The Definitives

Casablanca (1942)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

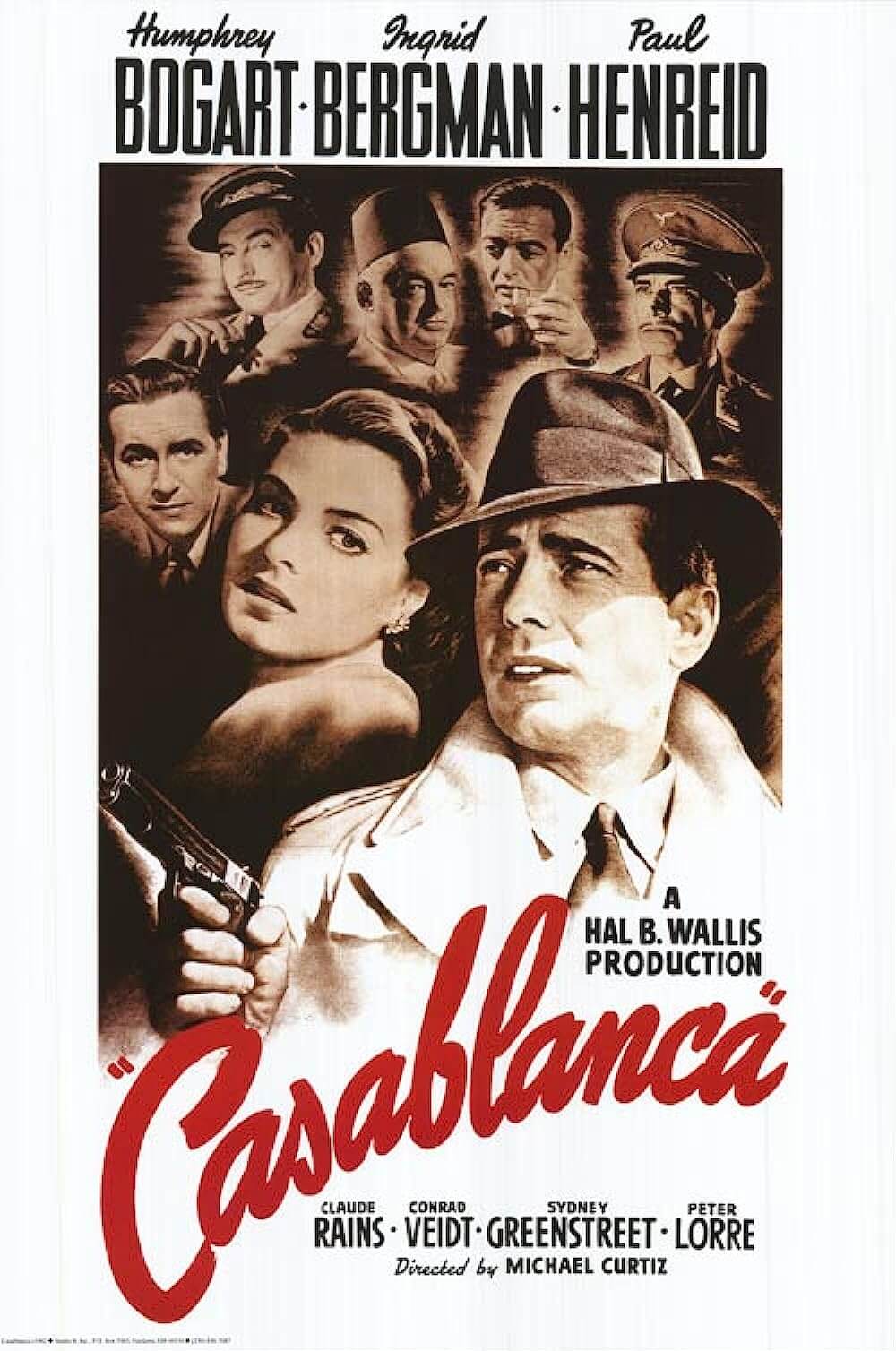

Movie Magic, however conceptual a notion, offers an understanding of how motion pictures converge from multiple points of artistic influence under the sometimes chaotic circumstances of their creation. Filmmaking remains one of the only collaborative artform where artists group together and combine their efforts to construct a single product. And though the director oftentimes receives sole credit for the final result of a film, the cast and crew contribute their individual influence into the harmonious gathering of technical and narrative composition. Casablanca is perhaps the most memorable film that, given its infamously frenzied production and now iconic status in the annals of film history and popular culture, fulfills all the possibilities inherent to Movie Magic. Made to be another cookie-cutter product of The Dream Factory, the production amassed top Warner Bros. talent working from a script that had no ending. That the film was ever completed is miraculous; writers rushed fresh pages to the set on the day they were being shot, while actors performed without knowing their motivations. But any number of Hollywood films released during The Golden Age, an era whose arguable timeline exists from the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s, were assembled under similar conditions. And yet, only the timeless Casablanca has surpassed all precincts of era and story to gain status over the years, increase in popularity and enjoyment, and still inspire wonder even upon close reexamination.

Writing about the film today can serve only to retread or flesh-out the scores of exhaustive studies currently available, because, unanimous throughout the writings on Casablanca is the bewilderment for how it came together. Much has been made of the bizarrely efficient disorganization that uniquely helped some of the picture’s greatest moments retain their historic place. No matter how accomplished the scholar or enthusiast examining the picture, none of them pinpoint exactly why the film turned out so well, if in fact there is any reasoning behind it besides pure luck. Their analyses chart the progress of happenstance and twists of fate, arousing equally appropriate amazement and bafflement. Anecdotes are told on how various scenes came this close to being something completely different, and occasional attributions are given to producer Hal B. Wallis, director Michael Curtiz, the many writers, or the undeniable charisma of the actors. What slowly emerges from the assorted investigations is an understanding that by some marvel Casablanca became the film we know and love today.

