The Definitives

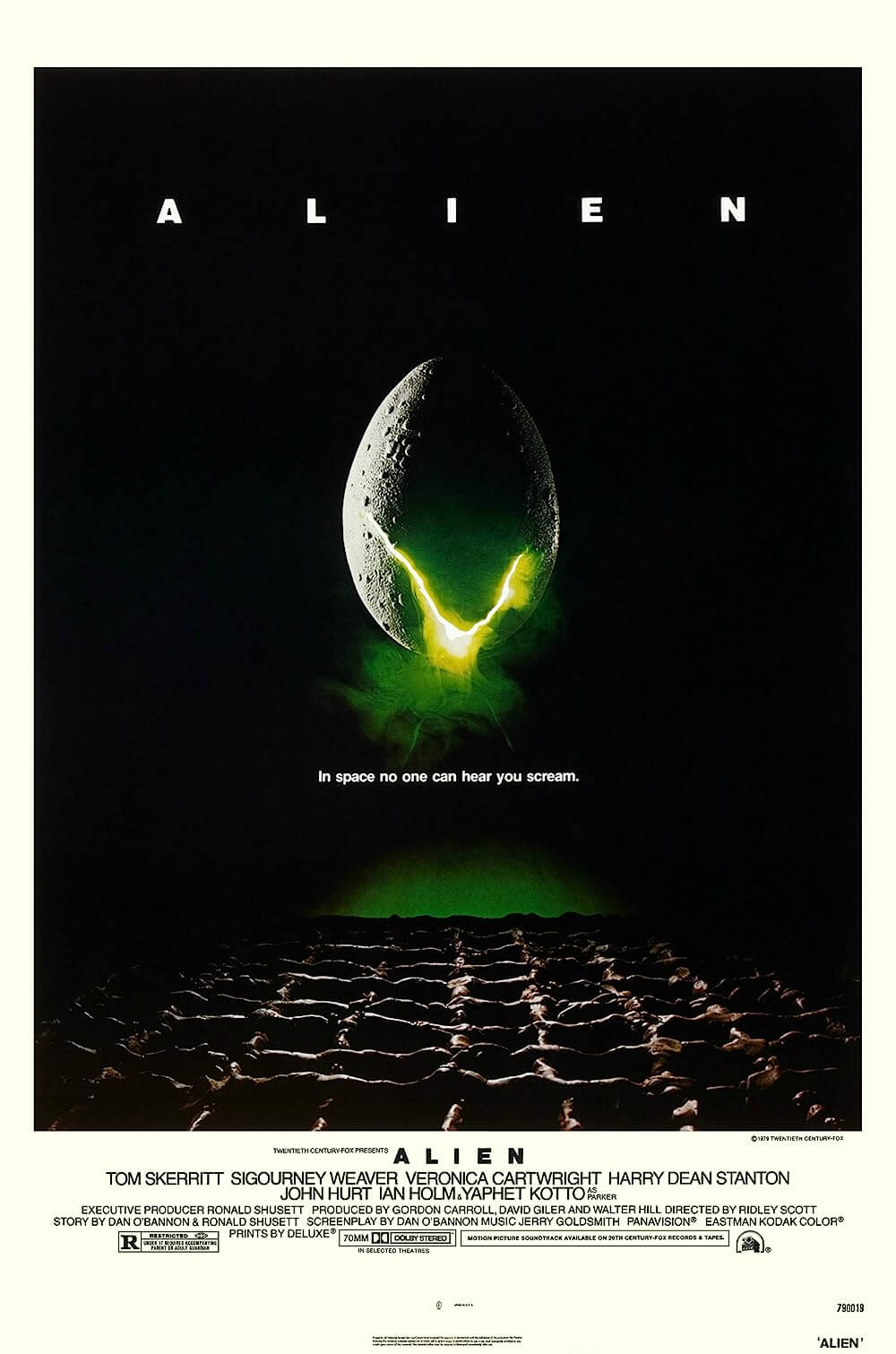

Alien (1979)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

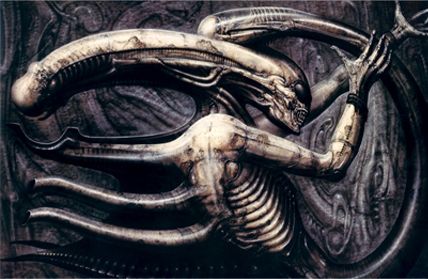

Visionary and terrifying, Ridley Scott’s Alien hybridized the horror and science-fiction genres in 1979 to effectively launch a new subgenre, and countless clones have since borrowed from its DNA. Space-aged operatics and laser battles have no place in this imaginatively designed film, whose mounting tension still contains fearsome intensity and whose visual ambitions still evoke awe. Scott’s artistry elevates the material with his majestic frames of industrial machinery drifting through space, debris-swept planetoids, and a ruined alien ship, contrasted by a close-quarters spacecraft setting and empty corridors packed with claustrophobic fright. The film’s suspense builds with measured steps until it reaches wrenching, unbearable proportions, wrought by H.R. Giger’s alien design and its arousal of penetrative psychosexual dread. Scott’s deliberate pacing prolongs our fear of the Unknown by staving off the alien’s arrival as long as possible, while our curiosity and growing fear gradually drives us mad; and when the monster is revealed with mere hints that defy precise description, its shadowy manifestations reserve the alien an eternal place in our nightmares.

Of course, Alien was not the first film about a killer creature from space, nor was it the first haunted house-type story in which characters are hunted down and systematically slaughtered, nor would it be the last. Screenwriter Dan O’Bannon later admitted, “I didn’t steal Alien from anybody. I stole it from everybody!” From the radio beacon of unknown origin in Forbidden Planet (1956) to the escalating alien scares in It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958) to the claustrophobic setting of The Thing from Another World (1951), the film is not without its influences. But Scott, along with writers O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett, innovate so much on established formulas that