The Definitives

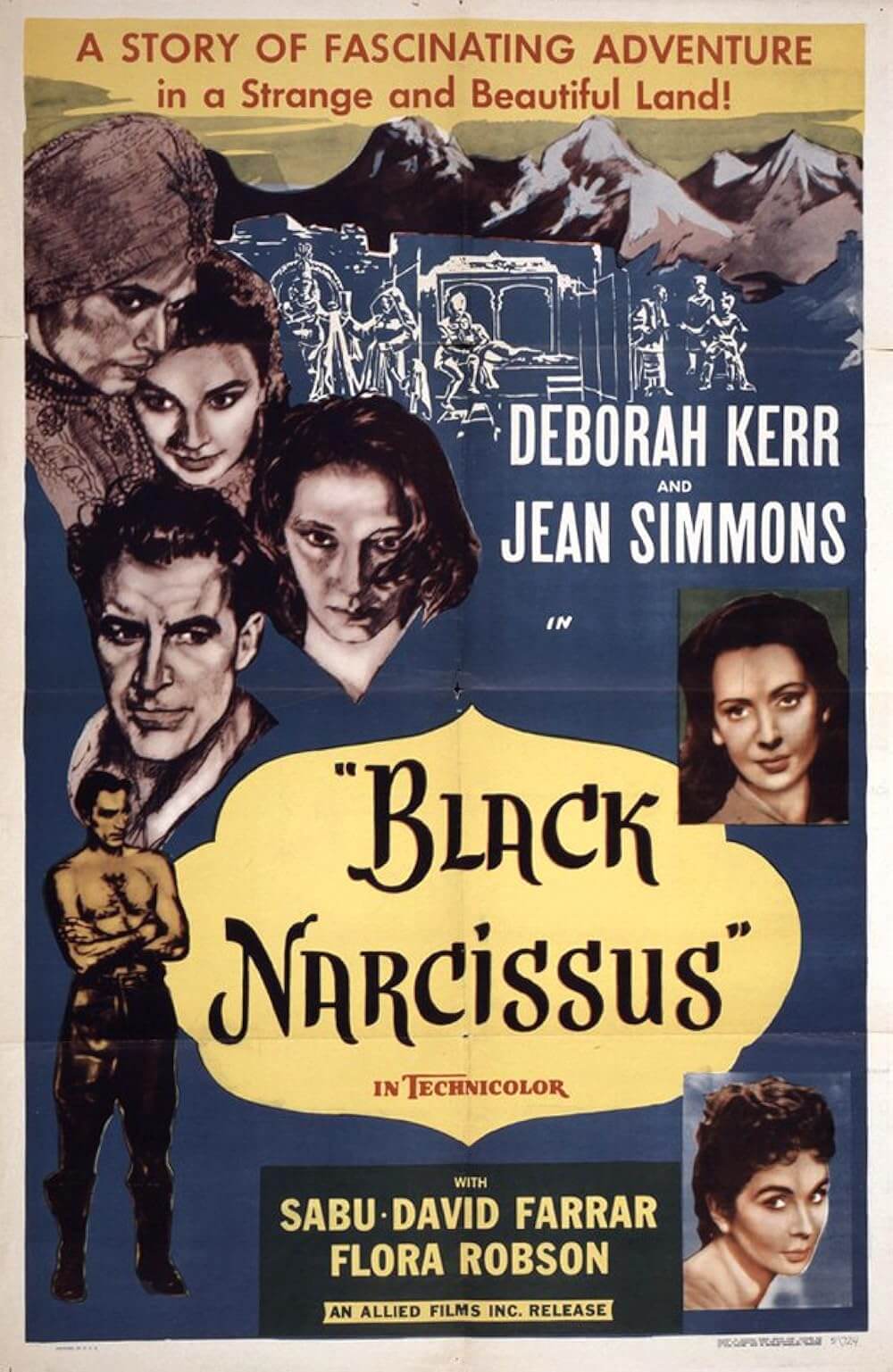

Black Narcissus (1947)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Michael Powell created a symphony of image, sound, and symbolism in Black Narcissus to establish a harmony between his aesthetics and Emeric Pressburger’s script. The British duo known as The Archers framed their 1947 picture, about missionary nuns in a cliffside palace in the Himalayan region of North India, against the decline of the British Empire throughout the world. The title alone, a dual reference to the Greek myth about vanity and the film’s cheap, but no less intoxicating perfume, signals the conceit of British imperialism, domesticity, and characteristic self-denial in the face of rapturous desire. In its contrast between asceticism and uninhibited sexuality, the film is an exploration of these contemporary British concerns through characters who attempt to maintain control over their worlds, and themselves, whether those worlds exist under imperialist rule, religious doctrine, or social order. Black Narcissus is about the return of the repressed, awakened by the failure of systems that attempt to retain some measure of control over the body and spirit. These systems will inevitably fail, even as they reinforce, curiously, the beliefs of the film’s Sister Clodagh, a brooding character who inwardly questions her vocation. In a film ripe with thematic contrasts, Powell and Pressburger search for a place between the extremes of chastity and pruriency.

Black Narcissus marks the first time The Archers used material other than their own. Their mostly faithful adaptation was based on the novel by Rumer Godden, whose The River would be made into a splendid film in 1951 by Jean Renoir and become the first Technicolor picture shot entirely in India. However, The Archers made their film almost entirely on soundstages, a world enclosed unto itself to capture the story’s inherent melodrama with embellished cinematic expression. “There’s something in the air that makes everything exaggerated,” warns Mr. Dean (David Farrar), the nun’s British contact who is stationed in the village. Although he’s referring to the location of the palace, a former harem repurposed into a home for celibate nuns, the remark