The Definitives

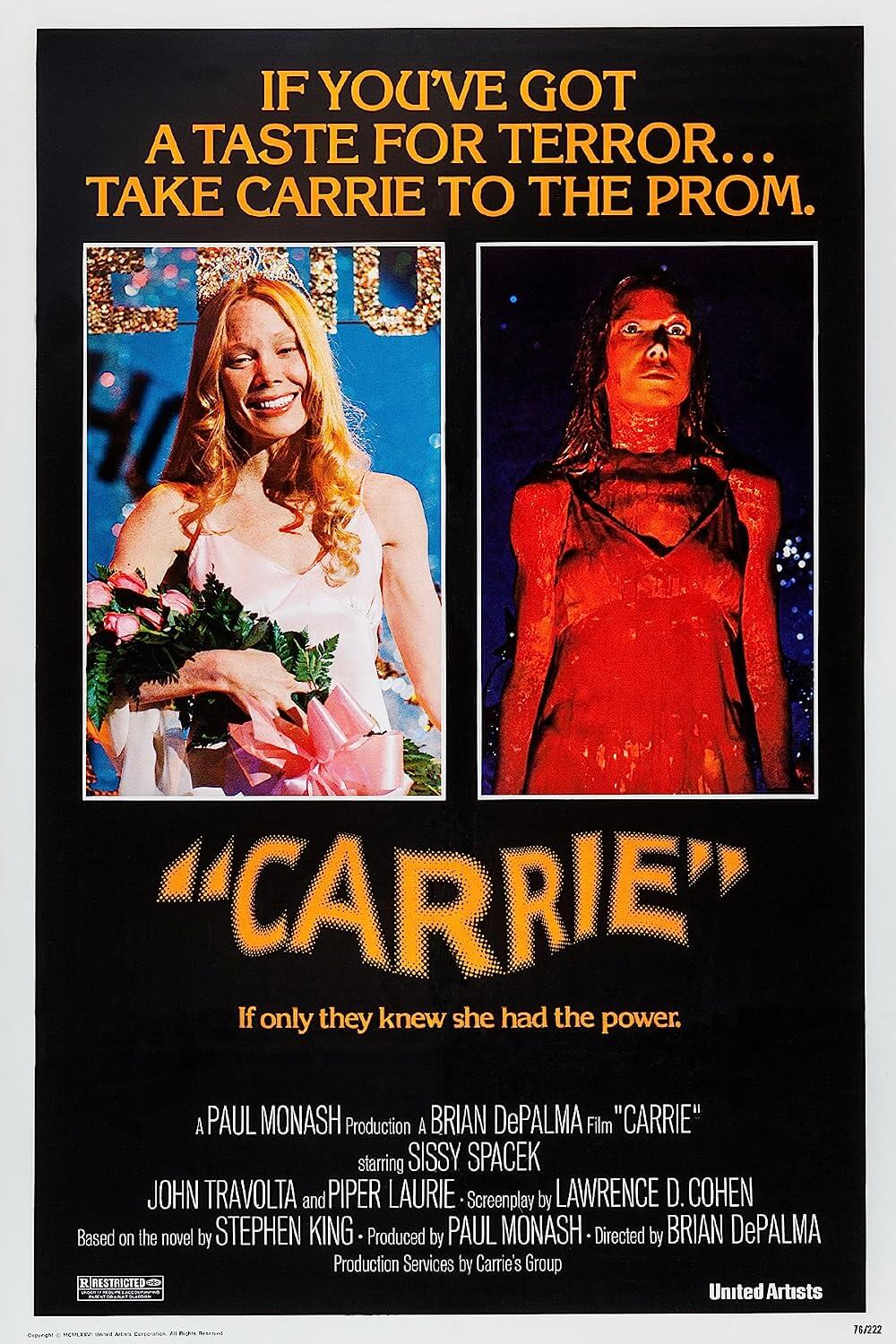

Carrie (1976)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Carrie opens with a scene whose trauma forces us to remember the fragile stage of youth, namely high school, and in turn, leads naturally, inescapably, and unrelentingly to the film’s shocking climax. In a fantasy locker room, the camera pans along a group of girls after gym, as they shower and dress, playfully slapping each other with white towels, the images of naked young bodies soft-filtered and rendered in slow-motion, like a pornographic dream designed to titillate us into voyeuristic spectatorship. Still showering, the withdrawn Carrie White caresses her body with soap as the water gently pours over her, her body filling the frame that sexualizes her until, all at once, director Brian De Palma reverses the scene from an erotic moment into a terrifying one. Blood begins to flow between Carrie’s legs; she looks on, concerned and confused at the red captured in her fingers. Carrie’s first period has arrived, but she hasn’t been told about menstruation or much of anything about puberty, so she runs to her fellow classmates in a panic, crying, “Help me!” They receive this late-bloomer with laughter and derision, quickly forming a pitiless mob to push her down into a corner, chanting “Plug it up!” as they toss tampons and pads at her. But then it’s doubtful Carrie knows how these items are used. Though gym teacher Miss Collins breaks up the scene, Carrie’s screams shatter a locker room light bulb in a burst of telekinesis, another gift of womanhood, this one exclusive to Carrie. Curled up on the floor, her body bleeding and mind reeling in terror, this is Carrie’s first moment as a woman, a moment which creates a lingering sense of dread that crescendos until the final, horrifying scenes of the picture.

Based on Stephen King’s first published novel from 1974, De Palma’s film of Carrie would catapult the visualist director into the mainstream consciousness through a motion picture of supreme staging and figurative melodrama. In Hollywood’s first major Stephen King adaptation of many, the writer’s oft-employed youth bullies so deplorably incite an outburst of violence and retribution that, when the eponymous character exacts widespread vengeance on her classmates, it feels almost fully justified in an extreme catharsis the likes of which only cinema could provide. Fortunately, De Palma avoids reducing King’s angry, heavy text into an exercise in shallow horror filmmaking