The Definitives

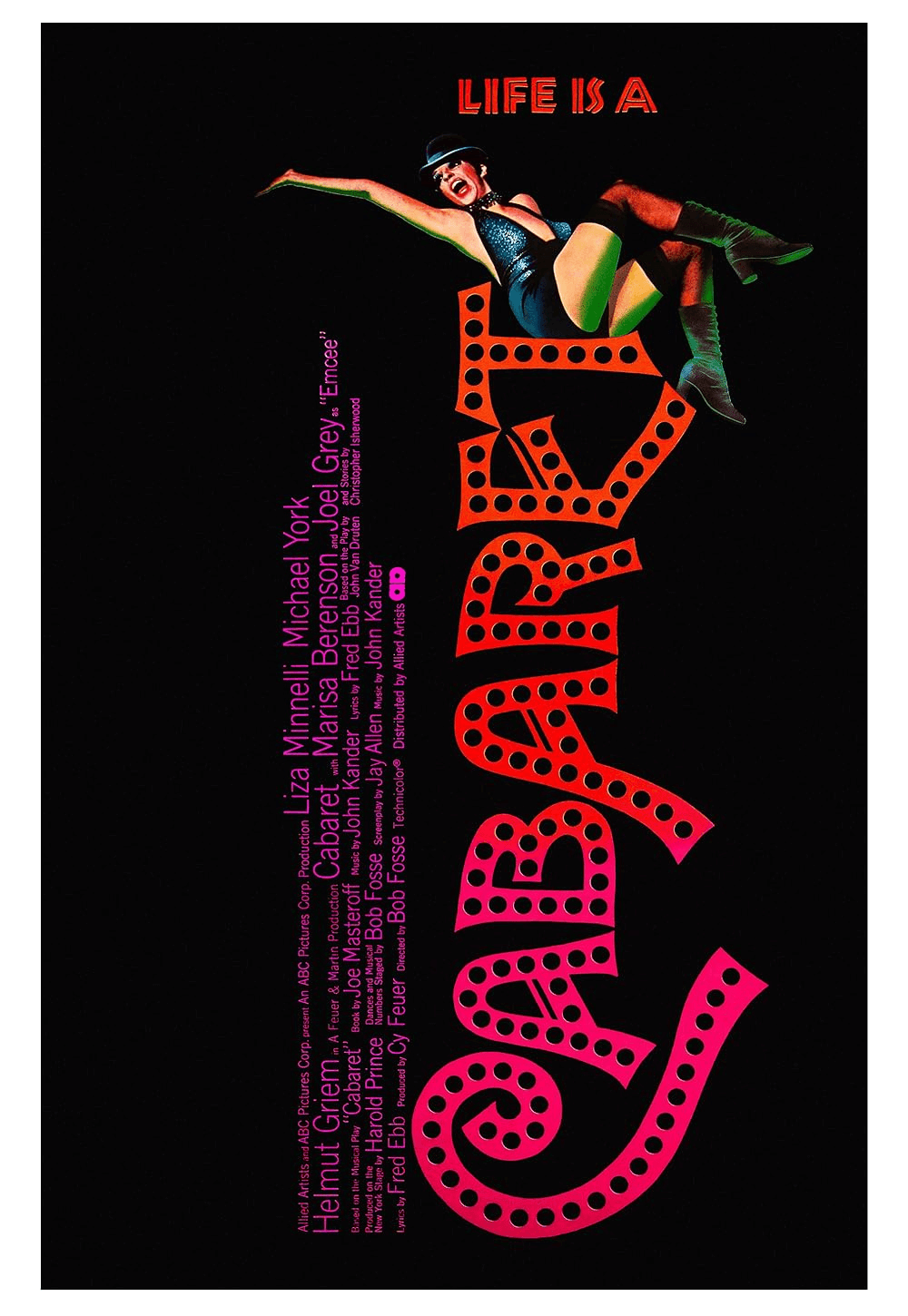

Cabaret (1972)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Cabaret changed everything audiences knew to be true about movie musicals in 1972. Set in the Weimar Republic of 1930s Berlin, a period soon overshadowed by fascism, the film contrasts its grim backdrop with a darkly playful style. The dynamic was fostered by director Bob Fosse, who indulges in sexual liberation, garish camp, and historical irony above all. Tinged by obscene buoyancy and the acrid scent of the atrocities to come, the film alternates between realistic scenes with the romantically entangled characters and the rise of Nazism. Both are reflected by stage performances inside the seedy Kit Kat Klub, a Berlin nightspot specializing in tawdry songs and delightfully tasteless humor, where the diabolical Master of Ceremonies encourages his spectators to revel in its sleazy pleasures. The licentiousness and excess inside supply distraction and feed denial, producing a cautionary tale about how self-gratification can distract from the malicious forces attempting to manipulate those impulses to suit their depraved agenda. The film resolves that, whether living inside the performative joy of a cabaret or forcing change through political violence, both represent twisted illusions and self-denial on a disturbing scale. These were radical ideas for a movie musical.

