The Definitives

Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

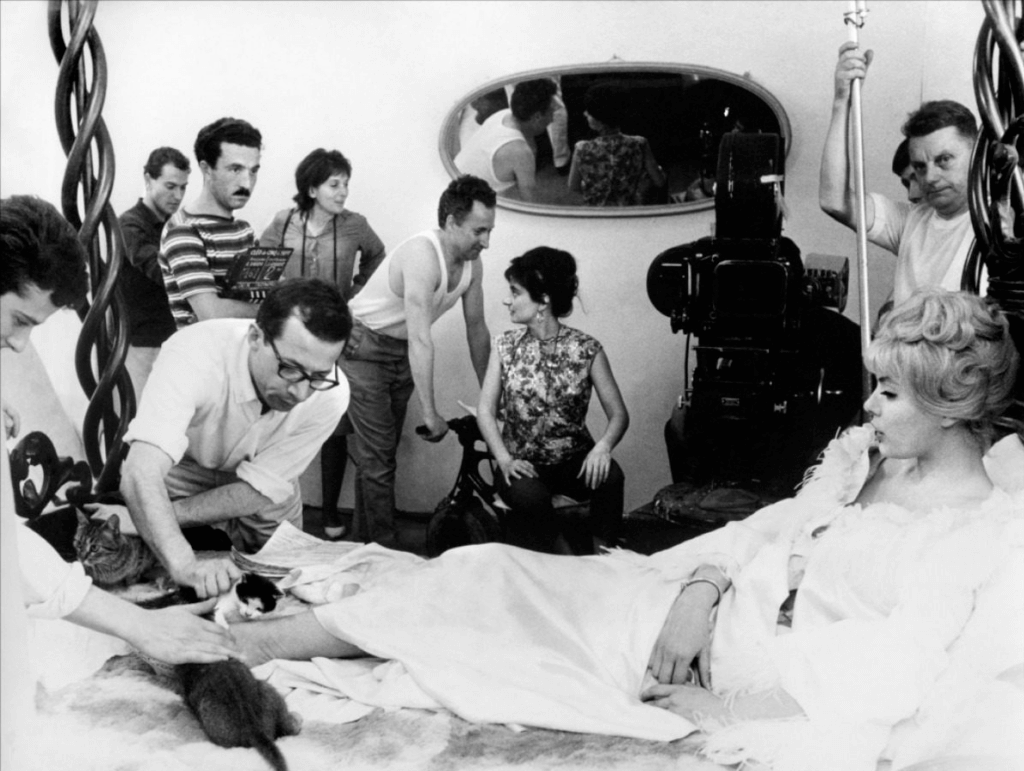

Cléo from 5 to 7 (Cléo de 5 à 7), often the first film mentioned in association with its writer-director, Agnès Varda, occupies the internal and external worlds of a woman who awaits test results. She fears the outcome will be cancer, and so the ensuing 90 minutes, captured in what has been inaccurately described as real-time, inhabits both subjective and objective time. Marrying observation with poetic expression, Varda conveys seemingly inconsequential passages in Cléo’s life and builds them into a multifaceted portrait. While Varda’s sense of realism captures many convincing details—from actual Parisian streets to rogue cats—Cléo’s view of herself is distorted, shaped by how others perceive her, making the character’s mirror image a reflector not of herself but of her objectification. Although Varda and her work on Cléo from 5 to 7 have been described in relation to the French New Wave (nouvelle vague), she defies characterization. A true original, her inspiration and motivations conform only to her creative instincts, not in opposition to existing styles or upholding a particular school of filmmaking. Rather, from a place of fearless independence, Varda’s film investigates the nature of female identity with a series of thematic and formal contradictions. Through her character’s relationship with beauty, mirrors, death, and public spaces, Varda shows Cléo alternating between coquettishness and internal anxiety until she finds strength from within, to diagnose the cancer that threatens contemporary individuals.

