The Definitives

Black Legion (1937)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

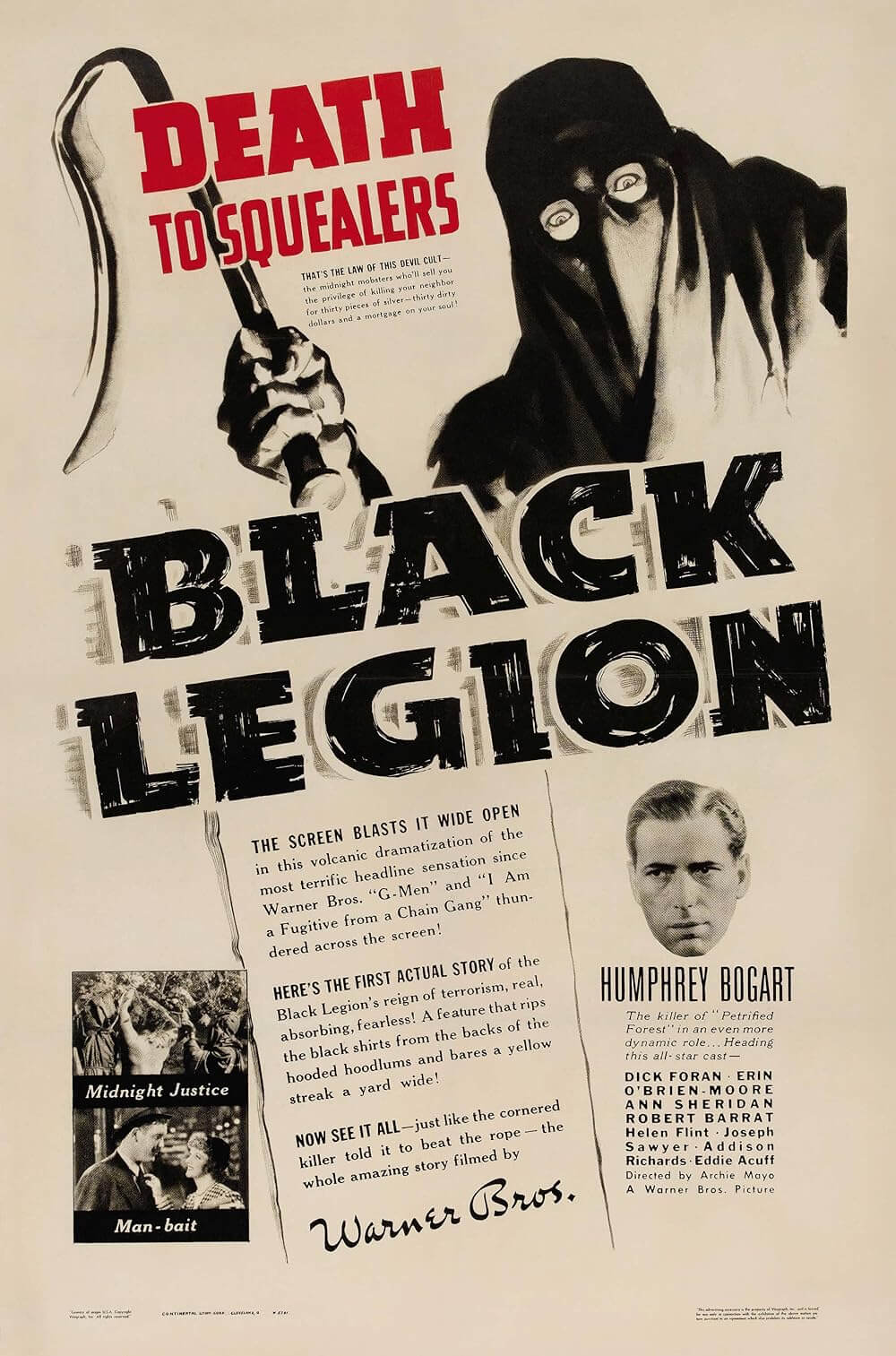

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor that finally convinced American isolationists to join World War II, Hollywood studios concealed their criticism of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party in stories that exposed the danger of fascistic ideologies on the homefront. Black Legion, a Warner Bros. production from 1937, tells a real-life story about a group of racist, intolerant thugs whose organization sought to rid the country of so-called “foreigners” in the name of Americanism and white supremacy. A condemnation of racism, anti-Semitism, and intolerance, the film, directed by studio mainstay Archie Mayo, with uncredited help from Michael Curtiz, offers a message that functions less as propaganda and more like social responsibility. Warner Bros. produced Black Legion to call attention to the Nazism spreading throughout the world. But their film implicates the rise of American fascism during the same period, while it condemns the illogical nature of racism and despotic leaders who use hatred and fear to feel powerful. The film draws parallels between the Nazism abroad and the fascistic ideologies that persist in the United States, endangering the idealistic equality that some Americans hold dear. Viewers at the time would feel galvanized against Nazis and more attuned to the problem of racism at home. Contemporary audiences will recognize a familiar pattern of racial hatred emerging once more in disturbing, violent ways.

Unlike most Hollywood studios, Harry and Jack Warner used their company to combat the fascist tide as early as 1933. The sons of Polish émigrés who were forced to hide their Jewishness due to rampant anti-Semitism in their home country, Harry and Jack—along with their brothers Sam and Albert—had been aware and suspicious of the Nazi threat since Jack visited their Berlin offices in 1928, where he saw “the first goose-stepping evidence of the coming Nazi march.” Running the most efficient studio in Hollywood, Harry remained devoted to his religion, whereas Jack ignored his Jewishness and basked in the power (and womanizing) afforded by his position. Nevertheless, Harry insisted that Warner Bros. take a stand against Nazism and expose Hitler. Their first film to address Nazis by name would not arrive until 1939. But on September 18, 1933, Warner