The Definitives

Batman Begins

Essay by Brian Eggert |

After training in the arts of deception, theatricality, and mass engagement in the Himalayas with clandestine ninjutsu vigilante group The League of Shadows, young Gotham City billionaire Bruce Wayne returns home after a long absence. On his private jet back, he lays out the foundations of a plan to his family’s loyal servant Alfred about how he intends to use his money and newfound abilities to fight injustice: “I’m going to show the people of Gotham their city doesn’t belong to the criminals and the corrupt… People need dramatic examples to shake them out of apathy and I can’t do that as Bruce Wayne. As a man, I’m flesh and blood. I can be ignored. I can be destroyed. But as a symbol… As a symbol, I can be incorruptible. I can be everlasting.” Herein is the central theme of Batman Begins, a film not about a superhero, but about a man who uses his considerable means to transform himself into a symbol.

Written by David S. Goyer and director Christopher Nolan, Batman Begins transforms the superhero genre and transcends its limitations with a film that is a moving, emotionally involving, and exciting experience. It begins with the formation of an idea. And indeed, the conceptualization of Batman since the character’s inception has undergone innumerable adjustments and renovations over his nearly seventy years in comic books, television, and film—from vigilante to detective, from campy hero to public enemy, from Caped Crusader to The Dark Knight. Batman Begins reinvents the iconographic comic book character in near-operatic terms, finally actualizing the depth and emotional potential that remained untapped through so many adaptations. Nolan, drawing heavily from continuities shaped by Frank Miller and Bruce Timm, erases decades of mediocre superhero moviemaking and elevates Batman to a potent source for dramatic, symbolic storytelling.

Retelling the hero’s origin story, Nolan describes Batman’s starting point with sobering consequence, relying on symbolism to infer the character’s grand theatrical transformation within the narrative. His parents gunned down before him by Crime Alley thug Joe Chill, child Bruce Wayne (heartrendingly acted by Gus Lewis) is scarred by the incident and stricken by an ensuing obsession with vengeance. Upon maturing into an adult, Wayne (now Christian Bale) vows to punish injustice without becoming a murder-bound vigilante himself. His pledge ultimately pits him against Gotham City’s entire urban sprawl, riddled with both organized and unfettered crime. This basic outline of Batman’s widely known origin story is the only consistent aspect throughout the character’s various mythologies. Nolan’s film deepens the origins, making Wayne’s battle more about overcoming his anger, childhood fears, and guilt—all present since the night his parents were murdered—rather than defeating some villain. Indeed, the central conflict of Batman Begins is largely psychological. And though these themes have always stewed under the surface of Batman’s various incarnations, they have never done so with as much dramatic power as Nolan structures here.

Retelling the hero’s origin story, Nolan describes Batman’s starting point with sobering consequence, relying on symbolism to infer the character’s grand theatrical transformation within the narrative. His parents gunned down before him by Crime Alley thug Joe Chill, child Bruce Wayne (heartrendingly acted by Gus Lewis) is scarred by the incident and stricken by an ensuing obsession with vengeance. Upon maturing into an adult, Wayne (now Christian Bale) vows to punish injustice without becoming a murder-bound vigilante himself. His pledge ultimately pits him against Gotham City’s entire urban sprawl, riddled with both organized and unfettered crime. This basic outline of Batman’s widely known origin story is the only consistent aspect throughout the character’s various mythologies. Nolan’s film deepens the origins, making Wayne’s battle more about overcoming his anger, childhood fears, and guilt—all present since the night his parents were murdered—rather than defeating some villain. Indeed, the central conflict of Batman Begins is largely psychological. And though these themes have always stewed under the surface of Batman’s various incarnations, they have never done so with as much dramatic power as Nolan structures here.

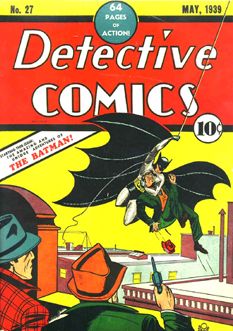

Created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger for DC Comics in 1939, Batman first appeared in Detective Comics, issue #27. Unlike contemporary heroes such as Superman, Kane’s creation had no uncanny powers, just human endurance and initiative, wealth and intelligence. Perhaps this is why Batman remains so appealing; he represents the limit of human potential. Those limits are superhuman to be sure, though so rarely tapped by the populous. Kane originally conceived the “Bat-Man” with a domino mask, stiff wings attached to the arms, and red tights. His design was later re-envisioned by Finger for a more ominous look: no exposed skin but his mouth, a cowl, gloves, a flowing cape in which he could wrap himself like a gargoyle, and glowing, bat-like eyes. While Kane negotiated a byline “Created by Bob Kane” when he signed his character over to DC, Finger was left uncredited in spite of his significant contribution, which even included selecting the name Bruce Wayne as the hero’s alter-ego. Only after Finger’s death in 1974 did DC acknowledge the writer’s ongoing development of Batman and a number of the comic’s quintessential villains.