their treatment becomes something wholly original and influential. O’Bannon conceived the basic plotline after his experience making Dark Star in 1974—a similarly themed sci-fi comedy about an alien loose on a spaceship—with first-time director John Carpenter (The Thing). That film’s exceedingly low-budget and beach-ball alien inspired O’Bannon to try something else and incorporate horror ingredients into a more frightening alien recipe. Meanwhile, Shusett had secured rights to Philip K. Dick’s short story We Can Remember It For You Wholesale (which became Total Recall in 1990) and wanted O’Bannon to assist in its adaptation. When approached, O’Bannon pitched his originally titled “Star Beast” idea to Shusett; together they agreed to explore O’Bannon’s concept, it being the less costly and thus more feasible of their two potential projects.

Their development halted, however, when O’Bannon went to Paris for a proposed adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune under filmmaker Alexandro Jodorowsky. When that project fell through, O’Bannon’s interest in “Star Beast” was renewed because Jodorowsky had hired Swiss artist H.R. Giger to develop conceptual designs. Giger’s disturbing artwork in his book Necronomicon (1977) and its biomechanical, other-worldly quality fit O’Bannon and Shusett’s intentions for the newly titled Alien. Signing a deal with Walter Hill, David Giler, and Gordon Carroll’s production company Brandywine, the project was sold to 20th Century Fox as “Jaws in space”. Approved with a $4.2 million budget, the producers retooled O’Bannon and Shusett’s script, adding and fleshing out several ideas, while talks with various directors like Robert Aldrich and Peter Yates fell through. At the time, Ridley Scott was little more than a popular commercial director in England but his debut feature, The Duellists (1977), an elegant Napoleonic drama about an ongoing feud between two French soldiers, inspired confidence. A spectacular visualist, the strength of Scott’s storyboards incited Fox to double their original budget.

