The Definitives

Barry Lyndon (1975)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

A sprawling period piece of immaculate design and elusive temper, Barry Lyndon might contain the narrative elements and setting of a grand historical drama or epic romance, but Stanley Kubrick’s film could never be attributed to such conventional modes of filmmaking. William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon, published in monthly magazine installments, tells Redmond Barry’s picaresque life story in a first-person account. Often cited as the first novel ever written without a hero, it follows a scoundrel who strives to become a gentleman. Thackeray’s description of Barry Lyndon is that of a narcissistic and disreputable opportunist, shameless and without standard descriptions of redemptive promise. Drawn to oblique conceits of this kind, Kubrick reshaped the material into a third-person account of Barry’s life-to-death saga, his seemingly omniscient narrator looking down upon an amoral character of modest lineage determined to better his betters. Then, the director incorporates impressive historical detail and pageantry wherein the sheer sumptuousness overshadows his restrained, certainly detached treatment of the characters. Through it all, Kubrick challenges us to identify with Barry, though the character’s world and Kubrick’s methods of storytelling do not.

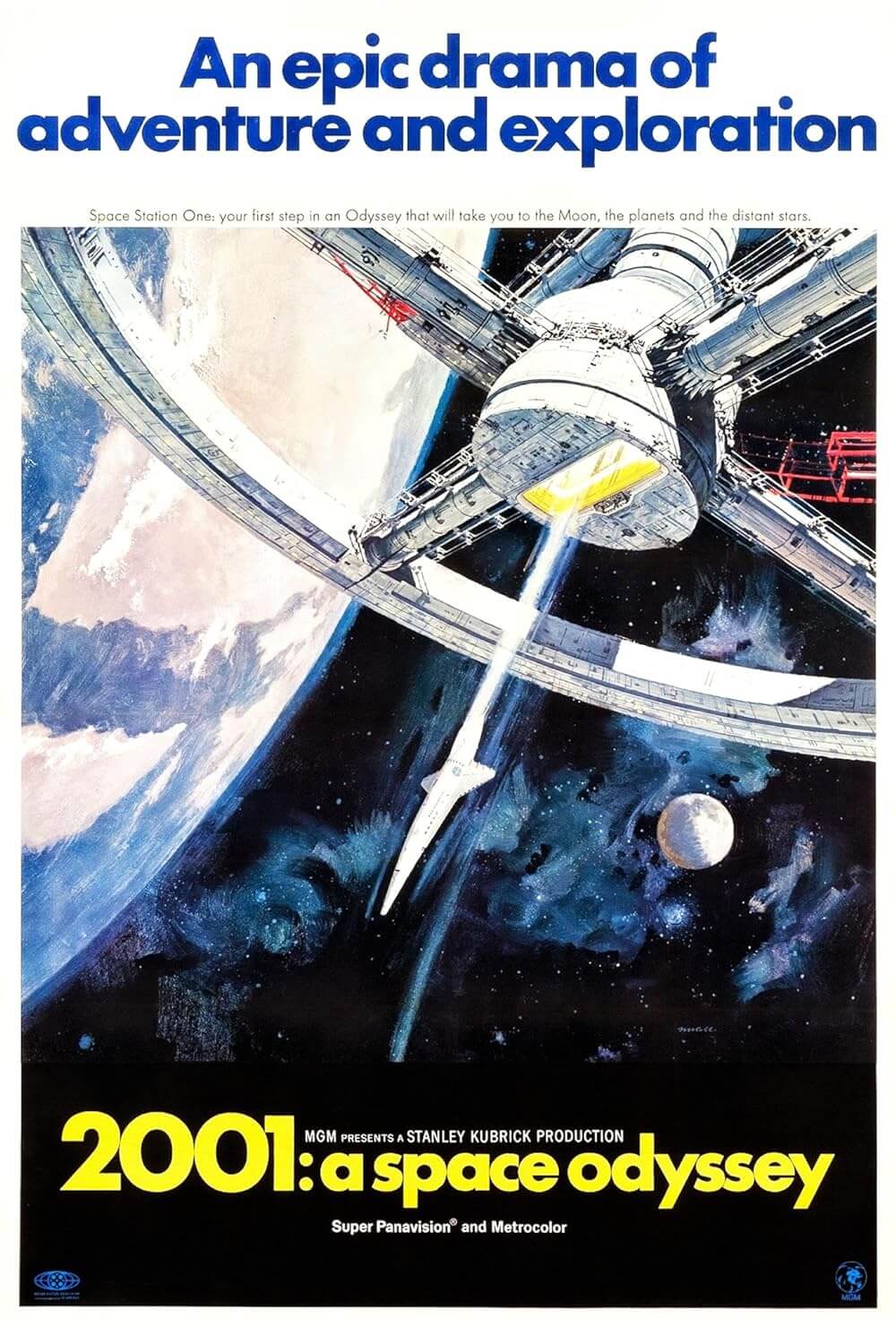

Of all Kubrick’s films, time and again pigeonholed as being emotionally distant—from the vast impenetrability of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) to the violent comedy of A Clockwork Orange (1971) to the intimate sexual confrontation that is Eyes Wide Shut (1999)—Barry Lyndon represents the director’s greatest test of his audience. Released in 1975 to indifference given its outward sense of coldness toward its subject, the film demands an audience see beyond its luscious application of costumed pageantry and opulent décor, even beyond the narrator’s assessments, and recognize our all-too-common incapacity to relate to another human being because of appearances or class. Kubrick asks that we ignore the classical forms of storytelling employed and follow our natural instincts as moviegoers that insist we find some way to relate. What an obstacle course he has set for his viewers, his picture ensnared in the