The Definitives

Brazil (1985)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The world of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil has been subjugated by a paperwork-obsessed authority. Stamps, forms, and proper clearances wear down on and render freedoms meaningless, the layers of inescapable officialdoms draining all humanity. Inundated by the prevailing bureaucracy dominating nearly every aspect of human life, the film’s protagonist escapes through the only means available to him: his dreams, wherein he imagines himself a fanciful winged knight, determined to rescue his idealized damsel in distress. He tries to transfer the escapist gallantry from his dreamworld to his everyday life and finds reality’s obstacles unmaneuverable; they are piled upon one another so high that they are impossible to overcome. The picture’s ultimate resignation that even in our dreams, escape from The System remains unattainable, materialized into a curious irony when a Hollywood producer nearly prevented Gilliam’s masterpiece, in its complete, cynical form, from being released. But after a long and dirty battle, Brazil triumphed and released a timeless, controversial, and visionary piece of cinema into the modern age. Gilliam’s dream prevailed; however, if he had been fighting in the film’s world, it might not have.

Released in 1985, Brazil marks Gilliam’s fourth complete effort as a filmmaker and his most artistically accomplished motion picture. Characteristic of the director here are details that invade every frame and an unmistakable, inexpressible mythic quality that elevates the picture to something more than cinema. It is a world foreign and unfamiliar, and moreover, it’s so completely the director’s dreams and nightmares come to potent life. With its infiltrating ducts and cloudy dream sequences, Brazil looks and feels unlike any other film, unless it is a Terry Gilliam film. In its technical and design innovations, the film realizes the visual potency of a fever dream through tactile effects and endless creative facets, all filtered through Gilliam’s artistic lenss—where imagination and ambition combine into a force capable of great art and self-destruction in the same motion. This would be the first of many projects for Gilliam where his production mirrored the film he sought to make, bringing into question the director’s unconscious desire to perpetuate a situation where his film must survive its battle to the screen before it can truly reach audiences. No other Gilliam film would reflect its making or this pattern in Gilliam’s career more than Brazil, and through its arrival, realize his incredible vision in a victory over oppressive executives.

Motion pictures such as Brazil that challenge authority thrive in themes of revolution; they succeed both as cult and commercial successes because people inherently desire rebellion, though they generally resist being rebellious themselves. Standing up to your boss or a government may seem unlikely, but watching a film fictionalizing such events is necessary and therapeutic. Films with successful rebellions or anti-authority sentiments—such as Lindsay Anderson’s if…. (1968), David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999), or V for Vendetta (2005)—ultimately maintain despairing undertones when applied to real-life issues. Despairing because, though people cheer on such fantastical films for showing victories over The System, in reality, the bureaucracies usually prevail, hence the fantastical elements in each example. Catharsis of this sort liberates by acknowledging that The System exists and fighting against it through often unrealistic means. It’s part of what makes such films so appealing in their defiance and escapism. But these films forget The System consists of more than one institution; in actuality, our world has constructed systems on top of systems, and those are placed atop other systems, and so on, forever and beyond comprehension.

Brazil refuses to play into the hands of catharsis and is comparable to George Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty Four, the ultimate authoritarian government dystopia novel from 1949. Though for different reasons, both stories end dismally and acknowledge the institution’s eventual victory over the individual. The book served as a warning against a government potentially relying on totalitarianism, which seemed likely to occur, according to Orwell’s book, only a few decades in the future. Brazil goes further and suggests that even the imagination comes under the rule of a dictatorial society. Orwell’s world may be a futurology, or cautionary tale, but the same cannot be said for Brazil. Opening titles describe the setting of Gilliam’s film as existing “Somewhere in the 20th Century.” The city remains unknown, though one could presuppose it takes place in England (it was filmed in England, and Gilliam’s work with the British Monty Python troupe highlights this notion). But rather than assuming a location, consider the setting an allegory representative of all cities and governments here and now: A city with skyscrapers endlessly high, offices with paperwork mandating every action, and wiry contraptions guiding and recording behavior. As a result, imagination, fantasy, and escape are minimally required from humanity.

The inspiration for Gilliam’s science-fiction-infused world originated from a seventeenth-century document found by Gilliam in his research of the Spanish Inquisition. The document detailed the costs of what a person was required to pay for their own witch hunt interrogation. The Inquisition brought observers and character witnesses by the dozen to make or break a witch trial, spending much in official monies in the process; in addition, it took several working hours to torture a potential witness, which also accumulated costs, leaving only the accused to pay for his or her own interrogation or punishment. Gilliam saw a type of maddening bureaucratic logic at work in this document. It was analogous to days filled with endless piles of soul-depleting paperwork, the quantification of all things through high finance and accounting, and inhumane business and social diplomacy spreading like a disease.