And what a phenomenon, in particular when reflecting on how today’s filmmakers and mega-conglomerate studios would react to such on-set commotion. Imagine if Casablanca were made in a contemporary market, with today’s entertainment media scrutinizing behind-the-scenes mishaps, general last-minute decision making, and studios unwilling to lose the millions dumped into A-list stars and special effects. A wave of negative buzz would infect any chance of artistic or commercial success, as a modern studio would no doubt attempt to counteract the bad press with reshoots stemming from executive intervention and prescreening surveys, thus leaving the end result an unfocused mishmash, like so many current Hollywood films prove to be. Instead, the protective net of expert, precise studio era filmmaking supported the process under the required organization and supervision mandated by Warner Bros., the progenitors of Casablanca.

And what a phenomenon, in particular when reflecting on how today’s filmmakers and mega-conglomerate studios would react to such on-set commotion. Imagine if Casablanca were made in a contemporary market, with today’s entertainment media scrutinizing behind-the-scenes mishaps, general last-minute decision making, and studios unwilling to lose the millions dumped into A-list stars and special effects. A wave of negative buzz would infect any chance of artistic or commercial success, as a modern studio would no doubt attempt to counteract the bad press with reshoots stemming from executive intervention and prescreening surveys, thus leaving the end result an unfocused mishmash, like so many current Hollywood films prove to be. Instead, the protective net of expert, precise studio era filmmaking supported the process under the required organization and supervision mandated by Warner Bros., the progenitors of Casablanca.

Studios during The Golden Age churned out films according to an unyielding program wherein talent such as stars and technicians were contracted and paid according to a salary instead of per film, and motion pictures were released into theaters the studios owned. This scheme condensed the entire artform into a business aiming for demographic-free moviemaking bent on appealing to the most people and selling as many tickets as possible at the lowest cost. And within these boundaries, the quality of the products released was occasionally sacrificed for the sake of manufacturing efficiently. For a director to have Final Cut was unheard of. Films were a product of The Studio, however much an individual director applied their weight. Some artists flourished under such conditions despite the system (John Ford, Howard Hawks), while others still were squashed by it (Orson Welles, Preston Sturges), propelling the studio era’s unsympathetic reputation. However unsavory such practices could be, most films from this era are lumped into that ever ambiguous “genre” known as Classic.

