The Definitives

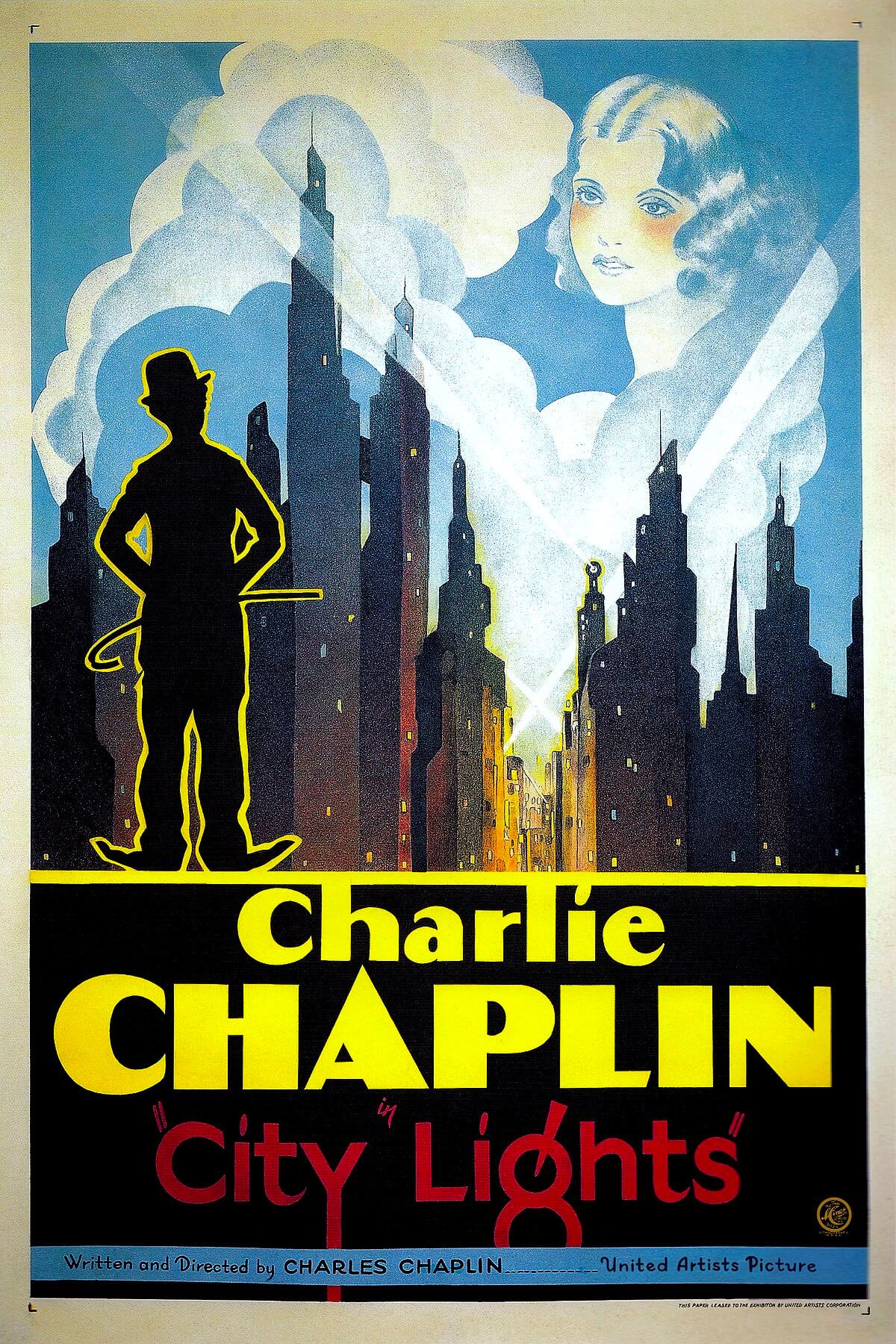

City Lights (1931)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

City Lights may be Charles Chaplin’s most personal motion picture, or perhaps the film’s heightened measure of emotion just makes it feel that way. Where else except someplace dear could a filmmaker develop a picture so touching and filled with such heart. Biographical parallels suggest that Chaplin derived the story from his past, whereas the filmmaker’s improvisational approach to directing suggests his stories never came effortlessly. As opposed to unswerving inspiration, the process from conception to completion often spanned several years. He labored over scenarios, this one in particular. And through his involved method, he sacrificed his personal life to feed his artistic drives. However, behind those drives dwelled an artist whose early years shaped his stories, consciously or not. After surviving a Dickensian childhood, his entertainer father a drunk and his singer mother subject to mental illness, a young Chaplin broke into moving pictures, though his early work was eclipsed with the debut of his iconic character The Tramp in 1914. Earning an international following, the world identified with the Tramp’s earthiness, his romanticism as an underdog, his lowly appearance so curiously dignified, and his rebellious agenda—not to mention Chaplin’s expert slapstick.

By 1919, less than a decade after his first appearance onscreen, Chaplin had become so popular and prosperous that he broke free of Hollywood’s studio system with Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. to form United Artists. Retaining total creative control, Chaplin elevated what before were masterful comic shorts into full-length features of pantomime and social commentary, earning millions in profits along the way. But Chaplin earned every cent of his then-unprecedented salary, as, during his independent productions, the director became more meticulous about the craft and artistry behind his films. He tested every comic bit again and again until he achieved perfection, no matter how long it took to get right. His education nil, Chaplin’s genius came from an instinctual understanding of motion and music; improvisation and experimentation were his greatest tools, his approach requiring multiple takes through a work-in-progress approach. When his inspiration failed him, whole sets were shut down, yet employees still received their checks. No matter how cost-ineffective this may have been, the outcome was rarely short of brilliance. Critics began to perceive his output as sophisticated filmmaking, and audiences made his Tramp character into one of the most iconic in pop-culture history—thus goes the story that Chaplin once himself entered in a “Chaplin Look-Alike” contest and earned a prize for third place.