vanity of Barry Lyndon’s desire. Evident in every frame, Kubrick has reconstructed a regal 18th century world with meticulous detail to such a degree that his supreme attention to historical objectivity has been accused of removing the film’s humanity; just as how, through a superior narrator who seems to have contempt for Barry, Kubrick brings into question and the entire notion of authorship. In turn, Kubrick asks that we peer through such artifice to make our own assessments.

Leisurely paced for over three hours and two acts, Kubrick’s film renders every moment necessary and immediate to the description of his eponymous character. The film’s events follow an Irish lad born to a modest family in the mid-18th century. After a fateful duel for unrequited love, Redmond Barry (Ryan O’Neal) enlists in the British army, fights in the Seven Years’ War, and in time deserts his post. Confronted by Prussians, he joins up and becomes a good soldier only to desert once more, this time to join a chic card sharp he was assigned to spy on—the Chevalier de Balibari (Patrick Magee), a con man with whom Barry aligns for months of scheming exploits throughout Europe. They are exposed following accusations of deception and retreat to France, where Barry patiently waits for the dying husband of the wealthy Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson) to pass. He and Lady Lyndon eventually marry and the now-named Barry Lyndon spends his wife’s fortune without restraint, earning a reputation of some stature for himself, all the while quarreling with his new stepson, Lord Bullingdon (Leon Vitali). The couple has a child together; though, because Barry has no title, neither he nor his son would be allowed access to the Lyndon fortune should Lady Lyndon die. For this, Barry aspires to earn a title, but his ongoing clash with Lord Bullingdon leads to a scandalous public display that sours his chances. After his son tragically dies in a horse-riding accident, Barry is confronted by Bullingdon in a duel, in which Barry loses a leg and his claim to the Lyndon fortune. In the end, the hero’s unchecked ambitions become his undoing; he is left alone and broke, beset by family tragedy. The film’s narrator explains that Barry’s remaining years are suspect; he’s thought to have traveled to the New World, where he resumes his gambling exploits to no avail.