Set between the hours of 5 p.m. and 6:30 p.m. on June 21, 1961, the film follows the titular aspiring pop singer played by Corinne Marchand. Facing a potential mortal diagnosis, she visits a tarot card reader during the opening credits scene. The angle looks down at the cards, which appear in color, but every other scene—shot by Claude Chabrol’s regular cinematographer Jean Rabier—appears in black and white. From the outset, Varda confronts the audience with the contrast of color and monochrome, alternating between them to capture Cléo’s reaction to the reading and instilling a conflict that will emerge in visual and narrative terms throughout the film. The fortune-teller pulls a death card, where a grim skeletal figure appears in opposition to the beautiful maiden that represents Cléo. The fortune teller reassures her client that it indicates “a complete transformation of your whole being,” which doesn’t necessarily mean literal death. Even so, when Cléo leaves her reading, the fortune teller remarks to her husband in the next room: “She’s doomed.” The sequence leaves much to interpretation, from Varda’s use of color to the meaning of the tarot cards. In these allegorical terms, Varda remarks that anything is possible, whereas the world shown in black-and-white imagery takes on a narrow reality aligned with Cléo’s subjectivity.

To be sure, Cléo experiences a heightened awareness of time and her presence in her surroundings. After her reading, she regards her image in the mirror, reassuring herself, “As long as I’m beautiful, I’m alive and ten times more so than others.” However, looking in the mirror only confirms what others see, conforming to the notion that a woman’s value and identity reside in her beauty. Varda stages the moment similarly to one in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), where Charles Foster Kane, alone in his Xanadu palace, passes by a mirror that hangs opposite another, creating a repeated reflection that appears to go on forever, symbolizing his fractured identity over which he no longer has control. Similarly, in Cléo from 5 to 7, the mirrored image signals Cléo’s obsession with her beauty, leaving her identity rooted in visual excess. The mirroring occurs countless times until her image disappears into the distance, a powerful symbol of how Cléo’s identity often registers as meaningless next to how she is perceived on the surface alone. She turns her head admiringly, yet she’s unable to escape the dark shadow that rests across the left side of her face. The lighting isn’t perfect, suggesting that the mirror doesn’t supply her with the validation she needs after her reading.

To be sure, Cléo experiences a heightened awareness of time and her presence in her surroundings. After her reading, she regards her image in the mirror, reassuring herself, “As long as I’m beautiful, I’m alive and ten times more so than others.” However, looking in the mirror only confirms what others see, conforming to the notion that a woman’s value and identity reside in her beauty. Varda stages the moment similarly to one in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), where Charles Foster Kane, alone in his Xanadu palace, passes by a mirror that hangs opposite another, creating a repeated reflection that appears to go on forever, symbolizing his fractured identity over which he no longer has control. Similarly, in Cléo from 5 to 7, the mirrored image signals Cléo’s obsession with her beauty, leaving her identity rooted in visual excess. The mirroring occurs countless times until her image disappears into the distance, a powerful symbol of how Cléo’s identity often registers as meaningless next to how she is perceived on the surface alone. She turns her head admiringly, yet she’s unable to escape the dark shadow that rests across the left side of her face. The lighting isn’t perfect, suggesting that the mirror doesn’t supply her with the validation she needs after her reading.

Waiting for the results of her medical exam, Cléo walks down a Montparnasse boulevard and becomes a flâneuse of Paris, who, rather than strolling in the Baudellairian sense of the flâneur as a man who participates in the crowd, she is ogled by salespeople, enamored men, and pedestrians. She stops at a café to meet her assistant, Angèle (Dominique Davray). In a booth, her image fractures in the seam between mirrors, inciting panic in Cléo and reminding her of what may come. While Angèle tries to calm her with a story, Cléo overhears the conversation between two would-be lovers—a man trying to pressure a woman to have sex at their next rendezvous, which she refuses. Later in the film, in a different café, Cléo hears a similar conversation when a man scorns a woman: “You think I have all day to wait for you?” Cléo lives in a world where men thrust their expectations and demands on women, where women’s identities are shaped by patriarchal concepts of beauty and desire. Note how, after breaking down in Angèle’s presence, Cléo restores her composure in a hat shop, where trying on fashionable headwear and regarding herself in a mirror proves restorative. “I get giddy just trying on hats and dresses,” she remarks, admiring her well-lit image in the store mirrors. But later in a taxi ride, Cléo sees a display of masks, a reminder that her identity is false, and the sight prompts a bout of nausea.

