The Definitives

Captain Blood (1935)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

(Note: This essay was originally published on April 7, 2009. It has been edited and expanded.)

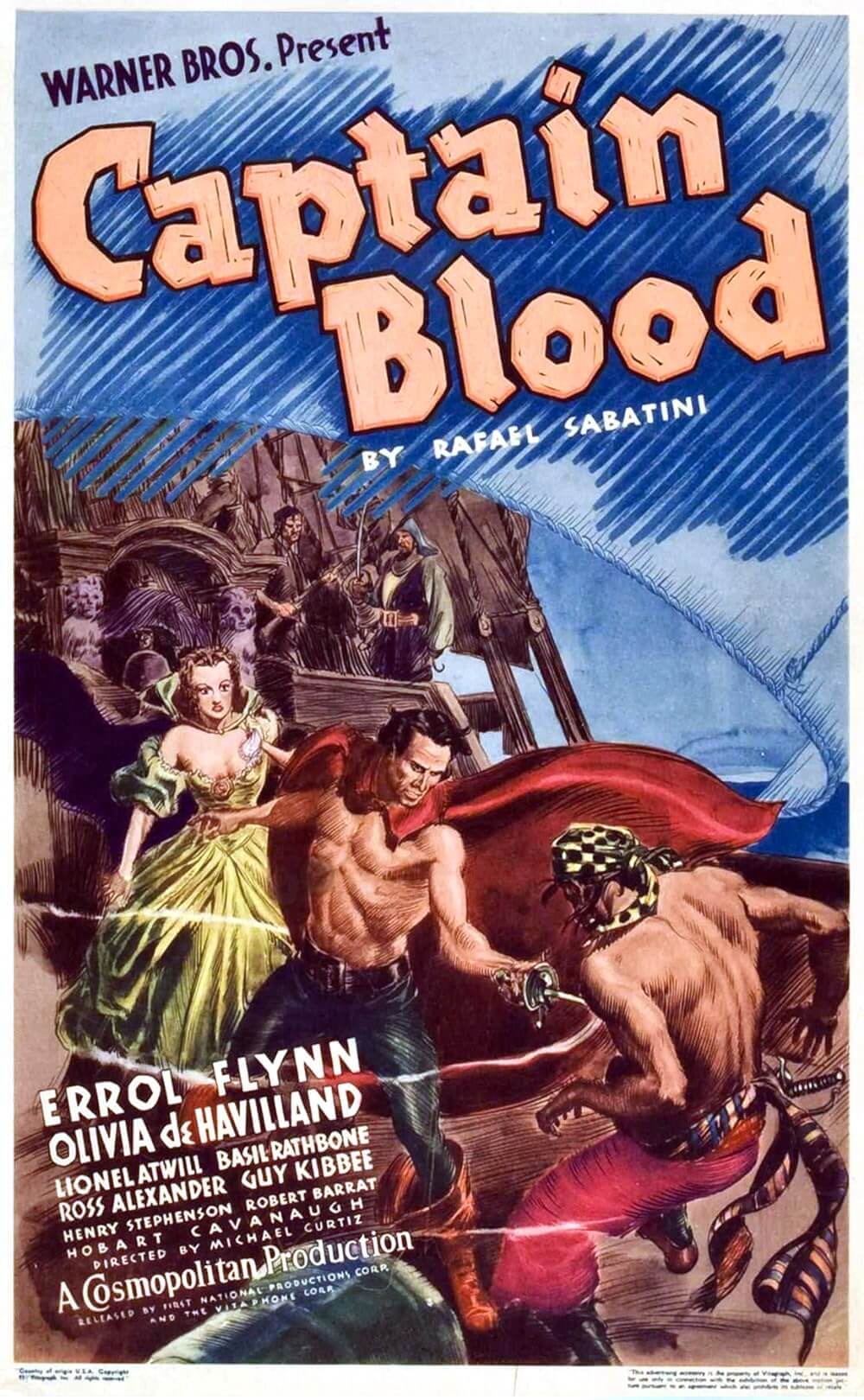

Captain Blood is a bold, swashbuckling adventure. Released in 1937, the film marshals the kind of effortless spirit and earnest joy only the Golden Age of Hollywood could produce. Michael Curtiz, the most prolific and estimable Warner Bros. director, delivers classical escapism of the highest order, without a shred of irony or cynicism toward the pirate genre. Under his direction, the film progresses with action and romance—a shining example of Hollywood entertainment during the studio heyday. A box-office hit, Captain Blood catapulted the careers of newcomers Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, and it presented a gold standard against which every swashbuckler would be judged. But even while the film represents a prototypical Warner Bros. “A” picture, made with a considerable budget and impressive production values, it’s also evidence of how Curtiz injected realism, energy, and distinct stylistic flourishes into his productions. Film scholars and critics continue to overlook Curtiz as the creative force behind his pictures; many deny him the designation of auteur and prefer to credit him as another workhorse beholden to his studio bosses. However, by considering Curtiz’s origins and views on directing through the lens of Captain Blood’s production, it becomes evident that the director may have been a contracted talent, but he could make even the most straightforward studio assignments distinctly his own.

