The Definitives

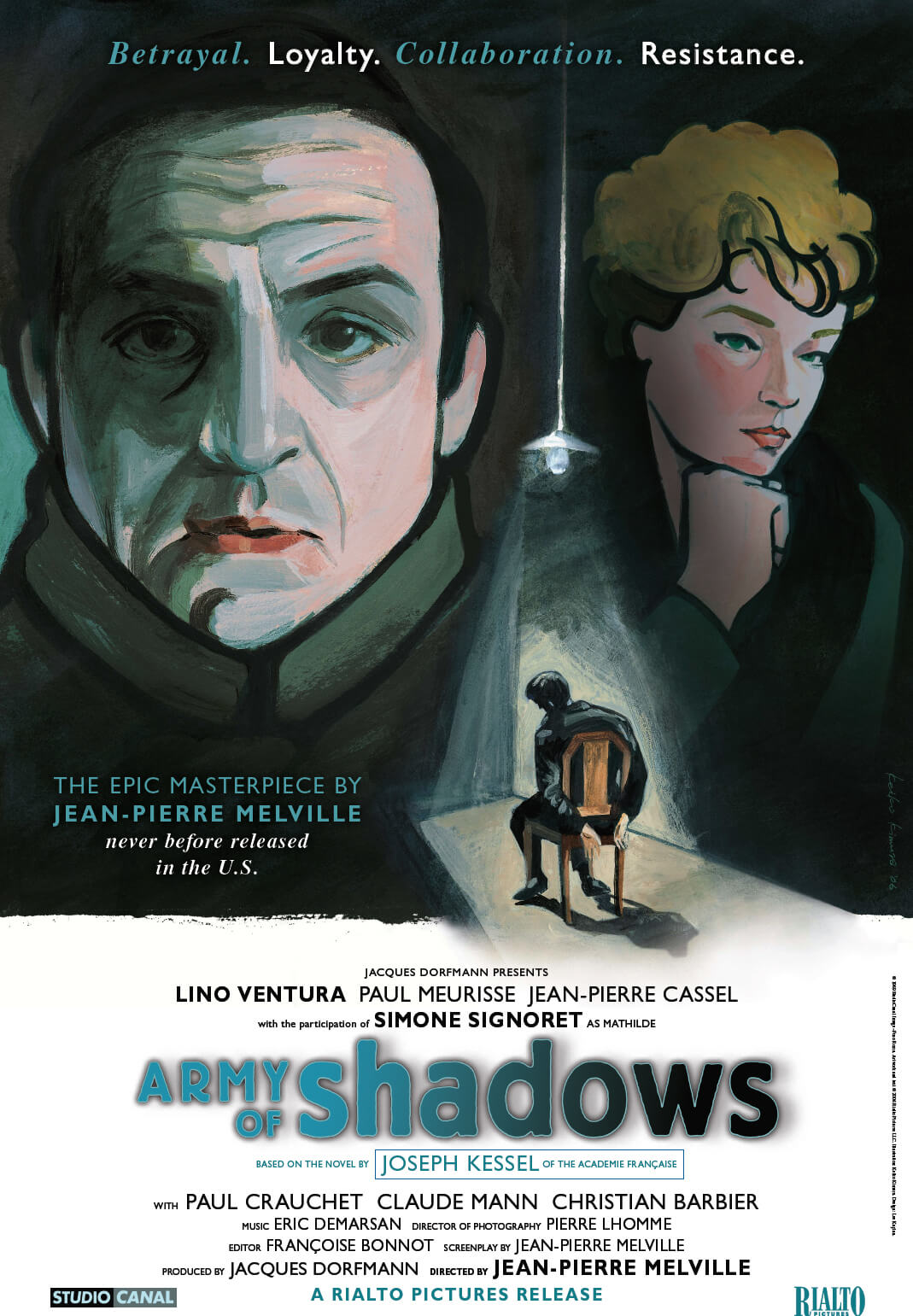

Army of Shadows (1969)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

With Vichy France under Pétain’s rule and collaborating with Nazi Germany, the French maquis operated under a veil of subterfuge, driven by uncommon patriotism. Barely visible through the thick fog of World War II history, save for an obscure profile, French Resistance guerrillas have received mostly idealized depictions in film. Though their struggle often makes for an exciting wartime yarn, in distinguishing a more true-to-spirit Resistance, without glorifying the depiction of violence, audiences have Jean-Pierre Melville’s film Army of Shadows (L’Armée des ombres). Based on the 1943 book by Belle du jour novelist Joseph Kessel, Melville wrote and filmed the picture between his more well-known Le samouraï (1967) and Le Cercle rouge (1970). The director steps out of his skin as the réalisateur of cool crime pictures—a reputation well established after his 1955 masterwork, Bob le flambeur. He employs a similar mood and character types from those films, often showing members of the Resistance with a fatalistic devotion to their work, just as Melville’s Bob has for gambling, or Jef Costello has as a gun for hire. Melville’s Resistance is an inevitable pathway to death, his characters walking dutifully onward as they barely survive exposure, double-cross, or moral ambiguities intrinsic to their station. This dynamic elevates Melville’s reputation in America beyond his then-customary status as a gangster film director. In fact, if we look at his films Silence and Léon Morin, prêtre, we can see a pseudo war trilogy, unconnected but enclosed in Melville’s significant observations about World War II.

Setting the tone to Army of Shadows ahead of the opening credits, Melville shows us German soldiers marching on the Champs-Elysées. Aside from the obvious visual significance—the collective body stomping with an orderly and geometric shape, more assembled and impenetrable than a tank—Melville fought to shoot the image on location. After the First World War, any German uniform was forbidden on the Champs-Elysées. So dressing up actors (or in this case dancers, to capture the robotic movement that would enunciate the sound of the German march) in Nazi uniforms proved a difficult sell. Still, Melville convinced the Parisian government to allow it. An aperture to the rest of the film, soldiers step directly toward the camera as if about to march right through the screen to trample the audience, filling the viewer with dread and with the promise of an equally despairing finale.

