The Definitives

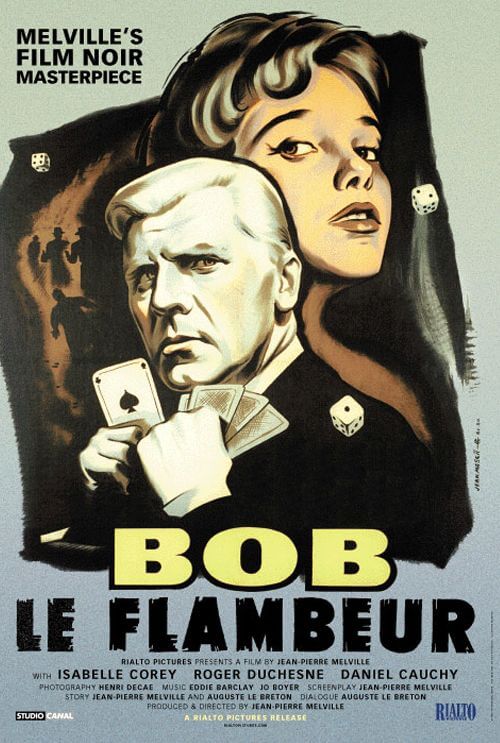

Bob le flambeur

Essay by Brian Eggert |

An alternate title for Bob le flambeur, commonly known as “Bob the Gambler” or “Bob the High Roller”, could be Bob le flâneur. The French term flâneur means a wanderer or stroller, and for writers like Balzac and Baudelaire, only a flâneur could appreciate Paris as they were spectators and participants in the crowd. In the opening scenes of Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1956 film, his first foray into the gangster genre that would later define him, our hero Bob walks the streets of Paris in that hour between night and day, “between heaven and hell” the narrator tells us. The epitome of cool, Bob, played by Roger Duchesne, his white hair slicked back, clad in suit and trenchcoat, stubble on his face after a night of luckless gambling, stops to look at his reflection and chuckles at his rough appearance. One of many Parisian characters on the street this morning, along with an elderly cleaning lady and a young girl who “blossomed early”, Bob is a part of the nameless milieu until Melville, who serves as narrator, points him out.

Everyone knows Bob Montagné, a character Melville would later call “a son of Paris”. His reputation is legend. Before the war, he was a gangster who thrived and treated people with a respect that, when the film opens, he remains famous for—that old school honor among thieves in which modern gangsters are undersupplied. Bob once had enough money to give Yvonne (Simone Paris) a stake for her restaurant in Pigalle, an area renowned for its sordid night life. And then there was the time Bob saved a police inspector, Commissaire Ledru (Guy Decomble), from a criminal’s bullet. But when Bob was captured after carrying out a prominent bank heist, he served some time and his luck tapered as a result. That was 20 years ago. By the time Melville’s film begins, Bob’s legend would precede him if he didn’t remain such an elegant and respected figure. Bob is someone people still root for, even if now his luck has turned him into a constant loser at the tables. Ledru watches out for him where he can, as does Bob’s longtime gangster friend Roger (André Garet), but Bob’s reliance on chance has left him broke.

Now Bob wanders the streets of Paris and makes the rounds at his usual string of nightclubs and restaurants, just eking by but with a poise that sets him apart from the rabble. But then, after learning from a croupier (Claude Cerval) about a scheduled 800 million franc reserve in the Deauville Casino safe on the last day of the Grand Prix, Bob sees an opportunity to reclaim his former renown by plotting a daring heist. With the security lax in the early morning hours between night and day, Bob’s hired crew could enter and hold the staff at bay while their expert safecracker opens the safe. The heist itself is sketched out in a field, the casino’s floor-plan outlined in chalk in the grass. Bob’s crew may not be the brightest, but their tasks are simple, and so too is their scheme. Bob needs only to serve as lookout on the casino floor, and he has promised Roger he will not gamble. The plan is arranged carefully by Bob, who conducts himself with revived criminal professionalism and his signature cool. As the planning ensues, Bob seems to will his own luck back to life. He no longer wanders the city in a haze; rather, he strides toward something that will reinforce what we know about his character: his legend of criminal composure.

