The Definitives

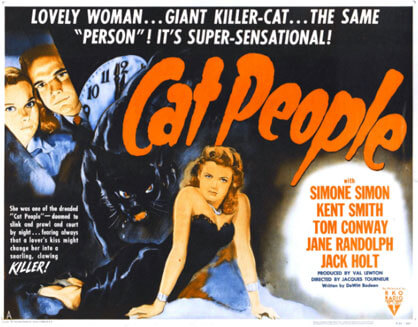

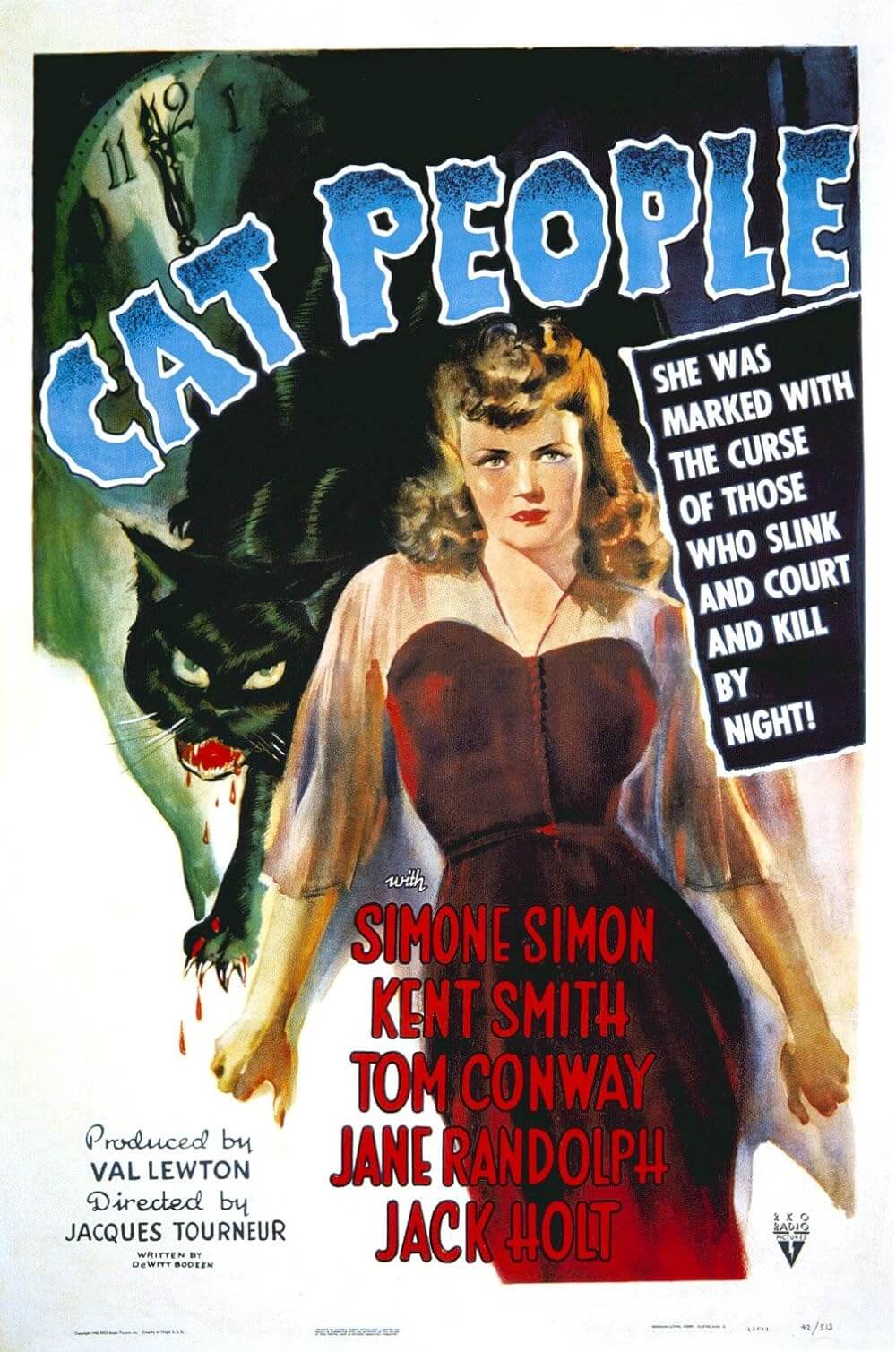

Cat People (1942)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Cat People’s most brilliant moments were born out of the necessity for inventive filmmaking. Legendary producer Val Lewton, whose short-lived career at RKO in the 1940s realized some of classic Hollywood’s most atmospheric and haunting pictures, had few resources with which to make his short run of horror films. Working with modest budgets, Lewton’s productions used economically convenient shadows and narrative ambiguity that created a richer, more involving experience for his audience. Lewton’s desire to elevate the low-budget “B” production resulted in literate, restrained films that explored the depths of the human psyche. None more so than this 1942 release, as evidenced by the film’s remarkable artistry; its themes of inwardness, alienation, and repressed desire; and its effective use of what the viewer does not see. Cat People remains a rare sort of film that demands close scrutiny, as its filmmakers have steeped the narrative and formal presentation with thematic symbolism and a rich emotional substance that parallel its psychologically complex heroine. To be sure, the surface text involves a predictable tale about a supernatural woman who shape-shifts into a large black panther, not unlike many cinematic were-monsters from the era. Still, the subtext has been loaded with sexual anxiety, displacement, and profound empathy for the demonized feminine identity at the film’s center. Lewton and his director Jacques Tourneur refuse to explain every detail or provide their audience with easy answers. Because of it, Cat People has continued to summon viewers back to its chimeric passages.

