The Definitives

Blade Runner (1982)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Science-fiction is about creating intricate worlds and using those worlds to emphasize a discernible difference from our own. Whether the differences are political, societal, or technological, the genre is designed to bring our world into question. Ridley Scott layers Blade Runner, his science-fiction masterpiece from 1982, with a ravishing visual structure and a measureless sense of vision, both aesthetically and philosophically, and creates a cinematic world that not only brings our world into question but questions everything we perceive. Scott’s film was based on author Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. Dick was famous for creating worlds for himself both on the page and off; plagued by schizophrenia and paranoia, he suffered from hallucinations that informed his fiction and complicated his personal life. He was an expert at creating worlds, albeit intentionally or not. Although Dick never saw a completed version of Blade Runner, he wrote about some of what he saw in its marketing materials. The Official Collector’s Edition of the “Blade Runner” Souvenir Magazine included this blurb by the author: “All I can say is that the world in Blade Runner is where I really live. That is where I think I am anyway. This world will now be a world that every member of the audience will inhabit. It will not be my private world. It is now a world where anyone who will go into the theater and sit down and watch the film will be caught up and the world is so overpowering, it is so profoundly overpowering that it is going to be very hard for people to come out of it and adjust to what we normally encounter.”

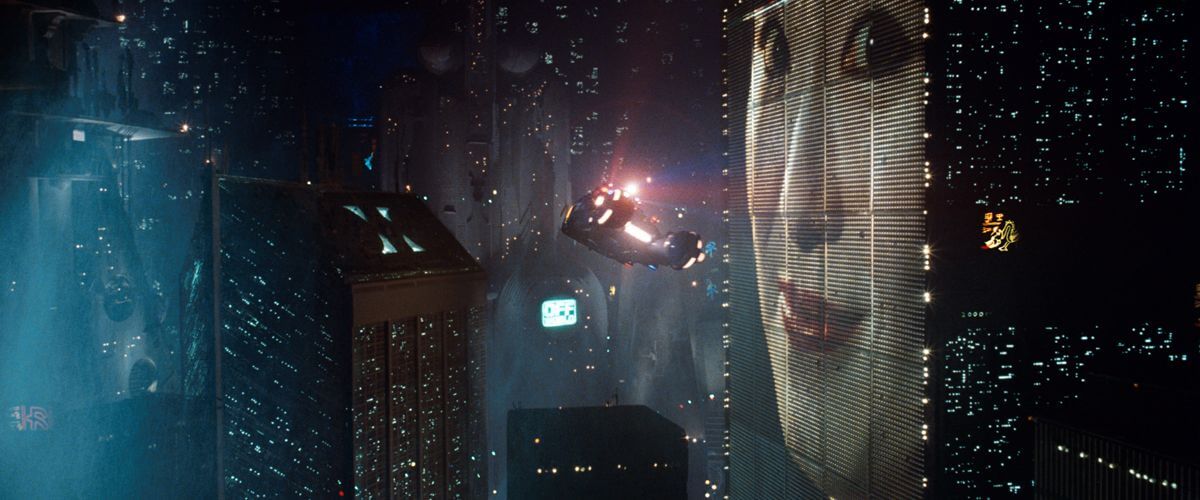

No matter how many years go by, Blade Runner continues to create a fully realized world that voyages beyond cinematic escapism and into the realm of prophetic futurism, described with breathtakingly real visuals to pose crucial questions about the limits of humanity and perception. Adapted by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples, the screen story follows the novel insofar that it prophesies such 21st century dilemmas as mass globalization, global warming, and genetic engineering; and though Scott’s sweeping, moody, dark visuals and bravado special FX capture the essence of Dick’s novel, the screenplay diverts from the author’s plot. But much of Dick’s grim future is used as a blueprint for the setting: Skies are blackened, as according to Dick’s novel, they are shrouded with nuclear fallout and dust; inconceivably large buildings and spires of industrialization reach to the tattered atmosphere; flying vehicles glide about the heights of a Los Angeles skyline that looks more like a New York City mutation in its vertical reach. Because of such environmental concerns, Earth has been abandoned for colonies in other parts of the galaxy, save for the human leftovers who keep the planet running. Those stragglers are derelicts living in empty buildings, abandoned from Earth’s virtual evacuation. Nature no longer exists, as humankind has wiped it out. Genetic engineering of animals is widespread, and in Dick’s book, to own an engineered animal is a sign of stature. Panning through blackened skies, the cityscape and worldview is neverendingly bleak.

Nevertheless, the film has been so elaborately conceived that everything from the costumes to the architecture still seem like components from a plausible dystopian future. The troubled world of Blade Runner, set in the Los Angeles of 2019, is expertly conceived by Dick and realized by Scott, and shows an oppressive weight on nature and humanity. A violent air of congestion transforms the complex cityscape into an almost irrational space. There is always a police presence, a monitoring airship, scanners, advertisements, or sensors flashing. This world feels familiar, yet futuristic, as designers were inspired by highly modernized and foreign cities like the frantic, neon-laded designs of Tokyo and Hong Kong. The film’s urban culture has long since grown out of control and deteriorated. The quality of life is low, justifying the numerous mentions of the idealized off-world colonies advertised on a floating airship above the city. The urban planners have given up on simplifying or reducing their cityscape; the inhabitants’ only hope is to leave Earth. Society has destroyed itself, beaten itself down with technology and architecture gone wild. And so, Blade Runner, as a concept of futurism, remains almost precognitive, certainly plausible, and even far removed from fantasy, noting how truly obscured humanity becomes when so disproportionately mixed with technology. Such cityscapes have been prevalent in cinema since the dystopian elements of Metropolis (1927) and Things to Come (1936) first graced the screen. Their monumental and imposing environments of overcrowded urbanism are breeding grounds for human alienation and the realized dreams of technology turned into nightmares. Blade Runner takes the idea of a city’s capacity to alienate and pushes it further, offering a city virtually abandoned and left to a small general population, who now has “plenty of room” in a city that feels overcrowded nonetheless.

