The Definitives

Aliens (1986)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

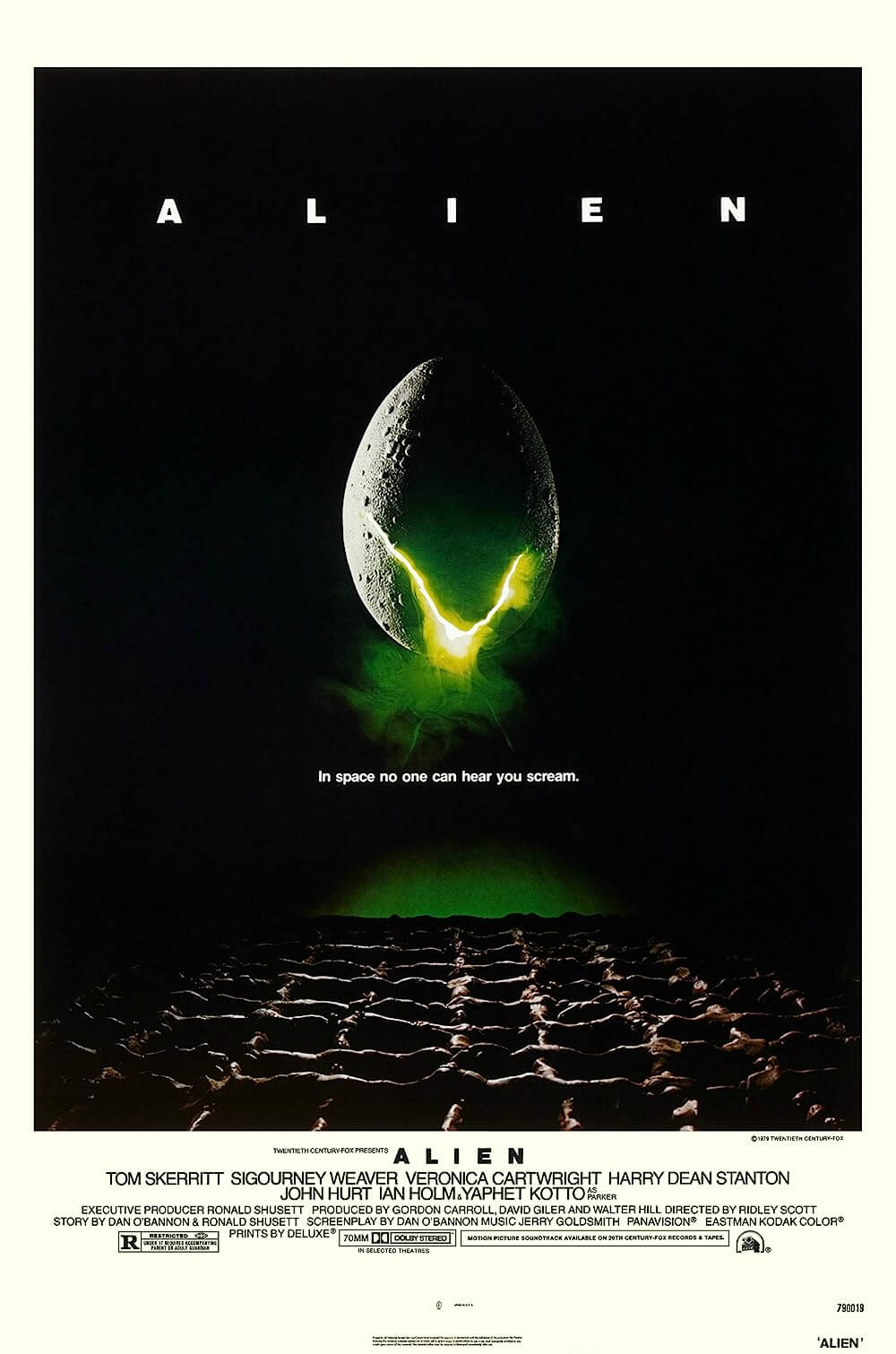

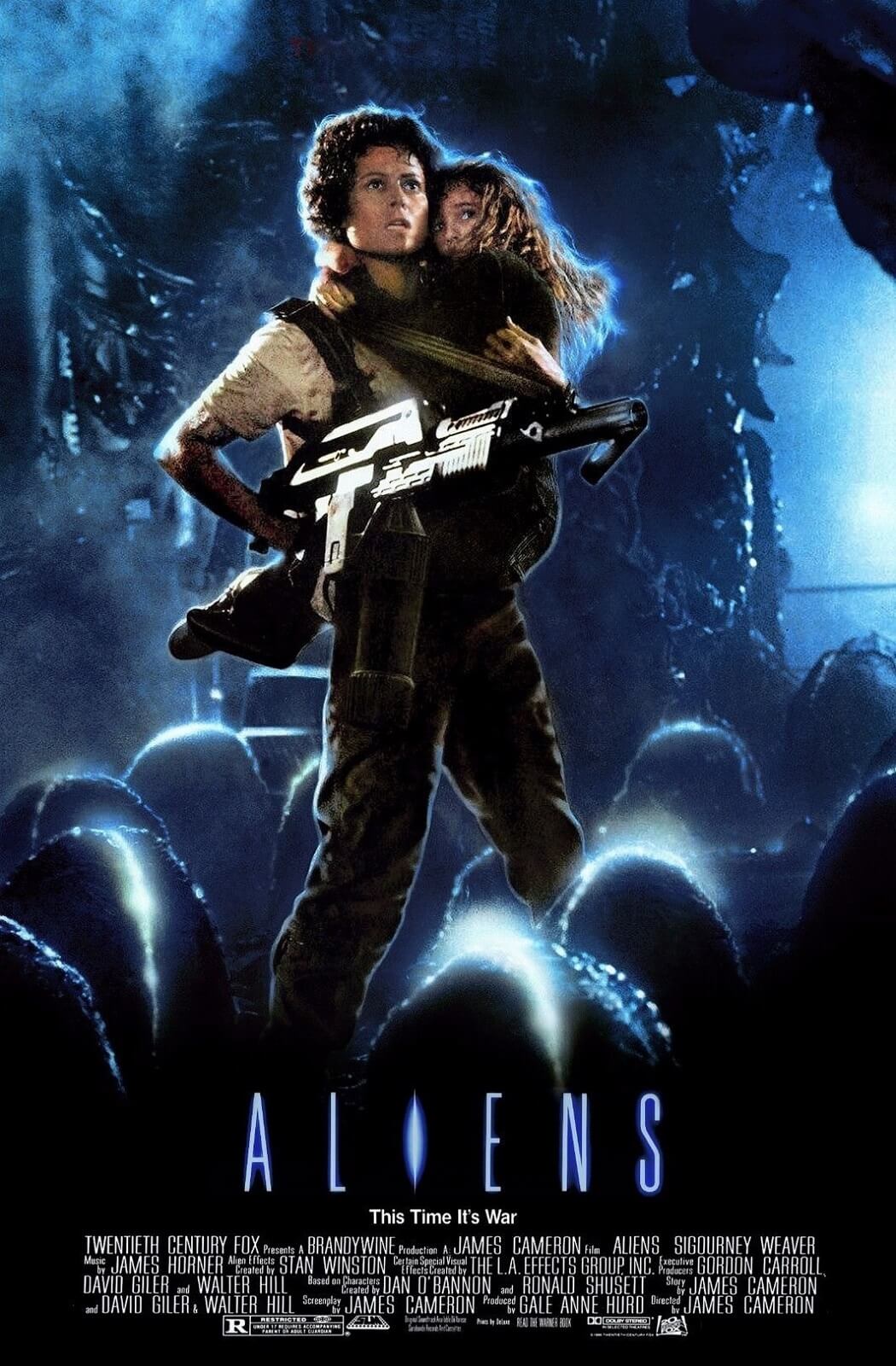

In 1986, James Cameron made the quintessential sequel: Aliens, a model for all sequels as to what they could and should aspire to be. Serving as writer and director for only the third time, Cameron reinforces themes and develops the mythology from Ridley Scott’s 1979 original, Alien, and expands upon those ideas by also distinguishing his film from its predecessor. The short of it is, Cameron goes bigger—much bigger—yet does this by remaining faithful to his source. Instead of simply replicating the single-alien-loose-on-a-haunted-house-spaceship scenario, he ups the ante by incorporating multitudes of aliens and also Marines to fight them alongside our hero, Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley. Still working within the guise of science-fiction’s hybridization with another genre, Cameron delivers an epic actionized war thriller rather than a horror film, and effectively changes the genre from the first film to second to suit the demands of his narrative and personal style. Through this setup, Cameron completely differentiates his film from Alien. And in his stroke of genius innovation, he made movie history by achieving something rare: the perfect sequel.

Opening precisely where the original left off, though 57 years later, the film finds Ripley, the last survivor of the Nostromo, drifting through space when she is discovered in prolonged cryogenic sleep by a deep space salvage crew. She wakes up on a station orbiting Earth traumatized by chestbursting nightmares, and her story of a hostile alien is met with disbelief. The moon planetoid LV-426, where her late crew discovered the alien, has since