The Definitives

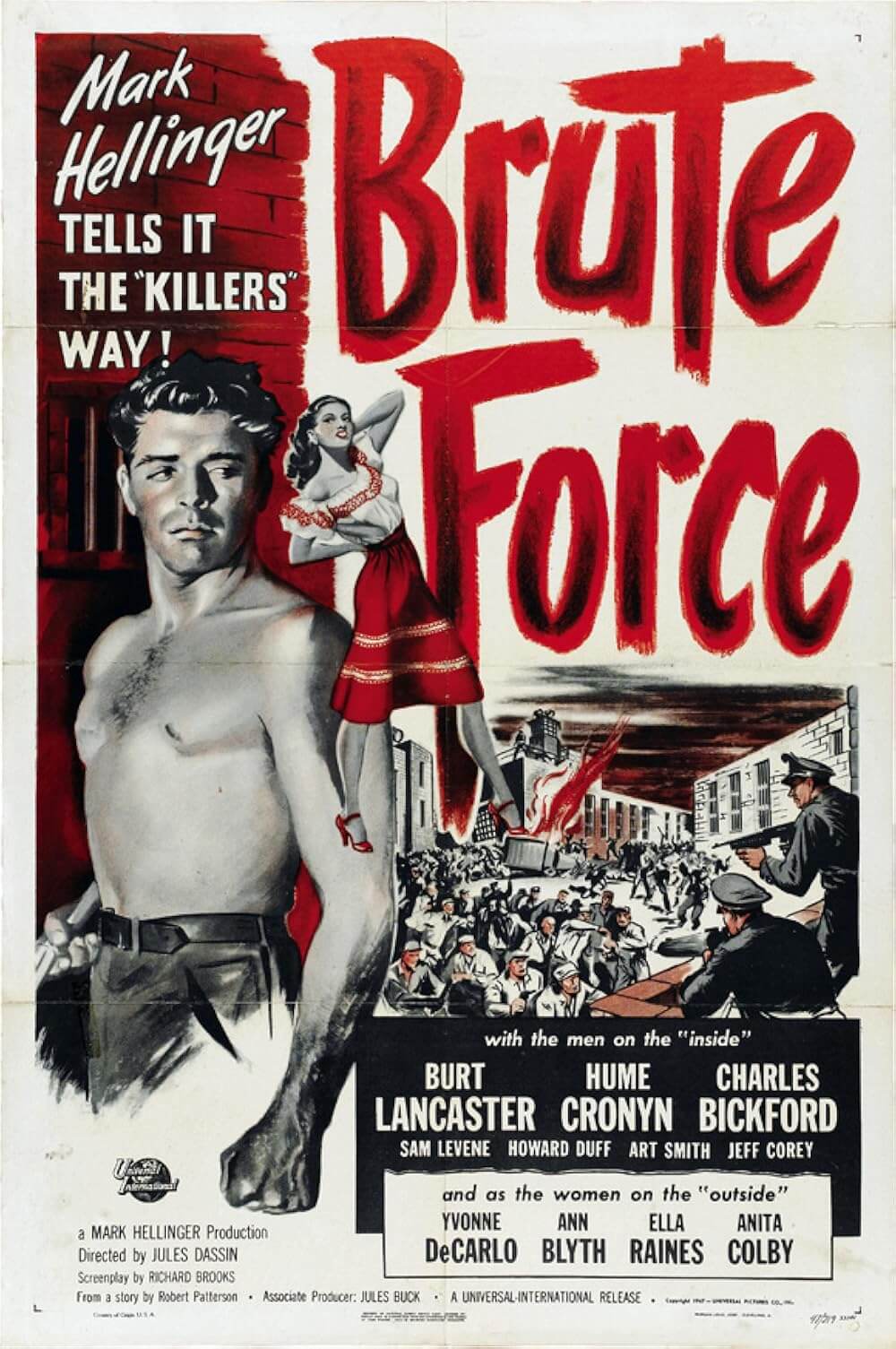

Brute Force (1947)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Editor’s Note: This essay was originally published on April 3, 2007. It has been edited and expanded.

