The Definitives

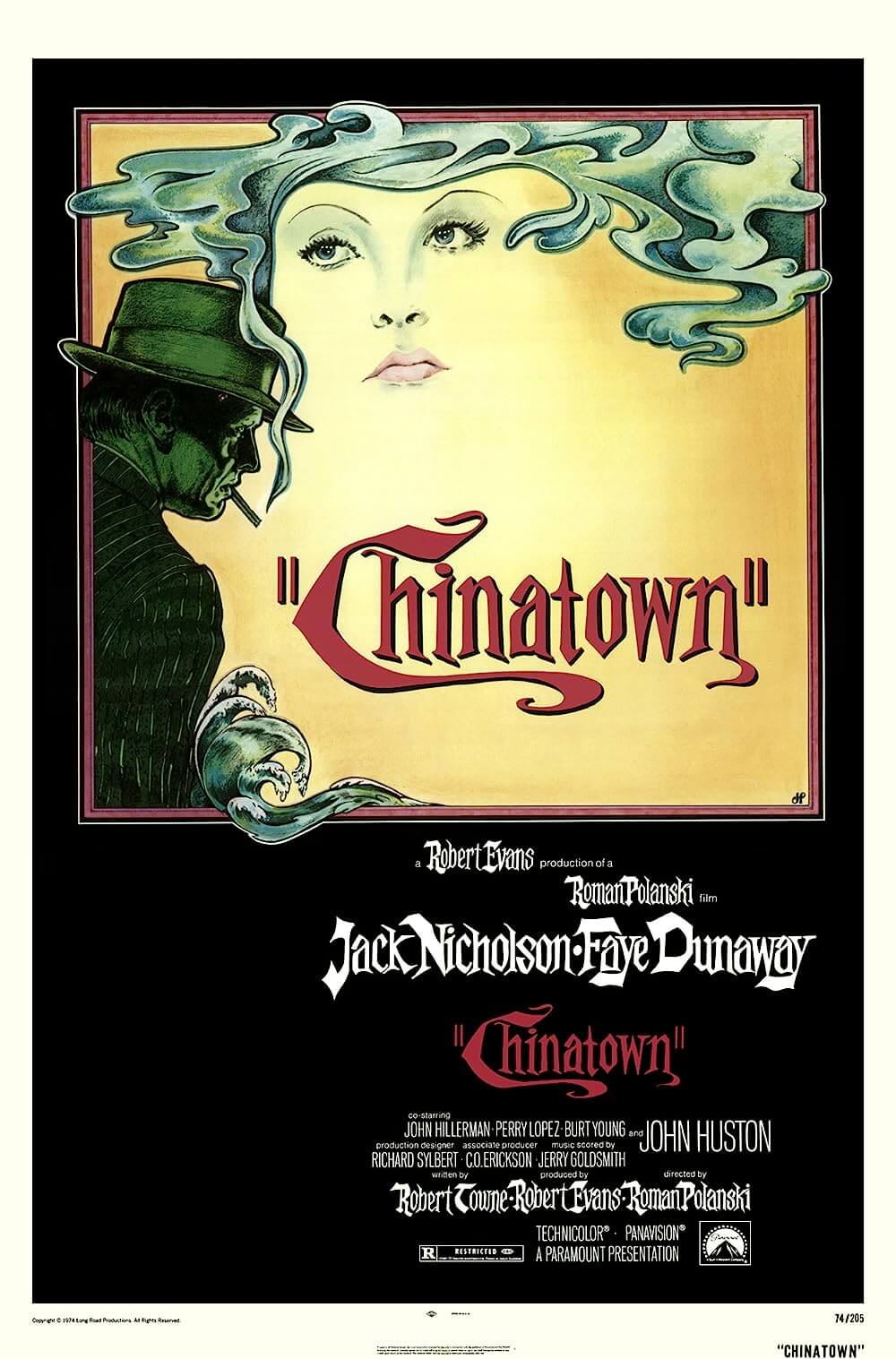

Chinatown (1974)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

When Mrs. Evelyn Mulwray, wife to Water & Power head Hollis Mulwray, tells Private Detective Jake Gittes that she wants to hire him to follow her husband because she believes he’s having an affair, Jake stops her: “Mrs. Mulwray, can I give you some advice. Do you know the expression ‘let sleeping dogs lie’? You’re better off not knowing.” Then again, operating in 1930s Los Angeles, then just a burgeoning city in the desert, Mr. Mulwray is a prominent figure. For Jake, a case like this is irresistible. And so, rather than take his own advice, Jake follows and eventually photographs his client’s husband “involved” with a young woman. Except, unbeknownst to Jake, Mrs. Mulwray is not Mrs. Mulwray. Jake has been set up as part of a conspiracy larger and more complex than he can imagine: a deal to secure water to irrigate and develop land for the expansion of L.A. into the Valley. Jake’s photos of Mr. Mulwray somehow make the newspaper the next morning when, in all his obliviousness, he enjoys a shave at a barbershop. Out of the shop’s window, we notice a genius detail inserted by director Roman Polanski. Looking into the street, we see a man fumble with a steaming car whose radiator has overheated and burst. This is what happens when someone like Jake meddles with something as elemental as water and those who control it—things get hot, and they explode.

Countless other instances of symbolic foreshadowing, many of them related to water or obscured vision, hint that Jack Nicholson’s Jake Gittes cannot see the bigger picture in Chinatown, a complexly structured film with multiple meanings for every scene. In turn, the viewer requires several viewings to discover and appreciate its secrets and intricacy. This persistent sense of uncertainty emasculates Jake and drives the film’s core themes. The opposition’s players are too powerful, and the stakes are so beyond Jake’s control that every effort he makes to act meaningfully proves wasted, although neither the audience nor Jake is aware of it yet. With much input from Polanski, Robert Towne wrote the screenplay and placed the viewer in an unseeing and unknowing state of mind always set in Jake’s perspective. And like him, we think we know what’s going on, but we never do, not until the final moments. At first glance, this 1974 film suggests a neo-noir throwback. However, Polanski’s predilection for obsessive detail, fatalistic and ironical conclusions, and unconventional storytelling transform the result into an unforgettable and unique motion picture that embodies classic detective film noir thirty years after its zenith.