Nevertheless, the film has been so elaborately conceived that everything from the costumes to the architecture still seem like components from a plausible dystopian future. The troubled world of Blade Runner, set in the Los Angeles of 2019, is expertly conceived by Dick and realized by Scott, and shows an oppressive weight on nature and humanity. A violent air of congestion transforms the complex cityscape into an almost irrational space. There is always a police presence, a monitoring airship, scanners, advertisements, or sensors flashing. This world feels familiar, yet futuristic, as designers were inspired by highly modernized and foreign cities like the frantic, neon-laded designs of Tokyo and Hong Kong. The film’s urban culture has long since grown out of control and deteriorated. The quality of life is low, justifying the numerous mentions of the idealized off-world colonies advertised on a floating airship above the city. The urban planners have given up on simplifying or reducing their cityscape; the inhabitants’ only hope is to leave Earth. Society has destroyed itself, beaten itself down with technology and architecture gone wild. And so, Blade Runner, as a concept of futurism, remains almost precognitive, certainly plausible, and even far removed from fantasy, noting how truly obscured humanity becomes when so disproportionately mixed with technology. Such cityscapes have been prevalent in cinema since the dystopian elements of Metropolis (1927) and Things to Come (1936) first graced the screen. Their monumental and imposing environments of overcrowded urbanism are breeding grounds for human alienation and the realized dreams of technology turned into nightmares. Blade Runner takes the idea of a city’s capacity to alienate and pushes it further, offering a city virtually abandoned and left to a small general population, who now has “plenty of room” in a city that feels overcrowded nonetheless.

The film tells the story of Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a former elite bounty hunter known as a blade runner, whose job it is to hunt Replicants: genetically engineered human beings created for off-world colonization and labor. When four rogue Nexus-6 brand Replicants return to Earth hoping to extend their limited life spans, Deckard is hired to find and retire (kill) them. Leader Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and Pris (Daryl Hannah) are two of Deckard’s targets, and both take refuge with chickenhead engineer J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson), who holds ties with their maker, Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel). The violent Leon (Brion James) and exotic dancer Zhora (Joanna Cassidy) are the other two, but they remain submerged somewhere in Dick’s vast, crumbling vision of the future’s Los Angeles. As a protagonist, Deckard’s laconic behavior and remoteness are symptoms of a man in an existential crisis. He has given up retiring Replicants; when he comes face-to-face with them, he reacts quickly and violently, being versed in the danger they pose. Under the surface, he fears what they represent and the ways they force him to question the nature of humanity. Perhaps he’s so reluctant to continue retiring Replicants because he no longer sees them as artificial. At the same time, we must question why Deckard, a skilled and outwardly composed professional, remains on the squalid Earth along with the diseased, derelict, and debauched populace who didn’t qualify for the off-world colonies. What is it that keeps him here? In contrast to Deckard are the lively Replicants who savor their brief lifespan; they play, seduce, kill, flirt, torment, laugh, and demonstrate an overall lust for life. Nevertheless, duty bound, Deckard systematically investigates and tracks down each Replicant until they are all gone, by either executing them on-site or, in the case of their leader Roy, watching as Roy dies when his expiration date comes due.

Replicants are unidentifiable by sight, engineered by Tyrell Corporation to be perfect examples of humanity—only smarter, stronger, and faster than the normal human. Their lives are restricted, however, to a period of a few years. As Tyrell explains, “The light that burns twice as bright burns half as long.” Dick often used examples of engineered beings as philosophical tools, to consider the limitations of what it means to be “human”. His novel We Can Build You tells of an automaton salesman who helps manufacture artificial copies of historical figures; and in the book, an Abraham Lincoln simulacrum, which develops a consciousness, decides, as Lincoln would, that he does not want to be sold. It is determined that consciousness denotes humanity, or at the very least, life. Thus, even what has been created by humans is not artificial. Roy and the other Nexus-6 Replicants rebel against their intended purpose because the bliss of consciousness consumes them; they fight to extend it and are burdened with its limitation. Aside from the incomplete profiles on each of his four targets, Deckard’s sole outlet for spotting a Replicant is the Voight-Kampff empathy test. The exam includes a pseudo-lie detector for Replicants that works by posing questions of human empathy; it reads involuntary flushes in the skin or pupil dilation, which would suggest naturally occurring physiological and emotional responses about or toward human and animal life—and a Replicant’s results will vary from that of a human. The Voight-Kampff empathy test supplies a counterargument for the Nexus-6 group’s claims on existence, through the emphasis of their incomplete human physiological and emotional imitation. Ironically, when Deckard identifies a rogue Replicant, he has been tasked with killing it and doing so without empathy, destabilizing the notion that feelings denote humanity.

Replicants are unidentifiable by sight, engineered by Tyrell Corporation to be perfect examples of humanity—only smarter, stronger, and faster than the normal human. Their lives are restricted, however, to a period of a few years. As Tyrell explains, “The light that burns twice as bright burns half as long.” Dick often used examples of engineered beings as philosophical tools, to consider the limitations of what it means to be “human”. His novel We Can Build You tells of an automaton salesman who helps manufacture artificial copies of historical figures; and in the book, an Abraham Lincoln simulacrum, which develops a consciousness, decides, as Lincoln would, that he does not want to be sold. It is determined that consciousness denotes humanity, or at the very least, life. Thus, even what has been created by humans is not artificial. Roy and the other Nexus-6 Replicants rebel against their intended purpose because the bliss of consciousness consumes them; they fight to extend it and are burdened with its limitation. Aside from the incomplete profiles on each of his four targets, Deckard’s sole outlet for spotting a Replicant is the Voight-Kampff empathy test. The exam includes a pseudo-lie detector for Replicants that works by posing questions of human empathy; it reads involuntary flushes in the skin or pupil dilation, which would suggest naturally occurring physiological and emotional responses about or toward human and animal life—and a Replicant’s results will vary from that of a human. The Voight-Kampff empathy test supplies a counterargument for the Nexus-6 group’s claims on existence, through the emphasis of their incomplete human physiological and emotional imitation. Ironically, when Deckard identifies a rogue Replicant, he has been tasked with killing it and doing so without empathy, destabilizing the notion that feelings denote humanity.