Far from the carefree musicals Hollywood had produced to that point, Cabaret confronts its audience with how their reality is analogous to the Weimar Republic—what historians have described as Europe’s Babylon, an association that implies its eventual fall. One reason Fosse’s film struck a chord with audiences in 1972 and remains relevant under today’s fascistic regimes is the setting’s innate relationship between personal freedoms and political oppression. The characters engage in uninhibited thinking, frank discussion of “screwing,” gender-fluid fashion, abortion, and excesses, even as the mounting Nazi threat promises to quash such behavior. At one point, a patron of the club kicks out a Nazi for dissenting, only to be cornered and beaten later by a gang of brownshirts. How fitting that Fosse made the picture during sociopolitical turmoil in the United States. The volatile 1960s ended with a string of assassinations, racial violence during the Civil Rights Movement, and Richard Nixon’s presidency. Similar concerns emerged in the 1970s, such as sexual and women’s liberation, abortion access, a rise in recreational drug use, and continued political scandals—trends that clashed with the conservative interests of the religious right.

Fosse sought to distance his film from the unreality of Hollywood musicals to augment the contemporary relevance of Cabaret. In part because of the story’s unlikely setting for a movie musical, he downplayed the musical-ness of the production to avoid neutralizing its message. Some moviegoers struggle to reconcile how musical characters unnaturally break into a performance to express themselves, robbing the material of its meaning. Fosse was among them. Even though he contributed to and lionized Hollywood musicals in the past, particularly those of his idol, Fred Astaire, he told New York Magazine in 1974 that bursting into song at random conveyed “a removed reality. The movies bring that reality closer.” Fosse wasn’t alone in his views. The musical had changed in the mid-twentieth century. Astaire-brand musicals in which characters break into song for no reason whatsoever were being replaced by Oklahoma! (1955) and West Side Story (1961)—wherein songs emerged from the story. Given the historical and thematic severity inherent to Cabaret, Fosse wanted to avoid the frivolous tonality of traditional musicals. His approach was an evolutionary step forward, with musical numbers that all took place within the diegesis—on the stage in the Kit Kat Klub, situating the narrative’s events in reality and preventing the viewer from escaping into movie magic.

Cabaret’s juxtaposition of these polarized forces, the performances in the nightclub and the rise of Nazism in the Weimar Republic, color the narrative, suggesting the freedoms inside this private world won’t survive the looming wave of fascism. The story opens with the arrival of Brian Roberts (Michael York), a Cambridge scholar of philosophy working on his PhD. Brian befriends and begins an affair with an insatiable, cocaine-sniffing nightclub singer, Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli). Trapped in the eye of her hurricane energy, Brian finds her maddening but cannot resist being swept along. Their association tests the limits of socially acceptable relationships of the era, a reality that becomes clear when they welcome another party into their eventual coupling. Elsewhere, in a tender subplot, the film highlights the tenuous courtship between Brian’s English-language pupils, Fritz (Fritz Wepper), a Jew pretending to be a Gentile, and Natalia (Marisa Berenson), who hails from a wealthy Jewish family. Their tenuous courtship leads to a marriage. They disappear from the film late in the proceedings—not because Fosse has forgotten about them, but because their absence suggests a grim fate.

Fosse worked closely with editor David Bretherton to intercut the dramatic scenes with musical numbers performed on the stage, presenting a rare musical where the songs and dancing occur as part of the story. Fosse and Bretherton also related each song with the dramatic events outside, a technique that would weave songs from the club or one performed at an impromptu Nazi rally in a Biergarten into the narrative fabric despite their spatial separation. The Kit Kat Klub sequences also convey what many of the dramatic scenes do not: the sleazy decline of a joint that, perhaps a decade earlier, may have been a must-see nightspot. As a result, Cabaret evokes an overwhelming sense of melancholy about a society on the downswing, oppressed by forces that rob people of their freedoms. One cannot hear the lyrics “It was a fine affair, but now it’s over” from the song “Mein Herr” without weighing the end of an era—whether that end arrived in the 1930s, for moviegoers in the 1970s, or for audiences watching in the 2020s. The recurrence of fascistic leaders means Cabaret will remain a vital text for examining how political forces stomp out individual liberties and freedoms.