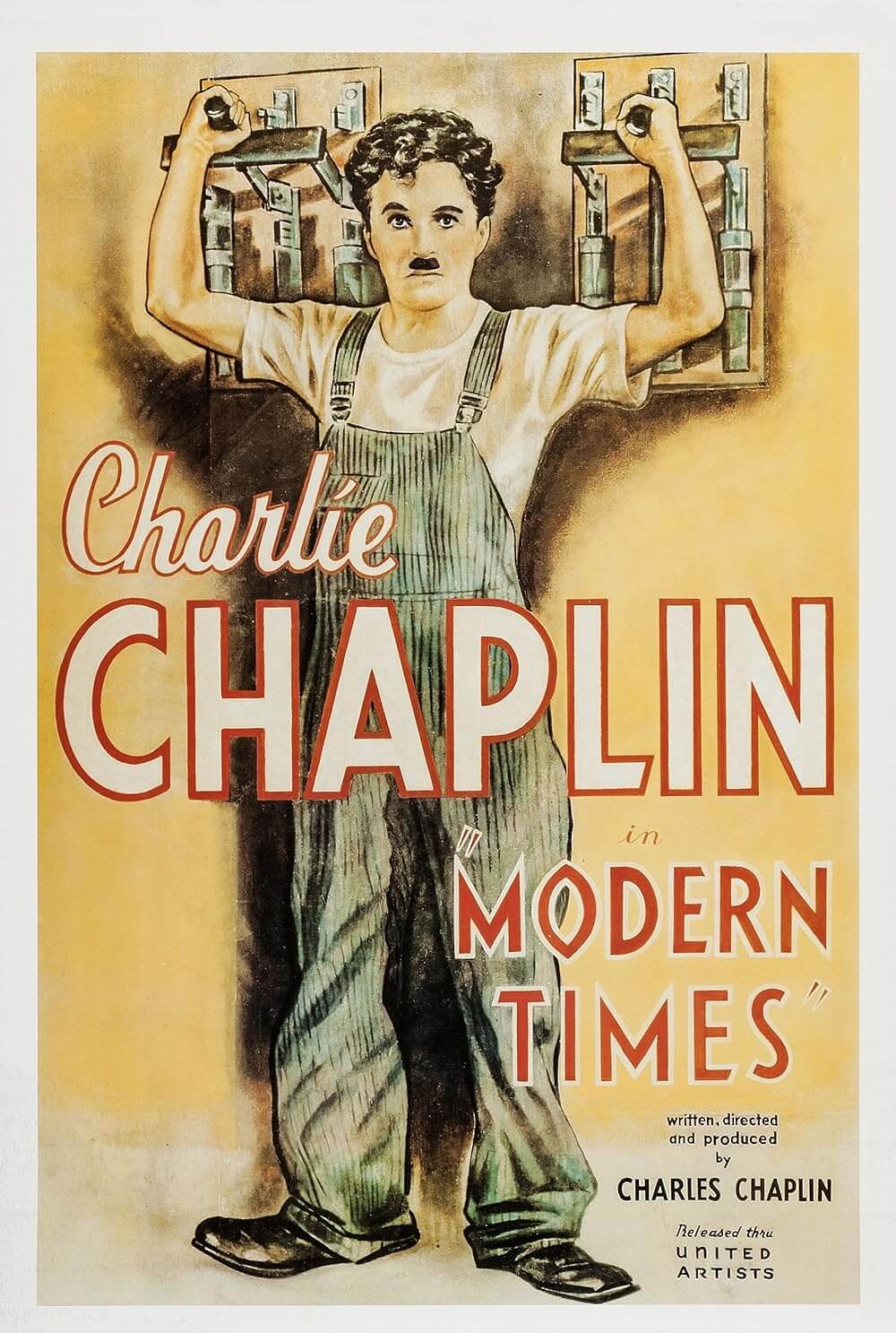

Though the filmmaker’s artistic instincts were impeccable, they faltered regarding the future of cinema. Chaplin began developing City Lights during the first rumblings of sound pictures, which he considered a temporary craze. In 1931, Chaplin gave Talkies “three years, that’s all.” But even as the industry migrated to sound as the standard format, Chaplin remained jealously dedicated to silent filmmaking. Having found his niche, he saw no reason to deviate. Technological advancements did not interest him, and only begrudgingly did he toy with sound in Modern Times some eight years after the first Talkies had spearheaded the new sound movement. Dialogue in movies forced Chaplin to consider his Tramp’s voice, what it would sound like, and how it would reduce his character. Quite correctly, he believed the Tramp communicated in a universal language free of words, whereas speech would limit the audience. Not until 1940, with The Great Dictator, did Chaplin make his first sound picture.

Though the filmmaker’s artistic instincts were impeccable, they faltered regarding the future of cinema. Chaplin began developing City Lights during the first rumblings of sound pictures, which he considered a temporary craze. In 1931, Chaplin gave Talkies “three years, that’s all.” But even as the industry migrated to sound as the standard format, Chaplin remained jealously dedicated to silent filmmaking. Having found his niche, he saw no reason to deviate. Technological advancements did not interest him, and only begrudgingly did he toy with sound in Modern Times some eight years after the first Talkies had spearheaded the new sound movement. Dialogue in movies forced Chaplin to consider his Tramp’s voice, what it would sound like, and how it would reduce his character. Quite correctly, he believed the Tramp communicated in a universal language free of words, whereas speech would limit the audience. Not until 1940, with The Great Dictator, did Chaplin make his first sound picture.