And yet, Tyrell adamantly insists on their advantages over humanity, their perfection—an engineered example of superior humanity. Roy even refers to himself, through poetry, as an angel; after all, the Tyrell Corporations’ maxim is “More Human Than Human.” In an ad-libbed recitation of William Blake’s poem America: A Prophesy, Roy says “Fiery the Angels fell, deep thunder rolled around their shores, burning with the fires of Orc.” Blake’s original lines were slightly different: “Fiery the Angels rose, and as they rose deep thunder roll’d, around their shores: indignant burning with the fires of Orc.” While Blake’s poem heralded themes of rebellion, Roy alters “rose” to “fell,” signifying the falling or death of Blake’s Angels, better suiting the terminal circumstances of the Nexus-6 Replicants. Roy identifies himself with god-like creatures, superior to man, but somehow lacking; angels are often considered to be greater than humans, and yet, they do not have humanity per se. In the spirit of Blake’s words, the Replicants do not rebel against an institution; rather, they rumble fatalistically against something they (as well as all of humanity) are hopeless to prevent: death. Because of this, Blade Runner presents a grand link between the artificial and the human. Replicants reach for life, whereas Deckard brings himself closer to death by killing those who so desire life. In metaphoric terms, humanity (Deckard) is rendered less than human for ostensibly killing itself; artificiality (the Nexus-6 Replicants) then becomes more than human for how it values life. Replicants are merely condensed versions of a traditional human, as if every bit of potential was filtered from an average person’s life and compiled into a personified form. By destroying that, Deckard, by extension, destroys himself.

Replicant consciousness is not suspect, but does their self-awareness denote humanity? Deckard’s relationship with Rachel (Sean Young), Tyrell’s assistant, sheds light on that question, as our hero’s romantic sympathies reside within her. While investigating the Tyrell Corporation, Deckard, who remains a devout noir protagonist, cold and straightforward, is asked to administer the Voight-Kampff exam on a non-engineered human, Rachel. When giving her the test, he barely discovers Rachel is in fact a Replicant. She exists with implanted memories and emotions, allowing for consciousness and a realized personality, which work to fool even the Replicant herself. For her own sake, Tyrell has engineered Rachel to be unaware of her construction. Blade Runner asks, What is humanity? Does it reside in self-preservation, self-awareness, memories, or dreams? Rachel contains all of these characteristics, and yet she is not human. As Dick’s novel states: “The electric things have their life too. Paltry as those lives are.” When Rachel begins to suspect what she is, she confronts Deckard, “Have you ever taken that test yourself?” and for the first time in Blade Runner openly brings into question Deckard’s humanity. It’s no coincidence that, when confronted by Rachel, Deckard’s eyes glow red in a reflection of light, just as Rachel’s and the artificial owl in Tyrell’s office do. This common science-fiction concept of a human protagonist discovering they are, in fact, not human, was widely explored by Dick in his short stories and novels, specifically the story “Impostor” (1953) and with sustained ambiguity in the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. In film, the concept was colorfully explored in writer-director Wesley Barry’s drive-in lark called The Creation of the Humanoids in 1962, wherein a scientist creates artificial “humanoids” that can reproduce, and the protagonist leader of a resistance movement against humanoids turns out to be an earlier model humanoid too. In the end, the other humanoids upgrade him into a reproducing model, and the operating doctor tells the audience: “Of course the operation was a success… Or you wouldn’t be here.” The Creation of the Humanoids also tells us “Mankind is a state of mind. Man is no more or less than he thinks himself to be.”

Replicant consciousness is not suspect, but does their self-awareness denote humanity? Deckard’s relationship with Rachel (Sean Young), Tyrell’s assistant, sheds light on that question, as our hero’s romantic sympathies reside within her. While investigating the Tyrell Corporation, Deckard, who remains a devout noir protagonist, cold and straightforward, is asked to administer the Voight-Kampff exam on a non-engineered human, Rachel. When giving her the test, he barely discovers Rachel is in fact a Replicant. She exists with implanted memories and emotions, allowing for consciousness and a realized personality, which work to fool even the Replicant herself. For her own sake, Tyrell has engineered Rachel to be unaware of her construction. Blade Runner asks, What is humanity? Does it reside in self-preservation, self-awareness, memories, or dreams? Rachel contains all of these characteristics, and yet she is not human. As Dick’s novel states: “The electric things have their life too. Paltry as those lives are.” When Rachel begins to suspect what she is, she confronts Deckard, “Have you ever taken that test yourself?” and for the first time in Blade Runner openly brings into question Deckard’s humanity. It’s no coincidence that, when confronted by Rachel, Deckard’s eyes glow red in a reflection of light, just as Rachel’s and the artificial owl in Tyrell’s office do. This common science-fiction concept of a human protagonist discovering they are, in fact, not human, was widely explored by Dick in his short stories and novels, specifically the story “Impostor” (1953) and with sustained ambiguity in the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. In film, the concept was colorfully explored in writer-director Wesley Barry’s drive-in lark called The Creation of the Humanoids in 1962, wherein a scientist creates artificial “humanoids” that can reproduce, and the protagonist leader of a resistance movement against humanoids turns out to be an earlier model humanoid too. In the end, the other humanoids upgrade him into a reproducing model, and the operating doctor tells the audience: “Of course the operation was a success… Or you wouldn’t be here.” The Creation of the Humanoids also tells us “Mankind is a state of mind. Man is no more or less than he thinks himself to be.”