Kane and Finger initially devised Batman to kill wrongdoers in pulp fiction detective style, underlining the vigilante-hero’s distance from the judicial system. But after a particularly violent storyline where Batman shot several criminals to death with a gun, editor Whitney Ellsworth insisted the hero adopt a more official attitude. Instead of tracking criminals and killing them, Batman would use his unconventional means to punish under the guise of the law (regardless of how inefficient The System often proved to be). Batman’s gun was replaced with a “batarang” and utility belt, he turned over criminals to his official counterpart Commissioner James Gordon, and Arkham Asylum became the temporary hub for the hero’s rich assortment of supervillains (all of whom would escape again and again to rein terror on Gotham). But it is Bruce Wayne’s unshakable devotion to his own ideal that sets him apart. He must be better than the criminals he seeks to take down; he must never kill. Even if his actions only submit criminals to judgment from a corrupt system of law, in remaining doggedly faithful to his principles, he sets an immovable example.

Kane and Finger initially devised Batman to kill wrongdoers in pulp fiction detective style, underlining the vigilante-hero’s distance from the judicial system. But after a particularly violent storyline where Batman shot several criminals to death with a gun, editor Whitney Ellsworth insisted the hero adopt a more official attitude. Instead of tracking criminals and killing them, Batman would use his unconventional means to punish under the guise of the law (regardless of how inefficient The System often proved to be). Batman’s gun was replaced with a “batarang” and utility belt, he turned over criminals to his official counterpart Commissioner James Gordon, and Arkham Asylum became the temporary hub for the hero’s rich assortment of supervillains (all of whom would escape again and again to rein terror on Gotham). But it is Bruce Wayne’s unshakable devotion to his own ideal that sets him apart. He must be better than the criminals he seeks to take down; he must never kill. Even if his actions only submit criminals to judgment from a corrupt system of law, in remaining doggedly faithful to his principles, he sets an immovable example.

Following this notion, Nolan and co-writer Goyer begin their mythology with Wayne, played with appropriate gravitas by Bale. The film opens with Wayne, who has willingly condemned himself to a Far East prison, where he trains his body and mind in combat against hardened inmates. Having resolved to fight the criminality inherent in Gotham’s underworld, he has traveled the world learning the nature of the criminal and meanwhile struggles to center his emotions. They need centering, he finds, after his parents’ murderer is released from prison by becoming an informant; Wayne plans to assassinate the killer, but his plan is foiled when the mob takes Chill down first. Consumed by unfocused anger, weakened by guilt, Wayne escapes his pampered billionaire lifestyle to understand his enemy, landing himself in the Asian prison. Here, future sensei and father figure to the parentless Wayne, Henri Ducard (Liam Neeson), arrives in Wayne’s prison cell and offers to teach Self-mastery and fear control so he might become an invisible, unstoppable force: the way of the League of Shadows, led by mysterious figure Ra’s al Ghul (Ken Watanabe). Wayne’s already considerable martial arts skills are perfected, but only so he might become more than a mere living weapon: an idea.

Even as he becomes this idea, there is still a very human conflict inside him. Nolan presents Bruce Wayne as a shattered individual who has, in a way, consciously constructed a split-personality for himself when he becomes Batman, all as a result of his childhood trauma. During his training, he seems preoccupied with instilling a replacement father figure in Ducard. But ultimately he refuses the League’s final test of his loyalty when he’s asked to kill a local thief; and after, a moral cleansing of Gotham City on a citywide scale. The League intends to help along Gotham’s path of self-destruction; this is something they’ve done for centuries, from Rome to London. When a city’s time comes, they drop the blade. In rebelling against The League and Ducard, Wayne has accepted that he no longer needs to dwell on his absence of a father figure. He no longer needs one. His paralyzing childhood dread of bats surmounted, his anger and guilt better understood, Wayne can now become an emblem of fear. Following his own ideals, Wayne splits from his mentor Ducard, and returns to Gotham to become its protector.