Bros. released an animated Looney Tunes short called Bosko’s Picture Show that portrayed Germany as led by Adolf Hitler, an absurdly funny caricature in lederhosen, marking the first time Hitler appeared on screens outside of newsreels. In the ensuing years, Warner Bros. released dozens of titles that depicted fascistic ideologies as dangerous, showed underdogs winning victories over despotic rulers, and became the first major Hollywood studio to make a motion picture openly condemning Nazism with Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939). Facing oversight from the Production Code Administration (PCA) and the State Department, and denunciations from the isolationist community, the studio, and many others in Hollywood at the time, put anti-Nazi messages into films through indirect references.

Not long after England declared war on Germany, Jack Warner claimed his family’s studio would not engage in propaganda pictures: “America is neutral, and we are Americans. Our policy is one hundred percent neutrality. There will be no propaganda pictures from Warner Bros.” The studio’s statement meant only that they would not openly call for the United States to join the war effort; instead, the studio released a number of films sympathetic to the Allied Forces and condemning fascistic ideologies. The neutrality was Rooseveltian in the sense that Warner Bros., from a certain point of view, did not believe it was making propaganda. They called their motion pictures message films. Just as Roosevelt did not believe that his administration was taking gradual steps to bring the United States into the conflict with its “all aid short of war” position, Warner Bros. did not believe its dramatizations told audiences what to think. Rather, the Warners empowered their viewers to weigh their beliefs against the anti-fascist material before them and decide how they felt about the stories told. Then again, Harry Warner was vocal in his desire to “expose Hitler” as early as 1933, but the systematic obstacles in his way delayed any significant movement until several years later. If bluntly attacking Hitler was too much for American viewers in the early-to-mid-1930s—at least, according to American censors—then Harry would look for trouble on the homefront. What he found was several right-wing fascist groups that had, just as in Germany and other countries, formed in the United States after the First World War and during the Great Depression.