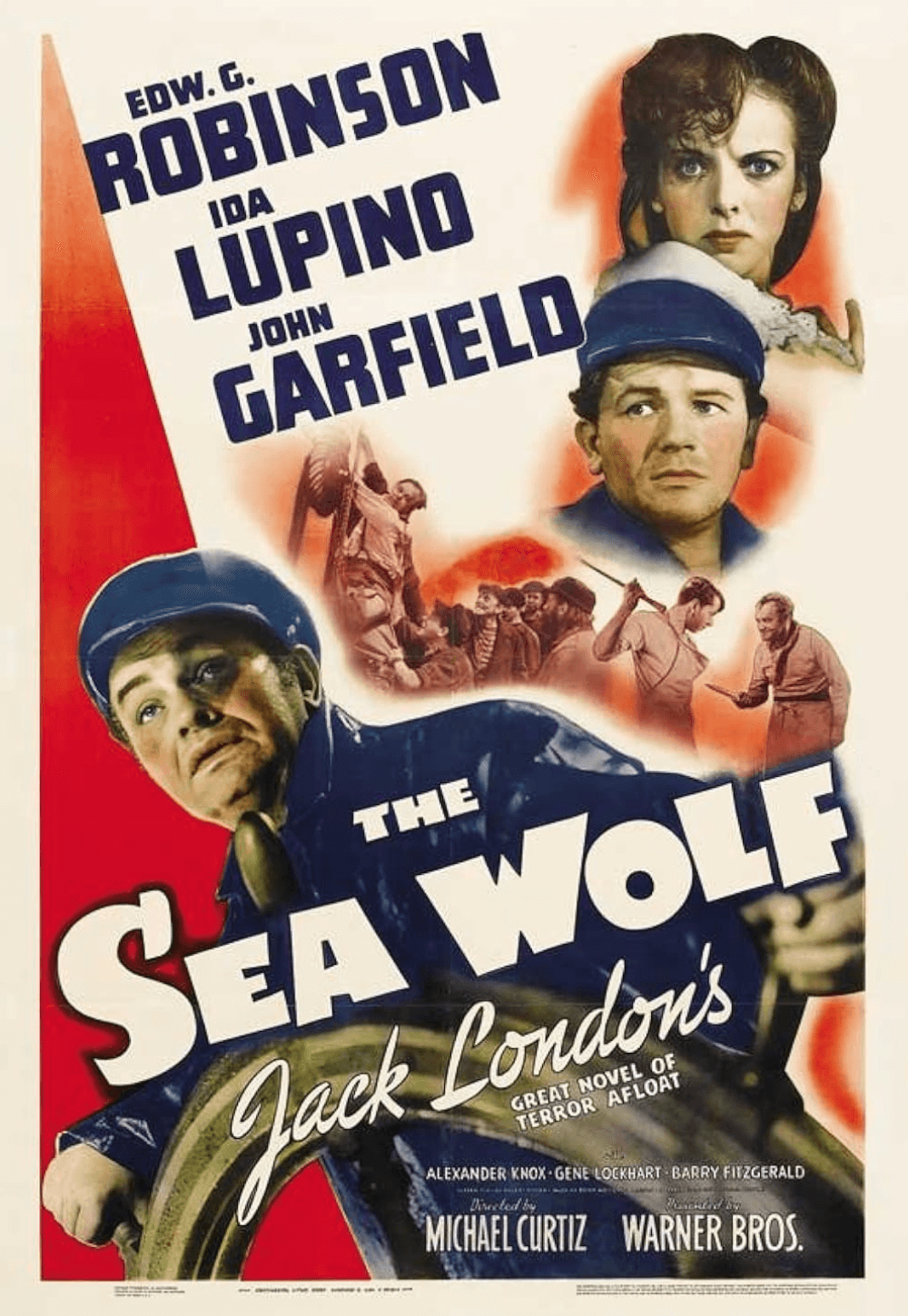

For Warner Bros., Casablanca was just another name on the production schedule for 1942. Story editor Irene Lee suggested Joan Alison and Murray Burnett’s then-unproduced play Everybody Comes to Rick’s to producer Hal B. Wallis, who would later take credit for the discovery. Days after the attack on Pearl Harbor in early December of 1941, Wallis was already shopping an outline around to top brass and seeking approvals, which were casually given. The treatment story contained enough anti-isolationism commentary to rouse any American from their complacency, to get them to choose their duty to the world as human beings over their love for the individual, which is exactly what the self-sacrificial ending of Casablanca advises. But this thematic relevance was merely the device through which a thrilling melodrama was told. Without recounting each and every plot detail from a film moviegoers have undoubtedly seen umpteen times, Casablanca contains intermingled themes of lost love, social narcissism, self-preservation, and patriotism. Each theme presents an ostensibly separate narrative strain incorporated by any one of the film’s several writers, both credited and uncredited. Brothers Julius and Philip Epstein, Howard Koch, Casey Robinson, and other untraceable Warner Bros. stock writers collaborated through their assortment of notes and dialogue and subplots. Jack Warner put forward nothing by way of creative input on Casablanca’s production aside from recommending that George Raft star as Rick. Wallis replied to Warner via inner-studio memorandum, insisting the role would be written for Humphrey Bogart’s sensibilities.

For Warner Bros., Casablanca was just another name on the production schedule for 1942. Story editor Irene Lee suggested Joan Alison and Murray Burnett’s then-unproduced play Everybody Comes to Rick’s to producer Hal B. Wallis, who would later take credit for the discovery. Days after the attack on Pearl Harbor in early December of 1941, Wallis was already shopping an outline around to top brass and seeking approvals, which were casually given. The treatment story contained enough anti-isolationism commentary to rouse any American from their complacency, to get them to choose their duty to the world as human beings over their love for the individual, which is exactly what the