In Blade Runner, Scott intentionally creates a world whose inhabitants are mere specks of human existence, whose world has dragged them down into desperate, pathetic lives that barely resemble humanity and, therein, this world becomes the perfect environment to explore the distinctions between human and Replicant. As a reluctant, difficult romance blooms between Deckard and Rachel, the blade runner begins to question even himself. Strange dreams float in his unconscious mind: a unicorn prances through an idyllic and softly lit forest, ethereal music plays, and the camera pans over archaic photographs to which Deckard has seemingly no association. Humanity has become an obscured ideal through Deckard’s example, especially with the realization that it can be mimicked, if not perfected by genetic engineering and implanted memories. Tyrell’s motto “More Human Than Human” begs the question: What makes us human if not memories and experiences? If humans can be engineered and made better than someone born naturally, and if they share similar emotions and a yearning to live, does that not earn them entrance into humanity? And if so, wouldn’t that make Deckard’s role as a blade runner paradoxical? If he’s killing Replicants who are thus more human, does that make him a murderer, as opposed to a police-backed bounty hunter? Edward James Olmos plays an officer named Gaff; no doubt left on Earth for his limp, he serves as a mysterious in-between for Deckard and his chief, Bryant (M. Emmet Walsh). Gaff places bits of origami at Replicant sites throughout the film, as though they should have meaning. And perhaps they do, looking at the way Deckard explores these pieces. Perhaps they recall some thought or memory in him, making the paper figure or animal curiously suspect. Not until the film’s final scene, when Deckard sees Gaff has placed an origami unicorn outside of his apartment door, does Deckard grasp a possible truth: that with his unicorn dreams known to Gaff, they could be implanted, and if so, Deckard may be a Replicant himself. Strangely, this insight, in no way absolute or confirmed by events in the film, was not always so in the long history of Blade Runner‘s production.

The first draft of the screenplay by Hampton Fancher, called Androids, based on Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, was optioned by actor-turned-producer Brian Kelly. Fancher and Kelly approached producer Michael Deeley to shop the screenplay around Hollywood, and Deeley eventually brought it to Ridley Scott. Fresh off the artistic and commercial successes of The Duellists (1977) and Alien (1979), Scott had begun his career as a set designer for the BBC and an imaginative commercial director responsible for hundreds of ads. The director initially turned Deeley’s offer down, as he was in negotiations to helm an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune for Dino de Laurentiis. But Scott’s eldest brother had just died of skin cancer, and the film’s probing inquiries on the legitimacy of life’s experiences, compounded by the saturated air of dourness, seemed more appropriate. His desperate attempts to distract himself from his pain would leave him immersed in layering the film with its signature detail, obsessively so. Once he signed to direct, Scott hired designer Syd Mead (Star Trek: The Motion Picture, TRON) to design the film’s vehicles, but Mead’s sketches proved so comprehensive that he was placed in charge of exteriors and interiors as well, under the title “visual futurist”. Mead conceived a retrofitted world in which architecture and machinery were developed by adding more onto them, as opposed to tearing down and building anew. Mead’s designs, informed by Scott’s own sketches and the director’s appreciation for the French comic Heavy Metal by Moebius, built the Los Angeles of the future by using photos of the Burbank Studios set of New York Street, erected in 1929 and the home of countless motion pictures since. Mead added huge ad monitors and wires, street signs and trafficators, neon lights and manhole steam, and an endless spree of mechanization throughout, all retrofitting the old town New York set into a dystopian world of incredible structures and realistic matte paintings. The crew named the eventual set “Ridleyville”, a nod to the full-scale city set-piece “Tativille”, built by French comedian Jacques Tati for PlayTime (1967).

The first draft of the screenplay by Hampton Fancher, called Androids, based on Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, was optioned by actor-turned-producer Brian Kelly. Fancher and Kelly approached producer Michael Deeley to shop the screenplay around Hollywood, and Deeley eventually brought it to Ridley Scott. Fresh off the artistic and commercial successes of The Duellists (1977) and Alien (1979), Scott had begun his career as a set designer for the BBC and an imaginative commercial director responsible for hundreds of ads. The director initially turned Deeley’s offer down, as he was in negotiations to helm an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune for Dino de Laurentiis. But Scott’s eldest brother had just died of skin cancer, and the film’s probing inquiries on the legitimacy of life’s experiences, compounded by the saturated air of dourness, seemed more appropriate. His desperate attempts to distract himself from his pain would leave him immersed in layering the film with its signature detail, obsessively so. Once he signed to direct, Scott hired designer Syd Mead (Star Trek: The Motion Picture, TRON) to design the film’s vehicles, but Mead’s sketches proved so comprehensive that he was placed in charge of exteriors and interiors as well, under the title “visual futurist”. Mead conceived a retrofitted world in which architecture and machinery were developed by adding more onto them, as opposed to tearing down and building anew. Mead’s designs, informed by Scott’s own sketches and the director’s appreciation for the French comic Heavy Metal by Moebius, built the Los Angeles of the future by using photos of the Burbank Studios set of New York Street, erected in 1929 and the home of countless motion pictures since. Mead added huge ad monitors and wires, street signs and trafficators, neon lights and manhole steam, and an endless spree of mechanization throughout, all retrofitting the old town New York set into a dystopian world of incredible structures and realistic matte paintings. The crew named the eventual set “Ridleyville”, a nod to the full-scale city set-piece “Tativille”, built by French comedian Jacques Tati for PlayTime (1967).