In a familiar turn of events that would repeat through history during the Nixon, Reagan, and Trump administrations, the fascistic discord in the first half of the twentieth-century began with the silent majority. Rather than explore practical solutions to the economic situation, Protestant farmers from the Midwest and “downtrodden whites” from the South assembled into dozens of crypto-fascist organizations in the United States. Each group claimed to have pure Christian intentions to invigorate the American cause, drawing from xenophobic and religious prejudices that had existed since the Protestant Reformation. These reactionary groups sought someone to blame for the Depression, and they assigned culpability to the immigrant population of Jews, African Americans, Central and Eastern Europeans, and Catholics. American fascists behind groups like the Christian Front sought to remove the so-called foreign threat from the heartland and spread anti-Semitic rhetoric on radio broadcasts or their periodical Social Justice, claiming that Jews and other immigrants took away jobs from pure Americans. Many of these groups also aimed their rhetoric at Hollywood, positing that its Jewish studio heads were part of a far-reaching Communist conspiracy that included stealing jobs from hard-working Americans, controlling the American mindset through the movies, and engineering the First World War.

Harry Warner resolved to make a film about the most well-known and aggressive of these groups at the time, which called itself the United Brotherhood of America, or Black Legion. Formed in Ohio with members throughout several Midwest states, including Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan, the Black Legion was founded by Dr. William Jacob Shepard, a former leader of the Ku Klux Klan’s resurgence in the 1920s following D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). KKK leader Virgil Effinger eventually took over and set aside the group’s signature white robes for more intimidating black outfits. The Black Legion also wore bicorne hats marked by a skull and crossbones insignia, giving them the almost comical look of robed pirates. But there was nothing amusing about their tactics. With upwards of 100,000 members at its height, the Black Legion under Effinger was more outwardly committed to violence than the KKK. They recruited police officers, National Guardsmen, and former soldiers in their ranks, along with ambitious men who seemed to have a future in politics. As one journalist observed at the time, “Those who could not think for themselves but allowed themselves to be impressed as blind dupes, the cowardly, sadist types, were candidates for the Nazis and the Legion.” Effinger assigned the group’s Legionnaires to flog Jews, whom they believed caused the economic crisis. The Legion also bombed the headquarters of workers unions who hired immigrants and set fire to the homes of Catholics who strayed from “true” Christian values. In Effinger’s attempt to create a mythology around his organization, he rewrote history, as despotic leaders do, and claimed the Black Legion led the American Revolution and carried out the Boston Tea Party. Effinger even saw himself as president someday, ruling with an iron fist.

While Effinger made political moves for a coup d’état, his organization bombed storefronts owned by liberals and suspected Communists; they even explored the possibilities of biological warfare when they considered methods of infecting Jewish communities with typhus by contaminating their milk and cheese deliveries. But it was Dayton Dean, an Army Major, whose murders shined a spotlight on the Black Legion and ended their run of American terrorism. Dean’s trial in 1936 and 1937 exposed the group’s racist ideology and violent methods. While accused of murder, Dean identified fifty members of the group that had conspired to kill a Catholic auto worker named Charles Poole. The group believed Poole had beaten his pregnant Protestant wife, and they retaliated by kidnapping Poole from his home, flogging him, and then shooting him five times. The case earned national attention and ultimately led to the Black Legion’s downfall and murder convictions for many members of the group. Dean’s testimony revealed other murders and violent acts perpetrated by the Legion. For instance, in 1935, Dean had killed an African American, the World War I veteran Silas Coleman, whom Dean had targeted because he wanted to know “what it felt like to kill” a man of color (Dean used the N-word).

While Effinger made political moves for a coup d’état, his organization bombed storefronts owned by liberals and suspected Communists; they even explored the possibilities of biological warfare when they considered methods of infecting Jewish communities with typhus by contaminating their milk and cheese deliveries. But it was Dayton Dean, an Army Major, whose murders shined a spotlight on the Black Legion and ended their run of American terrorism. Dean’s trial in 1936 and 1937 exposed the group’s racist ideology and violent methods. While accused of murder, Dean identified fifty members of the group that had conspired to kill a Catholic auto worker named Charles Poole. The group believed Poole had beaten his pregnant Protestant wife, and they retaliated by kidnapping Poole from his home, flogging him, and then shooting him five times. The case earned national attention and ultimately led to the Black Legion’s downfall and murder convictions for many members of the group. Dean’s testimony revealed other murders and violent acts perpetrated by the Legion. For instance, in 1935, Dean had killed an African American, the World War I veteran Silas Coleman, whom Dean had targeted because he wanted to know “what it felt like to kill” a man of color (Dean used the N-word).