self-sacrificial ending of Casablanca advises. But this thematic relevance was merely the device through which a thrilling melodrama was told. Without recounting each and every plot detail from a film moviegoers have undoubtedly seen umpteen times, Casablanca contains intermingled themes of lost love, social narcissism, self-preservation, and patriotism. Each theme presents an ostensibly separate narrative strain incorporated by any one of the film’s several writers, both credited and uncredited. Brothers Julius and Philip Epstein, Howard Koch, Casey Robinson, and other untraceable Warner Bros. stock writers collaborated through their assortment of notes and dialogue and subplots. Jack Warner put forward nothing by way of creative input on Casablanca’s production aside from recommending that George Raft star as Rick. Wallis replied to Warner via inner-studio memorandum, insisting the role would be written for Humphrey Bogart’s sensibilities.

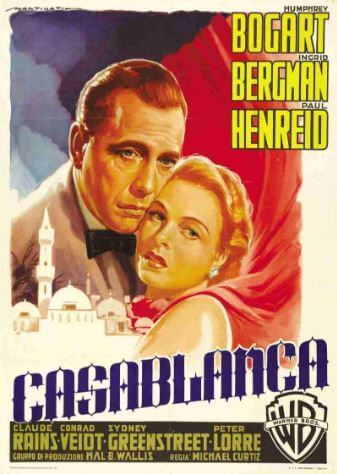

Bogart stars as Rick Blaine, an American expatriate whose upscale club Rick’s Café Américain is the Moroccan city of Casablanca’s top nightspot. Populated by black-marketeers, pickpockets, and an international gathering of witless travelers and unsavory types, Rick’s, and of course all of Vichy-occupied Casablanca bears a desperate and dangerous atmosphere. Except Rick’s clientele is not his concern; a bitter and wounded man, Rick confirms, “I stick my neck out for nobody.” His outlook is shared by most of Casablanca’s temporary citizens, including the local Vichy authority and incorrigible opportunist Captain Louis Renault (Claude Rains), who answers only to visiting Nazi Major Heinrich Strasser (Conrad Veidt). After a murder-theft in the first scene, two stolen signed letters of transit are obtained by fraught thief Ugarte (Peter Lorre); they provide safe passage through Nazi checkpoints all over Europe. Casablanca’s sordid streets and markets are the waiting ground for lost souls hoping to escape Hitler’s burgeoning reign, and whoever has the letters could gain transportation from Casablanca to Portugal and from there to freedom. Ugarte passes the letters to Rick for safe keeping, and when Ugarte is shot dead during his botched escape attempt from Renault’s men, the letters conveniently stay with Rick, and present the ultimate bargaining chip.