describes the entire film—a site on which oppositional ideologies clash. The emotions and visual symbolism of Black Narcissus have been amplified to stress its themes and conflicts, which extend from the suppression of natural impulses to what scholar Ian Christie called a “spiritual preparation for the British withdrawal from India.” While Godden’s treatment of these concerns reveals her interest in Orientalist worldviews, Powell and Pressburger consider the larger implications in a theme they would return to again, above all in Gone to Earth (1950)—that social, imperialist, and religious control will destroy purity and beauty.

Closely following the plot of Godden’s novel, the story focuses on a group of Calcutta (now Kolkata) nuns who travel to the Himalayas, intent on opening a school for children, a dispensary, and a class for girls at an old palace called Mopu, once known as a “House of Women.” Given to them by a local General (Esmond Knight), Mopu rests on the edge of a remote mountain cliff, where the wind never rests and the palace’s history weighs heavily on the nuns. It’s “no place to put a nunnery,” warns Mr. Dean. Mopu still features erotic paintings, and the grounds are tended by Angu Ayah (May Hallett), an old woman who prefers the palace’s “fun” old days of lubriciousness. While the nuns attempt to bring education and healthcare, not to mention their religion, to the region, they struggle to convert Kanchi (Jean Simmons), a local girl who flirts with Dilip Rai (Sabu), the General’s nephew. Headed by Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), the Order of the Servants of Mary face challenges in their ranks as well. Clodagh, still reeling from a failed romance that left her escaping to religion, despises Mr. Dean’s cynicism and disapproval of their Order. But they form a mutual respect, even an unspoken attraction. Meanwhile, a younger and troubled nun, Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), becomes enthralled with the area, and with Mr. Dean, only to be rejected. In a state of deep sexual resentment, she lashes out at Sister Clodagh, trying to kill her, but Sister Ruth falls to her death over the cliffside. Her death signals that the nuns have failed at Mopu, and they return to Calcutta.