Like most comic book characters, Batman is malleable according to his writers and editors; he changes along with the era’s political climate to reflect or deflect social concerns. During post-WWII positivism and existing all through the 1960s, the hero’s grim city and tragic past were replaced with a lighthearted, juvenile air of escapist children’s entertainment. Laden with cartoonish plotlines and homoerotic subtexts, this version of the hero later furnished the live-action television show Batman, a camp classic of the 1960s starring Adam West. Crucial to defining the modern Batman persona, including his looming past and lasting obsessions, Frank Miller’s Year One storyline retold the hero’s origins on the comic page in 1987. Miller strengthens the rapport between a just-learning Batman and Lieutenant James Gordon, which blossoms to save a corrupt city from falling apart, requiring two honest men to stand for whatever hope remains. Gordon struggles to persevere over the bureaucracy of Gotham’s crooked elite; Batman steps over boundaries where his official counterpart must halt. In lieu of earlier BAM and KAPOW tactics purveyed by the ‘60s TV show, Miller’s storyline acculturates Batman with characteristics of film noir and other gritty crime yarns, placing his continuity inside an asphalt jungle of untamable vice, rather than a comic book world of fantastical supervillains and plotlines beyond belief. From Miller’s pointedly dour, realist tone, Nolan etched his foundation, erasing any memory of previous cinematic attempts at DC’s character.

Like most comic book characters, Batman is malleable according to his writers and editors; he changes along with the era’s political climate to reflect or deflect social concerns. During post-WWII positivism and existing all through the 1960s, the hero’s grim city and tragic past were replaced with a lighthearted, juvenile air of escapist children’s entertainment. Laden with cartoonish plotlines and homoerotic subtexts, this version of the hero later furnished the live-action television show Batman, a camp classic of the 1960s starring Adam West. Crucial to defining the modern Batman persona, including his looming past and lasting obsessions, Frank Miller’s Year One storyline retold the hero’s origins on the comic page in 1987. Miller strengthens the rapport between a just-learning Batman and Lieutenant James Gordon, which blossoms to save a corrupt city from falling apart, requiring two honest men to stand for whatever hope remains. Gordon struggles to persevere over the bureaucracy of Gotham’s crooked elite; Batman steps over boundaries where his official counterpart must halt. In lieu of earlier BAM and KAPOW tactics purveyed by the ‘60s TV show, Miller’s storyline acculturates Batman with characteristics of film noir and other gritty crime yarns, placing his continuity inside an asphalt jungle of untamable vice, rather than a comic book world of fantastical supervillains and plotlines beyond belief. From Miller’s pointedly dour, realist tone, Nolan etched his foundation, erasing any memory of previous cinematic attempts at DC’s character.

Hundreds of millions in revenue notwithstanding, Warner Bros. produced four films and four resultant artistic disappointments that failed to penetrate the Batman story’s potentially vast personal drama; instead, each seems preoccupied with design and style: In 1989, Tim Burton filmed Batman, a movie that feels hollow and dated by an awkward soundtrack by Prince, a near-useless Commissioner Gordon, and Jack Nicholson playing himself decorated as the Joker. But its success inspired 1992’s improved (and sexually charged) sequel Batman Returns, which fosters the childhood wounds of Danny DeVito’s The Penguin more than its hero’s, and a sexy Catwoman courtesy of Michelle Pfeiffer. From there, director Joel Schumacher took over the franchise, returning in 1995 with Batman Forever to a child-friendly tone reminiscent of the ‘60s show. Saturating every moment with neon and alternative music for the MTV generation, Schumacher’s first crack at Batman is colorful but brainless, his interpretations of Riddler and Two-Face laughably out of character, if not (insultingly) likened to the Joker. Beating the franchise nearly to death was Batman & Robin in 1997, Schumacher’s stupid, overstuffed farce packed with far too many characters, cheeky puns, and Hollywood names. Almost everyone involved, including Schumacher and star George Clooney, now admit fault for nearly collapsing the franchise with their living cartoon, initiating an eight-year coma for Batman on the silver screen. Warner Bros. hired writer after writer for potential franchise relaunches; among them an adaptation of Miller’s Year One directed by Darren Aronofsky and Batman vs. Superman by Wolfgang Petersen. None came to fruition.