Apart from Polanski, whose vision reshaped Towne’s initial ideas, credit for the film ever being made belongs to producer Robert Evans, the David O. Selznick of the sixties and seventies. A former radio talent and bit film actor who would eventually become Vice President in Charge of Production at Paramount Pictures, Evans single-handedly revived the ailing studio in the sixties with hits like True Grit, The Odd Couple, and Love Story. In time, Evans was given his own banner under which he produced projects independent from Paramount executive control. For his first of these, he went to Robert Towne, whose script for The Last Detail had earned the writer accolades. Evans offered Towne $175,000 to adapt The Great Gatsby, but the writer declined, admitting he could not improve upon F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel. Towne instead asked Evans for $25,000 to write an original detective story. Towne meticulously researched and loosely based his screenplay on actual Water & Power department head William Mulholland, the public figure at the center of a subterfuge to obtain water for Los Angeles from Owens Valley. Towne also drew inspiration from a Hungarian vice cop who sold him a dog; the cop told the writer of his experience in Chinatown, saying, “You don’t know who’s a crook and who isn’t a crook, so don’t do a goddamned thing.”

Apart from Polanski, whose vision reshaped Towne’s initial ideas, credit for the film ever being made belongs to producer Robert Evans, the David O. Selznick of the sixties and seventies. A former radio talent and bit film actor who would eventually become Vice President in Charge of Production at Paramount Pictures, Evans single-handedly revived the ailing studio in the sixties with hits like True Grit, The Odd Couple, and Love Story. In time, Evans was given his own banner under which he produced projects independent from Paramount executive control. For his first of these, he went to Robert Towne, whose script for The Last Detail had earned the writer accolades. Evans offered Towne $175,000 to adapt The Great Gatsby, but the writer declined, admitting he could not improve upon F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel. Towne instead asked Evans for $25,000 to write an original detective story. Towne meticulously researched and loosely based his screenplay on actual Water & Power department head William Mulholland, the public figure at the center of a subterfuge to obtain water for Los Angeles from Owens Valley. Towne also drew inspiration from a Hungarian vice cop who sold him a dog; the cop told the writer of his experience in Chinatown, saying, “You don’t know who’s a crook and who isn’t a crook, so don’t do a goddamned thing.”