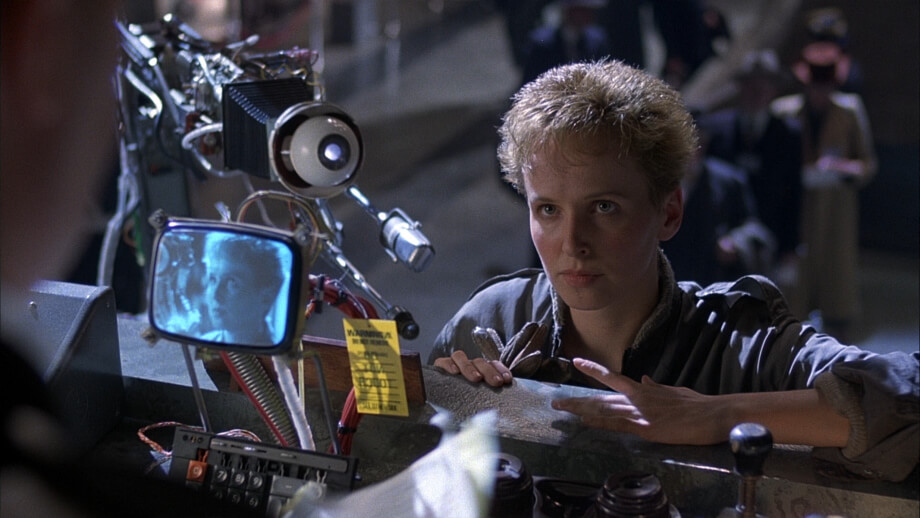

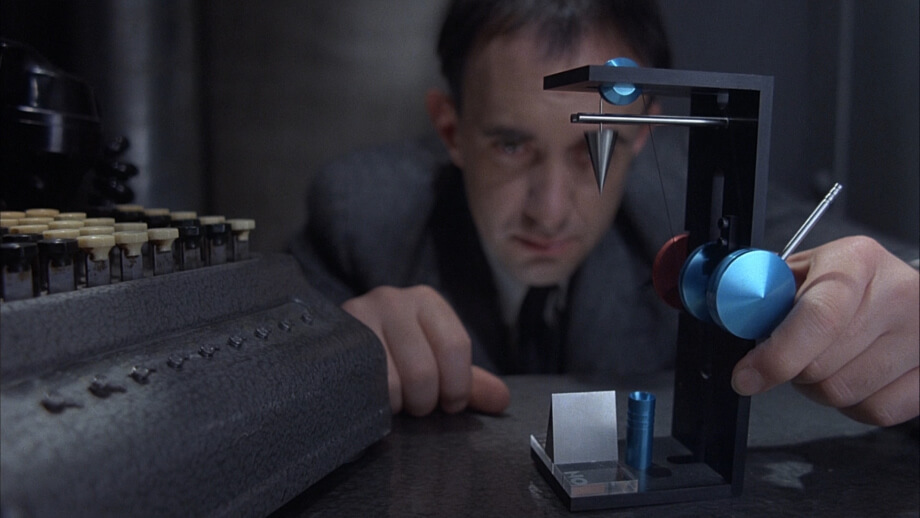

Gilliam insists his picture is not science fiction. The setting nonetheless writhes with industrialized technology as rampant as overgrown vines. Some link science fiction to the future, whereas an alternate reality, someplace unfamiliar, or in this case, an allegory, can exist in a place with fictional technologies in the present day. Visually similar to the subterranean future shown in Gilliam’s own 12 Monkeys (1995), Brazil features apparatuses made up of computer parts and monitors so small they require magnifiers, endless streams of ducts, and absolutist political entities running everything—all familiar, yet exaggerated for the sake of Gilliam’s message. The result is a contemporary-set fictional landscape. Unlike Orwell’s novel, the future totalitarian government is not the enemy—not completely—but rather how modern society floats on a surface of banality and apathy. They compartmentalize how their lives are ruled by bureaucracy, ignore the threat of so-called terrorists, and maintain a tunnel vision to get through their day.

Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce), trapped by this paperwork-obsessed routine at the Ministry of Information’s Department of Records, daydreams. Otherwise unfulfilled by his work for an inept boss, who’s oblivious beyond the deafening sound of the typing pool clicking away, Sam is left to his fantasies. He escapes into his imagination, where he plays a hero—a silver-winged knight fighting desperately against a combative world to save the woman (Kim Greist), literally, of his dreams. One day, Sam sees the face of his fantasy woman somehow tangibly real and knows he must pursue her. The Ministry’s limitless confusion of red tape, with all its forms, receipts, filing, and governmental bric-a-brac, prevents Sam from discovering the identity of his desire made flesh. To find her, he resorts to desperate measures: Sam takes a promotion he does not want into Information Retrieval, which increases his Ministry security clearance and allows him access to confidential information. Once promoted, he begins to be seen by his superiors when normally he would revel in his anonymity; he forgets about the dangers of The System. The actualization of his dream represents the possibility—and the possibility alone—of escape from a collective that is nonetheless inescapable.

