The Definitives

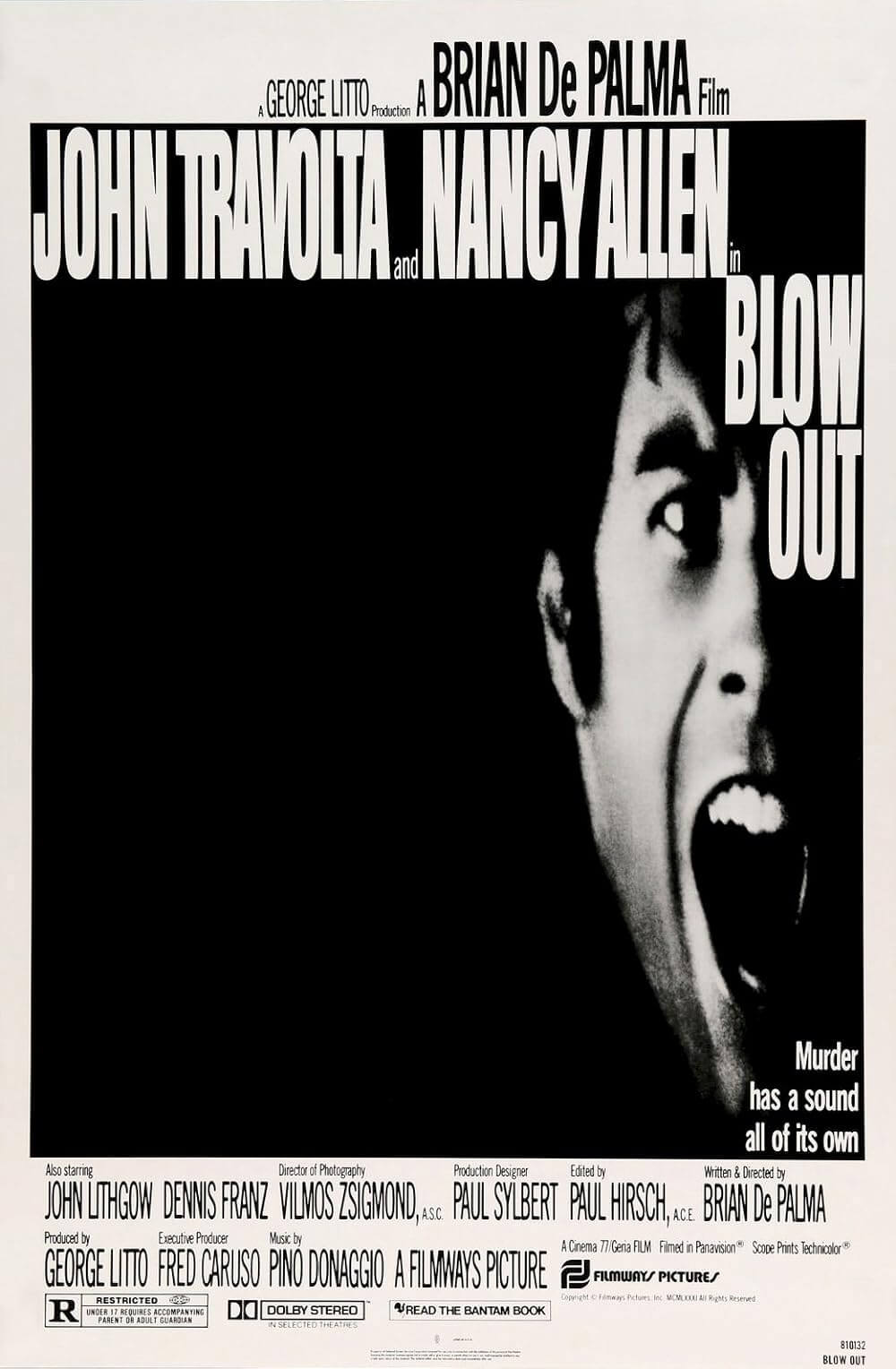

Blow Out

Essay by Brian Eggert |

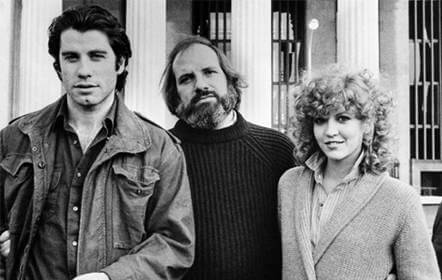

Brian De Palma’s Blow Out begins with a slick sequence from a killer’s point of view, similar to the subjective opening in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). A voyeuristic, heavy-breathing killer watches young, mostly topless college girls in their dorm as they undress, dance, and behave like fantasy college girls often do. Then, he makes his way inside and follows his chosen victim into the shower. His knife now in the frame, he pulls back the curtain for a campy Norman Bates moment only to be greeted by an underwhelming damsel “eek!” This is footage for a B-movie slasher called “Coed Frenzy,” and sound-effects man Jack Terry is tasked with taping the ineffectual screams of second-rate performers, each chosen for their bust size over their acting talents. Jack’s producer burdens him to find a perfect guttural scream for the movie, a shriek that feels authentic and rings with terror. But by the film’s haunting finale, when Jack finally records the desired scream, De Palma has shattered the comic triviality of the opening sequence and confronted the viewer with the appalling truths of film-making and film-watching.

Blow Out is pure cinema, an exercise in elegant direction and refined style in which technique and plot merge into a singular body. And yet, the picture goes beyond pure cinema to question the mechanics of filmmaking. Outwardly, it contains all the traits of a great thriller, with plot strains involving a mystery, a rash of murders, and a vast political conspiracy. Viewed on those terms alone, the film is no less an impressive piece of entertainment. Under these surface elements, however, resides an exploration into the power of filmmaking and what sound and image can reveal—or conceal—when cut and spliced together. De Palma, a director whose films are relentlessly linked to those of Alfred Hitchcock, has been accused of imitating the cinematic grammar of Hitchcock and other directors. And though De Palma’s signatures are often undeniably Hitchcockian in their intertextuality and polish, he goes beyond Hitchcock’s model with Blow Out, putting forth his own integrated obsessions. These obsessions, present throughout his career, define his originality and importance as an auteur, and through them, De Palma demands an investigation of cinema itself.

De Palma emerged in the late 1960s fresh out of film school with extensive knowledge of cinema history and film theory, and—along with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, and John Carpenter—became a progressive member of his era’s New Hollywood directors to project their cinematic knowhow onscreen. Though perhaps less widely known and honored; he’s certainly less commercially successful than his contemporaries, and his contributions to the art form are considerable. He can be credited with