Evans had previously struck gold with Polanski on Rosemary’s Baby in 1968, and the producer rightly believed the paranoid sense of unknowing in Towne’s script fit the director’s style. When Polanski joined on, his return to Hollywood filmmaking was a comeback in many ways. For example, just three years earlier, his pregnant wife Sharon Tate was murdered by the Mason family, while his subsequent films, MacBeth (1971) and What? (1973), both independents were flops by commercial standards. Exacting his renowned, almost compulsive control, Polanski demanded Towne cut down the original 180-page screenplay, although the writer believed his initial script was perfect. At first, Towne wanted just a Water & Power scandal but later incorporated the more basic, dramatic conflict between men and women, which Polanski wanted emphasized even more, including a scene where Gittes and Evelyn go to bed. Most important to Polanski was not “cheating” the audience, which he felt Towne’s original screenplay did by containing no scenes in Chinatown, only mere references. Instead, Polanski wanted the finale to take place in Chinatown and the ending to play out in a high drama worthy of Greek tragedy (Oedipus comes to mind). Towne’s “love conquers all” version of the script features the villain’s death and the hero getting away with the girl. But Polanski believed if they were to truly make a “modern” detective story in a nineteen-thirties setting, they must employ a disastrous conclusion to set it apart from the genre’s conventions. Polanski and Towne clashed on these points during the rewrite process, as the director insisted on changes to the plot, lines of dialogue, individual words, and even punctuation. But without his contributions, it’s doubtful Chinatown would have become such a classic of rebellious seventies filmmaking.

Evans saw the production as something akin to The Godfather (1972) and attempted to steer Polanski, albeit unsuccessfully, down that stylistic road. The producer even insisted on using The Godfather’s cinematographer, Gordon Willis, who was unavailable at the time. In Willis’ place, hoping for a classicized look, Evans hired Stanley Cortez, a venerated Old Hollywood photographer who shot Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), among other classics. Evans even had the printing labs turn out the day’s rushes in what Polanski called “tomato ketchup” to recapture the sepia-tone style of The Godfather. Polanski fired Cortez after ten days for his overreliance on classical techniques and out-of-date technology. However, Cortez’s vast experience in an older style of filmmaking served Charles Laughton well when they intentionally evoked classical cinema with The Night of the Hunter (1955). But Polanski was nothing if not modern. John A. Alonzo (Harold and Maude, 1971) replaced Cortez and avoided any outright noirish influence, such as cocked angles and other expressionist traits. Just as Polanski’s additions to the script modernized the material, Alonzo used modern camera techniques to tell a classicized story. Polanski also clashed with Evans on casting. The producer wanted Jane Fonda for Evelyn Mulwray; Polanski wanted Faye Dunaway. He got his way when Fonda turned down the role (much to his chagrin later on, as Polanski and Dunaway’s personalities collided in a famous offscreen row). Such disagreements continued and eventually spoiled the professional relationship between Evans and Polanski behind the scenes. At the same time, the director’s victory in most creative decisions left the film a singularly envisioned work, earning eleven Academy Award nominations in 1975, including a nomination to Polanski for his direction and a win to Towne for his screenplay.

Evans saw the production as something akin to The Godfather (1972) and attempted to steer Polanski, albeit unsuccessfully, down that stylistic road. The producer even insisted on using The Godfather’s cinematographer, Gordon Willis, who was unavailable at the time. In Willis’ place, hoping for a classicized look, Evans hired Stanley Cortez, a venerated Old Hollywood photographer who shot Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), among other classics. Evans even had the printing labs turn out the day’s rushes in what Polanski called “tomato ketchup” to recapture the sepia-tone style of The Godfather. Polanski fired Cortez after ten days for his overreliance on classical techniques and out-of-date technology. However, Cortez’s vast experience in an older style of filmmaking served Charles Laughton well when they intentionally evoked classical cinema with The Night of the Hunter (1955). But Polanski was nothing if not modern. John A. Alonzo (Harold and Maude, 1971) replaced Cortez and avoided any outright noirish influence, such as cocked angles and other expressionist traits. Just as Polanski’s additions to the script modernized the material, Alonzo used modern camera techniques to tell a classicized story. Polanski also clashed with Evans on casting. The producer wanted Jane Fonda for Evelyn Mulwray; Polanski wanted Faye Dunaway. He got his way when Fonda turned down the role (much to his chagrin later on, as Polanski and Dunaway’s personalities collided in a famous offscreen row). Such disagreements continued and eventually spoiled the professional relationship between Evans and Polanski behind the scenes. At the same time, the director’s victory in most creative decisions left the film a singularly envisioned work, earning eleven Academy Award nominations in 1975, including a nomination to Polanski for his direction and a win to Towne for his screenplay.