Jules Dassin’s Brute Force tells the story of the inmates in cell R17 at Westgate Prison, whose desperate attempt to preserve their humanity hinges on escape. The prisoners’ eventual bid for freedom relies on a single, fierce attack to overrun the guards and open the main gate. But Dassin portrays the prison, under the fascist command of the resident Captain of the Guard, more like a Nazi POW camp than a penitentiary filled with hardened criminals, lending the picture chilling implications. Dassin, producer Mark Hellinger, and screenwriter Richard Brooks speak to politically subversive ideals for the time, suffusing the finale with a noirish fatalism all but mandated by Hollywood’s moral police at the Production Code offices. Still, in shining a light on the barbaric treatment of those incarcerated by the people who oversee them, Brute Force presents the American prison system as a microcosm of the whole country. From the corporate ladder to the highest political offices, the film questions leaders who demand obedience and exact punishments that go beyond excessive and bleed into the downright cruel and savage—all while sympathizing with an underclass who have no other choice but to fight to be treated as human beings.

Brute Force was released in 1947, between the fight against fascism in World War II and the similar threat of McCarthyist witch hunts. The film dramatizes how, even after the defeat of Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, crypto-fascist authorities threatened American society from within. But the film’s commentary goes even further, examining American culture as a form of captivity that interns the individual within domestic expectations and social pressures. Although it is a prison film, it portrays a dark reality with the visual characteristics of film noir—not only the evocative use of chiaroscuro light and shadow, but also the bleak worldview associated with this breed of postwar crime cinema. Shot on studio soundstages and photographed by William Daniels, who follows Dassin’s penchant for mobile camerawork, Brute Force even plays like a film noir, a mode Dassin later mastered, by combining its stylistic hallmarks with a parallel sense of murky predestinarianism. But it’s also a picture of intense action and melodrama, underscored by Miklós Rózsa’s music. Widely viewed as a mere prison drama with a punch at the time of its release, it plays today as a grim and cynical reflection of the era that produced it.

Brute Force is seldom categorized as the work of an auteur, given Dassin’s status as a director-for-hire at various studios. After getting his start as an assistant director at RKO, Dassin began directing his first features at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the early 1940s. Later, he worked with 20th Century Fox and other studios. Brute Force marked the first of two features he made at Universal Pictures with Hellinger, a former author and nationally syndicated newspaper columnist who started producing movies in the 1930s. Warner Bros. hired Hellinger to ensure their many gangster films looked authentic—among them The Roaring Twenties (1939), They Drive by Night (1940), and High Sierra (1941). After less than a decade in Hollywood, he established his own production unit at Universal, applying his journalistic style to a vibrant strain of crime cinema. There, he produced two pictures directed by Dassin. After Brute Force, they collaborated on The Naked City (1948), which inspired a short-lived television show a decade later. And while Hellinger’s presence behind the camera remains unmistakable in the film’s interest in humanist themes and realistic crime, Dassin’s affinity for noirish stories and antifascist material made them a perfect match as producer and director. Brute Force’s star rounded out the like-minded trio.