When planning their picture about the Black Legion, producer Hal B. Wallis and writers Abem Finkel, Robert Lord, and William Wister Haines, met with objections from the PCA. Will Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), served as chairman of The Hays Code, as it was colloquially known, starting in 1930, but Joseph Breen led the enforcement division. The Hays Code claimed to administer “good taste” after public outcry noted that films “may be directly responsible for spiritual or moral progress, for higher types of social life, and for much correct thinking.” Throughout the Golden Age of Hollywood, the PCA demanded that studios clean up their depictions of crime, drugs, sex, hygiene, nudity, and other subjects deemed morally inappropriate for viewers. Although they did not have the power to ban films, their seal of approval often determined whether exhibitors would show a picture. The studios needed that seal, giving Breen an incredible amount of control over Hollywood’s output. And Breen pointed a sharp eye toward any material pertaining to international political situations, adhering to the letter of the Code, which affirmed, “The history, institutions, prominent people and citizenry of all nations shall be represented fairly.” However, Breen’s choices at this time frequently sought to pacify the criticism of the German and Italian fascist governments; after all, several American industries still depended on the global marketplace to ensure profits in the 1930s. But Breen’s motivations also remained biased given his anti-Semitic and anti-Communist views.

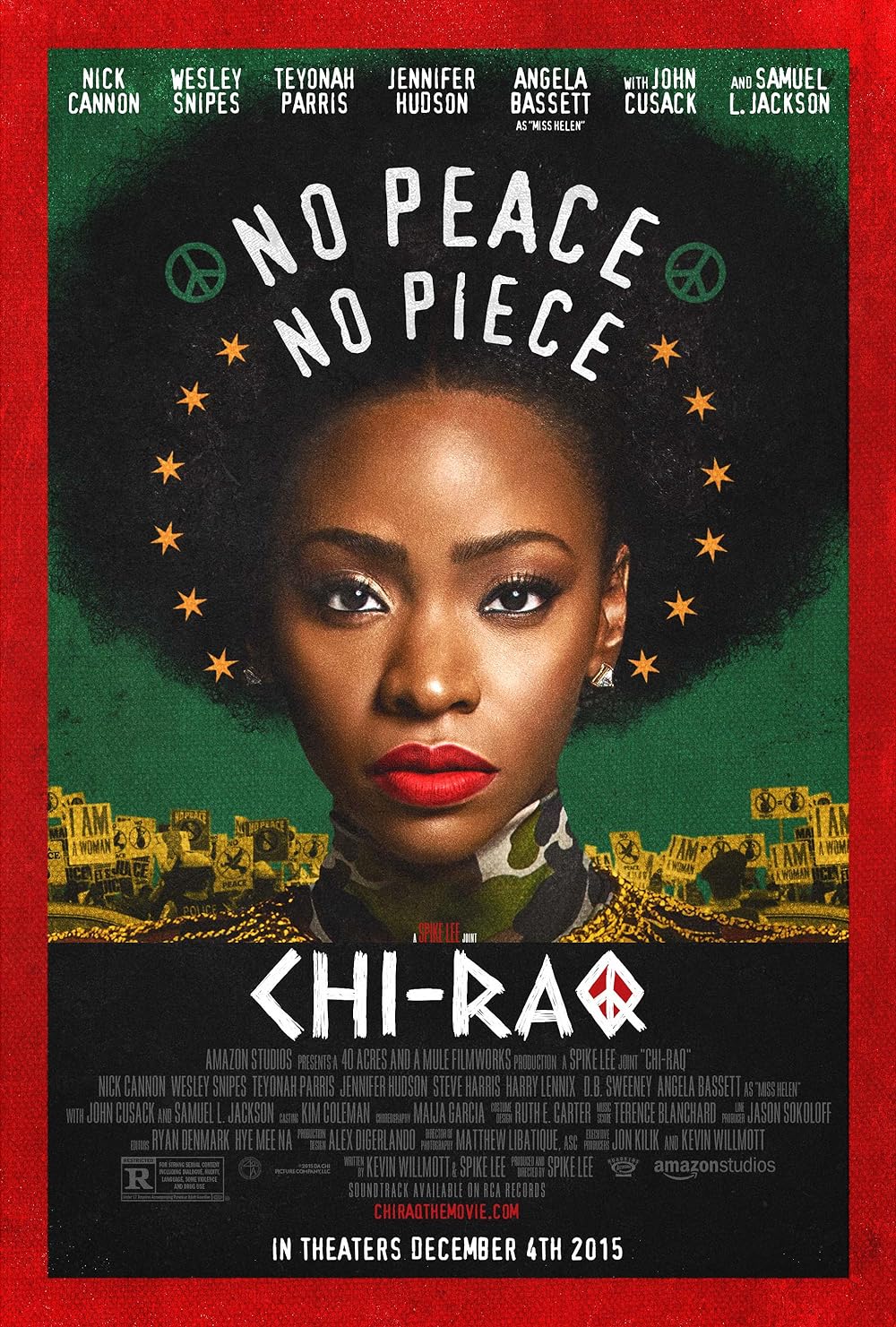

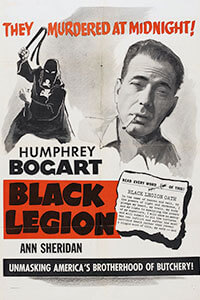

Warner Bros. had to proceed carefully to avoid losing the picture’s message to Breen’s scissors. Fortunately, the studio already had a reputation for its ripped-from-the-headlines approach, having commented on Prohibition-era crime with a slew of gangster pictures such as William A. Wellman’s The Public Enemy and Mervyn LeRoy’s Little Caesar, both released in 1931. Despite Black Legion’s origins in recent American history, the PCA forced Wallis to cut back on the film’s depiction of anti-Semitism. They worried that any perceived anti-Semitic biases would create a connection to Nazi Germany, thus drawing an obvious parallel between Nazism and American fascist groups, which would in turn alert American viewers to the problem in Europe. Breen’s oversight also impacted the casting. Edward