Film historians and Melville scholars have noted that Army of Shadows bears a “funeral tone” throughout, as if mourning the Resistance fighters either already dead or soon to die within the picture. Melville’s films often brood, and in many cases, preemptively grieve for the hero’s death. Then again, one could interpret his cinematic moods as simply pensive—a stylistic trait that creates atmosphere through silent protagonists. Except, such an explanation is perhaps too simple when looking at his career. In Le samouraï and Le Cercle rouge, for example, his narcissistic heroes harbor the same meditative disposition as Army of Shadows’ lead Philippe Gerbier (played by Lino Ventura)—in each of these three films, the tone reaches levels of almost ceremonial stoicism, and in each, the so-called hero dies in the end. Whereas in Bob le flambeur, the hero’s attitude is relatively blithe, allowing the protagonist to live. Melville constructs the tone, the lack of dialogue and humor, as part of his minimalist style. The result in Army of Shadows is an appropriately poetic feel given this comparatively serious subject matter, both poignant and harrowing next to Bob le flambeur.

Film historians and Melville scholars have noted that Army of Shadows bears a “funeral tone” throughout, as if mourning the Resistance fighters either already dead or soon to die within the picture. Melville’s films often brood, and in many cases, preemptively grieve for the hero’s death. Then again, one could interpret his cinematic moods as simply pensive—a stylistic trait that creates atmosphere through silent protagonists. Except, such an explanation is perhaps too simple when looking at his career. In Le samouraï and Le Cercle rouge, for example, his narcissistic heroes harbor the same meditative disposition as Army of Shadows’ lead Philippe Gerbier (played by Lino Ventura)—in each of these three films, the tone reaches levels of almost ceremonial stoicism, and in each, the so-called hero dies in the end. Whereas in Bob le flambeur, the hero’s attitude is relatively blithe, allowing the protagonist to live. Melville constructs the tone, the lack of dialogue and humor, as part of his minimalist style. The result in Army of Shadows is an appropriately poetic feel given this comparatively serious subject matter, both poignant and harrowing next to Bob le flambeur.