Before exploring Curtiz’s influence on Captain Blood, detailing the background and history of swashbucklers may better establish their role as a genre standard in early Hollywood. The etymology of swashbuckler dates back to the 16th century and combines the terms swash, meaning strut with a sword, and buckler, referring to a small, circular, and maneuverable handheld shield. Accordingly, the term refers to a certain nimble, performative approach to sword-and-shield combat. In classical literature, the term evolved into a popular form of representation during the age of Romanticism, with adventure texts such as Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819) and Rob Roy (1817); serials by author Alexandre Dumas, including The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers (both published in 1844); and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) and The Black Arrow (1888). Accented by sword fights, prison escapes, sea battles, and romantic derring-do, the genre of swashbuckling adventures continued into a much-loved staple in cinema after the turn of the century. Robert Frazer and Douglas Fairbanks were among the most popular screen adventurers. Both played Robin Hood—the former in 1912, the latter in 1922—though Fairbanks was the more popular of the two. Indeed, Fairbanks would play iconic heroes from d’Artagnan to Don Juan to Zorro, but his days of swashbuckling onscreen were over by the mid-1930s. With its epic-sized production value and an exciting new star, Captain Blood created a new template for swashbucklers in Hollywood.

Set in England in 1685, the story follows a doctor named Peter Blood (Flynn), who’s arrested for treason when he helps a wounded man, a rebel against the despotic King James II. Sentenced to slavery in the West Indies at Port Royal under the cruel Colonel Bishop (Lionel Atwill), Blood falls for the Colonel’s niece Arabella (de Havilland). By treating a case of gout in the local governor (George Hassell) and thereby earning his favor, Blood shields himself from Bishop’s wrath and also earns the protection of Arabella in their mutual, unspoken affection. Still, despising the tyrannical authority of King James II and Col. Bishop, Blood plots a getaway with his fellow slaves and, during a “timely interruption” when a Spanish ship attacks the port, escapes. In the chaos, Blood captures the Spanish vessel and turns its cannons on the raiders, saving Port Royal, ever loyal to England despite the current king and his imprisonment. Along with his band of former slaves who deem themselves a “brotherhood of buccaneers,” Blood forms a pirate clan dedicated to raiding ships in the Caribbean to reclaim their sense of freedom. Though, unlike other pirate clans, Blood’s crew signs an article vowing to remain honorable to women. Meanwhile, Blood yearns for the love he left behind with Arabella, and Col. Bishop takes over as Port Royal’s governor, assigning his ships to hunt Blood on the high seas.

Blood is soon preceded by his reputation for being the smartest man on the ocean, pirate or otherwise. But he makes an error when forming an alliance with another powerful pirate, a French scoundrel, Levasseur (Basil Rathbone). Together, they plan to plunder the seas, until Levasseur captures a ship carrying Arabella and Lord Willoughby (Henry Stephenson), a royal emissary. Threatening to take Arabella as his own, Lavasseur is outsmarted by Blood and attacks him for it. They clash swords in a dance on the beach, which brings Levasseur to his death and Arabella back into Blood’s life. But Arabella chastises Blood over his pirate ways, assuming he’s like other pirates. Though angered about Arabella’s condemnation, he resolves to return her to Port Royal, only to find the French attacking. At sea with his crew for so long, Blood remains oblivious to recent changes: King James II has fled to France, and the newly appointed King William III fights against the French. Willoughby has come to find Blood and present him with the King’s pardon and an offer to fight in the Royal Navy. Blood and the crew accept. They then proceed to defend Port Royal by destroying the warring French ships in a rousing battle sequence. For his effort, Blood is made governor of Port Royal and must decide Col. Bishop’s fate for abandoning his post during wartime to hunt pirates. With this victory, Blood and Arabella finally declare their mutual love and embrace.