Born from a seed implanted by 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and Star Wars (1977), Scott’s precise hand on Alien has the most in common with Kubrick’s film, in that the film’s monster-from-space scenario contains a similar primordial and brooding quality, yet a strangely pragmatic tone and characters. Consider the opening scenes where the commercial mining tow ship Nostromo passes by in empty interstellar space, its geometric shapes and spires familiar images to 1970s audiences. Jerry Goldsmith’s almost white noise, vacuum-of-space score establishes the setting beyond unnerving the audience; he completely immerses us. Then Scott’s handheld camera navigates the ship’s vacant hallways, ostensible tunnels lined with the functional paneling of an extended maintenance room, narrow and constricted and envisioned by Scott and concept designer Ron Cobb with the uninviting corridors of a submarine in mind. This is the workplace of blue-collar miners to be sure, not some ultra-clean model of a utopian future. Scott’s extended shots also establish the immensity of space against the dark, enclosed setting of the horrors to come, as suggested by the film’s iconic tagline: “In space no one can hear you scream.” Unprecedented upon its release, the depiction of space travel is not romanticized for science-fiction fantasists, but rather downgraded into something isolating and practical and believable.

Floating in the silence of space, inside the Nostromo lights flicker on and computers scroll incoming transmissions. The crew of seven is awakened from their hyper-sleep. A breakfast table gathering ensues, and their overlapping dialogue is the first human sound in six minutes of screentime. They’re groggy but happy to be going home, far removed from the dangers of the spatial void surrounding them. After their meal, they assess their position and find the ship’s computer, named Mother, has taken them off-course and roused them early to investigate a transmission that could be a distress signal, or possibly a warning, although its origin is unknown. Protests notwithstanding, they investigate and discover a derelict alien craft on a small planetoid moon. Once inside, the human survey crew follows the craft’s structural passageways of gigantic black bone-like rods woven together. They find a massive Space Jockey pilot, an alien vestige whose chest has exploded from the inside. Did the pilot’s ship crash or land for repairs ages ago? What was the craft’s mission? These questions go unanswered, as one of the human crew finds a lair strewn with semi-transparent eggs. When an egg opens, an arachnidan parasite leaps from inside and attaches itself to his face. Back at the Nostromo, the crew attempts to remove the parasite but they find it bleeds acid capable of corroding their hull. Soon the parasite falls off on its own, but it has implanted something inside its victim. During a meal, another creature bursts from inside the man’s chest and scurries across the table. The crew stands frozen in absolute shock and terror. They attempt to locate it, but discover the alien has grown into a monstrous predator and intends to kill them off one-by-one.

Floating in the silence of space, inside the Nostromo lights flicker on and computers scroll incoming transmissions. The crew of seven is awakened from their hyper-sleep. A breakfast table gathering ensues, and their overlapping dialogue is the first human sound in six minutes of screentime. They’re groggy but happy to be going home, far removed from the dangers of the spatial void surrounding them. After their meal, they assess their position and find the ship’s computer, named Mother, has taken them off-course and roused them early to investigate a transmission that could be a distress signal, or possibly a warning, although its origin is unknown. Protests notwithstanding, they investigate and discover a derelict alien craft on a small planetoid moon. Once inside, the human survey crew follows the craft’s structural passageways of gigantic black bone-like rods woven together. They find a massive Space Jockey pilot, an alien vestige whose chest has exploded from the inside. Did the pilot’s ship crash or land for repairs ages ago? What was the craft’s mission? These questions go unanswered, as one of the human crew finds a lair strewn with semi-transparent eggs. When an egg opens, an arachnidan parasite leaps from inside and attaches itself to his face. Back at the Nostromo, the crew attempts to remove the parasite but they find it bleeds acid capable of corroding their hull. Soon the parasite falls off on its own, but it has implanted something inside its victim. During a meal, another creature bursts from inside the man’s chest and scurries across the table. The crew stands frozen in absolute shock and terror. They attempt to locate it, but discover the alien has grown into a monstrous predator and intends to kill them off one-by-one.