been terra-formed into a human colony by Weyland-Yutani Corporation (whose motto, “Building Better Worlds” is ironically stenciled about the settlement), except now communications have been lost. To investigate, the Powers That Be resolve to send a team of Colonial Marines, and they ask Ripley along as an advisor. What Ripley and the Marines find is not one alien but hundreds that have established a nest within and from the human colony. Cameron’s approach turns the single beast into an anonymous threat, but also considers the frightening nest mentality of the monsters and their willingness to carry out orders given by a maternal Queen, who defends her hive with a vengeance. Alongside the aliens are an unrelenting series of situational disasters threatening to trap Ripley and crew on the planetoid and blow them all to smithereens. The result is a nonstop swelling of tension, enough to cause reports of physical illness in initial audiences and critics, and enough to burn a place into our moviegoer memory for all time.

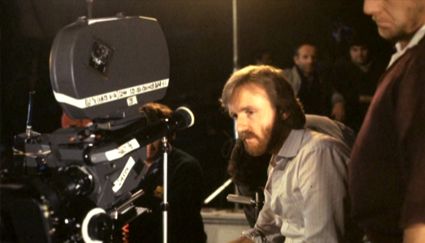

During his preparation for The Terminator in 1983, Cameron expressed interest to Alien producer David Giler about shooting a sequel to Scott’s film. For years, 20th Century Fox showed little interest in a follow-up to Scott’s film and changes in management prevented any proposed plans from moving forward. Finally, they allowed Cameron to explore his idea, and an imposed nine-month hiatus on The Terminator (when Arnold Schwarzenegger was unexpectedly obligated to shoot a sequel to Conan the Barbarian) gave Cameron time to write. Inspired by the works of sci-fi authors Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov, and producer Walter Hill’s Vietnam War film Southern Comfort (1981), Cameron turned in ninety pages of an