The Kit Kat Klub sequences operate similarly to a Greek chorus, commenting on and reflecting the story proper—set in a world of disparities, heightened behavior, and historical foreboding. The permissive behavior inside has a complex relationship with Germany at large. It is both a distillation of and a sanctuary from the outside. The unrestrained behavior and risqué songs also represent a carryover from earlier in the decade. With their end signaled by the emergence of Hitler’s zealots, the club performers cling to their freedoms, occupying a tenuous in-between space, reflected by their marginalized status in Berlin and the narrative. Consider how the first image is a black-and-white close-up of the club reflected in a warped metal wall, like a distorted funhouse mirror. The opening credits play with no score, only this indecipherable image that implants uncertainty of what comes next—the prevailing feeling throughout Cabaret. As the monochrome transitions into full color just as “Directed by Bob Fosse” appears onscreen, Joel Grey’s sinister Master of Ceremonies (hereon Emcee) first appears, establishing the uncanny mode in which most of Cabaret operates.

The Emcee’s first song, “Willkommen,” introduces the viewer to a seductive if nightmarish host. Looking directly into the camera, this seducer and corruptor invites the audience to “leave your troubles outside.” Out there, the KPD (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, or Communist Party of Germany) vandalizes Nazi posters, and fascists kill people in the streets. But the Emcee wonders: Why think about such things when you could be enjoying the club’s diversions, a horny assemblage of racy songs and no inhibitions? Among them are gender-fluid musicians and performers, most of whom look run down and tired, their pale makeup accenting the dark circles around their eyes, their clothes glitzy yet worn. Even so, the Emcee insists everyone inside is “beautiful”—the girls, the orchestra, and life. Take the idiosyncratic Sally, whose nocturnal appetites feed an exhausting life of “fine decadence,” as she calls it. She appears happy and moves with the whirlwind energy of someone unfazed by her surroundings. But her spidery mascara, taste (and need) for prairie oyster cocktails for hangovers, and pale complexion tell another story. They conceal a wounded interior, marked by an absent father whose approval she seeks. Above all else, she wants to become a movie star in the German film industry, and she spends many nights interviewing with producers or studio execs, hoping to sleep her way into her big break.

The hedonism of Cabaret runs rampant, but it’s often tinged with something darker—sometimes vile, sometimes tragic. The Emcee embodies this duality, channeling a strain of decadence unique to showbiz, where mockery and detachment blur moral boundaries. Pauline Kael aptly described his provocative performances, mocking himself, others, and even anti-Semitism, as “camp carried to its ultimate vileness.” Grey’s obscene grins signify the indulgence of the Weimar Republic and hint at the looming fascist undercurrents spilling into the streets. Caught in his orbit, Sally is willing and venal, yet also tragic. She delights in such behavior out of a persistent need for rebellion and attention, whether performing or testing the limits of Brian’s inexperience. For his part, Brian has never met someone so unfiltered and passionate. After two days, she declares Brian her best friend—a sign of her impulsive nature and lack of real friends in Berlin. She’s used to men “pouncing” on her, so when Brian rejects her initially, she wonders whether he’s queer. He responds with characteristic British reservation, admitting that his experiences with women have been fraught with disappointment, leading him to question his sexuality. Given their shared frustrations, she teaches Brian to release pent-up emotions by screaming when an elevated train passes overhead. It’s one of the only moments when Sally doesn’t disguise herself. Another is when Sally wonders, “Maybe I am just nothing,” and breaks down in tears. Brian consoles her with a kiss—an act that awakens his sexuality and sparks their love affair.

When Sally sings “Maybe This Time,” a ballad about her persistence despite ongoing professional failure, to an all-but-empty and indifferent club, it’s an aching, hopeful declaration of her artistic prospects. It’s also the song that aligns most with Fosse, who was always trying to prove and re-prove his merits as a performer, choreographer, and director. Although most film historians and biographers deem All That Jazz (1979) the critical text to understand Bob Fosse, Cabaret circumvents the author-as-subject factor that makes his autofictional Palme d’Or winner so much about the man, the myth. Part of what makes Cabaret timeless is that Fosse does not set out to satiate his ego, at least not regarding the subject matter. Fosse had something to prove with Cabaret; however, he became fixated on more than just the film. In 1972 alone, Fosse directed Cabaret to massive box-office success and critical acclaim in February; given its popularity, he directed Liza Minnelli in a rare television concert movie, Liza with a Z, for NBC in September; and he bowed Pippin on Broadway, which he directed and choreographed, in October. That year earned him an Oscar for Best Director, three Emmys, and two Tonys. Each production showcased Fosse’s distinct blend of classical showbiz spectacle with sensual, punchy dance moves found in burlesque. While focusing on technical skill and artistry worthy of Astaire, Fosse cut through the charm and elegance with his modern flourishes, expressionist movements, and sordid undercurrents.