Scott’s technique lends Alien distinction amid its respective genres at the time; rather than have the alien leap at the viewer from the start, he builds suspense through a meticulously controlled intensification of anxiety. Take the sound design and the careful juxtaposition of agonizing, dominating silence and jarring bursts of audible terror. The Nostromo’s crew moves about the quiet ship in virtual silence, their dialogue limited at first. Ambient noise and Goldsmith’s score feel all but nonexistent before the alien arrives on board, and the lack of even inconsequential sounds seems to emphasize the ship’s initial state of peace. After more than half the crew is dead, Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) has activated the ship’s auto-destruct sequence, and the noise suddenly becomes unbearable. Air duct fans throughout the Nostromo create ingenious visual and aural effects. Warning lights twirl. Flashes in the dark produce a staccato strobe, and the pulsating light reflects the sound of our own heartbeats thumping in fear. Scott’s camera captures every bead of sweat, piece of grit, and droplet of alien slime in the frame. Though Derek Vanlint received credit as cinematographer, Scott himself operated the handheld camera during the film’s mobile scenes, shooting Weaver in close-up, the strobes bouncing off her face as she turns to the next corridor with her back against the wall, knowing the alien might be waiting for her around the corner.

Scott’s moody treatment of the plot is counterbalanced by his talented ensemble, who gives the film an unmistakable human dimension in the coldness of space. Wage slaves all, the Nostromo’s crewmembers behave like interstellar working stiffs, led by their mellow captain, Dallas (Tom Skerritt). Second in command is the good-humored Kane (John Hurt), host to the alien organism. Next in line is warrant officer Ripley, who tries to quarantine Kane, but her adherence to protocol is defied by the icy science officer, Ash (Ian Holm), who allows Kane onboard. On the sidelines and informing the audience’s reactions are edgy navigator Lambert (Veronica Cartwright), and maintenance men Parker (Yaphet Kotto) and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton), who quibble tirelessly about getting paid less than their fellow crew members. Most impressive is that the youngest actor among them is Cartwright at 29. If Alien were made today by another filmmaker, it may have been populated by the time’s youngest and hottest stars. Scott’s intention, however, was to find a cast that could bring natural performances to an unnatural setting, and these actors lend the picture that needed texture of humanity and everyday behavior. For the film’s startling and bloody chestbuster scene, the director and Hurt prepared without telling the other actors just how it would play out; this now iconic movie moment features improvised yet natural reactions from actors shocked by the amount of fake blood spurting from Hurt’s body, but also from his jarring physical performance.

Because the performances seem so natural, the film disarms the audience and waylays us when Ash is revealed to be an android, embedded into the crew’s ranks to execute orders given by the Weyland-Utani Corporation, the crew’s employers and this series’ enduring evil empire. After Dallas has disappeared during his attempt to locate the alien, and with Kane dead, Ripley is left in charge and wants answers from Mother. Mother’s responses are cryptic and cite “Special Order 973” as a company directive that places highest priority on returning the alien organism intact—crew expendable—to study and somehow turn it into a bio-weapon. At once, the terror swells as Ash corners Ripley to seize control and silence her by forcing a rolled-up magazine down her throat. Parker and Lambert stop him, and during their attack they expose Ash’s milky synthetic insides; they are as shocked as we are to learn what Ash is, and how their situation has gone from bad to worse. All but decapitated, Ash’s head is mounted on a table and rewired so the remaining crew can get answers. With cold, smug superiority, he drones on about the alien’s qualities, “I admire its purity. A survivor. Unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality… I can’t lie to you about your chances, but… you have my sympathies.” Not only has the alien fright terrified the audience, but now we are stricken with corporate paranoia, which in turn layers the scenario from a simple alien body count movie into one that heightens our feelings of tension and isolation in the loneliness of space.