discovering Robert De Niro with his early experimental film Greetings (1968) and its expansion piece Hi, Mom! (1970); his early work encouraged Terrence Malick (The Thin Red Line) to pursue filmmaking; much later, he inspired Quentin Tarantino to do the same. Yet, more than any other director of his generation, he remains dedicated to making movies about movies both directly and indirectly throughout the years. As a result, an arsenal of cinematic trickery and thematic fixations occupy “A Brian De Palma Film.”

De Palma emerged in the late 1960s fresh out of film school with extensive knowledge of cinema history and film theory, and—along with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, and John Carpenter—became a progressive member of his era’s New Hollywood directors to project their cinematic knowhow onscreen. Though perhaps less widely known and honored; he’s certainly less commercially successful than his contemporaries, and his contributions to the art form are considerable. He can be credited with discovering Robert De Niro with his early experimental film Greetings (1968) and its expansion piece Hi, Mom! (1970); his early work encouraged Terrence Malick (The Thin Red Line) to pursue filmmaking; much later, he inspired Quentin Tarantino to do the same. Yet, more than any other director of his generation, he remains dedicated to making movies about movies both directly and indirectly throughout the years. As a result, an arsenal of cinematic trickery and thematic fixations occupy “A Brian De Palma Film.”

Each De Palma picture contains undeniable precision and control; they are executed with incredible attention to detail. Nothing in a De Palma film is random or out of place; rather, each work feels carefully composed and intentional. His formal choices emphasize their own presence, reminding the viewer that cinema is not reality: He uses split screens, bird’s eye view shots, Dutch angles, point-of-view camera perspectives, split diopter lenses, and long tracking shots performed with Steadicam equipment. Every element in De Palma’s frame has been considered; he often shoots in deep focus and activates his entire depth of field—and so there always seems to be someone listening in on the conversation in the backdrop or looking on from afar. Frequently, they have some role to play later on. Time and again, his approach, though Hitchcockian in its technical flawlessness, combines formal artistry with visceral subject matter; with a few rare exceptions, De Palma’s films are rooted in crimes and sexuality. Prostitutes and gaze-stricken men are recurrent characters in his films. With his camera so often dwelling on a sexualized feminine object, he invites accusations of misogyny that, in several cases, leave his work difficult to defend. His exploitative intentions and sporadic missteps aside, De Palma’s approach balances artistry and craft with confidence found only in the most preeminent filmmakers.