Closely following the plot of Godden’s novel, the story focuses on a group of Calcutta (now Kolkata) nuns who travel to the Himalayas, intent on opening a school for children, a dispensary, and a class for girls at an old palace called Mopu, once known as a “House of Women.” Given to them by a local General (Esmond Knight), Mopu rests on the edge of a remote mountain cliff, where the wind never rests and the palace’s history weighs heavily on the nuns. It’s “no place to put a nunnery,” warns Mr. Dean. Mopu still features erotic paintings, and the grounds are tended by Angu Ayah (May Hallett), an old woman who prefers the palace’s “fun” old days of lubriciousness. While the nuns attempt to bring education and healthcare, not to mention their religion, to the region, they struggle to convert Kanchi (Jean Simmons), a local girl who flirts with Dilip Rai (Sabu), the General’s nephew. Headed by Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), the Order of the Servants of Mary face challenges in their ranks as well. Clodagh, still reeling from a failed romance that left her escaping to religion, despises Mr. Dean’s cynicism and disapproval of their Order. But they form a mutual respect, even an unspoken attraction. Meanwhile, a younger and troubled nun, Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), becomes enthralled with the area, and with Mr. Dean, only to be rejected. In a state of deep sexual resentment, she lashes out at Sister Clodagh, trying to kill her, but Sister Ruth falls to her death over the cliffside. Her death signals that the nuns have failed at Mopu, and they return to Calcutta.

Black Narcissus echoes the failure of British imperialism in India, which started in the eighteenth century. In the 1770s, the British East India Company began to take control of Bengal by installing a puppet leader. Eight decades later, the British had almost entirely subjugated the country through several wars, annexations, and manipulative negotiations and treaties. After the violent Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, which found Indian soldiers rebelling against British officers in a series of escalating attacks, the British government resolved to take over the region from their East India Company in the 1858 Government of India Act. But the next six decades of imperialism would find the British Empire struggling to maintain control over the country, as the local population rallied for nationalistic initiatives and, eventually, independence. A series of concessions made by the colonizers soon led to reforms and increased voting rights for Indians, diminishing the British rule and inciting an anti-colonialist call for freedom after the First World War, as Mahatma Gandhi organized passive resistance campaigns. Throughout the 1930s, the British government continued to make promises that India could self-govern, but they remained in power, and protests continued. After World War II, the demand for independence accelerated until, finally, the British signed the Indian Independence Bill on August 15, 1947, dissolving the world’s largest empire.

Black Narcissus was released in the United Kingdom on May 4, 1947, just two months before British Imperialism reached this turning point. Although Godden’s book was published years earlier, Powell and Pressburger’s film addresses the fragility of their country’s control over India. The Sisters represent agents of British imperialism in their missionary work; the Order hopes to convert Mopu into a place of worship and the locals to their Western, Christian ideology. But their presence in the territory proves fragile, indicated by the tentative nature of their own vows. The Order requires its members to renew their vows each year, which Mother Dorothea (Nancy Roberts) considers their “greatest strength,” though it also becomes their greatest weakness. The need to reinforce their beliefs and question loyalty annually underscores their uncertainty, raising constant doubts. Aware that Mopu could accelerate those doubts, Mother Dorothea tells Clodagh to “work them hard” to keep the Order distracted and their minds off the surrounding temptations, the inherent isolation, and the delicacy of their colonial station. The locals, too, present frequent challenges for the nuns, such as how Dilip Rai gives in to his temptation with Kanchi, or how the villagers hold the entire Order responsible for the unpreventable death of a child. In each case, the conflicts raise awareness about the insecure and uneasy relationship between the colonizer and the colonized, which undermines any hope of stability, thus exposing the fragility of imperialism. However, it’s not only their own vows that weaken them, but their inability to view the locals outside the context of racial difference.