incomplete screenplay barely into the second act; but what pages the studio could read made an impression, and they agreed to wait for Cameron to finish directing duties on The Terminator, the result of which would determine if he could finish writing and ultimately helm his proposed sequel, entitled Aliens. After The Terminator’s triumphal release, Cameron and his producing partner wife Gale Anne Hurd were given an $18 million budget to complete Aliens, an alarmingly small sum when measured against the epic-looking finished film.

During his preparation for The Terminator in 1983, Cameron expressed interest to Alien producer David Giler about shooting a sequel to Scott’s film. For years, 20th Century Fox showed little interest in a follow-up to Scott’s film and changes in management prevented any proposed plans from moving forward. Finally, they allowed Cameron to explore his idea, and an imposed nine-month hiatus on The Terminator (when Arnold Schwarzenegger was unexpectedly obligated to shoot a sequel to Conan the Barbarian) gave Cameron time to write. Inspired by the works of sci-fi authors Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov, and producer Walter Hill’s Vietnam War film Southern Comfort (1981), Cameron turned in ninety pages of an incomplete screenplay barely into the second act; but what pages the studio could read made an impression, and they agreed to wait for Cameron to finish directing duties on The Terminator, the result of which would determine if he could finish writing and ultimately helm his proposed sequel, entitled Aliens. After The Terminator’s triumphal release, Cameron and his producing partner wife Gale Anne Hurd were given an $18 million budget to complete Aliens, an alarmingly small sum when measured against the epic-looking finished film.