Now Bob wanders the streets of Paris and makes the rounds at his usual string of nightclubs and restaurants, just eking by but with a poise that sets him apart from the rabble. But then, after learning from a croupier (Claude Cerval) about a scheduled 800 million franc reserve in the Deauville Casino safe on the last day of the Grand Prix, Bob sees an opportunity to reclaim his former renown by plotting a daring heist. With the security lax in the early morning hours between night and day, Bob’s hired crew could enter and hold the staff at bay while their expert safecracker opens the safe. The heist itself is sketched out in a field, the casino’s floor-plan outlined in chalk in the grass. Bob’s crew may not be the brightest, but their tasks are simple, and so too is their scheme. Bob needs only to serve as lookout on the casino floor, and he has promised Roger he will not gamble. The plan is arranged carefully by Bob, who conducts himself with revived criminal professionalism and his signature cool. As the planning ensues, Bob seems to will his own luck back to life. He no longer wanders the city in a haze; rather, he strides toward something that will reinforce what we know about his character: his legend of criminal composure.

We see a testament to Bob’s character in pouty-lipped seductress Anne (Isabelle Corey), an amateur working girl whom he observes accepting a ride from an American on a scooter early in the film. He notices her again at Yvonne’s and steps in to rescue her from a pimp, Marc (Gerard Buhr), who offers her a job. Bob tells Marc to get lost and invites Anne over to his table, where his young apprentice, Paolo (Daniel Cauchy), who idolizes Bob, takes a liking to her. And though Anne and Paolo connect in a tryst, she remains smitten with Bob and never commits to Paolo in spite of his devotion. She becomes a cigarette girl at a nightclub, and her promiscuity quickly moves her up to a hostess. In one scene, she and Bob dance, and he always knows when to step away before the unspoken sexual tension between them becomes too apparent. For Bob, honor is more important than women. Later, Paolo boasts about their upcoming heist to Anne, who in turn spills to her casual lover, the pimp Marc, who also happens to be a police informer; the message gets to Commissaire Ledru and suddenly the plans for the Deauville have been exposed. When Bob finds out, he scorns Paolo and slaps Anne, but he also leaves Yvonne his house key for the girl, knowing she will need a place to stay after Paolo kicks her out for betraying him. Bob’s basic decency never fails, and that quality remains a recurrent signifier in French gangster films, especially those by Melville.

Born Jean-Pierre Grumbach in 1917, Melville was first introduced to this lifestyle during his time at the Lycée Condorcet school in Paris, where he met a local gang that exposed him to all manner of low-life characters in the criminal underworld. But he also garnered a wealth of influence from his obsession with Hollywood cinema; he had a particular affection for American gangster movies like The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and Out of the Past (1947). For his seventh birthday, his parents bought him a Pathé Baby camera and projector for home use, and he toyed with both endlessly, watching 4-5 films a week, most of them from the states. In 1937 at the start of World War II, he joined the Colonial Calvary and later the Resistance; during that time, he adopted the surname “Melville” after the Moby Dick author. His passion for film, which he later called “opocentric”, resumed when he returned from the war and extended into all things American. He relocated himself on the bohemian Left Bank of Paris, where he received a new education in culture from the surrounding artists and writers. Here he reveled in American culture; later he was known to drive American cars and wear American clothes, his eyes usually hidden behind his signature Ray Bans. Exploring his lifelong cinephilia, Melville published articles in the Cahiers du cinéma and L’Écran français mostly about Hollywood productions and about mise-en-scène before New Wave critics like François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard ever did.

Born Jean-Pierre Grumbach in 1917, Melville was first introduced to this lifestyle during his time at the Lycée Condorcet school in Paris, where he met a local gang that exposed him to all manner of low-life characters in the criminal underworld. But he also garnered a wealth of influence from his obsession with Hollywood cinema; he had a particular affection for American gangster movies like The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and Out of the Past (1947). For his seventh birthday, his parents bought him a Pathé Baby camera and projector for home use, and he toyed with both endlessly, watching 4-5 films a week, most of them from the states. In 1937 at the start of World War II, he joined the Colonial Calvary and later the Resistance; during that time, he adopted the surname “Melville” after the Moby Dick author. His passion for film, which he later called “opocentric”, resumed when he returned from the war and extended into all things American. He relocated himself on the bohemian Left Bank of Paris, where he received a new education in culture from the surrounding artists and writers. Here he reveled in American culture; later he was known to drive American cars and wear American clothes, his eyes usually hidden behind his signature Ray Bans. Exploring his lifelong cinephilia, Melville published articles in the Cahiers du cinéma and L’Écran français mostly about Hollywood productions and about mise-en-scène before New Wave critics like François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard ever did.