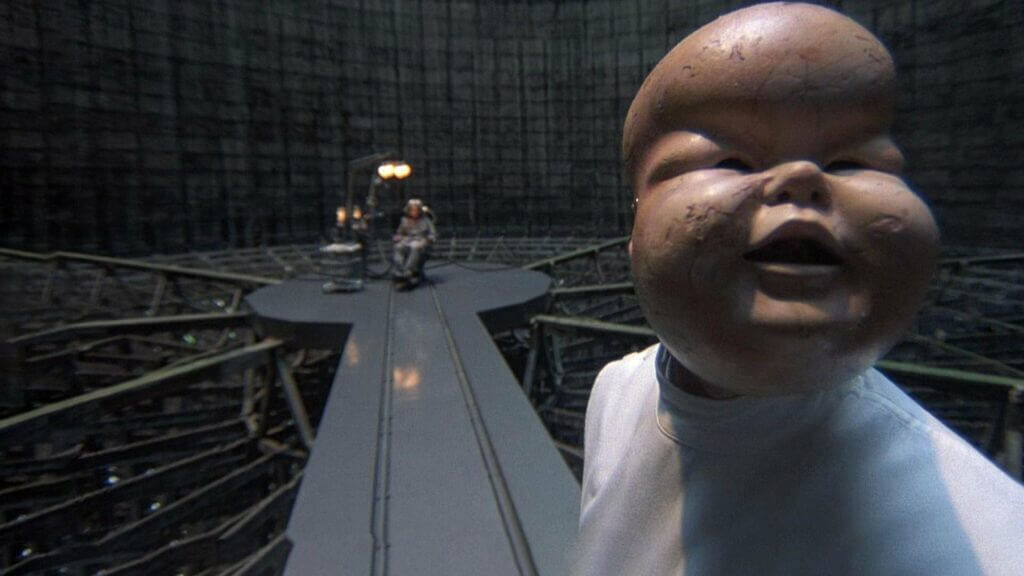

Norman Garwood and Maggie Gray earned an Oscar nomination for their art and set decoration, owing a major portion of their visualizations to Gilliam, whose ceaselessly frenetic imagination exceeds that of any other filmmaker working today. Brazil illustrates a world obstructed by technology and architecture; one rarely, if ever, sees the sky or any form of plant life, bodies of water, or animals—this is an unnatural world. Orderly, yet grimy and dark with the leftovers of smokestacks and long-since-new, ever-malfunctioning mechanisms lingering like dead branches, the physical world intrudes on both the viewer and the film’s characters. By the end of the picture, the viewer feels like a claustrophobic in a shrinking room. Described by Gilliam as “Frank Capra meets Franz Kafka,” the film’s look contains a 1940s architectural and costumed visage combined with a futuristic application of industrialism, expressionism, and Victorianism, along with ubiquitous pipes, neon, and wires strewn about in a mad order. Ducts violate interior sets: large tubes run inelegantly through walls, penetrating internal landscapes, therein symbolizing how even in your home, the inescapable bureaucratic world infiltrates and observes. To film this untidy environment without losing touch with its characters requires a true visionary. Gilliam creates with manic artistry, sensitive both to visual and emotional realms, so much so that he has earned himself a reputation for being preoccupied with auteurisitic details.

Gilliam originally wanted to call his film 1984 ½, combining Orwell’s prophecy with the directorial auteurism of Federico Fellini’s 8½ (1963). A marriage of auteurist drives and idealist machismo, Fellini’s film concerns a director (Italian actor Marcello Mastroianni) embracing dreams in place of a reality that does not suit him. Autobiographical for Fellini, the film entails personal pressures that mushroom while trying to complete his next project (in the film, a science fiction epic). Those stressors distort and enhance his interpretation of the events around him. The viewer of 8½ is never completely sure which scenes represent reality and which represent fantasy. While the title 1984 ½ would have alluded to comparable great works of literature and film, Gilliam’s title has its own metaphor. Gilliam thought up his vacation spot titled Brazil while watching the sunset in the steel-producing city of Port Talbot in Whales. He imagined someone sitting on the blackened, coal dust-ridden beach, listening to a diverting old vacationer’s song like the famous “Maria Elena.” (In some retellings of the title’s story, “Maria Elena” is replaced with the song “Brazil.” In most retellings, Gilliam decides “Maria Elena” should be replaced by “Brazil,” it being a catchier tune. At some point during the film’s production, the Geoff Muldaur version of “Brazil” was chosen for the film’s theme and eventually became the title.) Whether dreaming of escape to Port Talbot or simply hoping for an otherwise impossible escape from Port Talbot, the ironically juxtaposed tune points out the desire to get away. When the song is hummed or echoes on the film’s soundtrack, its sardonic placement underscores the characters’ hopelessness in ever reaching an exotic beach, sunshine, or escape.

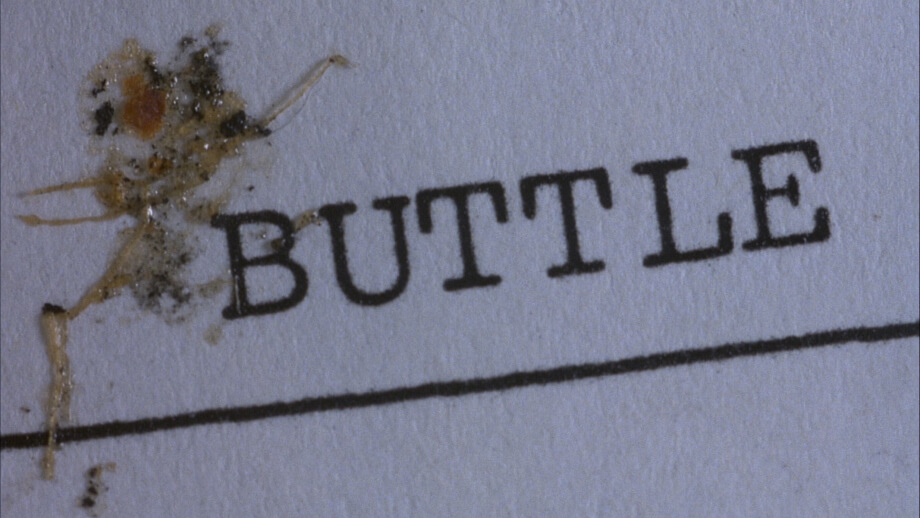

But there is no escape in Gilliam’s film, and he and co-writer Charles McKeown’s outlook offers no technological safeguards or contingencies to protect their characters—just brutal, unthinking bureaucracy. Consider how the film introduces its leads to each other. Sam and the real-life version of his fantasy, Jill Layton, meet through the brilliant device of a clerical error. One of the film’s first scenes shows a nameless Ministry technician in his office. A printer cranks out a never-ending stream of documents. A fly buzzes about the room. The stuffy employee waves at it with a newspaper, and the fly lands on the ceiling. On an assortment of office furniture, the clerk climbs up to the fly and swats the insect. The squashed thing falls. Below, names flash by on the printer, all with the name “Tuttle.” When the fly lands in the printer, one of the files soiled with insect goo suddenly reads “Buttle.” As a result of a swatted fly, a chain of events occurs, which leads to the wrongful capture and execution of a citizen named Buttle. Jill, a strong antiauthoritarian whose neighbor is the widow Buttle, sets off to report the Ministry’s error and finds herself confronted with absurd forms and unmoved government employees. Inevitably, due to this mishap, Sam sees Jill, a woman whose face he has seen a thousand times in the playground of his mind. Elsewhere, wanted “terrorist” Harry Tuttle (Robert De Niro), a subversive heating engineer who refuses to work within the reigning Central Services, survives thanks to the fly.