Leisurely paced for over three hours and two acts, Kubrick’s film renders every moment necessary and immediate to the description of his eponymous character. The film’s events follow an Irish lad born to a modest family in the mid-18th century. After a fateful duel for unrequited love, Redmond Barry (Ryan O’Neal) enlists in the British army, fights in the Seven Years’ War, and in time deserts his post. Confronted by Prussians, he joins up and becomes a good soldier only to desert once more, this time to join a chic card sharp he was assigned to spy on—the Chevalier de Balibari (Patrick Magee), a con man with whom Barry aligns for months of scheming exploits throughout Europe. They are exposed following accusations of deception and retreat to France, where Barry patiently waits for the dying husband of the wealthy Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson) to pass. He and Lady Lyndon eventually marry and the now-named Barry Lyndon spends his wife’s fortune without restraint, earning a reputation of some stature for himself, all the while quarreling with his new stepson, Lord Bullingdon (Leon Vitali). The couple has a child together; though, because Barry has no title, neither he nor his son would be allowed access to the Lyndon fortune should Lady Lyndon die. For this, Barry aspires to earn a title, but his ongoing clash with Lord Bullingdon leads to a scandalous public display that sours his chances. After his son tragically dies in a horse-riding accident, Barry is confronted by Bullingdon in a duel, in which Barry loses a leg and his claim to the Lyndon fortune. In the end, the hero’s unchecked ambitions become his undoing; he is left alone and broke, beset by family tragedy. The film’s narrator explains that Barry’s remaining years are suspect; he’s thought to have traveled to the New World, where he resumes his gambling exploits to no avail.

After completing 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick originally planned to make Napoleon, an expensive historical epic on which MGM pulled the plug after the box-office flop of Dino De Laurentiis’ similar Waterloo in 1970. The ever-meticulous Kubrick identified with Napoleon’s logistical way of thinking, Napoleon being an emperor who oversaw his realm with the same organizational obsession that Kubrick famously applied to his film projects. Kubrick long considered Napoleon a kind of unrealized destiny, but moved on nonetheless to make A Clockwork Orange, a film set to the music of Beethoven, whose compositions inspired Napoleon’s domination of Europe. After the debut of A Clockwork Orange, strident anti-violence campaigners, chiefly in Britain where Kubrick called home, began to include Kubrick’s latest with a number of recent films (among them Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs) that tested the limits of screen censorship. Kubrick recoiled from these reactions despite the film’s success internationally, and in turn he began to show the first major signs of his famous withdrawal from public view. Perhaps in response to his failure to launch Napoleon and the reactions to A Clockwork Orange, the director settled on Thackeray’s novel for his next project. Its backdrop of the Seven Years’ War contained many similar European vistas and military situations he might have used in Napoleon, whereas he could explore subject matter that once again demanded viewers look past the surface of the narrative, as so many had failed to do with A Clockwork Orange.