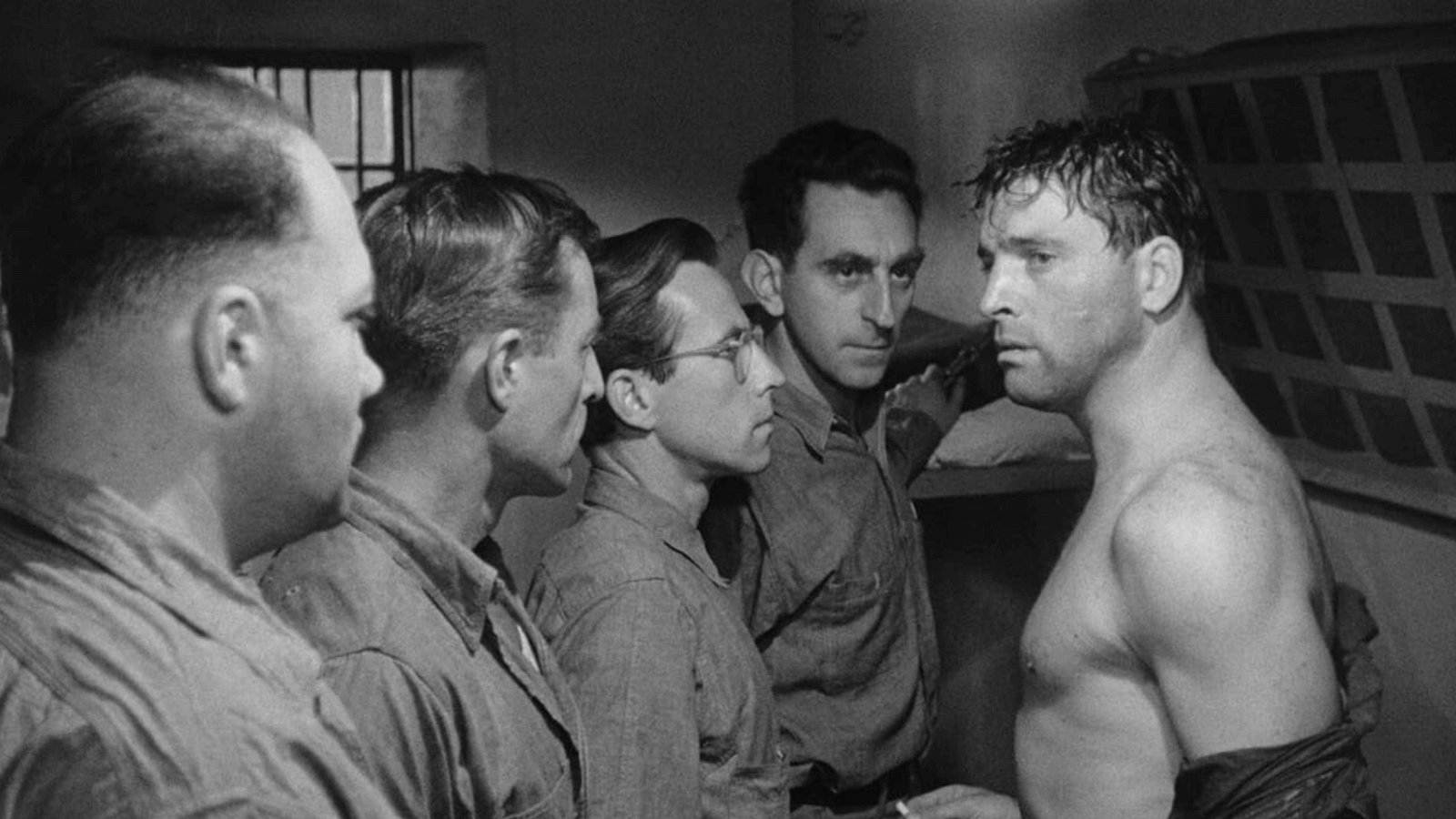

Burt Lancaster plays Joe Collins, a con desperate to escape prison because his lover, Ruth (Ann Blyth), somehow unaware of her beau’s incarceration, refuses a cancer operation until he sits by her side. With that motivation, Collins resorts to quick, aggressive action to get himself out, leading to an unforgettable climax that proclaims the film’s social relevance to the period. It was only Lancaster’s second role, but his genius blazed in his eyes with fiery intensity and the crackle of a pensive furnace burning within. Collins and his fellow cellmates try to break out, and though only two machine guns and an operations tower stand in their way, their attempt cannot end well. No matter the outcome, there’s a moral conflict that the Production Code could not ignore: either the prisoners escape, allowing criminals to go free, or the prisoners remain in jail, in which case Ruth dies, and the inmates remain tormented. Given the era of its release, and the Production Code’s policies that demanded a right and ethical impression must be left on the audience, Brute Force is unresolvably torn between the rule of law and the ingrained humanist conflict.