For City Lights, Chaplin and co-writer Harry Crocker began with a concept about a circus clown that loses his sight and attempts to conceal it from those around him. But Chaplin’s process proves more complicated than simply devising a scenario and seeing it through to fruition. His process has been called “labyrinthine,” and Chaplin himself described it like this: “I’ve got into the proposition, how do I get out?” City Lights eventually turned into another tale for Chaplin’s alter-ego, the Tramp, and the character’s adoration for a blind flower girl. Before he had a story for these characters, however, Chaplin had an ending: That moment when the now-seeing flower girl realizes the patron behind the surgery that cured her blindness is none other than the most unlikely of benefactors. And because Chaplin had perfected this last scene in his head, he toiled to develop a scenario worthy of it. Countless scenes and characters were developed only to be scrapped, subplots were included and then discarded, and the story changed repeatedly. Writing continued for well over a year before shooting began in December 1928, and still, Chaplin had much to work out both on the set and the page. Despite this considerable effort, the final plot as it appears onscreen earns its structural brilliance from its simplicity.

The Tramp wanders through an anonymous city and meets a fellow stray, a blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill), who, through happenstance, believes him a well-to-do citizen. Blindness remains the film’s prevailing theme, as the Tramp later comes upon an eccentric millionaire (Harry Myers) drunk and bent on suicide. The Tramp saves the millionaire from his alcoholic despair, and the millionaire responds with sumptuous entertainments and affection for his new friend. But when sober, the millionaire sees the Tramp as a waif and, having no memory of the night’s events, turns his new friend away. Likewise, the Tramp is drawn to the Flower Girl perhaps because she cannot see his poverty; he relishes her blindness, as she cannot judge him like so many others do (the sober millionaire, the millionaire’s butler, the newspaper boys, et al.) by his appearance.

The Tramp learns of a new cure for blindness in Vienna, but the girl needs money to pay her back rent and for the trip. As she believes him a wealthy man, the Tramp promises to get her the money and, in secret, takes various odd jobs, like street sweeper and boxer, to do so. Yet none earn him the payday he needs. In another lark with the inebriated millionaire, the Tramp benefits from his friend’s loosened generosity. But at the moment the glazed millionaire donates oodles of cash to the Tramp’s cause, his home is burglarized and soon swarming with police. The millionaire awakens from a blow to the head sober and cannot identify the Tramp—whose pockets are full of cash—as a friend, sending the Tramp on the run. He gets the money to the Flower Girl but soon finds himself captured and jailed by authorities. When released from prison, the Tramp emerges in sorrow. While wandering the streets, he once again finds the Flower Girl, who, now cured, has a flower shop of her own and dreams of meeting her benefactor, who surely must be rich and handsome. As the Tramp passes by her shop, he stops to gaze at the girl with delight; their eyes meet, but having never seen him before, she assumes he is another of the city’s many urchins. She attempts to give him some charity, but he motions away out of shame. At that moment, she touches his hand and recognizes him. “You?” she asks. He confirms with a nod, smiling. “You can see now?” She responds, “Yes, I can see now.”

The Tramp once again plays the protector for a female character in trouble, a theme that echoes throughout Chaplin’s oeuvre. Since the Flower Girl comes close to poverty, the impulsive and humanist Tramp steps forward to protect her purity; the next step down from a desperate flower girl, after all, is a prostitute. This subtextual rationale comes from a very personal place for the filmmaker, as Chaplin’s mother engaged in prostitution occasionally to support her son, a choice that led to the disease that caused her failure as a supporting parent and, ultimately, her mental illness. With that lesson in mind, Chaplin often wrote women characters for his Tramp to defend, saving them from falling over the brink that would otherwise lead them to a life of shame. Given Chaplin’s personal insights, the Tramp’s heroism rarely plays like that of a gallant lover; rather, he is a boy trying to protect his mother. Thus, the Tramp’s mannerisms often seem “infantile” and childlike. Freud called Chaplin’s on and offscreen similarities “transparent,” but the filmmaker’s openness to his audience, his willingness to depict reality no matter how grim, rises above psychoanalysis to touch worldwide moviegoers.