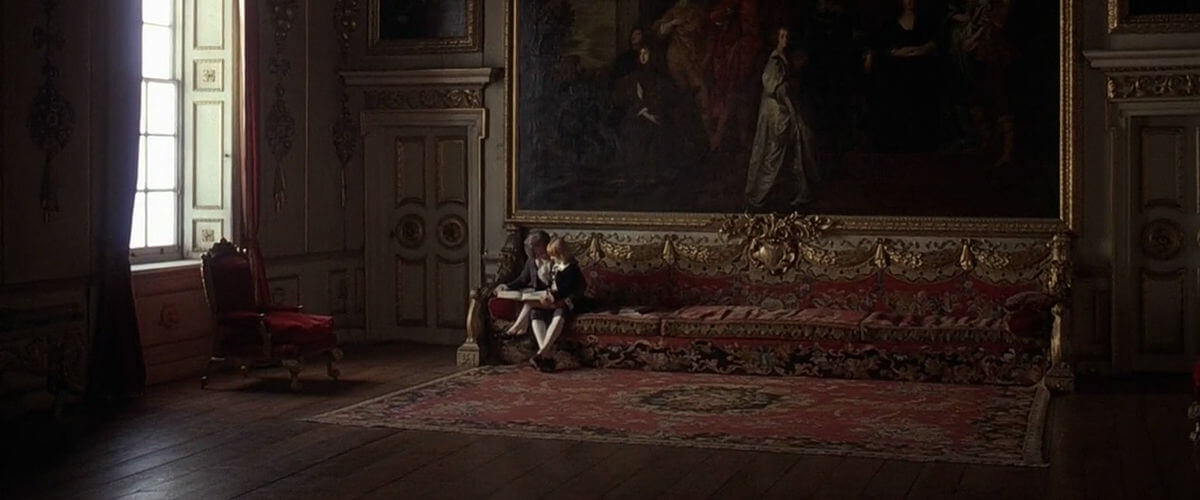

Shot over 300 days in Ireland, England, and some exteriors in Germany, Kubrick would make just as many daring technical choices on Barry Lyndon as he did when representing space and beyond in 2001: A Space Odyssey, although few were so evident as a fantastical Monolith or Star Child. Foremost is the work of cinematographer John Alcott, who won an Oscar for his gorgeous use of natural lighting. Relying on authentic light and minimal electric sources, Alcott painstakingly lit scenes by natural light or candlelight, using special lenses designed by NASA for low-light shooting on moon landings. Push processing film stock allowed overexposures to bring up dim scenes, lending the image a glow that by design resembled stately 18th century paintings by the likes of Thomas Gainsborough and William Hogarth. Art directors Ken Adam, Roy Walker, and Vernon Dixon, also Oscar winners for their work on the film, researched European estates from the period and when possible Kubrick shot on actual locations. Oscar-winning costumes by Ulla-Britt Söderlund and Milena Canonero adhered with jealous devotion to the period’s styles, while scorer Leonard Rosenman, another of the film’s Oscar winners, used works from Mozart, Bach, Schubert, and notably Handel in his orchestral compositions under Kubrick’s close instruction. What must be one of the most beautiful films ever made, the production’s extravagance is awe-inspiring and intentionally dwarfs the inexpressive characters who occupy it, implying a surface-level notion wherein one individual remains insignificant within a greater historical context.

Additionally, Kubrick instills thoughtful distance as we examine the period details and historical flourishes ornamenting his painterly compositions. Nearly every shot is framed like an 18th-century painting: from far away, the characters but meager components within the larger scene. Like figures in a painting, his characters are shown as though Kubrick sees his audience as patrons of an art museum forced to keep a distance from the works on exhibition. The opening image is of Barry’s father shot to death in a duel, and Kubrick’s large frame renders the characters into specks within a larger expanse; such acts become rituals within themselves, the characters like animated oil on canvas, compelled to move by some sagacious brushstrokes. A recurring visual motif finds the camera pulling back from a single point in a tight frame to reveal all of the scholarly historical detail Kubrick and his crew have incorporated into the shot. Close-ups for their own sake are rare in Barry Lyndon, since they would presuppose the importance of the given character. More prominent is the sense of majestic history: the manners, rich costumes, social formalities, military formations, verbal inflections, and overall historical life pumped into the production. Appreciating these qualities aligns us with Kubrick himself, whose fascination with history seeks to recreate every extravagant detail here to magnificent effect. And yet, to be totally consumed by such historical objectivity is to fail Kubrick’s call for sophisticated viewership.

Additionally, Kubrick instills thoughtful distance as we examine the period details and historical flourishes ornamenting his painterly compositions. Nearly every shot is framed like an 18th-century painting: from far away, the characters but meager components within the larger scene. Like figures in a painting, his characters are shown as though Kubrick sees his audience as patrons of an art museum forced to keep a distance from the works on exhibition. The opening image is of Barry’s father shot to death in a duel, and Kubrick’s large frame renders the characters into specks within a larger expanse; such acts become rituals within themselves, the characters like animated oil on canvas, compelled to move by some sagacious brushstrokes. A recurring visual motif finds the camera pulling back from a single point in a tight frame to reveal all of the scholarly historical detail Kubrick and his crew have incorporated into the shot. Close-ups for their own sake are rare in Barry Lyndon, since they would presuppose the importance of the given character. More prominent is the sense of majestic history: the manners, rich costumes, social formalities, military formations, verbal inflections, and overall historical life pumped into the production. Appreciating these qualities aligns us with Kubrick himself, whose fascination with history seeks to recreate every extravagant detail here to magnificent effect. And yet, to be totally consumed by such historical objectivity is to fail Kubrick’s call for sophisticated viewership.