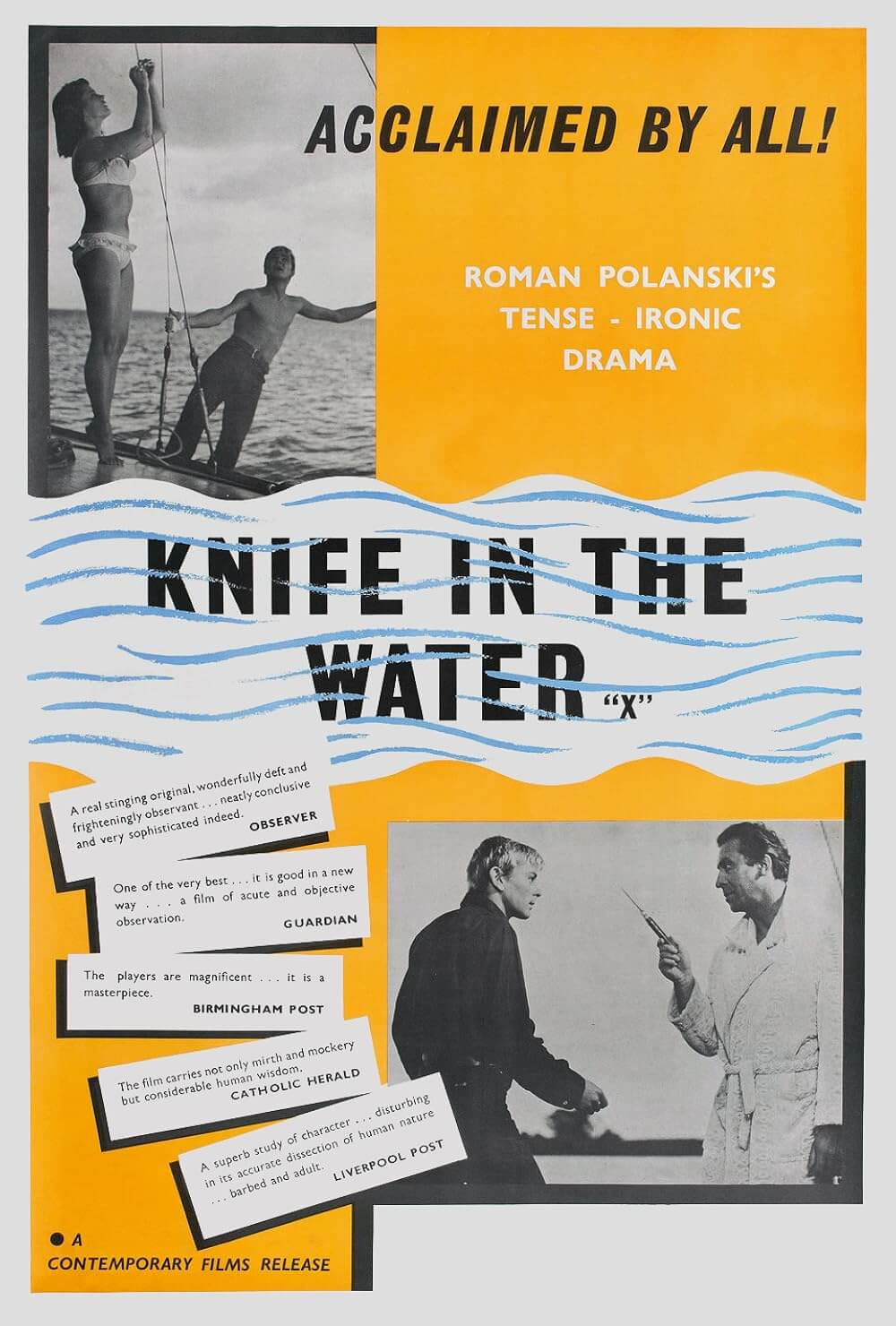

Indeed, Chinatown is decidedly a Roman Polanski film in that it follows a particular story structure attributable to his career during this period, wherein his customarily naïve protagonist is wrapped inside a mystery or situation they cannot understand. However desperately they try to gain control over or even comprehend the situation, their helplessness leads them to a conclusion that ultimately overwhelms them. This is the case with Knife in the Water, Repulsion, Rosemary’s Baby, Macbeth, and after Chinatown, The Tenant. Here, Jack Nicholson plays Jake Gittes with sublime confidence, a breakthrough and Oscar-nominated role. But, unfortunately, Jake sees everything from the wrong perspective, a critical and repeated downfall for the character, we learn. Jake’s terminal flaw is that he needs to know. And when he meets the real Mrs. Evelyn Mulwray (Dunaway), he feels both of them have been played by a mystery third party, by whoever hired the fake Mrs. Mulwray (Diane Ladd), to bring Hollis Mulwray down. He does not mind bad publicity per se; later, someone reminds him that such a reputation is almost commendable in his profession (or métier, as Jake calls it). But he cannot be made a fool. Jake’s mission throughout the film then becomes one of reestablishing his position of authority. After all, as a private investigator, he’s accustomed to being in control, taking the photos, and telling his clients what’s really going on. His pride takes him from one lead to the next, and he uncovers a plot to divert water from Owens Valley orange groves via the L.A. reservoir into the Valley. Thousands of acres of land have already been purchased to make untold millions in profits when cultivated and sold. But when someone murders Hollis Mulwray so it looks like he committed suicide, it becomes more than a land deal; it becomes a murder mystery.