Development of Captain Blood began in 1934 when Warner Bros. sought to produce a swashbuckler for star Robert Donat, who had just appeared in a winning adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo (1934) for Reliance Pictures. The studio had acquired the rights to Rafael Sabatini’s 1922 novel Captain Blood: His Odyssey when they purchased Vitagraph Studios in 1925. Vitagraph had bought the rights to Sabatini’s book and produced an unsuccessful, unexceptional silent version in 1924, starring J. Warren Kerrigan and Jean Paige. But the new film presented a potential risk for the Warners. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the studio deemed costume dramas to be box-office poison. Known for edgy crime stories, comedies, and melodramas, the frugal Warners had avoided producing expensive period pieces. However, recent exceptions such as The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) at Alexander Korda’s London Film Productions and Victor Fleming’s Treasure Island (1934) at MGM had demonstrated that historical dramas could make a profit. Moreover, period films could pass the Catholic Legion of Decency—which emerged in 1934 and started to look critically at the contemporary social content of motion pictures—without raising alarms and causing potential delays in production and distribution. Warner Bros. had slated the project with a $750,000 budget that would steadily increase to just under a million during preproduction. Given the projected costs and scale, executive Harry Warner and producer Harry Joe Brown, under the supervision of Hal B. Wallis, assigned Michael Curtiz to the project.

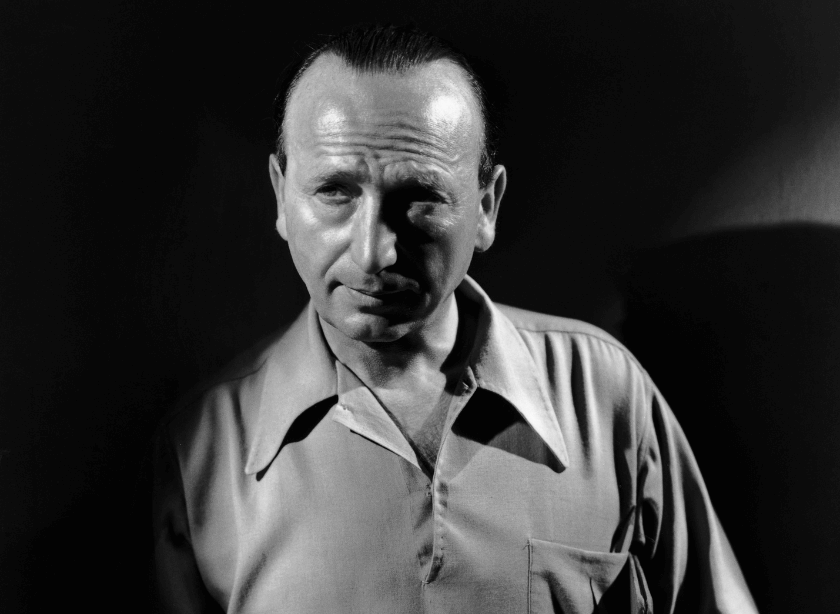

Born in Budapest in 1886, Curtiz started life as Manó Kaminer before changing his name several times over the ensuing years, often to conform to the country where he was working (France, Italy, Denmark, etc.). After a modest upbringing, a stint in the Hungarian theater, and a training period at the German film company UFA, Curtiz began directing for Austria’s Sascha Films, the studio owned by the wealthy Count Alexander Kolowrat. There, he made a name for himself overseeing vast biblical epics and spectacles—productions that required hundreds of extras and elaborate sets that spared no expense. His 1924 release, The Moon of Israel, earned the attention of Hollywood, given its cast of thousands and striking photography with fluid camerawork. Deemed Europe’s equivalent to Cecile B. DeMille, Curtiz found himself courted by Harry and Jack Warner, whose studio was still quite young. Though he was mostly unknown in America, the director arrived in the US in 1926 with dozens of directing credits to his name and the Warners’ promise to give him the capacity to direct Hollywood epics. Instead, the Warners tested Curtiz’s talent on a series of B-grade programmers that he elevated with his distinct visual style. It wasn’t until 1928, when the Warners enlisted Curtiz to direct the monumental Noah’s Ark—with a colossal flood sequence at the climax—that he demonstrated to the Warners his capacity to oversee a profitable epic.