As another personal inspiration, the Flower Girl stands as the fictional counterpart to Chaplin’s would-be lover Henrietta “Hetty” Kelly, a woman Chaplin courted in vain and obsessed over for years to come, and who would shape his future sexual desires for younger women. They met in 1908. She was a dancer, and after a show, Chaplin greeted her, setting off a brief but devastating courtship. He was fascinated with her beauty, youth, and elusiveness. Their dates never lasted more than twenty minutes and consisted of walks on which Chaplin escorted Hetty to her dance rehearsals. His wooing began on Monday, lasted through Wednesday, but by Thursday, he was met by Hetty’s mother, Eliza, who explained they could no longer see each other. Chaplin saw Hetty after contesting the issue, but she remained stand-offish. Chaplin wrote of this affair: “The episode was but a childish infatuation to her, but to me it was the beginning of a spiritual development, a reaching out for beauty.” They exchanged at least one letter as the years went on, and Chaplin became close friends with her brother, but Hetty soon died in 1918 from complications with pneumonia brought about from an influenza epidemic. For Chaplin, City Lights allowed him to save both Hetty and his mother in a way he never could in life.

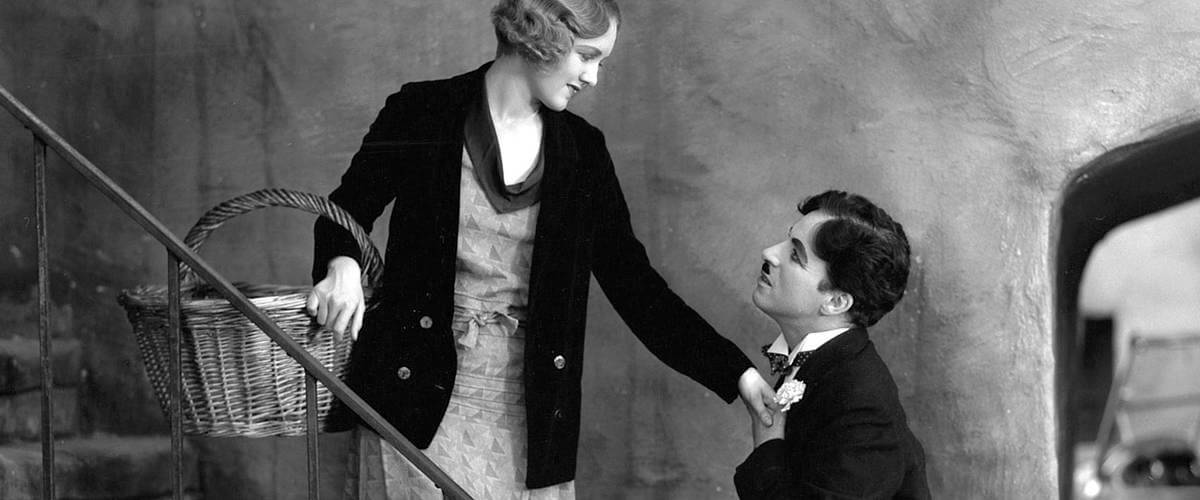

For his cast, Chaplin included players from his usual company: Allan Garcia played the snooty butler, and Hank Mann played the prizefighter. He hired Virginia Cherrill for his Flower Girl after seeing her at a boxing match; Chaplin approached Cherrill about the role, and she tested the next day. He admired her ability to look “inwardly,” avoiding the other way actors played blind—by rolling their eyes back in what he called a “repulsive manner.” Despite his initial attraction and appreciation for her acting style, Chaplin and Cherrill never much liked each other, a fact both would later openly admit. Their first scene together onscreen was also the first filmed, where her Flower Girl offers the Tramp a blossom, asking “Flower, sir?” Take after take turned into days of shooting this same scene until Cherrill spoke the line with the precise rhythm that Chaplin wanted, even though no one would hear her spoken words. Troubles persisted on other scenes, and after a year of shooting, Chaplin fired Cherrill; he filmed scenes with another actress, Georgia Hale, but she failed to capture the part. Cherrill was eventually rehired to complete production, and she renegotiated her contract to double what she was earning before.