where innocents are made victims by a central, demonized monster. Rather, the director’s approach considers with great care the emotional state of his maligned teenage protagonist. Carrie is a horror story in which the most ghastly turns come not from The Unknown or some fantastical abomination, but from the worst suspicions and contempt for women, realized through religion, social cruelty, and supernatural elements that have a direct connection to the film’s metaphor for the misunderstood and feared feminine prowess. De Palma enhances this quality further by creating an association between his characters and his own inspired technical flourishes; his high sense of cinematic style leaves every thrilling sequence drenched in visual metaphor, the material enriched by his masterful direction.

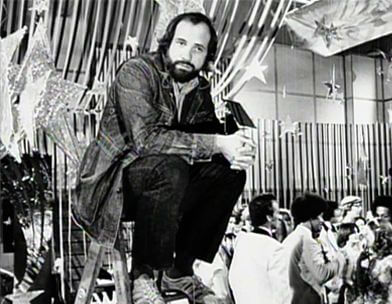

After several minuscule independent productions, Brian De Palma made his critical breakthrough with Sisters (1973), his first homage to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, followed by his rock opera Phantom of the Paradise (1974), and then his first Vertigo tribute of many, Obsession (1976). Each low-budget production gained De Palma esteem among his fellow cinema-savvy New Hollywood compatriots such as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, John Carpenter, Paul Schrader, and Steven Spielberg. But it wasn’t until a friend recommended that De Palma read and adapt King’s first published book that the director would find his path to box-office glory, as Mean Streets (1972) did for Scorsese or The Godfather (1972) did for Coppola. Lawrence D. Cohen adapted King’s epistolary text into a traditional narrative form, and United Artists gave De Palma nearly $2 million in budgetary dollars to work with, more than he had ever been granted before. In the title role, he cast Sissy Spacek, who was 27 when the film was shot and still a relatively new actress. Spacek had just appeared in Prime Cut (1972) and earned accolades for her performance in Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1973). Piper Laurie, who hadn’t been onscreen since 1961 in her Oscar-nominated performance in The Hustler, would play Carrie’s religion-crazed mother Margaret. Then a star of TV’s Welcome Back, Kotter, a young John Travolta, just a year before his star-making role in Saturday Night Fever, appeared alongside De Palma’s future wife Nancy Allen as Carrie’s worst tormentors (Allen and Travolta would star across each other again in De Palma’s Blow Out).