Independent for the intrigue of freelance servicing, adventure keeps Tuttle on the move. Both Central Services and The Ministry view him as a terrorist because he lives his dream. Sam meets the rogue character after ringing Central Services to fix the haywire heating in his apartment. Tuttle intercepts the call and undercuts the licensed servicemen (Bob Hoskins and Derrick O’Connor). Immediately, Sam sees Tuttle as a hero for the same reason The Powers That Be view him as a threat: he is free. And though Sam traditionally does everything he can to avoid being suspected or even noticed, he begins to choose abnormal associations: Harry Tuttle and Jill, the latter a strong woman and defiant trucker, are both suspected terrorists for their refusal to obey the Central Services regime. Neither Sam nor Tuttle nor Jill are “terrorists” in a political sense. They are the only dreamers in the film. The Ministry of Information’s propaganda claims Tuttle and those like him (citizens refusing complacency and adherence) engage in terrorism, random bombings, and so forth. Explosions in public places occur, and people learn to ignore them as normal because they trust their government; yet, we never see the agitator behind these “attacks.” Are there really terrorists, or does the government cause these explosions to create a sense of chaos and fear to encourage obedience? Given a choice between anarchy and order, most will take order.

The Ministry’s propaganda machine cranks steadily. Posters broadcast fear-inducing indoctrinations against independent thought, such as “Suspicion Breeds Confidence,” “Loose Talk Is Noose Talk,” “The Truth Shall Make You Free,” and “Don’t Suspect a Friend, Report Him.” The endless paperwork records peoples’ activities. Scanning devices are everywhere. People are designated by their security level. Big Brothers’ eyes never waver from their fixed position on each and every member of this society. Comically, Big Brother’s dependence on technology sometimes backfires, as with the printers thwarted by a swatted fly. At the Department of Records, Sam’s boss, Mr. Kurtzmann (Ian Holm), stands watch over an ocean of workstations. After Kurtzmann disappears into his office, he hears the echoing sound of hundreds of employees clicking over from their workscreens to a raucous cowboy movie. Kurtzmann rushes back to the door and opens it, hoping to catch everyone in the act, but not before the employees can switch back to their workscreens. With suspicion, he shuts the door, and the Western snaps back on. Kurtzmann, as a boss, is ineffectual. He is unsure of himself, though his confidence in the authority of his position is concrete, so when something complicated comes up, Kurtzmann leaves the details to Sam. When the Ministry realizes their error in processing Buttle, Kurtzmann sends Sam to deliver Buttle’s widow a refund check for the arrest and execution costs.

In depicting a world obsessed with formalities, scrutiny, and micro-management, Gilliam could not help but obsess over the details, a trait for which he is infamous. Brazil’s lush production contains layers upon layers of texts, both visual and thematic. The aforementioned propaganda never occupies the full frame; posters resembling World War II and Cold War slogans appear only in the background and are often out of focus. Many of Brazil’s most fascinating details inhabit the backdrop or reside in the subtle humor and satire from scene to scene. In the interpretational sense, this film requires reading from the viewer, and to see every little activity of every character in every scene requires multiple viewings. Gilliam’s career is filled with pictures harboring details beyond the scope of a normal film. Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe, two documentary filmmakers, have followed Gilliam’s career closely, making two feature-length behind-the-scenes documentaries about Terry Gilliam productions. Their first was entitled The Hamster Factor and Other Tales of 12 Monkeys and detailed the making of Gillaim’s biggest moneymaker. Pepe and Fulton show the director’s detail-fixated genius, “The Hamster Factor” from their title, referring to a point in 12 Monkeys’ production when Gilliam became more concerned with the behavior of a hamster out of focus in the foreground than with the film’s star, Bruce Willis, in the background. Hours were spent in an attempt to convince a hamster to run in a wheel as Gilliam wanted. Meanwhile, an entire production crew stood idling, waiting for Gilliam to be pleased with a meager detail (which Gilliam admits that no one but him will probably notice). Driven by the smallest specificity, Gilliam never stops chasing his vision.

The character Sam, on the other hand, overlooks the most minuscule details and it leads to his end. To find Jill, his actions, while within the context of the film seem unthreatening and almost passive (for example, taking a promotion to indirectly subvert The System), are dangerous in a roundabout way. Sam does not deliberately undermine authority until he grows frustrated with his inefficient world; his intentions are only to quietly seek out his dreams—to get the hamster to run in the wheel. Yet, because of their nature, dreams of Sam’s sort are criminal; only the dreams of an ambitious young executive seem rational in this world. During an obligatory dinner with his plastic-surgery-addicted mother (Katherine Helmond), a character who progressively gets younger and younger looking as the film goes on after multiple procedures with her doctor (Jim Broadbent), Sam is pressured to take the promotion to Information Retrieval. He resists, and she asks him, “You must have hopes, wishes, dreams!?” But for Sam to disclose his escape fantasies would be a dangerous admission—to deny this bureaucratic world and acknowledge his resistance against it would mean he somehow has refused to accept his position, refused to conform. Though it subsists only as a symptom of his desire, dreaming is inherently rebellious in Brazil’s world. After all, the government has, in effect, made nonconformity, thus dreaming, an act of terrorism.

At the same time, the woman of Sam’s dreams is so close he can almost touch her. After accepting the promotion to find her, he sees Jill by chance in the Ministry lobby about to be arrested for still inquiring into their Buttle blunder. He uses his new clearances to help her avoid arrest. Later, he cannot help but admit his dreams and love for her, sounding less like a stalker than open-hearted. Little by little, as his dream comes true and Sam falls in love with the real Jill, he grows more intolerant of his inefficient and ineffectual world and begins to resist. He ignores official procedures and disregards his duties, soon tallied by The System and interpreted as a pattern of rebellion. In his sole antiauthority act to keep The Ministry away, Sam falsifies a record of Jill’s death. He undermines The Ministry by helping her escape, and he returns to Jill, who now returns his love, to celebrate (“Care for a little necrophilia?” she asks, joking about her official status as deceased). Gilliam gives his audience only a brief moment of happiness between Sam and Jill before foot soldiers crash in through the windows, killing off Sam’s hopes. Sam’s clerical mistakes and manipulations to find and protect Jill have now caught up with him. The woman of his dreams is executed while resisting arrest. The Ministry prevails and processes Sam, preparing him for a torturous interrogation.