For his cast, Chaplin included players from his usual company: Allan Garcia played the snooty butler, and Hank Mann played the prizefighter. He hired Virginia Cherrill for his Flower Girl after seeing her at a boxing match; Chaplin approached Cherrill about the role, and she tested the next day. He admired her ability to look “inwardly,” avoiding the other way actors played blind—by rolling their eyes back in what he called a “repulsive manner.” Despite his initial attraction and appreciation for her acting style, Chaplin and Cherrill never much liked each other, a fact both would later openly admit. Their first scene together onscreen was also the first filmed, where her Flower Girl offers the Tramp a blossom, asking “Flower, sir?” Take after take turned into days of shooting this same scene until Cherrill spoke the line with the precise rhythm that Chaplin wanted, even though no one would hear her spoken words. Troubles persisted on other scenes, and after a year of shooting, Chaplin fired Cherrill; he filmed scenes with another actress, Georgia Hale, but she failed to capture the part. Cherrill was eventually rehired to complete production, and she renegotiated her contract to double what she was earning before.

Chaplin dedicated himself to perfecting every scene during both the writing process and on the set. Sacrificing his personal life during production to “do it all” himself, he washed over devastating events like prolonged illness and his mother’s death in August 1928 by returning to work. His desire for perfection extended from constantly rethinking every scene to somewhat neurotic choices for authenticity’s sake. For the house party sequence at the millionaire’s home, Chaplin hired a real singer for $50 a day to sing the party ballad (which the Tramp would interrupt with whistle-infused hiccups) to give his party players the feel of an actual celebration. He believed no actor could mime what a singer does for real. Such choices were as much about embracing extravagances as they were about realism, however. Writing, direction, choreography, and even music received Chaplin’s personal touch. He became interested in composing each of his films after his 1923 dramatic silent, A Woman of Paris, a commercial failure that also announced Chaplin’s desire for serious filmmaking. A child prodigy for music, he was not versed in the language or science of musical composition. As he told the New York Telegram at the premiere for City Lights, it was another one of his masterful instincts: “I really didn’t write it down. I la-laed and Arthur Johnston wrote it down.” Chaplin formulated musical themes throughout for specific characters, with Jose Padilla’s “La Violetera” a prominent theme for the dramatic transitions. During his silent years, Chaplin’s own scores acted as the voice of his work.

Even after the exhaustive principal shoot, which lasted until August 1930, Chaplin reshot scenes or added entire subplots and comic asides into the film. The harassing newsboys that blow peas at the Tramp, for example, were added later. The final scene filmed was ironically the first envisioned by Chaplin, the last moments between the Tramp and the Flower Girl. And unlike the rest of the production, perhaps because Chaplin had visualized the scene so clearly and so long ago, the sequence was completed without incident, in one afternoon no less. Chaplin himself attributed the ease of filming the scene to “a great deal of magic.”,Film critic and writer James Agee (screenwriter of The African Queen and The Night of the Hunter) wrote, “It is enough to shrivel the heart to see, and it is the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies.” To be sure, Agee’s enthusiasm was not unwarranted. Those final shots of City Lights soften the viewer and bring tears of joy with almost supernatural power; Chaplin’s profound understanding of sentimentality has never been captured in a purer moment.

After the long editing process, Chaplin held a surprise prescreening at LA’s Tower Theater and gave a heartfelt comedy to audiences expecting to see the billed adventure yarn. Their negative responses incited Chaplin to feverishly re-edit some scenes, changing only superficial details. In January 1931, City Lights premiered at the new Los Angeles Theater, a modernized moviehouse to rival today’s amenity-driven multiplexes—complete with soda fountains, a restaurant, and a crying room, plus luxuries like an art gallery and French cosmetics room. Chaplin invited everyone in Hollywood, sparing no expense, while his personal guests were Albert Einstein and his wife. Huge crowds in attendance called for police to usher the throng. And aside from management stopping the show mid-film to ask guests to enjoy the new theater’s extravagances—at which point the audiences booed until the show resumed—the response was wholeheartedly enthusiastic. As a result, a film released in the midst of the Talkie breakthrough reminded audiences and critics of Chaplin’s genius and relevancy.