After several minuscule independent productions, Brian De Palma made his critical breakthrough with Sisters (1973), his first homage to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, followed by his rock opera Phantom of the Paradise (1974), and then his first Vertigo tribute of many, Obsession (1976). Each low-budget production gained De Palma esteem among his fellow cinema-savvy New Hollywood compatriots such as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, John Carpenter, Paul Schrader, and Steven Spielberg. But it wasn’t until a friend recommended that De Palma read and adapt King’s first published book that the director would find his path to box-office glory, as Mean Streets (1972) did for Scorsese or The Godfather (1972) did for Coppola. Lawrence D. Cohen adapted King’s epistolary text into a traditional narrative form, and United Artists gave De Palma nearly $2 million in budgetary dollars to work with, more than he had ever been granted before. In the title role, he cast Sissy Spacek, who was 27 when the film was shot and still a relatively new actress. Spacek had just appeared in Prime Cut (1972) and earned accolades for her performance in Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1973). Piper Laurie, who hadn’t been onscreen since 1961 in her Oscar-nominated performance in The Hustler, would play Carrie’s religion-crazed mother Margaret. Then a star of TV’s Welcome Back, Kotter, a young John Travolta, just a year before his star-making role in Saturday Night Fever, appeared alongside De Palma’s future wife Nancy Allen as Carrie’s worst tormentors (Allen and Travolta would star across each other again in De Palma’s Blow Out).

On a fifty-day shooting schedule, De Palma and his crew—including production designer Jack Fisk (Spacek’s husband) and cinematographer Mario Tosi (who replaced Isidore Mankofsky after an on-set row)—wrapped the production without major incident. Despite an intended meteorite sequence where Carrie’s house is destroyed by falling stones, which couldn’t be filmed due to technical problems, De Palma completed production and, along with his recurrent editor Paul Hirsch, set out to assemble the film while composer Pino Donaggio, whose work on Don’t Look Now (1973) had attracted De Palma, put the finishing touches on his Psycho-inspired score. After its release on November 3, 1976, Carrie went on to earn $33.8 million at the U.S. box office, making it one of the year’s most successful films. Although generally well received, Carrie was dismissed outright by many critics who failed to evaluate it in any meaningful way. Among the exceptions, Roger Ebert and Pauline Kael praised the film and its director and seemed to appreciate the full measure of De Palma’s film. Ebert called it “an absolutely spellbinding horror movie” and remarked, “We didn’t know De Palma, ordinarily so flashy on the surface, could go so deep.” Two years later, Carrie’s financial success led to another De Palma film about telekinetic youngsters, this one a profitable but lesser sensation. The Fury concerned Kirk Douglas as a former government agent determined to track down those who kidnapped his telekinetic son to harness his powers into a living weapon. An entertaining trifle with a curiously bloody finish, The Fury failed to connect with audiences the way its predecessor had, in part because the emotional stakes were not as clearly defined as De Palma had made them in Carrie.

Unlike the basis for King’s other single-name titles, such as Christine or Cujo, the subject of Carrie is not an inhuman monster. Carrie White is a protagonist worthy of our sympathy, whose supernatural abilities give her a unique opportunity to be seen as a monster, and later to resort to horrible acts of violence. At home, Carrie has been victimized by her fervently religious mother, a woman driven by her fear of sexuality. That fear has not been passed down to her daughter; however, it has left Carrie a timid and fearful specimen. Quoting her cultish reading material, Margaret speaks of the female curse of blood, a notion which, tragically, proves to be correct when she says, “First comes the blood, then comes the sin.” Blood preempts Carrie’s bursts of telekinesis, both in the girl’s locker room after her period and later during the film’s famous bloody prom finale. For Margaret, blood is the signifier for womanhood, which for her equates to sin. When Carrie’s mother finds out she’s “a woman now,” Margaret preaches her own sermon: “And God made Eve from the rib of Adam. And Eve was weak and loosed the raven on the world. And the raven was called sin… The first sin was intercourse… And Eve was weak… And the Lord visited Eve with the curse, and the curse was the curse of blood!” Donning a full black garb and speaking in a high-toned preacher-speak, Margaret locks her daughter in a closet as punishment for becoming a woman; inside, Carrie must light candles and pray to a crooked Saint Sebastian statue. Margaret, too, fears the power of women, having been wife to a rugged drunkard, the two of them conceiving their daughter in a viscerally described scene of lust so contrary to her piety. When Carrie reaches womanhood, Margaret has difficulty controlling her increasingly independent daughter, and Carrie’s telekinetic powers indicate to Margaret that she was right—embracing womanhood incites a pact with Satan and awards the powers of evil.