In adapting a rather scholarly and under-read novel, Kubrick could be far more liberal than with the historical details of his production, as Thackeray’s text had not been widely known to the public. His broad liberties with the source would go mostly unnoticed by general audiences, unlike those he made on Lolita (1962) and A Clockwork Orange that were rebuked by devoted readers of Vladimir Nabokov and Anthony Burgess. Rather than tell the story from Barry’s perspective, thus aligning us with the desires of the protagonist as Thackeray’s novel does, Kubrick transformed the story by transferring the narration to an unseen speaker who plays no role in Barry’s tale. Thackeray’s use of the first-person narrator forces the reader to sympathize with Barry’s life story as he tells it, and therefore his version of Barry is far more boldly malicious. Kubrick isn’t so obvious; he removes this pretense by eliminating the manipulation involved in a first-person account. Unlike most conventional films, the story is expounded in a series of anticlimactic developments in Barry’s life, none of which contain suspense or surprise in their dramatic turns because the narrator has prepared us for them. Voiced by Michael Hordern, the narrator explains what occurs onscreen as we see it, and often before we see it. Thus, Kubrick turns his viewers into an audience of onlookers as opposed to the long-desired cinematic ideal of participants.

Kubrick’s seemingly all-knowing narrator supplies the audience with some historical information and what would seem to be objective commentary. But looking closely, what we see often does not align with the narrator’s assessments. The narrator occupies a position of subjectivity: he makes assumptions, passes judgment, and remains a propagandist of sorts, his disdain for Barry’s lifestyle evident in his inflections. He seems to agree with Lord Bullingdon that Barry is a “common opportunist” and as such the narrator occupies a position of hierarchal superiority from which he looks down upon the story’s protagonist. His evaluation of Barry’s motivations is based on surfaces and his knowledge of the events in the hero’s life, as opposed to true transcendent omniscience—such as knowing Barry’s motivations because, like an author, he can see inside the hero’s mind. Supplying the broad-strokes of the story, the narrator might sway our own conclusions about Barry, as Kubrick’s image does not provide a drastic contrast to the voiceover, but rather a neutral ground on which multiple pronouncements could be made. In an interlude after Barry’s desertion from the British army, he finds comfort with a German woman whose husband is off to war; the narrator fails to see what we do—the quite intimate romance behind this scene—and instead suggests Barry has fallen for a whore, though our hero does not seem to know or care. Barry shares much tenderness with the woman. Furthermore, the narrator uses phrases such as “appears to have” that suggest he has engaged in hearsay or conjecture, and therefore in his admittance of uncertainty, he discloses how his own suppositions have been placed into his account of Barry’s story. The narrator is the kind of unsophisticated observer Kubrick rallies against and hopes his filmgoing audience is better than.

Kubrick’s famous emotional distance furnishes a cast of cold actors who seem chosen for their look more than their range as performers. For example, he requires little from Marisa Berenson, a former model whose onscreen presence is limited to remote expressions and the occasional beam or expression of grief. In one scene, perhaps the most unsettling demonstration of Barry’s pride, he blows pipe smoke into Lady Lyndon’s face after she asks him to stop smoking. Statuesque, she does not react despite her position over her new husband; rather, she accepts the smoke as she accepts almost all else in the film, with a degree of stoic elegance. Kubrick fashions Barry as the most expressive character in a film where society is represented as reserved and mannered, just as HAL-9000 was the liveliest character amid the orderly and dryly scientific humans of 2001: A Space Odyssey. In both films, Kubrick maintains a kind of sympathy for creatures who struggle to survive. Barry’s narrator and his betters may label him an opportunist; his Prussian superior remarks, “For all your talents and bravery, I am sure you will come to no good.” But Kubrick implies that we must watch without prejudice, particularly in his Epilogue, which is not spoken by the narrator but displayed by the director as his last word on Barry Lyndon: “It was in the reign of King George III that the aforesaid personages lived and quarreled; good or bad, handsome or ugly, rich or poor, they are all equal now.”