Before they arrive, a letter from Mr. Dean introduces Clodagh to the area. His letter, heard in voiceover, attempts to establish Mopu and the surrounding area with almost travelogue descriptions. “The people are like mountain peasants everywhere, simple, independent,” his voice observes. “They smile when they feel like it. They work because they must.” It is a Western voice making observations with almost anthropological detachment and superiority, yet also an acceptance that the nuns will not share. “The men are men, no better and no worse than anywhere else. The women are women. The children, children.” If Dean’s view seeks almost scientific objectivity, the Order takes an imperialist and Orientalist view when they note how Dean has “gone native.” That the nuns view his willingness to integrate and conform to local customs, and not hold himself superior to Indian ways, anticipates their own failure in the region. They spend their time trying to ignore the open space, wind, and Otherness, which requires tireless work just to keep their minds from wandering—and even then, it doesn’t stop Clodagh from recalling her romance in Ireland (her lips redden and cheeks blush at the thought of Ireland). It’s a “disturbing” and “distracting” atmosphere. It also emphasizes their own immersion in a worldview rooted in the Saïdian Oriental—a critical theory about Western perspective on the East, explored by postcolonial scholar Edward Saïd, that identifies how Western imperialist power creates a series of negative stereotypes and false associations about peoples in India and the Middle East.

Before they arrive, a letter from Mr. Dean introduces Clodagh to the area. His letter, heard in voiceover, attempts to establish Mopu and the surrounding area with almost travelogue descriptions. “The people are like mountain peasants everywhere, simple, independent,” his voice observes. “They smile when they feel like it. They work because they must.” It is a Western voice making observations with almost anthropological detachment and superiority, yet also an acceptance that the nuns will not share. “The men are men, no better and no worse than anywhere else. The women are women. The children, children.” If Dean’s view seeks almost scientific objectivity, the Order takes an imperialist and Orientalist view when they note how Dean has “gone native.” That the nuns view his willingness to integrate and conform to local customs, and not hold himself superior to Indian ways, anticipates their own failure in the region. They spend their time trying to ignore the open space, wind, and Otherness, which requires tireless work just to keep their minds from wandering—and even then, it doesn’t stop Clodagh from recalling her romance in Ireland (her lips redden and cheeks blush at the thought of Ireland). It’s a “disturbing” and “distracting” atmosphere. It also emphasizes their own immersion in a worldview rooted in the Saïdian Oriental—a critical theory about Western perspective on the East, explored by postcolonial scholar Edward Saïd, that identifies how Western imperialist power creates a series of negative stereotypes and false associations about peoples in India and the Middle East.

The threat of Orientalized sexuality in the East propels Black Narcissus, a film that earns its title from the intoxicating scent worn by Dilip Rai, which summons the exotic, something the nuns in all their Western and Christian piety struggle to understand or accept. Although Dilip Rai’s scent was purchased in an “Army and Navy” shop in London, it nonetheless reflects the uninhibited nature of the sensuous, desirous body, a trait the British nuns associate with Orientalized spaces of India. Mopu contains the “unbounded sexuality” that Saïd associates with Orientalist perspectives, evidenced in its murals and the stirred-up desires between Dilip Rai and Kanchi, as well as Ruth and Mr. Dean. Whereas the Western nuns behave reserved and orderly, their Indian counterparts burst with what Saïd called “libertine and less guilt-ridden” ideas about sex, though these associations stem from a worldview that sees Indians as uncivilized peasants. Sister Ruth, the most susceptible to her sexual desires and prejudices, holds pronounced and derisive feelings about the locals, who she calls “very stupid” and admits “they all look alike to me.” She feels the “primitive people” should be dealt with like “primitive children.” Her sharp feelings about the Indian locals remain at odds with how the Orientalized atmosphere infects her—a lust for Mr. Dean that ultimately leads to Ruth refusing to renew her vows and attacking Clodagh out of jealousy. Ruth’s choice represents how firmly the nuns have been ingrained into their Orientalist perspective. Their continued belief in Mopu’s intangible, corrupting power leads to the failure of their mission. To a greater extent, their failure reveals how imperialist ideals cannot last and anticipates the end of British rule in India.