Unlike the basis for King’s other single-name titles, such as Christine or Cujo, the subject of Carrie is not an inhuman monster. Carrie White is a protagonist worthy of our sympathy, whose supernatural abilities give her a unique opportunity to be seen as a monster, and later to resort to horrible acts of violence. At home, Carrie has been victimized by her fervently religious mother, a woman driven by her fear of sexuality. That fear has not been passed down to her daughter; however, it has left Carrie a timid and fearful specimen. Quoting her cultish reading material, Margaret speaks of the female curse of blood, a notion which, tragically, proves to be correct when she says, “First comes the blood, then comes the sin.” Blood preempts Carrie’s bursts of telekinesis, both in the girl’s locker room after her period and later during the film’s famous bloody prom finale. For Margaret, blood is the signifier for womanhood, which for her equates to sin. When Carrie’s mother finds out she’s “a woman now,” Margaret preaches her own sermon: “And God made Eve from the rib of Adam. And Eve was weak and loosed the raven on the world. And the raven was called sin… The first sin was intercourse… And Eve was weak… And the Lord visited Eve with the curse, and the curse was the curse of blood!” Donning a full black garb and speaking in a high-toned preacher-speak, Margaret locks her daughter in a closet as punishment for becoming a woman; inside, Carrie must light candles and pray to a crooked Saint Sebastian statue. Margaret, too, fears the power of women, having been wife to a rugged drunkard, the two of them conceiving their daughter in a viscerally described scene of lust so contrary to her piety. When Carrie reaches womanhood, Margaret has difficulty controlling her increasingly independent daughter, and Carrie’s telekinetic powers indicate to Margaret that she was right—embracing womanhood incites a pact with Satan and awards the powers of evil.

Of the film, Pauline Kael wrote, “No one else has ever caught the thrill that teenagers get from a dirty joke and sustained it for a whole picture.” Carrie’s foremost tormentor Chris Hargensen (Allen) has such a cruel streak that throughout the picture the audience remains terrified at how Carrie will be afflicted. And when Chris’ plan finally comes to fruition, it’s worse than we could have imagined. At school, the gym teacher Miss Collins (Betty Buckley) punishes Carrie’s merciless classmates with a kind of correctional boot camp detention. When Chris rebels, Collins strikes her and bans her from prom; Chris vows revenge, and her unhinged rage over her sentence sends her frantic and scheming to her dim boyfriend, Billy Nolan (Travolta). There’s a growing sense of terror as, without an immediate explanation as to why, Chris convinces Billy to slaughter a pig at a farm in an almost ritualistic practice. What kind of humiliation has Chris conceived that requires a slaughtered pig? Later we see Chris and Billy place a bucket of pig’s blood in the gym rafters above the prom stage, and we see her “call in favors” with fellow classmates who oversee the prom royalty ballot box. Meanwhile, overwhelmed with shame for her behavior toward Carrie, Sue Snell (Amy Irving) resolves to atone for her misdeeds by setting up Carrie with her own boyfriend, Tommy Ross (William Katt), as a date to prom. Miss Collins warns both Sue and Tommy that it had better not be a practical joke, but their intentions seem genuine enough—they want to give Carrie the sort of dreamy prom she might not have otherwise.

Early in Carrie, there’s a clever poetry lesson scene where Tommy reads a plagiarized poem and, a few seats back, Carrie listens on, oblivious and enamored. De Palma frames the scene with a split-diopter lens, Tommy’s embarrassed expressions in the foreground and Carrie’s sincerity in the background, the teacher Mr. Fromm (Sydney Lassick) remarking on what Carrie calls Tommy’s “beautiful” poem. Then, on the pretense that he’s asking her to prom because she liked his poem, Tommy begrudgingly agrees to Sue’s behest to ask Carrie, and, albeit hesitantly, the introverted girl agrees. For Carrie, Tommy represents the ultimate hope of fitting in—an otherwise impossible chance to “be normal” coming true. Of course, Carrie must battle with her mother’s protests (“They’re all going to laugh at you!”) until Carrie shocks Margaret into submission with her abilities and resolves to attend, permitted or not. She even makes her own prom dress (“Red. I might have known it would be red,” Margaret remarks, though Carrie’s dress is pale pink). At the prom, Tommy talks with Carrie, and we begin to see his resentment over the situation melt away; he tries to convince her to come out of her shell, and perhaps even develops an affection for this shy, pretty girl. But Carrie cannot see the full picture of Sue and Tommy’s well-meaning rouse, nor Chris and Billy’s forces working against her. All the while, the audience still feels a sense of dread about whatever nasty plot Chris has concocted. The feeling of being swept up in the moment reaches its zenith when Carrie and Tommy dance in a wistful, spinning sequence. De Palma begins the soft-filtered scene like that in the locker room opening—dreamy and even melodramatic in its fantasy pleasures. The camera orbits around the blissful couple but gradually gains speed and seems to spiral out of control, just as Carrie has lost herself in happiness and hope for normalcy.