Enter Czech resistance fighter Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) and his wife Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman), who visit Rick on advice from the Blue Parrot Café owner Signor Ferrari (Sydney Greenstreet) to plead for the letters of transit. Meanwhile, Major Strasser has no intention of allowing Laszlo to escape Nazi capture once again, so whoever has the letters is under the hot lights of Nazi intimidation, Vichy establishment, and the suspicious eyes of Casablanca’s seedy and bribable underground. Shaking Rick from his isolationist framework is Isla, with whom he shared a lover’s tryst in Paris that ended abruptly when she left him for Laszlo. Heartbroken and sour since his abandonment, Rick refuses Laszlo and Isla the letters of transit no matter the price out of romantic spite. Her mere presence tortures him, punctuated by their song “As Time Goes By”, crooned by Rick’s faithful friend and piano player Sam (Dooley Wilson). When Isla confronts the forlorn Rick on her own, she explains that she believed her husband was dead in a concentration camp when she and Rick met in Paris, but when Laszlo resurfaced and was alive she had to return to him. Still, being in each other’s company rekindles their mutual ardor, and Rick agrees to help Laszlo if Isla stays behind. When they arrive at the airport, however, Rick sends husband and wife on their way, letting his love go in a gesture of self-sacrifice and nationalistic humanism.

Enter Czech resistance fighter Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) and his wife Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman), who visit Rick on advice from the Blue Parrot Café owner Signor Ferrari (Sydney Greenstreet) to plead for the letters of transit. Meanwhile, Major Strasser has no intention of allowing Laszlo to escape Nazi capture once again, so whoever has the letters is under the hot lights of Nazi intimidation, Vichy establishment, and the suspicious eyes of Casablanca’s seedy and bribable underground. Shaking Rick from his isolationist framework is Isla, with whom he shared a lover’s tryst in Paris that ended abruptly when she left him for Laszlo. Heartbroken and sour since his abandonment, Rick refuses Laszlo and Isla the letters of transit no matter the price out of romantic spite. Her mere presence tortures him, punctuated by their song “As Time Goes By”, crooned by Rick’s faithful friend and piano player Sam (Dooley Wilson). When Isla confronts the forlorn Rick on her own, she explains that she believed her husband was dead in a concentration camp when she and Rick met in Paris, but when Laszlo resurfaced and was alive she had to return to him. Still, being in each other’s company rekindles their mutual ardor, and Rick agrees to help Laszlo if Isla stays behind. When they arrive at the airport, however, Rick sends husband and wife on their way, letting his love go in a gesture of self-sacrifice and nationalistic humanism.

Film lovers can testify that any attempt at plot summary, even the skeletal outline above, barely hints at the film’s subtexts and innuendo, each sewn into the narrative by Wallis’ endless preoccupation with perfecting the script and tightening the many writerly strings, adding to the complex weave of conflicts that gloriously converge and resolve in the end. Short of analyzing each and every scene with equal parts academic and personal appreciation, no summary will ever capture the magic of what happens onscreen, as every character is driven by secret motives and saddening backstories. What one comes to realize when attempting to summarize the film’s events is that every moment is important to the narrative, every line of dialogue memorable, and every nuanced inflection by the cast skilled acting beyond compare. Praising this or that moment becomes an arbitrary selection process because the entire film plays like a familiar and iconic textbook that must be watched and enjoyed and loved to be appreciated.

Though Wallis supervised the muddled production, too much emphasis is placed on the details of the sordid production history, which inevitably and unfortunately becomes the centerpiece in discussions about Casablanca. These stories lend an interesting background, but hardly reveal anything essential about why the end result has earned its iconic status. What remains vital about how the film was made is the process by which the story was preemptively dissected, as if metonyms were selected before the decisive metaphor. Entendre-laden banter, visually dynamic setups, and flowing camera movements rushing to frame the uniquely handsome Bogart and stunning Bergman were perfected as an individual moment for cinema, with and without due consideration for the end product. Since writers were still compiling the story during the filming process, the cast and crew could only think of the scene being filmed as it was being filmed. As a result, each individual moment in Casablanca has as much polish as the remainder.

Though Wallis supervised the muddled production, too much emphasis is placed on the details of the sordid production history, which inevitably and unfortunately becomes the centerpiece in discussions about Casablanca. These stories lend an interesting background, but hardly reveal anything essential about why the end result has earned its iconic status. What remains vital about how the film was made is the process by which the story was preemptively dissected, as if metonyms were selected before the decisive metaphor. Entendre-laden banter, visually dynamic setups, and flowing camera movements rushing to frame the uniquely handsome Bogart and stunning Bergman were perfected as an individual moment for cinema, with and without due consideration for the end product. Since writers were still compiling the story during the filming process, the cast and crew could only think of the scene being filmed as it was being filmed. As a result, each individual moment in Casablanca has as much polish as the remainder.