Cameron’s beginnings as an art director and designer under B-movie legend Roger Corman, however, gave the ambitious filmmaker experience in stretching a small budget. The production filmed at Pinewood Studios in England and gutted an asbestos-ridden, decommissioned coal power station to create the human colony and alien hive. His precision met some opposition with the British crew, some of whom had worked on Alien and all of whom revered Ridley Scott. None of them had seen The Terminator, and so they were not yet convinced this relative no-name hailing from Canada could step into Scott’s shoes; when Cameron tried to set up screenings of his breakthrough actioner for the crew to attend, no one showed. On the flipside, Cameron’s notorious perfectionism and hard-driving temper flared when production halted mid-day for tea, a contractual obligation on all British film productions. Many a tea cart met its demise by Cameron’s hand. Culture and personality clashes abound, the production lost a cinematographer and actors to Cameron’s entrenched resolve. Still, the director’s vision and skill eventually won over most of the crew—even if his personality did not—as he demonstrated a clear vision and employed clever technical tricks to extend their budget.

No end of in-camera effects, mirrors, rear projection, reverse motion photography, and miniatures were designed by Cameron, concept artist Syd Mead, and production designer Peter Lamont to extend their budget. H.R. Giger, the visual artist behind the original alien’s design, was not consulted; in his place, Cameron and special FX wizard Stan Winston conceived the alien Queen, a gigantic fourteen-foot puppet requiring sixteen people to operate its hydraulics, cables, and control rods. Equally elaborate was their Powerloader design, a futuristic heavy-lifting machine, operated behind the scenes by several crew members. The two massive beasts would collide in the film’s iconic finale duel, requiring some twenty hands to execute. Only in-camera effects and smart editing were used to produce this seamless sequence. Lightweight alien suits painted with a modicum of mere highlight details were worn by dancers and gymnasts, and then filmed under dark lighting conditions, rendering vastly mobile creatures that appear almost like silhouettes. The effect allowed Cameron’s alien drones to run about the screen, leaping and attacking with a force unlike what was seen in the brooding movements of the creature in Scott’s film. Cameron even worked closely with sound effect designer Don Sharpe, laboring over audio signatures for the distinctive alien hissing, pulse rifles, and unnerving bing of the motion-trackers. He toiled over such details down to just weeks before the premiere, and Cameron’s schedule meant composer James Horner had to rush his music for the film—but he also delivered one of cinema’s most memorable action scores. No matter how hard he pushes his crew, Cameron’s method, it must be said, produces results. Aliens would go on to earn several technical Academy Award nominations, including Best Sound, Best Film Editing, Best Art Direction/Set Decoration and Best Music, and two wins for Sound Effects Editing and Visual Effects.

No end of in-camera effects, mirrors, rear projection, reverse motion photography, and miniatures were designed by Cameron, concept artist Syd Mead, and production designer Peter Lamont to extend their budget. H.R. Giger, the visual artist behind the original alien’s design, was not consulted; in his place, Cameron and special FX wizard Stan Winston conceived the alien Queen, a gigantic fourteen-foot puppet requiring sixteen people to operate its hydraulics, cables, and control rods. Equally elaborate was their Powerloader design, a futuristic heavy-lifting machine, operated behind the scenes by several crew members. The two massive beasts would collide in the film’s iconic finale duel, requiring some twenty hands to execute. Only in-camera effects and smart editing were used to produce this seamless sequence. Lightweight alien suits painted with a modicum of mere highlight details were worn by dancers and gymnasts, and then filmed under dark lighting conditions, rendering vastly mobile creatures that appear almost like silhouettes. The effect allowed Cameron’s alien drones to run about the screen, leaping and attacking with a force unlike what was seen in the brooding movements of the creature in Scott’s film. Cameron even worked closely with sound effect designer Don Sharpe, laboring over audio signatures for the distinctive alien hissing, pulse rifles, and unnerving bing of the motion-trackers. He toiled over such details down to just weeks before the premiere, and Cameron’s schedule meant composer James Horner had to rush his music for the film—but he also delivered one of cinema’s most memorable action scores. No matter how hard he pushes his crew, Cameron’s method, it must be said, produces results. Aliens would go on to earn several technical Academy Award nominations, including Best Sound, Best Film Editing, Best Art Direction/Set Decoration and Best Music, and two wins for Sound Effects Editing and Visual Effects.