Arriving in the wake of World War II, Black Narcissus confronted the British Empire’s instability as a former world power, which was now shaken to its core by two world wars and nationalist movements in their Asian and African colonies, weakening their control. Within a few decades, most former British colonies would become independent countries, free from an official colonizing power, although still subject to cultural colonization. During this period, the British struggled to acclimate and build up their infrastructure at home. The British were suffering from a crisis of national identity, not only because their empire had declined but because poverty and economic instability had rocked the country in the postwar years. Rationing initiatives, active since the war, continued to ensure that everyone received access to the bare necessities. Nevertheless, consumer goods remained in short supply, fostering a black market. In this environment, the individual suffered in favor of a larger, selfless nationalism. Scholar Andrew Moor observes, “The recruitment of the people as a fighting force brought them into a public arena, figuratively eradicating private spaces and individual interests.” British women experienced the most dramatic changes throughout this period.

Gender roles had shifted during the war, and again afterwards, much as they had in the United States. Women who worked full-time jobs in the war years were expected to return to their previous domestic roles. Birth rates were down, juvenile crime was up, and women who had been liberated by joining the workforce were blamed for these trends. The Royal Commission on Population reported that family stability depended upon women being in domestic roles, even as the Ministry of Labour stressed the necessity of women in labor, albeit temporarily to combat the population crisis prior to the inevitable baby boom. “A genuine cultural resettlement was underway,” wrote Moor, who observed that British melodramas of the 1940s, sometimes called women’s films, often placed traditional family values at the center of an ongoing ideological debate about women’s roles in British society. The melodrama had become a major part of British cinema during the war years, given that women occupied the majority of the audience between 1940 and 1945. Women had enjoyed a newfound social freedom, along with a cinema of their own that spoke to their everyday interests. Now that the war had ended, however, women were caught between two ideological extremes: continue to savor that freedom or return to an inhibited role in the patriarchy.

Gender roles had shifted during the war, and again afterwards, much as they had in the United States. Women who worked full-time jobs in the war years were expected to return to their previous domestic roles. Birth rates were down, juvenile crime was up, and women who had been liberated by joining the workforce were blamed for these trends. The Royal Commission on Population reported that family stability depended upon women being in domestic roles, even as the Ministry of Labour stressed the necessity of women in labor, albeit temporarily to combat the population crisis prior to the inevitable baby boom. “A genuine cultural resettlement was underway,” wrote Moor, who observed that British melodramas of the 1940s, sometimes called women’s films, often placed traditional family values at the center of an ongoing ideological debate about women’s roles in British society. The melodrama had become a major part of British cinema during the war years, given that women occupied the majority of the audience between 1940 and 1945. Women had enjoyed a newfound social freedom, along with a cinema of their own that spoke to their everyday interests. Now that the war had ended, however, women were caught between two ideological extremes: continue to savor that freedom or return to an inhibited role in the patriarchy.

The nuns in Black Narcissus mirror this dynamic in postwar British society. Each nun struggles to maintain her spiritual composure against the freedom and temptations around them, working with the knowledge that a Brotherhood had attempted a similar feat before them and lasted only five months. This effect is never more apparent than with Ruth, who is confronted by two ideological poles that seem to drive her into emotional overload—a fit of madness and so-called hysteria. However outmoded this decidedly Freudian reading may be today, such psychoanalytic concepts were popular during the 1940s and doubtlessly influenced both Godden and the screenplay by Powell and Pressburger. Freud writes that hysterical behaviors “obtain an expression that shall be appropriate to their emotional importance” through psychosomatic symptoms. With that in mind, Ruth, who Mother Dorothea describes as a “problem” from the outset, experiences a violent crisis of spirituality against the Sisterhood and its mission, heightened by the intoxicating air around Mopu and inflamed by her desire for Mr. Dean. Her neuroses mark her defiance against the confining Order and its denial of her physical desires. When finally she decides to act on her innermost sexual impulses, she goes to Mr. Dean’s home. With a tinge of madness in her voice, she announces, “I’m done with them,” and she declares her love for Mr. Dean, who has barely said a word to her. Dean declares, “I don’t love anyone!” All at once, Ruth collapses in a fit of rage—sometimes referred to as a red-out given her subsequent attack on Clodagh—and repeats Clodagh’s name again and again as she falls to the floor.