G. Robinson, who was originally hired in the leading role of Frank Taylor, a fictionalized version of Dayton Dean, was deemed too foreign-looking to be a member of a fascist organization—the implication being that Robinson’s European appearance might imply the fascistic surge in America had come from abroad. Ironically, Breen’s choice meant the studio took a risk on young Humphrey Bogart instead, whose casting lends the film a more sinister meaning: that fascism can affect the average American. Breen and the PCA were not the only threat, however. Elsewhere, Wallis was forced to increase security on the studio lot during the production to avoid retaliation from former Black Legion members. Effinger, who was not convicted during the Dean trial, already began to form a new group called the Patriotic Legion of America—Catholics were now allowed, dependent on racial background—and there were murmurs of reprisals on the production.

The screen story follows Bogart’s Frank Taylor, a hard-working everyman—complete with “the cutest wife and kid you ever saw,” he remarks—who seems to be next in line for a promotion at his auto factory. Convinced that he’s owed the American Dream, he promises his wife Ruth (Erin O’Brien-Moore) a new vacuum cleaner, coat, and automobile. But when he’s passed over for the promotion, and management chooses the harder-working Polish immigrant named Dombrowski (Henry Brandon) who has invented a mechanism to make the factory run smoother, Frank grows bitter. He becomes careless at his job and sulks in his disappointment. Soon enough, a coworker tells Frank, “You don’t have to be pushed around by no foreigners,” and advises him to attend a Black Legion meeting that night. At the secretive gathering in the basement of a drugstore, a German-accented speaker, an evident parallel to Hitler, spews out fascistic rhetoric: “If we unite with the millions of other red-blooded Americans under the banner of the Black Legion, we are invincible. With fire and sword, we’ll purge the land of these traitorous aliens and strangle their every deadly scheme ‘till once more our beloved stars and stripes will wave over a united nation—free, white, one-hundred-percent American!” The group promises to secure people like Frank better jobs by ridding the area of “foreigners,” a term that 1930s audiences would doubtless read as any non-white or non-Protestant person. The implication against Jewish, African American, and other ethnicities was unmistakable.