After the color prologue, Varda arranges the film within thirteen chapters, each with a title denoting the subject and timeframe to be covered (for example, “Chapter 1: Cléo from 5.05 to 5.08”). Most of them concern Cléo, but others sometimes detour into side characters or random Parisians (“Chapter VIII: Some others from 5.45 to 5.52”), with no consistency between the chapters and how much time is devoted to its respective subject. Moreover, Varda further segments life into temporality by saturating every scene with objects that trace time: clocks, taxi meters, metronomes, and schedules measure out the temporal pieces of Cléo’s life. The devices have been carefully integrated into each scene without overemphasis, providing visual or aural evidence of Varda’s real-time conceit. If not seen on camera, the sound of a ticking clock might be heard, as in the prologue with the fortune teller, and we hear the presence of a clock halfway through the scene. But these structural devices do not represent objectivity or real-time filmmaking. Take when Cléo descends the stairs after her tarot card reading, and Varda repeats a moment of Cléo three times for emphasis—a poetic flourish that stands in the face of any claim to the film’s objectivity.

Although Varda is most commonly associated with cinema, her career started in photography and extended into performance pieces, gallery collections, and multimedia installations later in her career. Varda’s background sets her apart from her contemporaries and distinguishes Cléo from 5 to 7, since her photographer’s interest in detail and composition adds complexity to her portrayal of the world and its inhabitants. Even so, Varda has been lumped in with the French New Wave filmmakers of the 1960s—a crowd including Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Éric Rohmer, sometimes known as the Right Bank Group for their location in Paris—and is often called “the Mother of the New Wave” by scholars. Others associate her with the Left Bank Group, a politically minded and geographically isolated group of filmmakers, such as Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. Such links are made perhaps because these movements and their filmmakers proved to be so influential to world cinema, and so it’s tempting to contain Varda within their boundaries. However, her films should be distinguished from those of her male contemporaries; they instill a critical female perspective that questions and confronts patriarchal norms, particularly regarding the gaze. As scholar Steven Ungar notes, she was “a female film author (auteure) before the concept of film authorship emerged.”

Although Varda is most commonly associated with cinema, her career started in photography and extended into performance pieces, gallery collections, and multimedia installations later in her career. Varda’s background sets her apart from her contemporaries and distinguishes Cléo from 5 to 7, since her photographer’s interest in detail and composition adds complexity to her portrayal of the world and its inhabitants. Even so, Varda has been lumped in with the French New Wave filmmakers of the 1960s—a crowd including Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Éric Rohmer, sometimes known as the Right Bank Group for their location in Paris—and is often called “the Mother of the New Wave” by scholars. Others associate her with the Left Bank Group, a politically minded and geographically isolated group of filmmakers, such as Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. Such links are made perhaps because these movements and their filmmakers proved to be so influential to world cinema, and so it’s tempting to contain Varda within their boundaries. However, her films should be distinguished from those of her male contemporaries; they instill a critical female perspective that questions and confronts patriarchal norms, particularly regarding the gaze. As scholar Steven Ungar notes, she was “a female film author (auteure) before the concept of film authorship emerged.”