Early in Carrie, there’s a clever poetry lesson scene where Tommy reads a plagiarized poem and, a few seats back, Carrie listens on, oblivious and enamored. De Palma frames the scene with a split-diopter lens, Tommy’s embarrassed expressions in the foreground and Carrie’s sincerity in the background, the teacher Mr. Fromm (Sydney Lassick) remarking on what Carrie calls Tommy’s “beautiful” poem. Then, on the pretense that he’s asking her to prom because she liked his poem, Tommy begrudgingly agrees to Sue’s behest to ask Carrie, and, albeit hesitantly, the introverted girl agrees. For Carrie, Tommy represents the ultimate hope of fitting in—an otherwise impossible chance to “be normal” coming true. Of course, Carrie must battle with her mother’s protests (“They’re all going to laugh at you!”) until Carrie shocks Margaret into submission with her abilities and resolves to attend, permitted or not. She even makes her own prom dress (“Red. I might have known it would be red,” Margaret remarks, though Carrie’s dress is pale pink). At the prom, Tommy talks with Carrie, and we begin to see his resentment over the situation melt away; he tries to convince her to come out of her shell, and perhaps even develops an affection for this shy, pretty girl. But Carrie cannot see the full picture of Sue and Tommy’s well-meaning rouse, nor Chris and Billy’s forces working against her. All the while, the audience still feels a sense of dread about whatever nasty plot Chris has concocted. The feeling of being swept up in the moment reaches its zenith when Carrie and Tommy dance in a wistful, spinning sequence. De Palma begins the soft-filtered scene like that in the locker room opening—dreamy and even melodramatic in its fantasy pleasures. The camera orbits around the blissful couple but gradually gains speed and seems to spiral out of control, just as Carrie has lost herself in happiness and hope for normalcy.

Having made their way into the prom and under the stage, Chris and Billy have arranged for Tommy and Carrie to be crowned prom king and queen, and in a flurry of giddy hatefulness, Chris clutches the rope that will pull down the bucket of pig’s blood onto Carrie. In true Hitchcockian fashion, De Palma uses our awareness of the bucket to drive us mad with equal parts anticipation and suspense toward the climax. Our anxiety is unbearable now, De Palma brilliantly extending the film-long tension we’ve felt by rendering Tommy and Carrie’s crowning in a deliberately paced slow-motion tracking shot. The director pans over a cheering audience, proud teachers, and the winning couple, all so unreservedly optimistic at the perfection of the scene that the image must be from Carrie’s lost-in-the-moment perspective. De Palma then cross-cuts to Sue, who has made her way backstage to watch and feel redeemed by her orchestration of Carrie’s happiness, but now notices the rope and the bucket. And then, just as Miss Collins ejects Sue from the prom in a misguided fear that Sue might ruin Carrie’s moment, it happens. Still in slow motion, Chris pulls the rope, and the bucket drenches Carrie in a horrific shower of red. The audience goes silent. Tommy shouts his objection until the bucket falls onto his head and he collapses, unconscious and perhaps dead. A student breaks the silence with laughter, though Donaggio’s score drowns out all else. Then, from Carrie’s perspective, everyone begins to laugh in a kaleidoscopic nightmare. And now, it seems, Carrie’s mother was right. Even if it was inspired by religious extremism, at least Margaret was correct in her prediction that the evening would be a catastrophe.