In the ensuing years, the Warners came to depend on Curtiz as their most reliable and profitable filmmaker, attributed to his brutal work ethic, penchant for long hours, efficient planning of his productions, and autocratic approach to directing. Described as a “taskmaster” by those who worked with him, Curtiz also maintained the reputation of having a short temper, shouting broken-English slurs and abuses at his cast and crew when production troubles arose. His thick Hungarian accent amused others who were not on the receiving end. The most famous tale of Curtiz’s behavior remains David Niven’s recollection from the set of The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), another epic starring Flynn and de Havilland. When Curtiz shouted, “Bring on the empty horses!”—referring to horses without riders—everyone laughed, much to Curtiz’s irritation. Niven eventually used the phrase as the title of his autobiography. Similar accounts of Curtiz’s eccentricities, temper tantrums, and language barriers pervade anecdotal Hollywood lore, helping to sketch a gruff exterior portrait without much illumination of the man behind the dictatorial director’s façade.

However, even though many under his direction would never have called him personable, they could not deny his raw skill behind the camera. Olivia de Havilland, who acted in several films for Curtiz, remembered, “Oh, he was a villain, but I guess he was pretty good. We didn’t believe it then, but he clearly was. He knew what he was doing. He knew how to tell a story very clearly and he knew how to keep things going.” Under contract with Warner Bros., Curtiz adhered to the rigorous procedures of the studio system to direct sometimes five or six pictures every year, most of them of low priority and budget at first. It wasn’t until Captain Blood that he became one of the studio’s top directors. Later, he would be trusted with many of the crown jewels in the Warner Bros. catalog, including such incomparable classics as Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), The Sea Wolf (1941), Casablanca (1942), Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), and Mildred Pierce (1945). The list goes on.

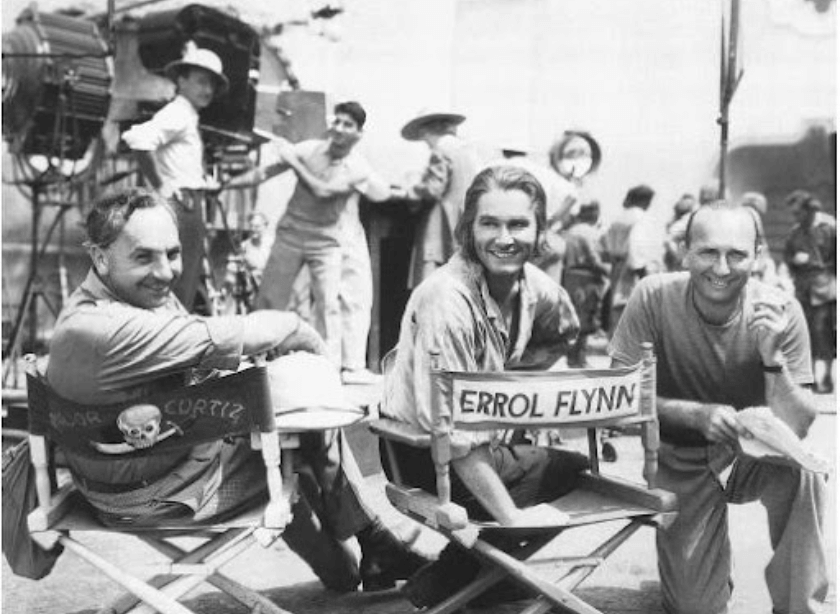

When Curtiz was assigned to Captain Blood, he was excited to oversee a production on the scale of Noah’s Ark again—a film full of action and special effects, and the budget to put forth a spectacle. But Curtiz had four other productions to direct in 1935. This left Wallis and Jack Warner to take on the casting. They originally hired Donat for the lead role. But that fell through when Donat backed out due to his severe asthma, which would make the physical role impossible. James Cagney, Clark Gable, Ronald Colman, Fredric March, and Leslie Howard either turned down the part or couldn’t be borrowed from their respective studios. What happened next was virtually unheard of in Hollywood history. Producer Harry Joe Brown believed Errol Flynn, an unknown Tasmanian-born actor, would be ideal for the role, given his physicality and energy. Brown and Curtiz talked their idea over with Lili Damita, Flynn’s well-connected wife. She was friends with Ann Page, the future wife of Jack Warner. Before long, thanks to Page’s convincing, Warner declared that the unknown Flynn, who had only five small credits, including a minor role as a corpse in Curtiz’s The Case of the Curious Bride (1935), would be cast in the lead role of the studio’s big-budget swashbuckler—the most expensive Warner production in years. Flynn was dubbed an “Irish adventurer-actor” by the Warners’ publicity department, which claimed, “Born three hundred years earlier, Flynn might have turned pirate as easily as he has now turned actor.”