However inapt, the New Wave association is not without some merit. Film scholars and critics often list Varda’s debut film, La Pointe Courte (1955), as a forerunner to the movement that started a few years later. But Varda claims she had only seen about 25 films or more when she started making her debut, so her knowledge of camera technique derives from photography and art history, as opposed to cinema. By contrast, Truffaut and Godard sought to use on-location shooting, a screenplay written by an auteur, and untrained actors to create a sense of authenticity, establishing a platform against the historical “Tradition of Quality” of studio-bound filmmaking. Their contributions to the medium engaged in a film historical conversation, decrying the traditional techniques they, as critics for the Cahiers du Cinéma, saw overused by the French film industry. Made around the same time but before Truffaut’s (The 400 Blows, 1959) and Godard’s (Breathless, 1960) respective debuts, many scenes in Cléo from 5 to 7 seem to align with the New Wave agenda, taking place in Parisian locations and supplying a view of the city through Cléo’s eyes, thus Varda’s camera. On the surface, it looks as though Varda intends to make the same arguments as Truffaut and Godard. However, as Ungar observes, Varda’s lifelong interest in observational photography, modern art, and fashion inspired her creative decisions in La Pointe Courte and Cléo from 5 to 7, which alternate between documentary realism and theatrical staging.

Some background on Varda may better differentiate her from New Wave filmmakers. Born Arlette Varda in 1928 in Ixelles, Belgium, she was the daughter of a Greek father and a French mother. She later took the name Agnès as a teenager after learning it was a common name among women on her father’s side. In 1940, her family moved to Sète, France, where she spent her teen years. When she was 18, Varda moved to Paris to study, attending Lycée Victor Duruy before the Sorbonne, where she earned a degree in literature and psychology. By 1948, she went on to study art history at the École du Louvre and later photography at the École des Beaux-Arts. After her formal education, Varda worked as a photographer at the Théâtre National Populaire for several years, where she did more than take pictures; she also contributed to rehearsals and publicity, honing her craft for aesthetics over literary-minded pursuits by working within creative, collaborative environments. There, she met Silvia Monfort and Philippe Noiret, who starred in La Pointe Courte, which she started shooting in 1954. About a married couple in the title’s small fishing village, the film shows Varda’s interest in expressive compositions and real-life subjects—a quality of her work honed in her freelance photojournalism for Marie-Claire, Prestige-France, and Réalités. Her interest in photography, along with its potential for visual experimentation, lasted throughout her career. Even her final documentary about her life, Varda by Agnès (2019), reveals her tendency to stage tableau-like installations to capture a slice of the real.

Instead of a director taking part in a movement against conventional filmmaking like her New Wave contemporaries, Varda was an original, even among originals. Writing in Le Parisien libéré about La Pointe Courte, preeminent critic and co-founder of Cahiers du Cinéma, André Bazin, called Varda’s film “free and pure” and praised her independence. She had made her debut for considerably less than either Truffaut’s or Godard’s debuts, relying on personal loans, an inheritance, and contributions from the cast and crew that took more than a decade to repay. Similarly, making Cléo from 5 to 7 required Varda, an untrained filmmaker, to apply for government approval before her truly independent production could be distributed in theaters. Varda did not set out to conform to the manifesto-like decrees followed by many New Wave directors; instead, she sought to bring photographic images to life through expressive movement and dialogue. Her choices conform more to the category of Left Bank filmmakers, reinforced by two directors from that group, Alain Resnais and Henri Colpi, who served as editors on La Pointe Courte for the then-untrained Varda. Nevertheless, Varda remained only vaguely associated with both groups and loyal to neither of them. This did not stop the Cahiers du Cinéma from claiming Varda as one of its own in the magazine’s December 1962 issue, which, as Ungar observes, included Varda on a list of filmmakers who made up “La Nouvelle Vague”—a list of 162 names that included only three women.

Instead of a director taking part in a movement against conventional filmmaking like her New Wave contemporaries, Varda was an original, even among originals. Writing in Le Parisien libéré about La Pointe Courte, preeminent critic and co-founder of Cahiers du Cinéma, André Bazin, called Varda’s film “free and pure” and praised her independence. She had made her debut for considerably less than either Truffaut’s or Godard’s debuts, relying on personal loans, an inheritance, and contributions from the cast and crew that took more than a decade to repay. Similarly, making Cléo from 5 to 7 required Varda, an untrained filmmaker, to apply for government approval before her truly independent production could be distributed in theaters. Varda did not set out to conform to the manifesto-like decrees followed by many New Wave directors; instead, she sought to bring photographic images to life through expressive movement and dialogue. Her choices conform more to the category of Left Bank filmmakers, reinforced by two directors from that group, Alain Resnais and Henri Colpi, who served as editors on La Pointe Courte for the then-untrained Varda. Nevertheless, Varda remained only vaguely associated with both groups and loyal to neither of them. This did not stop the Cahiers du Cinéma from claiming Varda as one of its own in the magazine’s December 1962 issue, which, as Ungar observes, included Varda on a list of filmmakers who made up “La Nouvelle Vague”—a list of 162 names that included only three women.