De Palma interrupts his slow-motion with Carrie’s sharp reaction, indicated by Spacek’s sudden lizard-like expressions and neck movements through which her character directs telekinetic vengeance. A split-screen effect displays both Carrie’s warped gestures and the bloody outcome of her abilities as she locks her entire school inside the gym and sets it ablaze, killing everyone in an eruption of unrestrained, utterly traumatized emotional energy. Not even Miss Collins, Carrie’s ardent protector, survives. Carrie’s emotional fragility has warped everyone into enemies now. Chris and Billy have escaped out the back and, as Carrie walks home drenched in blood, she detonates their car before they can run her down. And though everyone at school is gone, Carrie’s nightmare has not ended. She arrives home and bathes herself clean, then embraces her mother, who was right after all. Margaret, convinced her daughter is evil, responds by stabbing Carrie, who in turn uses her ability to send knives soaring into her mother. Perhaps unconsciously, Carrie has propelled the knives in such a way that her mother is left in the same stance as the Saint Sebastian statue in the White house’s punishment closet. Carrie has nothing now, and the power that she believed was a miracle from God has seemingly damned her. Without warning, the house begins to tremble and collapse in on itself with Carrie inside. Who can say whether it’s some godly force punishing her or simply Carrie’s unconscious desire to end it all that burns the White house to the ground? In the aftermath, only Sue has survived. The last of De Palma’s reversals is one of the film’s best. Again soft-filtered, the scene shows Sue approaching the remains of the White house where she sets down flowers. As she does, Carrie’s bloody arm reaches out from the rubble and shocks Sue awake. Sue stirs from her nightmare, screaming in her mother’s arms, fated never to forget what she helped start.

De Palma interrupts his slow-motion with Carrie’s sharp reaction, indicated by Spacek’s sudden lizard-like expressions and neck movements through which her character directs telekinetic vengeance. A split-screen effect displays both Carrie’s warped gestures and the bloody outcome of her abilities as she locks her entire school inside the gym and sets it ablaze, killing everyone in an eruption of unrestrained, utterly traumatized emotional energy. Not even Miss Collins, Carrie’s ardent protector, survives. Carrie’s emotional fragility has warped everyone into enemies now. Chris and Billy have escaped out the back and, as Carrie walks home drenched in blood, she detonates their car before they can run her down. And though everyone at school is gone, Carrie’s nightmare has not ended. She arrives home and bathes herself clean, then embraces her mother, who was right after all. Margaret, convinced her daughter is evil, responds by stabbing Carrie, who in turn uses her ability to send knives soaring into her mother. Perhaps unconsciously, Carrie has propelled the knives in such a way that her mother is left in the same stance as the Saint Sebastian statue in the White house’s punishment closet. Carrie has nothing now, and the power that she believed was a miracle from God has seemingly damned her. Without warning, the house begins to tremble and collapse in on itself with Carrie inside. Who can say whether it’s some godly force punishing her or simply Carrie’s unconscious desire to end it all that burns the White house to the ground? In the aftermath, only Sue has survived. The last of De Palma’s reversals is one of the film’s best. Again soft-filtered, the scene shows Sue approaching the remains of the White house where she sets down flowers. As she does, Carrie’s bloody arm reaches out from the rubble and shocks Sue awake. Sue stirs from her nightmare, screaming in her mother’s arms, fated never to forget what she helped start.

After Carrie’s release, a number of offshoots sprung from its box-office triumph, each employing a story in which revenge-bent teenagers exact violent retribution on others through supernatural means: Piper Laurie stars as the titular role in Ruby (1977), about a woman whose mute daughter takes psychic revenge on the mobsters that killed her father; Jennifer (1978) followed a girl whose prep-school tormentors receive their just deserts by way of the eponymous character’s ability to control snakes. However, Carrie’s most significant influence was on Hollywood as a whole; the film had demonstrated the box-office wellspring that could result from Stephen King’s source material. In the decades to come, King would become the most adapted modern author of his time, spawning both emotional horror and dramatic prestige pictures. Tobe Hooper’s made-for-TV movie Salem’s Lot (1978), Stanley Kubrick’s horror epic The Shining (1980), David Cronenberg’s intense drama The Dead Zone (1981), John Carpenter’s underrated Christine (1983), Rob Reiner’s Misery (1990), and Frank Darabont’s The Mist (2007) would all explore the darker side of King with the same skill as De Palma. Darabont’s adaptations The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and The Green Mile (1999), Taylor Hackford’s Dolores Claiborne (1995), and Bryan Singer’s Apt Pupil (1998) would show the author’s capacity for material beyond pure horror.