Curtiz would direct Flynn in a total of twelve features, including some of the actor’s best films: The Adventures of Robin Hood, Dodge City (1939), and The Sea Hawk (1940). The studio also regularly cast him opposite de Havilland, a Warner contract player who first appeared with Flynn in Captain Blood when she was just nineteen. Although attracted to each other, Flynn and de Havilland often remained at odds due to the former’s childish pranks and carefree attitude. Even so, they would make nine films together. But on Captain Blood, their clear onscreen chemistry wasn’t yet proven, raising Warner’s financial concerns. Budget projections were over $1 million with Donat as the lead; casting Flynn brought the cost down considerably, but they would surely balloon with Curtiz behind the camera. Curtiz was notorious for making on-set changes to the script and adding whole sequences, which would improve the picture but made budgets impossible to control. For this reason, the director remained a constant frustration to Wallis, who refused to allow any changes to the existing script, adapted by Casey Robinson—later responsible for Now, Voyager (1942) and Passage to Marseille (1944). Wallis and Curtiz would argue over the director’s persistent changes, shooting too many takes, and wasting film stock at the cost-conscious studio. Despite Wallis’ persistent hounding, Curtiz ignored the complaints and shot the film how he saw fit.

In the early weeks of filming, Flynn’s unproven skills in front of the camera left him shaking with nervousness. Curtiz berated the actor’s performance in the early dailies; his approach to actors was to treat them like part of the cinematic apparatus—tools that, when they didn’t function, deserved to be worked over. Flynn’s initially rigid acting and greenness as a leading man eventually loosened during the shoot. Eventually, the visibly tense actor was coached in his first starring role by Curtiz, on order from Wallis, telling the director to “work with the boy.” Flynn improved so much that scenes shot with the actor early in the shoot were refined and reshot by Curtiz near the end of production, after everyone agreed that Flynn just needed time to gain his onscreen confidence. Once attained, Flynn’s self-assurance fueled his natural charm and agility, so that the result seems like the performance of a longtime star and screen hero. Additionally, Flynn performed many of his own stunts, which the original Captain Blood pressbook is quick to point out—along with a tall tale about how Flynn saved de Havilland from drowning during the production, creating an offscreen hero myth.

By the time all the reshoots had been completed, the budget was back up to nearly a million. Filming the bravado battle scenes with life-sized ships, miniatures, process shots, and footage from the 1924 silent The Sea Hawk (not to be confused with the 1940 Curtiz-Flynn collaboration of the same name), Curtiz captured the action sequences with swift camera movements and active compositions. The production required a massive technical crew and reportedly two months of shooting to complete the climactic battle sequence between Blood’s crew and the two French ships. All the while, Curtiz ignored Wallis’ input and, instead, shot fast and trusted his instincts. Filming took place on some actual locations, along with soundstages reinforced with elaborate set designs and matte paintings. Adding to the production, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, an opera composer who would go on to create iconic scores for The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939), wrote his first music for the cinema. Korngold adds a vital element to the film with his score, using Warner’s industry-leading music department that became home to Hollywood’s greatest musicians at the time, including the prolific composer Max Steiner. Korngold’s memorable score carried along the production, which went on to earn $2.7 million at the box office, ensuring a huge hit for Warner Bros. and five Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Sound Recording, and Best Musical Score).

Although the Warners felt the film was too long at 119 minutes, Captain Blood’s success affirmed Curtiz’s place among the studio’s top directors. The prolific string of collaborations between Curtiz and Flynn to follow supplied Warner Bros. with their most successful films in the coming years. Both artists proved their versatility by making period epics, romances, Westerns, still more swashbucklers, and even a comedy together. Yet their partnership was not a pleasant one, as Curtiz’s on-set rage proved intolerable, and Flynn was hardly the type to back down from confrontation. After one argument brought the two to blows, Flynn made sure the two would never work together again. Their last film together was the air force medical drama Dive Bomber from 1941. So the question remains: Why was Curtiz such a tyrant? By all accounts, he compartmentalized his personal life and focused on the job, working tirelessly. He hated downtime away from a shoot and took fewer vacations than his fellow directors. And so, the director’s offscreen persona was impossible to construe outside of his obvious professional devotion to the assigned picture. What stimulated his ever-constant tension during production remains a mystery, aside from his drive for perfection. The few biographies written about him tend to focus on his work ethic and the quality of the end product. To be sure, his commitment to making quality films extended to a notorious lack of consideration for his cast and crew, including some unfortunate deaths caused by stunts gone bad in the name of realism.