In this, the film embodies the detective genre defined by Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. Still, it takes the experience somewhere else entirely, even while occupying rather than redefining the genre, unlike modern equivalents such as The Long Goodbye (1973). Jake has more in common with Charlie Chan, Phillip Marlowe, and Sherlock Holmes than any modern detectives. And yet, released amid seventies conspiracies like Watergate and the Vietnam War, the film tells a very “modern” story, one whose central mystery is less about finding answers than Jake escaping, if not accepting his own mindset. Jake references his experience as a cop in Chinatown, how he once tried to save a woman in danger there, but his inability to grasp the full magnitude of the situation that in turn caused her harm. Chinatown is a place as much as it is a mental state where one cannot see beyond their status; as a private eye, Jake’s status is meager, to be sure. When Jake runs into a former Chinatown cop, Escobar (Perry Lopez)—who, having been promoted to Lieutenant since he and Jake worked together, now understands the bigger picture—the Lieutenant explains, “I’m out of Chinatown now.” Chinatown, then, is defined as a place where it’s impossible to know who’s who and what’s what; therefore, it’s best just not to get involved. Escobar is smart enough to realize the limitations of his status. Jake’s mistake is that he’s compelled to become involved once more to solve the Hollis Mulwray mystery, and he puts those around him, mainly Evelyn, in danger. His out-of-his-element state, call it his Chinatown Syndrome, prevents him from recognizing the greater threats or doing anything to prevent them.

In this, the film embodies the detective genre defined by Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. Still, it takes the experience somewhere else entirely, even while occupying rather than redefining the genre, unlike modern equivalents such as The Long Goodbye (1973). Jake has more in common with Charlie Chan, Phillip Marlowe, and Sherlock Holmes than any modern detectives. And yet, released amid seventies conspiracies like Watergate and the Vietnam War, the film tells a very “modern” story, one whose central mystery is less about finding answers than Jake escaping, if not accepting his own mindset. Jake references his experience as a cop in Chinatown, how he once tried to save a woman in danger there, but his inability to grasp the full magnitude of the situation that in turn caused her harm. Chinatown is a place as much as it is a mental state where one cannot see beyond their status; as a private eye, Jake’s status is meager, to be sure. When Jake runs into a former Chinatown cop, Escobar (Perry Lopez)—who, having been promoted to Lieutenant since he and Jake worked together, now understands the bigger picture—the Lieutenant explains, “I’m out of Chinatown now.” Chinatown, then, is defined as a place where it’s impossible to know who’s who and what’s what; therefore, it’s best just not to get involved. Escobar is smart enough to realize the limitations of his status. Jake’s mistake is that he’s compelled to become involved once more to solve the Hollis Mulwray mystery, and he puts those around him, mainly Evelyn, in danger. His out-of-his-element state, call it his Chinatown Syndrome, prevents him from recognizing the greater threats or doing anything to prevent them.

Jake suffers from what Towne calls “the futility of good intentions,” a near compulsive drive that impels his search no matter what harm befalls him. This compulsion also carries over to the audience, as Polanski delivers the film from Jake’s subjective point-of-view. We know only what Jake knows, save for one exception when he retells a dirty joke to his associates. But unbeknownst to him, Evelyn Mulwray is standing right behind him. This is their first encounter and denotes her power over him as a femme fatale. At the outset, his investigation progresses with only minor obstacles and awkward waiting, littered with Polanski’s comic use of quirky “gate-keeper” characters to present negligible annoyances for Jake: Mulwray’s irritated secretary; Evelyn’s Chinese butler; the snooty, pimple-faced records keeper. These often humorous tropes suddenly develop into something far more dangerous when Jake investigates the reservoir and finds evidence of water runoff. But he also finds two goons, water department security Claude Mulvihill (Roy Jenson) and a “midget” henchman (Polanski himself) with a knife. Jake’s nostril pays the penalty of poking his nose where it doesn’t belong when Polanski’s henchman slices it, introducing an aspect of violence not yet felt in the film. This is a wound the director refuses to grant a miraculous overnight movie recovery for; instead, Jake spends most of the remaining film with a deliberately distracting white bandage on his nose. And after he removes the bandage, we see his visibly stitched-up wound. It’s a constant reminder that Jake’s investigation is going places it should not. Worse, given his Chinatown history, this is a lesson he should have already learned.