Frank, convinced by this hate-speech, resolves to join the Black Legion. In their ranks, he no longer feels alone, and his anger is emboldened because others like him have chosen to feed on their own emotions and “purify” America. He feels powerful because he belongs to a secret group and gets to carry a gun. Before long, he joins other members who gladly participate in burning down the Dombrowski farmhouse, an act of domestic terrorism and, for Frank, an act of petty revenge over a promotion that he felt he deserved. After blindfolding and sending Dombrowski and his father on a train out of town, Frank gets that promotion and buys that new car, vacuum, and coat for his wife. But after a montage of raids and beatings of members of his community, he grows more distant from Ruth and more committed to the Legion. He spends more time recruiting new members on the job than actually working, and it gets him fired. Unemployed and angrier than ever, Frank begins drinking heavily, abusing and cheating on his wife, and ignoring his child, until finally his family leaves him. The film shows how the Black Legion eats away at Frank and causes him to change, betray his wife, and lose everything he has. When Frank’s best friend and neighbor, Ed (Dick Foran), eventually confronts him, calling the group an outfit for “half-wits,” Frank worries that Ed will talk. He retaliates by trying to frame Ed as a wife-beater, leading to a botched kidnapping that ends when Frank fires several bullets into Ed’s back. Frank is soon captured and put on trial, where, guilt-stricken, he identifies the Black Legion’s members and, with them, earns a life sentence for murdering his friend.

Black Legion may not address anti-Semitism or acknowledge the connections between the Black Legion’s ideology and Nazi beliefs directly, but its commentary on the dangers of racism, xenophobia, and American fascism is evident. The screenwriters incorporate lofty speeches to make the implications unambiguous. A radio broadcast reporting on Frank’s case announces, “Any organization that appeals to narrow prejudice and attempts to enforce its creeds by violence is inimical to our democracy and repugnant to the ideals of every good Christian and every decent American.” Later, the judge in Frank’s case (Samuel S. Hinds) makes a damning speech to the Black Legion: “We cannot permit racial or religious hatreds to be stirred up, so that innocent citizens become the victims… We cannot permit unknown tribunals to pass judgments nor punishments to be inflicted by a band of hooded terrorists. Unless all of these illegal and extra-legal forces are ruthlessly wiped out, this nation may as well abandon its Constitution, forget its Bill of Rights, tear down its courts of justice, and revert to the barbarism of government by primitive violence.” The judge’s remarks speak to the Black Legion’s policies, but for Harry Warner and the rest of Warner Bros., the judge’s speech provided an allusion to Nazi Germany.

Furthermore, Black Legion creates an association between fascism and Prohibition-era gangsterism. Audiences in the United States were accustomed to seeing gangsters condemned in the movies. When Frank first joins the Black Legion, they hold a gun to his head and force him to read an oath of allegiance, whose vaguely demonic language the screenwriters borrowed from a similar oath written for Confederate guerillas during the Civil War. Frank promises “in the name of God and the Devil” and “by the powers of light and darkness […] here under the black arch of Heaven’s avenging symbol” to defend the Black Legion or suffer grotesque bodily punishment. Mayo shoots the sequence at night, a nearby fire supplying an ominous light source. Black Legion is a film whose cruel deeds take place under cover of night and shadow, a visual motif that, along with the low angles that create a sense of danger, implies the group’s devious and underhanded nature. Despite the initiation’s theatrics, Frank is immediately ordered to report to the Office of Supplies where he must pay “the nominal sum of $6.50” for his uniform, and then the Office of Ordinance for “a Black Legion special, a regularly $30 revolver for the small sum of $14.95.” The ideologies of such a group, then, are formed by salesman-leaders, who use the proceeds to line their own pockets. The film alludes to groups like the Black Legion or the Nazis as nothing more than rackets, no better than the previous decade’s gangsters who get a thrill from the perks of their power.