And yet, throughout the mid-1990s, Warner Bros. Animation had already discovered the ideal Batman interpretation, in a combination of noirish storytelling and entertainment suitable for older youngsters and adults. Batman: The Animated Series (1992-1995) achieved the tone sought on the comic page, using an innovative animation style that built up from black backgrounds to furnish Batman’s world with an appropriately gothic demeanor. Created by Bruce Timm, the Emmy Award-winning show features an Art Deco-fuelled 1940s stylization, writing certainly more adult and less pun-reliant than the live-action Batman films, and orchestral music punctuating each character. Timm and collaborator Paul Dini’s time at Warner Bros. Animation generated an artistic canon for DC Comics’ hero mythologies, including the Superman and Justice League cartoons, and until Batman Begins, their show’s efforts resulted in the best filmic representation yet of the Caped Crusader—the theatrically released animated movie Batman: Mask of the Phantasm. Refurbishing characters and creating all new ones, their work was so heavily lauded that even the comics followed their call for a more severe take on the legend, instilling their innovations as Batman’s ultimate mythology.

And yet, throughout the mid-1990s, Warner Bros. Animation had already discovered the ideal Batman interpretation, in a combination of noirish storytelling and entertainment suitable for older youngsters and adults. Batman: The Animated Series (1992-1995) achieved the tone sought on the comic page, using an innovative animation style that built up from black backgrounds to furnish Batman’s world with an appropriately gothic demeanor. Created by Bruce Timm, the Emmy Award-winning show features an Art Deco-fuelled 1940s stylization, writing certainly more adult and less pun-reliant than the live-action Batman films, and orchestral music punctuating each character. Timm and collaborator Paul Dini’s time at Warner Bros. Animation generated an artistic canon for DC Comics’ hero mythologies, including the Superman and Justice League cartoons, and until Batman Begins, their show’s efforts resulted in the best filmic representation yet of the Caped Crusader—the theatrically released animated movie Batman: Mask of the Phantasm. Refurbishing characters and creating all new ones, their work was so heavily lauded that even the comics followed their call for a more severe take on the legend, instilling their innovations as Batman’s ultimate mythology.

While Batman Begins has received much praise for its realistic approach to the superhero’s birth, this supposed “realism” exists above all in its emotional treatment of Wayne and his clumsy growth into Batman. The film is about a man dressed up as a bat, after all. Nolan’s construction of Batman’s arsenal of gadgets and weapons comes without the polish of previous films, most deriving from abandoned prototypes by Wayne Enterprises’ Applied Sciences Division: his Batmobile was made to assemble bridges; his impenetrable Nomex suit was intended for military body armor; his cape lightweight “memory cloth” that hardens for gliding-flight during parachute drops—all reformatted from practical items, versus the hero inexplicably constructing futurist gizmos from scratch (and thus, finally responding to that long-unanswered question, “Where does he get those wonderful toys?”). Even the Batcave remains just a cavern, to be redecorated in future sequels. His first forays into Gotham City are not without punishing results, leaving him bruised and burned from the learning process. The painful and human reality of his night stalking physically marked, audiences see Batman’s fear-inducing presentation evolve; as a result, we are so much more involved when his theatricality succeeds and sends criminals screaming into the night.

Rather than pit our hero against his most commonly known archnemesis The Joker, or any other of the colorful antagonists painted with comic strokes over the years, the chosen villains, conceptualized without flashy and polished getups, personify Batman’s varied emotional conflicts and themes, all arranged to form what becomes a single criminal scheme. And unlike previous entries in the franchise, the result does not overwhelm since the villains, however numerous, represent stages of our hero’s psychological growth: Signifying Gotham’s criminal underworld, thus a figurative link to the murder of Bruce Wayne’s parents, mob boss Carmine Falcone (Tom Wilkinson) imports drugs into the urban sprawl, among them hallucinogens for Dr. Jonathan Crane (Cillian Murphy). Also known as Scarecrow, Crane, Arkham Asylum’s psychopharmacologist, mirrors Batman’s vulnerability to and exploitation of fear. Manipulating fear as his greatest weapon, Scarecrow studies the effects of fear on his patients to disturbing extremes. He implements a scheme, sponsored by the League of Shadows, to release his fear toxin into Gotham on a massive scale, which will send the population into panic and bring down the city as Ra’s al Ghul intended. By stopping this trifecta of villains, Wayne confronts the underworld that murdered his parents, prevails over his surrender to fear, and establishes himself as the guardian of Gotham City.