Taken from production materials from the Warner vaults detailing brief communications between Wallis, director Michael Curtiz, and other production staff, most making-of histories for Casablanca are bemused critical notes on how none of it should have worked but all of it did. Wallis’ eye for detail becomes apparent in every memorandum. He insists upon an actual parrot outside of the Blue Parrot Café and sends Curtiz suggestions on how to incorporate subtext into various scenes. He famously wrote the film’s last piece of dialogue after filming had wrapped in August of 1942; well into the post-production process, Bogart returned to loop Wallis’ optimistic line, “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship…” Overseeing the production with the personal involvement he turned over on every project from The Charge of the Light Brigade to The Furies, Wallis kept the on-set pandemonium from overwhelming everyone involved and even flourished in this type of frantic creative environment.

Behind the camera, Curtiz’s ingenuity hides the film’s studio artifice; shooting on the Warner Bros. lot, save for a brief scene at Van Nuys airport, allowed complete control over the set pieces and seemingly diminutive production elements. Even the final airfield scene was shot in the studio, Curtiz using a wooden airplane veneer and “midgets” to give the runway and its crew the illusion of distance and scale; this Hollywood trickery was masked by the abundant fog in the scene, insisted upon by Curtiz to hide his visual deception. His use of shadows and high contrast lighting to activate his frame, for example, was long established in his Hollywood career before film noir was labeled a stylistic signature. Curtiz’s place behind the camera affords each otherwise obvious moment a sparkle that cleans away and avoids feeling artificial or plagiaristic, rather the opposite. While much of Casablanca contains moody tonal signs of film noir photography, many of the attributed characteristics were simply those derived from Curtiz’s necessity for personal style. Curtiz’s talent is not simply the product of the studio system, but an artistic force working within that system, and succeeding despite its downfalls. That audiences can watch Casablanca today, compare it to the director’s Mildred Pierce or Captain Blood in technical and even thematic terms, and clearly identify where Curtiz’s camera likes to go—how his shots zoom, how his pace never dawdles, and how through subtle emphatic additions he punctuates the drama in his screen stories—speaks volumes for Curtiz being more than a faceless employee of a Hollywood studio. Without this director at the helm, Casablanca would have resulted in another anonymous and generic release from the Warner Bros. production line.

Without Humphrey Bogart, however, the picture would fail to envelop us as it does. Then in his forties, Bogart was typecast as Hollywood’s tough guy in High Sierra and The Roaring Twenties. Rick Blaine, like Bogart, was an unlikely romantic figure, which is why Bogart’s transformation into Rick is so powerful. That hardened-misanthrope-turned-romantic-at-heart onscreen persona would follow Bogart for the rest of his career for roles in To Have and Have Not and The African Queen. After the film’s release and success, Bogart surpassed Errol Flynn as Warner’s top star, largely from the restructuring of his onscreen persona. Curious for a romantic lead, his long, worn features and unimpressive physique did not exude the characteristics of a sex symbol; in truth, Bogart was two inches shorter than Bergman, so he stood on books in their scenes together. And yet, his ease and magnetism as Rick draws the audience, as does the character’s perceptible mystery. In Rick’s Café Américain, nobody can stop talking about Rick, and when he finally appears he is just as intriguing as we might expect. The role and the actor converge into a genuine performance, seductive and serious, but hidden emotionally and fascinating for it.