Beyond the excruciating tension, what remains so haunting about the film is how little it tells us about the alien, its origins, life cycle, and even its physical makeup. Its metamorphosis from parasite Facehugger to embryo Chestbuster to predatory Alien attacks its victims on multiple levels. In one way, it acts like a disease, invading the body and destroying from within. In another very suggestive way, it penetrates the body both in its parasitic and predatory forms. As Ash observes, “A perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility.” But the monster’s biology has its parallels in Earth nature, though they were undoubtedly unconscious associations made by Giger’s surreal paintings. The way the Facehugger implants its embryo recalls ichneumon wasps who lay their eggs on or inside their prey, while the alien’s tongue-like Pharyngeal jaws emerge from its mouth and call to mind a Moray eel. In its full-grown state, the humanoid creature appears to stand about seven feet tall, but Scott’s careful angles avoid giving audiences a full look; other times, he shoots the alien so it appears completely onscreen, but in such a way that the audience has no idea what they’re seeing. It appears skeletal, with an exposed rib cage, barbed tail, and vertebrae protrusions that appear to be biomechanical armor, and so it blends perfectly with the Nostromo‘s vast pipes and paneling. Giger’s original illustrations featured eyes and a skull-like visage inside its elongated head; when Giger himself was onset painting props based on his designs, the eyes were covered with a dome to suggest a lack of humanness.

But these are just physical qualities. Violent psychosexual connotations go further to instill terror and unease, as the victim’s participation in the alien life cycle amounts to non-consensual reproduction or rape. As a conscious reaction to the horror genre’s trend of using women as rape victims or damsels in distress, O’Bannon and Shusett wanted a creature that would create untold fear in male audiences and empower their leading protagonist, a woman. Even in his alien paintings, Giger’s often sexually explicit art contains redolent sexual symbols, and there was an intended effort on the part of the filmmakers to implant such discomfort in male viewers. Leaping from a vaginal egg whose opening was conceived by Giger to appear like an X-shaped vulva, the Facehugger’s process of impregnation commits an oral invasion into Kane, who is then subject to sexual reassignment as he becomes the mother of the penile Chestburster. Ash later whispers, “Kane’s son.” The phallic associations are many, not the least of which is the grown alien’s tube-like head, designed by Giger to resemble a penis. The creature’s lips, dripping with sexual lubricant used by the filmmakers to simulate alien saliva, spread to reveal vagina dentata teeth and jaws that open to unleash a phallic double-jaw. When the alien’s jaw slowly emerges in the finale, the extension is cut against a scantily clad Ripley, and the edited association brings to mind a forming and dripping erection, fuelling eroticism into a tense horror scene. Opposing male and female sexual allusions stimulate our sense of confusion about a monster whose onscreen presence was intended to implant a fearsome sexual identity crisis from our momentary glimpses.

While Giger’s sexualized alien design introduced what would become an iconic horror image, the film also introduces audiences to one of cinema’s strongest female heroes in Weaver’s Ripley. Though originally written as a man, Ripley and several other characters were conceived so their gender could be switched if needed, and producers Giler and Hill wanted the hero to be a woman. Aside from experience on Broadway, Weaver was a relative unknown and was the last actor cast; her audition was strong enough to change the producers’ original decision to cast Cartwright as Ripley. This last-minute choice became a fateful one for Weaver, whose career has been long-associated with the Alien franchise, having appeared in four entries through 1997. More significantly, though, Weaver’s initial presence as an iron-willed heroine afforded audiences a tough and noble hero, whose femininity was downplayed but not altogether absent. For decades, Weaver would be the only actress in Hollywood who could headline an action film, while her dramatic and genre work remained steady: she played an ironic damsel in the Ghostbusters series, earned two Oscar nominations in 1988 playing Dian Fossey in Gorillas in the Mist and a relentless business executive in Working Girl, explored arthouse drama with Roman Polanski’s Death and the Maiden (1997) and Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm (1997), and remains forever linked to the science-fiction and horror genres since this breakthrough performance. One of the great pleasures of watching Alien is witnessing Weaver grow into a star right before our eyes.