De Palma often takes inspiration from a classic, often with enough lucidity to make his sources readable, occasionally downright obvious. And though traditionally such a quality would be described as derivative, if not accused of outright artistic plagiarism, De Palma remains an auteur of influences. He adopts the stylistic or narrative traits of Michael Powell, Howard Hawks, Michelangelo Antonioni, and most routinely Hitchcock, incorporating aspects of his most beloved filmmakers into his own work. His reinterpretive approach takes his own artistic inspiration and adoration for cinema, and he turns them into something altogether new. De Palma achieves a rare balance between inspiration and homage that results in a true original. Much like Tarantino or Paul Thomas Anderson, he belongs on a shortlist of filmmakers who innovate on established material for a wholly distinctive, rather brilliant, post-modern style. And so, born from Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and by extension Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), De Palma’s Blow Out, released in 1981, has been saturated in these searching, ambiguous sources and presented with a Hitchcockian sheen.

De Palma often takes inspiration from a classic, often with enough lucidity to make his sources readable, occasionally downright obvious. And though traditionally such a quality would be described as derivative, if not accused of outright artistic plagiarism, De Palma remains an auteur of influences. He adopts the stylistic or narrative traits of Michael Powell, Howard Hawks, Michelangelo Antonioni, and most routinely Hitchcock, incorporating aspects of his most beloved filmmakers into his own work. His reinterpretive approach takes his own artistic inspiration and adoration for cinema, and he turns them into something altogether new. De Palma achieves a rare balance between inspiration and homage that results in a true original. Much like Tarantino or Paul Thomas Anderson, he belongs on a shortlist of filmmakers who innovate on established material for a wholly distinctive, rather brilliant, post-modern style. And so, born from Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and by extension Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), De Palma’s Blow Out, released in 1981, has been saturated in these searching, ambiguous sources and presented with a Hitchcockian sheen.

Antonioni’s existentialist thesis-of-a-film was a sensation celebrated for its vagueness and numerous possible readings upon its release. Blow-Up follows a narcissistic photographer who snaps a shot that may contain evidence of a murder. The photographer investigates by enlarging the image and returning to the scene for clues. Still, the more he examines and amplifies the photo, the more distorted it becomes—and the more it allows meaning to be projected onto it. The involved parties propel his paranoia when they seize all picture evidence, while Antonioni’s direction forces the audience to scrutinize minor details and draw their own conclusions. In a similar scenario, except with audio as the central medium, The Conversation involves a wire-tapper who records a vague exchange that seems to contain discussion of a murder scheme after closer inspection of the tape. Unlike Blow-Up, Coppola’s film vindicates the protagonist’s suspicions when he confronts the conspirators. Even so, his justified obsession leaves him overcome by the same paranoia that first propelled his compulsive quest for answers.

Blow Out contains similar themes of obsession and paranoia with a protagonist who manipulates photos and audio to reveal the dangerous secrets inside. While at a Philadelphia park one night, John Travolta’s Jack Terry records new stock sound effects—shown with the clever application of De Palma’s oft-used split diopter lenses to connect the noise and its source—and witnesses a speeding car experience a blowout and swerve uncontrollably into a nearby lake. He swims to the rescue and saves a young woman, Sally Bedina (Nancy Allen), from drowning, but the other passenger goes down the car. Later, Jack learns the unfortunate passenger he couldn’t save was future presidential Governor McRyan. When Jack goes back and listens to the audio he recorded from the incident more closely, he slows down the audio and hears what he believes to be a gunshot that disabled the Governor’s car, causing the accident. Faced with a potential conspiracy and an assassination attempt, Terry, a former wiretapper for the police, learns that by chance, a photographer, Manny Karp (Dennis Franz), had recorded the event on film. Terry obtains stills from Karp’s footage from a local tabloid and combines it with his audio, and the outcome reinforces Terry’s theory but doesn’t prove it. The whole incident involving the Governor’s car in the lake remains unclear without Karp’s original negative.