In the late 1930s through the 1950s, major studios designated most horror films as “B” productions. A standard Hollywood horror film boasted grotesque monsters, cobwebs, thunderclaps, a howling wolf in the distance, or a mad scientist’s laboratory to spook audiences, but no major star power. The Pre-Code era offered the most exciting, riskiest horror pictures: MGM’s Freaks and United Artists’ White Zombie both caused a stir in 1932. Universal Studios dominated the horror genre with a series of iconic, lucrative monsters, while other studios only dabbled in horror. Universal’s earliest efforts included The Werewolf (1913) and The White Wolf (1914), followed by “the man of a thousand faces” Lon Chaney appearing in The Phantom of the Opera (1925). With the advent of talkies, Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) and James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) arrived, making genre icons out of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, the latter of whom went on to appear in The Mummy (1932) and Whale’s campy The Bride of Frankenstein (1935). Lon Chaney, Jr. appeared in The Wolf Man (1941), the film that established werewolf lore such as the silver bullet and the werewolf’s bite that spreads the curse to its victim. Elsewhere, Paramount Pictures distributed The Cat and the Canary (1939) and the supernatural thriller The Uninvited (1942), while Warner Bros. explored macabre mysteries in Doctor X (1932) and Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933). Aside from a few exceptions, the classic Hollywood horror formula never attempted much more than sensationalism. Still, as today, audiences flocked to theaters to see the latest horror film, which meant studios could make them cheaply but still earn the profits of an “A” production.

Cat People remains an exception to the Hollywood rule. The film’s journey to the screen begins with RKO head Charles Koerner, whose studio was on the decline in the early 1940s. However, horror presented a low investment opportunity to lift RKO out of its slump. Koerner also wanted to try something unlike Universal’s inventory of monsters and mad-scientist creations. He wanted to develop a picture called “Cat People”—though he had only the title in mind and no inkling of what the film would be about. Koerner assigned the title to producer Val Lewton, the Russian-born mastermind whose career flourished between 1942 and his death in 1951. A former journalist and poet, Lewton had been adapting radio plays when David O. Selznick hired him as a writer and story editor. He served eight years under the despotic Selznick and doctored scripts, uncredited, before finally securing a position at RKO over a small production unit. Lewton also convinced a research assistant named DeWitt Bodeen to leave Selznick’s employ and join him at RKO as a writer. Their first project was Koerner’s “Cat People” idea, a title Lewton thought was ridiculous but faced as a challenge from his new boss. Feeling stuck with a silly title, Lewton nonetheless wanted to avoid the typical lowbrow tricks associated with the horror genre; he wanted to do something artful and emotionally resonant. He hired Jacques Tourneur to direct—together, Lewton, Bodeen, and Tourneur had carried out the second-unit sequences in Selznick’s A Tale of Two Cities (1935)—and they set out to make Cat People a reality. They were unsure of where to start but certain in their attempt to elevate horror into the realm of good taste.

Lewton and Bodeen started researching the feline in mythology and literature. They also watched several horror films from the era, among them Universal’s The Wolf Man and Erle C. Kenton’s Island of Lost Souls (1932), an adaptation of H.G. Welles’ The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) that advertised its primary attraction as follows: “The Panther Woman lured men on—only to destroy them body and soul!” From their research, they settled on adapting an Algernon Blackwood short story called “Ancient Sorceries,” first published in 1906, about a medieval French village populated by satanic cat people. But after a sleepless night, Lewton changed his mind and decided to tell a story in contemporary New York—which would be a bold contrast to the typical period pieces of the modern horror film. Still, the roots of Blackwood’s text remain in the script, which, credited to Bodeen, was by all accounts a group effort between Bodeen, Lewton, and Tourneur. Lewton had conceived the basic story, and together the group wrote the screenplay. No matter what the working collaboration may have been like, Lewton always took the day’s work home with him at night to rewrite everything the three had compiled during the day. Lewton was no director. But in a sense, taking a cue from Selznick, he pre-directed his films on the written page by incorporating detailed notes on how Cat People should look and feel. But Lewton did not accept screen credit as a writer until years later, under the pseudonym Carlos Keith, on The Body Snatcher (1945) and Bedlam (1946).

For his cast, Lewton wanted Simone Simon to play the feline-centric character of the film’s title, having seen the Franco-Italian actress in William Dieterle’s The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941) and, perhaps, Jean Renoir’s La Bête humaine (1938). Her catlike eyes, European tendencies, and meow-like accent suggest a pointedly exotic, foreign, and enigmatic feline woman. Secondary studio players like Kent Smith—whose line readings are consistently, and possibly intentionally, hammy—and Jane Randolph were cast in the other key roles, keeping production costs low. Shot between July 28 and August 21 of 1942, Lewton’s team finished production ahead of schedule and under budget, at $134,000. The entire production was filmed on soundstages, many of them repurposed sets from earlier productions. The lavish staircase in the heroine’s apartment building was a leftover from Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons (1942); the park and zoo sets were still standing after several Astaire-Rogers musicals; a ship and barge drafting workshop was rebuilt from the set of The Devil and Miss Jones (1941). Cat People required no monster transformations or elaborate special FX either. “We tossed away the horror formula right from the beginning,” Lewton told the Los Angeles Times. “No grisly stuff for us. No mask-like faces hardly human, with gnashing teeth and hair standing on end. No creaky physical manifestations. No horror piled on horror.”