While Mr. Dean represents the sexual freedom and ideological opposite of Ruth’s restrictive life in the Order, Clodagh remains a symbol of what Ruth rallies against. Still, Ruth, though the most pronounced character in the film, is a supporting character in Black Narcissus, which revolves primarily around Clodagh, her mission, her tenuous association with Mr. Dean, and her own spiritual crisis. For every outward expression of Ruth’s crisis, Clodagh experiences a similar doubt pointed inward. She daydreams about her ill-fated romance in Ireland and even smiles at Mr. Dean’s bombastic singing at the Christmas service, moments that The Archers share with the viewer alone. When Clodagh attempts to counsel Ruth, who seems to be coming apart, she accuses Ruth of “thinking too much of Mr. Dean”—a remark that doubles as Clodagh’s admission of her own repressed desire. Lingering conversations and glances exchanged between Sister Clodagh and Mr. Dean, along with their loaded farewell in the last sequence of the film, reinforce their unspoken attraction. To be sure, Ruth is acting out Clodagh’s desire, and it frightens her—she represents Clodagh’s worst impulses externalized. And when Ruth finally plunges to her death in a jealous rage, it serves as a lesson to Clodagh not to allow her impulses to get the best of her. But in terms of British imperialism and the role of women in British society, Clodagh’s story represents the quiet suffering and ultimate breakdown of the woman’s spirit under patriarchal power, whether that be male-dominated British imperialism or Christian order that preaches the word of Jesus Christ. Clodagh seems to be in denial of her role in these institutions, defending that Jesus only “took the shape of a man.” But he was “still a man,” argues Dilip Rai.

Any assessment of this film must also celebrate its extraordinary visual presentation, conjured by Jack Cardiff, who would earn an Oscar for his Technicolor cinematography on Black Narcissus—his second collaboration with Powell and Pressburger after 1946’s A Matter of Life and Death. The film was shot entirely at Pinewood Studios, apart from some exteriors captured at Leonardslee Gardens in West Sussex. From the incredible matte paintings by Walter Percy “Poppa” Day to the sets designed by Alfred Junge, the sheer technical virtuosity put into an otherwise simple story remains astonishing. Powell chose the film’s studio aesthetic for practical and artistic reasons: On the practical end, he wanted to avoid uprooting the cast and crew, many of whom had been away from home during World War II, to a protracted and difficult shoot in India; artistically, Powell could maintain control over every detail at Pinewood. Though, his interest in control meant he relied on familiar white actors such as Hallet, Knight, and Simmons to play Indian characters in an unfortunate choice. Powell, who handled most of the visual aspects of The Archers’ collaborations, admired Walt Disney above all other filmmakers for his capacity to create worlds from scratch. He could establish a similar reign on a studio soundstage, away from the unpredictable environment of an on-location shoot. By crafting every detail onscreen from the ground up, Powell could infuse his visual presentation with a rich symbology that admirer Martin Scorsese heralded as “pure cinema.”

Any assessment of this film must also celebrate its extraordinary visual presentation, conjured by Jack Cardiff, who would earn an Oscar for his Technicolor cinematography on Black Narcissus—his second collaboration with Powell and Pressburger after 1946’s A Matter of Life and Death. The film was shot entirely at Pinewood Studios, apart from some exteriors captured at Leonardslee Gardens in West Sussex. From the incredible matte paintings by Walter Percy “Poppa” Day to the sets designed by Alfred Junge, the sheer technical virtuosity put into an otherwise simple story remains astonishing. Powell chose the film’s studio aesthetic for practical and artistic reasons: On the practical end, he wanted to avoid uprooting the cast and crew, many of whom had been away from home during World War II, to a protracted and difficult shoot in India; artistically, Powell could maintain control over every detail at Pinewood. Though, his interest in control meant he relied on familiar white actors such as Hallet, Knight, and Simmons to play Indian characters in an unfortunate choice. Powell, who handled most of the visual aspects of The Archers’ collaborations, admired Walt Disney above all other filmmakers for his capacity to create worlds from scratch. He could establish a similar reign on a studio soundstage, away from the unpredictable environment of an on-location shoot. By crafting every detail onscreen from the ground up, Powell could infuse his visual presentation with a rich symbology that admirer Martin Scorsese heralded as “pure cinema.”