However, that didn’t prevent Dassin and screenwriter Richard Brooks—who would go on to direct Blackboard Jungle (1955), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), and Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977)—from presenting the legal system, especially prisons, as a callous, unsympathetic, and inhumane societal problem. Such commentary was dangerous rhetoric in postwar America, where the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy sought to identify and investigate citizens, both public and private, whom they deemed disloyal to the American cause. By making anti-establishment films such as Brute Force and capitalist critiques such as Thieves’ Highway (1949), Dassin risked his off-screen reputation. After all, his Russian and Jewish lineage already singled him out among his contemporaries, and his political affiliations—he joined the Communist Party during the Great Depression in his early twenties—would later come back to haunt him. In the 1950s, the director fell victim to McCarthyism and was blacklisted, along with several members of his Brute Force cast: Roman Bohnen, Howland Chamberlain, Jeff Corey, and Art Smith. After making his last Hollywood picture with Night and the City (1951), Dassin left the country for Europe in 1953. His career never reached the same artistic swell he enjoyed in Hollywood, despite making a masterpiece, Rififi (1955), during his exile in France.

For Lancaster, an actor with outspoken liberal tendencies, Brute Force’s message was clear and perfectly suited to his humanist ideals, which he carried into his roles in Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), The Train (1964), and Seven Days in May (also 1964). His first appearance on film was in the 1946 film noir The Killers, another Brooks script, based on Ernest Hemingway’s short story. Hired by Hellinger, Lancaster was not the producer’s first choice to play the role of “the Swede” in The Killers. Van Heflin, Edmund O’Brien, and Wayne Norris were all considered before Lancaster. As the Hollywood legend goes, during a casting call, the imposing actor lugged himself in and spoke the Swede’s lines with pitch-perfect small-town passivity, as if written by Hemingway himself. Hellinger found Lancaster ideal for the role, thinking he was not so much acting as naturally fitting the part. But once the audition was over and Lancaster was hired, the actor returned to his normal, intellectual self. Hellinger, duped into thinking the actor was the character, felt Lancaster had proved his untested skill. The producer was so impressed with Lancaster’s performance in The Killers that he hired him to star in Brute Force, which was released the same year Hellinger suffered a fatal heart attack.

Both The Killers and Brute Force propelled Lancaster into stardom and began a career that established him as one of Hollywood’s greatest screen legends. With roles in American classics such as From Here to Eternity (1953) and Sweet Smell of Success (1957), as well as international and arthouse films such as Il Gattopardo (The Leopard, 1963) and Atlantic City (1981), Lancaster brought integrity and class to every performance, in a prolific filmography spanning both genres and decades. Lancaster’s intense performance as Joe Collins exemplifies the everyman hero struggling against an unfathomable power. Collins is not a violent or depraved criminal; he is just a human being determined to break free of that which holds him back. Be it iron bars, a ruthless dictator like the Captain of the Guard, Munsey (Hume Cronyn), or a gate leading to freedom, he intends to destroy whatever stands in his way and escape. Lancaster gives the role a dignified yet urgent presence, not just because Brooks wrote his dialogue with these qualities, but also because Lancaster emotes without the need for words.