The literary complexity of Lewton’s characters and their psychology in Cat People reflects his standing as an author (he wrote nine novels before committing to Hollywood) and rare status as a producer-auteur. As a result, the film cannot be read like a typical film; rather, it must be assessed in novelistic terms, with a close reading of its story and character dynamics. Cat People centers on Irena Dubrovna (Simon), a Serbian artist exiled to New York after a Nazi invasion of her homeland. She is haunted by legends, mere impressions, or maybe even memories of her supernatural ancestry. As Irena explains, she descends from a devil-worshipping cult in the Serbian mountains, an originally Christian people that turned to witchcraft after being enslaved by Mameluks. When King John of Serbia cleared the region, he killed the corrupted villagers alongside the Mameluks, and only a few of the “wisest and most wicked” folk escaped his slaughter. As the myth of Irena’s people suggests, when aroused by passion, jealousy, or anger, she will transform into a black panther, a cat person. Irena’s sense of ill-fated monstrosity finds her sketching in the film’s first scenes. She draws images of a panther impaled by a spear at the Central Park Zoo, where she meets an optimistic American suitor, Oliver (Kent Smith), affectionately called “Ollie.” When she explains her ancestral anxieties to Ollie, she seems to assign him the role of King John in hopes that he will conquer her inner beast. Bravely and stupidly taking on the role, he assures her: “You’re so normal you’re going to marry me, and those fairy tales, you can tell ‘em to our children.” But weeks after their hasty wedding, the marriage remains unconsummated, as Irena continues to fear what she may become.

Irena experiences crippling sexual anxiety, fear of intimacy, and a genuine terror of the supernatural forces—the evil—that she believes inhabit her and will emerge if she satisfies her urges. Part of her yearns to be intimate. When Ollie first walks Irena home, she beats him to the punch and invites him up to her apartment for tea. “Oh, Miss Dubrovna, you make life so simple,” he quips. A moment later, at her door, she admits, with an aching vulnerability, “I’ve never had anyone here […] you might be my first real friend.” Inside, her perfume fills the air with “something warm, living,” Ollie observes. As the night grows dark, Irena looks out the window and says, “I like the dark. It’s friendly.” Their mutual place in the darkness suggests their doomed love and everything that remains unspoken about their forthcoming marriage, from Ollie’s apparent love for his fellow ship and barge designer, Alice (Randolph)—a comparatively normal, “good egg”—to Irena’s lingering self-doubt and fear of intimacy. On their wedding night, Irena rebuffs her new husband, saying, “Be kind, be patient. Let me have some time, time to get over that feeling there’s something evil in me.” Ollie kindly sleeps on the couch while, in the bedroom, Irena scratches at the door, filled with desire yet terrified at what her yearnings may unleash. Just as Cat People portrays sexual repression, the film implies the struggles of a failing marriage built on superficial terms. Ollie’s affection for Irena seems to be based on his erotic curiosity about her unusual foreignness—a stark contrast to the film’s other woman, Alice—and his desire to overcome her internal reservations with his “Americano” certainty.

In many ways, Cat People provides a female response or alternative to The Wolf Man. Colloquial symbolism associates men with wolves and women with cats, and Lewton seems to use this to create the inverse of several elements from The Wolf Man, including character, setting, and narrative. Lon Chaney, Jr.’s Larry Talbot in The Wolf Man returns to his old-world European village from America and, after being attacked, turns into a werewolf until finally he’s killed by his father’s silver-headed cane. The basic concept finds a modern American man cured by ancient mysticism. The opposite is true of Irena in Cat People. She’s a European woman in a modern American setting trying to shed her innate old-world origins but cannot. She achingly resists turning into a panther, which represents a transformation that brings her closer to her true, unrepressed form. By contrast, the werewolf acts like a disease thrust upon Talbot, taking him further away from his natural state. Additionally, the wolf has long been a symbol of unhinged sexuality and adulterous behavior, whereas Cat People shapes its own associations with the black panther as a symbol of Irena’s caged sexuality. When Irena visits the caged black panther at the Zoo, a zookeeper (Alex Craig) tells her, “No one comes to him when they’re happy. The monkey house and the aviary get all the happy customers.” The black panther, pacing behind its bars at the Zoo, becomes a symbol for Irena’s feelings of sadness, despair, cultural imprisonment, and sexual repression.