Still, given the factory-like nature of Hollywood’s studio system, it remains a challenge to call Michael Curtiz an auteur. How could a journeyman, regularly forced to direct whatever project the Warners demanded of him, imbue his productions with a consistent authorial voice? Critic Andrew Sarris wrote in his prominent article “Notes on the Auteur Theory,” the Americanized answer to François Truffaut’s original auteur treatise in Cahiers du Cinéma, that he believed Curtiz to be little more than one of “Warners’ technicians.” And while Sarris admitted Casablanca was the director’s masterpiece, he argued, “If many of the early Curtiz films are hardly worth remembering, none of the later ones are even worth seeing.” Looking at Curtiz’s filmography and seeing Angels with Dirty Faces, Dodge City, The Sea Wolf, Mildred Pierce, Flamingo Road (1949), Young Man with a Horn (1950), White Christmas (1954), and King Creole (1958), among many others, how does Sarris wave off this ongoing roster of classics and conclude that the director was merely a functionary for the studio who lacked any artistic influence over his productions? Perhaps Sarris’ view stems from Curtiz not playing the self-obsessed creator card like so many auteurs he references in his article.

Curtiz was not a writer-director, nor did he develop many of his own projects or inject a worldview into his films. Furthermore, the filmmaker was not known for his candid discussions about his perspective with either film scholars or the press. He also refused to write an autobiography, hence, like many early filmmakers who died before film theory became a vast subject of intellectual curiosity, his personal philosophy on directing is unknown. However, early in his career, Curtiz argued for a version of the auteur theory, suggesting, like many of his European-born contemporaries, that a film’s director stands at the helm of a production. He famously compared the frame, complete with players and setting, to an unfinished canvas on which it was the director’s task to compose like a painter. Curtiz remarked in a 1913 issue of Motion Picture News, “It is the director who makes the film happen in his humble ways. Building up the scenario invisibly, he brings it to success, he makes the actors famous—even the unknown ones—while he himself remains a no-name entity because in the row of the movie theater, the viewer cannot comprehend how a film is made.” Curitz was not a puts-his-name-above-the-title director like John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, or Howard Hawks. But he argues that “the ultimate responsibility rests on one man’s shoulders: the director’s.”

Alan K. Rode, film scholar and author of Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film, argues that Curtiz had the attitude of an auteur, even if he didn’t have a consistent set of themes that he regularly infused into his films—largely because, working at Warner Bros. for the majority of his career, he was required to direct whatever scripts he was given, with only the rare option to deny certain projects. Rode writes that, early in Curtiz’s career, “He harped on the notion that the director was the essential creative artist. His early magazine articles detailed the essence of the auteur theory a full five decades before Cahiers du Cinéma and the film critic Andrew Sarris made it popular.” Indeed, Curtiz believed directorial vision was crucial to making a successful film, driven by “a leadership that is solely in the director’s hands,” and not, for instance, left to actors or even the studio. Additionally, he believed his Hollywood films were his, though they actually belonged to Warner Bros., which refused directors artistic license that included changes to scripts already approved by the studio. Yet, in each film, Curtiz sought to apply his stylistic touches, from distinct angles and shadows inspired by German expressionism to a vitality that allows his productions to move with effortless momentum. And so, how unfortunate that Sarris identifies Curtiz as some studio cog, lifelessly turning out one product after another on the Hollywood assembly line—especially when considering so many of the director’s signature techniques that significantly advance his screen stories.

Where the dilemma emerges with Curtiz is his willingness to make whatever the studio asked him to direct, and then through his compliance, he becomes the top director for the Warners. Furthermore, his style proves difficult to pinpoint because he refused to reduce himself to a particular “type” of film. By contrast, Hitchcock had wrong-man thrillers and tales of the macabre, branding him the Master of Suspense. But Curtiz could and did make anything, regardless of genre or tonality, thus his individuality within a production is more difficult to identify. He made swashbucklers, screwball comedies, musicals, Westerns, film noirs, gangster movies, melodramas, and horror pictures. So, it is perhaps simplest to describe Curtiz as an exception to the auteur theory, a master whose chief drives were the speed, quality, and financial practicality in which his films were made. This equation, however unaligned with Sarris and Truffaut’s limited definitions for screen artists, nonetheless identifies Curtiz’s undeniable gift as a filmmaker.