Blow Out contains similar themes of obsession and paranoia with a protagonist who manipulates photos and audio to reveal the dangerous secrets inside. While at a Philadelphia park one night, John Travolta’s Jack Terry records new stock sound effects—shown with the clever application of De Palma’s oft-used split diopter lenses to connect the noise and its source—and witnesses a speeding car experience a blowout and swerve uncontrollably into a nearby lake. He swims to the rescue and saves a young woman, Sally Bedina (Nancy Allen), from drowning, but the other passenger goes down the car. Later, Jack learns the unfortunate passenger he couldn’t save was future presidential Governor McRyan. When Jack goes back and listens to the audio he recorded from the incident more closely, he slows down the audio and hears what he believes to be a gunshot that disabled the Governor’s car, causing the accident. Faced with a potential conspiracy and an assassination attempt, Terry, a former wiretapper for the police, learns that by chance, a photographer, Manny Karp (Dennis Franz), had recorded the event on film. Terry obtains stills from Karp’s footage from a local tabloid and combines it with his audio, and the outcome reinforces Terry’s theory but doesn’t prove it. The whole incident involving the Governor’s car in the lake remains unclear without Karp’s original negative.

Meanwhile, De Palma injects his film with slasher suspense from what at first seems to be an unconnected string of murders by the “Liberty Bell Strangler” in the Philadelphia area. A sinister killer, Burke (John Lithgow, in his most chilling performance outside of De Palma’s own Raising Cain from 1992), strangles prostitutes and leaves a sloppy Liberty Bell carved into their flesh. But it’s all a smokescreen. In fact, Burke has been hired to kill Sally, the call girl hired by Governor McRyan. To make Sally’s death seem unconnected to the political assassination she witnessed, Burke kills several other women, treating the murders as no more than a bonus to the job he was hired to do. And yet, Burke takes unquestionable satisfaction from his killings in a frightening way. He’s a pure maniac devoid of backstory or motivations other than bloodlust, and he’s an incredibly effective villain—a pure force of unquestionable evil. At the same time, Jack pursues his curiosity and questions Sally about the incident, learning that Sally was hired to bed McRyan. He also learns that Karp, an expert at snapping illicit photos, captured footage for an intended smear campaign. Though, neither player was expecting an assassination. And even with Jack’s audio proof, authorities refuse to believe his conspiracy theory; just seven years after Watergate, everyone wants to believe the politician’s death was accidental.

Jack is an idealist hero, determined to protect an innocent and expose the truth. Of course, he falls for Sally, a character intentionally naïve and weak and used by everyone around her. He eventually enlists her to acquire Karp’s original footage, and with it, using sound and image, he creates a complete picture of the gunshot preceding the blowout. With this, Jack contacts a reporter who promises to air the details of Jack’s conspiracy theory alongside his newly assembled footage. Sally arranges to meet the press contact at a train station, and Jack wires her to listen in from a distance. The scene is tense since we’ve learned that, years earlier, one of Jack’s wires botched an investigation into police corruption and got a detective killed. Jack has taken every precaution. Surveying from a distance, Jack loses them on a subway just when he begins to suspect the reporter, while the audience can already see Burke has taken the reporter’s place. “Liberty Day” celebrations and exuberant crowds slow Jack’s desperate race to reach Sally, who he can hear in an earpiece calling for help. Jack arrives with Sally’s last screams as Burke carves up another victim of the “Liberty Bell Strangler.” Too late, Jack kills Burke, and with him the only evidence of his conspiracy theory. But tragic irony leaves him with a perfect scream recorded for “Coed Frenzy.”

Jack is an idealist hero, determined to protect an innocent and expose the truth. Of course, he falls for Sally, a character intentionally naïve and weak and used by everyone around her. He eventually enlists her to acquire Karp’s original footage, and with it, using sound and image, he creates a complete picture of the gunshot preceding the blowout. With this, Jack contacts a reporter who promises to air the details of Jack’s conspiracy theory alongside his newly assembled footage. Sally arranges to meet the press contact at a train station, and Jack wires her to listen in from a distance. The scene is tense since we’ve learned that, years earlier, one of Jack’s wires botched an investigation into police corruption and got a detective killed. Jack has taken every precaution. Surveying from a distance, Jack loses them on a subway just when he begins to suspect the reporter, while the audience can already see Burke has taken the reporter’s place. “Liberty Day” celebrations and exuberant crowds slow Jack’s desperate race to reach Sally, who he can hear in an earpiece calling for help. Jack arrives with Sally’s last screams as Burke carves up another victim of the “Liberty Bell Strangler.” Too late, Jack kills Burke, and with him the only evidence of his conspiracy theory. But tragic irony leaves him with a perfect scream recorded for “Coed Frenzy.”