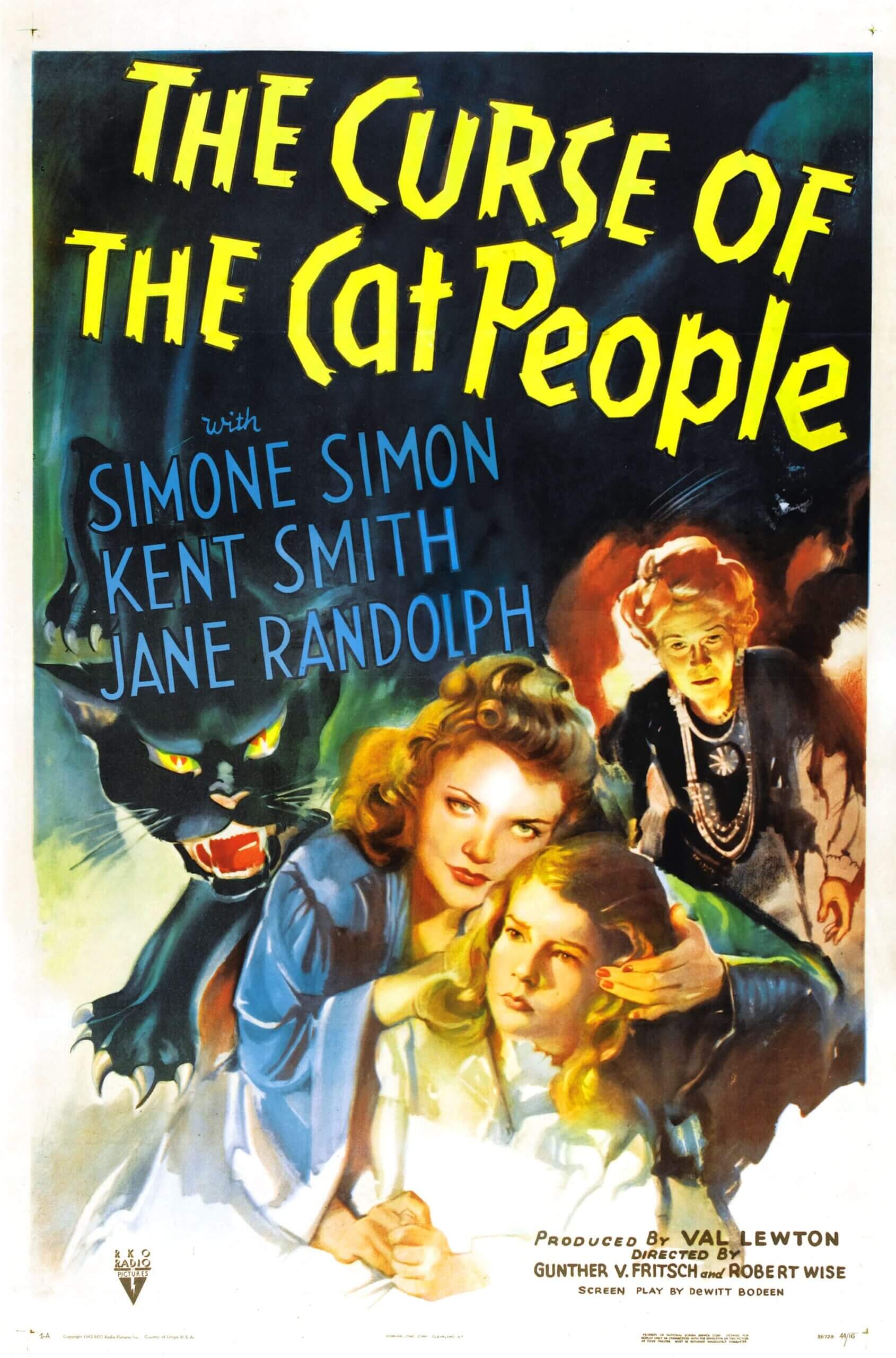

By extension, the cat people of the film’s title have their own connotations with animalistic human desire and unbridled lust. During Irena and Ollie’s small wedding party at a Serbian restaurant, she locks eyes with a mysterious woman (Elizabeth Russell). “Looks like a cat!” says one guest. Indeed, the Cat Woman approaches Irena and says, “Moia sestra, moia sestra?”—calling Irena “sister,” as if trying to confirm whether Irena is a cat person. The woman reminds Irena of her anxieties, suggesting her people’s mythological past may have a place in reality. The Cat Woman does not appear again in the film, but her brief, evocative appearance is felt throughout the subsequent scenes of Irena’s melancholy—her sexual resistance to Ollie and repeated visits to the panther at the Central Park Zoo. Then again, several film scholars have suggested that the Cat Woman’s use of the word “sister” infers a lesbian association between them, and that Irena’s later fear of intimacy results from being uncertain of her sexual attraction to a male. Certainly, Cat People’s ambiguity could be seen as coded with a queer subtext, but Lewton intended no such meaning. Rather, “sister” undoubtedly refers to the Cat Woman recognizing either a fellow countrywoman or a fellow cat person; though, neither the original film nor its sequel, The Curse of the Cat People (1944), ever address the character again.

Cat People becomes an unconventional love triangle when Ollie seeks consolation with Alice. Alice describes herself as “a new type of other woman,” and her character couldn’t be more correct. In classic Hollywood, the traditional other woman, often in film noirs, was usually a vampish sexpot that offered the male protagonist something he could not find in his comparatively plain, nagging, or just-plain-dull steady. Depending on one’s perspective, the opposite may be true of Alice in Cat People, an uncharacteristic other woman who also happens to be an average girl-next-door, someone to whom Ollie can speak openly. But Alice may be the other woman only because the film opens where it does, with Ollie picking up Irena at the Zoo. In the same scene, we barely notice Ollie’s blonde date, seen only from behind. This is likely Alice. And from Alice’s point of view, Irena is the vampish other woman seducing her would-be beau; she simply failed to articulate her love for Ollie earlier, and now he’s married, and she must win him back. Moreover, Alice’s down-to-earth alternative seems more appropriate for the leading man given the marriage troubles between Irena and Ollie from the outset, if for no other reason than the reaction from the small kitten Ollie buys his new wife.

The kitten is the first inkling that something may be legitimately wrong with Irena, that her stories may be true. Ollie keeps the kitten in a miserable, entirely too small box punched with air holes at his office desk. When it emerges, much to Alice’s delight, the kitten purrs in her arms. But later, when Ollie brings it home for Irena, the kitten recoils and hisses. They resolve to return the kitten to the pet shop in exchange for something else. Once they enter the shop, nearly every animal goes wild, panicking from Irena’s presence. “Animals are ever so psychic,” says the pet shop owner. “They seem to know who’s not right.” While Irena waits outside, shielding herself from the rain under an umbrella, Ollie settles on a bird. They set up a small cage in Irena’s apartment. One day, Irena tries to grab it. She paws at the frightened bird, the creature leaping in its cage away from Irena’s hand. A glint appears in Irena’s eye and a disturbing smile on her face. Anyone who has ever owned a cat recognizes that look of horrible joy in the torture of another animal. For a moment, Irena delights in the bird’s fear. But when the bird dies out of terror, she feels horrible and ashamed—the scene has only added to her feelings of self-doubt—yet she also feels compelled to feed her dead pet to the panther at the Zoo. And while this development could have turned Irena into a monster in the audience’s eyes, the film maintains our sympathy for her, and her digression into a cat person becomes increasingly tragic.