Though Cameron’s most obvious signatures reside in his obsession with tech, rarely is he given credit for his dramatic additions to the franchise. Only because her Weyland-Utani contact, Carter Burke (a slithery Paul Reiser), promises their mission is to wipe out the potential alien threat and not return with one for study, does Ripley agree to going back out into space. Cameron deepens Ripley by transforming her into a somewhat rattled protagonist at first, disconnected from a world that is not her own. In her time away, her family and friends have all died; we learn Ripley had a daughter who passed while she was in hyper-sleep. She is alone in the universe. It is her desire to reclaim her life and her concern about the colony’s families that impels her back into space. But when they arrive at LV-426 and discover evidence of a massive alien attack, her motherly instincts take over later as they locate a sole survivor, a 12-year-old girl nicknamed Newt (Carrie Henn). A mini-Ripley of sorts, Newt too has survived the alien by her ingenuity and wits, and almost instantly she becomes Ripley’s daughter by proxy. Moreover, like Ripley, Newt attempts to warn the Marines about the dangers that await them, and likewise her warnings go ignored.

For his ensemble of Colonial Marines, Cameron cast several members of his veritable stock company, all capable of the larger-than-life personalities assigned to them. The inexperienced Lieutenant Gorman (William Hope) puts on airs and old hand Sergeant Apone (Al Matthews) barks orders like a drill instructor. Privates Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein, who later appeared in Terminator 2: Judgment Day) and Hudson (Bill Paxton, who worked with Cameron on several Corman flicks and appeared in The Terminator as a punk thug) could not be more different, she a resolute “tough hombre” and he an all-talk badass who turns into a sniveling defeatist when the pressure is on (“Game over, man!”). Ripley is weary of the android Bishop (Lance Henriksen, who starred in Cameron’s first two directorial efforts), but the innocent, childlike gloss in his eyes never betrays its promise. For Corporal Hicks, Ripley’s pseudo-love interest and the Marine who takes charge when the rest are gone, Cameron originally cast James Remar, but personality conflicts led Cameron to recast. Michael Biehn took over, having just starred as the hero of The Terminator, and filled the character with a quiet heroism and dependability. As the story’s strain intensifies, Cameron never forgets to enlarge his characters through their reactions; by the end, not one of them feels one-dimensional or forgotten during the director’s writing process, the effect not unlike great Vietnam War movies of the preceding years (Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, etc.).

For his ensemble of Colonial Marines, Cameron cast several members of his veritable stock company, all capable of the larger-than-life personalities assigned to them. The inexperienced Lieutenant Gorman (William Hope) puts on airs and old hand Sergeant Apone (Al Matthews) barks orders like a drill instructor. Privates Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein, who later appeared in Terminator 2: Judgment Day) and Hudson (Bill Paxton, who worked with Cameron on several Corman flicks and appeared in The Terminator as a punk thug) could not be more different, she a resolute “tough hombre” and he an all-talk badass who turns into a sniveling defeatist when the pressure is on (“Game over, man!”). Ripley is weary of the android Bishop (Lance Henriksen, who starred in Cameron’s first two directorial efforts), but the innocent, childlike gloss in his eyes never betrays its promise. For Corporal Hicks, Ripley’s pseudo-love interest and the Marine who takes charge when the rest are gone, Cameron originally cast James Remar, but personality conflicts led Cameron to recast. Michael Biehn took over, having just starred as the hero of The Terminator, and filled the character with a quiet heroism and dependability. As the story’s strain intensifies, Cameron never forgets to enlarge his characters through their reactions; by the end, not one of them feels one-dimensional or forgotten during the director’s writing process, the effect not unlike great Vietnam War movies of the preceding years (Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, etc.).