Without Humphrey Bogart, however, the picture would fail to envelop us as it does. Then in his forties, Bogart was typecast as Hollywood’s tough guy in High Sierra and The Roaring Twenties. Rick Blaine, like Bogart, was an unlikely romantic figure, which is why Bogart’s transformation into Rick is so powerful. That hardened-misanthrope-turned-romantic-at-heart onscreen persona would follow Bogart for the rest of his career for roles in To Have and Have Not and The African Queen. After the film’s release and success, Bogart surpassed Errol Flynn as Warner’s top star, largely from the restructuring of his onscreen persona. Curious for a romantic lead, his long, worn features and unimpressive physique did not exude the characteristics of a sex symbol; in truth, Bogart was two inches shorter than Bergman, so he stood on books in their scenes together. And yet, his ease and magnetism as Rick draws the audience, as does the character’s perceptible mystery. In Rick’s Café Américain, nobody can stop talking about Rick, and when he finally appears he is just as intriguing as we might expect. The role and the actor converge into a genuine performance, seductive and serious, but hidden emotionally and fascinating for it.

Wallis borrowed Ingrid Bergman from David O. Selznick for $25,000, though she turned down Casablanca originally to costar in For Whom the Bell Tolls; in time, scheduling conflicts eased, allowing her to star in both. Bergman restrains her emotions in an unintentional yet affecting display of confused sensations, showing the actress’ inner uncertainty at where her character would end up, since no one knew the outcome of their film until shooting commenced on the final scene. Bergman’s portrayal of Ilsa relies on her tortured expressions that convey her wavering between her husband Victor, and Rick. Cinematographer Arthur Edeson, who also filmed The Maltese Falcon and Sergeant York, shot Bergman through soft filters that made her appearance dreamlike, her eyes glossing and ready for certain tears. Like Bogart, Casablanca made Bergman into the Hollywood icon she is today, and only her performance in Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious challenges her glowing beauty and heart-wrenching depiction here.

Overlooked next to the film’s two headlining stars, Claude Rains’ ever-present charm and elegant wit enliven Captain Renault, a character whose corruption knows no bounds. Renault accepts suggested sexual favors from young attractive women for travel visas, he gambles and then a moment later shuts down the establishment for illegal gaming (but not before collecting his winnings), and fully enjoys the extravagances of his station. “It is a little game we play,” he remarks about his tab, “They put it on the bill, I tear up the bill. It is very convenient.” His dialogue is Casablanca’s most flavored, lightened by Rains’ fine intonation bordering on flirtatious admiration toward Rick—discussing Ilsa, Renault comments, “She was asking about you earlier in a way that made me very jealous…” Rains was typically a supporting actor, providing wise fatherly figures and devilish villains opposite lively heroes usually played by Errol Flynn (see The Adventures of Robin Hood), though he appeared (or not) as the title role in The Invisible Man. Classically trained, his presence always provided a smooth and likable character, his wry smile adding to his allure. Indeed, opposite Bergman and Cary Grant in Notorious, he embodied cinema’s only sympathetic Nazi.

Overlooked next to the film’s two headlining stars, Claude Rains’ ever-present charm and elegant wit enliven Captain Renault, a character whose corruption knows no bounds. Renault accepts suggested sexual favors from young attractive women for travel visas, he gambles and then a moment later shuts down the establishment for illegal gaming (but not before collecting his winnings), and fully enjoys the extravagances of his station. “It is a little game we play,” he remarks about his tab, “They put it on the bill, I tear up the bill. It is very convenient.” His dialogue is Casablanca’s most flavored, lightened by Rains’ fine intonation bordering on flirtatious admiration toward Rick—discussing Ilsa, Renault comments, “She was asking about you earlier in a way that made me very jealous…” Rains was typically a supporting actor, providing wise fatherly figures and devilish villains opposite lively heroes usually played by Errol Flynn (see The Adventures of Robin Hood), though he appeared (or not) as the title role in The Invisible Man. Classically trained, his presence always provided a smooth and likable character, his wry smile adding to his allure. Indeed, opposite Bergman and Cary Grant in Notorious, he embodied cinema’s only sympathetic Nazi.