Worried about Irena’s mental state, Ollie and Irena agree she should meet with a psychiatrist. Curiously enough, Alice recommends Dr. Louis Judd (Lewton regular Tom Conway) to Ollie for Irena, well aware of the way “he goes about kissing hands.” Did she hope Dr. Judd would seduce Irena, leaving Ollie available? In any case, the psychiatrist was a regular fixture in the Freud-fanatic Hollywood of the 1940s, serving as a device to explain away bizarre phenomena using semi-authentic psychobabble. After being subjected to hypnosis, Irena explains her preoccupations and worries to Dr. Judd, who assures her, “These things are very simple to psychiatrists.” He explains that her worries about transforming into a cat person result from her lack of a father and victimization through bullying as a child. These emotional scars led to unresolved psychological damage, which he promises to clear up. But Lewton treats Dr. Judd and his scientific explanations as a false certainty. The character provides a clear hypothesis for Irena’s condition to the audience, explaining away the film’s events as the symptoms of a troubled mind. Lewton uses Dr. Judd’s credible psychiatric assuredness to establish doubt in the film’s supernatural circumstances. Once the audience believes in the logical explanation, it makes the illogical and fantastical explanation all the more shocking in its short, momentary images that align with Lewton’s philosophy toward horror: “You can’t keep up horror that’s long sustained. It becomes something to laugh at. But take a sweet love story, a story of sexual antagonisms […] and you’ve got something.”

Cat People soon shifts from a film about Irena’s unease over her animal nature to a film driven, in part, by jealousy and the menacing threat of death. When Irena returns home from seeing Dr. Judd, it’s apparent that Ollie and Alice have been discussing her therapy session. Although Ollie assures her that Alice understands, Irena becomes jealous: “There are some things a woman doesn’t want other women to understand.” Irena is divided by a constant state of uncertainty about herself: her panther side wants to hunt Alice through the rest of the film out of suspicion, while her human side has a conscience, as well as a desire to kill herself if the stories about her people prove true—she’s still uncertain about herself, after all. She repeatedly visits the Zoo’s black panther, a creature the zookeeper equates to a demonic melanistic leopard from the Book of Revelation. But in all his distracted talk, the zookeeper leaves the key to the panther cage in the lock. Irena takes it, perhaps planning to use the panther—an animal Dr. Judd calls an “instrument of death.” After their fight about Alice, Irena returns home to Ollie with an appeal, or maybe it’s a warning: “We should never quarrel, never let me feel jealousy or anger. Whatever it is that’s in me is held in, is kept harmless, when I’m happy.” Regardless, Cat People‘s love triangle begins to alter its shape in Alice’s favor: she admits to loving Ollie, and he admits to being unsure if he loves his wife.

Meanwhile, Irena’s suspicion grows after Ollie lies (“I’ve got some work to do”), and then he meets up with Alice. Only in her jealousy and cat person rage does Irena feel sure of herself, and she focuses that composure on Alice. She follows from the shadows as her husband walks the other woman home. A sudden chill comes over Alice, who sets out from Ollie and heads through the park alone. Close shots of Alice’s heels clicking on the sidewalk are intercut with Irena in pursuit, the distant sound of footsteps behind Alice getting faster and faster. Alice stops, and so do the footsteps following her. She knows someone is there, watching her. The scene is hushed. Suspense builds. We see Alice in a medium shot. All at once, a bus ruptures the silence by jolting into the frame from the right, between the camera and Alice, its brakes hissing. Our hearts almost stop. “You look as though you’d seen a ghost,” says the driver, diffusing the tension with his unconcerned demeanor. The scene demonstrates how much terror Lewton and Tourneur could squeeze out of a tense situation without showing the audience anything except shadows. Ever since, the term “buses” has been used to describe a scene in which something passes in the foreground with an unexpected aural blast that startles the viewer. “Buses” have been a common tool still employed by contemporary horror filmmakers such as John Carpenter and James Wan. Today, we know them better as jump scares.

In the next shot, the camera settles on a zookeeper who finds several slaughtered sheep. The zookeeper’s lantern illuminates the sidewalk, where a long take follows bloody paw prints and their gradual transformation into the impressions of high-heeled shoes. In addition to confirming that Irena’s anxieties are justified, the shot suggests Irena’s metamorphosis is somehow less a physical, clothes-tearing change (like most cinematic werewolves) than one impelled by witchcraft, making her clothes part of her enchanted transition. When the camera finds Irena again, she dabs the corners of her mouth with a handkerchief, and the implication of her transition is complete. When Irena gets back home, she locks herself in the bathroom, soaks in a bath, and cries, realizing what before she had only feared—she is a cat person. That night, she has a twisted nightmare about unlocking the panther cage at the Zoo. Her terror over the dream begs the question: Did the panther dream frighten her because she fears what she may become again, or because she knows unleashing the Zoo’s panther could mean her death? She tries to continue as normal the next day, but Ollie’s inconsiderate behavior isolates her. When they visit a local museum, he invites Alice to look at ship paintings and models, and Irena becomes the third wheel. Angered about their museum visit, Irena stalks Alice back to her home at the YWCA. Alice has decided to take a late-night swim, and one of the receptionist’s (Betty Roadman) kittens follows her.