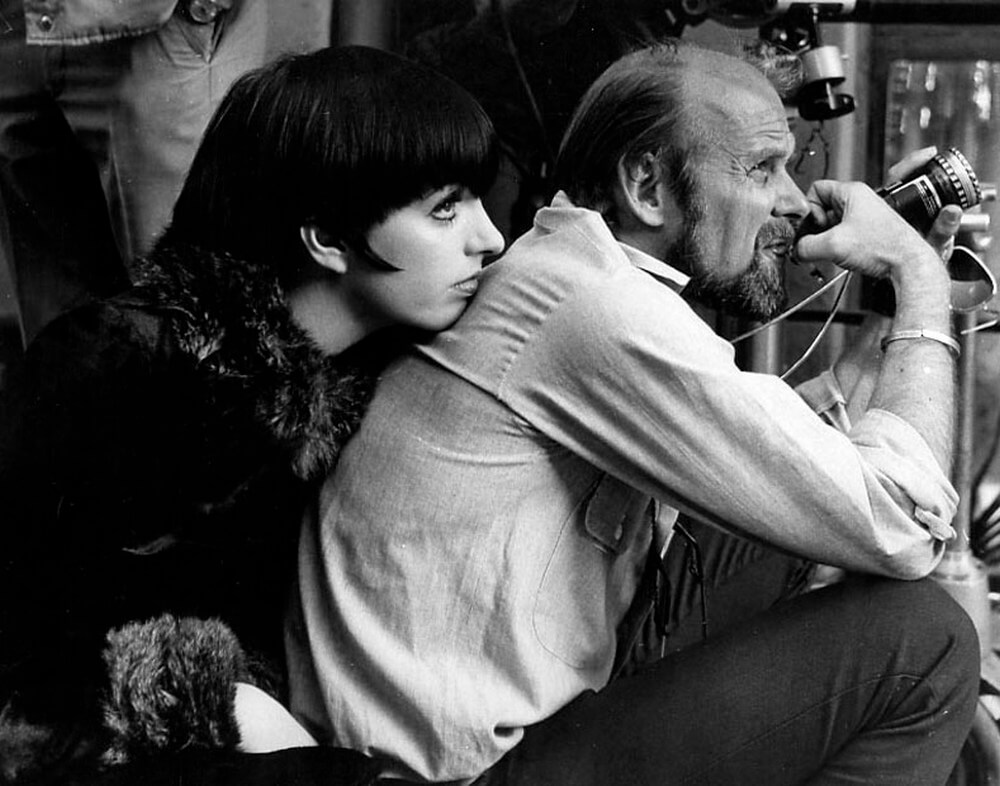

When Fosse maneuvered his way into the director’s chair of Cabaret, he had only directed one other picture, Sweet Charity (1969), based on his Broadway production. The stage version starred Gwen Verdon, his wife, in a Neil Simon-penned adaptation of Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (1957). The screen production replaced Verdon with a studio-approved star, Shirley McClaine, who struggled with Fosse’s demanding choreography, and, like many candy-colored musicals of this era, such as Star! (1968) and Paint Your Wagon (1969), flopped at the box office for its saccharine worldview in otherwise grim times. The critical and commercial failure of Sweet Charity stalled Fosse’s meteoric rise to that point. He had thoroughly established his style with moves and gestures so distinct that they served as his signature—the downturned bowler hats, finger snaps, props, back bumps, chairs, and sensual gyrations. His early work as a 13-year-old dancer performing in unseemly nightclubs implanted his lifelong embrace of burlesque moves. The experience had left him with psychological scars, preoccupations, and troubled relationships too, but it ingrained his knowledge of technical dance, vaudeville performance, and showmanship.