While Blow-Up and The Conversation (whose respective visual and aural themes are spliced together here) inspired Blow Out’s plot, there are moments in the film, and all through De Palma’s career, where both the style and plotting in his work seems to channel the very being of Alfred Hitchcock. Hitchcock began his career with tales of murder and spies, and with time and increased popularity, his work became more complex in terms of narrative and execution. At the end of his career, Hitchcock’s output had reached heights of form and technical artistry, while his stories dwelled on notions of violent men inflicting their sexual obsessions on women. Titles like Vertigo (1958), Psycho (1960), Marnie (1964), and Frenzy (1972) each contain such themes, growing more potent in their descriptions as the industry’s tolerance for explicit material grew. De Palma’s filmmaking materializes from Hitchcock’s and takes the next step forward, as though Hitchcock’s spirit inhabited De Palma and continued to explore the same themes in more potent detail. As a result, Del Palma’s best work, from the middle part of his career, adopts Hitchcockian subject matter and techniques, while his intermittent failures lack such stylization.

Indeed, many of De Palma’s films find their roots in Hitchcock homage and propel the perception that De Palma is little more than a Hitchcock imitator, beginning with Sisters (1973), wherein, recalling the second half of Psycho, a snooping reporter pokes around for answers in a sequence straight out of Rear Window (1954), and finds that one of two double-ringer twins has murderous tendencies. In Obsession (1976), De Palma borrows heavily from Vertigo for the first time in a tale about a man in love with a woman that resembles his late wife. His most intensely (and cleverly) Hitchcockian work remains Dressed to Kill (1980), which opens like a Vertigo–inspired voyeur tale (complete with a wonderful, wordless museum pursuit sequence) and closes with a Psycho-esque shower scene. Body Double (1984) offers a mirror image of Rear Window. John Lithgow plays another maniac in Raising Cain (1992), influenced heavily by Psycho, down to a psychologist detailing, in exceedingly clinical terms, the warped mental state of the killer. Finally, the underrated Snake Eyes (1996), a film closely linked to Blow Out, borrows its incredibly fluid opening tracking shot from Rope, Hitchcock’s drama comprised of only a handful of extended shots. These examples are only a few, where further evidence appears even in De Palma’s more popularized films: The Untouchables (1987), Mission: Impossible (1996), and even Scarface (1983).

De Palma’s oeuvre seems split between overtly Hitchcockian-themed works and titles that employ technical precision worthy of Hitchcock (for example, The Bonfire of the Vanities and Carlito’s Way). Given this enduring connection, De Palma has often been criticized for repeatedly returning to the Master of Suspense for inspiration. But then, is emulating Hitchcock really a problem in purely cinematic or storytelling terms? Or do De Palma’s detractors merely resent the notion of open-faced homage (or De Palma’s proven ability to execute such an homage with inspired care)? When so many filmmakers try and fail to capture Hitchcock’s talent in their films, De Palma’s controlled stylization remains second only to Hitchcock himself. There are moments in Dressed to Kill and Body Double where the arrangement feels so pitch-perfect that we begin questioning the possibilities of transmigration. Then again, Hitchcock’s films present only the vocabulary for De Palma to reinterpret into a new cinematic lexis both critical of and enamored with what cinema can do. In this regard, Blow Out is the filmmaker’s masterwork by employing all the themes and stylization of a Hitchcock picture, but without any direct story references to Hitchcock films.