Brute Force presents Collins and the prisoners of cell R17 as anything but career criminals. Though the characters can be violent and cliquey, they never resemble the hardened inmates of HBO’s Oz (1997-2003), Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet (2009), or any number prison movies that depict penitentiaries as incubators of criminal socialization and recidivism. Rather, Brute Force shows the incarcerated population as a group of average men whose crimes may involve theft, murder, and organized crime. But the film also humanizes them so their crimes do not negate their status as human beings. What is more, the men inside follow the strict Us vs. Them code found in most prison movies, where informing The Powers That Be is a violation of an unwritten code. One subplot involves the prison population cornering a snitch, Wilson (James O’Rear), who informed on Collins to Munsey—the equivalent of an American POW selling U.S. secrets to the Nazis for leniency. When the film opens, Collins has just been released from solitary confinement after Wilson’s betrayal. The rat’s comeuppance arrives when Collins’ friends carry out the equivalent of a war crime punishment on the battlefield: they force Wilson into a hydraulic press for corrugated metal sheets, and though shown off-screen, his screams prove unsettling.

The prison community works as a whole. Like soldiers fighting for the same country, they are unified against a single enemy. Without allusions to drugs, rape, or unforgivable crimes, Brute Force presents a prison of agreeable men. Dassin does not ask us to pardon or look beyond their crimes; rather, he acknowledges that, no matter what they did, the inmates deserve better than the treatment they receive from Munsey. During several melodrama-infused flashbacks, each inmate from R17 shares his backstory while reflecting on a pinup girl posted on the cell wall—a painting by John Decker, purportedly an amalgam of Ann Blyth, Yvonne De Carlo, and Ella Raines. Her facial features are undefined, her eyes are closed, and her expression is neutral, providing a blank canvas on which each inmate can project his sweetheart. The picture reminds the men of how they took the rap for a woman, were betrayed by a woman, or desperately want to escape for a woman. In each case, the prisoners reveal themselves to be more than an embodiment of their crimes. Granted, most prison films allow the audience to identify with their inmates, and with Brute Force, too, we genuinely feel for these men. The flashbacks yearn for understanding and combat the stigmas about incarcerated men, whose humanity is regularly tested and questioned by the institutions that imprison them.