Warner Bros. rounded up the usual suspects from their expansive register of stock players to the Casablanca set for the remaining cast, but only Bogart and Dooley Wilson were Americans. The rest amassed from all over the world, most having fled Europe as Hitler came to power: Bergman was Swedish; Conrad Veidt was German; Paul Henreid and Peter Lorre were Austrian; Rains and Sydney Greenstreet were British; even director Michael Curtiz was Hungarian. Moreover, each player had their own matchless quality, from Lorre’s groveling snivel to Greenstreet’s slippery schemer-of-a-voice. Mirroring the horde of international orphans collected in one place as depicted in the film, the culturally diverse cast imparted authenticity to the colorful types on and offscreen. Upon the film’s initial release in New York City on November 26, 1942, Allied forces invaded North Africa and eventually Casablanca, which Warner Bros. marketed as a modern parallel to raise awareness for the film. The wide release came more than a month later to coincide with Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and General Charles de Gaulle’s meeting at the Casablanca Conference. Earning a respectable profit at the box office and warm praises for being “splendid anti-Axis propaganda,” the film also won three Academy Awards, including Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Director, and Best Picture. Jack Warner accepted the Best Picture Oscar, even though traditionally the producer in charge of the production, in this case, the passionate, dedicated, and meticulous Hal B. Wallis, collects the statue. Wallis later voiced his resentment over Warner’s move. And aside from the rare detractor such as noted critic Pauline Kael, the universal acclaim has grown over the years, placing the film near the top of most best lists after Citizen Kane, though certainly audiences the world over are more impassioned and emotionally devoted to Casablanca over Orson Welles’ picture.

How appropriate then that “As Time Goes By” endures as Casablanca’s theme. Composer Max Steiner wrote nearly his entire score to compliment “La Marseillaise,” yet the musical accompaniment audiences remember is Herman Hupfeld’s gentle song from 1931. What other impressions from the film could exhibit the same reflective, memorializing effect over its audience, just as this song does for Rick and Ilsa? When Sam sits at his piano or Ilsa hums it to herself, the song wisps the characters away from the past where love was easy and time seemed to float. The song elicits the same reaction for viewers because as it plays, we remember the joyful experience of the whole film and escape into the pleasant simplicity of The Golden Age of moviemaking—as much a product of an unsound but strangely proficient and industrialized studio system the film may be. As time goes by, the song and Casablanca itself stay with us and mature through nostalgia and their enduring hypnotic spell.

How appropriate then that “As Time Goes By” endures as Casablanca’s theme. Composer Max Steiner wrote nearly his entire score to compliment “La Marseillaise,” yet the musical accompaniment audiences remember is Herman Hupfeld’s gentle song from 1931. What other impressions from the film could exhibit the same reflective, memorializing effect over its audience, just as this song does for Rick and Ilsa? When Sam sits at his piano or Ilsa hums it to herself, the song wisps the characters away from the past where love was easy and time seemed to float. The song elicits the same reaction for viewers because as it plays, we remember the joyful experience of the whole film and escape into the pleasant simplicity of The Golden Age of moviemaking—as much a product of an unsound but strangely proficient and industrialized studio system the film may be. As time goes by, the song and Casablanca itself stay with us and mature through nostalgia and their enduring hypnotic spell.

The film demands our attention over and over again, and multiple viewings and the observations therein inspire familiar scenes to blossom from narrative meaning and historical subtext. And only because Casablanca was constructed piece by piece, attention never on the whole but rather a specific concentration on this moment, does the film seem imbued with layer after endless layer of individual meaning. Though virtually every scene and line of dialogue has been quoted, repeated, reused, and referenced, still the film captures us upon revisitation. We forget how individual lines or whole scenes are now clichés out of context, and we lose ourselves in the glory of the experience, allowing the effortlessness of this endearing romance to consume us. Scholarship, historical and interpretive analyses, and appreciations beyond count have been written about Casablanca, making any new words on the film inevitably redundant. And yet, still, there are new articles composed every year attesting to the film’s greatness, while at the same time hoping to capture exactly what about the film makes it such an iconic, venerable piece of filmmaking. But the fact that the discussion continues, despite the wealth of material already covered by historians and critics and film aficionados, remains the film’s most probing accomplishment. It continues to fascinate audiences in a way that is beyond explanation, except to resolve that the picture seems to result from and fully encompass that somewhat fantastical notion of Movie Magic.

Bibliography:

Harmetz, Aljean. Round Up the Usual Suspects: The Making of Casablanca. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1992.

Robertson, James C.. The Casablanca Man: The Cinema of Michael Curtiz. London; New York: Routledge, 1993.

Rosenzweig, Sidney. Casablanca and Other Major Films of Michael Curtiz. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1982.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. New York: Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. Bogie: a celebration of the life and films of Humphrey Bogart. London: Aurum, 2006.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review