To be sure, the director’s fascination with special FX, futuristic hardware, gun fetishization, and militarism informed many plot elements and designs, all closely linked in some way to Vietnam War imagery. The Marine’s space ship, the Sulaco, was conceived with clear forward momentum (unlike the square, towering Nostromo) resembling the shape of a gun. Their dropships are mashup designs of F-4 Phantom jets and AH-1 Cobra helicopters of the Vietnam War. The Marines themselves were garbed in rugged armor decorated with personalized graffiti, maxims reminiscent of “Born to Kill” and so forth, and equipped with massive firepower. These over-armed Marines hunt an unseen force in a hostile environment; they enter cocky and certain of their own superiority, only to be cut down by “animals”. Their invested superiors have explicit corporate interests to protect, represented by Burke, making for apparent historical parallels but also a fixed theme in Cameron’s subsequent films. In that sense, Cameron may specifically channel Vietnam imagery here, but he also remarks on a time-honored human tradition in our willingness to sacrifice a group of people if it serves the perceived “greater good”. In the case of Aliens, Burke’s motivations are purely his own financial gain. His inhuman greed leads Ripley to one of the film’s best lines: “You know, Burke, I don’t know which species is worse. You don’t see them fucking each other over for a goddamn percentage.”

To emphasize his Vietnam parallel, Cameron outlines a hopeless situation that goes from bad to worse in a series of impossibly horrific events. Having located the colonists through transmitters that confirm they have been huddled together in one section of the complex, the Marines resolve to roll-in guns blazing and save the day. What they find, however, are walls enveloped with cocoon-like resin and inside colonists who serve as hosts to alien Facehuggers. All at once, the aliens attack and, caught off guard, the Marine’s numbers are cut down to a handful. By the time they escape, their shootout has caused a reactor leak that will detonate in a number of hours. Panicked, outnumbered, outgunned, and now out of time, the few survivors huddle together, section themselves off, and attempt to devise a plan. To escape, they must manually fly down a dropship from the Sulaco. But as the coolant tower fails on the complex’s reactor, the entire site slowly goes to hell and will soon detonate in a thermonuclear explosion. And the persistent aliens never stop trying to penetrate the Marines’ defenses. If alien creatures and a massive blast were not enough, there’s also Burke’s attempt to impregnate Ripley and Newt as alien hosts, resulting in a sickening corporate betrayal. Each of these elements builds with unnerving pressure that leaves the audience totally absorbed and twisting internally.

To emphasize his Vietnam parallel, Cameron outlines a hopeless situation that goes from bad to worse in a series of impossibly horrific events. Having located the colonists through transmitters that confirm they have been huddled together in one section of the complex, the Marines resolve to roll-in guns blazing and save the day. What they find, however, are walls enveloped with cocoon-like resin and inside colonists who serve as hosts to alien Facehuggers. All at once, the aliens attack and, caught off guard, the Marine’s numbers are cut down to a handful. By the time they escape, their shootout has caused a reactor leak that will detonate in a number of hours. Panicked, outnumbered, outgunned, and now out of time, the few survivors huddle together, section themselves off, and attempt to devise a plan. To escape, they must manually fly down a dropship from the Sulaco. But as the coolant tower fails on the complex’s reactor, the entire site slowly goes to hell and will soon detonate in a thermonuclear explosion. And the persistent aliens never stop trying to penetrate the Marines’ defenses. If alien creatures and a massive blast were not enough, there’s also Burke’s attempt to impregnate Ripley and Newt as alien hosts, resulting in a sickening corporate betrayal. Each of these elements builds with unnerving pressure that leaves the audience totally absorbed and twisting internally.