For moviegoers, Bogart’s presence alone was enough to create an association between fascists and gangsters. In the 1930s, Bogart played almost exclusively seedy villain roles. Before Black Legion, he appeared in two Warner Bros. gangster pictures from 1936, Mayo’s Petrified Forest and William Keighley’s Bullets or Ballots, as double-crossing and violent gangsters. In Black Legion, Bogart plays his role as Frank Taylor in the key of a wannabe gangster. In one scene, his character stands in the mirror with his Black Legion issued gun, practicing his draw and admiring himself. At any moment, it seems like he might begin a “You talkin’ to me?” routine. Although the scene describes how such an organization is rooted in power, and the image of power, more than a devotion to any ideology, it also underscores how Taylor has allowed himself to be brainwashed to feel big. Initiates like Frank swore an oath against the United States’ laws, agreeing to purger themselves if captured. As historian Michael E. Birdwell notes, they vowed to “rid Christian America of African Americans, immigrants, Jews, and Catholics; promised to arm themselves as quickly as possible; and supported the speedy, unforgiving justice of the lynch law.” Frank had signed up to be a simple gangster, but he wound up becoming a member of a murderous, white supremacist organization that has existed in American by various names, from the KKK to the fascist groups emboldened by the Presidency of Donald Trump.

Black Legion implies that fascist organizations have xenophobic members, and they are capable of transforming decent people into the worst versions of themselves. They use the hope of a better life to oppress others and justify racial violence in the name of patriotism. Fascists have also monetized their rackets for profit, exploited their followers with hollow ideas, and, therefore, should be met with suspicion. An average citizen like Frank Taylor joined the Black Legion by giving in to anger, and his allegiance to their cause meant his otherwise good-hearted “Americanism” deteriorated. Through the course of the film, Frank’s work at the factory becomes sloppy, leading to an accident; his wife distrusts him, inciting them to separate; and Frank tragically kills his best friend to support their cause. Fascism corrupts, absolutely, the film seems to say. Black Legion also demonstrates an idealistic faith in American institutions, such as the justice system, which is designed to protect against fascism from entering the country. Regardless of his willingness to testify against the group, Frank receives no mercy in the film, just as Warner Bros. gangsters rarely survived to the end. Although James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson usually ended up shot to death or strapped to an electric chair in their gangster pictures, Bogart’s character must live with his choices for the rest of his life behind bars. The film’s hope for justice is inspired, although perhaps ignorant of the institutions that allow hate groups to persist in America.

Even so, critics hailed the studio’s willingness to avoid a happy ending. They praised the film’s topical cautionary tale about how people can be preyed upon and transformed into something evil when they submit to fear and violence as a solution. Otis Ferguson’s original review in the New Republic, titled “Truth in Fiction,” hailed Black Legion for its courageous anti-fascist message during such divided times in America, though he acknowledged the message could have been more confronting if not for the PCA: “The picture is a very good illustration of what is possible and what is too much for the time.” The critic in Time magazine called the film “one of the most effective in Warner Brothers’ series of industrial problem plays.” Many critics commended the studio for refusing to grant Bogart’s character a reprieve for coming forward. The critic in Literary Digest claimed that “Hollywood grows up” with the ending. The National Board of Review also named Black Legion one of 1937’s best films and Bogart one of the year’s best actors. And when all was said and done, Wallis avoided violent retaliation or lawsuits from former Black Legion members. Still, the KKK filed a suit against Warner Bros. for patent infringement since the production used their logo. The judge threw the case out and demanded the KKK pay the court fees.