Fosse brought the skill he learned in adolescence to the US Navy’s entertainment division before singing and dancing his way to Broadway. He performed onscreen in a few Hollywood musicals in the early 1950s, and he quickly learned his talents were best applied behind the camera. Fosse soon began directing and choreographing on Broadway, amassing a reputation for blockbuster shows and earning several Tony Awards along the way. But it was his choreography on The Pajama Game (1957) and Damn Yankees (1958), the two big-screen adaptations of the stage productions he mounted in New York, that earned him a chance to direct his first feature. Had Sweet Charity not been deemed a mild disaster, which profoundly stung Fosse’s already fragile sense of self, he wouldn’t have been so motivated to make Cabaret something special—to prove himself again. Stricken with a chronic inferiority complex and insatiable desire to create something meaningful, Fosse sought to blend Cabaret’s germane themes with his precision dance into a work of art worthy of his name—not another lighthearted musical but an unflinching look at fascism, intolerance, sexuality, oppression, and politics.

The story of Cabaret appeared in several other forms before the movie musical. The material began with Christopher Isherwood, the openly gay writer of The Berlin Stories, a 1945 anthology featuring two earlier novels, Mr. Norris Changes Trains (1935) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939), and the novella Sally Bowles (1937). The young author wrote about his experiences as a British émigré in the Weimar Republic, presenting a fictionalized version of himself, named Chris, thusly: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.” Capturing the uneasy political climate during the early 1930s and the escalating antagonism Nazis demonstrated against Jews and Communists, Isherwood charted how the debauched bohemian flappers and unbridled tenor of the 1920s was being replaced by the swelling boil of fascism and intolerance. A real-life cabaret dancer named Jean Ross inspired Isherwood’s most famous character, Sally Bowles, the sexually liberated performer who sings in salacious lounges, drinks prairie oysters, and obtains an abortion—all to the shock of contemporary readers. Bowles and several other Isherwood characters appear in John van Druten’s 1951 play I Am a Camera, which screenwriter John Collier and director Henry Cornelius adapted into a film in 1955, starring Julie Harris as Sally and Laurence Harvey as Chris.

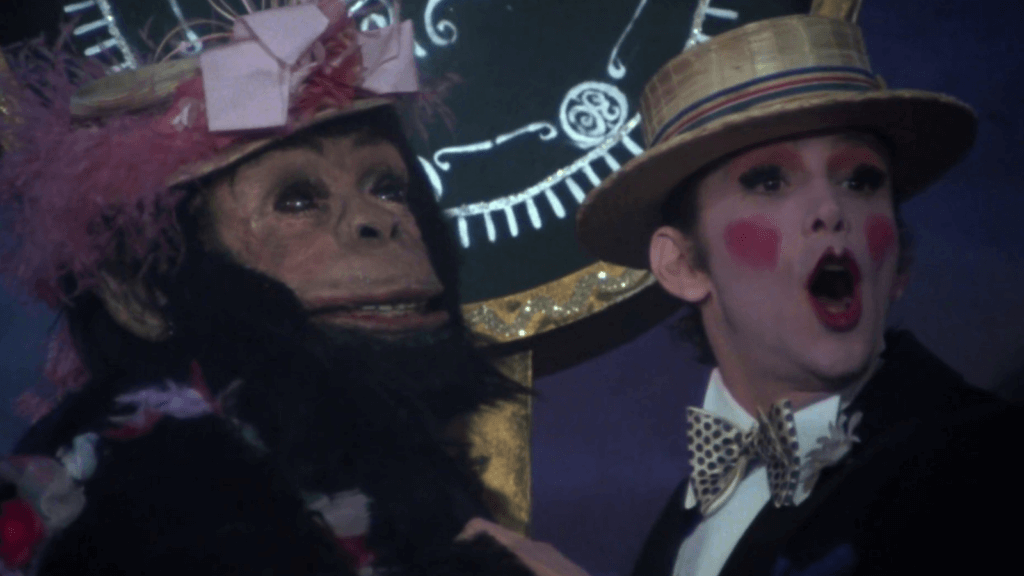

Isherwood and van Druten’s texts inspired the 1966 stage musical. Producer Harold Prince purchased the rights to The Berlin Stories and I Am a Camera and commissioned Joe Masteroff to adapt and John Kander and Fred Ebb to write the music, focusing on the story first. In the musical version, Sally and Chris (renamed Cliff) return, with the former occupying Isherwood’s more downtrodden description of Sally: “She sang badly, without any expression […] yet her performance was, in its own way, effective because of her startling appearance and her air of not caring a curse what people thought of her.” The musical’s score owes much to what Adolf Hitler deemed the “degenerate art” of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, particularly their 1928 play The Threepenny Opera, with satiric socialist themes designed to emphasize the failure of capitalism. Directed by Prince, the Tony-winning stage version introduces the Kit Kat Klub, an amalgam of the Troika and the Lady Windermere from Isherwood’s book, two nightspots known for joyful promiscuity and jazzy numbers. The musical also invented the Emcee, whose leering eyes and mischievous manner epitomized the grotesque reality of, or satirized, the Third Reich. Either way, he made co-conspirators out of anyone who watched—you’re either delighted by his debauched critique or entertained by his repulsive reflection of the Nazis.