Until the final thirty minutes of Aliens, the creatures, now dubbed “xenomorphs” (a name derived from the director’s boyhood short, Xenogenesis), seem almost circumstantial. In a final assault, their swarms have reduced the human crew down to Ripley, Hicks, and Bishop, and they have captured Newt for cocooning. Ripley must search for her alone, and after she rips the child from a prison of spindly webbing, she rushes headlong into the egg-strewn lair of the Queen, an immense creature excreting eggs from its oozing ovipositor. In Cameron’s hands, the xenomorph becomes more than a “pure” killing machine, but now a problem-solving species with clear motivations within a larger hive and analogous family values. Cameron underlines the family theme in both human and alien terms during an exchange of threats between the two jealous mothers to protect their offspring, Ripley with her proxy Newt wrapped around her torso and the Queen guarding her eggs. This tense moment of horrific calm bursts into Ripley raging as she opens fire on the Queen’s unfolding pods, then flees chase with the gigantic monster close behind to a breathless rescue by the Bishop-piloted dropship. The idea of motherly protection and retaliation comes to a glorious head aboard the Sulaco, when the Queen emerges from the dropship’s landing gear compartment only to face a Powerloader-suited Ripley, who snarls her iconic battle call, “Get away from her, you bitch!”

If the setting is Vietnam in space, how appropriate then that Weaver nicknamed her character “Rambolina”, equating Ripley to Sylvester Stallone’s shell-shocked Vietnam vet John Rambo from First Blood and its sequels (interesting note: at one point in the early ‘80s, Cameron had written a draft of Rambo: First Blood Part II). Certainly Ripley’s mental scarring from the events in Alien accounts for her sudden eruption of hostility on the alien Queen and its eggs, not to mention her general autonomous and take-charge attitudes throughout the film, but Cameron’s persistent need to keep families together in his works is Ripley’s true driving force. Weaver understood this, and therefore set aside her otherwise stringent anti-gun sentiments to embrace these other new dimensions for her character (a good thing too; in addition to the aforementioned Oscar nominations, Weaver received her first Academy Award nomination for Best Actress for playing Ripley the second time). Along with Hicks as the stand-in father (but by no means paterfamilias), she and Newt form a makeshift family Ripley is desperate to defend. It is that balance of gung-ho fearlessness and motherly instinct that makes Ripley such a powerful feminist figure and rare movie action hero. Alien may have made her a star, but Aliens transformed Sigourney Weaver and her Ellen Ripley into cultural icons whose status and importance in the annals of film history have been cemented.

If the setting is Vietnam in space, how appropriate then that Weaver nicknamed her character “Rambolina”, equating Ripley to Sylvester Stallone’s shell-shocked Vietnam vet John Rambo from First Blood and its sequels (interesting note: at one point in the early ‘80s, Cameron had written a draft of Rambo: First Blood Part II). Certainly Ripley’s mental scarring from the events in Alien accounts for her sudden eruption of hostility on the alien Queen and its eggs, not to mention her general autonomous and take-charge attitudes throughout the film, but Cameron’s persistent need to keep families together in his works is Ripley’s true driving force. Weaver understood this, and therefore set aside her otherwise stringent anti-gun sentiments to embrace these other new dimensions for her character (a good thing too; in addition to the aforementioned Oscar nominations, Weaver received her first Academy Award nomination for Best Actress for playing Ripley the second time). Along with Hicks as the stand-in father (but by no means paterfamilias), she and Newt form a makeshift family Ripley is desperate to defend. It is that balance of gung-ho fearlessness and motherly instinct that makes Ripley such a powerful feminist figure and rare movie action hero. Alien may have made her a star, but Aliens transformed Sigourney Weaver and her Ellen Ripley into cultural icons whose status and importance in the annals of film history have been cemented.