Sam drifts away. In his catatonic reverie, he imagines Harry Tuttle and a band of freedom fighters bursting on the scene to carry out a daring rescue. Joining with this figure of heroism in the face of oppression, Sam and Tuttle together demolish The Ministry’s headquarters and bring down the establishment. They narrowly escape capture when Tuttle is blanketed by a swarm of loose papers, which coat and consume him, only to blow away into nothingness, signifying the helpless and absolute officialdom of Brazil’s world. As Sam’s escapist victory continues, he finds Jill. They evade capture to a paradise far away from skyscrapers, advertisements, propaganda, and ducts—a place where the blue skies and green pastures of Sam’s heroic daydreaming come to life. Except no such haven exists; all dreams and fantasies are false in Gilliam’s film. Sam’s hopes of happiness and escape from The System were as surreally improbable as getting away to a nice vacation spot on Port Talbot’s coal dust-blanketed beach. In reality, Sam’s shock over Jill’s death has forced his mental collapse. The film’s ending punctuates how The System of the world dominates all, regardless of how independent one may feel. Gilliam recognizes the only way to escape is to dream. How else can we be satisfied with life?

Unlike Sam, Terry Gilliam’s struggle to create his dream, in this case Brazil, succeeded, though not without a battle. The heavily publicized war over his film’s release earned Gilliam the reputation of a troublemaker among Hollywood studio executives in the subsequent years, some of whom claim that Gilliam thrives on anarchy. Their point is not without some merit. Gilliam shares peculiar similarities to his main character. Both he and Sam are their own worst enemies from an official standpoint. In one dream sequence during the film’s first half, the winged superhero version of Sam fights against the personification of The Ministry: a massive, faceless samurai warrior decorated in metallic armor. The samurai disappears and reappears at random. Sam gets the upper hand and wounds the warrior; it bleeds bright orange and blue flame, and then topples over onto its back. Sam creeps up slowly on the samurai’s body and removes its face plate; when he does, he sees his own face on the warrior. In the real world of Brazil, this dream foreshadows how Sam’s growing, reckless paper trail catches up with him in the end. He tries so desperately to find Jill that he forgets he is always being watched. He becomes hasty in his desire for freedom; it leads to Jill’s death and his own descent into madness. Gilliam’s analogous reputation as a filmmaker has been marked with problem productions. His critics suggest the issue resides in his unwillingness to compromise his art, surrender his often dramatic battles with studios, and a mystical-yet-unintentional attraction to chaos. Brazil’s famous production history best signifies the director’s curse-like magnetism to ill-fated productions and his likeness to Sam’s paper trail.

For years, the idea of Brazil circled in Gilliam’s head. After writing the script with McKeown, the director’s previous commercial successes with Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), Time Bandits (1981), and Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life intro The Crimson Permanent Assurance (1983) promised the director would be seen by studios as a filmmaker with potential. Gilliam and McKeown shopped the script around Hollywood and found that every studio rejected Brazil. At one point, Twentieth Century Fox agreed to make his script only after Gilliam directed their “A” screenplay at the moment, Enemy Mine. Top directors in Hollywood, such as Steven Spielberg, turned down Enemy Mine (it was later released by Das Boot helmer Wolfgang Petersen in 1985). When Gilliam turned it down, too, Fox then became interested in the project that drove a non-A-List director to turn down an A-List screenplay—it must be something special. On that rationale, Fox agreed to take over international distribution rights for Brazil; falling in line, Universal took over U.S. distribution. Producer Arnon Milchan backed Gilliam’s screenplay throughout the process and saw to it that Gilliam had a $15 million dollar budget, final cut, and a running time of 135 minutes to work with for the U.S. release.

In casting the picture, Gilliam wanted primarily British actors, many of them from earlier Gilliam productions. Jack Lint, Sam Lowry’s friend and The Ministry of Information’s interrogator (a character sought after by De Niro), is given a creepy, chummy disposition by Monty Python regular Michael Palin. The versatile Ian Holm, who played Napoleon Bonaparte in Time Bandits, and whose comic abilities are rarely seen outside of Gilliam films, reteamed with the director as Mr. Kurtzmann. American actress Katherine Helmond, the ogre’s wife in Time Bandits, played Sam’s mother. Several other British actors, such as Bob Hoskins, Jim Broadbent, Ian Richardson, Peter Vaughan, Jack Purvis, and co-writer McKeown, give memorable performances. Finding actors for the lead roles of Sam and Jill proved more extensive. For Jill Layton, the director saw auditions from Kathleen Turner, Jamie Lee Curtis, and Madonna, among others. Gilliam admits Ellen Barkin (Sea of Love and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas) was the most impressive candidate, and she had the role until a last-minute change of mind turned the director toward the virtually unknown Kim Greist. To the director’s dismay, Greist’s audition was better than her on-set performance; she proved incapable of giving Jill the ferocity Gilliam had written for the character. As a result, Greist’s role was trimmed down to focus on Sam.

Another unexpected change occurred when Gilliam searched for Sam Lowry. Gilliam wrote Sam as a youthful hero, and a young Tom Cruise vied for the role. But Cruise, in the U.S., refused to send Gilliam, in London, an audition tape (the director demands that auditions be done on tape, as the camera can pick up subtleties the naked eye cannot). Cruise, according to Gilliam, feared his taped audition might get out after he became a star and all but cried on the phone when Gilliam turned the actor down pending a tape. But after seeing Jonathan Pryce’s audition, Gilliam rethought the Sam character as a middle-aged man locked in a dead-end job. At the time, Pryce was in his late thirties, and the studio thought Gilliam insane for casting such an older and little-known actor in the lead role, but they nonetheless accepted his decision. Pryce’s performance is the heart of the picture: unintentionally heroic, painfully endearing, and absolutely innocent. In another way, he’s a complex man ruled by curious preoccupations just under the surface. Take his mother, whose recurrent plastic surgeries make her younger every time we see her. When Sam finally loses his mind, the boyish character sees his mother and Jill as virtually the same woman. With a childlike innocence in his eyes, Pryce’s Sam is an out-of-depth figure Gilliam compares to Stan Laurel, but Pryce’s physical humor might also recall Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin, mixed with hints of an Oedipal obsession.