The 1970s elevated the horror genre from lowbrow entertainment to artistic heights with titles like The Exorcist (1973) and Jaws (1975), and just like those pictures, labeling Carrie as just “a horror film” does it an injustice. The implications of such a narrow definition overlook the depth of character that De Palma and Cohen instill to make Carrie more than just an abstract monster. In King’s 1981 nonfiction book Danse Macabre, a study of horror fiction’s influence on American culture, the author wrote that Carrie is about “what men fear about women and women’s sexuality.” Carrie’s mother fears what her religion tells her is a connection between womanhood and sin, her classmates despise that she allowed her womanliness to show itself so externally in the locker room, and the audience fears the way her femininity materializes into jolts of telekinesis. These fears are representative of a history of misunderstanding and generalized fears toward women. And yet, Carrie was written by a male who recognizes his own fear of women and uses that against his main character and his reader. Moreover, the film was made by a director who was later accused of chauvinism and exploiting female sexuality in his films. And while an argument could be made against Carrie for its voyeuristic tendencies, De Palma and Cohen have intentionally muted Carrie’s prevalent psychic abilities, overly emphasized in King’s book, to create a direct correlation between her emotional state and supernatural outbursts, transforming the character into a distinctly human protagonist whose fragile psyche gives way to her telekinetic retaliation. Where King’s book featured a mysterious, seemingly unholy version of Carrie White who could create meteor showers and scan people’s minds telepathically, the film considers Carrie and her abilities defined by her delicate state, tremendous emotions, and abhorrent persecution as a woman.

The 1970s elevated the horror genre from lowbrow entertainment to artistic heights with titles like The Exorcist (1973) and Jaws (1975), and just like those pictures, labeling Carrie as just “a horror film” does it an injustice. The implications of such a narrow definition overlook the depth of character that De Palma and Cohen instill to make Carrie more than just an abstract monster. In King’s 1981 nonfiction book Danse Macabre, a study of horror fiction’s influence on American culture, the author wrote that Carrie is about “what men fear about women and women’s sexuality.” Carrie’s mother fears what her religion tells her is a connection between womanhood and sin, her classmates despise that she allowed her womanliness to show itself so externally in the locker room, and the audience fears the way her femininity materializes into jolts of telekinesis. These fears are representative of a history of misunderstanding and generalized fears toward women. And yet, Carrie was written by a male who recognizes his own fear of women and uses that against his main character and his reader. Moreover, the film was made by a director who was later accused of chauvinism and exploiting female sexuality in his films. And while an argument could be made against Carrie for its voyeuristic tendencies, De Palma and Cohen have intentionally muted Carrie’s prevalent psychic abilities, overly emphasized in King’s book, to create a direct correlation between her emotional state and supernatural outbursts, transforming the character into a distinctly human protagonist whose fragile psyche gives way to her telekinetic retaliation. Where King’s book featured a mysterious, seemingly unholy version of Carrie White who could create meteor showers and scan people’s minds telepathically, the film considers Carrie and her abilities defined by her delicate state, tremendous emotions, and abhorrent persecution as a woman.

Carrie is a punishing experience, ever ready to deliver some inconceivable blow against the audience just after the director has deceived us into thinking both Carrie and the audience were safe. De Palma manipulates his viewers in a series of reversals where a hopeful fantasy leads to a horrific outcome, and he expertly stages sequences with a technical daring that accumulates suspense until the shocking humiliation at prom. De Palma’s unexpected consideration of Carrie, fuelled by the film’s melodramatic touches and accentuated by Donaggio’s score, resists the interpretation that Carrie is the film’s resident monster. Indeed, her telekinetic abilities are almost forgotten as we’re consumed by her subjectivity and the suspense of everything going on around Carrie, such as her classmates’ plans to build up and, conversely, humiliate her at prom. The film acknowledges both a conscious and unconscious fear of women by embracing this sad tradition in the story’s horrific turns and condemning it through the dramatic substance and compassion felt for the main character. As such, Carrie White represents the long and often lost battle fought by women persecuted for their femininity, wherein even their victories are damned, in such a way that the fear itself of women becomes Carrie’s central monster.

Bibliography:

Aisenberg, Joseph. Studies in the Horror Film: Brian De Palma’s Carrie. Lakewood, CO: Centipede Press, 2011.

Keesey, Douglas. Brian De Palma’s Split-Screen. Mississippi: The University Press of Mississippi, 2015.

Peretz, Eyal. Becoming Visionary: Brian De Palma’s Cinematic Education of the Senses. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review