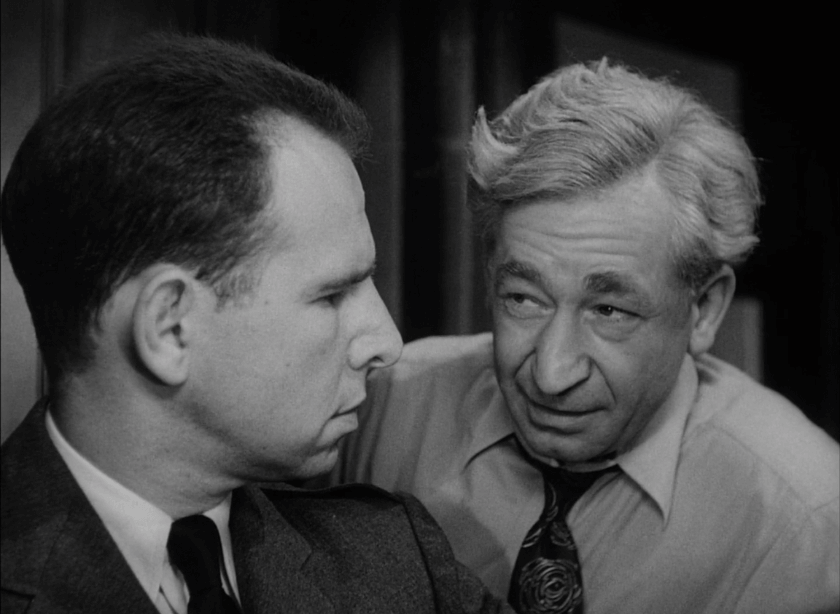

However, the meek, ineffectual Warden Barnes (Roman Bohnen) appears more worried about his career than the conditions in his dangerously overpopulated prison. “Everything’s gone wrong,” says the warden. “I don’t know who’s to blame, but I do know that every prisoner hates us.” The warden remains unaware that Munsey has been using a common fascist tactic: his cruelty fuels the population’s aggression, inciting them to overreact during a conflict, which he then uses as a pretense to justify coming down even harder on them to assert control. Only the prison’s Dr. Walters (Art Smith), who numbs his aching morals with heavy doses of brandy, recognizes Munsey’s deceitful strategy: “All you want is to destroy instead of build. What we need here is a little more patience, and much more understanding,” Dr. Walters declares. He accuses Munsey of behaving worse than the inmates and argues in favor of rehabilitation, even though he knows the overpopulated prison cannot manage it: “All I know is that when people are sick, you don’t cure them by making them sicker. By your methods, we send a man back to society a worse criminal than he was when they sent him to us.” Nevertheless, the warden wants Munsey to implement “absolute discipline,” which only heightens the tensions.

For postwar Americans watching Brute Force upon its original release, Collins and his fellow prisoners seemed more like captives in a POW camp. To be sure, the story aligns more with The Great Escape (1963) than Escape from Alcatraz (1979). Unjustly treated by the authoritarian Capt. Munsey, the film presents escape as Collins’ duty, just as it would be a soldier’s imperative to escape from the enemy during wartime. The plot could very well be formatted to tell a POW drama. However, the setup also reinforces many of the ideas in Michel Foucault’s landmark 1975 study, Discipline and Punish. Foucault’s investigation of modern prison mechanisms and methods outlines the problems with each. Disciplining through captivity—the goal of the prison system—does little to rehabilitate the criminal. The prison, as it is now commonly thought, melds all forms of criminality into a single blade, and when prisoners are released, that blade comes striking down on society. In rare cases, social programs such as Rehabilitation Through the Arts help incarcerated persons develop the emotional intelligence and self-awareness that prevent them from landing in prison again. And yet, given Brute Force’s portrayal of its inmates, we cannot imagine a single prisoner in the film becoming a part of that blade, unless Munsey drives them to it.

Given that Brute Force is a studio film from a period of conformity in Hollywood, it bears certain narrative clichés, such as flashbacks to the inmates’ lives. In contrast to the rest of the film, these flashbacks underscore what’s unconventional about Brute Force: the characters feel more like everyday Americans than criminals. This reframes the prison as a metaphor for America’s fascistic social tendencies and comparable internment in 9-to-5 careers, the social ideal of the nuclear family, and the impossible-to-achieve American Dream. Returning from World War II in 1945, American soldiers removed their military uniforms and put on ties and name tags associated with their new office jobs. The gray flannel suit worn by the Average Joe (formerly G.I. Joe) closed him off from the world much like a prison jumpsuit. For these men, stuck in positions they often had no interest in, their careers and even families became another kind of penitentiary. Complacency and the death of imagination were embraced as employment norms. The only way out, for a fraction of them, was feeling useful in the Korean War. The majority, however, were confined behind stacks of paperwork mounting on their desks. For them, Brute Force speaks against contentment in such a humdrum existence and urges them to fight back for a more rewarding life.

Brute Force’s villain, Capt. Munsey, a Nietzschean Übermensch in a position of considerable power, maintains a dictator’s megalomania meant to draw associations with Hitler. It remains ironic that a position of such authority would be held by someone so unsubstantiated in a physical sense, fueling Munsey’s Napoleon complex. Cronyn does not impress at 5’6”, particularly when standing next to Lancaster, who towered over Cronyn at 6’2”. But when Munsey enters the mess hall, the room of prisoners goes silent out of fear. Consider also the scene in Munsey’s office, where he beats a prisoner with a pipe; meanwhile, just outside the door, the other guards eat lunch, twisting and turning in moral discomfort over what they hear. But like the warden, they remain too afraid to question Munsey. Only Dr. Walters confronts Munsey’s methods: “Not cleverness. Not imagination. Just force—brute force that makes leaders and destroys them.” The film’s allusions to Hitler remain unmissable and intentional, whereas from today’s perspective, other authoritarian leaders and tactics come to mind.