Indeed, Powell sought a form-follows-function approach to directing, what he described in his autobiography as a unification of “music, emotion, image and voices all blended together into a new and splendid whole.” The idea was not a new one: it went back to Russian theorist Sergei Eisenstein, who argued for a cinematic “unifying principle,” and French director Abel Gance, who wrote about cinema as a “symphony” in his 1929 essay called “The Cinema of Tomorrow.” In Black Narcissus, every individual art form is pointed in the same direction, its meaning rendered through imagery and color. Even Brian Easdale’s music remains a vital component, not merely a background accompaniment but an expression of inner emotions, such as Clodagh’s repressed desires and Ruth’s distorted desires. Moreover, Powell’s decision to shoot at Pinewood Studios allowed him to turn each set piece into a manifestation of Clodagh and Ruth’s hidden emotional state, each heightened through dramatic lighting, splashes of color, and camera angles. In the one scene where Cardiff uses a Dutch angle, for instance, it’s to show Ruth’s panicked reaction to the rush of new patients in the Order’s clinic. At the same time, Powell turns each set into a theatrical projection of Orientalism and desire, the falsely romantic vision of colonialism, and the Order’s surface conflict. Watching the film, every detail has a specific purpose and placement, color above all.

From the moment Sister Ruth first meets Mr. Dean—after a patient’s spraying artery decorates her white habit with crimson blood, and Ruth’s thrill over saving the woman’s life transfers to Mr. Dean, whose deep red shirt matches the blood that exhilarates her—the film’s emphasis on symbolic color becomes apparent. Black Narcissus contains the bold uses of red that would define The Archers’ later films, along with blue shadows and soft filters to distort natural colors, all of which required more than one debate between the filmmakers and Technicolor’s on-set supervisors. The desired heightened effect makes the film readable from color alone, creating a pronounced contrast between the Sisterhood’s white Christian purity and Ruth’s sinful emergence into temptation, marked by a red-infused emphasis on lust and jealousy. In basic religious symbology, the visuals establish the white Clodagh as the Madonna and the red Ruth as the whore, the dichotomy between the spirit and the flesh. The first scenes in Calcutta show the nuns with pale, mask-like faces, the natural pinks of their lips muted. But when they first arrive at Mopu, the nuns remark with delight about the colors of the palace, the flowers in the garden, and the brightness of Dilip Rai’s clothing. Soon enough, they realize hard work is a necessary distraction to fill their spirits, though it’s not always successful: Sister Philippa (Flora Robson) finds herself compelled to fill their gardens with an array of colorful flowers instead of vegetables. When Ruth finally gives over to her desires, she dons a bright red dress and lipstick, and her milky skin accentuates the crazed redness around her eyes, as though this scarlet woman sees red. In a magnified state of psychological rupture, which materializes in ways that resemble a horror film, Ruth, compelled by a monstrous sexual desire, becomes a wraithlike figure with pale skin, darkened eyes, and sweat seeping from her pores—all realized in expressive lighting.