Kubrick’s famous emotional distance furnishes a cast of cold actors who seem chosen for their look more than their range as performers. For example, he requires little from Marisa Berenson, a former model whose onscreen presence is limited to remote expressions and the occasional beam or expression of grief. In one scene, perhaps the most unsettling demonstration of Barry’s pride, he blows pipe smoke into Lady Lyndon’s face after she asks him to stop smoking. Statuesque, she does not react despite her position over her new husband; rather, she accepts the smoke as she accepts almost all else in the film, with a degree of stoic elegance. Kubrick fashions Barry as the most expressive character in a film where society is represented as reserved and mannered, just as HAL-9000 was the liveliest character amid the orderly and dryly scientific humans of 2001: A Space Odyssey. In both films, Kubrick maintains a kind of sympathy for creatures who struggle to survive. Barry’s narrator and his betters may label him an opportunist; his Prussian superior remarks, “For all your talents and bravery, I am sure you will come to no good.” But Kubrick implies that we must watch without prejudice, particularly in his Epilogue, which is not spoken by the narrator but displayed by the director as his last word on Barry Lyndon: “It was in the reign of King George III that the aforesaid personages lived and quarreled; good or bad, handsome or ugly, rich or poor, they are all equal now.”

With the successes Love Story (1970) and Paper Moon (1973) to his name, Ryan O’Neal was a major star in the 1970s and represented an unlikely casting choice for Kubrick. For Warner Bros., the bankable actor warranted the director’s then-pricey $11 million budget, but Kubrick’s use of him results in anything but a traditional Hollywood leading man role. O’Neal has no grand speeches or typical standout actor’s moments; he occupies the screen with deliberate passivity and a sort of ache behind his eyes to which the viewer must assign meaning. Any ambition that O’Neal may have had to distinguish himself in Barry Lyndon is undone by Kubrick intentionally pinning back the emotional expressiveness of the main character. As suggested, this is even truer with the rest of Kubrick’s cast, employed primarily for their faces and screen presence. Kubrick requires little more of O’Neal beyond his being there; however distressing this may have been for O’Neal the ambitious young actor, the performance becomes a part of Kubrick’s highly integrated mise-en-scène. At times, O’Neal serves as a mere instrument, arguably exploited for his celebrity and muted to extremes, and is made over into an externally affectless set piece that becomes a part of his larger, showy surroundings. In other scenes, Barry sobs over a tragic death or loses his temper in violent outbursts, but more often than not he simply reacts to the world around him. Unlike Thackeray’s description of Barry as a scheming rogue actively chasing his betterment, Kubrick’s version depicts the character as an inert subject to whom things happen.

Consider the scene where Barry’s cousin and first love, Nora Brady (Gay Hamilton), hides a ribbon in her bodice and tells him, “I will think very little of you if you do not find it.” Young and reticent, he knows where she’s hidden it but refuses the plunge until she guides his trembling hand onto her breast. If Barry had been a pure opportunist, this would be his moment; but instead, he quivers and disguises his pleasure. This is not to suggest Barry is without desire. Only under moments of extreme duress does Kubrick’s version of Barry break this passive pattern, a quality which counteracts the narrator’s estimation of him. When Nora betrays him for well-to-do English Captain John Quin (Leonard Rossiter), Barry throws a glass of wine in the man’s face and bravely risks his life in a duel for honor, and he wins. His passionate actions are later negated when, after joining the British army, Barry’s fatherly second Captain Grogan (Godfrey Quigley) reveals the Brady family staged the cowardly Quin’s death to benefit from Nora and Quin’s eventual union. Over and over, Barry’s modest victories and displays of emotions have unfortunate consequences, as keeping one’s composure no matter the situation was a sign of distinction and class, whereas showing emotion remained relegated to peasant classes. It is this persistent dramatic motif that makes the film a kind of tragedy.