Co-produced and financed by three production companies through Warner Bros.—The Ladd Company for U.S. distribution, and Sir Run Run Shaw and Tandem Productions overseas—Blade Runner began filming on March 9, 1981, with a budget of $21.5 million, later raised to $28 million. The author remained somewhere in the back row during production, despite Blade Runner representing his body of work’s first filmic treatment. Getting his hands on Fancher’s script made matters worse for Dick, as he protested that the script’s tone was wrong. Scott then hired David Peoples to rewrite Fancher’s script to explore the enveloping world of the film further and emphasize a mystery “toward the spirit of Chinatown” to reflect the film’s bleak world. Fancher and Peoples would continue to make revisions throughout the two-year development and production. After reading an altered version, Dick congratulated Peoples with surprising enthusiasm, claiming his book and the screenplay would now compliment rather than detract from one another. But Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? seemed hardly a bankable title. Furthermore, Scott wanted to avoid calling Deckard a bounty hunter, as it seemed to criminalize the character through association, thus dehumanize his targets, which were originally called androids. It was all too common for Scott. Peoples’ microbiologist daughter suggest a variant of the world “replication” for the androids, and thus Replicant was born. Producers discovered William S. Burroughs’ script for Alan E. Nourse’s book The Bladerunner, a novel about black-marketing medical supplies, and purchased title rights. Fancher retitled Deckard’s job, which now made Deckard out as a harbinger of death, thus giving the production a more commercial title: Blade Runner.

Scott’s emphasis on visuality, so fantastically explored by Mead, was further enhanced by a special FX company called Entertainment Effects Group (EEG), partnered by Douglas Trumbull and Richard Yuricich. They had already made iconic effects on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and for Blade Runner they would once again create images at which the film’s characters would stand in awe. Trumbull himself participated in the effects work and, even after he left production to direct his own film for MGM (Brainstorm, 1983), he supervised to ensure his usual methods—such as shooting the effects on 65mm film stock for enhanced resolution, and then reducing them to the 35mm negative—were employed. Trumbull also supervised the use of computerized cameras that controlled motion over the elaborate miniatures used, since multiple pans over the miniatures were required to seamlessly integrate the sets, the flying cars called “spinners”, matte paintings, and the haze that gives the entire film that noirish look. Before production completed four months after it began, Scott invited the author for an on-set tour, where he was shown an extended special FX reel. Following his set visit, Dick wrote a letter to Jeff Walker of The Ladd Company to sing praises about the scenes he was shown, insisting that the filmmakers “may have created a unique form of graphic, artistic expression, never before seen. And, I think, Blade Runner is going to revolutionize our conceptions of what science-fiction is and, more, can be.” Even then, Dick could foresee, with the popularization and mass consumption of Blade Runner, science-fiction becoming more than yarns about robots and lasers. Could Blade Runner become prophecy contingent on society’s patterns of behavior, like a reflective device? Or at least precognitive for the sci-fi genre? Indeed, Dick’s readers found his material wading in the pool of intellectual entertainment; and his philosophical approach elevated his work to legendary status after his death, which, occurred from heart failure only a few months before Scott’s film hit theaters.

Scott’s emphasis on visuality, so fantastically explored by Mead, was further enhanced by a special FX company called Entertainment Effects Group (EEG), partnered by Douglas Trumbull and Richard Yuricich. They had already made iconic effects on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and for Blade Runner they would once again create images at which the film’s characters would stand in awe. Trumbull himself participated in the effects work and, even after he left production to direct his own film for MGM (Brainstorm, 1983), he supervised to ensure his usual methods—such as shooting the effects on 65mm film stock for enhanced resolution, and then reducing them to the 35mm negative—were employed. Trumbull also supervised the use of computerized cameras that controlled motion over the elaborate miniatures used, since multiple pans over the miniatures were required to seamlessly integrate the sets, the flying cars called “spinners”, matte paintings, and the haze that gives the entire film that noirish look. Before production completed four months after it began, Scott invited the author for an on-set tour, where he was shown an extended special FX reel. Following his set visit, Dick wrote a letter to Jeff Walker of The Ladd Company to sing praises about the scenes he was shown, insisting that the filmmakers “may have created a unique form of graphic, artistic expression, never before seen. And, I think, Blade Runner is going to revolutionize our conceptions of what science-fiction is and, more, can be.” Even then, Dick could foresee, with the popularization and mass consumption of Blade Runner, science-fiction becoming more than yarns about robots and lasers. Could Blade Runner become prophecy contingent on society’s patterns of behavior, like a reflective device? Or at least precognitive for the sci-fi genre? Indeed, Dick’s readers found his material wading in the pool of intellectual entertainment; and his philosophical approach elevated his work to legendary status after his death, which, occurred from heart failure only a few months before Scott’s film hit theaters.

One can only suspect that Dick would be more than pleased with Blade Runner’s eventual outcome, no matter which version he viewed, and over the years there would be many to choose from. In 1982, when the theatrical version of Scott’s finished film was released, the ending was wholly different compared to the one audiences know today. Instead of surviving Roy’s attack and escaping with Rachel only to realize that he too is a Replicant, Deckard escapes with Rachel in the Theatrical Cut, to a picturesque forest landscape (borrowed from outtakes of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, 1980). Moreover, Deckard’s unicorn dream sequence was left on the cutting room floor, and with it the final implication that Deckard is not human. The Theatrical Cut also mulls along with inglorious explanatory voiceover narration, which was added when co-producers at Tandem test-screened an early cut and received complaints about the narrative being “muddled”. Harrison Ford voiced his frustrations toward the Theatrical Cut, specifically about his character’s voiceover, telling Empire, “When we started shooting, it had been tacitly agreed that the version of the film that we had agreed upon was the version without voiceover narration. It was a fucking nightmare. I thought that the film had worked without the narration. But now I was stuck recreating that narration. And I was obliged to do the voiceovers for people that did not represent the director’s interests.” Some reports say Ford gave intentionally poor readings of his narration lines so that producers would opt not to use it. Alas, the narration found its way into the theatrical version anyway, despite being badly read and unnecessary to the narrative.