Evelyn is the personification of Jake’s Chinatown Syndrome because she remains unknowable for much of the picture, and because her fate mirrors that of Jake’s earlier experiences in Chinatown. More even than the secrets of the plot, Evelyn is the film’s mystery. As her father later warns about her, “You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but believe me, you don’t.” Jake replies, “That’s what the District Attorney used to tell me in Chinatown.” She responds to Jake’s questions with enigmatic answers, enough to satisfy the need for a reply but without addressing the question itself. At first, she seems cold and in control, but when Jake begins to ask the wrong questions, getting her into bed becomes easy—if only, in part, as a deflection. She seems confident, and then she grows nervous and stutters whenever Jake mentions her father’s name or their association. Jake never knows if he can trust her, and just when he feels he can, she deceives him. What we come to learn of her is that, in her youth, she had an incestuous affair with her father. The affair produced a child, who grew up into the young woman with whom Hollis was involved. Not even a man of Jake’s experience can grasp it. When he confronts her about Hollis’ mistress, who Evelyn now apparently keeps a prisoner in her home, Jake wants answers. Finally, he’s had enough; he resolves to slap it out of her. Evelyn weepily concedes, “She’s my daughter.” Jake refuses to believe it—slap! “She’s my sister.” Slap! “She’s my daughter.” Slap! And so on. Finally, her shame is revealed: “She’s my sister and my daughter!” Despite her trauma, Evelyn is a femme fatale in the classic noir sense: solitary, full of secrets, and ultimately doomed. And like any noir hero, how could Jake help but love her?

Evelyn is the personification of Jake’s Chinatown Syndrome because she remains unknowable for much of the picture, and because her fate mirrors that of Jake’s earlier experiences in Chinatown. More even than the secrets of the plot, Evelyn is the film’s mystery. As her father later warns about her, “You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but believe me, you don’t.” Jake replies, “That’s what the District Attorney used to tell me in Chinatown.” She responds to Jake’s questions with enigmatic answers, enough to satisfy the need for a reply but without addressing the question itself. At first, she seems cold and in control, but when Jake begins to ask the wrong questions, getting her into bed becomes easy—if only, in part, as a deflection. She seems confident, and then she grows nervous and stutters whenever Jake mentions her father’s name or their association. Jake never knows if he can trust her, and just when he feels he can, she deceives him. What we come to learn of her is that, in her youth, she had an incestuous affair with her father. The affair produced a child, who grew up into the young woman with whom Hollis was involved. Not even a man of Jake’s experience can grasp it. When he confronts her about Hollis’ mistress, who Evelyn now apparently keeps a prisoner in her home, Jake wants answers. Finally, he’s had enough; he resolves to slap it out of her. Evelyn weepily concedes, “She’s my daughter.” Jake refuses to believe it—slap! “She’s my sister.” Slap! “She’s my daughter.” Slap! And so on. Finally, her shame is revealed: “She’s my sister and my daughter!” Despite her trauma, Evelyn is a femme fatale in the classic noir sense: solitary, full of secrets, and ultimately doomed. And like any noir hero, how could Jake help but love her?

Chinatown’s detective story elements and air of fatalism align the film within the classic film noir schema. Still, an all too common interpretation suggests Polanski’s film is neo-noir solely because it was made thirty years after the style’s 1940s heyday. Of course, this raises an old debate about how we define film noir, whether it is a style or genre, and whether anything can be called “true film noir” outside of its ‘40s prime. Chinatown uses noir story motifs (the private detective; the femme fatale; the corrupt villain; the MacGuffin; the dynamic downturned conclusion) but few of its visual traits (chiaroscuro monochrome photography; heavy use of shadows; diagonal camera angles). While the label of neo-noir implies certain innovations, Polanski’s flourishes, save for the shocking incest plot point, are subtle enough to suggest his film is evidence that true film noir did not end in the forties. While not retro cinema or an imitation of classic film noir through black-and-white photography, the picture occupies the thirties setting without irony in a thorough rebuilding of the era’s décor and costumes. That the film does not attempt to imitate classic film noir is a testament to it occupying that very condition. Polanski does not overemphasize his mise-en-scène until it becomes impossible to ignore. Yet, we see the setting through modern eyes—which is to say, we see the film through the definitions of seventies cinema that is certainly broader than that of the forties in terms of censorship, allowing for a more salacious story to be told. Chinatown is a film neither wholly representing the thirties, forties, or the seventies; today, it feels timeless. And in its singularity, it assumes the identity of true film noir.