After the screen rights to the stage musical passed from Cinerama to Allied Artists (AA), Cabaret landed with ABC Pictures Corp. producing and Allied Artists distributing. Cy Feuer, Fosse’s friend who, like Fosse, had dabbled in Hollywood (as an Oscar-winning composer) and earned Broadway fame with a string of celebrated productions (including Guys and Dolls), was tasked with producing the screen adaptation for ABC and AA. However, Fosse’s track record on Sweet Charity made Feuer’s superiors hesitant to hire him. Feuer offered the job to Prince, who directed the stage version but turned down the film. Then he approached Gene Kelly, Joseph Mankiewicz, and Billy Wilder, who also turned it down. Finally, Feuer appealed to the decision-makers on behalf of Fosse and secured him the job directing Cabaret, working from a script by Jay Presson Allen with significant contributions from Fosse. The studios figured Feuer would keep an eye on Fosse, who, the producer assured them, would be careful not to risk making another over-budget flop that would put his directing future on the line. But they didn’t know Fosse, who fought his producer for more time, more money, and his Sweet Charity cinematographer Robert L. Surtees. The former two he got; the latter, he didn’t.

The producers wanted Geoffrey Unsworth instead. Fosse would hardly be slumming with their choice; Unsworth shot Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and later Richard Donner’s Superman (1978). However, any rational negotiation between Feurer and Fosse over the issue was ruined when the director eavesdropped on his producer, who spoke to the head of ABC and vowed to keep Fosse under control and deny him Surtees. Fosse confronted Feurer, calling him a “two-faced shit,” and the resulting conflict forever tarnished their friendship. Still, Feurer secured Fosse a $3 million budget and a shoot in Germany at Bavaria Atelier Gesellschaft Studios. That suited Fosse, who preferred to be away from Hollywood, away from the prying eyes of studio execs. The choice to film in Germany also provided verisimilitude with real location shooting and minimized budgetary strain from the cheaper cost of filming in West Berlin. Fosse also enlisted Verdon to assist. Many German clothiers had discarded wartime garb to either forget about or heal from World War II. Verdon traveled to Paris antique shops to find Sally’s signature stage outfit and to New York to locate a convincing gorilla costume for the “If You Could See Her” number. Besides offering Fosse all manner of advice and support on the set, she also taught the cast to melt a crayon in a spoon and apply the wax with a mascara brush, achieving that look of cheap, thick lashes that fit the era.

Much like Fosse, who had a vested interest in the production for his future artistic legitimacy, Minnelli had something to prove. That’s part of why Fosse cast her as Sally Bowles. The daughter of Judy Garland and director Vincente Minnelli, two icons of Hollywood musicals, Minnelli had appeared in a few movies and stage productions. However, she turned down several full-blown musicals and Disney movies until she could measure up to her mother. The performance, inspired by photos she found and admired of Marlene Dietrich’s garb and Louise Brooks’ hair, transcends Minnelli’s influences to create something altogether new, turning “Liza” into a household name—and, like her mother, a queer icon. But Minnelli’s Sally is neither the Sally from Isherwood’s novella nor the stage productions; in both iterations, the character was a little sadder, a bit more downtrodden. Liza made the role her own, injecting what became her signature energy into every gesture and emotion. She earned an Oscar for the role precisely because she redefined it, channeling Garland, Dietrich, and Brooks, while arriving on the screen with the ferocity and fusion of a star.

Grey, whom Fosse insisted on casting, had already earned a Tony for playing the Emcee; he, too, would win an Oscar for his entertaining yet chilling presence. But Fosse knew the performance couldn’t be identical to the stage version, given the proximity of the camera. To enrich the performance for the screen, Fosse and Grey worked out a set of loaded glances, facial gestures, and flapping tongues that hint at a prior sexual relationship between Sally and the Emcee. Grey amplified every sleazy trait to heighten the jovial corruption festering beneath the club’s surface. However, often overlooked is York’s performance of carefully played sexual ambiguity. Initially, York found Brian a dull, passive character and voiced his concerns to Fosse. For his part, the director worked with his male lead to improve Brian Roberts, a character developed out of Chris in The Berlin Stories and I Am a Camera and Cliff in the stage version. The character was gay in the original text, as Isherwood was; he was portrayed as heterosexual on the stage. In the film, Fosse and York made him an unspoken bisexual. York looks back at his time with Fosse as one of his most enriching collaborative experiences, given the director’s willingness to improve the character so deep into the production process.