Melville’s fascination with cinema prompted his immediate entrance into film-making, as opposed to the natural order in the French film system where a young filmmaker serves as apprentice before he directs on his own. Melville established his own studio, Les Studios Jenner, and operated independently, producing or co-producing the majority of his own projects. His first effort was an 18-minute short about the life of a clown, which gathered enough attention that he was able to finance his next three features: Le silence de la mer (1949), Les enfants terribles (1950), and Quand tu liras cette letter (1953) For his original script Bob le flambeur, necessity required a stylistic shift. His budget was so limited that a normal production schedule could not be set; actors and crew remained on call for when Melville was able to secure additional funds for shooting. A limited number of interiors were filmed at his studio, and Melville opted for an almost neorealist devotion to non-synchronized location shooting as his budget allowed. Under these conditions, the film took a staggeringly long 18 months to complete.

Shooting under such circumstances makes Bob le flambeur an early influence on the New Wave, which did not emerge fully until the late 1950s with the first works from Truffaut (The 400 Blows) and Godard (Breathless). Melville’s inexpensive production shot fast with a small crew, using real people and locations, yet his independence gave him maximum artistic control. These would all become New Wave trademarks, as would other signifiers such as his use of jump cuts and a jazzy score. Melville completed the film for one-tenth the normal budget of the period, and though box-office attendance was only moderate, his film proved profitable due to its low cost. Despite the disjointed production schedule, Bob le flambeur displays a coherent stylistic voice, carefully designed, deliberately paced, and framed with elegant, nostalgic, often noirish compositions courtesy of Melville’s frequent cinematographer Henri Decae. Nevertheless, Cahiers du cinema critics called the film “amateurish” but they admitted “charm comes from its imperfections.” Perhaps their argument could not see beyond the plot, so similar to popular stories from Série noire, a publication dedicated to crime fiction. Not until revivals decades after its release and subsequent to Melville’s increased popularity would the film be hailed as a masterpiece and precursor to the New Wave.

The height of Melville’s popularity came in the 1960s with the international fame that followed his crime pictures Le Doulos (1962), Le Deuxième Souffle (1966), Le Samouraï (1967), and Le Cercle rouge (1970), each dwelling on his frequent themes of conscience, mortality, and existentialist philosophy over religion or politics. His screenplays employ an understated French slang inspired by dialogue in stories by Série noire-published crime authors Auguste le Breton (Touchez pas au grisbi) and Albert Simonin (Rififi), but his handling of the material remains his signature. Although he loved American culture, his films were not mere copies of Hollywood cinema. Instead, Melville followed Hollywood film-making techniques to create his own cinema of true, non-realist invention, and in turn imbued his films with a pointedly French atmosphere and poetic style. Each film is treated with a mannered, calculated flow that points to something more than just gangsters acting cool for the sake of cultural emulation. Behind them is an ingrained philosophy. Some, like Alain Delon in Le Samouraï, follow the Bushido code; others, like Bob, present a symbolic meaning in the quiet gestures and elusiveness Melville so frequently writes for his characters.

The height of Melville’s popularity came in the 1960s with the international fame that followed his crime pictures Le Doulos (1962), Le Deuxième Souffle (1966), Le Samouraï (1967), and Le Cercle rouge (1970), each dwelling on his frequent themes of conscience, mortality, and existentialist philosophy over religion or politics. His screenplays employ an understated French slang inspired by dialogue in stories by Série noire-published crime authors Auguste le Breton (Touchez pas au grisbi) and Albert Simonin (Rififi), but his handling of the material remains his signature. Although he loved American culture, his films were not mere copies of Hollywood cinema. Instead, Melville followed Hollywood film-making techniques to create his own cinema of true, non-realist invention, and in turn imbued his films with a pointedly French atmosphere and poetic style. Each film is treated with a mannered, calculated flow that points to something more than just gangsters acting cool for the sake of cultural emulation. Behind them is an ingrained philosophy. Some, like Alain Delon in Le Samouraï, follow the Bushido code; others, like Bob, present a symbolic meaning in the quiet gestures and elusiveness Melville so frequently writes for his characters.