Critics responded almost unanimously, praising the film’s visual mastery but censuring its empty emotional core. Worse, Blade Runner opened just two weeks after Steven Spielberg’s E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, one of the most successful and crowd-pleasing box-office hits of all time, and Scott’s demanding film was quickly overshadowed. Audiences expecting the new standard of sci-fi adventure, established just a few years before with Star Wars (1977), reinforced with The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and anticipated on Return of the Jedi the coming year, met Blade Runner with disappointment over its lack of blockbuster fun and flair. The film opened to $6.1 million in receipts, and then went on to make about $14 million, just half of its budget. Still, with the popularity of science-fiction on home video and the film’s own demand for repeat viewings to process Scott’s layered approach, the film’s popularity grew. In 1990, while scouring through Blade Runner archives, film restorer Michael Arick found a Workprint Cut, which Scott had roughly edited as his intended Director’s Cut, but never finished. Back in 1982, the studio opted for the Theatrical Cut’s more commercial ending, so Scott’s alternate was buried. Now rediscovered, the Workprint was shown at some minor sold-out screenings and earned admiration for its diverse interpretation of the now cult-classic film. Warner Bros. then paid Arick and Blade Runner’s assistant editor Les Healey to work from Scott’s notes on his version, including changes in tone, reinsertion of the unicorn scene, removal of the voiceover, and most importantly the famous ending that suggests Deckard is indeed a Replicant.

Critics responded almost unanimously, praising the film’s visual mastery but censuring its empty emotional core. Worse, Blade Runner opened just two weeks after Steven Spielberg’s E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, one of the most successful and crowd-pleasing box-office hits of all time, and Scott’s demanding film was quickly overshadowed. Audiences expecting the new standard of sci-fi adventure, established just a few years before with Star Wars (1977), reinforced with The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and anticipated on Return of the Jedi the coming year, met Blade Runner with disappointment over its lack of blockbuster fun and flair. The film opened to $6.1 million in receipts, and then went on to make about $14 million, just half of its budget. Still, with the popularity of science-fiction on home video and the film’s own demand for repeat viewings to process Scott’s layered approach, the film’s popularity grew. In 1990, while scouring through Blade Runner archives, film restorer Michael Arick found a Workprint Cut, which Scott had roughly edited as his intended Director’s Cut, but never finished. Back in 1982, the studio opted for the Theatrical Cut’s more commercial ending, so Scott’s alternate was buried. Now rediscovered, the Workprint was shown at some minor sold-out screenings and earned admiration for its diverse interpretation of the now cult-classic film. Warner Bros. then paid Arick and Blade Runner’s assistant editor Les Healey to work from Scott’s notes on his version, including changes in tone, reinsertion of the unicorn scene, removal of the voiceover, and most importantly the famous ending that suggests Deckard is indeed a Replicant.

Warner Bros. released the Director’s Cut into theaters in September 1992, where it was hailed unanimously as a work far superior to its previous iteration, despite some obvious continuity and dubbing errors. At that point, Scott himself was strained with limited time to oversee and thoroughly apply his perfectionist’s touch to the Director’s Cut, as he was completing Thelma & Louise (1991) for MGM. Furthermore, Scott insisted to Warner Bros. that they provide a considerable sum to fix poor looping and exposed special FX apparatuses visible in the Theatrical Cut, but no such patchwork was made because, for the studio, putting more money into revamping a film that previously flopped was poor business, no matter how positive Workprint screenings were. Still, the Director’s Cut made an impact in its theatrical re-release, from its reinforced influence on cyberpunk stylization to the rediscovery of Philip K. Dick’s library. Not only were several of Dick’s novels and short story collections issued into republication around this time, but film properties that had long gestated were put into production after early screenings of the Workprint Cut were so enthusiastically received. After the new version of Blade Runner had circulated, Dick’s short stories “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (1966) and “Second Variety” (1953) were made into the films Total Recall (1990) and Screamers (1995) respectively. Dick’s story “The Minority Report” was optioned in 1992 as a sequel to Total Recall, but was eventually adapted into the tense and imaginative 2002 thriller Minority Report, directed by Steven Spielberg. Dick has subsequently become one of the most adapted book-to-film authors, next to Stephen King. Between 1992 and the early 2000s, the Director’s Cut of Blade Runner was hailed as visionary filmmaking and its status elevated from cult-classic to just a plain, simple classic. With its increasing popularity, Warner Bros. finally saw fit to allow Scott—who, now further established as a profitable filmmaker with titles like Gladiator (2000) and Black Hawk Down (2001) under his belt, remained unsatisfied with his so-called Director’s Cut—the time and money to improve his film one more time.

Working with longtime collaborator and restoration producer Charles de Lauzirika, Scott oversaw a remastered and improved cut from the original negatives, complete with audio, visual, and special FX cleanups to his specifications. In 2007, prints of Blade Runner: The Final Cut traveled among arthouse theaters, receiving rave reviews for Scott’s now perfected vision. To the naked eye, one might not notice changes from the Director’s Cut to Final Cut; the alterations are primarily a fine-toothed cleaning, fixing those minute details visible only to the trained eye or devout fans of the film. Among the inclusions are extended scenes from the Workprint Cut and International Cuts, namely a lengthened unicorn sequence and some bloodier violence that was trimmed from American cuts. In one scene, Roy crushes Tyrell’s head, pressing out his victim’s eyes in the process; blood now streams generously from his victim’s sockets. Later, we see Roy press a nail through his own hand to prolong his failing synthetic body; that scene has been elongated, now showing the nail popping out from the other side. In Zhora’s death sequence where she runs herself through plates of glass, the stuntwoman’s face was originally quite apparent; Scott reshot this scene with Joanna Cassidy, still looking as young as ever, to repair the visible inconsistency. The Director’s Cut also contained a scene with dialogue out of sync, the result of poor looping; Ford’s mouth has been digitally replaced, matching up what we hear with what we see, thanks to the participation of Ford’s son, Ben. With this Final Cut of Blade Runner, changes are less obvious than some other Ridley Scott Director’s Cuts. For Alien, Gladiator, and the underrated Kingdom of Heaven (2005, which included significant improvements after 45 minutes were reinserted into the film), Scott reincorporated, reedited, or sometimes removed whole scenes to create an alternate outlook. And while we might accuse another director for making such alterations solely for marketing purposes, given Blade Runner‘s complexity it’s no wonder he was drawn back to it again and again. As a young filmmaker, Scott may not have had the power his now esteemed reputation as a consistently successful filmmaker affords him; that power, now developed, permitted him to recut his work in a manner that lives up to his vision.

