinforce older regimes of oppression. But with the arrival of third-wave feminism among Gen-Xers, a newfound celebration of “Girl Power” and sex positivity granted women ownership and freedom over their sexuality, using aspects of style and sex as empowering. In the age of Madonna and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Cher could be a feminist while being blonde with a good fashion sense. This is encapsulated in one of the film’s most iconic moments when Cher demonstrates her power. While making her way to school in the courtyard and proudly displaying her yellow plaid outfit, Cher fends off an unwanted advance by shoving a boy aside and declaring, “Ugh, as if!” Third-wave feminism allowed for such pluralistic definitions of women, distinguished by its inclusion of a myriad of identities, regardless of class, ethnicity, or even gender. Moreover, its women could celebrate the fun aspects of girldom. As philosophy professor Dr. Susan Hopkins notes, they “put the feminine back into philosophy” by celebrating the Nietzschean view of women who use gender performativity as their power—seen in the fashion, language, and downright Cher-ness of Clueless

Teen movie romances and comedies to this point were not known for their progressiveness and inclusion, nor did they make young women feel empowered to embrace their individuality. But Heckerling imagines a universe where the usual discriminatory lines of class, race, gender, and sexuality become almost non-issues. In Clueless, the posh white girl could be best friends with a Black girl without calling out the fact; the reveal of a gay character isn’t a matter of controversy, and he’s accepted without question once he’s out. Instead, everyone feels empowered to be themselves, and no one becomes a target. The effect is, as Heckerling wanted, “happy.” Clueless is absent of mean girls or villains. The closest antagonist offered is Amber (Elisa Donovan), whose insulting back-and-forth with Cher about their wardrobe choices hardly represents an opposition. And Elton’s unrequited affection for Cher makes for an ugly scene. Moreover, the comical portrait of Cher as an airhead or social butterfly isn’t simply poking fun at her; regardless of Cher’s sometimes problematical behavior that reflects her privilege, the film is refreshingly free of judgment. In an era when the entitlement of rich white women has been rightly questioned, Cher is someone who learns to accept difference and make amends for her bad behavior, such as apologizing to Lucy or encouraging Tai to pursue Travis after the misguided attempt to pair her with Elton. And in the end, she will probably continue to embrace her fashion sense and live in Beverly Hills, but perhaps with more self-awareness in the future.

When Clueless opened in the summer of 1995, Batman Forever and Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 dominated the summer box office. Still, MTV promoted Clueless nonstop, and droves of teens scrambled into theaters to make the $13 million production into a sleeper hit. Even critics received it with surprising praise, among them Roger Ebert, who anticipated its universal appeal. “The movie is aimed at teenagers,” Ebert wrote, “but like all good comedies, it will appeal to anyone who has a sense of humor and an ear for the ironic.” Its success would inspire a resurgence of teen rom-coms and dramas, especially those based on classical literature: 10 Things I Hate About You (1999) from Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew; She’s All That (1999) from George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion; Cruel Intentions (1999) from Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Dangerous Liaisons; O (2001) from Shakespeare’s Othello; Easy A (2010) from Nathaniel Hawthorn’s The Scarlet Letter. The examples could go on. And while recent appreciations in Vogue and other publications have called the film a “cult classic” and noted its return to the pop-culture lexicon due to the recent wave of ‘90s nostalgia, Clueless has never really gone away. Since 1995, several generations of teens and adults have continued to celebrate its humor and message, suggesting it’s not so much a “cult” as a just-plain-classic film.

When Clueless opened in the summer of 1995, Batman Forever and Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 dominated the summer box office. Still, MTV promoted Clueless nonstop, and droves of teens scrambled into theaters to make the $13 million production into a sleeper hit. Even critics received it with surprising praise, among them Roger Ebert, who anticipated its universal appeal. “The movie is aimed at teenagers,” Ebert wrote, “but like all good comedies, it will appeal to anyone who has a sense of humor and an ear for the ironic.” Its success would inspire a resurgence of teen rom-coms and dramas, especially those based on classical literature: 10 Things I Hate About You (1999) from Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew; She’s All That (1999) from George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion; Cruel Intentions (1999) from Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Dangerous Liaisons; O (2001) from Shakespeare’s Othello; Easy A (2010) from Nathaniel Hawthorn’s The Scarlet Letter. The examples could go on. And while recent appreciations in Vogue and other publications have called the film a “cult classic” and noted its return to the pop-culture lexicon due to the recent wave of ‘90s nostalgia, Clueless has never really gone away. Since 1995, several generations of teens and adults have continued to celebrate its humor and message, suggesting it’s not so much a “cult” as a just-plain-classic film.

Heckerling captures the privilege of being white and wealthy in Clueless, and she makes a potentially intolerable character endearing by showing how out of touch she can be. While Cher’s titular quality remains a source of humor and surprising humanity, the character can feel troublesome at times. Should we be rooting for someone like Cher? Ultimately, Heckerling’s willingness to poke fun at and question Cher’s sheltered worldview, and then compel her to grow beyond her evident limitations, is what makes her an endearing character. Without the director’s delicate formula of critique and earnestness, irony and sentimentality, Cher might be intolerable. Of course, Heckerling had a terrific template in Austen’s 200-year-old book and makes the material feel fresh, not only in 1995 but also today. Just as Austen’s perspective continues to feel timeless in its ironic depiction of the upper class, Clueless features a wry portrait of a self-involved person who stops thinking about herself and quits telling everyone else how to live according to her ideology. What a notion. For all of its glitzy clothes, endlessly quotable dialogue, and pop-culture references, the film’s quick-witted high school satire and heartwarming romance are contained within a greater story about Cher trying to be a better person. For that, Clueless is a perennial classic.

(Note: This essay was commissioned and posted to Patreon on September 27, 2022. Thank you for your contributions and support, Brenda!)

Bibliography:

Chaney, Jen. The Oral History of “Clueless” as Told by Amy Heckerling and the Cast and Crew. Gallery Books, 2015.

—. “Clueless Is a Great Teen Movie. It’s Also a Satire About the White and Wealthy.” Vulture, 8 July 2020. https://www.vulture.com/article/clueless-is-a-great-teen-movie-its-also-a-satire.html. Accessed 1 September 2022.

Despotopoulou, Anna. “Girls on Film: Postmodern Renderings of Jane Austen and Henry James.” The Yearbook of English Studies, vol. 36, no. 1, 2006, pp. 115–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3508740. Accessed 1 September 2022.

Galperin, William. “Adapting Jane Austen: The Surprising Fidelity of ‘Clueless.’” The Wordsworth Circle, vol. 42, no. 3, 2011, pp. 187–93. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24043146. Accessed 1 September 2022.

Hopkins, Susan. “Isn’t Clueless about Feminism’s Nietzsche.” Philosophy Now, issue 109. Dec 2015/Jan 2016.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review