In the first scene of Barry Lyndon, where Barry’s father dies in a duel when Barry was just a boy, Kubrick establishes the theme of absent fathers. Barry’s ongoing search for a father-figure becomes one of the film’s most prominent underlying themes in the first half, even if in results in a procession of disappointments and failures. Until he becomes a father himself, Barry looks up to father-figures who have determining roles in his life: the death of Captain Grogan incites Barry to desert; he becomes a good soldier for his Prussian master Captain Potzdorf (Hardy Krüger); Chevalier de Balibari schools him in criminal exploits. A boy ever-searching for a father, Barry’s seems to hit upon his ideal father early in the picture. Forced to leave home for Dublin after he purportedly kills Quin, Barry finds himself at gunpoint by a pair of robbers, the famous highwayman Captain Feeney (Arthur O’Sullivan) and his son. Not a scene in Thackeray’s novel, Kubrick uses this moment to illustrate the kind of relationship Barry aspires to share with a father-figure, represented by Feeney, whose son has joined him in the “family trade”. Rather than a cold-blooded opportunist, then, Barry is willing to take any steps necessary to fulfill his desperate need for a father. Later, overcome by this yearning when he meets the Chevalier, whose origin as an excised Irishman affords a unique closeness and sense of home for Barry, he confesses that he was sent by Captain Potzdorf as a spy, but realigns his loyalties for his final father-figure. At Barry’s confession, the Chevalier rises from his chair and embraces his fellow Irishman with the tenderness Barry has searched for throughout Act I, called By What Means Redmond Barry Acquired the Style and Title of Barry Lyndon.

In the first scene of Barry Lyndon, where Barry’s father dies in a duel when Barry was just a boy, Kubrick establishes the theme of absent fathers. Barry’s ongoing search for a father-figure becomes one of the film’s most prominent underlying themes in the first half, even if in results in a procession of disappointments and failures. Until he becomes a father himself, Barry looks up to father-figures who have determining roles in his life: the death of Captain Grogan incites Barry to desert; he becomes a good soldier for his Prussian master Captain Potzdorf (Hardy Krüger); Chevalier de Balibari schools him in criminal exploits. A boy ever-searching for a father, Barry’s seems to hit upon his ideal father early in the picture. Forced to leave home for Dublin after he purportedly kills Quin, Barry finds himself at gunpoint by a pair of robbers, the famous highwayman Captain Feeney (Arthur O’Sullivan) and his son. Not a scene in Thackeray’s novel, Kubrick uses this moment to illustrate the kind of relationship Barry aspires to share with a father-figure, represented by Feeney, whose son has joined him in the “family trade”. Rather than a cold-blooded opportunist, then, Barry is willing to take any steps necessary to fulfill his desperate need for a father. Later, overcome by this yearning when he meets the Chevalier, whose origin as an excised Irishman affords a unique closeness and sense of home for Barry, he confesses that he was sent by Captain Potzdorf as a spy, but realigns his loyalties for his final father-figure. At Barry’s confession, the Chevalier rises from his chair and embraces his fellow Irishman with the tenderness Barry has searched for throughout Act I, called By What Means Redmond Barry Acquired the Style and Title of Barry Lyndon.

In Act II, Containing an Account of the Misfortunes and Disasters Which Befell Barry Lyndon, the film’s structure shifts from a sweeping journey across Europe to a chamber drama of lavishly decorated salons, bedrooms, dining halls, and gardens on the Lyndon estate. Barry’s search for a father subsides as he becomes a husband to Lady Lyndon and failed stepfather to the unresponsive and contemptuous Lord Bullingdon. Although Bullingdon rejects his new stepfather, even the narrator admits that Barry is a loving parent to his son, Bryan (David Morley). But with Bryan’s death, Barry, robbed of his chance to become like Captain Feeney, falls into an unrecoverable despair, and his past confrontations with Bullingdon resurge when his stepson returns home an adult and demands satisfaction. The protracted duel between Barry and Bullingdon, set to Handel’s “Sarabande”, unfolds at a methodical pace, recalling the execution sequence in Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957). Their pistols loaded, Bullingdon has the first shot but his gun fires into the ground by accident. In an act of fatherly mercy, Barry fires his shot into the ground as well. Had he been the malicious opportunist that Bullingdon and the narrator believe him to be, Barry would have shot the impetuous Bullingdon down to rid himself of the annoyance and secure his claim to the Lyndon fortune. But Barry’s decision to forfeit his shot secures his ruin as the callous Bullingdon fires again, this time striking his opponent in the leg which later must be amputated. The event marks Barry’s final fruitless attempt to establish a father-son relationship like the one he never had.