Working with longtime collaborator and restoration producer Charles de Lauzirika, Scott oversaw a remastered and improved cut from the original negatives, complete with audio, visual, and special FX cleanups to his specifications. In 2007, prints of Blade Runner: The Final Cut traveled among arthouse theaters, receiving rave reviews for Scott’s now perfected vision. To the naked eye, one might not notice changes from the Director’s Cut to Final Cut; the alterations are primarily a fine-toothed cleaning, fixing those minute details visible only to the trained eye or devout fans of the film. Among the inclusions are extended scenes from the Workprint Cut and International Cuts, namely a lengthened unicorn sequence and some bloodier violence that was trimmed from American cuts. In one scene, Roy crushes Tyrell’s head, pressing out his victim’s eyes in the process; blood now streams generously from his victim’s sockets. Later, we see Roy press a nail through his own hand to prolong his failing synthetic body; that scene has been elongated, now showing the nail popping out from the other side. In Zhora’s death sequence where she runs herself through plates of glass, the stuntwoman’s face was originally quite apparent; Scott reshot this scene with Joanna Cassidy, still looking as young as ever, to repair the visible inconsistency. The Director’s Cut also contained a scene with dialogue out of sync, the result of poor looping; Ford’s mouth has been digitally replaced, matching up what we hear with what we see, thanks to the participation of Ford’s son, Ben. With this Final Cut of Blade Runner, changes are less obvious than some other Ridley Scott Director’s Cuts. For Alien, Gladiator, and the underrated Kingdom of Heaven (2005, which included significant improvements after 45 minutes were reinserted into the film), Scott reincorporated, reedited, or sometimes removed whole scenes to create an alternate outlook. And while we might accuse another director for making such alterations solely for marketing purposes, given Blade Runner‘s complexity it’s no wonder he was drawn back to it again and again. As a young filmmaker, Scott may not have had the power his now esteemed reputation as a consistently successful filmmaker affords him; that power, now developed, permitted him to recut his work in a manner that lives up to his vision.

The Final Cut contains no obvious CGI inclusions—unlike, say, George Lucas’ subsequent versions of his original Star Wars films—nor bastardization of the film’s verisimilitude. Even today, more than thirty years later, Blade Runner‘s original, tactile effects outshine even the most impressive digital wizardry conceived by FX houses (which originated with another 1982 film, TRON). Take the completely convincing, abundant models and their mesmerizing presentation in Deckard’s panoramic spinner flights through the Los Angeles of the future. Motion-controlled cameras move through Mead’s various miniatures and pass by other flying cars, combining some 35 elements from buildings to vehicles to matte paintings. But the space onscreen is not the digital realm of Avatar (2009); rather, it’s a tangible environment, rendered by effects that create a believable futureworld for a film that, thematically, demands we question the veracity of what we see. As dystopian as the city proves, the viewer cannot help but explore this world with our eyes and see a place of horrible beauty. The city subsists as an entrancing landscape filled with unknowable detail, and seeds of a larger, ever-expanding universe are implanted, from mentions of off-world colonies to the mystery of Deckard’s identity to the brief shot from the interior of a spaceship traveling through the stars. Curiously, no imagery proves more strangely affecting, or more effective in awakening our mind’s eye, than Roy’s final worlds, which always tingle the imagination: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I’ve watched c-beams glitter in the dark near the Tanhauser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears… in the rain.” If Deckard’s flights through the city give a mesmerizing overview of the landscape, then Roy’s final speech closes the film’s overarching tour of the future with an acknowledgment that there’s more going on in the world of Blade Runner than the viewer can ever know or experience. Combined, the two scenes sum up the film’s cinematic experience in a succinct metaphor, whereby the film’s audience marvels at the fantastical visuality, and then is left in wonder about the intricacy of everything onscreen and the unresolved mystery hinted elsewhere.

Regardless of how visionary the world created in Blade Runner looks and feels, Scott admits that it’s a film “set forty years hence, made in the style of forty years ago,” and in that combination of styles the film bridges noir and cyberpunk influences. Film noirs of the 1940s and 1950s heavily influenced the film’s story structure. Deckard is a Philip Marlowe-type detective, the stuff of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. He scours the rain-swept streets of Los Angeles’ underbelly to expose questionable morality in the bemused leisure class, exposing what lingers in the shadows and, along the way, falls for the wrong dame, the omnipresent femme fatale. In film noir stories of this kind, such as The Asphalt Jungle (1950) or Night and the City (1950), the city is the figurative epicenter for the protagonist’s moral and pointedly existential crisis. And in Blade Runner, the crisis becomes a search to identify that which is human and artificial, the real and the perceived reality. This crisis also serves as a precursor to the emergence of the sci-fi subgenre cyberpunk, which takes place largely in cyberspace but also resides in the underground levels and looks up at the dominating technology above. Blade Runner emerged in the same year as films like TRON and Videodrome, both ground-breaking postmodern works that map a cyberspace environment as something to patrol or explore, which ultimately overwhelm their protagonists and drive them to escape in one form or another. These are worlds of neon colors and commercial architecture, all brought to life within an electronic cyber-verse that, in the case of Blade Runner, may all be artificially perceived by a Replicant. Author William Gibson finally solidified cyberpunk ideas from these films and has acknowledged their influence on his book Neuromancer (1984), the springboard of the cyberpunk subgenre.