A continuing need to preserve the nuclear family prevails in Cameron’s work: Sarah Connor protects her unborn son and humanity’s savior John Connor alongside his future father Kyle Reese in The Terminator, and later protects the teenage John beside another fatherly substitute, Schwarzenegger’s good-hearted killer robot in Terminator 2: Judgment Day. Ed Harris’ undersea oil driller rekindles a failed marriage in the face of marine aliens and nuclear war in The Abyss (1989). Schwarzenegger’s superspy in True Lies (1994) shields his family by keeping them uninformed; but to stop a terrorist plot and save his kidnapped daughter, he must reveal his secret identity. Avatar (2009) follows a broken-down war vet who finds a new family and race amid a group of tribal aliens. But the preservation of family is not the only recurring Cameron theme originating in Aliens. Notions of corrupt corporations, advanced technologies manned by blue-collar workers, and the allure but ultimate failure of advanced tech when posited against Nature all have a place in Cameron’s films, and each has a foundational block in Aliens.

When it was released on July 18 of 1986, audiences and critics deemed the film a triumph, and many declared Cameron’s sequel had outdone Ridley Scott’s original. Only a week after its debut, Aliens made the cover of Time Magazine, and along with its impressive box-office and several Oscar nominations, Cameron’s film had achieved a kind of instant classic status. Unquestionably, Aliens is a more accessible picture than Alien, as beyond the science-fiction surroundings of each film, action and war pictures have larger audiences than horror. But if Cameron’s efforts can be faulted, it must be for his lack of subtlety and tempered artistry that by contrast allow Scott’s film to transcend its limitations and become a vastly finer work of cinema. There’s no one who does intricate and visionary blockbusters like Ridley Scott, but there’s no one who makes bigger, more macho, more wowing blockbusters than James Cameron. Indeed, a few years later, the director’s already ambitious runtime was extended from 137 to 154 minutes in a superior “Special Edition” for home video. The alternate version includes scenes deleted from the theatrical release, including references to Ripley’s daughter, the appearance of Newt’s family, and a scene foreshadowing the arrival of the alien Queen. But to ask which film is better ignores how the first two entries in the Alien series remain galaxies apart in story, technique, and impact.

When it was released on July 18 of 1986, audiences and critics deemed the film a triumph, and many declared Cameron’s sequel had outdone Ridley Scott’s original. Only a week after its debut, Aliens made the cover of Time Magazine, and along with its impressive box-office and several Oscar nominations, Cameron’s film had achieved a kind of instant classic status. Unquestionably, Aliens is a more accessible picture than Alien, as beyond the science-fiction surroundings of each film, action and war pictures have larger audiences than horror. But if Cameron’s efforts can be faulted, it must be for his lack of subtlety and tempered artistry that by contrast allow Scott’s film to transcend its limitations and become a vastly finer work of cinema. There’s no one who does intricate and visionary blockbusters like Ridley Scott, but there’s no one who makes bigger, more macho, more wowing blockbusters than James Cameron. Indeed, a few years later, the director’s already ambitious runtime was extended from 137 to 154 minutes in a superior “Special Edition” for home video. The alternate version includes scenes deleted from the theatrical release, including references to Ripley’s daughter, the appearance of Newt’s family, and a scene foreshadowing the arrival of the alien Queen. But to ask which film is better ignores how the first two entries in the Alien series remain galaxies apart in story, technique, and impact.

That comparing the first film to the second becomes a matter of apples and oranges is wonderfully uncommon. If more filmmakers took Cameron’s approach to sequel-making, Hollywood’s franchises might not seem so dull and homogenized today. With Aliens, Cameron refuses to reproduce Alien by carbon-copying its structure and simply relocating the same outline to another setting, and yet he reinforces the original’s themes in his own ways. Whereas Scott’s film explores the horrors of the Unknown, Cameron acknowledges human nature’s curiosity to explore the Unknown, and in doing so reveals a new series of terrifying and breathlessly thrilling discoveries. Infused with horror shocks, incredible action, unwavering machismo, state-of-the-art technological innovations, and on a more basic level great storytelling, Cameron’s film would become the first of his many “event movies”. After Aliens, he may have gone bigger or flashier, but his equilibrium between form and content has never been so balanced. It is a sequel to end all sequels.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review