While Black Legion uses a contemporary story to demonstrate the threat of fascism at home and abroad, Warner Bros. also went further into history to find similar allegories. Under the eye of watchdogs looking for evidence of ideological bias, Hollywood’s most common method of instilling anti-fascist messages in the pre-Pearl Harbor era was allegory, historical and contemporary. Warner Bros. released dozens of films that fit this description. In William Dieterle’s Juarez (1939), the studio denounced foreign dictatorships with the story of Napoleon II’s attempt to rule Mexico and found a hero in Benito Juarez, who resisted French rule. In an adaptation of Jack London’s book The Sea Wolf, Michael Curtiz’s 1941 adaptation centers on Edward G. Robinson’s madman captain, whose crew rallies against his cruelty and absolutism, which lead to his demise. Despite having the cover of allegory to protect these films, critics and audiences had no difficulty reading the subtext. Among the most popular was The Life of Emile Zola (1937) by William Dieterle, featuring Paul Muni as the titular French writer. Although structured as a standard Hollywood historical biopic of the era, the film’s subject matter exposes the dehumanizing reality of anti-Semitism and racial prejudice. The film performed well at the box-office, received resounding attention critically, and later won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture, which suggests viewers, critics, and those in the industry welcomed its humanistic, anti-fascist message. After touching briefly on Zola’s emergence as an author and his friendship with painter Paul Cézanne, Zola’s defense of French-Jewish officer Alfred Dreyfus dominates the film’s last two-thirds. Dreyfus was a famous victim of a military conspiracy and institutional anti-Semitism. In defending him, Zola faces jail time and ostracization by opposing the popular French military, as nationalized attitudes refuse to accept that their institutions are capable of racism and deceit. The film raised questions about one’s blind devotion to their country when it does something morally wrong.

Much like Confessions of a Nazi Spy would do two years later by directly addressing Nazism in America, Black Legion explores the idea that it can happen here. The country’s isolationist majority preferred to think of Nazi Germany as “Europe’s problem,” but Black Legion reminded viewers that fascism is not some faraway concern—it’s right here on American soil, right under our noses. And unless it’s exposed as an ideology fueled by hatred and bigotry, and forestalled altogether, it promises to transform the country from a democracy into an oppressive dictatorship—where the devoted supporters of a despotic leader follow without question, having been convinced of their own racial and moral superiority. What the film conveys so well is how hate organizations can persuade more than just crackpots to their cause; they seduce the average American by promising a sense of power and authority, until members have adopted the group’s dangerous rhetoric and become radicalized into acting on their hatred. But Black Legion shows the group is nothing more than a band of gangsters, mere thugs who conform to an intolerant worldview that goes against ideals of freedom and empathy. And while 1930s audiences watched the film and saw a veiled commentary on local fascism and the Nazi Party overseas, today’s audiences will recognize a similar, virulent strain of racial violence and intolerance spilling onto the streets, heightened by dangerous hate-mongering rhetoric that expels reason and preys on fears, jeopardizing once more the hope for American equality.

Bibliography:

Barker, Jennifer Lynde. The Aesthetics of Antifascist Film: Radical Projection. Routledge, 2013.

Birdwell, Michael E. Celluloid Soldiers: Warner Bros.’s Campaign Against Nazism. New York University Press, 1999.

Dick, Bernard F. The Star-Spangled Screen: The American World War II Film. The University Press of Kentucky, 1985.

Doherty, Thomas. Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939. Columbia University Press, 2013.

Jewell, Richard B. The Golden Age of Cinema: Hollywood 1925-1945. Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Koppes, Clayton R., and Gregory D. Black. Hollywood Goes to War: How Politics, Profits and Propaganda Shaped World War II Movies. University of California Press, 1987.

McLaughlin, Robert L., and Sally E. Parry. We’ll Always Have the Movies: American Cinema During World War II. The University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Nugent, Frank S. “The Strand’s ‘Black Legion’ Is an Eloquent Editorial On Americanism—’Conflict’ Opens at the Globe.” The New York Times, 18 January 1937. http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9807E0DB1638EF3ABC4052DFB766838C629EDE. Accessed 2 September 2020.

Powaski, Ronald E. Toward an Entangling Alliance: American Isolationism, Internationalism, and Europe, 1901-1950. Greenwood Press, 1991.

Norwood, Stephen H. Strikebreaking & Intimidation: Mercenaries and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century America. The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

(Note: The above was excerpted and re-edited from a Master’s thesis, An Undeclared War: Hollywood’s Pre-Pearl Harbor Anti-Nazi Cinema.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review