This is not to discount Melville’s gangster films from his typically more serious work, such as Army of Shadows, Silence, or Léon Morin, prêtre; on the contrary, these tonal similarities bring them closer together. Melville’s stories, regardless of genre, act as tenants to his distinctive style; the plot is secondary to the film’s mood—an atmospheric architecture where aesthetics take precedence. His characters even dress the same: Gangsters, Nazi Intelligence, and Resistance members all wear similar trench coats, with collars up and guns concealed in their pockets, as if out of a 1940s Hollywood gangster picture. Certainly, the assassination of Mathilde (Simone Signoret) in the finale of Army of Shadows better resembles a Capone-style drive-by more than a covert execution.

Occupying Melville’s crime-centric pictures are limited dialogue, a diminutive score, and an overall pensive tone. These traits describe his frequently used loner male protagonist, who is made into a glorification of cool criminality through Melville’s stylistic tendencies. For Army of Shadows, the same features add impressively involving layers of drama onto the wartime mise-en-scène. The limited dialogue and withdrawn personalities become pathos for the Resistance: an organization based more on a philosophy than its actions, hence its obstinacy amid hopelessness. Present in Melville’s gangsters and maquis is a sense of Freudian death drive, wherein the subject becomes fated by an insatiable desire to end itself. Alain Delon’s characters in both Le samouraï and Le Cercle rouge could have avoided their eventual demises, but they were drawn to a place or a final score, at last leading to their death.

Resistance maquis behave much in the same way as they fight, from the mouse’s point of view, an elephantine opposition. There were only around 600 members total in the French Resistance. They were mainly average Frenchmen—grocers, farmers, janitors, and salesman: the working class would rarely be suspected of espionage. Most of them died for their country. That is not to say that they did not fear death, but they did open themselves up to it. On any given mission, Resistance fighters are compensated for their efforts with death; it is the given reward for their dedicated service. With every mission accomplished, they pull themselves closer to their own end. At one point, Gerbier is told the police are looking for him, that he should lie low. He says he cannot, that someone must train the new members. He almost invites capture, and eventually, his own demise.

It comes as no surprise that, moments later, he is caught. And captured for the second time, Gerbier and his fellow prisoners are placed in front of machine guns by the Nazis, who tell the prisoners to start running. The machine guns will start in a moment. Whoever makes it to the far wall, roughly 100 yards down in an underground corridor, will survive until the next group of prisoners is lined up. After an officer gives the command to fire, the prisoners take off running for their lives, but Gerbier does not move, as if he wants to die. The officer shoots at Gerbier’s feet; he instinctively runs. All at once, smoke fills the corridor, and Gerbier sees a rope. Rescued by his people, he later explains that death would have been a release. Gerbier’s words describe how Melville’s representation of the Resistance shows people tired but persistent, mercilessly driven by duty, yet thankful when it all ends.

Because self-sacrifice is unconsciously, and sometimes consciously, pursued, the violence subsists without romanticism or escapism; instead, it suffers a somber fatalism. In the film’s most difficult scene, Gerbier and two others are required to kill a traitor. To keep the incident quiet so as not to alert neighbors, they must strangle him. A towel is wrapped around the young traitor’s throat. And yet, the camera concentrates on the Resistance men, not the victim. This is their first time killing one of their own, which is clear by their faces. We are never more concerned about revenge or justice in this scene; rather, Melville invests us in how exacting punishment drains Gerbier and the others. The director’s treatment of the Resistance distinguishes itself from the satisfying espionage action of, say, John Frankenheimer’s The Train and films like it by meditating on the protagonists’ fates.

If Melville wished, he could have added action into Army of Shadows, making scenes like the escape attempt from the Gestapo prison in Lyon more about brute force than suspense. When maquis member Lepercq is captured, tortured, and imprisoned, Gerbier allows a break-out attempt where three Resistance fighters go undercover as medical transports. But rather than grandiose music and energized camerawork, Melville shoots this scene like many of his finest sequences—with no music and patient concentration on detail. This scene compares to the robbery from Le Cercle rouge or the train heist from Un flic, as all are virtually silent, meticulously paced, and with little focus on dialogue. His approach is intellectual rather than physical, making us ponder the frame of mind on display. Recognizing the process of decision-making becomes more important than action or suspense. Having fought in the Resistance, Melville understands such a state of mind more than any other filmmaker, which is why Army of Shadows emerges as a meditation more than a historical account. The film’s events are not realistic, save for their psychology. It contemplates the type of person required to expect betrayal around each corner, to prepare for any unforeseen event, and to survive, all using Melville’s penchant for masculinized storytelling.