Regardless of how visionary the world created in Blade Runner looks and feels, Scott admits that it’s a film “set forty years hence, made in the style of forty years ago,” and in that combination of styles the film bridges noir and cyberpunk influences. Film noirs of the 1940s and 1950s heavily influenced the film’s story structure. Deckard is a Philip Marlowe-type detective, the stuff of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. He scours the rain-swept streets of Los Angeles’ underbelly to expose questionable morality in the bemused leisure class, exposing what lingers in the shadows and, along the way, falls for the wrong dame, the omnipresent femme fatale. In film noir stories of this kind, such as The Asphalt Jungle (1950) or Night and the City (1950), the city is the figurative epicenter for the protagonist’s moral and pointedly existential crisis. And in Blade Runner, the crisis becomes a search to identify that which is human and artificial, the real and the perceived reality. This crisis also serves as a precursor to the emergence of the sci-fi subgenre cyberpunk, which takes place largely in cyberspace but also resides in the underground levels and looks up at the dominating technology above. Blade Runner emerged in the same year as films like TRON and Videodrome, both ground-breaking postmodern works that map a cyberspace environment as something to patrol or explore, which ultimately overwhelm their protagonists and drive them to escape in one form or another. These are worlds of neon colors and commercial architecture, all brought to life within an electronic cyber-verse that, in the case of Blade Runner, may all be artificially perceived by a Replicant. Author William Gibson finally solidified cyberpunk ideas from these films and has acknowledged their influence on his book Neuromancer (1984), the springboard of the cyberpunk subgenre.

With so much in Blade Runner concerning visuality, and the distance between humanity and artificiality, in many ways, the film is about perception, a theme that emerges in imagery related to the eyes and vision. Accordingly, the film requires active visual participants, willing subjects from whom much is demanded and, through careful observation and cognition of the film, form their perceptions about what has appeared onscreen. Scott called the film “a 700-layer cake” in which a “kaleidoscopic accumulation of detail” occupies the frame. Beyond the sheer multitude of details, eyes themselves play a major role. One of the first shots is a close-up of an open eye looking over the fiery spires of Los Angeles. At Eye Works, James Hong’s genetic engineer character makes eyes for the Tyrell Corporation and designed Roy’s eyes. The Voight-Kampff test scans the eye, while Deckard watches an enhanced video-screen image of the eye blown-up. Ironically, Tyrell wears thick-lens glasses and without them would undoubtedly be blind; his eyes are gouged out by Roy. The examples go on and on. And contrary to the axiom “it must be seen to be believed”, nothing seen in Blade Runner represents truth. Illusion and misread meanings are everywhere: artificial humans and animals, memory implants, forged photographs, false dreams, and a young scientist who looks old. In a brief yet lingering moment, Deckard looks at a photograph of Rachel as a child beside her mother, and the image in the photo comes to life in his hand. Is this some futuristic version of photographs that come alive when someone picks them up? Or did Deckard’s perspective project life onto the photo? Or perhaps the photo was a memory implanted in both he and Rachel’s heads? A photograph, which is so often considered a tangible proof of one’s history, becomes something intangible here, such as when Deckard scans a photo on a computer device that reveals its layers and hidden truths.

Philip K. Dick’s frequent exploration of perceived realities that begin to breakdown upon inspection, and thus define the fragile, shattered nature of existence and humanity, is brought to awe-inspiring life through Blade Runner. Ridley Scott made a film whose influence, intellectual scope, and visual power challenge the greatest science-fiction tales from Metropolis to Minority Report. And behind Scott’s rich layering of the film’s striking imagery resides an idea, countless ideas in fact, which linger in the viewer’s mind long after the film has ended, perpetuating its legacy and sustaining its existential mystery. Dick’s transcendent themes have never achieved such a glorious marriage of production and narrative sophistication. The question of the film is one of identity, and against the unending and mechanized city, a person, human or otherwise, faces isolation, and must resolve whether they are part of the landscape or independent of it, whether their world is real or perceived. But then, nothing is for certain in Blade Runner, neither memory nor sight, and certainly not identity. Both the film’s characters and its meaning question the reality of everything, and by its fateful conclusion demands that we rely on our perceptions to create the world around us. Here, the elaborate urban future imagined by Dick and realized by Scott reflects Deckard’s state as a Replicant; the metropolis is an extended metaphor for humanity retrofitted and built upon until it becomes natural and unnatural, something both beautiful and horrifying to perceive.

Philip K. Dick’s frequent exploration of perceived realities that begin to breakdown upon inspection, and thus define the fragile, shattered nature of existence and humanity, is brought to awe-inspiring life through Blade Runner. Ridley Scott made a film whose influence, intellectual scope, and visual power challenge the greatest science-fiction tales from Metropolis to Minority Report. And behind Scott’s rich layering of the film’s striking imagery resides an idea, countless ideas in fact, which linger in the viewer’s mind long after the film has ended, perpetuating its legacy and sustaining its existential mystery. Dick’s transcendent themes have never achieved such a glorious marriage of production and narrative sophistication. The question of the film is one of identity, and against the unending and mechanized city, a person, human or otherwise, faces isolation, and must resolve whether they are part of the landscape or independent of it, whether their world is real or perceived. But then, nothing is for certain in Blade Runner, neither memory nor sight, and certainly not identity. Both the film’s characters and its meaning question the reality of everything, and by its fateful conclusion demands that we rely on our perceptions to create the world around us. Here, the elaborate urban future imagined by Dick and realized by Scott reflects Deckard’s state as a Replicant; the metropolis is an extended metaphor for humanity retrofitted and built upon until it becomes natural and unnatural, something both beautiful and horrifying to perceive.

Bibliography:

Bakatman, Scott. Blade Runner. (BFI Film Classics). 2nd Edition. British Film Institute, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review