Those trying to categorize Varda often overlook that she started her own production and distribution company, Ciné-Tamaris, in 1954, located in the Rue Daguerre apartment where Varda lived since 1951—also the location of her neighborhood documentary, Daguerréotypes (1975). Cocinor, the company responsible for producing and distributing most New Wave titles made by the Right Bank Group, did not release her work. Rather, she remained fiercely independent. After her filmmaking career stalled following the release of La Pointe Courte, she was approached in 1957 by the French Office of Tourism to make a short film showing the Loire Valley region. The 22-minute documentary piece, Ô saisons, ô châteaux, played at the Film Festival of Tours in 1958, where she met Jacques Demy, who would become her lifelong partner, collaborator, and documentary subject until his death in 1990. Demy introduced Varda to Georges de Beauregard, who would produce Demy’s debut Lola (1961). Beauregard would go on to produce films by Godard, Chabrol, and Jean-Pierre Melville. He also agreed to produce Varda’s next film, Cléo from 5 to 7, which played at the Cannes Film Festival in 1962. After the film’s success, she and Demy married, and their careers launched simultaneously, with the two supporting each other’s work from behind the scenes.

Varda described her perspective as an artist to interviewer Andrea Meyer as a woman’s, rooted in “intuition” and “seeing” through a “stream of feelings.” Her work on Cléo from 5 to 7 involves a free-flowing interplay of vérité sequences and heightened emotional expressions. She did not believe in objectivity, even in her documentaries where she remains a regular presence either on or behind the camera, as if announcing their subjectivity. So while Cléo from 5 to 7 adopts a seemingly objective and regimented structural agenda and temporal framing device, these frameworks draw from Cléo’s subjectivity. For instance, after the café, Cléo and Angèle take a cab back to her apartment. The ride there unfolds in a long drive approximating real-time, shot on actual Paris streets, guerilla-style. Another sequence of continuity editing follows Cléo upstairs and inside her apartment, charting every step with a logical progression of shots. Extended sequences like these seem to be about recording life in real-time, whereas Varda’s interruptive and expressive uses of temporal and visual ellipses, repetitions, and compressions throughout reinforce that much of the film takes place in Cléo’s subjective perspective. Given this, Cléo from 5 to 7 could be mistaken as a film in which nothing happens. Much of the runtime involves Cléo traveling and killing time, and despite all the chapters and structures, the film is calibrated according to how Cléo experiences time. The regimentation of the chapters contrasts the feelings experienced within them, which distend and prolong moments, making them feel longer than the chapter header would suggest. Jump cuts gloss over certain moments, speeding them up, whereas edits in Cléo’s stroll down the streets of Paris compress time, so the overall effect shortens banal moments and extends others.

When Cléo returns home after her tarot card reading, she dolls herself up in white feathery frills and awaits her lover and manager, José (José-Luis de Vilallonga). Angèle warns her, “Not a word about your illness. Men hate that”—a line reinforcing Cléo’s perception that she must deny herself to appease men. But José leaves almost as soon as he arrives, barely taking notice of her beauty, thus leaving her empty again. When her music manager Bob (Michel Legrand) and lyricist Maurice (Serge Korber) arrive, they dismiss her anxiety about her test results (“She just wants attention”). Still, the sequence with Legrand, who provides the score to Cléo from 5 to 7, marks the most playful section in the film, complete with the camera swaying in tandem with the singers and the tempo of Legrand’s diegetic music. But the mood shifts when Bob and Maurice encourage Cléo to sing a new composition called “Without You,” where the lyrics speak of a lover who abandons the singer, who’s left “alone, pale, and ashen.” After her passionate performance of the song—where the setting goes black, isolating Marchand in the frame in a stylization that becomes more expressive as it goes—Cléo realizes that she wants to be more than a pretty object crafted by her managers and gazed upon by others. In a sudden outburst, Cléo breaks down and removes her ornate, twirly wig and leaves it hanging on a mirror. She heads out into the city, the wounded action acknowledging how her anxieties and fear of death have caused her to abandon any delusions and search for some truth in reality.