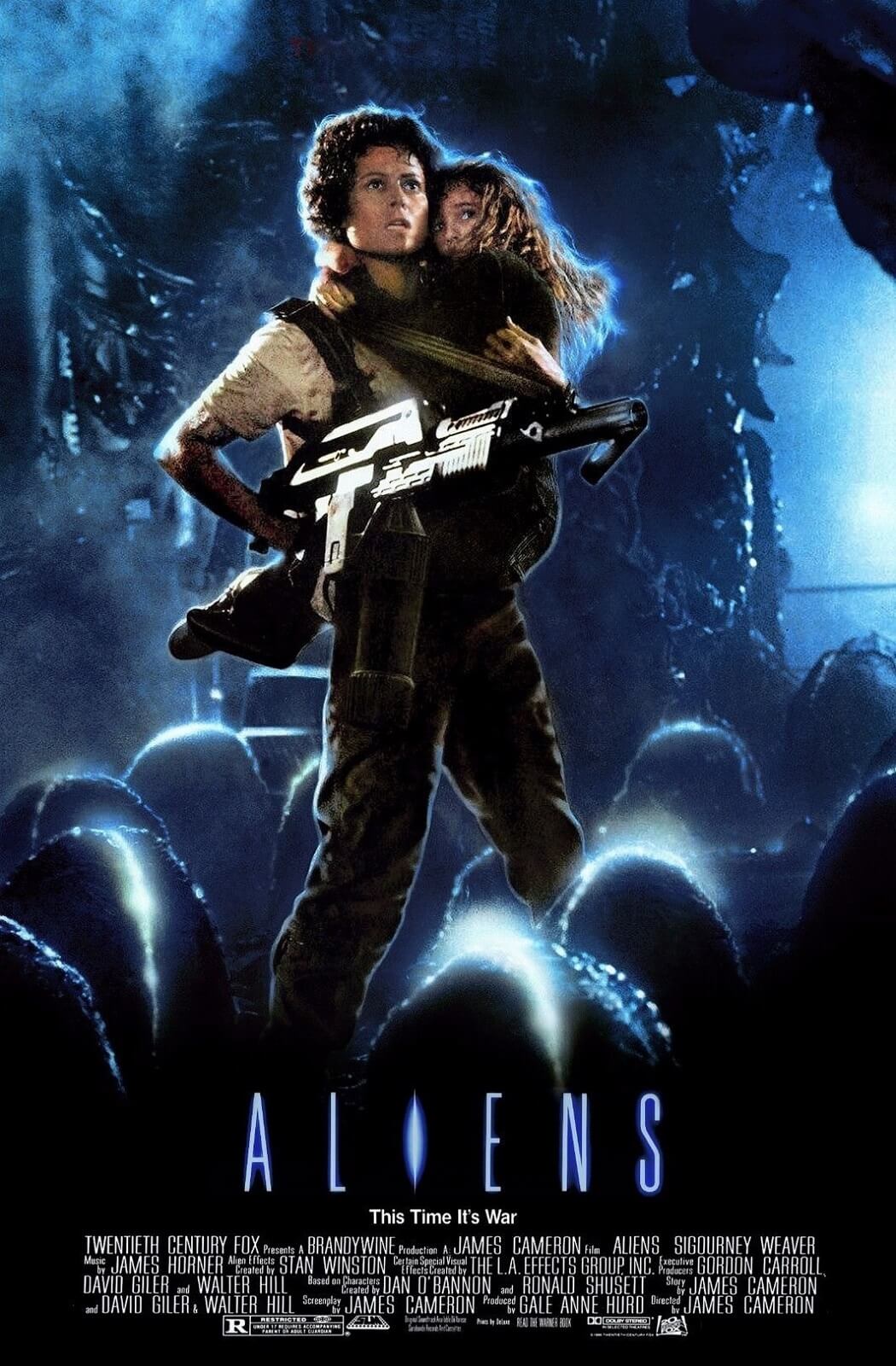

When Alien opened in the summer of 1979, it became an instant commercial hit, earned Fox $78.9 million in domestic receipts, and later won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects. Doing for space what Psycho (1960) had done for showers and Jaws (1975) had done for the ocean, the film was likewise instantly ingrained into pop-culture awareness, only to be copied and used as a model by subsequent science-fiction and horror films. It also catapulted Ridley Scott’s prolific career, which would follow with a series of similarly intelligent yet commercial projects: Thelma & Louise (1991), White Squall (1996), Gladiator (2000), Black Hawk Down (2001), Matchstick Men (2003), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), A Good Year (2006), American Gangster (2007), Body of Lies (2008), and Robin Hood (2010). Only three years after Alien, Scott would once again redefine the sci-fi genre by bringing Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? to the screen with Blade Runner. Fox followed Alien with untold amounts of merchandising and sequels, including James Cameron’s relentless actioner Aliens (1986), David Fincher’s odd but fascinating Alien 3 (1992), and the disgraceful Alien: Resurrection (1997). In the 2000s, Fox opted to combine the Alien legacy with their Predator franchise, resulting in two ham-fisted titles, Alien vs. Predator (2004) and Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem (2007). With each new sequel, the series inched away from the severe level of terror Scott accomplished in his original, until Scott himself returned the franchise to its roots in 2012 with a prequel, Prometheus, followed by Alien: Covenant (2017). Both blended sci-fi spectacle and horror thrills, albeit with underwhelming results

If the sequels and prequels have accomplished anything, apart from nearly removing all credibility from the franchise, they point viewers back to Scott’s original and help us recognize what a masterpiece it is. Accordingly, in 2003, Fox prompted Scott to unveil a “Director’s Cut” featuring previously deleted scenes for a theatrical re-release. Rather