After the long editing process, Chaplin held a surprise prescreening at LA’s Tower Theater and gave a heartfelt comedy to audiences expecting to see the billed adventure yarn. Their negative responses incited Chaplin to feverishly re-edit some scenes, changing only superficial details. In January 1931, City Lights premiered at the new Los Angeles Theater, a modernized moviehouse to rival today’s amenity-driven multiplexes—complete with soda fountains, a restaurant, and a crying room, plus luxuries like an art gallery and French cosmetics room. Chaplin invited everyone in Hollywood, sparing no expense, while his personal guests were Albert Einstein and his wife. Huge crowds in attendance called for police to usher the throng. And aside from management stopping the show mid-film to ask guests to enjoy the new theater’s extravagances—at which point the audiences booed until the show resumed—the response was wholeheartedly enthusiastic. As a result, a film released in the midst of the Talkie breakthrough reminded audiences and critics of Chaplin’s genius and relevancy.

Having gathered the general public’s attention early in his career, Chaplin later forced intellectuals to look more critically at film in a time when it was not yet considered art, beginning with A Woman of Paris and then City Lights. It is easy to appreciate why Depression-era audiences admired the Tramp for his freedom, childlike reactions, ability to escape responsibility whenever he chooses, and find another odd job or town to call home when things get rough. Rules and social hierarchies eluded him, leaving him content and even happy in his poverty—a crucial element for the period’s viewers in terms of his comic effect and escapism. In time, after his popularity was solidified, comparisons between Chaplin and the classical comedians, most commonly Aristophanes, became impossible to ignore. From his tragic origins and meticulous artistry, Chaplin created a universal artform in the cinema; his wide-ranging comedy and subjects appealed to the masses and marked his sudden rise to fame, entrenching his status as an icon.

Today, City Lights remains a cinematic miracle, a most singular example of Chaplin’s effect on audiences. The wonderful opening scene when kazoo-voiced politicians unveil the city’s newest statue and uncover the Tramp asleep in its bronze contours demonstrates Chaplin’s subversiveness, whereas the fanciful comedic suspense when the Tramp just misses falling into a sewer shaft captures his expertise in elaborate gags. Or the ballroom scene, when the Tramp eats his pasta dinner and by mistake begins munching down party ribbon, his eyes acutely aware of the error while his mouth continues to consume on autopilot; or his long struggle to keep the drunken millionaire from drowning; or the careful fight choreography on display during the boxing match. These moments have no present-day counterpart in terms of ingenuity or polish; every situation is fully realized to its limits without arrogance—his picture never feels bloated, showing only what needs to be shown with a master’s discretion. More than a study of his techniques and methods, the magic of Chaplin’s work becomes apparent when his comedy, sentimentalism, choreography, and music come together. Perhaps because Chaplin constructed City Lights from such personal origins, any viewer will be taken by the film, no matter their language or country or moment in time. The story’s simplicity and the presentation’s complexity achieve a poignant whole, in turn proving the effectiveness of silent filmmaking—the power of images. By tapping into universal emotions, Chaplin’s reach goes beyond cinema’s usual confines and renders his work among the purest definitions of timeless filmmaking.

Bibliography:

Chaplin, Charles. My Autobiography. Simon & Schuster, 1964.

Okuda, Ted; Maska, David. Charlie Chaplin at Keystone and Essanay: Dawn of the Tramp. iUniverse, New York, 2005.

Robinson, David. Chaplin: His Life and Art. McGraw-Hill, second edition, 2001.

Schickel, Richard. The Essential Chaplin: Perspectives on the Life and Art of the Great Comedian. Chicago: I.R. Dee, 2006.

Vance, Jeffrey. Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review