De Palma’s oeuvre seems split between overtly Hitchcockian-themed works and titles that employ technical precision worthy of Hitchcock (for example, The Bonfire of the Vanities and Carlito’s Way). Given this enduring connection, De Palma has often been criticized for repeatedly returning to the Master of Suspense for inspiration. But then, is emulating Hitchcock really a problem in purely cinematic or storytelling terms? Or do De Palma’s detractors merely resent the notion of open-faced homage (or De Palma’s proven ability to execute such an homage with inspired care)? When so many filmmakers try and fail to capture Hitchcock’s talent in their films, De Palma’s controlled stylization remains second only to Hitchcock himself. There are moments in Dressed to Kill and Body Double where the arrangement feels so pitch-perfect that we begin questioning the possibilities of transmigration. Then again, Hitchcock’s films present only the vocabulary for De Palma to reinterpret into a new cinematic lexis both critical of and enamored with what cinema can do. In this regard, Blow Out is the filmmaker’s masterwork by employing all the themes and stylization of a Hitchcock picture, but without any direct story references to Hitchcock films.

De Palma famously contradicted Jean-Luc Godard’s axiom “Photography is truth. And cinema is truth 24-frames-a-second” when he said, “The camera lies all the time; lies 24-times-per-second”. His antagonism toward cinematic truth unreserved, De Palma’s belief has never been realized to more lucid or compelling effect than with Blow Out. Both onscreen and behind the camera, he demonstrates how sound and image are assembled into an elaborately conceived deception. Moviegoers instinctually believe what they see and hear. But De Palma challenges viewers to question their senses and consider the process of filmmaking, how through a few simple cuts, video and audio are shaped into narrative or propaganda. To expose these concepts in narrative form, De Palma integrates themes of political corruption and American iconography into the mise-en-scène of the film, allowing him to make the crucial connection between filmmaking and the reliance on video and audio to create political propaganda within the American media.

For example, Blow Out’s climax is loaded with the patriotic visual trappings of Liberty Day festivities. The signs are everywhere, from Liberty Bells sliced into prostitutes to De Palma saturating his frame with American reds and blues. None is so powerful as the shocking image of Sally crying for help with a massive American flag consuming the backdrop. And though De Palma avoids direct references to the historical foundations of his plot—the Chappaquiddick incident, Watergate, and the JFK assassination—the film’s grim conclusion implies the characters are victims of conspiring political powers. But De Palma never resorts to preachy messages on corruption; his mise-en-scène does the work enough that the political undercurrents in Blow Out could be forgotten altogether next to its thrills and chills. De Palma never forgets that his yarn is about Jack finding his scream, so while he exploits the political imagery to thrust the plot forward, he ends his picture with Jack, back in the seedy B-movie studio, watching the film’s opening shower scene, now with Sally’s cries looped-in to haunting effect. “Good scream,” he says, defeated. “Good scream.” On a most perceptible level, De Palma remarks that the naïve and idealistic few who still blindly believe in honest American politics, despite the ongoing scandals and cover-ups, are victims of the political machine, just as Jack and Sally have become.

For example, Blow Out’s climax is loaded with the patriotic visual trappings of Liberty Day festivities. The signs are everywhere, from Liberty Bells sliced into prostitutes to De Palma saturating his frame with American reds and blues. None is so powerful as the shocking image of Sally crying for help with a massive American flag consuming the backdrop. And though De Palma avoids direct references to the historical foundations of his plot—the Chappaquiddick incident, Watergate, and the JFK assassination—the film’s grim conclusion implies the characters are victims of conspiring political powers. But De Palma never resorts to preachy messages on corruption; his mise-en-scène does the work enough that the political undercurrents in Blow Out could be forgotten altogether next to its thrills and chills. De Palma never forgets that his yarn is about Jack finding his scream, so while he exploits the political imagery to thrust the plot forward, he ends his picture with Jack, back in the seedy B-movie studio, watching the film’s opening shower scene, now with Sally’s cries looped-in to haunting effect. “Good scream,” he says, defeated. “Good scream.” On a most perceptible level, De Palma remarks that the naïve and idealistic few who still blindly believe in honest American politics, despite the ongoing scandals and cover-ups, are victims of the political machine, just as Jack and Sally have become.