Even without the extratextual associations, Munsey is among the most despicable villains in film history. He delights in tormenting the men under his control, as suggested by a sketch of Michelangelo’s sculpture The Rebellious Slave in his office, portraying a figure with his arms bound behind him. Nearby is a regal-looking photo of Munsey in uniform. The juxtaposition of the two images suggests he keeps the prisoners in bondage, and he takes pride in his masochistic control over them. Munsey also delights in tormenting the six men crammed into R17. Explaining that he gets “quite a kick out of censoring the mail,” Munsey lies and tells Tom (Whit Bissell) that his wife has written and asked for a divorce. This cruel fabrication is so devastating that Tom commits suicide in the cell. And it’s no coincidence that Munsey kills Louie, played by Sam Levene, a Jewish actor, while beating him for information about the planned escape attempt. The torturous beating is an act of pure sadism, as Munsey already knows the time and location of the escape. Moreover, the scene features Munsey playing a record of the Tannhäuser Overture, by Hitler’s favorite composer, Richard Wagner. Going even further to demonize Munsey, the film makes biblical allusions when he washes his hands like Pontius Pilate and calls weakness “an infection that makes a man a follower instead of a leader.” This contrasts Dr. Walter’s evocation of Jesus, when he suggests Munsey’s treatment goes against Christ’s empathy for the meek: “Seems to me a very great leader once said the meek shall inherit the Earth.”

When watching Brute Force, one cannot help but think of Franz Kafka’s short story “In the Penal Colony” (1919). Kafka’s story involves a prison island where the interned receive punishments in the form of a rickety table that inscribes their crimes onto their bodies in increasingly deeper cuts, until the prisoner dies, having supposedly achieved a spiritual clarity. Inevitably, the chair collapses overuse and disrepair, suggesting that a reliance on torturous punishment will lead to the prison apparatus failing. Similarly, Munsey punishes the prisoners of cell R17 with such a sick, dogmatic logic that the machine breaks down. Unwilling to tolerate Munsey and his fascist grip on their lives, the prisoners rise up and attempt to escape. Kafka’s story ends much like Brute Force, with the instrument of punishment (Munsey) falling apart; the machine that inscribes the law (Munsey and his prison) onto the criminal’s body (the prisoners) goes to pieces, evoking a dysfunctional, often unjust penal system. Once the prisoners land the first Molotov cocktail onto the machine gun tower in the final riot scenes of Brute Force, one imagines the machine from Kafka’s story coming loose and crumbling into an unrecognizable confusion of parts.