In the style of many a 19th-century novel, Thackeray could not recognize the basic human instinct to better oneself and instead painted his character as a rascal ironically blind to the wickedness behind his misdeeds. Kubrick understands the desire to survive and prevail by any means, and this stands as a recurring theme in his body of work. Here, the director tells Redmond Barry’s story from the perspective of formal mannerism and the pageantry of the classical elite, while his protagonist contrasts this in his quality and hopes to become all that such a position entails. An audience would seem to have no choice but to look upon Barry as a scoundrel and opportunist insolently striving for a station greater than he is worthy. But, if as suggested earlier, Barry Lyndon is a reaction to the failure of A Clockwork Orange’s detractors to see beyond the stylized violence, then Kubrick has a made a film about the ability for a piece of cinema to inhabit one mode, the author to inhabit another, while at the same time outlining the necessity for viewers to deconstruct what these perspectives infer without being told. In this sense, Kubrick champions a call for sophisticated viewing in Barry Lyndon.

A film that best defines Kubrick’s intellect, antisocial withdrawal, and obsessive tenure as a filmmaker, Barry Lyndon is also masterful, technically precise, and narratively complex. But these are words to describe every Stanley Kubrick film. And like other Kubrick films, to absorb its multifarious components in one viewing is impossible; it took film historians and critics a quarter of a century to finally reassess their initial indifference and distinguish the film as perhaps Kubrick’s most intricate and accomplished motion picture next to 2001: A Space Odyssey. Above all, the film remains Kubrick’s greatest challenge to his audience, to acknowledge the dilemma of this method and sympathize with his hero. How easily the painterly lavishness of the production, which does not serve the drama (quite the opposite), washes over the audience with a sense of awe. How carefully we must watch to set aside the period and its characters’ intolerance of our hero, and even the sensibility reserved by the narrator, to identify with Barry. When finally we see Barry Lyndon less as a restrained historical retelling of a nineteenth-century novel and more as an unconventional human tragedy that exposes the bias of history, we finally begin to see history and humanity as Kubrick does.

A film that best defines Kubrick’s intellect, antisocial withdrawal, and obsessive tenure as a filmmaker, Barry Lyndon is also masterful, technically precise, and narratively complex. But these are words to describe every Stanley Kubrick film. And like other Kubrick films, to absorb its multifarious components in one viewing is impossible; it took film historians and critics a quarter of a century to finally reassess their initial indifference and distinguish the film as perhaps Kubrick’s most intricate and accomplished motion picture next to 2001: A Space Odyssey. Above all, the film remains Kubrick’s greatest challenge to his audience, to acknowledge the dilemma of this method and sympathize with his hero. How easily the painterly lavishness of the production, which does not serve the drama (quite the opposite), washes over the audience with a sense of awe. How carefully we must watch to set aside the period and its characters’ intolerance of our hero, and even the sensibility reserved by the narrator, to identify with Barry. When finally we see Barry Lyndon less as a restrained historical retelling of a nineteenth-century novel and more as an unconventional human tragedy that exposes the bias of history, we finally begin to see history and humanity as Kubrick does.

Bibliography:

Chion, Michel. Kubrick’s Cinema Odyssey. British Film Institute, 2001.

LoBrutto, Vincent. Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. D.I. Fine Books, 1997.

Nelson, Thomas Allen. Kubrick, Inside a Film Artist’s Maze. New and expanded ed. Indiana University Press, 2000.

Sperb, Jason. The Kubrick Facade: Faces and Voices in the Films of Stanley Kubrick. Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Philips, Gene D., editor. Stanley Kubrick: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Walker, Alexander, et al. Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis. Rev. and expanded. Norton, 1999.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review