Unlike many Hollywood film noirs, whose tragic protagonists try to better their future or finally “make it” through some criminal scheme in which they ultimately fail, the French gangster is long-established, and if he endeavors for anything, it is to reclaim the former glory of the past. Characters from Melville’s body of work and his contemporary counterparts, like the adaptations of the aforementioned Touchez pas au grisbi (1954) and Rififi (1955), are reputable or at least long-present in the criminal underworld, rather than trying to break into it. Golden Age Hollywood gangster films, such as The Public Enemy (1931) and Scarface (1932), and even those long after WWII, such as Brian De Palma’s 1983 remake of Scarface or Ridley Scott’s American Gangster (2007), follow the American Dream structure with rags-to-riches plotlines that lead to the corruption of the soul through criminal activity. In Melville’s era, postwar France had become “rotten to the core” thanks to its ruination by the German Occupation, and so his gangster figures become symbols of France’s former brilliance before the war, or at least their yearning for those days.

In this realm, Bob serves as an icon of French identity in his postwar climate, existing as a last remaining flâneur in an era long after the idealized glory days (the “heaven” of the opening narration) that were destroyed by the war. The traditional flâneur could wander and permeate the rich street life offered by Paris and was, as Baudelaire described it, symbolic “of life and the flickering grace of all the elements of life” in this bustling heyday. But this is a view of Paris that Melville never shows us; his story remains set in the seedy underworld of nightclubs and pimps flooding lower Montmartre. In Melville’s imagery, the Occupation represents a period of “hell” that has since passed but from which France has not yet recovered. Bob strolls the Parisian streets, searching for his past Self, trapped in a thorough ambiguity. Though his luck is now gone, he relies on the possibility of his dice and whatever cards he’s dealt—the gamble that is life, and he accepts the arbitrariness and chance of existence—channeling the widespread feeling of meaninglessness extensive in postwar France. In Melville’s hands, the flâneur signifies an ambiguous stature of national identity thrown out-of-joint since the war, ambling seemingly without purpose to find some glint of The City of Lights’ former splendor. And why not make such a deceptively nationalistic film, given his war record Melville remained so secretive about until his death?

In this realm, Bob serves as an icon of French identity in his postwar climate, existing as a last remaining flâneur in an era long after the idealized glory days (the “heaven” of the opening narration) that were destroyed by the war. The traditional flâneur could wander and permeate the rich street life offered by Paris and was, as Baudelaire described it, symbolic “of life and the flickering grace of all the elements of life” in this bustling heyday. But this is a view of Paris that Melville never shows us; his story remains set in the seedy underworld of nightclubs and pimps flooding lower Montmartre. In Melville’s imagery, the Occupation represents a period of “hell” that has since passed but from which France has not yet recovered. Bob strolls the Parisian streets, searching for his past Self, trapped in a thorough ambiguity. Though his luck is now gone, he relies on the possibility of his dice and whatever cards he’s dealt—the gamble that is life, and he accepts the arbitrariness and chance of existence—channeling the widespread feeling of meaninglessness extensive in postwar France. In Melville’s hands, the flâneur signifies an ambiguous stature of national identity thrown out-of-joint since the war, ambling seemingly without purpose to find some glint of The City of Lights’ former splendor. And why not make such a deceptively nationalistic film, given his war record Melville remained so secretive about until his death?

This poetic imagery adopted by Melville gives way to a cosmic twist of fate in the film’s finale, the director’s oddly hopeful message for Paris and the French national identity. When Bob enters the Deauville, he feels lucky. Forgetting his promise to Roger, he begins to gamble, and to his surprise and ours, he begins to win. Lady Luck stays on his side for hours as Bob’s winning streak builds a stack of chips and attracts a small crowd. Meanwhile, Ledru, having tried to warn Bob not to proceed with the heist, with regret assembles his squad to take down Bob’s crew. But Bob has lost track of time; 5 a.m. arrives and he’s just missed the deadline to stop his gang’s advance. Bob quickly cashes in his chips and rushes to make it outside and warn them, and he’s just in time to see Paolo gunned down by the police. The death of Paolo, who has proved himself unworthy of their criminal code after having blabbed to Anne, does not affect Roger and Bob, the two veteran gangsters bound by honor. With indifference to their foiled heist, they watch as casino hands carry out Bob’s millions in winnings. Handcuffed in the back seat of Ledru’s car, Roger remarks that at least now Bob can afford a good lawyer. Bob quips that he might even sue for damages.