Fosse sought to strip away the polish from the usual movie musical trappings to further expose Cabaret’s grotesque and unsentimental overtones amid its inside-outside contrasts. He enlisted sex workers and rotund dancers to play the Kit Kat Club performers and audience roles. He deliberately crafted dances that appeared rough, clumsy, poorly lit, and unwashed. “I tried to make the dances look not as if they were done by me, Bob Fosse, but by some guy who is down and out,” the director said. Still, the music sequences were not a free-for-all; he thought out every unpolished gesture and movement in full consideration of its thematic purpose. Even while drawing inspiration from Dietrich’s iconic appearance in The Blue Angel—Joseph von Sternberg’s 1930 film that ingrained the idea of a Weimar-era club into the cultural consciousness—Fosse resisted the usual razzle-dazzle of his own dance numbers. Applying that degree of glitz would rob Cabaret of its sting, so he resolved to inject razzle-dazzle into the cinematography and editing, earning Oscars for Unsworth and Bretherton. The hyper-contrast, cross-cutting style that Fosse learned on Cabaret would follow him in his next three pictures: Lenny (1974), All That Jazz, and Star 80 (1983).

One of the film’s most pointed visual sequences accompanies the catchiest song, “Money, Money.” Sally and the Emcee perform the number so that it might seem like a critique of the desire for wealth, but it might also be an honest portrait of how money drives them wild. The song occurs during a subplot when Sally meets Baron Maximilian von Heune (Helmut Griem), a laissez-faire German aristocrat and pure capitalist who wants the KPD gone. Max sees the Nazis as a force to carry this out. He has convinced—more likely deluded—himself into thinking the Nazis can be controlled, ignoring that they feed on extremist ideology, not financial gains. Besides an open relationship with his wife that allows him to brush off any moral concerns about sleeping with Sally, and later Brian, Max represents the seductive, debased force of wealth and luxury (“Max really knows how to corrupt a girl,” jokes Sally). While Sally doesn’t hesitate to be seduced by Max—from caviar at dinner to a lavish fur coat—Brian requires coaxing. When Max presents him with a gold cigarette case, Brian replies, “What on earth makes you think I’d accept it?” But even he, too, falls for Max, and not just his wealth. Brian ends up keeping and using the case, and the implication is clear. The three drink, dance, and dine together in a coded thruple. “Money, Money” reminds us how they have been seduced. And the threesome song “Two Ladies,” performed by the Emcee and two singers, one a woman, the other a man in drag, underlines the association.

Amid the wanton desire, Fosse’s potent contrasts in the editing never allow the viewer to forget about the dangers at play. Sally’s vibrant and unsubtle gestures cover up the inescapable future, reminding viewers that her provocative character diverges from or remains oblivious to the national mood. In one of the more timely subplots, Sally becomes pregnant, presumably by Brian. Rather than become a housewife in Cambridge, she obtains an abortion. Roe vs. Wade wouldn’t be established for another year after Cabaret’s release, so the notion, both textually and extra-textually, meant scandal. The film does not condemn Sally for her aversion to motherhood or conventional domesticity. Rather, it condemns her desire to perform alongside her fellow androgynous dancers, contortionists, and grotesque types to an audience of unimpressed Germans whose lack of response to all performances—except the mud wrestlers—implies their lack of interest in entertainment, and therein, their evil. Fosse accentuates this with subliminal editing. When Sally claims to know Emil Jannings, star of The Blue Angel and a Nazi sympathizer, a brief shot of the Emcee whispering “Money” punctuates the moment. Similarly, in the middle of Sally and Brian’s expensive dinner with Max, Fosse cuts to a dead man in the street, having been killed by Nazis.