But De Palma’s political thriller surface in Blow Out has the same pretense as Tarantino’s World War II setting in Inglourious Basterds (2009). Both films inhabit common cinematic genres to make a greater commentary on filmmaking. Consider the title sequence of De Palma’s film, a clever split-screen image of a news broadcast on one-half, and Jack listening to and labeling a series of audio tapes on the other half. As the anchors report on Governor McRyan’s appearance at the “Liberty Day Ball,” Jack logs the insignificant sound effects of footsteps and breaking glass. The sequence culminates when Jack plays a gunshot effect, which is juxtaposed against McRyan’s quote about a hopeful future. Finally, Jack catalogs the plop of a body hitting the ground, the effect delightfully macabre in its implications, and a wonderfully suggestive use of split screens and editing. This would not be the last time De Palma used multiple images to evoke a political message. In his 2007 film Redacted, he uses a mixture of security camera footage, internet videos, digital camera recordings, and surveillance video to tell the story of an Arab girl raped and murdered by American soldiers serving in Iraq, and its powerful anti-war repercussions ponder the dehumanization of American soldiers.

De Palma’s unapologetic slasher Dressed to Kill ended with a shower scene, not unlike the one that opens Blow Out. Nancy Allen’s heroine receives the Psycho treatment from a subjective camera killer, only to awaken from her nightmare disturbed but unharmed. Unfortunately, that feeling of safety bestowed by filmic catharsis has no place in Blow Out. The film’s first scene trivializes such catharsis, thus proclaiming its dramatic intentions, whereas Dressed to Kill was mere escapist fun. Conceptually his most serious, tragic, and politically minded work to date, the film balances formal daring and emotional involvement, although the director’s works are often only the former. However, the dark sentiments punctuated by the catastrophic conclusion guaranteed Blow Out’s failure at the box office, as De Palma refuses to restore the audience’s sense of safety in the finale. In that regard, De Palma detracted from the Hitchcockian model with Blow Out, as so many Hitchcockian thrillers quickly restore our sense of safety in the final moments. And despite passionate reviews from the occasional critic—Pauline Kael and Roger Ebert wrote enthusiastic appraisals—the film, much like Hitchcock’s Vertigo, received cold responses, only to later be called the director’s greatest achievement.

De Palma’s unapologetic slasher Dressed to Kill ended with a shower scene, not unlike the one that opens Blow Out. Nancy Allen’s heroine receives the Psycho treatment from a subjective camera killer, only to awaken from her nightmare disturbed but unharmed. Unfortunately, that feeling of safety bestowed by filmic catharsis has no place in Blow Out. The film’s first scene trivializes such catharsis, thus proclaiming its dramatic intentions, whereas Dressed to Kill was mere escapist fun. Conceptually his most serious, tragic, and politically minded work to date, the film balances formal daring and emotional involvement, although the director’s works are often only the former. However, the dark sentiments punctuated by the catastrophic conclusion guaranteed Blow Out’s failure at the box office, as De Palma refuses to restore the audience’s sense of safety in the finale. In that regard, De Palma detracted from the Hitchcockian model with Blow Out, as so many Hitchcockian thrillers quickly restore our sense of safety in the final moments. And despite passionate reviews from the occasional critic—Pauline Kael and Roger Ebert wrote enthusiastic appraisals—the film, much like Hitchcock’s Vertigo, received cold responses, only to later be called the director’s greatest achievement.

Unlike the brooding and sometimes abstract puzzle work of the films that inspired it, Blow Out resolves to entertain and engage its audience in the classic Hitchcockian sense. On one level, the film could be viewed as merely an involved thriller; on another, it shows De Palma dissecting his craft so his audience can better comprehend it from a technical perspective—to understand how these processes feed and manipulate the narrative. He shows his audiences how sound and image are assembled into cinema, how a better understanding of the two metonyms and their construction leads to a healthy skepticism of the completed metaphor. By way of plot, the audience comes to grasp cinema’s influence as not merely a frivolity but a prominent and potentially dangerous art form that wields considerable propagandistic power in the right hands. De Palma transcends his thematic and stylistic sources by incorporating their themes into a yarn that reaches a larger audience through its basic thriller setup and, from the plot’s many implications, leaves his audience to consider how films are made, the relationship between a film and its viewer, and the frighteningly deteriorating line between reality and reality on film.

Bibliography:

Blackford, James. “Dressed to Kill and Blow Out.” Sight and Sound 23, no. 9 (September 2013): 96.

Keesey, Douglas. Brian De Palma’s Split-Screen. Mississippi: The University Press of Mississippi, 2015.

Peretz, Eyal. Becoming Visionary: Brian De Palma’s Cinematic Education of the Senses. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review