In American films, gangsters usually die or go to prison for their crimes, but not Bob. He’s just too damn cool. Melville’s film celebrates Bob’s legend and breathes new life into it, and in symbolic terms it holds hope for France. A certain cheerful spirit overtakes these final scenes that differentiates Bob le flambeur overall from Melville’s other, decidedly moodier gangster pictures. Though Melville’s philosophy of cool plays a crucial role in this film, Bob’s devotion to gambling, chance, and the happenstance of fate is finally the character’s enduring optimism. He keeps trying again and again in hopes of winning, not because of some scummy gambling addiction or detrimental character flaw, but because he remains hopeful about the future. Finally, just before he leaves for the casino on the night of the heist, Bob opens a drawer and look at his gun; he resolves to leave it. If he hadn’t, no doubt the film’s ending would be more like an American gangster film. And so, Bob le flambeur assumes a particular and unique outlook to both Melville and Hollywood’s crime cinema—a philosophy where criminality becomes the theater of the absurd in which one’s devotion to their values leads not to their poetic death, but instead to their ironic victory. This humorous quirk has ingrained the film’s own legend, later informing Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s trilogy, heavily influencing Paul Thomas Anderson’s Hard Eight (1996), and inspiring Neil Jordan to remake it in 2002 under the title The Good Thief, starring Nick Nolte in the role of Bob.

In American films, gangsters usually die or go to prison for their crimes, but not Bob. He’s just too damn cool. Melville’s film celebrates Bob’s legend and breathes new life into it, and in symbolic terms it holds hope for France. A certain cheerful spirit overtakes these final scenes that differentiates Bob le flambeur overall from Melville’s other, decidedly moodier gangster pictures. Though Melville’s philosophy of cool plays a crucial role in this film, Bob’s devotion to gambling, chance, and the happenstance of fate is finally the character’s enduring optimism. He keeps trying again and again in hopes of winning, not because of some scummy gambling addiction or detrimental character flaw, but because he remains hopeful about the future. Finally, just before he leaves for the casino on the night of the heist, Bob opens a drawer and look at his gun; he resolves to leave it. If he hadn’t, no doubt the film’s ending would be more like an American gangster film. And so, Bob le flambeur assumes a particular and unique outlook to both Melville and Hollywood’s crime cinema—a philosophy where criminality becomes the theater of the absurd in which one’s devotion to their values leads not to their poetic death, but instead to their ironic victory. This humorous quirk has ingrained the film’s own legend, later informing Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s trilogy, heavily influencing Paul Thomas Anderson’s Hard Eight (1996), and inspiring Neil Jordan to remake it in 2002 under the title The Good Thief, starring Nick Nolte in the role of Bob.

By the end of the film, Bob finally becomes “Bob le flambeur” again, a high roller and man who lives up to his legend. This is perhaps a hopeful message for postwar France, one that anticipates the coming New Wave and reclamation of French identity lost in the war. He remains a figure to celebrate and remember, like one of Melville’s beloved Hollywood screen characters (Humphrey Bogart’s Rick from Casablanca comes to mind), because Melville’s film operates within the strictures of cinematic nostalgia. Bob is the singular example of Melville’s style, both a product of American iconography, yet rooted in a certain French mysticism and poetry. The character embodies a series of recognizable gangster gestures, smoking his cigarettes a particular way or driving around Paris in an American convertible; he is the honorable gangster who, like so many Melville gangsters, is nonetheless alone, melancholy, and vulnerable. In a way, he is more a character type, a combination of iconic cinema ideas than a fully developed personality. And yet, Melville spends far more screentime establishing Bob than he does the ensuing heist scenario. Bob le flambeur becomes an exercise in myth-making, reinforcing and refiltering the Hollywood cinema the director so adored through his own creative drives, into the self-conscious construction of a cherished screen legend.

Bibliography:

Nupert, Richard. A History of the French New Wave. Second Edition. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2007.

Vincendeau, Ginette. Jean-Pierre Melville: An American in Paris. London: British Film Institute, 2003.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review