When Cléo returns home after her tarot card reading, she dolls herself up in white feathery frills and awaits her lover and manager, José (José-Luis de Vilallonga). Angèle warns her, “Not a word about your illness. Men hate that”—a line reinforcing Cléo’s perception that she must deny herself to appease men. But José leaves almost as soon as he arrives, barely taking notice of her beauty, thus leaving her empty again. When her music manager Bob (Michel Legrand) and lyricist Maurice (Serge Korber) arrive, they dismiss her anxiety about her test results (“She just wants attention”). Still, the sequence with Legrand, who provides the score to Cléo from 5 to 7, marks the most playful section in the film, complete with the camera swaying in tandem with the singers and the tempo of Legrand’s diegetic music. But the mood shifts when Bob and Maurice encourage Cléo to sing a new composition called “Without You,” where the lyrics speak of a lover who abandons the singer, who’s left “alone, pale, and ashen.” After her passionate performance of the song—where the setting goes black, isolating Marchand in the frame in a stylization that becomes more expressive as it goes—Cléo realizes that she wants to be more than a pretty object crafted by her managers and gazed upon by others. In a sudden outburst, Cléo breaks down and removes her ornate, twirly wig and leaves it hanging on a mirror. She heads out into the city, the wounded action acknowledging how her anxieties and fear of death have caused her to abandon any delusions and search for some truth in reality.

With that, Cléo sets out into the city once more, and Varda’s interest in her character’s role as a flâneuse returns to confront the protagonist with the reality of human physicality. Cléo sees street performers, one who swallows frogs, the other who pierces his bicep, and feels horrified at the grotesque physical sights. Seeking to restore herself after her deflating encounters with José and Bob, she wanders into a café, orders a cognac, and puts one of her songs on the jukebox, hoping for complements that do not come—only the gazing eyes of men. Then she visits her friend, Dorothée (Dorothée Blanck), who models nude for a sculpture class. Having been conditioned to see herself as an object for visual consumption by men, Cléo, ever self-conscious, could not imagine posing nude and having her flaws on display, later calling nudity “indecent.” But Dorothée has an alternative view: “My body makes me happy, not proud.” This registers as a foreign concept for Cléo, who sees ugliness as a fate worse than death. Afterward, Dorothée drives Cléo to a movie theater to visit Dorothée’s boyfriend Raoul (Raymond Cauchetier)—where they will watch a zippy, silent film-within-a-film—and the journey underscores Varda’s interest in the practical realities that eat away at time. Most filmmakers would cut away from long scenes of driving or walking in favor of dramatized time, but Varda uses what might be empty moments to heighten the tension from Cléo’s anxiety.

In the film’s final section, Cléo’s usual reflectors start to break, prompting her to look within herself. She drops a mirror outside of the movie theater and comes across a shattered shop window that can no longer show her reflection. So she wanders into Parc Montsouris, finding the park almost empty. In her solitude, she begins to feel whole. Soon she meets a soldier, Antoine (Antoine Bourseiller), who’s heading out that evening to fight in the Algerian War. Varda channels another source of contemporary anxiety with the inclusion of Antoine, an inevitable victim of the war who could have been shipping out to an anonymous conflict; instead, Varda’s references to the Algerian War confront a sociopolitical debate in France. Her inclusion of this ripped-from-the-headlines detail emphasizes the ongoing discussion about where colonialism fits within France’s progressive society—a conflict as potent as the contrast between beauty and death. Cléo and Antoine’s encounter is what Varda described to interviewer Michel Capdenac as “the meeting of two people at a moment of acute crisis.” They talk openly, unafraid to be their true selves. Antoine worries about “dying for nothing,” and Cléo about her potential disease, and both of them represent parallels for French identity at the time.