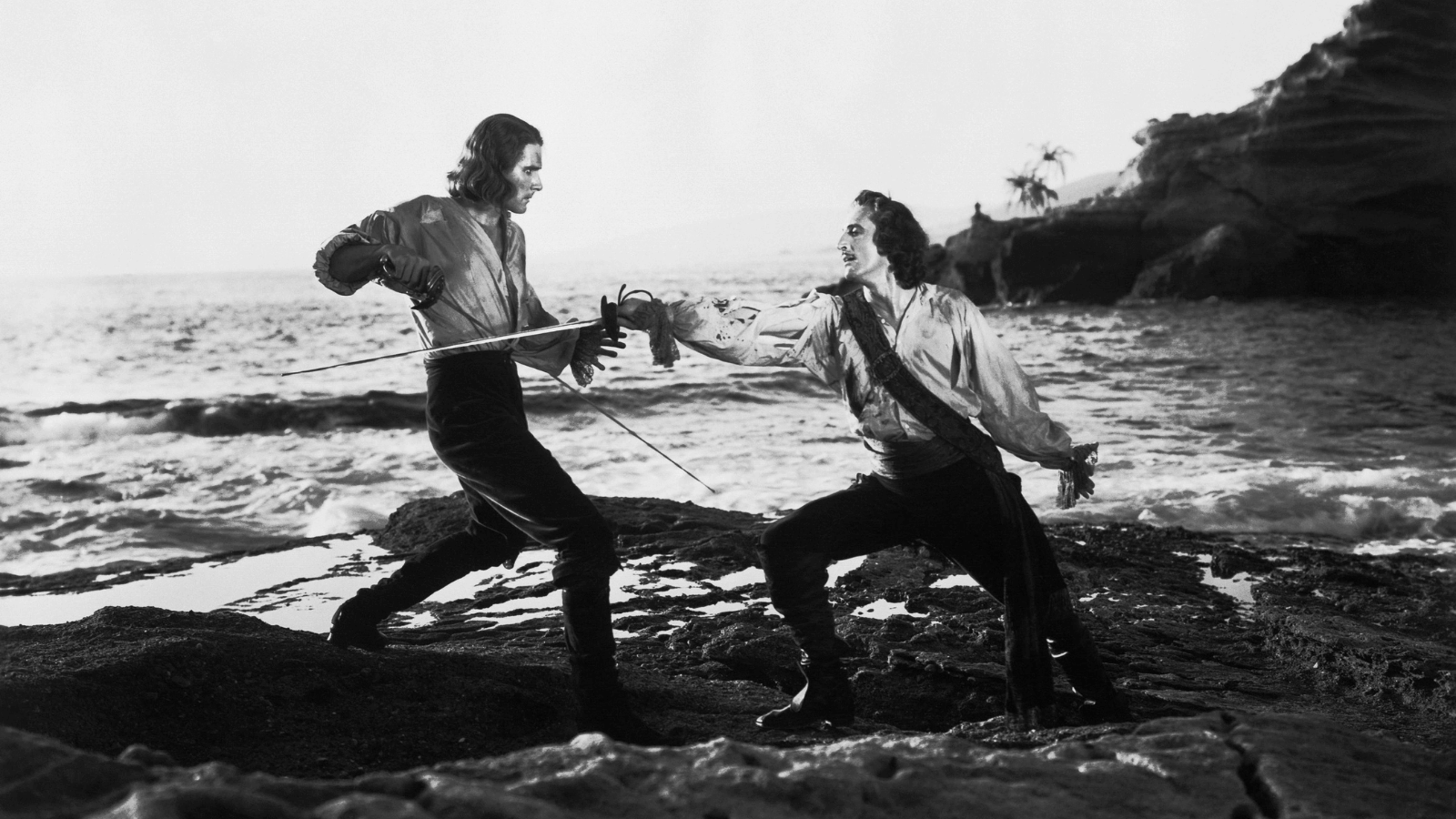

If there’s a constant theme among all of Curtiz’s productions, it’s that his presence behind the camera immeasurably improved them. Captain Blood is a perfect example of this. Rode observed that “depicting realism at all costs became [Curtiz’s] directorial mantra,” sometimes to the detriment of his cast and crew. This is evident throughout many of the still-convincing elements of Captain Blood. During the sword fight between Blood and Levasseur, Curtiz wanted to see the fear of death in the actors’ eyes on film, so he removed the safety cap from the end of the swords, making Flynn and Rathbone duel without protection. Curtiz refused to shoot the sequence in the studio; he filmed on the rocks at Laguna Beach, allowing the crashing waves to punctuate the violent struggle. The actors engaged, following the innovative fight routine sketched out by legendary swordplay expert Fred Cavens, who later arranged the sword fights in The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk. Rathbone, an experienced fencer who had taken a particular dislike to Flynn, left a scar on his costar’s arm. But never had audiences seen such an intense onscreen clashing of swords, and that was Curtiz’s priority, however unsafe his methods.