When the completed film clocked in at 142 minutes, Fox began distribution throughout Europe, and the film opened to divisive reviews. Universal insisted the director make cuts to honor their agreement for a film 7 minutes shorter. A consummate artist and never a businessman, Gilliam refused; cuts would have sacrificed his vision. Somewhat ignorant of Hollywood deals, he could not understand how 7 minutes mattered so much among “friends.” And so the director’s vision was challenged by Universal President Sidney Sheinberg, resulting in a highly publicized clash, detailed in journalist Jack Mathews’ column in the Los Angeles Times, and then fully documented in Mathews’ book The Battle of Brazil. In Mathews’ account, Sheinberg could substitute The Ministry in Brazil. The executive believed Gilliam’s cut to be bloated and depressing, yet he saw the potential for a commercial picture more “accessible” to audiences. Sheinberg’s intention was to trim the 142-minute cut and release a 94-minute “Love Conquers All” version, wherein everyone lives happily ever after. The exact opposite of Gilliam’s intended thesis for the picture, the happy ending insulted the integrity of Brazil’s message and the director’s vision. In their meetings, Gilliam insisted that if Sheinberg wanted to make cuts, he should place his own name on the film and remove Gilliam’s. After several dramatic phone calls with Sheinberg on the fate of Brazil, Gilliam declared war: On one side, artistic integrity, and on the other, a producer looking to “spare” audiences a bleak message and hopefully sell a few more movie tickets. Gilliam’s intention was to rally support, knowing that if his story became public, undoubtedly sympathy would reside with the David of the story and demonize the Goliath. Gilliam attempted to show critics his version of the film, but Universal denied him approval to show the 142-minute version. Gilliam, on a rebellious whim, took out a full-page ad in Variety that simply read:

Dear Sid Sheinberg,

When are you going to release my film, BRAZIL?

Terry Gilliam.

A move both bold and against traditional hush-hush Hollywood politics, the fate of Brazil received instant public interest. Robert De Niro, who does not traditionally give television interviews, agreed to hit the talk show circuit with Gilliam, using his celebrity as a means for Gilliam to speak out against the proposed rape of his vision. The message was clear: Gilliam wanted blood. The director refused to back down and confronted Sheinberg with what was later called “Guerilla Tactics.” Sheinberg went so far as to say, ironically, that Gilliam saw himself as one of the terrorists in Brazil (forgetting that we never actually see a terrorist in the film). Then, a small revolution began to take place. Los Angeles college campuses arranged lectures and subversive screenings of Gilliam’s cut; the film developed an underground rally movement in which those passionate about artistic freedom had something to stand up for. After seeing the picture in one such covert screening, the Los Angeles Film Critics Association announced that Terry Gilliam’s cut of Brazil was the winner of their annual Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay awards.

Universal finally got the message, and Gilliam’s cut was released. Though the film’s reviews remained mixed around the U.S., audiences were allowed to view a 132-minute version approved by Gilliam. Helping the film along, the Los Angeles Film Critics Association proved that those who write about the film can also influence the industry, exposing the world to one of the most original pieces of cinema ever released. The public response garnered what many expected: audiences looking for sheer entertainment were confused (some described Brazil as a “cinematic rape” of the senses, according to Gilliam), while others revered the picture for its layers, social commentary, and cinematic beauty. Only years later, on home video, would Gilliam’s full 142-minute cut find audiences.

Production battles in Hollywood rarely ever end in favor of the David (i.e. the actor, director, or writer), who is more often than not crushed by the Goliath-sized executive sitting behind a desk, attempting to dictate artistic vision by way of commercial viability. Gilliam’s battle with Sheinberg recalls Orson Welles’ campaign against media tycoon William Randolph Hearst during the production of Citizen Kane (1941). When Hearst heard a rumor that Welles’ motion picture was inspired by events in Hearst’s life, he did everything in his power to stop the production of the film. Hearst offered RKO Radio Pictures nearly a million dollars to destroy all prints and put pressure on the studio, threatening to expose their Jewish heritage to the media. Despite Hearst’s power, Citizen Kane was released, though Hearst refused to allow much-needed advertising in his papers. Citizen Kane failed at the box office and lost the Best Picture Oscar that year to John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley, but it was revisited over the years by critics and film historians and now is oft-cited as the greatest film ever made. Like Gilliam, Welles dealt with outside influences attempting to infiltrate his art throughout his entire career. Citizen Kane was the director’s only success story. Most notably, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), The Lady from Shanghai (1947), Mr. Arkadin (1955), and Touch of Evil (1958)—all masterpieces in their tampered forms—were either reedited without Welles’ permission, had crucial footage burned by crazed executives, or were released in a cut Welles did not approve. In the end, the director walked away with only one motion picture released in his chosen structure; the rest of his career, he was, in one way or another, defeated by The System.