Shedding her final layer of artifice, Cléo admits to Antoine that her real name is Florence, and Cléo is her pop-star persona. In an effort to cheer her up, Antoine makes the connection that Flora was the goddess of Spring. But the association lands with an unintended grim note, since the date is June 21, 1961, which, on the astrological calendar, marks the beginning of Cancer, the Summer Solstice—the longest day of the year, what feels like an eternity for the protagonist. Spring has ended. Will cancer, an unintended homonym on Antoine’s part, also put an end to Cléo? Critics at the time questioned Varda’s use of cancer as manipulative, suggesting the film would have been just as effective without it. But cancer wasn’t merely a throwaway choice for Varda. She learned about cancer and its effects by visiting several cancer clinics and talking to over a hundred cancer patients, some newly diagnosed and others well into their trials. She sought to understand the anxiety and fear involved with facing a potentially fatal disease. Working with Marchand, for whom she wrote the part, the director recreated that anxiety in Cléo.

Shedding her final layer of artifice, Cléo admits to Antoine that her real name is Florence, and Cléo is her pop-star persona. In an effort to cheer her up, Antoine makes the connection that Flora was the goddess of Spring. But the association lands with an unintended grim note, since the date is June 21, 1961, which, on the astrological calendar, marks the beginning of Cancer, the Summer Solstice—the longest day of the year, what feels like an eternity for the protagonist. Spring has ended. Will cancer, an unintended homonym on Antoine’s part, also put an end to Cléo? Critics at the time questioned Varda’s use of cancer as manipulative, suggesting the film would have been just as effective without it. But cancer wasn’t merely a throwaway choice for Varda. She learned about cancer and its effects by visiting several cancer clinics and talking to over a hundred cancer patients, some newly diagnosed and others well into their trials. She sought to understand the anxiety and fear involved with facing a potentially fatal disease. Working with Marchand, for whom she wrote the part, the director recreated that anxiety in Cléo.

For Varda, cancer also served as a metaphor for how the city eats away at contemporary Parisians. The city is unkind to Cléo; its people gaze, objectify, and exploit. Varda sought to capture this aspect of Paris, contrasting its reputation as the romantic City of Lights. She extended her concept intertextually into Renaissance art. In a written statement about Cléo from 5 to 7 paired with an image of Hans Baldung Grien’s 1517 painting Death and the Maiden, Varda noted her “broad fear of the big city, of its dangers, and of losing oneself there alone.” The director compared her character’s preoccupation to a similar motif in Baldung Grien’s oil painting—and many others like it from the Renaissance—where a beautiful, Venus-like woman appears in the clutches of a skeleton or demon, representing death. Varda even went so far as to keep reproductions of the painting on display while shooting, to establish the haunted mood—that of death looming, along with the constant need to present a false front for visual consumption. The notion is further referenced by Antoine, who links the name Florence to the city, which, during the Renaissance, was home to countless artists who depicted idealized women in deathly situations.

Cities are a place of “beauty and death” for Varda, and she sought to convey these ideas against images of her attractive star, how surfaces (mirrors, windows) reflect her, and how the gazes of others rot and consume her. The juxtaposition of beauty and death proves so potent because Cléo is beautiful and surrounded by beautiful things. But gradually, Cléo’s anxiety strips her of all artifices, such as the masks she wears in everyday life, and forces her to confront her vulnerability and mortality, and therein her true self. “It is fear,” Varda wrote of her film’s central theme, “real and deep fear, that of death.” Still, Cléo’s fear of death is less about dreading what lies beyond this life and more about the possibility of no longer being beautiful. All but certain of her doom, Cléo finds a new understanding of selfhood with the soldier—a stranger, who engages with her feelings more than any of her dismissive friends. Finally, she and Antoine resolve to walk to the hospital where she was examined. After locating her doctor, whose bedside manner involves a sports car and no concern for his patient’s psychological state, Cléo learns she has cancer and will require radiation. The grave news has nonetheless relieved Cléo from her burden of fear. She admits, “I think my fear is gone. I think I’m happy.”