Many critics at the time felt Powell and Pressburger had pushed their visual intensity beyond the realm of good taste. After all, British cinema was not known for an expressive style and visualization, yet The Archers matched the story’s melodramatic heights with an equally passionate aesthetic. Writing in The Nation, James Agee called the result “tedious and vulgar,” largely blaming Godden’s novel, but also the filmmakers’ “dramatic exploitation of celibacy as an opportunity for titillation.” In Agee’s later review of The Archers’ I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), he would accuse Black Narcissus of lacking “taste and modesty.” After seeing the film of her book, Godden declared, “I have taken a vow never to allow a book of mine to be made into a film again”—a vow she soon broke to work closely with Renoir on The River. The National Legion of Decency “condemned” Black Narcissus as an “affront to religion and religious life,” taking particular issue with the notion of Clodagh’s memories of her past romance in Ireland. Despite accusations against the film’s perceived gaudy uses of color and tawdry subject matter focused on the sexual desires of nuns, the film earned two Academy Awards, one for Cardiff’s cinematography and another for Junge’s sets. In 2011, Time Out placed the film, and five others by Powell and Pressburger, on their list of the 100 best British films ever made.

Many critics at the time felt Powell and Pressburger had pushed their visual intensity beyond the realm of good taste. After all, British cinema was not known for an expressive style and visualization, yet The Archers matched the story’s melodramatic heights with an equally passionate aesthetic. Writing in The Nation, James Agee called the result “tedious and vulgar,” largely blaming Godden’s novel, but also the filmmakers’ “dramatic exploitation of celibacy as an opportunity for titillation.” In Agee’s later review of The Archers’ I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), he would accuse Black Narcissus of lacking “taste and modesty.” After seeing the film of her book, Godden declared, “I have taken a vow never to allow a book of mine to be made into a film again”—a vow she soon broke to work closely with Renoir on The River. The National Legion of Decency “condemned” Black Narcissus as an “affront to religion and religious life,” taking particular issue with the notion of Clodagh’s memories of her past romance in Ireland. Despite accusations against the film’s perceived gaudy uses of color and tawdry subject matter focused on the sexual desires of nuns, the film earned two Academy Awards, one for Cardiff’s cinematography and another for Junge’s sets. In 2011, Time Out placed the film, and five others by Powell and Pressburger, on their list of the 100 best British films ever made.

Black Narcissus is not merely an exhibition of unified aesthetics that drive the story, although many modern assessments dwell on those aspects—and with good reason. This is an uncommonly beautiful and evocative film, even for Powell and Pressburger, whose streak of films from the early 1940s to their final masterpiece, The Tales of Hoffmann from 1951, often explored the limits of the cinematic apparatus. The unforgettable imagery used to portray Ruth’s state of madness and sexual repression, sharpened by the narrow angles on Byron’s face, have cemented their place among the most powerful sights in all of cinema. However, through the contexts of postcolonialism and women in postwar British society, the film represents another kind of landmark. It portrays the traditions of religion and imperialism as restrictive and flawed, leaving women inhibited by establishments designed by men. There are enough frontiers to conquer, enough Otherness to take possession of on the home soil of one’s own mind and spirit, making any attempt at colonization an exercise in doomed pride. The filmmakers seem to yearn for a medium between piety and outright carnality, both of which are equality vain.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Avshalom!)

Bibliography

Christie, Ian. Arrows of Desire: The Films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Faber & Faber, 1994.

Christie, Ian. Powell, Pressburger and Others. BFI (British Film Institute), 1978.

Christie, Ian and Moor, Andrew, eds. The Cinema of Michael Powell. BFI (British Film Institute), 2005.

Eisenstein, Sergei. The Film Sense. Translated and edited by Jay Leyda. Faber and Faber, 1968.

Freud, Sigmund. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works, Vol. XCII. Hogarth Press, 1955.

Moor, Andrew. Powell and Pressburger: A Cinema of Magic Spaces (Cinema and Society). I.B. Tauris; Distributed in the U.S. by Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Powell, Michael. A Life In Movies: An Autobiography. Heinemann, 1986.

Powell, Michael. Million Dollar Movie. Heinemann, 1992.

Saïd, Edward W. Orientalism. Pantheon Books, 1978.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review