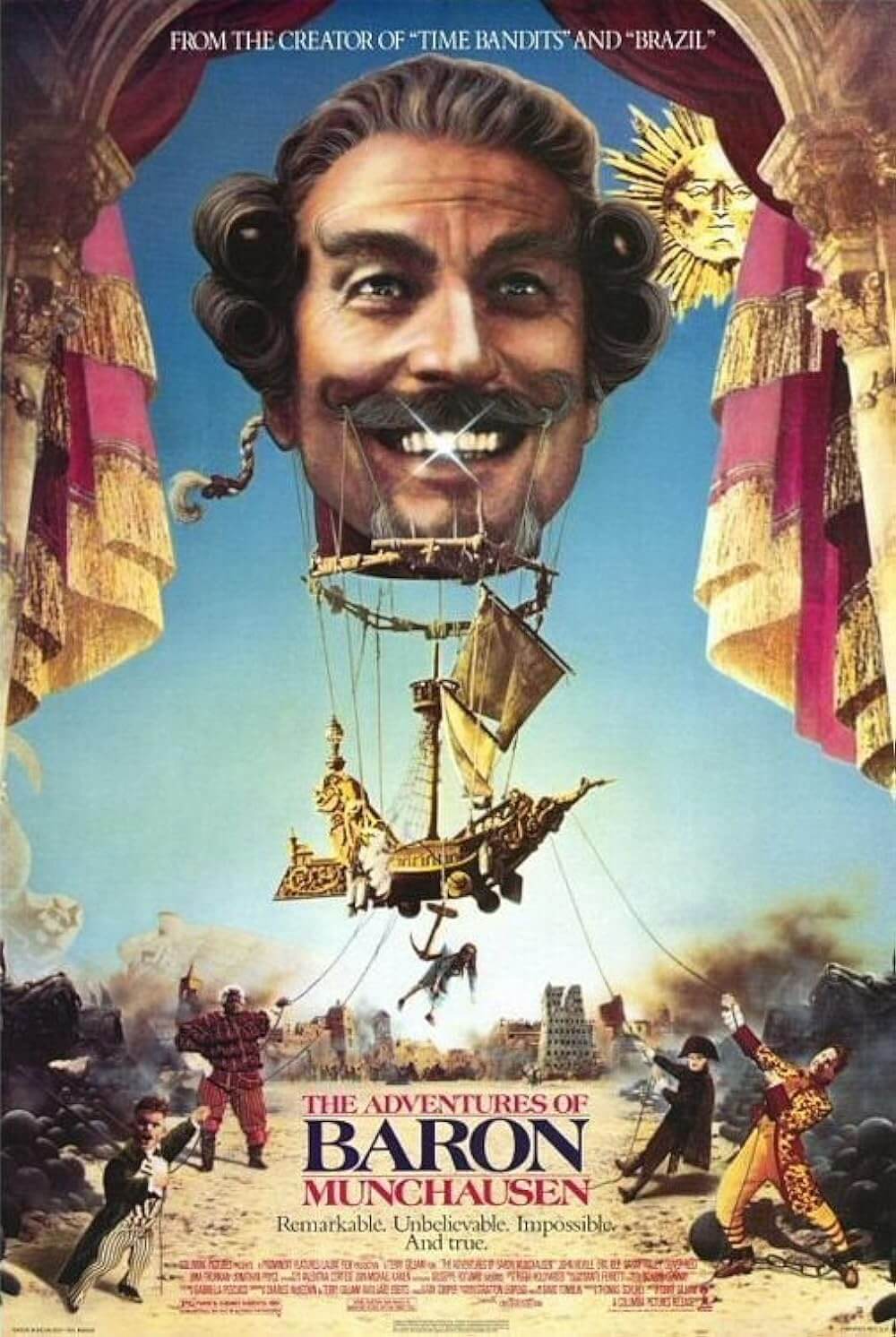

Terry Gilliam’s career follows a similar pattern, outlining a persistent correlation between two master filmmakers and their decisive works. Akin to Citizen Kane, Brazil was the first in an agonizingly long line of troubled productions. After Brazil came the fantastical The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), a production that went exceedingly over budget, endured problems with a pirating and disorganized producer, suffered a corrupt crew and dangerous location shooting, and survived being shut down on several occasions. Minor creative and budgetary disputes gave way to otherwise smoothly run productions of The Fisher King (1991), 12 Monkeys, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), but Gilliam’s most painful blow came during the 2000 production of his unfinished film The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, whose collapsed production is detailed in the documentary Lost in La Mancha (directed by Fulton and Pepe). Busy star Johnny Depp had scheduling limitations, and the weather was painfully uncooperative; their exterior locations were situated near an intolerably loud NATO base; the film’s Don Quixote, Jean Rochefort, suffered a herniated disc; the European-funded budget was drastically cut—all of this in the course of a few weeks, making the shoot an economic impossibility. The production was canceled and the picture remained unmade (until 2019). Lost in La Mancha illustrates how the stigma attached to Gilliam is, in some cases, unjust, as he cannot be blamed for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote’s bad luck setbacks.