Cléo from 5 to 7 debuted in French theaters in April 1962 and played at the Cannes Film Festival the following month. The film’s mixture of vérité aesthetics and melodrama was celebrated in the press, even though it earned about one-twentieth of France’s top-grossing release that year, Yves Robert’s La Guerre des boutons (War of Buttons). Write-ups in Cahiers du Cinéma, Positif, and Les Temps Modernes praised Varda and the film, running lengthy interviews and critical analyses that considered the visual detail and meaning behind the film’s imagery, adding to the conversation that established Varda as a serious artist and her film worthy of such attention—even though critics such as Bernard Pingaud, who categorized the film as a documentary with its long takes and real-world setting, misread Varda’s intentions. Her contemporary filmmakers took notice as well. Michelangelo Antonioni called Cléo from 5 to 7 “a beautiful film by virtue of its sincerity.” But much of the writing about Varda and her film at the time—and subsequent analyses—talks about Varda in relation to the New Wave movement, which robs the filmmaker and her film of their distinctness. It’s easier and more commonplace to categorize using comparisons to established parameters than explore a film’s individuality.

Cléo from 5 to 7 debuted in French theaters in April 1962 and played at the Cannes Film Festival the following month. The film’s mixture of vérité aesthetics and melodrama was celebrated in the press, even though it earned about one-twentieth of France’s top-grossing release that year, Yves Robert’s La Guerre des boutons (War of Buttons). Write-ups in Cahiers du Cinéma, Positif, and Les Temps Modernes praised Varda and the film, running lengthy interviews and critical analyses that considered the visual detail and meaning behind the film’s imagery, adding to the conversation that established Varda as a serious artist and her film worthy of such attention—even though critics such as Bernard Pingaud, who categorized the film as a documentary with its long takes and real-world setting, misread Varda’s intentions. Her contemporary filmmakers took notice as well. Michelangelo Antonioni called Cléo from 5 to 7 “a beautiful film by virtue of its sincerity.” But much of the writing about Varda and her film at the time—and subsequent analyses—talks about Varda in relation to the New Wave movement, which robs the filmmaker and her film of their distinctness. It’s easier and more commonplace to categorize using comparisons to established parameters than explore a film’s individuality.

In the years since its release, the film has undergone several waves of reassessments, including rumors of a remake starring Madonna in the 1980s. More recently, the film earned its ranking as the fourteenth greatest ever made according to Sight and Sound’s 2022 critics’ poll. It has lasted because its themes remain timeless. Varda told interviewer Michel Capdenac that she sought to convey “a certain feeling of confusion, of chaos, the climate of fear that infects our lives.” Cléo’s brand of alienation and objectification continues today, though the interplay between public façades and personhood have grown even more complex in the wake of social media and those who maintain entirely online identities. Whereas Varda’s represented chaos derives from the city and her character’s womanhood, today, the digital realm makes the film achingly relatable, so her masterpiece continues to invite analysis among film scholars and feminist theorists. A ponderous film about beauty and death, objectivity and subjectivity, realism and expressionism, and the world that stifles yet enriches, Cléo from 5 to 7 churns with its central character’s anxiety and the innate conflict of modern life.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on June 28, 2023. )

Bibliography:

Conway, Kelley. Agnes Varda. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2015.

DeRoo, Rebecca J. Agnes Varda between Film, Photography, and Art. University of California Press, 2018.

Neroni, Hilary. Feminist Film Theory and Cléo from 5 to 7. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

Neupert, Richard John. A History of the French New Wave Cinema. Second Edition. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2007.

Ungar, Steven. Cléo from 5 to 7. BFI Film Classics. Second Edition. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review