How appropriate then that Chinatown’s villain, land magnate Noah Cross (John Huston), seems to embody a timeless, unfathomable evil, his name by design meant to evoke ancient Christian imagery in its allusion to Noah’s flood and the crucifix. Cross, Hollis Mulwray’s former partner, is absolutely corrupt, devilishly charming, and confident in the superiority his money and reputation can buy. “‘Course I’m respectable. I’m old,” Cross quips. “Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough.” When Jake first meets Cross at his estate, they have lunch together—a plate of fish served head-on. Cross’ message is subtle: Jake is a fish-out-of-water and about to be cooked. From vast but shady land deals to incest, the key to Cross’ evil is his capacity to rationalize. Consider the way he hesitates at first when, like a spider approaching its prey, he tells his (grand)daughter Katherine (Belinda Palmer) that he’s her grandfather; he stutters, pauses to rationalize, and now certain he proceeds—“I am your grandfather.” Towne’s incest plot is meant to dramatize Cross’ rape of the land for the sake of “the future” in a grand symbolic expression. This comparatively smaller crime represents the degree to which his manipulation of public services is vile and unforgivably corrupt. But Cross’ is evil beyond political corruption or his incestuous transgressions—his evil is transcendent in that it justifies itself for a perceived better future. For Jake, Cross, too, personifies his Chinatown Syndrome, as the man remains immeasurably wicked, untouched by authorities, and wholly necessary for progress, which Jake’s transparent sense of justice cannot comprehend.

How appropriate then that Chinatown’s villain, land magnate Noah Cross (John Huston), seems to embody a timeless, unfathomable evil, his name by design meant to evoke ancient Christian imagery in its allusion to Noah’s flood and the crucifix. Cross, Hollis Mulwray’s former partner, is absolutely corrupt, devilishly charming, and confident in the superiority his money and reputation can buy. “‘Course I’m respectable. I’m old,” Cross quips. “Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough.” When Jake first meets Cross at his estate, they have lunch together—a plate of fish served head-on. Cross’ message is subtle: Jake is a fish-out-of-water and about to be cooked. From vast but shady land deals to incest, the key to Cross’ evil is his capacity to rationalize. Consider the way he hesitates at first when, like a spider approaching its prey, he tells his (grand)daughter Katherine (Belinda Palmer) that he’s her grandfather; he stutters, pauses to rationalize, and now certain he proceeds—“I am your grandfather.” Towne’s incest plot is meant to dramatize Cross’ rape of the land for the sake of “the future” in a grand symbolic expression. This comparatively smaller crime represents the degree to which his manipulation of public services is vile and unforgivably corrupt. But Cross’ is evil beyond political corruption or his incestuous transgressions—his evil is transcendent in that it justifies itself for a perceived better future. For Jake, Cross, too, personifies his Chinatown Syndrome, as the man remains immeasurably wicked, untouched by authorities, and wholly necessary for progress, which Jake’s transparent sense of justice cannot comprehend.

Polanski brilliantly orchestrates the picture’s final sequence, having spent months writing, rewriting, and planning before it was shot. Jake arranges for Evelyn and Katherine to get out of town to Mexico, away from Cross. In the meantime, they hide at Evelyn’s butler’s apartment in Chinatown, where Jake’s associates Walsh (Joe Mantell) and Duffy (Bruce Glover) meet to assist. Escobar believes Jake is withholding evidence to Hollis’ murder and extorting from Evelyn as an accessory after the fact; he handcuffs Jake and his associates. Cross is there too and wants to raise Katherine as his daughter. They all converge simultaneously at the same place in a climax neither contrived nor convenient. Cornered, Evelyn packs Katherine into her car and shoots the approaching Cross (who urges Evelyn to “be reasonable”) in the arm to keep him away. As she speeds away, the police call for a halt, but she does not stop, and they fire. The sound of the car horn reverberates through the streets; we can see it already—her dead body has fallen forward on the horn. Katherine screams. Everyone rushes down to the car. A bullet has penetrated the back of Evelyn’s head and escaped through her left eye. Katherine is carried away in Cross’ arms. Escobar orders everyone to be set free. By this moment, the audience has lost perspective on either the land conspiracy crime or Cross’ incest, and like the emasculated Jake, we are left helpless, floating in his Chinatown Syndrome to pick up the pieces. Escobar twists the knife: “You never learn, do you, Jake?” Jake’s associate Walsh resolves, “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” This iconic last line remains so tragic, as if Jake could ever forget.