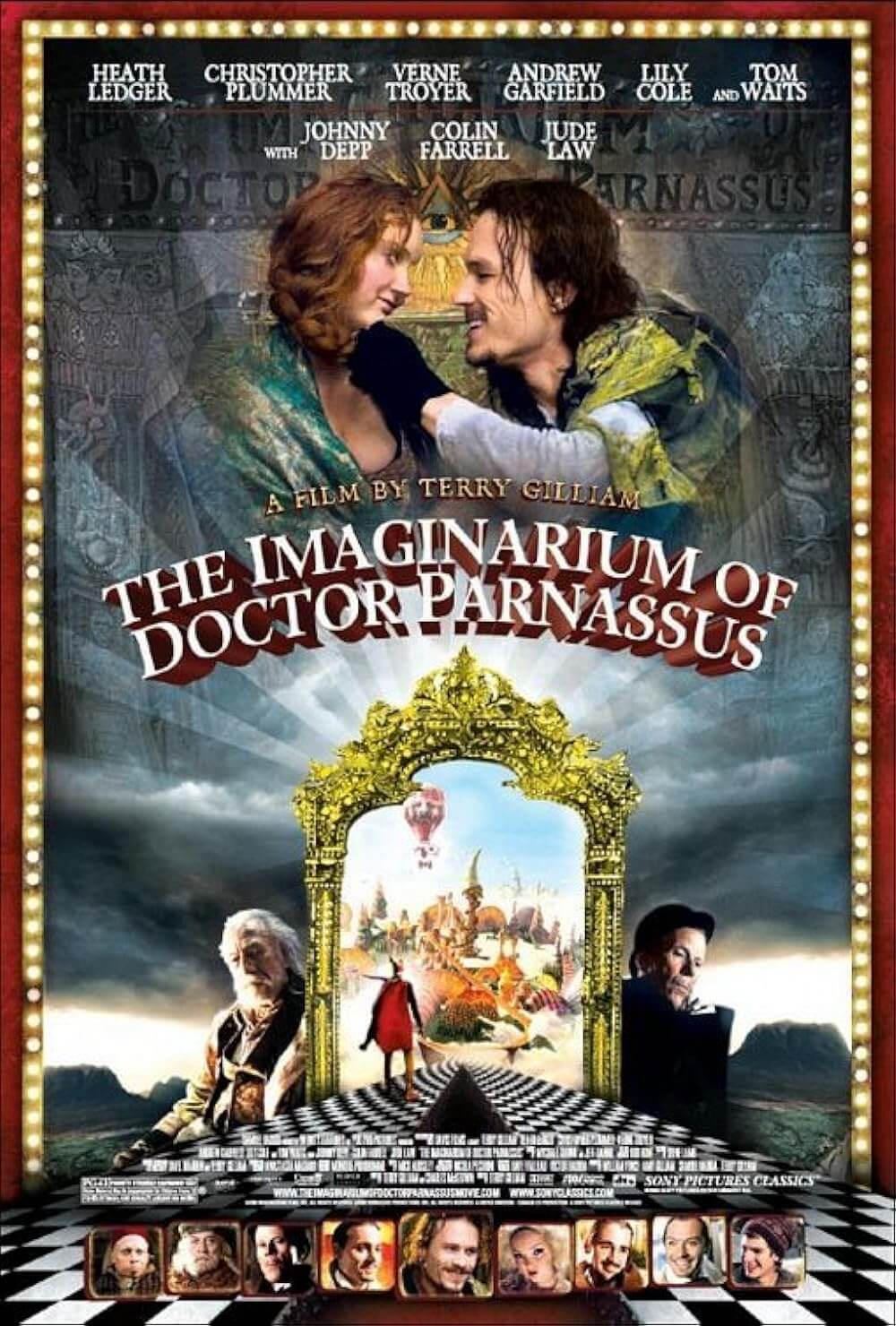

Gilliam’s production troubles did not end there; they followed him like a curse. After the Don Quixote failure, Gilliam directed The Brothers Grimm (2005). Giving him a massive $80 million budget, producers Bob and Harvey Weinstein refused Gilliam regular freedoms and curbed his casting choices, creative flourishes (including a prosthetic nose for star Matt Damon), certain special FX, and final cut. Eventually, Gilliam left the picture before post-production finished to freely film Tideland (2005), a critical failure and otherwise bizarre film. He returned to The Brothers Grimm to lazily complete post-production, no longer caring about the completed product (which is clear upon viewing). Years passed until he was able to begin making The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009), a film which, like Brazil, overcame a seemingly insurmountable obstacle. In the middle of his shoot, star Heath Ledger tragically died, leaving Gilliam and co-writer McKeown to rewrite their script and allow other actors (Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, and Jude Law) to film scenes as the various personalities of Ledger’s character. Though not the film Gilliam intended to make, it remains a deeply personal testament to the director’s innovation and ongoing endurance through years of uneasy filmmaking.

Still, Brazil represents the ultimate example of Gilliam fighting The System and coming out with his original vision intact. In each of the aforementioned completed films, the director sacrificed something, be it a piece of his vision or himself, to release a product not entirely what he wanted. With Brazil, Gilliam’s fight represents a Citizen Kane-type victory; the film succeeded, untouched by the studio, regardless of the attempted tampering, restructuring, and censoring of its message and length. The dream prevailed. This triumph of dreams over reality is a recurring theme in the films of Terry Gilliam, with Brazil being the second picture in what he has often referred to as his “Dream Trilogy,” a free grouping of Time Bandits, Brazil, and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Each film’s main character struggles to reconcile the importance of dreams over hard everyday realities. In Time Bandits, a child escapes from his parents’ house, rotten with technology, into the adventuresome possibilities of history; in Brazil, a middle-aged man escapes reality by way of dreams, substantiates them in reality, and then finds the two cannot coexist; in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, an elderly romantic finds his tall tales are too imaginative and unrealistic for the Age of Reason. In each film, the dreamer is overwhelmed by close-mindedness, astute rationality, and apathetic dogmatism—in other words, reality.

Like many of Gilliam’s works, Brazil is a dramatic tragedy: the protagonist loses his battle. Gilliam illustrates the sad truth that to dream of bringing down or breaking free of The System is hopeless; he even goes so far as to affirm that dreaming begets punishment. Certainly, in Gilliam’s experience, this must be true. A reality of life is that in fights against unjust structures of authority, The System usually wins. While a cynical position, it is more often than not the truth. Gilliam’s feelings in 1985 are perfectly exemplified through an unbelievably detailed production and incomparable vision, and a curious reflectivity between real life and fantasy. The production’s villainous studio executive is tantamount to the film’s Ministry of Information, while Sam Lowry reflects Gilliam’s own quixotic, self-destructive nature. The Citizen Kane of the latter twentieth century, Brazil is the ultimate fatalistic film. It challenges set parameters and the organization built up to keep the individual down. In that, it exposes The System’s faults through wry humor, expressive visuals, and defiant social commentary. Here began Gilliam’s continued personal and professional hardships in filming his dreams, and through characters like Sam Lowry, he continues his pursuits in filmmaking to rebel against any stoic acceptance of dispassion and bureaucracy. His battle is one of imagination, possibility, and hope. The film is ironically, and painfully, more realistic: Brazil understands the need for escape when suppressed by the world’s limitations, but it also acknowledges the despair of dreamy ideals. They are, after all, ideals and, by definition, unreachable.

Bibliography:

Gilliam, Terry. Edited by Ian Christie. Gilliam on Gilliam. London; New York: Faber and Faber, c1999.

Mathews, Jack. The Battle of Brazil: The Nightmare Fantasy Making of the Movie. New York: Applause; Milwaukee, WI: Distributed by Hal Leonard Corp., 1998.

Yule, Andrew. Losing the Light: Terry Gilliam and the Munchausen Saga. New York, NY: Applause Books, c1991.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review