Rather than pit our hero against his most commonly known archnemesis The Joker, or any other of the colorful antagonists painted with comic strokes over the years, the chosen villains, conceptualized without flashy and polished getups, personify Batman’s varied emotional conflicts and themes, all arranged to form what becomes a single criminal scheme. And unlike previous entries in the franchise, the result does not overwhelm since the villains, however numerous, represent stages of our hero’s psychological growth: Signifying Gotham’s criminal underworld, thus a figurative link to the murder of Bruce Wayne’s parents, mob boss Carmine Falcone (Tom Wilkinson) imports drugs into the urban sprawl, among them hallucinogens for Dr. Jonathan Crane (Cillian Murphy). Also known as Scarecrow, Crane, Arkham Asylum’s psychopharmacologist, mirrors Batman’s vulnerability to and exploitation of fear. Manipulating fear as his greatest weapon, Scarecrow studies the effects of fear on his patients to disturbing extremes. He implements a scheme, sponsored by the League of Shadows, to release his fear toxin into Gotham on a massive scale, which will send the population into panic and bring down the city as Ra’s al Ghul intended. By stopping this trifecta of villains, Wayne confronts the underworld that murdered his parents, prevails over his surrender to fear, and establishes himself as the guardian of Gotham City.

Instilling substance in every performance, Nolan’s cast was chosen not by their celebrity, rather for their abilities to epitomize classic characters. Bale’s performance pivots Wayne on the actor’s undeniable ability to evoke the character’s brooding disposition, handled with genuineness and severity by a performer gradually becoming one of Hollywood’s most respectable figures. Michael Caine decorates his lines as Alfred with appropriate humor and wisdom, servicing the film and, indeed, his character with limitless supplies of conscience and heart. And Gary Oldman seems to embody the very essence of the James Gordon from Miller’s text and Timm’s cartoon, both in appearance and spirit. The combined presence of the cast—including names like Liam Neeson, Tom Wilkinson, Cillian Murphy, Morgan Freeman, Rutger Hauer, and Katie Holmes—brings an unprecedented, unexpected integrity to what might have been a mere comic book movie.

Batman Begins not only starts a landmark franchise, but it also reestablishes an ongoing mythology that, in film, was close to crumbling, sustaining its frames with drama that far surpasses the usual overtly commercial popcorn-munching fare of the genre. Nolan’s reinvention of the series disregards Burton and Schumacher’s now altogether eclipsed efforts, starting afresh in the grave traditions of Miller and Timm. The film extends adult themes into realms of tragedy, and therein births a new height for the genre. Whereas Hollywood often consumes and spews out superhero franchises like bubblegum unworthy of consideration, several properties have taken a hint from Nolan’s film, underlining darker, dramatic, and realist aspects of their characters’ psychology to elevate the filmic story into cinematic art, deepening their description beyond just brave symbols and into relatable individuals retaining emotional pull. As a result, the concept of “mere comic book movie” has almost evaporated since the release of Nolan’s dark opus, inciting a singular comic-to-film renaissance that has since established the genre’s authority.

Batman Begins not only starts a landmark franchise, but it also reestablishes an ongoing mythology that, in film, was close to crumbling, sustaining its frames with drama that far surpasses the usual overtly commercial popcorn-munching fare of the genre. Nolan’s reinvention of the series disregards Burton and Schumacher’s now altogether eclipsed efforts, starting afresh in the grave traditions of Miller and Timm. The film extends adult themes into realms of tragedy, and therein births a new height for the genre. Whereas Hollywood often consumes and spews out superhero franchises like bubblegum unworthy of consideration, several properties have taken a hint from Nolan’s film, underlining darker, dramatic, and realist aspects of their characters’ psychology to elevate the filmic story into cinematic art, deepening their description beyond just brave symbols and into relatable individuals retaining emotional pull. As a result, the concept of “mere comic book movie” has almost evaporated since the release of Nolan’s dark opus, inciting a singular comic-to-film renaissance that has since established the genre’s authority.

When treated with the lofty ambitions Nolan sets down here, though rare, the comic book film can become high cinematic art. Batman Begins is the launching pad for that movement, although no other filmmaker—outside of Nolan himself—has outdone what he achieved here. Nolan does so by combining his technical mastery with his gift for supplying narrative rich with symbolic storytelling. The themes running through the film create a character whose origins seek to discover what it means to be a superhero, but also what it takes for “just a man” to become a superhero. From his self-imposed moral guidelines, a human being becomes an emblem from which an entire city draws the will to change and force out injustice. In doing so, the figurehead of Batman emphasizes a basic human need for symbols, while Batman Begins explores that theme in a thoughtful, exciting, expertly made motion-picture.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review