At least one woman is present in Melville’s film, but in a way that removes her femininity. Signoret plays Mathilde, just as valuable a member of her Resistance group as any one of the men. Mathilde is an older, de-sexualized woman. Dressed in common, muted colors, she integrates into the Resistance collective as easily as if she were male. Years prior, Signoret was a beauty in Casque d’or and Diabolique; in Army of Shadows, she is one of the boys, showing but a glimmer of femininity only once in the film—in her glassy eyes after failing to free their comrade from the Lyon prison. Melville has often been criticized for depicting women only as set-pieces to the director’s male hero. Here, though she lacks cinema’s stereotypical feminine qualities, namely sexuality, she is nonetheless a strong female hero. By the end of the film, Melville asserts that Mathilde may be the most valuable member of the film’s Resistance group.

After Mathilde is captured, her death is ordered, but the order is met with opposition. Gerbier’s group believes she made more sacrifices and arranged more operations than any other, which places her in their debt. Nonetheless, it is Melville’s notion that Resistance fighters must continue, even if they must kill each other; thus, they bring themselves closer to their demise. Finally, Mathilde is assassinated by Luc Jardie, the leader of Gerbier’s Resistance cell, as his car pulls away with Gerbier, Le Bison, and Le Masque riding there with him. All are witnesses to the tragic truth of the Resistance—that all will eventually meet the same fate of death. In the end, though we never see Gerbier and his comrades depart, the epilogue titles tell us how each Resistance member is finally caught and executed or killed.

Army of Shadows barely received acknowledgment in France upon its initial release; the critical response was polarized, and the film did not perform well at the French box office. Ginette Vincendeau attributes the film’s failure to poor timing. It was considered a Gaullist picture. Soon enough, General de Gaulle was voted out of politics after the student strike of May 1968, at which point Gaullist theory was unpopular. And so the film never obtained U.S. distribution. Melville, however, did receive several letters from real-life Resistance members praising him for his affecting and accurate film. While in France Army of Shadows was remembered fondly over time, even the most devout American cinephile could not place it within Melville’s oeuvre unless they had seen it in France during its initial theatrical run. In 2006, Rialto Pictures circulated a print around art house and minor revival theaters in America, introducing this forgotten classic to new audiences. The film received massive critical acclaim, with many calling it the best film released that year.

Army of Shadows barely received acknowledgment in France upon its initial release; the critical response was polarized, and the film did not perform well at the French box office. Ginette Vincendeau attributes the film’s failure to poor timing. It was considered a Gaullist picture. Soon enough, General de Gaulle was voted out of politics after the student strike of May 1968, at which point Gaullist theory was unpopular. And so the film never obtained U.S. distribution. Melville, however, did receive several letters from real-life Resistance members praising him for his affecting and accurate film. While in France Army of Shadows was remembered fondly over time, even the most devout American cinephile could not place it within Melville’s oeuvre unless they had seen it in France during its initial theatrical run. In 2006, Rialto Pictures circulated a print around art house and minor revival theaters in America, introducing this forgotten classic to new audiences. The film received massive critical acclaim, with many calling it the best film released that year.

Although Kessel’s book ends hopefully, it was written during the war, so understandably the novel focuses on hope rather than despair. Melville’s Army of Shadows is quite the reverse. The film was a historical marker for the director, signifying his generation—the pre-May 1968 generation. It does not highlight the past or future but remains in the film’s present: the severe and disciplined mental state necessary for maquis cells to operate during World War II. For every procession of German soldiers marching on the Champs-Elysées, a small company of everyday Frenchmen worked in the gloom of their eventual deaths to stop them.

Bibliography:

Vincendeau, Ginette. Jean-Pierre Melville: An American in Paris. London: British Film Institute, 2003.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review