In the next shot, the camera settles on a zookeeper who finds several slaughtered sheep. The zookeeper’s lantern illuminates the sidewalk, where a long take follows bloody paw prints and their gradual transformation into the impressions of high-heeled shoes. In addition to confirming that Irena’s anxieties are justified, the shot suggests Irena’s metamorphosis is somehow less a physical, clothes-tearing change (like most cinematic werewolves) than one impelled by witchcraft, making her clothes part of her enchanted transition. When the camera finds Irena again, she dabs the corners of her mouth with a handkerchief, and the implication of her transition is complete. When Irena gets back home, she locks herself in the bathroom, soaks in a bath, and cries, realizing what before she had only feared—she is a cat person. That night, she has a twisted nightmare about unlocking the panther cage at the Zoo. Her terror over the dream begs the question: Did the panther dream frighten her because she fears what she may become again, or because she knows unleashing the Zoo’s panther could mean her death? She tries to continue as normal the next day, but Ollie’s inconsiderate behavior isolates her. When they visit a local museum, he invites Alice to look at ship paintings and models, and Irena becomes the third wheel. Angered about their museum visit, Irena stalks Alice back to her home at the YWCA. Alice has decided to take a late-night swim, and one of the receptionist’s (Betty Roadman) kittens follows her.

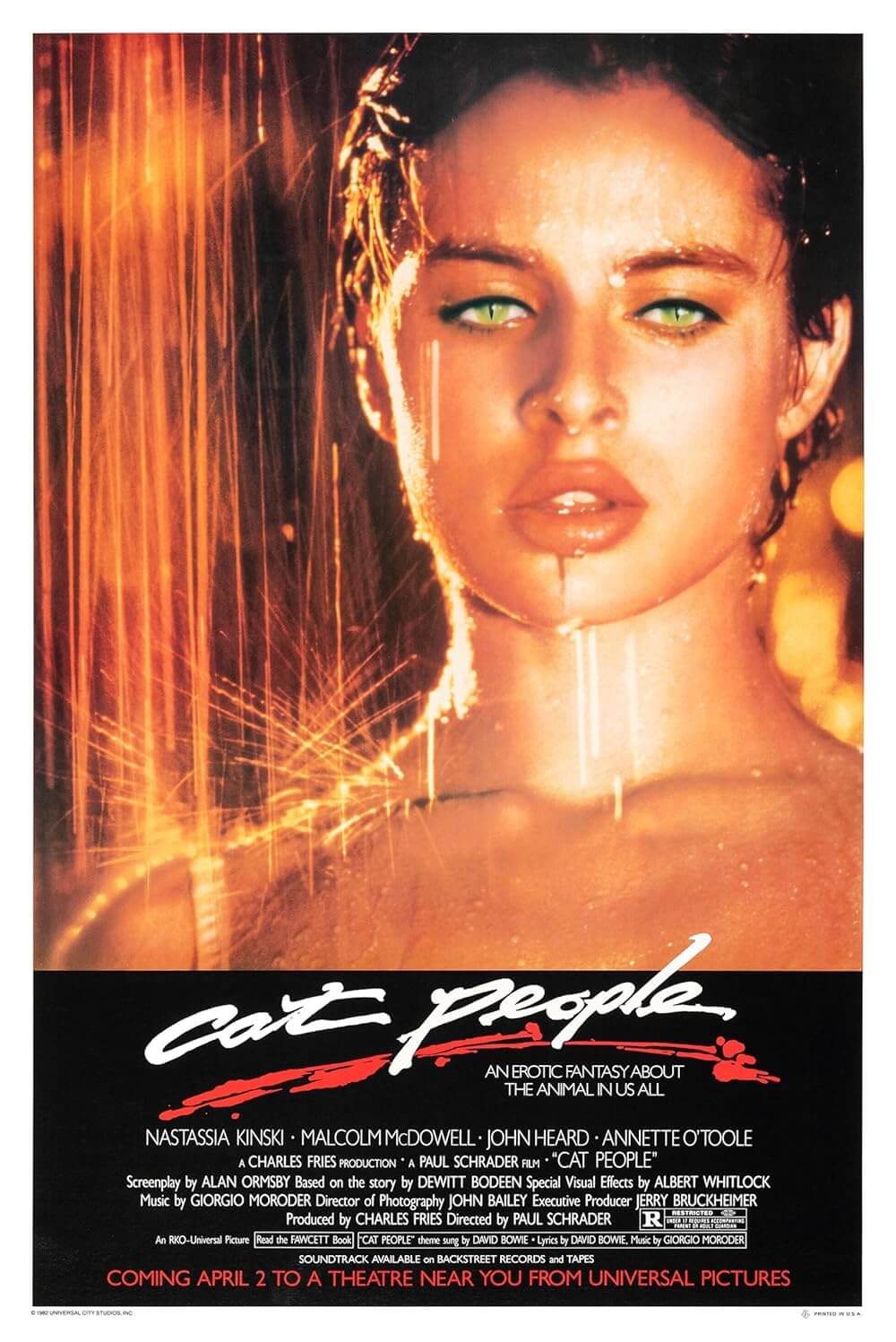

Although the cliché of a vulnerable woman in water—like Marion showering in Psycho (1960) or Nancy bathing in A Nightmare on Elm Street (1983)—has grown tired today, its use in Cat People remains a superbly crafted set-piece. Additionally, due to the limitations of the period, the scene avoids exploiting its vulnerable female through nudity, and therein feels more tasteful than later examples (most notably in Paul Schrader’s remake, where Alice swims topless). As Alice changes into her bathing suit, the kitten follows her into the pool area. The film has already established that cats prefer Alice to Irena, and so when the kitten begins to hiss and arch its back, both Alice and the viewer know something is wrong. Shadows created by the pool lights cast uncanny reflective webs on the walls and ceiling, and every sound echoes the pool’s emptiness and Alice’s isolation. Alice begins to hear deep growling from the stairway and, thinking of the night before, leaps into the pool for safety. She treads water and listens to the snarling panther noises until she sees a shadow reflected on the wall. Alice screams—perhaps cinema’s most reverberating, desperate, and phantasmal scream—and the YWCA receptionist rushes to investigate. Irena turns on the light. She stands composed, in a power position over Alice, deliciously confident in her sexuality, and explains that she’s looking for her husband after being separated at the museum. “You’ll probably find him at home,” Alice says, both women pretending that what just happened didn’t just happen. Now Alice trembles in Irena’s presence, and Irena begins to feel more poised in her dual animal-human transitions. After Irena leaves, the receptionist finds Alice’s robe in shreds on the ground. “Gee whiz, honey. It’s torn to ribbons.”