Through Fosse’s devotion to realism and his persistent editing strategies, which underscore the Nazi threat, he allows his audience to observe the downfall of the Weimar Republic from a critical distance. Watch the chilling scene of Nazi normalization that finds Brian and Max at a public Biergarten, where a Hitler Youth sings “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” and a crowd spontaneously sings along. Some old-timers shake their heads in disapproval, but most sing with salivating enthusiasm, prompting Brian and Max to leave. The scene marks a depression in the film’s mood: No doubt realizing he was wrong that anyone could control the Nazis, Max skips town for Argentina; Sally’s landlord rants about the “established fact” of a Jewish conspiracy; fascists vandalize Natalia’s home and kill her dog; fed up, Brian confronts some Nazis and ends up with a black eye and injured hand. Fosse cuts such scenes around the Emcee performing “If You Could See Her” opposite a dancer in a gorilla suit. The otherwise tender notes of empathy for difference become acidic with the lyric, “If you could see her through my eyes, she wouldn’t look Jewish at all”—followed by a zippy musical wrap-up that serves as a demented punchline, making light of Nazi ideology.

Although Cabaret remains lauded today, some contemporary critics saw Fosse’s work as a betrayal of blithe musicals from Hollywood’s Golden Age. They weren’t ready for Fosse to redefine the boundaries of the genre. Some, such as Pauline Kael or the critic in Variety, recognized Fosse’s work as “most unusual” but also “literate, bawdy, sophisticated, sensual, cynical, heart-warming, and disturbingly thought-provoking.” Audiences agreed, earning the film over $42 million against the nearly $5 million budget (indeed, Fosse went over budget, as expected). The celebration of the film continued at the Academy Awards ceremony in 1973, where most assumed The Godfather would sweep the evening. However, Cabaret took home eight Oscars for Best Director, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor, Best Cinematography, Best Film Editing, Best Art Direction, Best Sound, and Best Original Song Score; The Godfather earned only three, including Best Picture. Given its success, Fosse’s version of Cabaret would become inextricably linked to the subsequent stage productions on Broadway that adopted many of the film’s changes, such as its additional songs and more detailed exploration of sexuality.

Fosse wanted Cabaret to be about something. He delivered a thoughtfully stylized cautionary tale against self-gratification to the point of distraction, showing how corruptive forces will take over while people focus on their petty concerns and creature comforts. To be sure, Germany embraced Hitler’s assurances about economic stability and absorbed his blame of ethnic groups for the country’s problems. They chose to condemn other human beings if it meant a chance to solve their perceived problems. Fosse twists sensuality and avarice into a display of charmingly wretched stage performances, while asking his audience to imagine what they might have done in this situation. What mental gymnastics would you have played, and what heinous acts would you have ignored to remain comfortable? Would you have fled Germany, as so many did? Would you have fought back as part of the resistance? Would you have waited around to see how bad it would get? With its final song, “Cabaret,” performed by Sally in a kind of pathetic victory dampened by personal loss and dread for the future, the film looks at the past and questions whether momentary happiness justifies unfathomable atrocity.

(Note: This essay was commissioned on and posted to Patreon on November 27, 2024. Many thanks to Diana for your continued patronage and selection Cabaret, a personal favorite of mine!)

Bibliography:

Blades, Joe. “The Evolution of ‘Cabaret.’” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 3, 1973, pp. 226–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43795431. Accessed 1 November 2024.

Garebian, Keith. The Making of Cabaret. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Heldt, Guido. “Breaking into Song?: Hollywood Musicals (and After).” Music and Levels of Narration in Film, Intellect, 2013, pp. 135–70. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv9hj7vv.6. Accessed 1 November 2024.

Kael, Pauline. “Grinning.” The New Yorker, February 11, 1972. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1972/02/19/grinning. Accessed 4 November 2024.

Mizejewski, Linda. “Woman, Monsters, and the Masochistic Aesthetic in Fosse’s Cabaret.” Journal of Film and Video, vol. 39, no. 4, 1987, pp. 5–17. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20687790. Accessed 1 November 2024.

—. Divine Decadence: Fascism, Female Spectacle, and the Makings of Sally Bowles. Princeton University Press, 1992.

Morris, Mitchell. “‘Cabaret’, America’s Weimar, and Mythologies of the Gay Subject.” American Music, vol. 22, no. 1, 2004, pp. 145–57. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3592973. Accessed 1 November 2024.

Pearlman, Karen. “Cutting Rhythms in ‘Chicago’ and ‘Cabaret.’” Cinéaste, vol. 34, no. 2, 2009, pp. 28–32. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41690760. Accessed 1 November 2024.

Wasson, Sam. Fosse. Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

Variety Staff. “Cabaret.” Variety, 31 December 1971. https://variety.com/1971/film/reviews/cabaret-2-1200422826/. Accessed 16 November 2024.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review