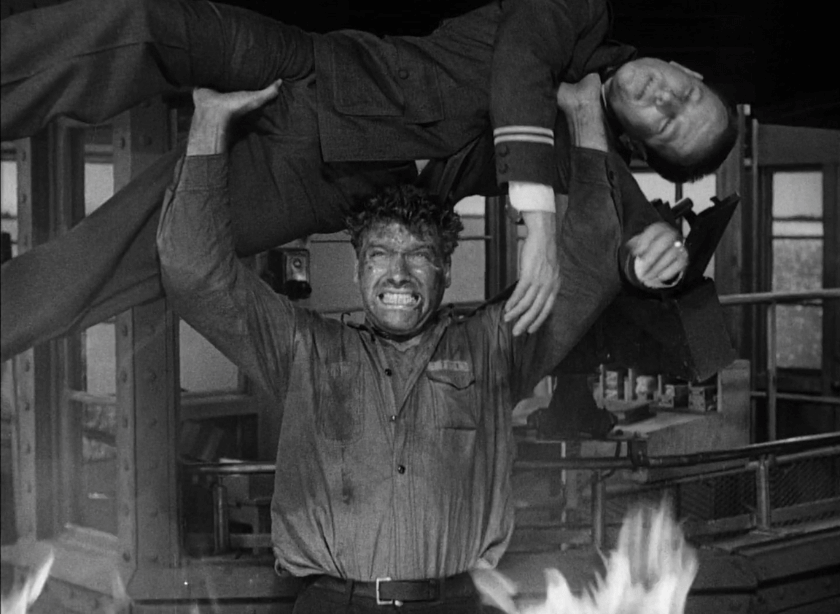

This may lead one to believe that the people (prisoners) have the power, and leadership (Munsey and those who follow him), who are few, have none. Except the fatalistic worldview of film noir says otherwise. While Collins and his cohorts have only to take out two machine guns and open the front gate, their plan fails. Munsey is announced as the replacement for Warden Barnes, and his guards shoot down most of Collins’ crew. After taking a bullet himself, Collins mounts the watchtower stairs to confront Munsey. Below, the crowd of prisoners panics amid the gunfire and flames. One man attempts to drive a truck to freedom and inadvertently blocks the front gate from opening. If there’s any victory, it’s that Collins delivers a cathartic retribution. He raises Munsey above his head and tosses his body from the tower to his death. Even though the prisoners’ escape plan misfires, their victory over Munsey is enough to stop his cruelty against those who survived. It is a temporary victory. Though some stand up to authoritarian individuals and institutions, many others elect them or stand by, as if helpless to stop their tyranny and abuses of power. In either case, people are trapped—by their elected representatives, employers, and anyone who has power over them. Dassin slaps his audience with his film’s deliberate last line that confronts society’s literal and existential prisons: “Nobody escapes. Nobody ever really escapes.”

Dassin had wanted to make a prison film for years, but he was unsatisfied with the result. Hellinger insisted on the subplots about women in the story, and Dassin felt this neutralized his prisoner characters. After calling it a “dumb picture,” Dassin told Patrick McGilligan and Paul Buhle that “all these prisoners are such nice sweet guys […] what are they doing in jail!” Regardless of Dassin’s complaints, the prisoners in R17 are no angels, and Hellinger had to fight with the Production Code office to convince them of the necessity for extreme violence and heroes of dubious morals in the film. Moreover, critics praised the film. The New York Times remarked on Dassin’s “steel-springed direction,” and Variety admired its “showmanly mixture” of genres. Of course, from a contemporary perspective, the film ignores that over 30% of incarcerated US men in the 1940s were Black, and aside from the occasional Calypso singing by Sir Lancelot, it features no actors of color. The disparity would be even more pronounced (and conspicuously imbalanced) today, given that, according to a 2025 report by the US Sentencing Commission, Black communities represent only about 14% of the US population yet make up a disproportionately high 35% of all incarcerated persons. And the film has only become more potent as America’s prison industrial system has turned into a form of slavery, monetizing dehumanization on a mass scale.

Brute Force is an uncommonly tough movie for 1947, and for today. While it’s a superb prison-escape picture, its lasting impact remains the never-ending battle of the oppressed against imbalanced systems of power. American soldiers came back from fighting fascists after World War II only to find a similar type of repression waiting for them at home, in the workplace, and in American politics: their own personal POW camp. What’s worse, their defeat of fascism proved impermanent, as it has returned to America in unprecedented ways. Brute Force implies that systems of hierarchical power—through social pressure, economics, corporate structures, class, or caste—will persist unless people learn to fight them. If people resolve not to fight, they will remain prisoners. Brute Force confronts the fact that the battle is about more than stopping the power-hungry individuals (the Hitlers, the Munseys); it’s about combating a system that allows the cruel into positions of power, where they exploit and stomp on the meek. The struggle is ongoing, and though it may end in defeat for those who fight injustice and cruelty, it is not without a greater symbolic meaning.

Bibliography:

Bishop, Jim. The Mark Hellinger Story: A Biography of Broadway and Hollywood. Papamoa Press, 2018.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon Books, 1977.

McGilligan, Patrick, and Paul Buhle. Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist. University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Neve, Brian et al., editors. “Un-American” Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era. Rutgers University Press, 2007.

Shelley, Peter. Jules Dassin: The Life and Films. McFarland, 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review