After Irena’s behavior in the pool, Alice becomes convinced that Irena’s beliefs may be more than just a delusion. She conspires with Dr. Judd and Ollie (who has resolved to leave his wife) to put Irena into an institution. Dr. Judd explains that Ollie cannot divorce his wife after she’s been committed, but everyone agrees that Irena’s committal is the best course of action. That night, when Irena fails to come home, Alice and Ollie decide to catch up on some shipping designs at work. But they soon discover they have been locked inside the office with Irena—now a snarling black panther that corners them. Ollie grabs a nearby drafting tool, the crucifix-like T-square, and shouts, “Leave us, Irena, in the name of God, leave us in peace!” The panther rushes off, leaving behind the scent of Irena’s perfume. Back in Irena’s apartment, Dr. Judd greets Irena as she arrives home. Still unconvinced of her supernatural claims, he offers to comfort her professionally and romantically (he has made subtle passes at Irena, even in their therapy sessions). He kisses her, unleashing the beast that Irena has feared all this time. She transforms, and, finally, Dr. Judd sees that her stories were true. She kills him, but not before being impaled by Dr. Judd’s concealed cane-sword. In the final moments, Irena returns to the Zoo to unlock the black panther—an act both symbolic and suicidal. At first, the animal hesitates but then lashes out at Irena to escape, scaling the Zoo wall and meeting its death under a car. Ollie and Alice find Irena dead, in part from Dr. Judd’s sword, in part from the panther. “She never lied to us,” Ollie remarks over her body.

The final line signals the tragic conclusion to Cat People, Lewton’s sad tale about an outsider torn between her instincts and her conscience. Irena seems to have struggled with her origins long before Ollie arrived. She says that she never wanted to love anyone: “I’ve stayed away from people. I lived alone. I’ve fled from the past, some things you could never know or understand. Evil things, evil.” Dr. Judd explains Irena’s story is a “byproduct of her fear” and tries to find a logical explanation; like Ollie, he suffers from The White Knight syndrome in his need to rescue vulnerable women. And as much as Irena wants to be rescued, she does not need to be, or perhaps cannot be. Her inability to escape her fate and her unavoidable transformation into a monster should someone attempt to love her turns Irena’s story into a tragedy. Whether or not her monsters are real has been a debated issue among film scholars. Much like The Wolf Man, which I have argued elsewhere is a film not about a metamorphosing monster but an everyday psychopath who believes himself to be a monster, Cat People could be read as an allegory for the female la bête humaine. Certain horror scenes in the film could be explained away in purely psychological terms or by suggesting that Lewton and Tourneur meant the scene metaphorically. Other moments are irrefutable, such as the dead sheep, transforming footprints, shredded robe, and Ollie’s last line.

The final line signals the tragic conclusion to Cat People, Lewton’s sad tale about an outsider torn between her instincts and her conscience. Irena seems to have struggled with her origins long before Ollie arrived. She says that she never wanted to love anyone: “I’ve stayed away from people. I lived alone. I’ve fled from the past, some things you could never know or understand. Evil things, evil.” Dr. Judd explains Irena’s story is a “byproduct of her fear” and tries to find a logical explanation; like Ollie, he suffers from The White Knight syndrome in his need to rescue vulnerable women. And as much as Irena wants to be rescued, she does not need to be, or perhaps cannot be. Her inability to escape her fate and her unavoidable transformation into a monster should someone attempt to love her turns Irena’s story into a tragedy. Whether or not her monsters are real has been a debated issue among film scholars. Much like The Wolf Man, which I have argued elsewhere is a film not about a metamorphosing monster but an everyday psychopath who believes himself to be a monster, Cat People could be read as an allegory for the female la bête humaine. Certain horror scenes in the film could be explained away in purely psychological terms or by suggesting that Lewton and Tourneur meant the scene metaphorically. Other moments are irrefutable, such as the dead sheep, transforming footprints, shredded robe, and Ollie’s last line.

Cat People’s visual style reflects not only Irena’s unease with her looming internal monster, but also her sexuality, psychological state, and status as an immigrant in America. In each case, Irena presents an Otherness next to the all-American, well-adjusted Ollie and Alice—and, in a single, brief scene, Ollie and Alice’s chummy friends and coworker demonstrate that not every corner of Cat People’s world has been infected by the mysticism surrounding Irena. Despite being the film’s tragic heroine, Irena represents a series of contrasts with the American characters. Simon is exotic, speaks with a thick accent, and her character admits that she is not normal—but she desires to become a “normal, happy” wife. She also marks the only source of sexuality in the film, like a black hole, drawing men to her with an irresistible gravity. By contrast, Alice has a de-sexualized quality of a tomboy. Of course, the question of Irena’s status as an animal or monster separates her from the other characters as well, while the film maintains the perspective of masculine trepidation over the powerful, sexually confident female that Irena becomes in her cat person state. The Otherness of the cat people is tantamount to the Otherness of women in the film, often demonstrated by shadows.

Cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca used strong light sources positioned at low angles to make the most of the production’s modest, often repurposed sets. Musuraca employs chiaroscuro darkness throughout to light the film’s characters in unconventional ways. Cat People is a film that feels off-kilter, often because the light sources come from the ground, projecting shadows onto otherwise blank background walls. Though the sets and rooms photographed throughout the film may have few ornamentations, staircases, the characters in the foreground, or other objects in the room often create the visual atmosphere by the shadows they create. Note the spectral lighting in the YWCA pool and how the water reflects strange patterns throughout the room, as if the walls and ceiling themselves were writhing in the darkness. Or look at how the low glow of Alice and Ollie’s drafting table shines upward, illuminating their faces from below in an uncommon, eerie lighting style for any Hollywood production. Whenever Irena is near, either in human or panther form, the lighting seems to dim, and shadows become Musuraca’s primary tool, leading to several lighting effects that give everything in Irena’s presence an unsettling appearance. But if Cat People had a larger budget and more resources, Musuraca’s innovations may not have been necessary.

When the film opened on Friday the 13th, 1942, the reviews were mostly lukewarm, if not dismissive, and certainly did not anticipate the audience’s lasting interest. As Lewton biographer, Joel E. Siegel noted, “The film that theatre bookers had expected would run no longer than a few days was held over week after week. It played so long at the Rialto that several newspaper reviewers went back for a second, more favourable look.” The film grossed around $3 million on its meager budget, cementing Lewton’s place at RKO. He went on to produce four more titles in 1943 alone, including I Walked with a Zombie, The Leopard Man, The Seventh Victim, and The Ghost Ship, the former two directed by Tourneur, who later moved to more prestigious fare at RKO, such as Out of the Past (1947) and Easy Living (1949). Despite his profitable and creative successes, RKO wanted a sequel to Cat People. An editor named Robert Wise was hired to make his debut directing Lewton’s The Curse of the Cat People in 1944. Wise would helm two more horror pictures for Lewton before going on to a career-making The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), West Side Story (1961), The Haunting (1963), and The Sound of Music (1965). And while Lewton had ambitions to escape the horror genre into more prestigious fare, he maintained the most control over his “B” productions—the films that secured his legacy.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Lewton described his approach in each of his films, beginning with Cat People: “A love story, three scenes of suggested horror and one of actual violence. Fade out. It’s all over in less than seventy minutes.” But Lewton gives himself far less credit than he deserves. In Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), Kirk Douglas plays a “B” filmmaker, a fictionalized version of Lewton named Jonathan Shields. His character has been assigned to make “The Doom of the Cat Men,” and being unconvinced by his production’s cheap guy-in-a-suit costumes, he says, “What scares the human race more than any other thing? The dark. Why? Because the dark has a life of its own. In the dark, all sorts of things come alive. Suppose we never do show the cat man. Now what we put on the screen will make the backs of their necks crawl.” With meager financing and lofty ambitions, Lewton and Tourneur were limited in what they could show, and show well, and were therefore forced to experiment. Today’s filmmakers rely on CGI to render anything imaginable onto the screen. They have the limitless power to create, and so they have no reason to hide even the most outlandish moments in atmospherics. At the same time, audiences do not need to use their imaginations when screening the latest supernatural haunter or intergalactic superhero blockbuster—it’s all right there on the screen. But necessity breeds creativity.

Cat People became more expressive in its visual and narrative symbolism because of a budgetary need, forcing Lewton to rely on imagination and technical innovation to tell his story. Lewton had to innovate and work within restrictions, which created more artistic choices and a concentration on complicated human relationships. Given the extensive reading of the narrative above, it is important to remember that such complex storytelling takes place over just a 72-minute runtime. Lewton and Tourneur’s dazzling work, particularly on Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie, relies on the audience’s imagination, a rare notion that what the viewer doesn’t see is just as important as what appears onscreen. Beyond any discussion of what is shown and not shown, Lewton, as a producer-auteur, explored similar themes of darkness and misery throughout his short career. He often traced the journey of young, female characters into a realm of self-understanding. Like Irena, Lewton’s characters feared what lies in the darkness and set out to demystify it; however, their journey often ended with their fears justified, revealing a sinister reality about the unforgiving world.

If Cat People is, then, unlike other horror pictures of its time, it is not because low-budget horror films were only being made by a limited number of filmmakers. Quite the opposite. The film remains exceptional because Lewton demanded its artistry and themes move away from what audiences were accustomed to seeing. In doing so, Lewton made the first supernatural horror story set in modern times, typifying a standard formula for today’s paranormal horror genre: it’s a real-world story whose characters have complex relationships, maintain unglamorous careers, and remain skeptical toward the prospect of anything fantastical. Irena’s internal conflict begins as psychological, crippling her with feelings of sexual anxiety, emotional vulnerability, and a sense of isolation. Irena’s transformation remains tragic for how it allows her to move beyond inner preoccupations, yet also transforms her into a beast. With a taste for the macabre and melancholy, Lewton’s cultured and psychologically intricate films would eschew the cheap gimmicks of standard horror films—or at least shroud them in atmosphere and deeper regard for characters. Rather than jolt his audience by visualizing grotesque monsters onto the screen, he relied on his audience to imagine a terrifying scene in their minds and identify with the human drama on the screen. Cat People leaves us with much to consider about its heroine, use of darkness and the unconscious, and the inward feelings that have haunted audiences since its release.

Bibliography:

Bansak, Edmund G. Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career. McFarland, 1995.

Hantke, Steffen, editor. Horror Film: Creating and Marketing Fear. University Press of Mississippi, 2004.

Jewell, Richard B. The Golden Age of Cinema: Hollywood 1925-1945. Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Newman, Kim. Cat People. 2nd Ed. British Film Insititute, 2013.

Siegel, Joel E. Val Lewton: The Reality of Terror. Secker and Warburg, 1972.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review