than padding the runtime with deleted scenes incorporated back into the film, Scott removed scenes to compensate for those he added and delivered a cut shorter than the original by about a minute. Though one cannot be faulted for preferring the original version—which Scott favors, saying the “Director’s Cut” was a marketing gimmick—the newer cut contains fascinating scenes previously available only as supplements on home video, including a staggering confrontation when Lambert slaps Ripley for refusing to allow the search party back on the ship. The additional footage adds emotion but perhaps takes away from the boiling-over suspense when Ripley finds Dallas cocooned just before she evacuates the Nostromo. A compelling scene nevertheless, one that deepens our understanding of the alien’s process at a pivotal moment.

Much has changed about the science-fiction and horror genres in the thirty years since Alien’s release. A film with this plot today would reveal the alien in half the time (and do so fully, with no end of monster “money shots”), include far more humans for an increased number of screen deaths, and resist the overt sexual overtones present in the film’s visual subtext. Audiences today seem too restless to wait for the kind of absolute answers this film refuses to provide, and contemporary filmmakers seem only too happy to oblige their impatience. But Ridley Scott’s Alien unnerves us by making us wait. And as we writhe about in fear from Giger’s suggestive designs, the film infiltrates its audience deeper than most could ever hope to achieve, doing so with fewer characters and deliberate pacing. Wisely, it recognizes and practices how the Unknown is far more terrifying a notion than full disclosure. Made with uncommonly crafted skill to unsettle the minds and bodies of its audiences, Alien is a profoundly influential work and a lasting classic. The risks taken by this film make it a rarity, while its methods yield a paradigmatic specimen whose combination of genre thrills, bound by great artistry and innovation, have yet to be bested by imitators.

(Edited November 7, 2020)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review