Polanski and Towne labored to include visual cues and hints to imply Jake’s unseeing condition and further hint at Evelyn’s death, and effectively keep water “on the brain” as well. Throughout the picture, there are a series of binary lenses, lights, and glass objects found broken or made so by Jake’s interference, foretelling Evelyn’s eye being shot out: Jake sets down two pocket watches on either side of Hollis’ automobile tire to determine when his car leaves a water dumping ground, and afterward one is broken; one of the lenses in Jake’s sunglasses is broken by protective farmers when he’s caught snooping around an orange grove; before Jake follows Evelyn’s car, he shatters one of her brake lights so he won’t lose her in the night; later, Jake finds a pair of glasses in the Mulwray’s tide pool with one lens missing. There are just as many references to water or lack thereof: the drought in Los Angeles, Hollis drowning, Hollis standing at the ocean and row-boating with Katherine, Jake’s visit to the reservoir, the saltwater tide pool, the Albacore Club with its flying fish symbol and fish served head-on for lunch, and an exhaustive number of references to water in the dialogue. These broad-stroke citations barely begin to tap the intricate level of detail Polanski and Towne achieve in Chinatown, and to identify all of them would be missing the point.

Polanski and Towne labored to include visual cues and hints to imply Jake’s unseeing condition and further hint at Evelyn’s death, and effectively keep water “on the brain” as well. Throughout the picture, there are a series of binary lenses, lights, and glass objects found broken or made so by Jake’s interference, foretelling Evelyn’s eye being shot out: Jake sets down two pocket watches on either side of Hollis’ automobile tire to determine when his car leaves a water dumping ground, and afterward one is broken; one of the lenses in Jake’s sunglasses is broken by protective farmers when he’s caught snooping around an orange grove; before Jake follows Evelyn’s car, he shatters one of her brake lights so he won’t lose her in the night; later, Jake finds a pair of glasses in the Mulwray’s tide pool with one lens missing. There are just as many references to water or lack thereof: the drought in Los Angeles, Hollis drowning, Hollis standing at the ocean and row-boating with Katherine, Jake’s visit to the reservoir, the saltwater tide pool, the Albacore Club with its flying fish symbol and fish served head-on for lunch, and an exhaustive number of references to water in the dialogue. These broad-stroke citations barely begin to tap the intricate level of detail Polanski and Towne achieve in Chinatown, and to identify all of them would be missing the point.

Polanski wants his audience lost in a swell of momentary details and rendered incapable of seeing how they all fit together to engrain Jake’s subjectivity. Only when we become as lost in this Chinatown Syndrome as Jake can we identify with the profound sadness felt at the end of the picture, a sensation to which Polanski must have been able to identify. Polanski, too, could do nothing as powers outside of his control took away Sharon Tate. So the director, consciously or unconsciously, has a meaningful correlation with Jake Gittes—like Jake, he was a bystander incapable of stopping a senseless crime and protecting his love. Again we must reflect on how achingly overdue Walsh’s last line arrives, reminding Jake that he will never be cured of his syndrome. Towne intended Chinatown to bring a renewed awareness of the real-life disputes over water rights between the City of Los Angeles and farmers of Owens Valley. But just as the film’s water conspiracy overshadows the incest revelation, the film’s final message consecrates a notion that Jake’s worldview is not isolated and grim. He is either unwilling or incapable of accepting the world’s true form of intractable, perverse, yet essential corruption that drives the future but remains sheer madness.

Bibliography:

Cronin, Paul. Roman Polanski: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

Easton, Michael. Chinatown. B.F.I. Film Classics series. University of California Press, 1998.

Leaming, Barbara. Polanski, The Filmmaker as Voyeur: A Biography. Simon & Schuster, 1981.

Polanski, Roman. Roman by Polanski. Morrow, 1985.

Sandford, Christopher. Polanski: A Biography. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review