Curtiz’s visual signatures appear throughout Captain Blood, even if they were overlooked by Sarris. The director creates a dynamic understanding of space, giving the viewer a clear impression of the environment. His camera pushes in to emphasize dramatic potency or yearning, and then it pulls away to signify isolation and rejection, sometimes within the same take—other filmmakers would just cut between the medium shot and the close up. But Curtiz activates otherwise staid scenes by projecting massive shadows of vegetation or soldiers onto blank walls, inscribing every shot with vibrant lighting and realistic details. Additionally, the entire story is told with an air of sophistication through Robinson’s clever dialogue. Blood, described as having a “rascally mouth,” is given a sharp tongue to match his intelligence, and Flynn captures the hero’s defiance of authority in scampish and intense expressions. Curtiz also emphasizes how Blood and Arabella always seem to have two conversations, one with their words and another with their eyes, and the charisma between Flynn and de Havilland is palpable. The director deploys every tool in his considerable kit, putting everything onscreen into a composed harmony. And though not qualifying for every statute inscribed in the subjective limitations of the auteur theory, Curtiz’s approach remains that of an impeccable craftsman whose work can be easily identified next to other filmmakers of his time—his work is not entirely selfless and impersonal, as that of other studio-contracted directors.

Setting aside Curtiz’s influence on Captain Blood, both the film and its star have been replicated to no avail by subsequent swashbucklers. The Black Swan starring Tyrone Power from 1942 and even Curtiz’s own The Sea Hawk lift from the director’s design. Indeed, never was there a Hollywood pirate film that failed to look back to Captain Blood for inspiration. Even modernish swashbucklers such as Cutthroat Island (1995) and Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean series reach for the kineticism of Curtiz’s filmmaking and the effortlessness of Flynn’s performance, without ever attaining the simplicity and acumen of the 1935 original. These later films always wink into the camera with a sense of satire, whereas Captain Blood succeeds wonderfully on its own spectacle. Throughout, the thrills never cease, from the beach duel between Flynn and Rathbone to the impressive final ship battle. Cannons roar, and pirates swing on rigging to enemy ships, fast-paced swordfights clang, while Blood shouts rousing words to his buccaneers. Flynn exudes all the traits of the real thing, jumping into combat with that signature spring in his stride. Sweeping camera movements catch this action, just as more delicate moments are supplied the necessary affection. Arabella’s contrasting fascination yet frustration with Blood’s quest for freedom is captured in delicate, soft-filtered shots that highlight de Havilland’s beauty. And when the characters embrace, de Havilland places a kiss on Flynn’s cheek, as sweet a moment as any Golden Age picture could offer. These are moments made sublime by Curtiz’s expert handling and suggest he was much more than the “workhorse” label assigned to him.

Emblematic of Curtiz’s most landmark directorial efforts, those with actionized narratives that highlight his vigorous camerawork and lively direction, Captain Blood belongs in the pantheon of great swashbucklers. Its timeless entertainment value and romantic appeal remind us why Warner Bros. was the studio for action, why Flynn became the era’s greatest action star, why de Havilland earned so much respect for her screen presence and skill, and why Curtiz would continue to be trusted with the studio’s most prestigious productions. And even though Flynn and de Havilland resented having to make additional pictures with Curtiz, their many subsequent collaborations suggest that Captain Blood was the beginning of a historical film legacy. Often imitated but never matched, the film would become a blueprint for every pirate picture to follow, though few have ever reached its heights. Curtiz’s influence is evident throughout the film, making Captain Blood both a studio production and the clear outcome of its director’s efforts. Whether or not Curtiz deserves to be called an auteur proves debatable and, in the end, meaningless next to his unmistakable influence on the film.

Bibliography:

Flynn, Errol. My Wicked, Wicked Ways: The Autobiography of Errol Flynn. Third Woman Press, 1987.

McNulty, Thomas. Errol Flynn: The Life and Career. McFarland, 2004.

Robertson, James C. The Casablanca Man: The Cinema of Michael Curtiz. Routledge, 1993.

Rode, Alan K. Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film. University Press of Kentucky, 2017.

Rosenzweig, Sidney. Casablanca and Other Major Films of Michael Curtiz. UMI Research Press, 1982.

Sarris, Andrew. “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” Film Theory and Criticism, ed. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 515-518.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. Pantheon, 1988.

The Adventures of Errol Flynn. Dir. David Heeley. Prod. Top Hat Productions, Turner Classic Movies (TCM), 2005

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review